VII

I MENTIONED PREVIOUSLY that only the covenantal community consisting of all three grammatical personae—I, thou, and He—can and does alleviate the passional experience of Adam the second by offering him the opportunity to communicate, indeed to commune with, and to enjoy the genuine friendship of Eve. Within the covenantal community, I said, Adam and Eve participate in the existential experience of being, not merely working, together. The change from a technical utilitarian relationship to a covenantal existential one occurs in the following manner. When God joins the community of man the miracle of revelation takes place in two dimensions: in the transcendental— Deus absconditus emerges suddenly as Deus revelatus—and in the human— homo absconditus sheds his mask and turns into homo revelatus. With the sound of the divine voice addressing man by his name, be it Abraham, Moses, or Samuel, God, whom man has sought along the endless trails of the universe, is discovered suddenly as being close to and intimate with man, standing just opposite or beside him. At this meeting—initiated by God—of God and man, the covenantal-prophetic community is established. When man addresses himself to God, calling Him in the informal, friendly tones of “Thou,” the same miracle happens again: God joins man and at this meeting, initiated by man, a new covenantal community is born—the prayer community.

I have termed both communities, the prophetic and the prayerful, covenantal because of a threefold reason. (1) In both communities, a confrontation of God and man takes place. It is quite obvious that the prophecy awareness, which is toto genere different from the mystical experience, can only be interpreted in the unique categories of the covenantal event. The whole idea of prophecy would be fraught with an inner contradiction if man’s approach to God remained indirect and impersonal, expecting nature to mediate between him and his Creator. Only within the covenantal community, which is formed by God descending upon the mount* and man, upon the call of the Lord, ascending the mount,* is a direct and personal relationship expressing itself in the prophetic “face-to-face” colloquy established. “And the Lord spake unto Moses face to face as man speaketh unto his friend.”†

Prayer likewise is unimaginable without having man stand before and address himself to God in a manner reminiscent of the prophet’s dialogue with God. The cosmic drama, notwithstanding its grandeur and splendor, no matter how distinctly it reflects the image of the Creator and no matter how beautifully it tells His glory, cannot provoke man to prayer. Of course, it may arouse an adoring-ecstatic mood in man; it may even inspire man to raise his voice in a song of praise and thanksgiving. Nevertheless, ecstatic adoration, even if expressed in a hymn, is not prayer. The latter transcends the bounds of liturgical worship and must not be reduced to its external-technical aspects such as praise, thanksgiving, or even petition. Prayer is basically an awareness of man finding himself in the presence of and addressing himself to his Maker, and to pray has one connotation only: to stand before God.* To be sure, this awareness has been objectified and crystallized in standardized, definitive texts whose recitation is obligatory. The total faith commitment tends always to transcend the frontiers of fleeting, amorphous subjectivity and to venture into the outside world of the well-formed, objective gesture. However, no matter how important this tendency on the part of the faith commitment is—and it is of enormous significance in the Halakhah, which constantly demands from man that he translate his inner life into external facticity—it remains unalterably true that the very essence of prayer is the covenantal experience of being together with and talking to God and that the concrete performance such as the recitation of texts represents the technique of implementation of prayer and not prayer itself.1 In short, prayer and prophecy are two synonymous designations of the covenantal God–man colloquy. Indeed, the prayer community was born the very instant the prophetic community expired and, when it did come into the spiritual world of the Jew of old, it did not supersede the prophetic community but rather perpetuated it. Prayer is the continuation of prophecy, and the fellowship of prayerful men is ipso facto the fellowship of prophets. The difference between prayer and prophecy is, as I have already mentioned, related not to the substance of the dialogue but rather to the order in which it is conducted. While within the prophetic community God takes the initiative—He speaks and man listens—in the prayer community the initiative belongs to man: he does the speaking and God, the listening. The word of prophecy is God’s and is accepted by man. The word of prayer is man’s and God accepts it. The two Halakhic traditions tracing the origin of prayer to Abraham and the other Patriarchs and attributing the authorship of statutory prayer to the men of the Great Assembly reveal the Judaic view of the sameness of the prophecy and prayer communities.* Covenantal prophecy and prayer blossomed forth the very instant Abraham met God and became involved in a strange colloquy. At a later date, when the mysterious men of this wondrous assembly witnessed the bright summer day of the prophetic community, full of color and sound, turning to a bleak autumnal night of dreadful silence unillumined by the vision of God or made homely by His voice, they refused to acquiesce in this cruel historical reality and would not let the ancient dialogue between God and men come to an end. For the men of the Great Assembly knew that with the withdrawal of the colloquy from the field of consciousness of the Judaic community, the latter would lose the intimate companionship of God and consequently its covenantal status. In prayer they found the salvation of the colloquy, which, they insisted, must go on forever. If God had stopped calling man, they urged, let man call God. And so the covenantal colloquy was shifted from the level of prophecy to that of prayer.

(2) Both the prophetic and the prayerful communities are threefold structures, consisting of all three grammatical personae—I, thou, and He. The prophet in whom God confides and to whom He entrusts His eternal word must always remember that he is the representative of the many anonymous “they” for whom the message is earmarked. No man, however great and noble, is worthy of God’s word if he fancies that the word is his private property not to be shared by others.*

The prayerful community must not, likewise, remain a twofold affair: a transient “I” addressing himself to the eternal “He.” The inclusion of others is indispensable. Man should avoid praying for himself alone. The plural form of prayer is of central Halakhic significance.† When disaster strikes, one must not be immersed completely in his own passional destiny, thinking exclusively of himself, being concerned only with himself, and petitioning God merely for himself. The foundation of efficacious and noble prayer is human solidarity and sympathy or the covenantal awareness of existential togetherness, of sharing and experiencing the travail and suffering of those for whom majestic Adam the first has no concern. Only Adam the second knows the art of praying since he confronts God with the petition of the many. The fenced-in egocentric and ego-oriented Adam the first is ineligible to join the covenantal prayer community of which God is a fellow member. If God abandons His transcendental numinous solitude, He wills man to do likewise and to step out of his isolation and aloneness.* Job did not understand this simple postulate. “And it was so, when the days of their feasting were gone about, that Job sent and sanctified them, and rose up early in the morning, and offered burnt offerings according to the “number of them all.”† He did pray, he did offer sacrifices, but only for his household. Job failed to understand the covenantal nature of the prayer community in which destinies are dovetailed, suffering or joy is shared, and prayers merge into one petition on behalf of all. As we all know, Job’s sacrifices were not accepted, Job’s prayers remained unheard, and Job—pragmatic Adam the first— met with catastrophe and the whirlwind up-rooted him and his household. Only then did he discover the great covenantal experience of being together, praying together and for one another. “And the Lord turned the captivity of Job, when he prayed for his friends; also the Lord gave Job twice as much as he had before.” Not only was Job rewarded with a double measure in material goods, but he also attained a new dimension of existence—the covenantal one.

(3) Both communities sprang into existence not only because of a singular experience of having met God, but also and perhaps mainly because of the discovery of the normative kerygma entailed in this very experience. Any encounter with God, if it is to redeem man, must be crystallized and objectified in a normative ethico-moral message. If, however, the encounter is reduced to its non-kerygmatic and non-imperative aspects, no matter how great and magnificent an experience it is, it cannot be classified as a covenantal encounter since the very semantics of the term “covenant” implies freely assumed obligations and commitments. In contradistinction to the mystical experience of intuition, illumination, or union which rarely results in the formulation of a practical message, prophecy, which, as I emphasized before, has very little in common with the mystical experience, is inseparable from its normative content. Isaiah, Ezekiel, or other prophets were not led through the habitations of heaven, past the seraphim and angels, to the hidden recesses where God is enthroned above and beyond everything in order to get the overpowering glimpse of the Absolute, True, and Real, and to bring their individual lives to complete fulfillment. The prophetic pilgrimage to God pursues a practical goal in whose realization the whole covenantal community shares. When confronted with God, the prophet receives an ethico-moral message to be handed down to and realized by the members of the covenantal community, which is mainly a community in action. What did Isaiah hear when he beheld God sitting on the throne, high and exalted? “Also I heard the voice of the Lord saying, ‘Whom shall I send and who will go for us…?’” What did Ezekiel hear when he completed his journey through the heavenly hierarchy to the mysterious sanctuary of God? “And He said unto me: son of man, I send thee to the children of Israel, to a rebellious nation that hath rebelled against me.…” The prophet is a messenger carrying the great divine imperative addressed to the covenantal community. “So I turned and came down from the mount.… And the two tablets of the covenant were on my two hands.” This terse description by Moses of his noble role as the carrier of the two tablets of stone on which the divine norm was engraved has universal significance applicable to all prophets.* “I will raise them up a prophet… and will put my words into his mouth.…Whosoever will not hear unto my words which he shall speak in my name, I will require of him.”

The above-said, which is true of the universal faith community in general, has particular validity for the Halakhic community. The prime purpose of revelation in the opinion of the Halakhah is related to the giving of the Law. The God–man confrontation serves a didactic goal. God involves Himself in the covenantal community through the medium of teaching and instructing. The Halakhah has looked upon God since time immemorial as the teacher par excellence.* This educational task was in turn entrusted to the prophet whose greatest ambition is to teach the covenantal community. In short, God’s word is ipso facto God’s law and norm.

Let me add that for Judaism the reverse would be not only unthinkable but immoral as well. If we were to eliminate the norm from the prophetic God–man encounter, confining the latter to its apocalyptic aspects, then the whole prophetic drama would be acted out by a limited number of privileged individuals to the exclusion of the rest of the people.* Such a prospect, turning the prophetic colloquy into an esoteric-egotistic affair, would be immoral from the viewpoint of Halakhic Judaism, which is exoterically-minded and democratic to its very core. The democratization of the God–man confrontation was made possible by the centrality of the normative element in prophecy. Only the norm engraved upon the two tablets of stone, visible and accessible to all, draws the people into this confrontation “Ye are placed this day, all of you, before the Eternal, your God; your heads of your tribes, your elders and your bailiffs, with all the men of Israel…from the hewer of thy wood unto the drawer of thy water.” And how can the woodchopper and the water drawer participate in this adventurous meeting of God and man, if not through helping in a humble way to realize the covenantal norm?

Prayer likewise consists not only of an awareness of the presence of God, but of an act of committing oneself to God and accepting His ethico-moral authority.2

Who is qualified to engage God in the prayer colloquy? Clearly, the person who is ready to cleanse himself of imperfection and evil. Any kind of injustice, corruption, cruelty, or the like desecrates the very essence of the prayer adventure, since it encases man in an ugly little world into which God is unwilling to enter. If man craves to meet God in prayer, then he must purge himself of all that separates him from God. The Halakhah has never looked upon prayer as a separate magical gesture in which man may engage without integrating it into the total pattern of his life. God hearkens to prayer if it rises from a heart contrite over a muddled and faulty life and from a resolute mind ready to redeem this life. In short, only the committed person is qualified to pray and to meet God. Prayer is always the harbinger of moral reformation.3

This is the reason why prayer per se does not occupy as prominent a place in the Halakhic community as it does in other faith communities, and why prayer is not the great religious activity claiming, if not exclusiveness, at least centrality. Prayer must always be related to a prayerful life which is consecrated to the realization of the divine imperative, and as such it is not a separate entity, but the sublime prologue to Halakhic action.

If God had not joined the community of Adam and Eve, they would have never been able and would have never cared to make the paradoxical leap over the gap, indeed abyss, separating two individuals whose personal experiential messages are written in a private code undecipherable by anyone else. Without the covenantal experience of the prophetic or prayerful colloquy, Adam absconditus would have persisted in his he-role and Eve abscondita in her she-role, unknown to and distant from each other. Only when God emerged from the transcendent darkness of He-anonymity into the illumined spaces of community knowability and charged man with an ethical and moral mission, did Adam absconditus and Eve abscondita, while revealing themselves to God in prayer and in unqualified commitment, also reveal themselves to each other in sympathy and love on the one hand and in common action on the other. Thus, the final objective of the human quest for redemption was attained; the individual felt relieved from loneliness and isolation. The community of the committed became, ipso facto, a community of friends—not of neighbors or acquaintances. Friendship—not as a social surface-relation but as an existential in-depth-relation between two individuals—is realizable only within the framework of the covenantal community, where in-depth personalities relate themselves to each other ontologically and total commitment to God and fellow man is the order of the day. In the majestic community, in which surface personalities meet and commitment never exceeds the bounds of the utilitarian, we may find collegiality, neighborliness, civility, or courtesy—but not friendship, which is the exclusive experience awarded by God to covenantal man, who is thus redeemed from his agonizing solitude.

Majestic man is not confronted with this time dilemma. The time with which he works and which he knows is quantified, spatialized, and measured, belonging to a cosmic coordinate system. Past and future are not two experiential realities. They just represent two horizontal directions. “Before” and “after” are understandable only within the framework of the causal sequence of events.* Majestic man lives in micro-units of clock time, moving with ease from “now” to “now,” completely unaware of a “before” or an “after.” Only Adam the second, to whom time is an all-enveloping personal experience, has to cope with the tragic and paradoxical implied in it.

In the covenantal community man of faith finds deliverance from his isolation in the “now,” for the latter contains both the “before” and the “after.” Every covenantal time experience is both retrospective, reconstructing and reliving the bygone, as well as prospective, anticipating the “about to be.” In retrospect, covenantal man re-experiences the rendezvous with God in which the covenant, as a promise, hope, and vision, originated. In prospect, he beholds the full eschatological realization of this covenant, its promise, hope, and vision. Let us not forget that the covenantal community includes the “He” who addresses Himself to man not only from the “now” dimension but also from the supposedly already vanished past, from the ashes of a dead “before” facticity as well as from the as yet unborn future, for all boundaries establishing “before,” “now,” and “after” disappear when God the Eternal speaks. Within the covenantal community not only contemporary individuals but generations are engaged in a colloquy, and each single experience of time is three-dimensional, manifesting itself in memory, actuality, and anticipatory tension. This experiential triad, translated into moral categories, results in an awesome awareness of responsibility to a great past which handed down the divine imperative to the present generation in trust and confidence and to a mute future expecting this generation to discharge its covenantal duty conscientiously and honorably. The best illustration of such a paradoxical time awareness, which involves the individual in the historic performances of the past and makes him also participate in the dramatic action of an unknown future, can be found in the Judaic masorah community. The latter represents not only a formal succession within the framework of calendaric time but the union of the three grammatical tenses in an all-embracing time experience. The masorah community cuts across the centuries, indeed millennia, of calendaric time and unites those who already played their part, delivered their message, acquired fame, and withdrew from the covenantal stage quietly and humbly with those who have not yet been given the opportunity to appear on the covenantal stage and who wait for their turn in the anonymity of the “about to be.”

Thus, the individual member of the covenantal faith community feels rooted in the past and related to the future. The “before” and the “after” are interwoven in his time experience. He is not a hitchhiker suddenly invited to get into a swiftly traveling vehicle which emerged from nowhere and from which he will be dropped into the abyss of timelessness while the vehicle will rush on into parts unknown, continually taking on new passengers and dropping the old ones. Covenantal man begins to find redemption from insecurity and to feel at home in the continuum of time and responsibility which is experienced by him in its endless totality.* , from everlasting even to everlasting. He is no longer an evanescent being. He is rooted in everlasting time, in eternity itself. And so covenantal man confronts not only a transient contemporary “thou” but countless “thou” generations which advance toward him from all sides and engage him in the great colloquy in which God Himself participates with love and joy.

, from everlasting even to everlasting. He is no longer an evanescent being. He is rooted in everlasting time, in eternity itself. And so covenantal man confronts not only a transient contemporary “thou” but countless “thou” generations which advance toward him from all sides and engage him in the great colloquy in which God Himself participates with love and joy.

This act of revelation does not avail itself of universal speech, objective logical symbols, or metaphors. The message communicated from Adam to Eve certainly consists of words. However, words do not always have to be identified with sound.* It is rather a soundless revelation accomplished in muteness and in the stillness of the covenantal community when God responds to the prayerful outcry of lonely man and agrees to meet him as brother and friend, while man, in turn, assumes the great burden which is the price he pays for his encounter with God.

, from everlasting even to everlasting. He is no longer an evanescent being. He is rooted in everlasting time, in eternity itself. And so covenantal man confronts not only a transient contemporary “thou” but countless “thou” generations which advance toward him from all sides and engage him in the great colloquy in which God Himself participates with love and joy.

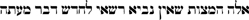

, from everlasting even to everlasting. He is no longer an evanescent being. He is rooted in everlasting time, in eternity itself. And so covenantal man confronts not only a transient contemporary “thou” but countless “thou” generations which advance toward him from all sides and engage him in the great colloquy in which God Himself participates with love and joy. : “And the Lord came down upon Mount Sinai.”

: “And the Lord came down upon Mount Sinai.” : “And the Lord called Moses up to the top of the mount, and Moses went up.”

: “And the Lord called Moses up to the top of the mount, and Moses went up.” .

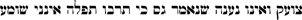

. , the recital of prayers with the congregation, which occupies such a prominent position in the Halakhah.

, the recital of prayers with the congregation, which occupies such a prominent position in the Halakhah. , that no prophet is allowed to change even the smallest detail of the law (Torat Kohanim 120; Temurah 16a; Shabbat 1042; Megillah 3a; Yoma 80a). The adjective “normative” has a dual connotation: first, legislative action; second, exhortatory action. While Moses’ prophecy established a new covenant entailing a new moral code, the prophecies of his followers addressed themselves to the commitment taken on by the covenantal community to realize the covenant in full. Vide Chagigah 10b; Bava Kamma 2b; Niddah 23a; Yesode ha-Torah IX, 1–4.

, that no prophet is allowed to change even the smallest detail of the law (Torat Kohanim 120; Temurah 16a; Shabbat 1042; Megillah 3a; Yoma 80a). The adjective “normative” has a dual connotation: first, legislative action; second, exhortatory action. While Moses’ prophecy established a new covenant entailing a new moral code, the prophecies of his followers addressed themselves to the commitment taken on by the covenantal community to realize the covenant in full. Vide Chagigah 10b; Bava Kamma 2b; Niddah 23a; Yesode ha-Torah IX, 1–4. , that the recitation of Shema with its benedictions be joined to the recital of Tefillah, the “Eighteen Benedictions,” is indicative of this idea. One has no right to appear before the Almighty without accepting previously all the covenantal commitments implied in the three sections of Shema. Vide Berakhot 9b and 29b. Both explanations in Rashi, Berakhot 4b, actually express the same idea. Vide Berakhot 14b and 15a, where it is stated that the reading of Shema and the prayers is an integrated act of accepting the Kingdom of Heaven in the most complete manner. It should nevertheless be pointed out that the awareness required by the Halakhah during the recital of the first verse of Shema and that which accompanies the act of praying (the recital of the first benediction) are related to two different ideas. During the recital of Shema man ideally feels totally committed to God and his awareness is related to a normative end, assigning to man ontological legitimacy and worth as an ethical being whom God charged with a great mission and who is conscious of his freedom either to succeed or to fail in that mission. On the other hand, the awareness which comes with prayer is rooted in man’s experiencing his “creatureliness” (to use a term coined by Rudolf Otto) and the absurdity embedded in his own existence. In contrast to the Shema awareness, the Tefillah awareness negates the legitimacy and worth of human existence. Man, as a slave of God, is completely dependent upon Him. Man enjoys no freedom. “Behold, as the eyes of servants unto the hand of their master, as the eyes of a maiden unto the hand of her mistress, so our eyes look unto the Lord our God until He be gracious unto us.”

, that the recitation of Shema with its benedictions be joined to the recital of Tefillah, the “Eighteen Benedictions,” is indicative of this idea. One has no right to appear before the Almighty without accepting previously all the covenantal commitments implied in the three sections of Shema. Vide Berakhot 9b and 29b. Both explanations in Rashi, Berakhot 4b, actually express the same idea. Vide Berakhot 14b and 15a, where it is stated that the reading of Shema and the prayers is an integrated act of accepting the Kingdom of Heaven in the most complete manner. It should nevertheless be pointed out that the awareness required by the Halakhah during the recital of the first verse of Shema and that which accompanies the act of praying (the recital of the first benediction) are related to two different ideas. During the recital of Shema man ideally feels totally committed to God and his awareness is related to a normative end, assigning to man ontological legitimacy and worth as an ethical being whom God charged with a great mission and who is conscious of his freedom either to succeed or to fail in that mission. On the other hand, the awareness which comes with prayer is rooted in man’s experiencing his “creatureliness” (to use a term coined by Rudolf Otto) and the absurdity embedded in his own existence. In contrast to the Shema awareness, the Tefillah awareness negates the legitimacy and worth of human existence. Man, as a slave of God, is completely dependent upon Him. Man enjoys no freedom. “Behold, as the eyes of servants unto the hand of their master, as the eyes of a maiden unto the hand of her mistress, so our eyes look unto the Lord our God until He be gracious unto us.”

, the unitary acceptance of the Kingdom of God, it refers to the two awarenesses which, notwithstanding their antithetic character, merge into one comprehensive awareness of man who is at the same time the free messenger of God and His captive as well.

, the unitary acceptance of the Kingdom of God, it refers to the two awarenesses which, notwithstanding their antithetic character, merge into one comprehensive awareness of man who is at the same time the free messenger of God and His captive as well. , as an act of acceptance of the Kingdom of Heaven, is discussed in another passage; see Berakhot 21a and Rashi there.

, as an act of acceptance of the Kingdom of Heaven, is discussed in another passage; see Berakhot 21a and Rashi there. , in the emergence of a personal inadequacy. Indeed, in Maimonides’ view, it is not the moral culpability for the sin of murder but the bare fact of being the agent and instrument of murder which causes this disqualification. Hence, the disqualification persists even after the murderer has repented; vide Tefillah, XV, 3, and Tosafot, Menachot 109a. Such a disqualification is inapplicable to prayer. The privilege and right of prayer cannot be denied to anyone, not even to the most wicked. The Psalmist already stated that everyone is admitted to the realm of prayer:

, in the emergence of a personal inadequacy. Indeed, in Maimonides’ view, it is not the moral culpability for the sin of murder but the bare fact of being the agent and instrument of murder which causes this disqualification. Hence, the disqualification persists even after the murderer has repented; vide Tefillah, XV, 3, and Tosafot, Menachot 109a. Such a disqualification is inapplicable to prayer. The privilege and right of prayer cannot be denied to anyone, not even to the most wicked. The Psalmist already stated that everyone is admitted to the realm of prayer:  “O Thou who hearkenest to prayer; unto Thee doth all flesh come.” (Even drunkenness does not disqualify the person, but nullifies the act of prayer because of the lack of kavvanah; see Maimonides, Tefillah 4, 17.) In fact, the Midrash never stated that a sinner has been stripped of the privilege of prayer. It only emphasized that prayer requires a clean heart and that the prayer of a sinful person is imperfect. The Midrash employs the terms

“O Thou who hearkenest to prayer; unto Thee doth all flesh come.” (Even drunkenness does not disqualify the person, but nullifies the act of prayer because of the lack of kavvanah; see Maimonides, Tefillah 4, 17.) In fact, the Midrash never stated that a sinner has been stripped of the privilege of prayer. It only emphasized that prayer requires a clean heart and that the prayer of a sinful person is imperfect. The Midrash employs the terms  and

and  , which denote pure and impure prayer. Maimonides quoted the Midrash not in the section on Tefillah, which deals with the Halakhic requirements of prayer, but in that of Teshuvah, which deals with the metaphysical as well as the Halakhic aspects of repentance, where he says distinctly that the immoral person’s prayer is not fully acceptable to God—

, which denote pure and impure prayer. Maimonides quoted the Midrash not in the section on Tefillah, which deals with the Halakhic requirements of prayer, but in that of Teshuvah, which deals with the metaphysical as well as the Halakhic aspects of repentance, where he says distinctly that the immoral person’s prayer is not fully acceptable to God— “He petitions and is not answered, as it is written, ‘Yea, even ye make many prayers I will not hear.’” As a matter of fact, Maimonides extended the requirement for moral excellence to all mitzvah performances—

“He petitions and is not answered, as it is written, ‘Yea, even ye make many prayers I will not hear.’” As a matter of fact, Maimonides extended the requirement for moral excellence to all mitzvah performances—

“He performs mitzvot and they are thrown back in his face.” It is of course self-evident that the imperfection inherent in the deed does not completely nullify the objective worth of the deed. Maimonides’ statement at the end of Tefillah “that you do not prevent the wicked person from doing a good deed” is not only Halakhically but also psychologically relevant. We let the sinful priest, as long as he has not committed murder or apostasy, impart his blessings to the congregation. Likewise, we encourage the sinner to pray even though he is not ready yet for repentance and moral regeneration, because any mitzvah performance, be it prayer, be it another moral act, has a cleansing effect upon the doer and may influence his life and bring about a complete change in his personality. Vide also, Introduction to Beth Halevi on Genesis and Exodus.

“He performs mitzvot and they are thrown back in his face.” It is of course self-evident that the imperfection inherent in the deed does not completely nullify the objective worth of the deed. Maimonides’ statement at the end of Tefillah “that you do not prevent the wicked person from doing a good deed” is not only Halakhically but also psychologically relevant. We let the sinful priest, as long as he has not committed murder or apostasy, impart his blessings to the congregation. Likewise, we encourage the sinner to pray even though he is not ready yet for repentance and moral regeneration, because any mitzvah performance, be it prayer, be it another moral act, has a cleansing effect upon the doer and may influence his life and bring about a complete change in his personality. Vide also, Introduction to Beth Halevi on Genesis and Exodus. in Hebrew means both to say and to think.

in Hebrew means both to say and to think.