Margaret Knight and Madam C. J. Walker

MARGARET KNIGHT’S INVENTION

MADAM C. J. WALKER

Chelsea

In 1850, when she was twelve years old, Margaret Knight left school in Manchester, New Hampshire, to support her widowed mother by working in a local cotton mill. There, she witnessed a terrible accident. A young boy was impaled by a steel-tipped shuttle carrying thread that had become disconnected from its spool. Child labor was common in the mills of the nineteenth century and the machinery dangerous; it was cheaper to employ children and more expensive to fence the machinery. Fingers, limbs, and lives were lost.

Margaret wanted to prevent more accidents like the one she had seen. A self-taught inventor from a young age, she had grown up building toys for her brothers and tools to make life easier for her mother around the house. This seemed like another problem she could solve. By the time her thirteenth birthday rolled around, she had invented a safety device for textile looms that automatically turned off a machine’s power if it was malfunctioning. Although it would become common at mills throughout the United States, and Margaret’s work helped prevent untold accidents, she received no credit for or income from her invention. Still, she kept inventing.

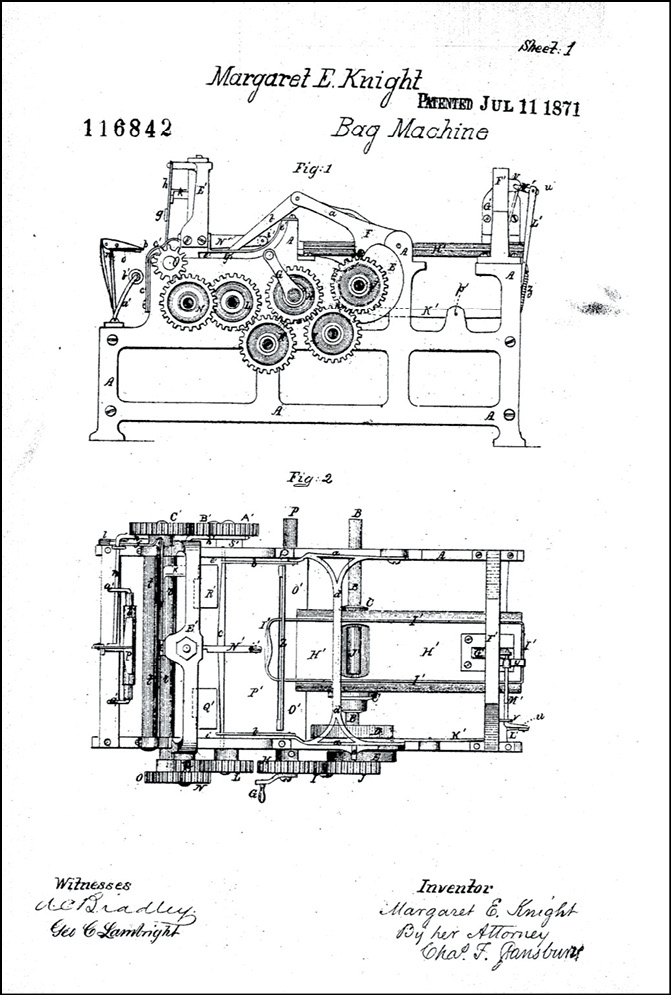

After the Civil War, Margaret went to work at the Columbia Paper Bag Company in Springfield, Massachusetts. Her job was folding every paper bag by hand—an inefficient and time-consuming task. In under a year, Margaret designed a machine that could cut, fold, and glue flat-bottomed bags together. While that might sound simple enough today, at the time, flat-bottomed bags were considered luxury items; most families carried groceries home in paper cones or large envelopes.

When she filed for a patent, her application was rejected. It turned out that a man she had shown her work to in its early phase had stolen her idea, copied it, and successfully applied for a patent, taking credit for her invention. Angry at the injustice of having her idea stolen, Margaret took him to court. When the man who had purloined her idea argued that no woman could possibly be capable of designing a machine like Margaret’s, she presented page after page of hand-drawn blueprints. She won the case. In 1871, Margaret received the patent for her flat-bottomed paper bag–making machine. Although Mary Kies was the first American woman to receive a patent, in 1809 (for a novel approach of weaving straw and silk together), it was still rare for women to be awarded patents. By the end of her career, Margaret had obtained more than twenty. Newer versions of Margaret’s paper bag–making machine are still in use today—so the next time you use a paper bag, or a cloth one modeled after her original design, thank Margaret!

Margaret Knight wasn’t the only woman inventor in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Born in 1867 near Delta, Louisiana, Sarah Breedlove lost both her parents by the time she was seven. As a young, poor black girl in post-Emancipation Louisiana, her only source of education was her church, where she learned to read. Most of her young life was spent working in other people’s homes to support herself, even after she moved in with an older sister in Mississippi. She married her first husband at fourteen and had her only child a few years later. After her husband died, she and her daughter, A’Lelia, moved to St. Louis. When Sarah began to lose her hair in her thirties, she tested lots of different remedies, some of which had been recommended to her by her four brothers, all barbers. She also tried the products of Annie Malone, a black woman hair-care entrepreneur. Sarah wasn’t wholly satisfied with anything she tried that someone else had made or suggested, so she began working on her own formula to fight hair loss. A combination of infrequent hair washing (because of a lack of indoor plumbing and central heating), nutrient-poor diets, and scalp diseases helps explain why hair loss was a fairly common challenge for women, especially black women, in the late nineteenth century. When Sarah’s third husband, Charles Joseph Walker, who had a vibrant career in advertising, encouraged her to start her own hair care line, and to do so under the name Madam C. J. Walker because it sounded catchier, Sarah—now Madam C. J.—began to do just that.

Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower was a line of hair care products and treatments that Madam C. J. developed for herself and then began marketing to other black women, initially in Denver, Colorado, where she worked as a sales distributor for Annie Malone. Annie would later accuse Madam C. J. of stealing her formula; while the ingredients were the same, the formula was slightly different, and Madam C. J.’s marketing effort was wholly her own (with some help from her husband). While she traveled across the country to demonstrate how to use her first signature product and treatment, a scalp conditioning and healing formula, A’Lelia managed the mail-order branch of the business. Sales numbers grew so quickly that she opened her first factory the next year. She moved her business to Pittsburgh and then to Indianapolis to be closer to new markets and railway lines. In 1910, she opened her first factory. She expanded into makeup and other beauty products. She then opened beauty schools to train beauticians on how to use her growing product line. In under a decade, she expanded internationally, eventually building a workforce of forty thousand predominantly black women and men.

Madam C. J. became one of the wealthiest black women of her time and is known as the first self-made black female millionaire (though some historians doubt the veracity of that moniker). “I got my start by giving myself a start,” she would say. She used her resources and considerable platform to support the YMCA and the NAACP, investing in education and speaking out against racism and lynching. She died of kidney failure in New York City in 1919. Eighty-two years later, A’Lelia Bundles published a biography of her great-great-grandmother, On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker.

I was lucky to learn about Margaret Knight and Madam C. J. Walker thanks to my American history teacher in my junior year of high school, Mr. Ellis Turner. He staunchly believed American history was too often populated by just men, and particularly white men, and he worked hard to introduce us to American women inventors, reformers, artists, advocates, authors, journalists, and leaders who helped push our country forward. If they were alive today, I would hope Margaret Knight and Madam C. J. Walker would be heralded and recognized by all as the innovators they clearly were.