Elizabeth Blackwell, Rebecca Lee Crumpler, and Mary Edwards Walker

ELIZABETH BLACKWELL

REBECCA LEE CRUMPLER

MARY EDWARDS WALKER

Chelsea

Elizabeth Blackwell was an unlikely candidate to become the first woman in America to receive a medical degree. She wrote in her autobiography, Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women, that as a young woman, she initially “hated everything connected with the body.” But she found herself called to medicine by a dying friend who Elizabeth believed suffered unnecessarily because she didn’t have access to a well-qualified woman physician. Elizabeth understood before most that the life experiences of doctors matter to the quality of care that patients receive, particularly when prejudice and bigotry abound.

In the 1840s, a decision to become a doctor didn’t mean Elizabeth could immediately start studying medicine. Although she had been tutored alongside her brothers and been a teacher, she was still a woman. She moved to Philadelphia in 1847, hoping friends there could help her apply to medical school. All but one school rejected her: Geneva Medical College in rural New York. Though it turned out her admission had been intended as a “joke” by the school, Elizabeth took them seriously and enrolled.

In 1849, she received her medical degree, having earned the grudging respect of her professors and classmates. She traveled abroad to gain more experience, working in London and Paris, where she contracted an infection that cost her the vision in one eye. Although she knew it would prohibit her from becoming a surgeon, as she had once dreamed, she refused to give up her medical career. She opened a small women’s health clinic in New York that grew into the New York Infirmary for Women and Children.

In time, she became more and more convinced that women doctors were an important part of ensuring that women patients received good care. In the late 1860s, she opened one of the first medical colleges for women in the United States, with a focus on training new doctors to care for poor women and children. A few years later, she helped establish the first medical school in Britain to train women as physicians.

I first learned about Elizabeth from Sara Auld, my senior-year roommate at Stanford. Sara’s thesis focused on Charlotte Blake Brown, one of the first woman doctors in California. Like Elizabeth, Charlotte left home to study medicine and then opened a hospital focused on women and children in San Francisco. Listening to Sara talk about her research into this remarkable nineteenth-century American is one of my favorite memories from college.

Sara’s interest in Charlotte and Elizabeth prompted us to look for other women medical pioneers and heroes, leading us to Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler, the first black woman doctor in the United States. Born in Delaware in 1831, she grew up in Pennsylvania watching her aunt care for sick people in their community. Rebecca worked as a nurse until she was accepted to medical school. After she graduated in 1864 from the New England Female Medical College, she started her career as a physician caring for low-income women and children in Boston. When the Civil War ended, she moved to Virginia, where she worked for the Freedman’s Bureau to care for freed slaves.

Rebecca faced intense racism and sexism from her colleagues in the South. Her fellow physicians snubbed her, and pharmacists ignored her. She couldn’t fully take care of her patients if prescriptions went unfilled. She moved back to Boston and continued her career while also working on a book about good medical care for mothers and children. When, in 1883, she published A Book of Medical Discourses: In Two Parts, Rebecca may have been the first black American to have a medical textbook in print. It was notable for its focus on children at a time when most medical tracts focused solely on adults. Her book is dedicated to “mothers, nurses, and all who may desire to mitigate the afflictions of the human race.” Her legacy lives on in the Rebecca Lee Society, one of the first medical societies for black women.

Through our explorations, Sara and I also found Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, the only woman in her medical school class at Syracuse Medical College in 1855. She was a practicing physician when the Civil War broke out. She desperately wanted to enlist in the Union Army as a surgeon but wasn’t allowed to because she was a woman. Initially, she was called a nurse, since women generally weren’t considered doctors. Because women were not allowed to enlist, Mary had to volunteer, working for free at a temporary hospital, first in Washington and then in Virginia, where she traveled to Union field hospitals across the commonwealth. Mary watched other surgeons routinely perform dangerous, unnecessary amputations on soldiers suffering from fractures and other injuries. She began discreetly advising soldiers against the procedures when she thought they were not warranted. After the war, she would receive thank you letters from patients whose limbs had healed. When her medical credentials were finally accepted, she moved to Tennessee and became a War Department surgeon—a paid position that was the equivalent of a lieutenant in status.

“Let the generations know that women in uniform also guaranteed their freedom.”

—DR. MARY EDWARDS WALKER

During the war, she crossed enemy lines to treat the wounded and was arrested by Confederate forces as a spy. She was held for several months before she and some of her colleagues were exchanged “man for man” for Confederate medical officers. After her release, she was contracted as a surgeon—the first female surgeon ever commissioned in the army—and served through the end of the war.

Mary was not only a surgeon; she was also an activist. One of the causes close to her heart was for women to be able to wear clothes that actually allowed them to move freely. Born in 1832, in Oswego, New York, Mary worked on her family’s farm from a young age, wearing boys’ clothing, which was much better suited to physical labor than the tight corsets and full skirts that women were expected to wear. Years later, when she married one of her medical school classmates, she wore trousers and a dress coat. (She also struck “to obey” from the marriage vows, and she kept her own name.) Throughout the Civil War, she famously sported “bloomers,” or a combination of a dress and pants. During her time in Virginia, though she was not yet officially credentialed by the military, she designed her own uniform: blue with a green sash, similar to the clothing worn by male physicians on the battlefield. The New York Tribune described her in an article: “Dressed in male habiliments… she carries herself amid the camp with a jaunty air of dignity well calculated to receive the sincere respect of the soldiers.… She can amputate a limb with the skill of an old surgeon, and administer medicine equally as well. Strange to say that, although she has frequently applied for a permanent position in the medical corps, she has never been formally assigned to any particular duty.”

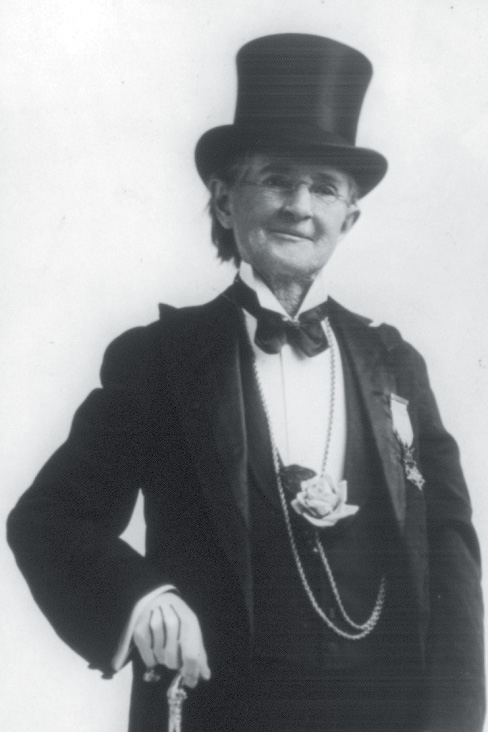

After the war Mary traveled the country, lecturing on dress reform, and was even elected president of the National Dress Reform Association. She sported men’s pants, a top hat, and a bow tie and was arrested several times for “impersonating” a man. (Keith Negley’s wonderfully titled children’s book, Mary Wears What She Wants, tells her story and is a favorite in our house!) She used her public platform to campaign for equal rights for women for the rest of her life, including advocating for a woman’s right to vote. In 1865, Mary was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, the first woman to be so recognized. As hard as it is to believe, she is still the only woman ever to be deemed worthy of this honor. In 1917, Congress rescinded her medal—along with hundreds of others—citing a lack of combat experience. Dr. Walker refused to return the medal. Instead, she wore it every day until her death. Decades later, President Jimmy Carter posthumously reinstated the award.

These are just a few of the many women who felt called to be physicians before most medical schools admitted women. They are part of a global sisterhood of women whose impact continues to this day—women like Kadambini Ganguly, who in 1886 became the first Indian-educated woman doctor; and Yoshioka Yayoi, who in 1892 became the first woman physician in Japan and later founded the Tokyo Women’s Medical School. All of them fought not just to break down barriers for themselves but to advocate for their peers and the women who would come after them.