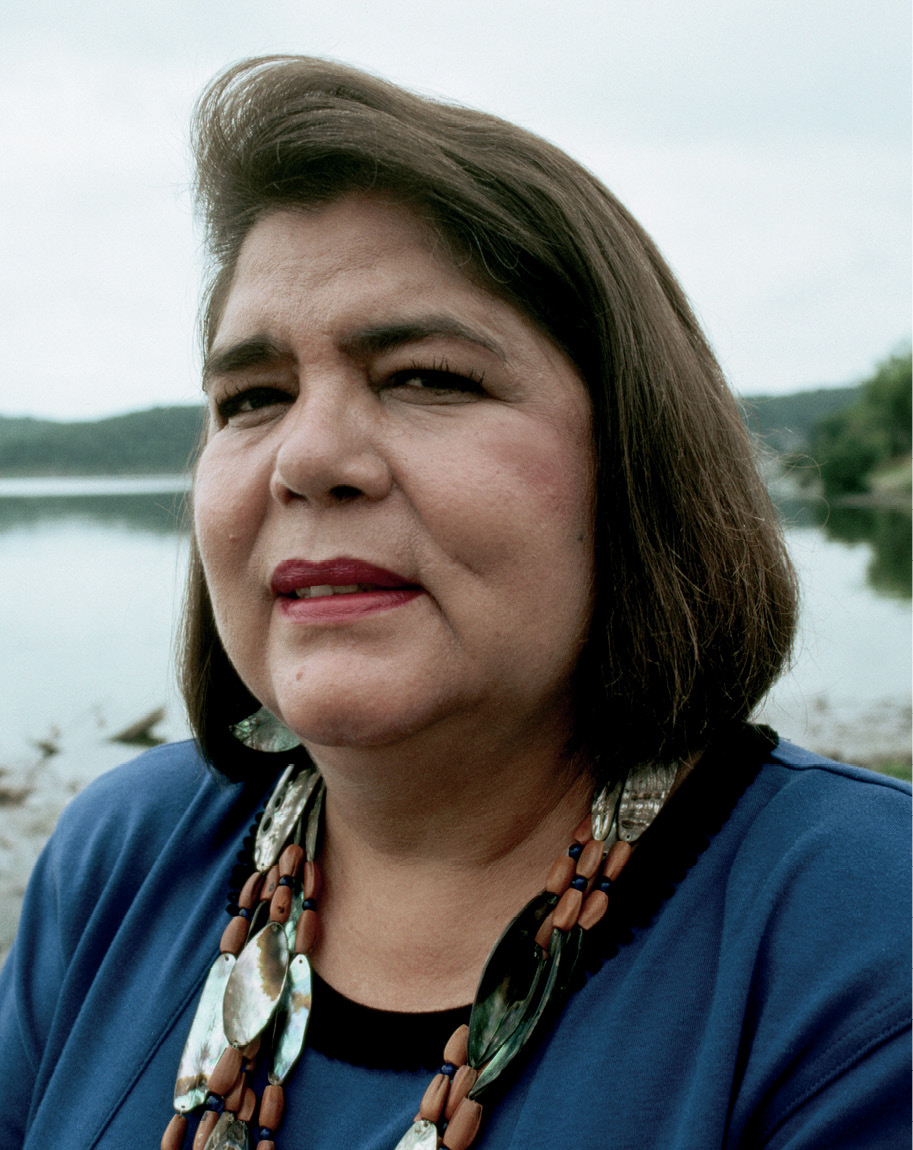

Wilma Mankiller

Hillary

Wilma Mankiller was born in 1945 in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, the capital of the Cherokee Nation. The sixth of eleven children of a full-blooded Cherokee father and a Dutch-Irish mother, she spent much of her childhood on a tract of land given to her grandfather by the government as part of a settlement for brutally forcing the Cherokee to move to Oklahoma. When she was ten years old, the government relocated her family to California; Wilma was heartbroken. Years later, she wrote in her autobiography: “I wept tears that came from deep within the Cherokee part of me… tears from my history, from my tribe’s past.”

As a teenager, Wilma found her home away from home at the San Francisco Indian Center. She married a month before her eighteenth birthday and had two daughters. The traditional role her husband expected her to play clashed with the social change she saw all around her in California in the 1960s: the women’s movement, the anti–Vietnam War movement, and the civil rights movement. When a group of Native Americans occupied the abandoned Alcatraz prison and claimed Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay “in the name of all Indian tribes” in 1969, Wilma’s life changed forever. “Just as seeing women speak up had an impact on me, seeing native people on the 6 o’clock news challenge the United States government—go and take over an island, and talk about treaty rights and the need for education and health care—had a profound impact,” she said.

Throughout the nineteen months that the group occupied the prison, Wilma brought supplies and helped raise funds and awareness. It was a turning point for Wilma; the more she did, the more involved she wanted to be with Native American issues. “When Alcatraz occurred, I became aware of what needed to be done to let the rest of the world know that Indians had rights, too. Alcatraz articulated my own feelings about being an Indian.” She started taking college classes in social work. She bought her first car, a symbol of independence. She would dance with her daughters to her favorite song, Aretha Franklin’s “Respect.”

Wilma’s husband demanded that she remain a traditional housewife—a tension she resolved by divorcing him and moving back to her grandfather’s land in Oklahoma with her daughters. Once back on the Cherokee reservation, she suffered two physical setbacks. In 1979, she was severely injured in a car accident. The driver of the other car—tragically her best friend—was killed. Wilma required nearly a year of recovery. She spent that time reflecting on her future and immersed herself in Cherokee traditions, embracing the idea of “being of good mind.” For her, that meant fighting to keep a positive outlook, even when it wasn’t easy, and searching for ways to serve. “After that,” she said, “I knew I’d lost the fear of death and the fear of challenges in my life.” Once she recovered from the accident, she was diagnosed with a neuromuscular disease that made moving difficult. Still, she never wavered from her commitment to advocating for her community.

As she put her life back together, Wilma organized a self-help project in the small village of Bell, Oklahoma, on the reservation. She engaged the community in identifying its own problems and, through their own work and Wilma’s fundraising, devising a plan to solve them. In Bell, she supervised the construction of a water system and the upgrade and renovation of substandard housing. Because of this work, Ms. magazine named her Woman of the Year in 1987. She also enrolled in courses in community development at the University of Arkansas to further her skills.

During this time, she met her second husband, a Cherokee man who supported her entry into politics. Based on her proven organizing and management skills, she was recruited to run for deputy principal chief in 1983, the first woman to vie for that position. “I expected my politics to be the issue,” she said. “They weren’t. The issue was my being a woman, and I wouldn’t have it. I simply told myself that it was a foolish issue, and I wouldn’t argue with a fool.” She overcame opposition, harsh criticism, and death threats to win the election.

“I’ve run into more discrimination as a woman than as an Indian.”

—WILMA MANKILLER

When the principal chief resigned in 1985, Wilma ascended to chief. Two years later, she ran to be elected in her own right. Once again, she faced sexist attacks. The hostility she endured surprised her because traditional Cherokee societies, families, and clans were organized through the maternal side. To deal with the sexism, she called on the traditions of Cherokee culture where women’s councils historically had participated in making social and political decisions for the tribe. In her autobiography, Mankiller: A Chief and Her People, she writes about how Cherokee and Native American women had been respected before the conquest of Native American tribes and that the imposition of the conquering culture altered the balance between men and women.

Under her leadership, the Cherokee government built new health clinics and created early education, adult learning, and job-training programs. She negotiated an agreement with the United States government to allow the tribe to manage its own finances, increased the number of enrolled members of the tribe, and improved its budget by developing factories, restaurants, and bingo operations. She also stressed the importance of caring for the environment. She was tireless in working to improve respect for Native Americans across the country. When she retired, she stayed active promoting women’s rights, tribal sovereignty, cancer awareness, and other issues.

When writing about Wilma, I can’t help but think about her tenacity. No matter how many times she got knocked down, she always got back up. She didn’t let anything stand in the way of serving and advocating for her community. Through it all, she kept a sense of humor, sometimes joking that her last name came from her reputation (it’s actually a Cherokee military term for a village guard). On April 29, 1994, she came to the White House for a historic meeting of Native American leaders. At that meeting, Wilma presented me with a piece of pottery on behalf of all the tribes assembled. She was committed to strengthening the relationships between the Cherokee people and the United States government. In 1998, my husband awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and I was proud to be there cheering her on.

“The happiest people I’ve ever met, regardless of their profession, their social standing, or their economic status, are people that are fully engaged in the world around them. The most fulfilled people are the ones who get up every morning and stand for something larger than themselves. They are the people who care about others, who will extend a helping hand to someone in need or will speak up about an injustice when they see it.”

—WILMA MANKILLER

Not content to simply pursue individual success, Wilma was also dedicated to inspiring future generations and helping them to succeed. She took part in a program through the American Association of University Women that matched Cherokee girls with career mentors in order to help raise their self-confidence and open up opportunities. “Suddenly you hear young Cherokee girls talking about becoming leaders,” she wrote. “And in Cherokee families, there is more encouragement of girls.” She understood from her own experience that celebrating tradition and looking to the future can and should go hand in hand.