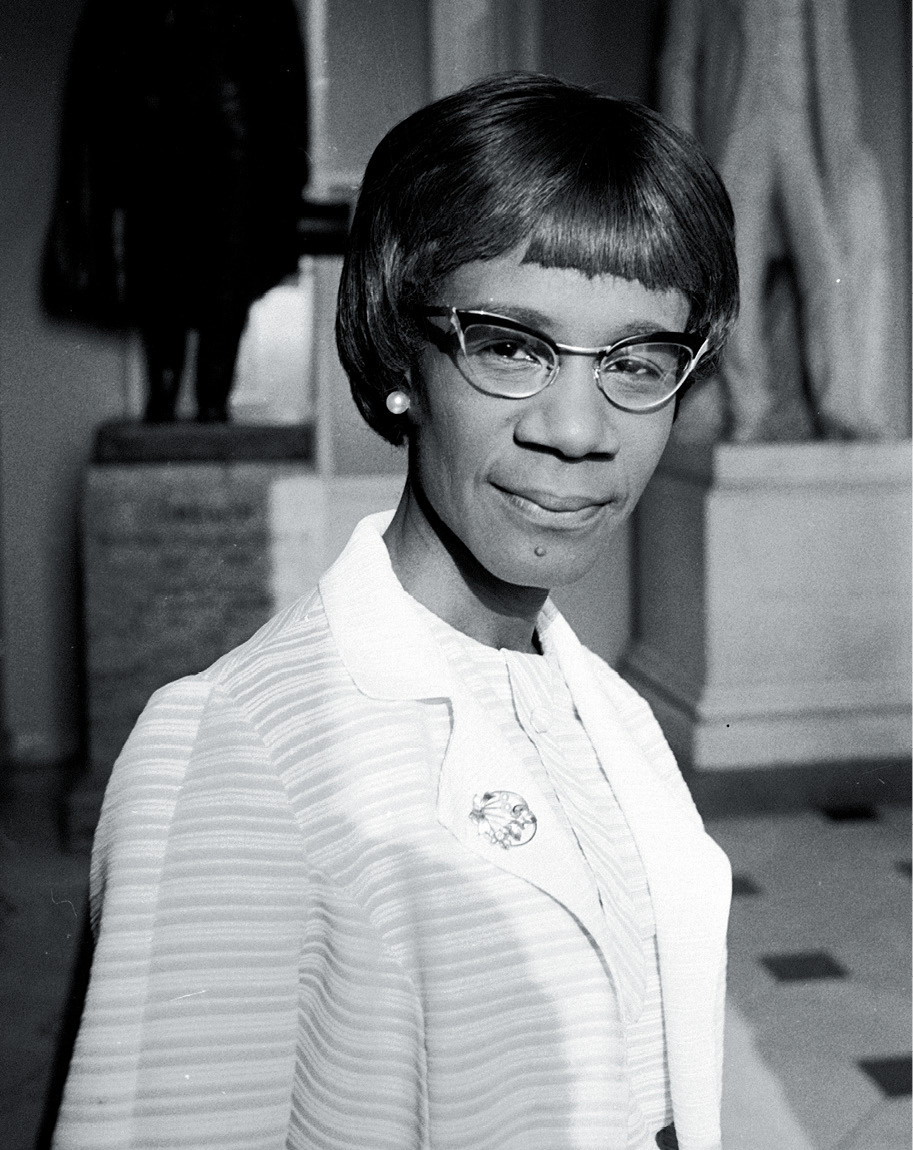

Shirley Chisholm

Hillary

Long before I ever dreamed of running for office myself, there was Shirley Chisholm. She was a woman of tenacity, ingenuity, and pride. When she became the first woman to run for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination in 1972, her campaign slogan defiantly proclaimed: “Unbought and Unbossed.” Born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1924, she stood tall at a time when women, and black women in particular, faced more shut doors than open ones in nearly every corner of American life.

I was in college when I first heard about Shirley, and I avidly followed her career. The daughter of immigrants, she started out in the 1950s as a nursery school teacher and rose in the ranks to become the director of two day care centers. Because of her expertise in education, she would go on to consult with the city of New York on day care programs. In 1968, when redistricting efforts added a new congressional district in her neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn, Shirley decided to throw her hat in the ring. She campaigned on her deep roots in the community. During her campaign, she would drive through the district in a sound truck, announcing: “Ladies and gentlemen, this is fighting Shirley Chisholm coming through.” She beat three candidates in the primary. In the general election, she faced an opponent who argued that the district needed “a man’s voice in Washington,” not a “little schoolteacher.”

CHELSEA

If anything, we need more teachers and early childhood education specialists in Washington. That was true then and it’s true today.

During her campaign, Shirley went door-to-door, meeting families in housing projects and speaking to people in fluent Spanish. She won the general election and became the first black woman ever elected to Congress.

Some suggested that breaking that barrier was enough—that once she was in Congress she should stay quiet, keep her head down, and not make waves. Shirley wasn’t interested in that at all. Above all else, she was a legislator who got things done—an attribute that inspired me then and still does. If it meant saying the unpopular thing, well then, she’d say the unpopular thing. People called her brusque, pushy, impolitic—the kind of things people have always said about strong women. None of it stopped Shirley. “I have no intention of just sitting quietly and observing,” she said. And she didn’t.

From her first days in office, she fought for the rights of workers and immigrants, poor children and pregnant women. In 1971, she worked on legislation along with Congresswoman Bella Abzug of New York and Senator Walter Mondale of Minnesota to provide federal funds for child care for the first time. Though the bill was vetoed by President Richard Nixon, it sent a resounding message. The next year, she was instrumental in creating the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) to make sure “poor babies have milk and poor children have food.” The Children’s Defense Fund, where I worked during law school, supported both bills and considered Shirley a champion for children. I did, too.

She fought successfully to extend unemployment insurance and minimum-wage protections for domestic workers because, growing up in Brooklyn, she saw how “domestics” worked themselves to the bone and were often exploited or left destitute if their job disappeared. She was a champion for Title IX because she knew from her own life how hard women had to fight for their education—and because, as a teacher, she believed education was the key to just about everything.

“At present, our country needs women’s idealism and determination, perhaps more in politics than anywhere else.”

—SHIRLEY CHISHOLM

Shirley didn’t just leave her mark on America; she left her mark on Congress. She cofounded the Congressional Black Caucus and the Congressional Women’s Caucus, because she knew firsthand how hard it was to be both a black person and a woman in Congress. She wanted to make sure everyone who came up after her wouldn’t have to struggle quite as hard as she did. She saw that as a sacred responsibility. And as one of those people who did come up after her, I will always be grateful for that.

CHELSEA

The first elected women I ever remember my mom telling me about as a very young girl were Shirley Chisholm and Geraldine Ferraro. She wanted to be absolutely sure I grew up knowing women could be and do anything, and so could I.

Shirley’s run for president in 1972 was surprisingly effective given her meager fund-raising, the logistical difficulties of waging a national campaign, and the resistance she faced as a black American and a woman. She received 152 first-ballot votes at the Miami Beach Convention, coming in fourth behind George McGovern, the eventual nominee. Years later, Shirley said she ran for president “In spite of hopeless odds… to demonstrate the sheer will and refusal to accept the status quo.” She was also very clear about the obstacles she faced as a woman in politics. “When I ran for president, I met more discrimination as a woman than for being black. Men are men.”

I thought about Shirley often when I was out on the campaign trail. It’s not easy running for president. But even my hardest days were nothing compared to hers. She ran in the face of unimaginable discouragement and hostility. But she kept going. It was as if all that hostility only fueled her fire. “If you can’t support me and you can’t endorse me, get out of my way,” she’d say. A lot of people did end up supporting her. They knew no one would work harder.

At the end of her life, Shirley knew that she had made history. But she didn’t want to be celebrated just for the barriers she crossed. That felt secondary to her. “I don’t want to be remembered as the first black woman who went to Congress. And I don’t even want to be remembered as the first woman who happened to be black to make the bid for the presidency. I want to be remembered as a woman who fought for change in the twentieth century. That’s what I want.”

Well, Madam Chisholm—you got it.