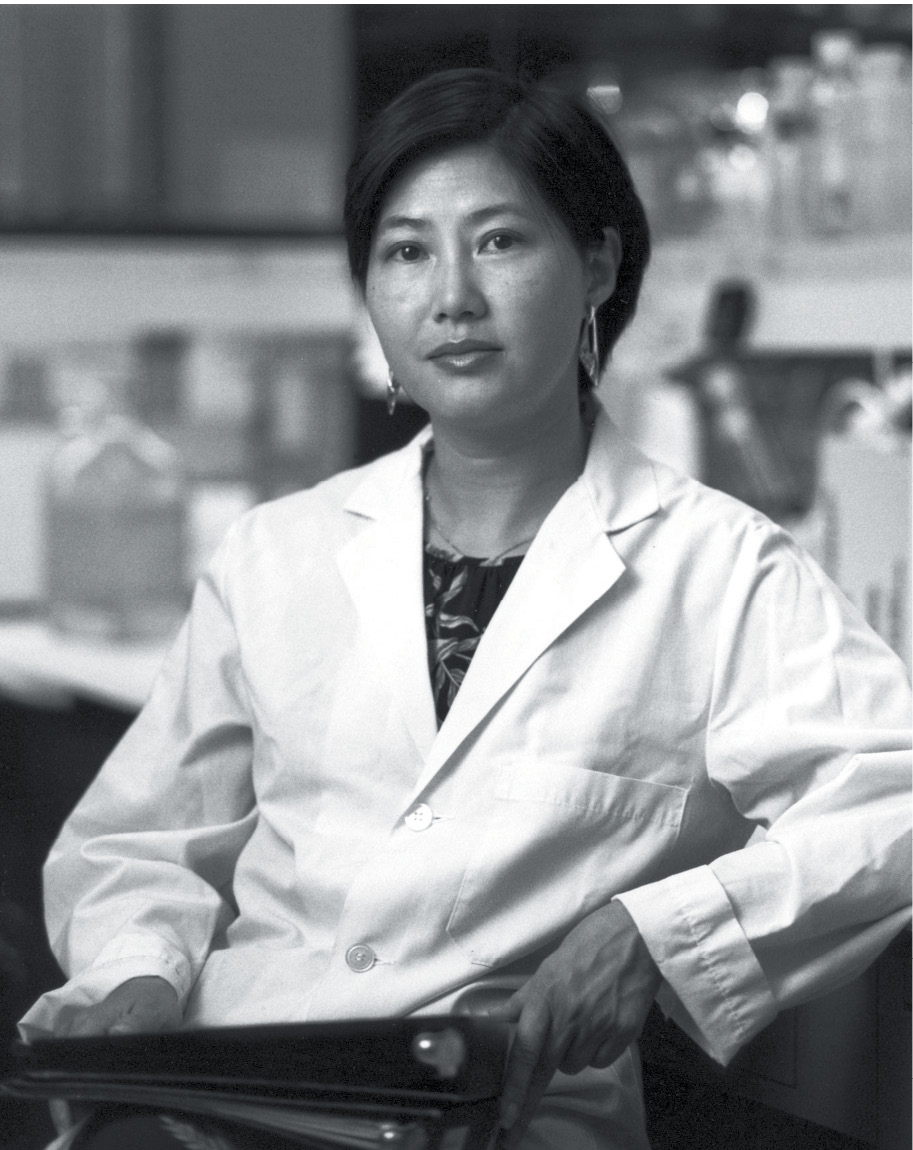

Flossie Wong-Staal

Chelsea

While Yee Ching Wong was growing up in the 1950s in Guangzhou, China, and later in Hong Kong, none of the women in her family worked outside the home. Still, her parents and her teachers encouraged her interest in learning, especially when it came to the sciences. She excelled in school and decided to go to college in the United States. In preparation, her teachers urged her to change her name to fit in with her new classmates. She became known as Flossie, after a typhoon that had struck the area a week before. When I first learned that detail, it struck me as an extraordinary metaphor, given that Flossie would help us understand the greatest and most threatening public health “storm” in my lifetime.

Her academic journey in science started at age eighteen, when Flossie moved to California to study bacteriology at UCLA. Her natural talent combined with hard work led to her earning a BS in just three years. In 1972, before she had turned twenty-five, she earned a PhD in molecular biology.

Flossie’s postdoctoral work took her to the National Cancer Institute, where she began a lifelong study of retroviruses, a group of viruses that insert their viral DNA into the DNA of a host cell. In 1983, she was a core part of the team that identified a retrovirus known as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) as the cause of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). A French team at the Pasteur Institute had simultaneously identified the virus, and both teams published their findings in Science a year apart. After years of disputing who had made the discovery first, the lead scientists agreed to share the credit and work together to fight a scourge that was already infecting tens of thousands around the world and tens of millions today. Now it’s generally agreed that the French team first isolated the HIV virus, and Flossie’s team first recognized it as the cause of AIDS. What is not disputed is that in 1985, Flossie became the first person in the world to clone HIV. That breakthrough enabled Flossie and her team to map the virus, paving the way for the development of blood tests to detect the presence of HIV.

“It adds to the joy of discovery to know that your work may make a difference in people’s lives.”

—FLOSSIE WONG-STAAL

After almost two decades at the National Cancer Institute, in 1990, Flossie continued her research on HIV/AIDS at the University of California at San Diego. She focused on the then emerging field of gene therapy, moving genes or parts of genes into cells that have missing or defective genes in order to help treat or prevent diseases. Flossie explored the use of gene therapy to repress HIV in stem cells. In particular, she focused on trying to better understand the relationship between a type of protein and the Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions found on some patients with HIV/AIDS. Her work was about more than science for science’s sake; it led to better treatments.

Not content to make one major discovery, Flossie eventually moved on to another challenge. Later in her career, she began applying her work in HIV/AIDS to hepatitis C, a virus that also spreads through transfusions, dirty needles, and sex (though sexual transmission is rare, unlike with HIV/AIDS). Left untreated, hepatitis C can cause liver damage, liver cancer, and liver failure, all of which can lead to death. Flossie founded a company focused solely on discovering and developing drugs to treat this deadly disease. More than seventy million people worldwide are believed to be infected with hepatitis C, and hundreds of thousands of people each year die because they don’t receive early diagnosis or the treatment that exists. More troubling still, hepatitis C rates are currently on the rise in the United States. Now in her seventies, Flossie is still hard at work confronting the virus. I hope she will have the same impact on hepatitis that she had on HIV/AIDS. She is remarkable not only for her talent but for her tenacity and unwillingness to let any virus go unchallenged.