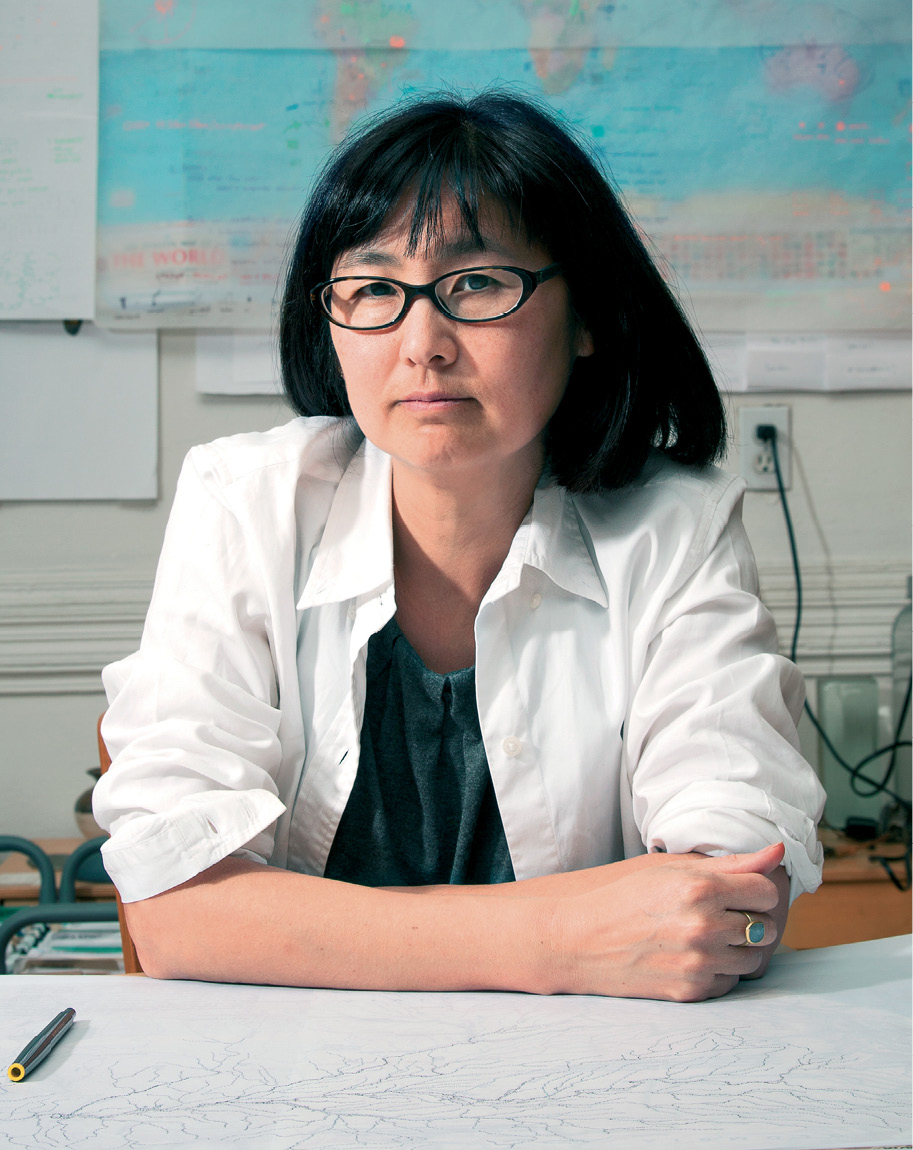

Maya Lin

Chelsea

Growing up in Ohio, Maya Lin loved working in her father’s ceramics studio, casting bronzes in her school’s foundry, and building miniature towns. She took those passions to college, studying sculpture and architecture. When she was a senior at Yale, she had the confidence to enter the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund’s national competition for the design of a new monument on Washington, D.C.’s National Mall to honor those who had fought and died in the Vietnam War. In 1981, the selection committee chose Maya’s proposal out of more than fourteen hundred submissions. Her design was simple. Two black granite walls, each close to two hundred and fifty feet long, standing at their highest above ten feet and sloping down to under a foot, all sunk below ground level. There are more than fifty-eight thousand names on the walls.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial has received countless accolades from veterans’ groups and architectural critics alike over time, including the prestigious Twenty-five Year Award from the American Institute of Architects. But when its design was chosen, it was surrounded by controversy for its simplicity, its color, and its artist—a mix of sexism, racism, and doubts that anyone so young could be charged with such an important task. But Maya believed in her design, and the selection committee stayed firm in its choice. When the Vietnam Veterans Memorial officially opened in late 1982, Maya was twenty-three years old. It is now one of the most visited memorials in Washington, D.C. Standing in front of the walls, as I have done, enables the viewer to see one’s reflection. It is a haunting and moving experience.

HILLARY

When I saw photos of the memorial, I couldn’t imagine its power. But when I first visited in the 1980s, I felt it all around me. Being surrounded by the names of the fallen and the visitors searching for their lost friends and family members is an overwhelming emotional experience. I used to visit there when I’d leave the White House, wearing a baseball cap and casual clothes for incognito walks around the Mall.

After finishing her graduate studies, Maya continued creating important public art pieces. The Women’s Table at Yale chronicles the number of women at that institution from its founding in 1701 until 1993, the year the sculpture was completed; women’s enrollment would surpass men’s in the first-year class for the first time two years later, in 1995. The Civil Rights Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama, is a memorial fountain with the names of forty people killed from 1954 to 1968 while courageously fighting for civil rights in the United States. It includes the name of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and his iconic quote “Until justice rolls down like water and righteousness like a mighty stream.” In my early twenties, I took a friend who was planning to do a PhD in history on a road trip across the South. The Civil Rights Memorial was one of many stops in Montgomery, and one of the most memorable and moving of our trip.

Maya has said her virtual memorial, What Is Missing?, will be her last memorial. What Is Missing? aims to raise awareness about the growing number of endangered species around the world and the growing crisis of a sixth extinction (the argument that we are in the middle of a man-made mass extinction event). It is poignant and appropriately alarming; I hope it is also galvanizing.

HILLARY

Ever since Chelsea was a little girl, she has worried about what happens to endangered animals like whales and elephants. Inspired by a whaling trip when she was seven, she asked for a membership to Greenpeace as a Christmas present. And in 2019, she wrote a children’s book about species going extinct: Don’t Let Them Disappear.

Maya’s interest in environmental conservation started at a young age; in elementary school, she promoted a boycott of Japan to oppose their whaling practices and dreamed of being a zoologist. Today, in addition to What Is Missing?, she is part of the Confluence Project, an effort to connect people to the Columbia River ecosystem in the Pacific Northwest through indigenous communities and voices. She has said she hopes to help stop us from degrading our planet and is optimistic that art can change the way people think, including, presumably, how we think of our relationship and responsibility to nature. That conviction is also evident in her “wavefields,” which are exactly as they sound, stunning waves built out of grass and soil. On a trip to the Storm King Art Center in New York, I was mesmerized and disoriented by the seven almost-four-hundred-feet-long ripples of earth seeming to form waves in motion. All I could do was wonder: How did the ocean merge with solid ground?

For almost my entire life, Maya’s work has given us different ways to look at the world, confront our past, and imagine a different, healthier, more sustainable and just future. With guts, humility, and compassion, Maya poses a question to all of us: What more can, and must, we do?