Bill Mollison, in his Designers’ Manual, states that permaculture design “is a system of assembling conceptual, material and strategic components in a pattern which functions to benefit life in all of its forms.”

Moreover, the human intellect needed in the design process distinguishes permaculture from conventional landscape practices and it is human imagination that is the key to permaculture design. We are only limited by our own imagination and life experience.

The best designers are those who have a wealth of practical experience. They know what works and what doesn’t. They know which plant and animal guilds work well for that area and climate (see Chapter 6) and they are realistic in their expectations about implementing the design.

Grandiose designs, which are totally inappropriate or expensive, are not in the best interests of all concerned.

The fundamentals of permaculture design have arisen from an understanding of the cycling of matter and energy in nature. Here, matter and energy are passed from organism to organism along various food chains. Organisms die and decay, and their wastes are also broken down, which releases stored nutrients to the soil. These nutrients can then be reused by plants to continue the cycle of life and death.

Figure 4.1 Matter and energy flow and cycle within an ecosystem.

Furthermore, permaculture designs are based on broad, universal principles which allow for local knowledge so that local species can be incorporated. This makes sense. Wherever possible, local resources and species, found in that soil type, climate and area, should be used. This is both economically and ecologically responsible action.

In designing, we repackage or re-assemble components already existing on the property and incorporate new ones. Components are assembled and elements placed according to the function they perform. We use insight to develop unique and effective strategies. The design may examine many options and some decisions of particular options are taken so that they are definitely included.

Each permaculture design is tailor-made. It is the marrying and blending of what grows best in the particular area and soil with what the owner or gardener wants. Permaculture empowers people to solve their own design problems and apply solutions to their everyday situations. Designers have a responsibility to recognise which permaculture principles need to be applied to a specific problem or situation. Solutions may include the use of edge, patterns or guilds, and good designers see every difficulty as really an opportunity.

For any design to be useful it must have ownership by those living on the land. A design should involve everyone who lives there. A design is a collaborative effort, rather than the result of an “expert designer”.

The trees are planted by the property owners and cared for by them to ultimately benefit themselves. The emphasis here is people. This is why participation in the planning and design is crucial to its success. Designing is a consultative process involving all of those living on the property and, sometimes, various advisers.

You can’t successfully impose your ideas about a design on someone else’s property. You have to work alongside the owners, so that they feel they have made a worthwhile contribution and they feel that they have ownership. In effect, we should teach people how to plan rather than plan for them.

Permaculture designing, then, is actively planning where elements are placed so that they serve at least three functions. We have already talked about how nothing is wasted in a permaculture system. The system we design also needs to use all of the outputs or products.

Pollution occurs when a system has excess outputs. The wastes of one element are used as the needs of another. The manure from the chickens helps the compost heap.

Dead leaves and fallen fruit keep the earthworm farm going, so that the castings produced will be the fertiliser or potting mix for your garden plants. If any product is not used, we have a potential pollutant and this is unacceptable in a permaculture system. Remember, we don’t have liabilities, only assets.

Figure 4.2 Elements serve at least three functions (earthworm).

A permaculture design is more than just a landscape plan. Maps, plans and overlays do not indicate or suggest the interconnectedness between things, nor can they deal with other aspects of permaculture such as the social and financial aspects of human settlements. However, a landscape-style plan does give some indication about dam and house placement, and the future location of swales and orchards.

You might think about the design as being a visual representation of the concept. Implicit in any design should be a number of energy harvesting and modifying strategies, a number of soil, water and land conservation strategies, a number of food producing strategies and a number of human settlement strategies, such as housing, shelter, village development and so on.

Designs always change and hopefully for the better. The design is the beginning point of the journey, and as new ideas and experiences develop, the design evolves as well.

While the client’s wishes for a site are important, foremost is the consideration of the site itself.

What you are really doing is working out how the property will improve and become rehabilitated, because clients sell properties and move on. Look beyond the client and see the land.

When designing, all things that could affect the land should be considered. This includes sewage treatment, water storage, food production areas, placement of animals and the needs of humans. For example, you need to consider the characteristics of each tree you plant, such as spread or width, height, and whether evergreen or deciduous.

It may seem silly to plant a carob fifteen metres away from all other trees, but if you’ve seen a mature carob, you’ll understand that they are often much wider than their vertical height.

There are some things on a property that you can easily change when you are working on a design and there are some things that you can’t change. For example, you have very little control over the climate in a particular region, whereas you can change roads, location of dams and trees, and construction of fences.

Fences, by way of illustration, can be placed on contours and also along regions of soil change. Fences could then mark where sand areas change into clay areas and so on.

However, keep in mind that this may not be the best solution for a particular property. For example, keyline cultivation, discussed in Chapter 9, places soil type as a low planning priority, so fences may not need shifting.

Many things will affect the development and progression of a property. Some of these are beneficial and some are not. A list of these design considerations might include:

• erosion and salt scalds. Does water cascade over the surface or seep into the ground? What kinds of plants will grow in soil areas of high salt content?

• prevailing wind directions. Where will windbreaks be placed?

• views - those you want and those you want to hide. Where will you plant screen trees to give yourselves privacy?

• sources of noise and pollution, such as busy roads. Use trees to screen and to absorb pollutants from vehicles.

Permaculturists have to become accountable and ask themselves the questions “Do I create waste? Do I consume vast amounts of energy, electricity and heat in the home or vehicles?”

Figure 4.3 We have a responsibility to minimise our impact in the environment.

• recharge and discharge areas. Where does water enter the landscape and where does it re-surface?

• waterlogging and soaks. Are there areas that are permanently damp, clayey or waterlogged?

• slope of the land. Contours should be determined as water harvesting and water movement control are essential in dry climates.

• other components of the environment, such as aspect, amount of vegetation cover and soil type.

Our environment doesn’t necessarily just mean the biological and non-biological components in the scientific sense, because, when we consider humans we also have to consider the economic, social and cultural aspects.

Furthermore, natural vegetation has intrinsic value and needs protection.

• amount of resource material available on site. Start by looking at the resources you already have or have access to. These vary from sources of mulch to clay and stone for building materials.

People argue that we ought to recycle more of the items we use daily, but I think that waste minimisation is a better, sounder path to tread.

It makes sense to use less than to recycle more. People often talk about “reduce, reuse and recycle”. I would like to add “repair, refuse, re-think, re-assess, refrain, reject and reconsider”.

Resources can be skills as well as materials. You need to establish what the client/s can do as part of the overall plan for the property.

You must also consider the needs of all occupants of a property, including children. Do children eat the same food as adults? Or is my family different from everyone else’s? All need to be involved in the decision-making. However, making choices always involves consequences, compromises and trade-offs.

The process of designing can be seen as a series of steps or phases. Like all planning exercises there is an order to follow when these things are undertaken. These steps are discussed in turn, but a brief overview would be:

1. Information phase - observing and collecting data.

2. Analysis phase - reflecting, examining and collating data. Recognising patterns.

3. Design phase - determining strategies, re-organising and placing elements in the system. Zoning and sector planning.

4. Management phase - implementing, priorities for implementing, and monitoring and maintaining.

This is when you collect information about the site. Data can be collected through observation, or by examining maps and records, and by discussion with the property owners (and occasionally their neighbours).

It is essential to consider the needs and desires of the people living on the property and involve them as much as possible in the early stages of the design process. This can be as simple as getting them to list the resources available on the property or to write down their observations about storm and winter winds, flooding areas and so on. Good listening, to both land and people, is a hallmark of a good designer.

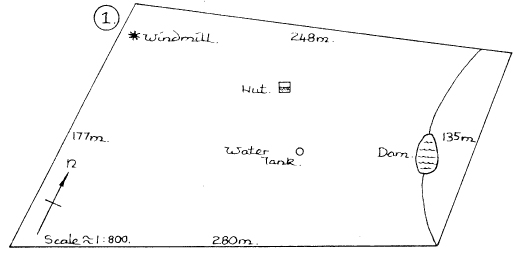

The most important information you need for a design is a map of the property. A scaled diagram showing the dimensions of each boundary and present location of the house, outbuildings and other structures, is used for the basis of the design. Maps are very useful tools. You can obtain maps from local or state authorities which show the contours on a property (although these are not often accurate) and property shape and sizes.

The next requirement before the design actually begins is to mark and draw the existing landscape features - contours, ridges, valleys, streams and watercourses, rock outcrops and soil types, and including the location of the proposed house and outbuildings.

Contour lines on the map will determine where dams and water harvesting or movement will, or can, occur. Contours on the slope will also determine where retaining walls may need to be built and where particular garden beds or orchard areas should be placed. Using graph paper for your map is very useful and allows you to draw structures and ideas in proportion and to scale.

Figure 4.4 A map of the property is the first step in the design process.

It is often useful to do nothing to your property for a year or so. At least see what happens during each season, such as which weeds flourish (as an indication of soil conditions), where the frost line is in the lower parts of the block and which are the prevailing wind directions.

Figure 4.5 Develop the map by locating and drawing contours, landforms and other structures.

Detailed and careful observation must be made of such things as wind directions, water movement on the property, amount (degree) of slope, sun angles during summer and winter, moist and wet areas, shady and sunny areas, changes in soil type, and natural patterns in any prominent land formations.

Information about rainfall, insolation days and seasonal wind direction and speed, can be obtained from sources such as the Bureau of Meteorology and, in some cases, the local post office or local government authority.

You should establish if you have the client’s permission to spend money, on their behalf, for aerial photographs or cadastral and topographical maps, resource booklets of soils and plants of the area and so on.

The analysis phase involves selecting and analysing the proposed elements in the system. A needs analysis may have to be performed on particular elements so that you can make decisions on which elements are best suited in the design.

Figure 4.6 Collecting data and information about the site is a prerequisite to design.

Here we start to also consider zonation and sector planning. We draw and note the sectors for problem areas, such as permanent waterlogging, occasional flood-prone areas and salt scalds. We also identify and mark storm and prevailing wind directions, fire danger directions and sun angles for the property.

Figure 4.7 Draw the zoning and sector planning considerations on your map.

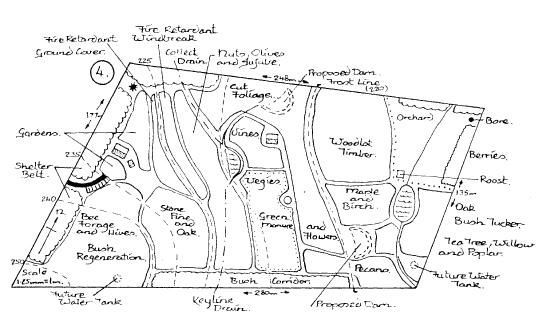

Most often a design is a map or plan which shows the placement of elements or components. This plan is usually a two-dimensional drawing, although a three-dimensional model, while taking a longer time to build and more resources to make, has many advantages. For example, a scale 3D model will allow you to investigate the effect of plant placement on such things as shadows and wind movements.

When drawing the design you can either use a series of overlays or several copies of the basic block plan showing dimensions, contours, natural rock formations, dams and other things which are fixed and mostly cannot be changed.

Some overlays can be used to show future developments, such as the location of new dams, fencelines, additional buildings, general plantings, windbreaks, and commercial enterprises.

Practical aids to help with design work include drawing concepts and garden areas on graph paper, using clay, plasticine, and wooden blocks to place structures in the design, and using a sand pit to shape slope, swales and dams.

All of these aids help us better visualise the design strategies, as seeing a design in three dimensions (3D), as we have just mentioned, is much better than in 2D.

A permaculture design might contain a large amount of information and either show or allow you to:

• identify food production areas, including zone 1 and 2 plantings, orchards and woodlots.

• indicate proposed drainage lines, swales and dams.

This is essential for the control of water movement and harvesting, and to prevent flooding.

• indicate proposed revegetation areas - of natural bush.

Zone 5 is allocated to the conservation and restoration of indigenous plant species.

Figure 4.8 Developing a total design for Ian and Peter’s property in Toodyay, WA.

• recognise the importance of sanctuary. People need to have some place they like to go and visit.

This might be an aesthetic view or somewhere that has a particular calming feel about it. A design might include seats, a gazebo or log to sit on in this area.

• location and position of roads, paths and parking. Access roads should slowly wind upwards towards the house.

Roads leading down to the house site generally cause heaps of problems, including water from rainfall and melting snow cascading toward the house.

Having a driveway sloping away from the house will permit excess water to be diverted to garden and orchard areas (as well as allowing you to jump-start the car when the battery is flat).

• place sheds and house close to water and electricity supplies. This will minimise the costs of installation for these services.

The report, accompanying the design, will list the materials, components, strategies and priorities.

Design reports need ideas and hints about management, and land owners should be encouraged to undertake a permaculture design course so that they can understand the processes which occur and be able to make appropriate decisions about courses of action.

If you are producing a design for someone else, the information that you supply in your design and report must save the property owners much more than the fee you charge.

However, most designs for properties are done by the owners themselves. Few people are professional consultants and designers. A design report for a property typically contains the following information:

• design considerations. Write a brief appraisal of the kinds of things that need consideration in the design.

This includes water availability and quality, the effect of native, feral and domestic animals on garden areas, seasonal climatic changes, landscape, client requirements for the property, orientation of the block and so on.

Figure 4.9 Access roads should rise toward the house.

• site analysis - listing rainfall, temperature extremes and other aspects of the climate, soil type/s, existing vegetation, topography (for example, granite rock outcrops, slope of land and location of water courses) and general overview of the property.

• recommendations. A detailed list of changes to various parts of the property are given.

You might choose broad headings such as south side of block, north side, house site, orchard area, woodlot, zone 5, eastern hill slope and summer grazing area.

Explain and elaborate on these recommendations, including listing things that do not need to be changed on the property.

You need to explain why you are making certain recommendations.

It may not be obvious to the client why you want certain plants grouped together, but if you say that this grouping will be mutually beneficial to each plant and there would be less risk of disease, then the client begins to understand the importance of design.

• priorities. You should list, in order of priority, the sequence to implement the design.

Identify the essential stages, such as water harvesting, which must occur early in the implementation process, and continue to list other important steps to the least important one.

• estimated costs for various stages of development.

• plant list. This contains details of suitable species appropriate for that climate and soil type. It should not list illegal or hard-to-get species.

• background information. Depending on client knowledge, you might include some information about ecological and permacultural principles, such as guilds, stacking and succession.

• strategies for dealing with, or generating, income. Perhaps the client has little financial resources, but may have time and skills.

An early, small income from activities on the site, such as seed collection and plant production, could be designed in.

The client may be in full-time employment off the site and wants to reduce that. Can you plan to move them towards part-time work with an on-site income?

Is there an opportunity for co-operative work in the local community? What does the client have to offer in exchange?

• maintenance of property. This includes information about the ongoing care needed for plants and animals.

You may mention the particular nitrogen-fixing acacias (wattles) that you have included in the design (which will live for only eight to ten years and thus may have to be replaced); when they should add manure or mulch to growing plants; or how they can organically deal with fruit fly or other pests; how vegetables are to be replaced once they are harvested; and what types of husbandry goats or sheep need.

• resources. What resources does the local community offer? This includes people, who have particular expertise, such as dam building or knowledge of soil conditioning strategies, and nurseries where plants can be obtained.

You can also list free sources of mulch, building materials or compost. Recommended reading and references can be included.

Ongoing monitoring and review are essential, as unexpected impacts on soil fertility, plant and animal health and water quality can be noticed and design modifications made. It is important to develop a management plan which is reviewed and changed as the need arises.

There are many ways to monitor changes that occur on the property. This can involve periodically taking a series of photographs or transparencies (slides) which will depict growth and change in trees, and general development. Records of acidity (pH) and salinity levels in soils, dams, bores and other waterways can be kept and examined for trends. The data you collect from these types of activities will enable you to adjust the design strategies for these particular areas.

This phase also includes design implementation or execution which is covered next.

Building gardens costs money. Too often we try to do too much too soon. We run out of energy, enthusiasm and money, and then time, to maintain the garden. Start off small, and when a particular area is set up, then move on and develop and build more gardens.

Work within your budget and plan to take a few years to implement your design. Start slowly from your house - work outwards from one zone to another.

Cost out each step or you may be disappointed and frustrated that you cannot complete the project because you have run out of funds. This idea of starting small and slowly progressing cannot be over-emphasised.

The implementation timescale should be based on economic reality - what you or the client can afford to do as time passes. Don’t be too ambitious. Start small and meet with success. Then slowly expand as more resources, such as time, materials, money and energy, become available.

The order is: look after what we have first, restore what we can next and then finally introduce new elements into the system. When establishing a property the following are the sorts of things you need to do, not necessarily in the order of priority:

• water supply - earthworks, dams, swales, roads and drains. Priorities include the development of good water and appropriate earthworks such as drainage, dams and the foundations for the house.

Earthworks are generally costly. There is a high cost for any sort of machinery and an operator, so plan to do as many jobs on one day as you can.

For example, dig the power line to the shed and holes for a small pond or dam, level the ground for driveways, clear fallen trees, dig drainage lines to move water and so on.

• access roads and paths.

• structures - shelter. While machinery is available for earthworks do the house and shed pads.

• shelterbelts and windbreaks for gardens, orchards and planted areas.

• energy-producing or harvesting structures.

• plant procurement - nurseries, seed collecting and germination. You may need literally thousands of plants per hectare.

Implementing a design, even in a small backyard, can be daunting for some people. A lot of human-hours and human energy has to be expended to just build a few gardens.

This is where friends can be handy. Working with other people has many benefits and more can be accomplished while working as a team.

You sometimes hear of the term “synergy” when groups of people work together. This is where the sum of the whole is greater than the sum of the individual parts.

In other words, only a certain amount can be done by yourself, whereas working with someone else accomplishes more than two individual efforts. In essence, one plus one equals three.

There is a greater sense of satisfaction when you share the journey with others and the actions of many people can inspire you to continue to grow.

Remember, designers do not have to be experts on building houses and dams, identifying plants and animals, or driving heavy machinery.

A designer only has to examine the interrelationships between things and see possibilities to promote both biodiversity and productivity.