EIGHT

THE DARK MIRROR WAS ELEGANT, EXTRAVAGANT. ONCE Gretchen got close she could see that the frame was composed of wood carved into gilt vines and leaves, and also faces—cherubs, demons, little girls. Some of them were smiling happily, some of them weeping. Gretchen stared, awed by its intricacies. But on closer inspection, she could see the mirror was badly damaged. The frame had looked painted black, but really it seemed to have been charred in a fire. When she looked into the glass, the reflection that stared back seemed to have a double. Her own image haloed in another image of a girl. Or like there was a face behind her face. There were clear patches in the glass that weren’t reflective at all. It reminded her of looking into water—not looking at something solid, but looking at things submerged in water. For one irrational second she thought it was not a mirror but like a pond teeming with life that couldn’t be seen until it surfaced.

“Be careful,” her aunt said sharply, then seeming to catch herself, mumbled, “it’s very old.”

“It’s incredible,” Gretchen said, still uneasy about what she’d seen or not seen in it, and the obvious strangeness of the mirror having been pulled from some kind of wreckage.

“It will be hard to move,” her aunt said. “But you must take it with you. It can’t be left behind. I’m sure Hawk Green can help you lift it. You know Hawk? Course you don’t—you just got here, what am I thinking? He lives up the road . . .”

“I can’t possibly take this anywhere,” Gretchen said. “Why don’t you sell some of this stuff, Aunt Esther? I can help you list it on eBay or we can contact a collector.”

“You can do what you think is best,” Esther said. “I’m out of here.”

If Esther’s tone hadn’t been so easy and forthright she might have thought the woman was scared of something, or that she only had a few weeks to live.

“Don’t worry,” Esther said, as if reading Gretchen’s mind. “I don’t have a disease or anything like that. I’m not contagious.”

Gretchen turned back to the mirror, touched it, and then drew her hand away quickly. It was freezing, as if it were made of ice.

She looked more closely at the ornate faces of little girls carved into the frame; some of them were smiling, but some of them seemed, indeed, to be screaming or to be devils and not little girls at all. The vines were wrapped around their necks, tangled in their hair. Gretchen thought the mirror must be from the Victorian era. Her mother had taught her all about the Victorians. Back then, women wore necklaces woven from the hair of their dead loved ones. People displayed photographs of the bodies of their recently dead relatives—sometimes sitting up in chairs with their eyes wide open—on their mantels. They held séances and played with Ouija boards as commonly and casually as people watched Fresh Prince reruns and played Scrabble today.

She peered into it again, looking for what she might have seen. Then she stepped back, looked at her own mottled reflection. Her hair was a mess from having the window down on the drive and it looked very punk-chic, coming out of the topknot. She leaned in closer and it seemed another face was rising to the surface of the glass, just as she had imagined. Like it was rising from deep within a well, she watched the face open its mouth as if to scream.

Startled, Gretchen stepped back quickly; she had not opened her mouth or spoken a word. She whipped her head around to see what the mirror might be reflecting. Nothing there.

“See something?” Esther asked, squinting. “That’s a funny old mirror, isn’t it?”

Gretchen told herself she was just tired. It had been a long trip and she needed to eat something and then call Simon, maybe take some of the money Janine had given her and go book herself into a hotel. She’d yawned, was all, had opened her mouth without realizing it. She’d been scared of nothing but her own tired reflection.

Esther pointed through the door across from the mirror.

“Here’s your room,” she said. “The others are more . . . cluttered. This used to be the library.”

A new moldering smell—this time more bookshop than thrift store. The room was astonishing. Bookcases from floor to ceiling on three walls held thousands of books, old hardcovers, but contemporary-looking titles too—bright covers and paperbacks and dusty leather-bound tomes, a heavy oak table covered with papers and books and boxes of old photographs. Surrounded by three chairs, all carved in the same manner as the mirror. In the corner by the window there was an ornate four-poster bed with a quilt made of red and pale-blue triangles. A mosquito net hung delicately down over it and an old Persian rug sat at the foot.

“For the wasps, not mosquitos,” Esther said.

“I thought you said they didn’t sting.”

“I said I never got stung,” Esther said. “There’s a difference.”

Dingy moth-eaten lace curtains hung before leaded glass windows, facing the west, and sunlight was pouring through—maybe the door had been open a crack and the orange sunlight had reflected in the mirror and caused some trick of the light in the mirror. Gretchen was embarrassed she’d been scared by the mirror, embarrassed that she still felt scared, could feel the chill of the glass as if it had penetrated into her bones.

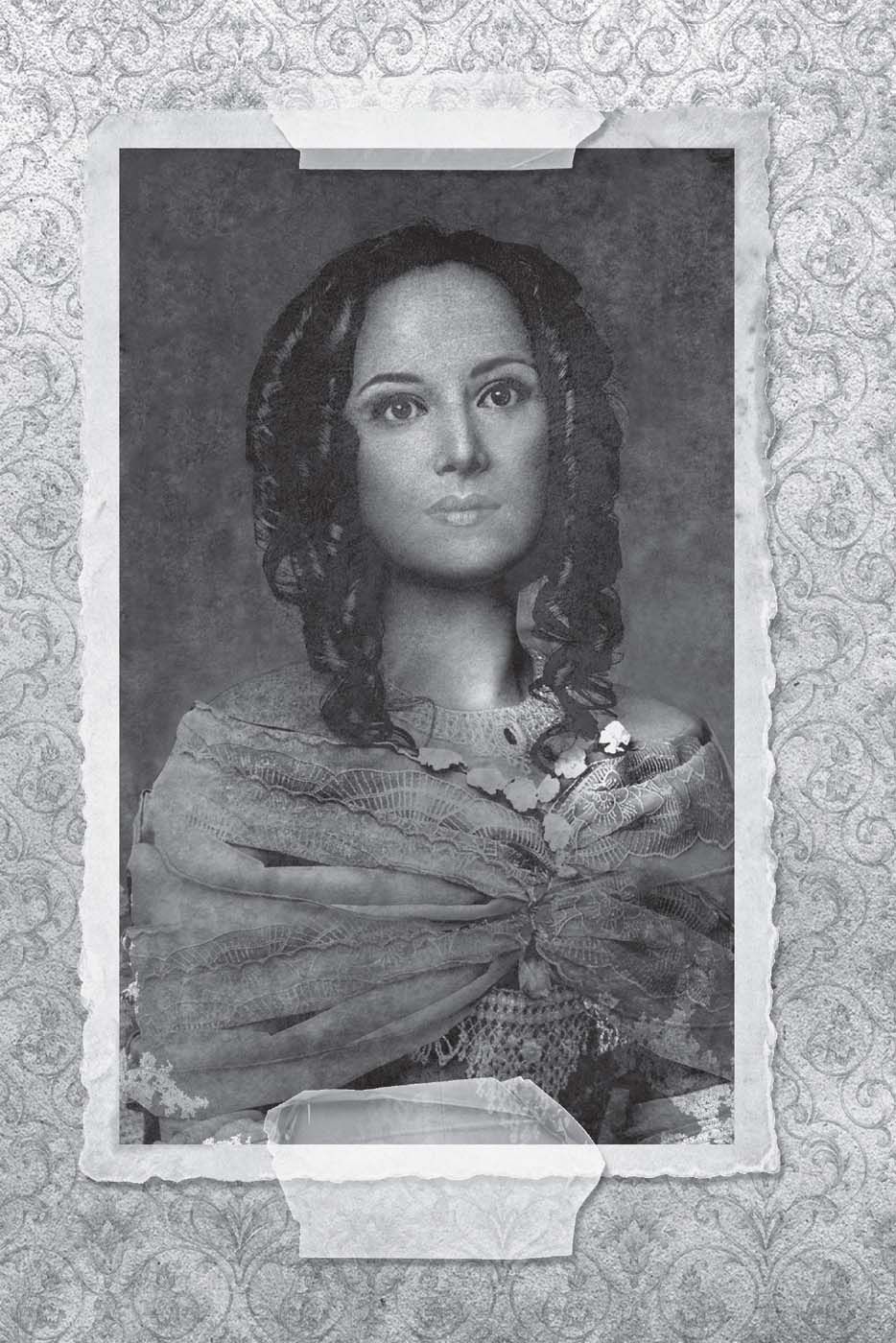

“I hope you’ll be happy here,” her aunt said. She stepped over to the wall, and pointed to two sepia-tinted portraits framed in black. “These are your great-great-great-great-grandparents, Fidelia and George Axton.”

In the portraits they were very young. Fidelia had dark eyes like Gretchen’s mother and the same shape face; it was uncanny how similar the expression was, amused but reserved, thoughtful. But her hair was certainly not the same as Mona’s wild curly mane. She’d had it combed down painfully straight and pulled back.

“Fidelia,” Gretchen said. “Was that a popular name?”

“I don’t know,” Esther said.

“My mother gave me an old journal by someone named Fidelia Moore, when I was a kid.”

Esther laughed. “What a coincidence,” she said playfully, looking at Gretchen like she was a little slow. “That happens to be your great-great-great-great-grandmother’s maiden name. And she kept plenty of journals. Years’ worth.”

Gretchen took a breath. “This is that Fidelia?” Seeing a photograph of the woman whose personal thoughts she’d read (and often mocked), while standing in the ruin that had been the woman’s home, was unsettling. Especially because there was such a strong family resemblance—she could recognize the slope of her own nose on Fidelia’s face. Why hadn’t her mother told her the journal had come from their family? The entries she’d read were from when the woman was in her teens. In the picture she didn’t look much older than that, but was already married.

“And this is her husband?” Gretchen asked.

“It is.” Esther raised her eyebrows. “Charming-looking chap, eh?” she said sarcastically. Where Fidelia looked thoughtful and alive, George looked blank, a wealthy man with fancy clothes and no personality. Based on the photos, no one would have said they were well matched.

“Listen,” Esther said. “All the family history has been collected in this room—most of the documents, anyway, journals, schoolwork, newspapers, letters; I haven’t had a chance to go through it all. But everything’s here . . . somewhere. More or less . . .” She opened a drawer in a side table and pulled out a small bundle, handed it to Gretchen. It was a pile of letters with ornate script, the envelopes of which Gretchen could barely read. They were tied up in a black ribbon.

“These were written by Fidelia.”

Gretchen was fascinated. Here at her fingertips was the entire history of her family. She touched the faded ink on the front of the first letter, then stared up at the picture of Fidelia.

“Thank you,” she said to Esther, and as if she were offering the woman a gift in exchange, she picked up her camera and took a picture of Esther sitting there beneath the portrait of Fidelia. That made Esther smile.

The house itself was one of the best subjects for a photo essay she could imagine. She leaned out the window near the monstrous rose thicket that grew alongside the house, and aimed her camera up the road at a little white house that looked like something from a fairy tale. Framed by the window and accented by the rosebush, it would be a lovely picture.

“Who lives there?” Gretchen asked.

“Hawk,” she said, as if it were obvious and Gretchen already knew. “And his sister. I think you’ll like them. Listen, sweets. I don’t mean to rush you, but we have to get down to business here. For a long time your mother had been planning to go through this entire archive. She started some years ago but left abruptly before finishing it,” Esther said. “And frankly someone has to do it, and it might as well be the heiress apparent. We’re hoping for some clues, for anything that could help.”

“She was here?” Gretchen asked. “She was . . . clues for what?” Things were beginning to seem even more surreal.

“Mona came here every year,” Esther said. “She was looking for—”

“When was the last time she came out here?” Gretchen interrupted.

Esther thought about it. “Five, six years ago maybe. She was taking pictures of the land. She must have told you about what happened here, right? What she was doing?”

“No.”

“No?” Now it was Esther’s turn to look shocked, then simply exhausted. Her chin crumpled and she turned away.

“I know this is where she started thinking about spirits,” Gretchen said quickly, not wanting the old woman to shut down. But honestly, what did Esther expect? Until yesterday Gretchen had only the vaguest notion that Esther even existed, or that the house was still in their family.

“She showed me a picture she thought had a ghost in it when I was a little kid,” Gretchen said. “Her brother’s ghost, she said. Now that I’ve been shooting for a while I think it was probably a double exposure, or a mix-up at the processing place—it was from the seventies. . . .”

“Yes, yes, Piper,” Esther said. “He died in an accident. Accidents seem to be the number-one cause of death here, especially this time of year. This was something your mother was very keen on studying, and documenting.”

“Why?”

“Now listen to me, sweets,” Esther said. “We don’t have too much time, and you have a lot to learn. Did your mom mention anything else about the house?”

Gretchen shook her head. “Just that her parents left it and never went back.” She was dying for Esther to go on—to find out anything that might give her the slightest hint of what could have happened to her mother or where she could be.

“Well, before all of that,” Esther said, “our relatives were abolitionists.”

“Wow, really?” Gretchen walked across the creaking floor and sat in one of the old carved chairs. “I had no idea.”

Esther smiled, but there was something sad underneath it. “Your great-great-great-great-uncle James was a pastor of a church he built on this property. His brother was your great-great-great-great-grandfather—George—the guy in the picture. The church was a safe house on the Underground Railroad. Fidelia and James and George would hide people there and then help them settle in the north or get to Canada safely. James preached liberation theology—how Jesus wanted all men to be free and have no masters. He had one of the first fully integrated congregations in the country.”

All of this was very interesting, but Gretchen was impatient. She didn’t see what it had to do with accidents or Mona going missing. And then that feeling she thought was gone came surging back. The feeling that maybe she would stumble upon the truth hidden in some everyday moment or conversation and be able to find her mother herself. Mona had stood in that very room, digging through these archives. Why, she wondered, had neither of her parents ever mentioned the extent of the Axton family’s history in Mayville? Especially when it was so important to her mother—important enough to go there every year without telling a soul. As far as she knew it was a secret even from her father.

“When the Civil War started,” Esther went on, “James went off to fight and left George here to be pastor of the church.”

“You can just do that?” she asked skeptically. “You can just be, like . . . I’m leaving, so you’re the pastor now, tell everyone Jesus hates bigots?” Gretchen asked.

“Hush,” Esther said. “Don’t be a wise ass. Where was I? Oh . . . in any case, George kept working in the family business, and presumably kept up the mission of the church. He and Fidelia got married and had two children, Celia and Adam, and from what we know they kept helping people escape slavery, bringing them through here. Some even settled in the town eventually.

“And then everything went to hell. We don’t know exactly what happened. The church was burned to the ground. We don’t even know how many were killed, though some think it could have been half the congregation. The entire thing was ruled an accident. But it’s obvious it was white supremacists. No one knows how they found out it was a safe house. No one did anything to put out the fire or to save the people who were trapped inside.” Esther looked down and shook her head, lit a cigarette. “An accident,” she said with disgust.

A shiver went through Gretchen. She thought about people finally broken free of their torturers in the South, then terrorized, hiding in the church, only to die here in the north, murdered by the same kind of racists they’d escaped. She thought of the people who did nothing—made it possible for the racists and Klan to grow stronger, to get away with killing the innocent.

“Fidelia and her daughter, Celia, also died in the fire,” Esther said.

“They were African American?” Gretchen asked, as she looked again at the portrait. It was sepia-toned, and difficult to make out Fidelia’s complexion. Esther shook her head. “No. They were the only white people who died that day.”

Gretchen stood and walked to the middle of the room, suddenly restless. And people think New York City is violent, she thought. They think that things are so quaint and wholesome in the country, or back in the past.

“The Axtons held on to the house through all of that?” Gretchen said.

“Well, the family business was still thriving, of course,” Esther said. “The Axtons made a lot of money shipping goods overseas. After that the church was never rebuilt and life just went on, business as usual.”

“But why would anyone want to keep living here? I can’t imagine living on the site of that kind of crime.”

“Come now, sweets,” Esther said, looking at her with weary incredulity. “There are few places in the world that aren’t soaked with blood when you take a close look. And people need a place to live.”

“So the house was passed on through George? Did he remarry?”

“No,” Esther said. “George stayed here and raised the little boy—Adam—the only descendant who lived through all the violence; he was an infant at the time and home with a nanny.”

“And is there somehow . . . is there a link between this and my mother disappearing?” Gretchen thought of some centuries-old cover-up her mother might have discovered.

“Maybe a lot,” Esther said, a strange expression beginning to cloud her face. “But you look exhausted, and I’ve talked your ear off since you got here. I’ll tell you more after you get settled in.”

Gretchen nodded, even though she couldn’t imagine getting settled in a place so dilapidated. She wanted to know more right away. And to be able to give it all the proper thought and scrutiny. She could see why her mother would have wanted to study their family history more—document it—but the idea that anything that happened over a century ago was tied to her mother’s disappearance seemed sketchy, and maybe this tale of fire and freedom fighters, which she’d never heard before, wasn’t even true. A prominent wealthy family running a safe house for the Underground Railroad? A particularly brutal killing of escaped slaves? She’d never encountered it in a New York State history class, even a story that said it was an accident, and it seemed like the kind of historical event that would be written about.

Esther stood to leave.

“Wait, Aunt Esther,” Gretchen said. “Why have you stayed here all this time?”

“There’s much to be said for having a roof over your head,” Esther said. “Listen, sweets, good things happened here too. Hundreds of people who’d been enslaved got to freedom through this house and the church, and they went on to have children, generations of people, some who still live around here. Those are a couple reasons I stay. The others we’ll talk about over a good stiff drink.”

Gretchen thought about her aunt out here alone in this enormous house surrounded by miles of forest, on the site of a massacre. Crazy or not, she was a brave old lady.

“You get settled in,” said Esther. “I’ll go make us some cocktails. The washroom is down the hall, and my room is right above yours. But we’ll save the tour for later.”

Gretchen tried to smile. She wished Esther had said something about dinner instead of drinks. Suddenly she was very hungry, and this made her miss the city, where you could just step out the door and get something delicious right away. Asian fusion or Indian would be wonderful right now. She was about to suggest they go out to eat and then stay in a hotel, get a fresh start on archiving in the morning. But when she looked up at Aunt Esther, the woman was smiling at her with such love and old-lady coolness, she felt embarrassed to bring it up. She couldn’t remember the last time anyone had seemed this happy to see her, to be with her—except, of course, Simon. And there was that shadow of her mother’s face she could see in Esther’s, and the shadow of Fidelia in all of them. It melted her skepticism, made her want to learn more—even if all she’d find out was that Esther’s various ideas about accidents and church burnings were because she had dementia. She’d stay. At least for the night. Go through the letters Esther had given her, start looking at what her mother had been collecting. Tomorrow she’d give Esther the kind of help she really needed: find out about hiring a cleaning crew, maybe get an antique appraiser to have a look around. Maybe even see if there was a doctor who could give her a checkup. Her father’s mother had dementia and she had nurses living with her to help her. Country people always thought they had to do everything themselves—a lifetime of not being able to order takeout probably does that to you, Gretchen thought.

Once Esther had gone downstairs Gretchen went out into the hall and looked at the mirror again. The surface was smoky and mottled and it distorted her reflection. It seemed to have a magnetic pull. Not like an actual magnet, but the way cool water feels on a hot day, draws you to it. The wasps buzzed from inside the vase but she wasn’t afraid of them. She reached out again to the mirror and watched the reflected hand reach toward her. Then, again as if it were rising from water—she saw her own face, distorted by the mottled surface, her eyes looking like they were trying to tell her something she couldn’t yet understand. Her skin broke out in goose bumps and she tore herself away from the mirror’s pull.

This awful thing, Gretchen thought, will be the first to go up on eBay. She went back into the library and shut the door.

Gretchen didn’t bother to unpack but sat on the creaky bed and looked around. There were boxes and boxes of photographs and letters. The bookshelves were stuffed with cracked leather-bound books. Shelves full of classics, and also academic books, historical tomes, great novels. This was one of the last places her mother had been; she was surrounded by the things Mona had amassed to study and could almost feel her presence. The Axtons had once filled this mansion, generation after generation. Now there was just her and Esther. The idea of going through the library for clues to something she barely understood was daunting. But it was as close as she’d ever come to any lead on her mother. She flopped back on the bed and stared up at the ceiling.

The afternoon sunlight shifted as the curtain blew in the breeze and something on top of one of the tall glass-front bookcases caught her eye. It looked like a hatbox, and she realized that probably all the clothes people had worn were also still in the house. She had always been fascinated with vintage clothes. She walked over and stood on tiptoe to take it down, and when she opened it, she found a very well-preserved hat. It had a double black-lace-scalloped border and a shiny black bow in the back. She opened the door to the musty closet and indeed there were hangers full of dresses, and more boxes on the floor. She touched a gauzy pink skirt topped with a narrow bodice and it nearly came apart in her hand, delicate and brittle and worn through from age and neglect.

Crouching, she opened a few of the boxes to find shoes in a size that seemed impossibly small. In a taller square box with a plain white card affixed to the top she uncovered something else: a pile of leather-bound books, all tied together with a black ribbon with a round locket at the end of it. She opened the locket. Inside there was what appeared to be a small clump of lint, but no, that wasn’t it. It was hair that looked like it had come from two different heads, tied in a bow. On the inside of the locket someone had written R & C in a beautiful calligraphic hand. She snapped it shut.

The books beneath the ribbon turned out to be journals. Pages and pages all written in that same elegant handwriting she had read over as a girl, some of the pages dark with mold, the pages completely illegible; others were perfectly preserved. It was remarkable. Her mother had given her Fidelia’s journal from when she was in her early teens, and here Gretchen was, nearly grown herself, discovering the rest of them. The years that chronicled Fidelia’s days of cooking and sewing and caring for children. She cracked another one open. And breathed in the smell of decaying paper and fading ink—and her heart raced.

February 17, 1860

Last night James returned with a young man—or perhaps not a man yet, still a child. He wore coarse fabric over his head like a hood to cover himself, and he had taken off his shirt to cover an old woman. She was so small that at first I thought he was holding only a checkered cloth in his arms. I said to follow me, but he indicated that he could not, another was still to come, and soon she ran from the trees in a dress too long for her. Perhaps five years of age, with bright eyes as if a candle had been lit behind them. I had no time to ask her name, only to tell her to hurry after me. I felt shame and rage that anyone could treat a person as she’d been treated. George told me this morning that these three belong to a Mr. Grant, of Baltimore, who offers one hundred dollars of reward for the return of the boy and the girl together. Or fifty dollars each. The old woman he no longer needs.

She stood for a moment, stunned to be holding this kind of artifact in her hands. Esther wasn’t just making things up. Gretchen thought about her ancestors—how good they were, or maybe simply so guilty they couldn’t bear to watch any more pain. She looked up again at the portrait of Fidelia and for the first time felt a connection to her roots, or maybe to the roots of all women fighting for something they believed in.

Gretchen checked her phone, dying to talk to Simon, and—at last!—there was full reception in this room.

She took a picture with her phone of the wall of books and portraits, the rosebush just visible out the window and tattered curtains blowing in the breeze, and sent it to Simon with the understated message I’m here. Three seconds later he replied, OMFG insane!

“You don’t know the half of it,” she whispered, then headed downstairs.

Dear James,

How are your studies? I was happy to hear you received the mittens! I bought so much wool from Elias’s farm that I have been knitting up a storm. It’s good to have something to do with my hands as I find myself quite restless. Reading the papers you send is a joy, though it makes me even more eager to be by your side. To be engaged in meaningful work.

I’m wondering if it would not be too presumptuous of me to ask you to send me some books. You know too well that the quality and variety of books here in Mayville leaves something to be desired and I fear becoming a sheltered country mouse! My father has even forbidden me a subscription to the NEW YORK EVENING POST. Were it not for our friendship, James, or the conversations with the ladies who tend the sheep at Elias’s, I would be even more badly informed.

Yours,

Fidelia