Nza-Ari Khepra, Emma González, Naomi Wadler, Edna Chavez, Jazmine Wildcat, and Julia Spoor

NZA-ARI KHEPRA

EMMA GONZÁLEZ

NAOMI WADLER

EDNA CHAVEZ

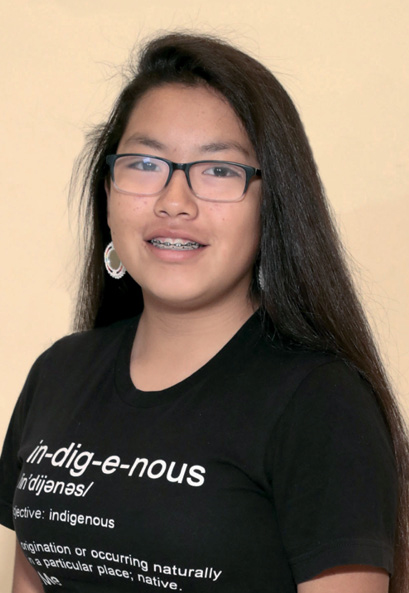

JAZMINE WILDCAT

JULIA SPOOR

Chelsea

According to the Giffords Law Center—named in honor of Gabby Giffords—three million children are exposed to gun violence each year. More than 215,000 students in America have experienced a shooting at their school since the tragedy at Columbine High School in 1999. Sixty percent of teenagers in America say they’re worried about one happening at their school. And two-thirds of gun deaths are deaths by suicide: Gun suicides claim the lives of nearly 22,000 Americans every year, including more than 950 children and teens. In fact, guns are now the second leading cause of death for kids and teens in America, after car accidents.

HILLARY

It’s chilling to see children as young as elementary schoolers marching with signs that read “Am I Next?” And it broke my heart when a high school student who had just survived a shooting in Santa Fe, Texas, told a reporter she wasn’t surprised because “it’s been happening everywhere” and she “always kind of felt like eventually it was going to happen here, too.” We are failing young people every single day that we do not act.

All of these statistics are tragic; none is inevitable. We know that commonsense gun safety laws lead to fewer gun deaths, including fewer suicides and fewer mass shootings. That’s the future that a new generation of activists is working toward, spurred on by their own experiences with gun violence.

Nza-Ari Khepra was sixteen years old when her friend Hadiya Pendleton was killed on a playground near their high school in Chicago. A week before she was killed, Hadiya had performed as a majorette with her school band at President Obama’s second inauguration. “Hadiya was like a magnet to everyone she met,” Nza-Ari told the website The Trace. “Once she knew you, she made sure to go out of her way to make you feel special.”

A month after the shooting, Nza-Ari and her friends started an organization, Project Orange Tree, dedicated to educating young people about violence and confronting its root causes. “One of our small goals at the beginning stages of Project Orange Tree was to host food drives because neighborhoods affected by the city’s gun violence were also food deserts,” she said. “That may seem like an unimportant thing to do when you’re fighting against gun violence, but it was one small thing that we could accomplish.”

Today Nza-Ari is a twenty-two-year-old graduate of Columbia University. She returned to Chicago for her job, and to continue her activism with Project Orange Tree to prevent more tragedies in her city and our country. When I met her at the Clinton Global Initiative University meeting in 2018, she talked about how racism, poverty, and gun violence intersect. Her courage and candor in tackling such enormous and important issues makes her a role model to younger students—and those of us who aren’t as young. “Maybe you care more about domestic violence than you do urban violence, or gun suicides, or accidental shootings,” she tells anyone who will listen. “Do whatever you’re most passionate about.”

“Gun violence is such a complex issue. We need to recognize every portion of it—mass shootings, inner-city violence, domestic violence. It hurts that such dreadful situations ignite people into action, but at the same time, that’s exactly how I got started.”

—NZA-ARI KHEPRA

Days after the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, that killed seventeen of her classmates, Emma González stood behind a podium at a rally. “Every single person up here today, all these people should be home grieving,” she started. “But instead we are up here standing together, because if all our government and president can do is send thoughts and prayers, then it’s time for victims to be the change that we need to see.” She kept going, wiping tears from her face. By the time she finished her speech, she had given millions of people a new sense that maybe this time would be different, that gun laws might change. “They say no laws could have prevented the hundreds of senseless tragedies that have occurred,” she said. “We call BS. That us kids don’t know what we’re talking about, that we’re too young to understand how the government works. We call BS.” She was absolutely right.

Emma spent her whole life in Parkland, raised by her mother, a math tutor, and her father, an attorney who came to the U.S. from Cuba. She built her skills as an activist while serving as president of her school’s Gay-Straight Alliance. In the days after the shooting, she, along with her fellow Parkland students and students across the country who had been speaking out about gun violence for years, started organizing. The Parkland students set up a makeshift headquarters in one of their living rooms, met with young activists in other cities, and got to work putting together the March for Our Lives. I took my then three-year-old daughter, Charlotte, to the march in New York City. I wanted her to see young people leading the efforts to save other young people from gun violence—a fight that never should have come to them, just like bullets never should have taken those students’ lives in Parkland or in any school, mall, park, movie theater, sidewalk, or anywhere in our country.

During the March for Our Lives rally in Washington, D.C., six weeks after the shooting in Parkland, Emma listed the names of students who were killed, then stood on the stage in silence until she had been there for six minutes and twenty seconds, the amount of time the shooting lasted. Emma is remarkable for her skills as an organizer, her gifts as an orator, and her ability to channel her sadness, her grief, and her passion into action. After the shooting in Parkland, she and her fellow students organized the largest single day of protest against gun violence in history. Inspired by the Freedom Riders of the 1960s, they spent the summer touring the country talking about gun violence prevention; along the way, they registered more than fifty thousand new voters. All of this helped fuel a historic youth turnout in the 2018 midterm elections, which saw a record number of thirty-three NRA-backed candidates lose their seats in Congress.

“We are grieving, we are furious, and we are using our words fiercely and desperately because that’s the only thing standing between us and this happening again.”

—EMMA GONZáLEZ

Another student who captured attention at the March for Our Lives was eleven-year-old Naomi Wadler from Alexandria, Virginia. After the Parkland shooting, her mother, Julie, talked to her about what had happened and explained that one of her own friends from high school, Fred Guttenberg, had lost his fourteen-year-old daughter Jaime that day. When Naomi learned that high school students across the country were planning to walk out of class on March 14, the one-month anniversary of the shooting, she organized a walkout of her own at her elementary school.

When she took the stage at the March for Our Lives rally in Washington, Naomi was confident, poised, and determined. And when she spoke, she brought a critical perspective, and one too often ignored in national conversations about gun violence. “I am here to acknowledge and represent the African American girls whose stories don’t make the front page of every national newspaper, whose stories don’t lead on the evening news,” she said. “I represent the African American women who are victims of gun violence, who are simply statistics instead of vibrant, beautiful girls full of potential.” I admired her bravery as one of the youngest speakers that day. She raised her voice and said something that so urgently needed to be heard.

Seventeen-year-old Edna Chavez was already politically engaged before the March for Our Lives. As a student in South Los Angeles, she’d knocked on her neighbors’ doors before the 2016 election and asked to talk with them about issues, including immigration reform. When her father was incarcerated for being an undocumented immigrant, and later deported, it inspired her to pass out flyers in her community with information about immigrants’ legal rights, and to hold “Know Your Rights” workshops to help people safely manage interactions with law enforcement.

“My friends and I might still be eleven, and we might still be in elementary school, but we know. We know life isn’t equal for everyone and we know what is right and wrong.… We know that we have seven short years until we, too, have the right to vote.”

—NAOMI WADLER

“This is normal, normal to the point that I learned to duck from bullets before I learned how to read.”

—EDNA CHAVEZ

Edna spoke at the March for Our Lives as a sister whose brother, Ricardo, had been killed in a shooting outside their home. “That moment onstage, it was not just me,” she told Teen Vogue later. “It was people from Chicago, from Baltimore, from so many different areas that we were talking about everyday gun violence. We made sure it was engraved into people’s minds that shootings happen every day in low-income communities.” As she ended her speech at the march, she said: “Remember my name. Remember these faces. Remember us and how we’re making a change. La lucha sigue.” The fight continues.

Jazmine Wildcat’s family owns guns, like a lot of people in Riverton, Wyoming, where she lives. But Jazmine, who is a member of the Northern Arapaho Tribe, isn’t afraid to confront deep-seated cultural ideas, even if she’s doing it alone. When Jazmine, then a fourteen-year-old student, organized a walkout at her school in 2018, “We only had about fifty people out of about three hundred take part,” she said. “People came and mocked us.”

For Jazmine, this fight is personal. She remembers having to help her family members collect her grandfather’s guns after he had threatened to take his own life. Her grandfather had PTSD from the Vietnam War; she believes that he never should have had access to a gun in the first place.

Being from a conservative town, Jazmine is used to dealing with people who don’t agree with her. She has also had a lot of practice dealing with online trolls. They have called her ignorant, weak, and worthless because of her activism. But Jazmine remains steadfast. She continues to write letters to lawmakers, calling on them to pass sensible gun laws. When she grows up, she says, she might become a politician, fighting for the same issues that are on her mind right now. I hope she does.

“I have my work cut out for me.… We cannot just sit here and wait for the next violent event to happen.”

—JAZMINE WILDCAT

“I feel passionate about a lot of things and I feel angry about a lot of things and the ability that I have to change it is not something I ever want to overlook.”

—JULIA SPOOR

September 25, 2009, is a day Julia Spoor will never forget. Ten days before her eighth birthday, her father died by suicide. Her father, Scott, was a forty-three-year-old engineer and had struggled with depression; he had previously attempted to take his own life a year earlier. A few years after his death, Julia finally learned how her dad had died. “With other methods of suicide there’s still a chance,” she pointed out later. “There is more time between the act and death for the possibility of a reversal. But not with a gun.”

Julia wanted to use her loss to help other families protect loved ones struggling with depression and other mental health issues, and to stand up to gun violence broadly. When she was thirteen, she started marching with her mother and volunteering with Moms Demand Action. Two days after the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas, she cofounded Students Demand Action, a national group led by high school and college students. They are currently forty thousand strong and growing.

These young leaders and so many others who are working on the issue of gun violence prevention come from different places of experience and pain. They are unified by their courage to stand up to anyone who values a gun more than their lives or the lives of their friends. They are fiercely imagining a different future. I look forward to the day when the movement they’re building out of their anger, grief, and sadness succeeds, and future generations no longer have to be angry, go to school in fear, or mourn the loss of family and friends to gun violence.