Ada Lovelace and Grace Hopper

ADA LOVELACE

GRACE HOPPER

Chelsea

In 1987, Santa Claus gave me my first computer for Christmas. At that time, women made up more than a third of computer scientists in the United States. Today, it’s close to a quarter. That’s far from parity, especially in a field that women helped invent.

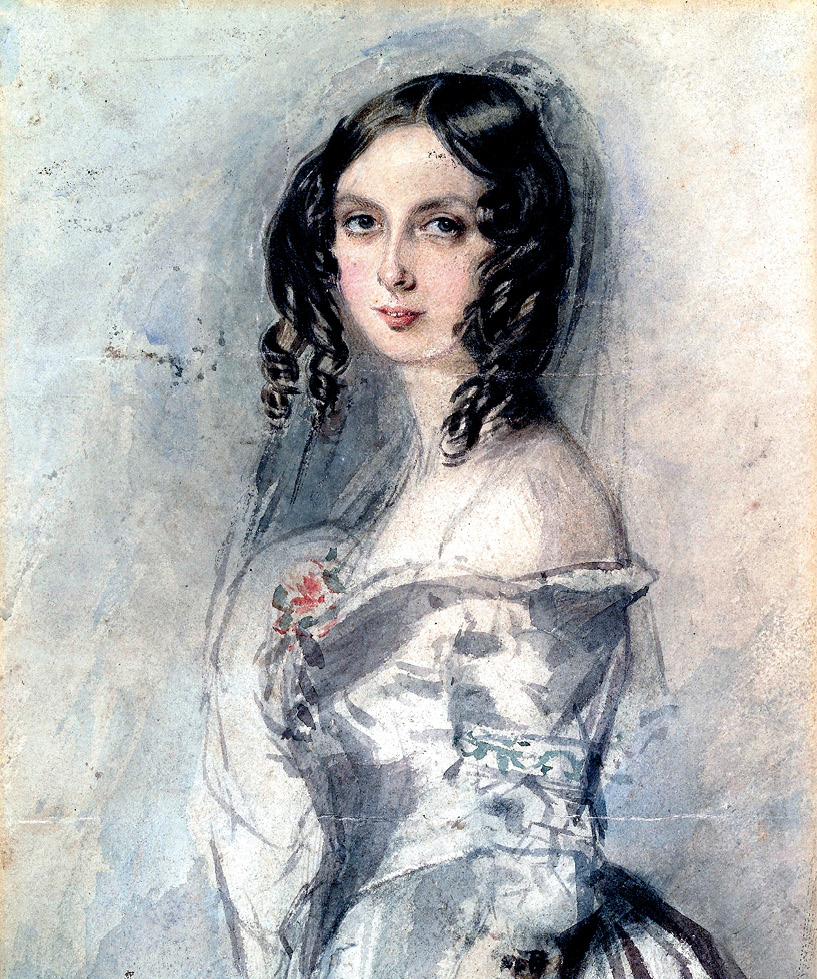

In the nineteenth century, Ada Lovelace did work that still echoes in the computers we use today. Ada’s parents, the poet Lord Byron, and his wife, Annabella, separated when she was a baby; she never saw her father again. Her mother supported her daughter’s interest in math, an unusual pursuit for women in the early 1800s, even those from families as privileged as Ada’s.

Starting as a teenager, Ada worked alongside Charles Babbage, the inventor of an automatic calculator known as the difference machine. She posited that a machine could follow rules, and that numbers could represent other concepts—like music notes or letters of the alphabet. She became the first person—man or woman—to imagine, or at least articulate, that a machine could generate music, not just perform calculations. Ada was also the first to publish an algorithm, or set of steps for solving a mathematical problem, intended for a machine’s use. For these reasons, she is often aptly described as the world’s first computer programmer and the “Prophet of the Computer Age.” It took guts to bring such unheard-of ideas into existence.

“I never am really satisfied that I understand anything; because, understand it well as I may, my comprehension can only be an infinitesimal fraction of all I want to understand about the many connections and relations which occur to me.”

—ADA LOVELACE

Ada died of cancer at thirty-six. Who knows what else she might have imagined or invented had she lived longer. I learned about Ada in college, when I read Tom Stoppard’s play Arcadia (a gift from Marc—then my friend, now my husband). Ada was the inspiration for Thomasina, the play’s most interesting character. I had always loved science—so how did I not know about the woman who helped lay the mathematical groundwork for computers? I should have learned about her in math class, or in my early computer classes. I hope students today learn about the remarkable woman who envisioned a computer’s possibilities long before the first one was invented.

When Grace Hopper was born almost one hundred years after Ada in New York City, mathematics continued to be dominated by men (as math and computer science still are today). Before she turned thirty, Grace had earned a PhD in mathematics, a rare achievement for anyone in 1934. First a professor of math at Vassar College, her alma mater, Grace joined the U.S. Naval Reserve during World War II. She began working with the Mark I computer, becoming only the third person ever to program it. After the war, she continued working with computers in the private sector and in the navy, moving in and out of military service throughout her career.

HILLARY

I thought of Ada, Grace, and the many pioneering women in STEM when, in March 2019, U.S.-based mathematician Karen Keskulla Uhlenbeck became the first woman to receive the prestigious Abel Prize. Among other things, she has explored the mathematics behind the formation of soap bubbles. She described the experience of being one of a small handful of women earning her PhD in math at Brandeis in 1968, writing: “We were told that we couldn’t do math because we were women. I liked doing what I wasn’t supposed to do, it was a sort of legitimate rebellion.” I love that phrase!

Like Ada, Grace imagined that computers could do more than the complicated arithmetic they performed at the time. She used math to help create the first computer compiler, a program that translates words into numerical code, as Ada had once imagined. Her work led to the invention of programming languages. When she began working on proving that computers had more potential than anyone had conceived, she encountered significant cynicism and resistance, particularly from her male colleagues. She didn’t give up in the face of sexism; she pushed forward, tackling new frontiers in math. Grace once said, “If you do something once, people will call it an accident. If you do it twice, they call it a coincidence. But do it a third time and you’ve just proven a natural law!” For her contributions, propelled by her persistence and genius, she’s known today as the Mother of Computing.

I learned about Grace in 1996, when the navy named a new ship the U.S.S. Hopper in her honor, a rare instance of recognizing a woman in such a way. I learned even more about her when I spoke many years later at the Grace Hopper Celebration, the largest gathering of women technologists in the world. It still bothers me that, as with Ada, I never learned about Grace in school, particularly when we started working on computers in high school. We should have known that our work was made possible by Grace’s efforts during and after the war.

Both Ada and Grace deserve to be celebrated every time we sit down at a computer. In recent years, Ada Lovelace Day has become an international holiday dedicated to recognizing the achievements of women in science, technology, engineering, and math. That’s a step in the right direction, but it’s still not enough.