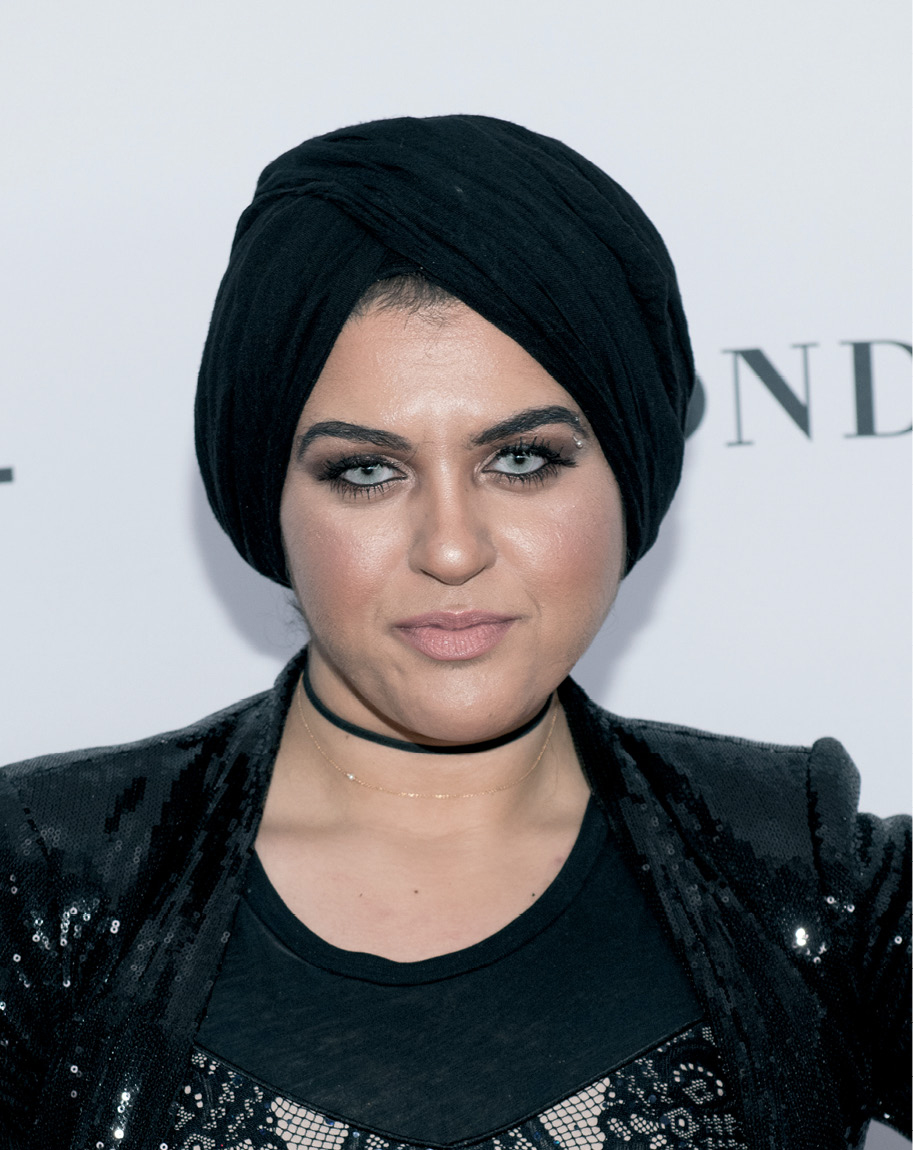

Amani Al-Khatahtbeh

Chelsea

Amani Al-Khatahtbeh was nine years old and living in New Jersey on September 11, 2001. Her parents had moved to the United States from Jordan and Palestine because they wanted to surround Amani and her brothers with opportunities to go as far as their dreams could take them. But after 9/11, Amani found herself scorched by racism and rampant Islamophobia, including in her own school and community.

At seventeen years old, she started an online magazine called MuslimGirl. “It was my personal refusal from having Muslim women’s voices be exploitatively collected, hijacked, and sidelined by media corporations that claim and twist our narrative,” she later wrote. “It began as a way for millennial Muslim girls to connect and communicate with each other, and evolved into a platform to defiantly carve out a space for ourselves in the middle of post-9/11 anti-Islam hatred, stereotypes, and misconceptions.” When she started MuslimGirl in 2009, nothing like it existed in the United States. She knew it was important for her and for other young Muslim American women, and she wanted to help amplify voices like hers. Each time she checked, the site had more views.

“People always ask me, ‘How did you start MuslimGirl?’… I bought a domain, got some hosting, and ‘started.’ But that was the easy part. The questions people should be asking me are, ‘How did you stick with MuslimGirl throughout college when all you wanted to do was go to concerts and chill with friends in the dorms?’ ‘What did you respond to your father when he suggested that maybe you should “start considering something serious” after you graduated?’… that’s where it gets a whole lot more difficult.”

—AMANI AL-KHATAHTBEH

Amani kept MuslimGirl going beyond high school. She worked on the site while a student at Rutgers, all while serving as the opinions editor of the student newspaper—the first Arab Muslim American to hold the position. After college, she worked for a nonprofit in D.C. She left when she landed her dream job working in media in New York City—but the company collapsed before she started. She moved to New York anyway and turned her focus to building MuslimGirl as a full-time job. The site saw a 90 percent increase in traffic that year alone. By 2017, it had 1.7 million page views a year.

Today MuslimGirl has a team of more than forty people and produces content “at the intersection of Islam and feminism,” which Amani sees as complementary; she’s trying to help others see it that way, too. The platform Amani built took on new relevance during and after the 2016 election, when Islamophobia spiked once again, this time stoked by (first candidate then) President Trump. She and her staff published a “Crisis Safety Manual for Muslim Women,” and she spoke out against Donald Trump’s attacks on Muslims. “His comments perpetuate the Islamophobic attitudes that compelled us to advise Muslim women at the time to carry their phones charged at all times, know which numbers to call or apps to use to record a hate crime, and consider less conspicuous hijab styles in areas of extreme threat,” she said.

Even in this hostile environment, Amani has preserved MuslimGirl as a place that celebrates her community. Recent headlines range from “Stop What You’re Doing and Bake These Bars for Your Next Iftar Party” to “How a Quote from the Qur’an Affected My PTSD” to “So What Does an Abnormal Period Actually Mean for Your Fast?” On March 27, 2017, she launched Muslim Women’s Day, which has been celebrated every year since by elected officials, activists, artists, and more.

In 2016, I met Amani at the Clinton Global Initiative University. She took part in a discussion on having “The Courage to Create,” which explored what it takes to move from having a great idea to making that idea a reality. As Amani spoke, her courage was evident—as was her passion to share why she believed anyone could create something meaningful, disruptive, and powerful, as she had with MuslimGirl.

That courage was again palpable when I read the autobiography she published later that year, Muslim Girl: Coming of Age. It chronicles her upbringing and her personal struggles with feelings of not being enough—struggles that were amplified by formative years spent experiencing acute Islamophobia and racism.

In May 2017, Amani and I were on a panel together in Washington, D.C., at the Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere (CARE) national conference. The conference’s theme was “Now More Than Ever,” and we spoke about the many challenges that girls and women face today. We discussed how those of us with a platform have the obligation to share it, to give a voice to the historically voiceless. I was impressed by Amani’s continued willingness to take on difficult subjects, knowing that sometimes her job is to force everyone, including her own readers, to question their own views. “We published a conversation from a transgender Muslim woman convert about what her experience has been,” she said in an interview. “She referred to God as ‘She’ in her article and everyone just went haywire.”

As Amani’s work has reached bigger and bigger audiences, and more and more people have wanted to feature her, she has stayed true to the values that led her to start MuslimGirl in the first place. In her writing and on social media, she tackles the new challenges that come with being recognized, including tokenization. “There have been a lot of times where different outlets have wanted to use me as an ornament, to tick off that box where a Muslim woman is included without having to speak, and that’s important for me to consider,” she has said. She openly addresses the privilege that comes with being beautiful, Western-educated, and lighter-skinned. She lives her values, even when it means passing up a chance to be publicly celebrated: When Revlon wanted to give her an award for her advocacy in 2018, she turned it down because she objected to the views of another nominee.

Amani has never been the kind of person to wait for public opinion to shift or our political climate to get better. Instead, from the time she was a teenager, she has taken it upon herself to carve out a space where she can create the world she envisions—the world that Muslim girls, and all girls, deserve.