Schools are a special situation in permaculture design. No-one lives there, students grow up and leave each year, there is no permanent ownership of the garden area, no-one looks after it all of the time, and much of what we put in may be cosmetic and for demonstration.

However, what better place is there to become partners with nature and to learn about the water cycle, nutrient cycles, earthworms, food chains, soil and foods than a school garden? Teachers do not have to take class.mapes long distances to observe nature. They can create gardens and bush or mini-forest areas right at the school.

Gardening allows teachers to instil a love for nature and for the land, and if students feel intimately involved with nature, their concern for environmental problems will be long-lasting. Some of the positive outcomes from building gardens are the sense of pride and accomplishment in meeting success, and feelings of self-worth as things start to grow and change occurs.

Even so, it is difficult to grow heaps of vegetables because other students, vandals and community members may raid the garden and destroy or steal things. Chickens can disappear after a weekend, ponds may be spiked and then leak, and plants are uprooted and thrown about the place. This doesn’t happen all of the time or at all schools. But it does occasionally happen and teachers and designers need to be aware of this. In other words, schools have different needs that must be considered in the design process.

In working with children and schools, as with any permaculture client, you need to determine:

• the needs and wants of the children, teachers and the school.

• what the budget is (how much can they spend).

• how much time and energy is available to implement, maintain and develop the garden area.

• what resources are available -both on site and in the local community.

• the potential site - its limitations, existing structures and positive qualities.

The biggest stumbling block for the development of school grounds is money. Usually the school administration and staff are on-side but lack of resources often dampens the enthusiasm. Materials can be obtained from a variety of sources, such as donations from the local nurseries and landscape suppliers, but often you have to beg students, parents and staff for plants, pond materials and other donations. Accessing resources and materials is an ongoing project, and this needs to be considered in the initial designing stages.

To determine the needs of a school, the budget and level of support in the community, you really need to discuss your ideas with a wide number of people, some of whom will include the teachers who want to use the area, school principal, other school staff, the gardener, and members of the school council and/or the parents and citizens (or parents and friends) association.

The resources available should be assessed. Does the school dump its lawn clippings or are they composted on site? Is there money for plants, mulch and compost? How much land is available? Is a source of water and irrigation near the proposed area? Ask yourself these types of questions.

Resources can take the form of people, materials, money and energy. Material resources can be assessed, for example, by getting students to conduct surveys which determine the amount of building supplies, newspapers, carpet or underfelt, tyres, sleepers and bricks which the school can obtain from the local community -either by way of donation or, at least, at reduced cost.

Securing “people resources” should be a high priority. Staff training and professional development are crucial to the success of a school garden area.

Individual teachers don’t have time to spend maintaining the garden, so this responsibility should be shared.

It is best if all staff could have some training in permaculture, but this may not be possible. At the very least, the school should make a financial and supportive commitment to make sure several staff have an active interest in the garden.

Having a school gardener who is sympathetic to permaculture ideas is an added bonus for any school. However, schools which do not have a regular gardener, or which rely on community or parent support to maintain the school lawns and garden areas, should not be seen as disadvantaged.

There are many parents and community members, not directly associated with a particular school, who jump at a chance to put in gardens and gain practical experience after they have done a permaculture course. Some of these may be working towards their Permaculture Diploma and are more than willing to devote some regular time and energy to the school grounds.

Guidelines for designing school grounds

Involve children as much as you can. Teach them about design. Get them to measure the area and do scale drawings.

Show them how to build sheet mulch garden beds, visit established local permaculture properties and discuss the main principles and concepts of permaculture. Many students will begin to understand the ideas after they can visualise what they can do at their school. Students learn by seeing and then doing.

It may not be possible for the students to come up with a fully-functioning design, but unless they have some ownership, along with the teacher, of the plan, the future success of the garden area is not guaranteed. Children get excited and willing to work when they know that what they are doing is something they have contributed to. You may be surprised at the number of really good (and innovative) suggestions they make about the garden and site development. Lead them gently through the process.

Your role, as a designer, is to oversee the development and offer expertise and help. It should not be your job to draw the design without input from the “users”. Keeping this in mind, here are some useful guidelines when considering building gardens in schools:

• consider the ages of the children. Small areas are great for small children, not so good for teenagers. Garden beds may have to be smaller than usual so that children can access all areas easily.

• children like their own garden beds. Groups of two or three work well together and can easily build, plant and look after their beds. Individuals should be allowed to develop their own garden if they ask, but encourage group co-operation. Remember that we are trying to teach life skills and community values, as well as gardening.

• sometimes different class.mapes want a part of the garden. It may be better to consider building small garden areas nearby each class.maproom, rather than one larger area away from the school. Smaller gardens, solely the responsibility of one class.map and one teacher, are more intimate for the children. Alternatively, allocate different areas in the larger garden for those class.mapes and teachers that do want their own space.

Figure 12.1 Small, easy-to-build and maintain garden beds should be developed by different groups of students.

• will other groups of people, besides those directly building and maintaining the garden, be using the area? How can you use other teachers and their class.mapes in the garden? Can you ask the art department to get their students to design and make clay-fired bird-baths? Do they want to display some of their sculptures in the garden? Will manual arts help build the seats you want to put in the area? Do any science teachers want to set up and stock a pond? If you involve everyone, then everyone will own the garden.

• will the produce from the garden be sold, taken home or given away? Is the school canteen willing to buy foodstuffs from the students? What kinds of foods would the canteen want? Gardening gives a direct connection to our food source. Many students initially fail to see the connection of what they are growing to the food they eat at home.

• some garden beds could contain plants for propagation work. These stock garden beds may be small beds of particular herbs that are used for cuttings and grafting work. Beds could have different themes. For example, one bed for culinary herbs, another for medicinal herbs and another for pest repellent herbs. All students could then take small pieces of these plants from the stock beds for their own use.

• outside activities should be organised and related to the curriculum. Many educational objectives and outcomes can be covered by simple, fun-to-do activities in your new outside class.maproom.

• other types of activities lend themselves to schools. For example, nesting boxes for birds, possums and bats could be studied by science students. Place one or two bird baths and/or feeding trays in the garden - you’ll be surprised what you will attract. Build a weather station that holds equipment which measures daily temperature and barometer changes, humidity, rainfall and wind direction and speed.

Figure 12.2 Bird boxes and bird baths in the school grounds are useful teaching aids.

• an energy audit of the school buildings would provide information about electricity consumption and waste in the class.maprooms. This could lead to the development of an energy management policy and a desire to reduce school operational costs.

At all times we are trying to teach young people about the six R’s -reduce, refuse, reuse, recycle, repair and rethink.

• as schools move more into environmental education other school-directed activities follow. For example, the school may become the recycling centre for the local community.

Glass, paper, metals and plastic are brought in by students or their parents, maybe once a week. Money raised from this venture is invested back into the school to provide equipment and teaching resources.

• in some circumstances the school garden could become the community garden. Parents and community members could help students with garden development and/or be responsible for areas themselves. They may grow things to take home or for use by the school.

There is a general push by governments and education authorities to better use schools as this valuable resource is under-utilised at present.

Community gardens are one way to ensure a win-win situation. It also helps alleviate some of the potential vandal problems mentioned earlier.

One of the pleasing outcomes is that students start to teach their parents. Children soon build ponds and gardens at home, plant vegetables and develop simple earthworm farms and compost heaps after they see how easily it is done at school. The skills that children learn help build their self-esteem as they realise that they have the ability to grow things and that they have a role to play as part of a co-operative team - a role that they learn at school which they continue to develop throughout their life as part of the local community.

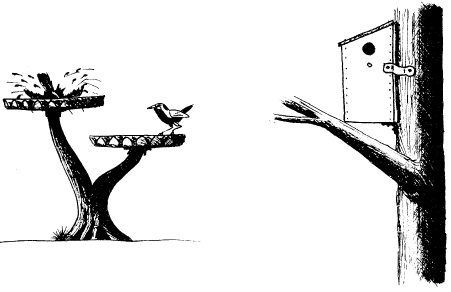

Figure 12.3 Bush tucker and bush medicine plants make useful additions to any garden.

Practical design considerations

The development of the school grounds should be within the parameters of the school plan or the vision for the future direction of the school. For example, if the school wants to conserve water and plant a native garden, then consider native bush tucker and bush medicine plants. Many schools already have a master grounds plan. A permaculture design of one particular area needs to complement any existing school plans.

If natural bushland or woodland is on the school site, develop a strategy to replant, maintain and protect this area. Part of your design for the school should address this issue. You may be able to develop a walk or nature trail, register the bushland as a heritage value area, or seek state or local government assistance to help preserve the area from overuse.

The number of activities, garden ideas and design strategies are endless. Teachers and students will be able to experiment and see what works best for them and their school environment and situation. However, here are a few ideas and practical considerations that have worked well in schools:

• where will tools such as shovels, pitch forks, hand trowels, gloves and wheelbarrows be stored? What about potting mix, plant pots, watering cans and seeds?

Can you put a lockable shed in the design so that all of these are available on site? Worry about buying or obtaining one later on.

• plan for open space. You have to get at least one class.map in the garden area at any one time. This could be up to thirty students - where are you going to put them all?

Consider bench seats and areas of herb lawn where students can sit and work. Not everybody has to work on the garden beds during the lesson. Some will want to plan, record, draw and think.

• main pathways have to be wide. It is not practical to have the half-a-metre path that you have at home in the school garden area. Plan for a couple of students walking side-by-side or wide enough for a wheelbarrow and some leeway so accidents don’t happen.

A pathway about 1.2 m wide is ample for school gardens. Smaller pathways are more suitable for individual (student) garden areas, or to lead to quiet places within the garden.

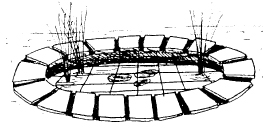

The typical size of a Mandala keyhole garden is not appropriate in some schools. You either have to make the paths and keyholes larger or consider making a double Mandala with keyhole beds on the outside as well.

• secret or quiet places are important. Children like to hide, especially from teachers, and secret garden areas provide sanctuary. Young children are quite happy to play hide and seek, older children hide for different reasons, so teachers should not make secret places too secret or overgrown.

It is possible to include areas for student privacy, yet still make these visible from the staffroom or class.maproom.

• seating is essential. Simple log or bench seats are more than satisfactory, but rock or carved seats can really look great.

Older students do like to sit and talk. Younger students are too busy running around.

• plan for some garden areas to be shaded. This could mean placing some of the seats under large trees or using structures like walkways, vines and pergolas.

In hot climates, shade from the sun is a critical factor in design, as students will only use and sit in the garden area if they feel comfortable.

Figure 12.4 Two different ideas for a double Mandala which provides greater student access to the garden beds.

Many schools have policies about outside activities and the precautions needed to be taken by students, including wearing hats and sunscreen cream, and the length of exposure time in the sun. There are great opportunities to design areas for shade so that students can safely work in the garden.

Figure 12.5 Students value a quiet place to sit and talk.

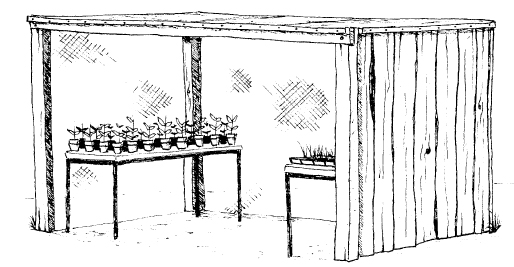

• developing your own shrub and tree nursery will help in reducing costs of obtaining plant stock for the garden. This can be as simple as a potting area, small shade-house (covered frame) or a series of benches in a hothouse for plant propagation.

Figure 12.6 A simple nursery can be set up to raise seedlings for your garden beds.

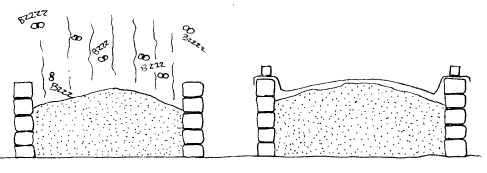

• compost areas may cause some minor problems. Freshly-made compost tends to smell, especially when you use animal manures and it is summer! If there is a likelihood that odours may occur near class.maprooms, consider shifting the compost area to another part of the school away from buildings. This may not sound the best strategy from a permaculture viewpoint, but you have to consider the needs and comfort of teachers and students.

Figure 12.7 Compost may smell if it is not covered up.

Open, uncovered compost and manure piles could attract flies and pests. It is worth while to build proper storage bays from wooden sleepers or concrete slabs so that these can be easily covered with hessian, carpet or underfelt to reduce the smell and pest problem while the compost is being made. While the end product may have a “nice earthy smell” the process of decomposition produces a range of noxious gases if the ratio of plant and animal materials, water and oxygen are not right.

Figure 12.8 Ponds may need to be covered to protect young children. Alternatively, consider a bog garden which will not need the mesh covering.

• there are often some restrictions on building ponds in school grounds. Some education departments or authorities have rules and regulations, mainly for safety reasons, about water areas. Find out what these are. Your pond may have to have a weld mesh cover over it, or only a certain depth or a certain size.

Schools should be fun! Developing an outside class.maproom, where students can both learn and enjoy, is a sensible way in which educators can effectively teach the “curriculum”.

Some students only seem to learn by working outside in the garden or doing practical activities. Others thrive in the more academic sphere. All students, however, need stimulating lessons to hold their interest. What better way is there than to go outside and observe and learn from nature?