Figure 1

Charles W. Mills

Following Carole Pateman, I too now turn to the crucial question of race/gender intersection, of when and where (or if and how) women of color enter the social contract universe.

In 1886, Anna Julia Cooper announced: “Only the BLACK WOMAN can say ‘when and where I enter . . . then and there the whole Negro race enters with me’” (1998: 63). This proclamation has long been a trumpet call for black American women, providing the title of Paula Giddings’s pioneering black feminist text, When and Where I Enter (1984), and inspiring other feminists of color increasingly insistent over the last two to three decades that neither white feminism nor nonwhite male antiracism can speak adequately for them. So if the original challenge to a bogus universalism was “What do you mean we, white man?” the more recent variants have become “What do you mean we, white woman?” and, more recently still, “What do you mean we,black man?” A book jointly written by two of these new (non-usual) suspects, a white woman and a black man, must therefore be particularly self-conscious about not simply reproducing such past exclusions, especially given that Pateman’s original “sexual contract” had little to say about race while my “racial contract” had little to say about gender. Indeed, taken together they might seem perfectly to exemplify the indictment of another classic 1980s text of black feminism, All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, But Some of Us Are Brave (Hull et al. 1982). As Laura Brace comments, perhaps a bit unkindly:

The racial and sexual contracts are difficult to put together because they stand rather stiffly beside one another without ever really engaging. . . . They work together Pateman and Mills, they do a double act on the conference circuit, 1 and they’re writing a book together called The Domination Contract,but she does gender and he does race. I suspect that it’s partly using the social contract as their explanatory device that allows them to carry on dis-engaging like that. (2004: 3)

So the obvious question is whether an engagement – and indeed a marriage – can be arranged between these stiff and distant parties, or whether the contract framework itself inhibits any such matrimonial get-together (or would make it, perhaps, no more than a marriage of convenience, never to be consummated). In the previous chapter, Pateman gave her political scientist’s reply to this question; here I will offer my more abstract philosophical one.

Why bother, though? If it’s difficult enough to think race and gender together (let alone in combination with other factors), as the huge and ever multiplying literature on “difference” and “intersectionality” shows, why exacerbate these problems by trying to formulate them within the somewhat awkward and artificial additional framework of a “contract”? Obviously, the claim – the hope – has to be that the theoretical payoff will make it worthwhile. Political philosophy has been spectacularly revived over the last three decades, generating a vast out-pouring of articles, books, series, introductory texts, and reference companions. But a vanishingly small proportion of this material addresses the distinctive problems of women of color. There is, in fact, an almost complete disconnection between two huge bodies of literature, the writings on race/class/gender intersectionality in feminism, sociology, history, legal theory, cultural studies, and so forth, on the one hand, and the writings on social justice in philosophy on the other. A highly regarded black feminist text of ten years ago like Dorothy Roberts’s 1997 Killing the Black Body,which seeks to “confront racial injustice in America” by tackling the “assault on Black women’s procreative freedom” (Roberts 1999: 4), will not through the most powerful Hubble telescope appear in the universe of discourse of the Rawlsian secondary literature. These are in effect two parallel non-intersecting universes. But wasn’t the original point of resurrecting contract theory to adjudicate what would be a just social order? Wasn’t the point of starting with ideal theory to be able to eventually move on, better equipped, to non-ideal theory? Yet the response of most white male political philosophers to the growing irrelevance of their apparatus to the real world (and the concerns of the majority of the population) seems to be not, as it should be, “So much the worse for this apparatus,” but, remarkably, “So much the worse for the real world (and the concerns of the majority of the population).”

The point of the project, then, is to contribute toward ending this ludicrous situation by helping to create a possible theoretical space, an opening in this area of philosophy, for women of color interested in the field – and, for that matter, for all ethicists interested in making their prescriptions truly general. (It is not, of course, that social justice issues have to be discussed in a contract framework. But given the continuing hegemony of Rawlsian approaches, a conceptual intervention here is likely to have more impact than elsewhere.) At present, by contrast, as Naomi Zack points out in the introduction to her edited volume Women of Color and Philosophy, the overwhelming demographic whiteness of the profession and the hostile conceptual terrain interact in a disastrous positive feedback loop to repel nonwhite women in particular. They are likely to be seen “as having doubly benefited from affirmative action hiring policies,” to have “scholarly interests [that] are marginal in the field,” and thus to be multiply “atypical” figures as philosophers, with at least “initial failures of credibility with colleagues, as well as students” (2000: 7).

In the introduction to The Racial Contract, written a decade ago, I commented on the paucity of African-American philosophers in the profession, only about 1 percent of the North American total (Mills 1997: 2). In the ten years since then, that figure has not changed, proportionally. What I did not single out for special mention, and perhaps should have, is how few of these were women. Even today, there are not more than thirty or so black women in philosophy. And black women, pathetic as their numbers are, actually represent the largest nonwhite female group. The figures for Latina and Asian-American philosophers are even lower (moreover, some Latinas self-identify as racially white), while with Native Americans, it’s not more than five or six people in the entire United States. All nonwhite female philosophers put together constitute perhaps half of one percent of the North American total.2

So if women of color have emerged as a global force, as Cherríe Moraga, the co-editor of This Bridge Called My Back, one of the most famous women of color anthologies, boasts in her foreword to the latest edition (Moraga and Anzaldúa 2002: xvi), they barely make up a block committee in the white male world of professional philosophy. In Nirmal Puwar’s striking phrase, they are “space invaders,” “trespassers” marked by both race and gender as doubly “out of place” in a discipline whose pretensions are paradigmatically to the universal, the world of disem-bodied mind – and which for that very reason cannot accommodate those whose “dissonant bodies” putatively link them so ineluctably to the particular, the physical, the non-universal, the non-representative: “the exclusionary some body in the no body of [philosophical] theory that proclaims to include every body” (2004: 8, 11, 57, 141). Indeed, it is noteworthy that the most famous woman of color with a philosophy background, Angela Davis, does not teach in a philosophy department, or generally publish in philosophy journals, though her book Women, Race, and Class (1981) is one of the pioneering texts in the “intersectionality” literature.

Uma Narayan recounts the experience she, an Asian American, and an African-American woman had at a meeting of the American Philosophical Association in New York when they were both fellow philosophy graduate students, colorful walking anomalies:

We had both been subjected to an unbelievable amount of staring by fellow professionals, which made us feel like exotic wildlife, and she had had to deal with requests for assistance by several philosophers who, despite her APA name tag, assumed she was on the hotel staff! In anger and frustration, she burst out, asking, “Why should I have to be the one to integrate the bus?” I am sorry to say that this remains a question for women of color in the profession more than a decade later, and it is one to which I have no better answer than I had earlier, which was “What choice do we have?” . . . If there is one thing I would like to see before I retire, it is philosophy becoming a profession where a generation of women of color do not feel these huge institutional burdens of integrating the academic and philosophical bus. (2003: 92)

But how is this integration to be accomplished? In his classic collection of interviews, African-American Philosophers: 17 Conversations, which can be seen as a kind of black oral history of the profession, editor George Yancy interviews Adrian Piper, the first black woman philosopher to be tenured in the United States. Yancy asks: “How can we get more Black women in the profession of philosophy?” And Piper replies frankly: “I think about this a great deal and I think the problem about getting Black women into the profession is that if you tell them what it is really like, no rational Black woman would want to go into it” (1998: 59). Similarly Anita Allen, with the advantage of a J.D. from Harvard Law School as well as a Ph.D. from the University of Michigan, exited philosophy departments (as her primary appointment) long ago for law school positions. She comments that black women have done “[e]xtra-ordinarily badly” in the field:

With all due respect, what does philosophy have to offer to Black women? It’s not obvious to me that philosophy has anything special to offer Black women today. I make this provocative claim to shift the burden to the discipline to explain why it is good enough for us; we should be tired of always having to explain how and prove that we are good enough for the discipline. . . . Any Black woman who has the smarts to do philosophy could do law, medicine, and politics with greater self-esteem, greater financial reward, greater visibility, and greater influence. Why bother with philosophy when there [are] so many other fields of endeavor where one can do better, more easily? This is the question that must be answered. (Yancy 1998: 172)

My hope, then, is that putting my and Pateman’s contracts together may be one useful way of creating a conceptual space in social and political philosophy to address nonwhite women’s distinctive concerns, thereby helping to make it somewhat more welcoming terrain than it currently is.

The natural starting-point is a rethinking and renaming of the system, the “basic structure,” involved. Pateman and I are both sympathetic to social-structural accounts, and so in our respective books we both found it natural to conceptualize domination in terms of a system, patriarchy for her, white supremacy for me. Obviously, then, the thing to do is to combine them, and in fact many feminists of color (largely outside of philosophy, of course) have long been doing precisely that, speaking variously of racial patriarchy, racist patriarchy, white supremacist patriarchy, and so forth.3 So it is important to be clear on the fact that outside of academic philosophy, these concepts have a long history, generated by the creative work and theoretical innovations of progressives in the activist movements of the 1960s and afterwards. The first question is whether such a structural approach is useful. Mary Maynard argues against postmodernist objections in terms of “difference,” suggesting that they elide questions of power and material advantage, not to mention foreclosing any broader global understanding of the socio-political order:

So many forms of difference are created that it becomes impossible to analyse them in terms of inequality or power. . . . The possibility of offering more structured socio-political explanations disappears, except in a localized sense, because these, necessarily, must be rooted in generalizations which cannot be made. There is, therefore, the danger of being unable to offer any interpretations that reach beyond the circumstances of the particular. . . . The deconstruction of categories such as race and gender may make visible the contradictions, mystifications, silences and hidden possibilities of which they are made up. But this is not the same as destroying or transcending the categories themselves, which clearly still play significant roles in how the social world is organized on a global scale. (2001: 129)

I share Maynard’s misgivings about postmodernism, and endorse her conclusions. So let us proceed under the assumption that, duly qualified, structural generalizations about the intersection of race and gender can be justified. The question now is whether they can be translated into a contract framework, and whether, even if they can, it contributes at all to the debate.

Pauline Schloesser is one political theorist who thinks they can, and that it does. In her book, The Fair Sex,about three leading female intellectuals of the early American revolutionary period (Mercy Otis Warren, Abigail Smith Adams, and Judith Sargent Murray), Schloesser comments, like Brace, that in Pateman and myself: “The study of male supremacy and white supremacy as two separate systems has led to awkward universals” about “male” and “racial” privilege, which obviously have to be qualified to register the realities of intersecting racial and gender subordination (2002: 49–50). However Schloesser expressly sets out to remedy this situation by trying to integrate our contracts, and to theorize racial patriarchy in contractual terms, and in effect I want to follow her lead.

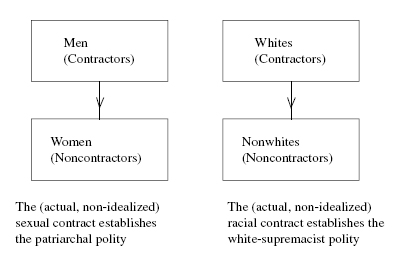

Refer now to the set of accompanying diagrams, which I think will assist the discussion by graphically representing the progression of the idea. In figure 1 we have the classic social contract (idealized, of course), in which all (adult) persons are contractors, symmetrically positioned with respect to one another, agreeing to establish an inclusive liberal democratic polity. So in the official narrative, as Pateman pointed out in her book (1988: ch. 1), the old world of inherited ascribed status is supposed to be replaced by the new world of egalitarian individual agreement.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

But of course it wasn’t. The contemporary idealized model, however pedagogically useful, retroactively sanitizes the gender and racial exclusions both in the classic social contract theorists and in the modern poli-ties their work rationalized. The ancient inferior status of women, seemingly a paradigmatic candidate for elimination by the promise of modernity, is recodified under the new system of “fraternal patriarchy,” while a new structure of superiority and inferiority, race, emerges to displace the (formal) class estates of the feudal epoch.4 Hence, in figure 2, the more accurate modeling proposed respectively by Pateman’s sexual contract and my racial contract. In these non-idealized representations, the real contractors are now revealed as a subset of the adult human population rather than being coextensive with it. Men and whites, whose superior status locates them asymmetrically, in relations of domination rather than reciprocity, over the noncontracting class of women and nonwhites, emerge as the real players. The sexual and racial contracts establish the patriarchal and white-supremacist polities.

Thus far, thus familiar. The sexual and racial contracts do undeniably capture some important truths about gender and racial subordination in modern societies, especially when compared with the nominally genderless and raceless social contract that was our polemical target. But as Brace and Schloesser point out, no interaction between them is described. However, once racial patriarchy has been established (and this is a specific historical development, not a transhistorical formation), the interlocking nature of the systems means that one cannot speak of the “contracts” in isolation, since they rewrite each other. Or, perhaps better (since patriarchy predates white supremacy, and the sexual contract – assuming a premodern incarnation – precedes the racial contract), the racial contract is written on patriarchal terms, and the sexual contract is rewritten on racial terms. As Maynard concludes: “It thus does not make sense to analyse ‘race’ and gender issues as if they constitute discrete systems of power” (2001: 131).

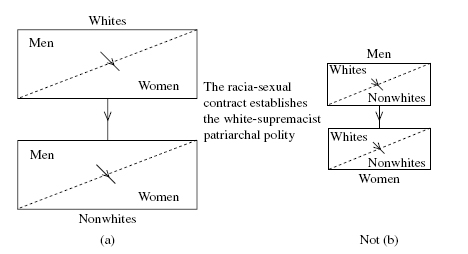

On then to figure 3, and the attempt to combine them. Here we have what I am going to call the racia-sexual contract (corresponding to “racial patriarchy”), in which pre-existing patriarchal structures are modified by the emergent new structure of racial domination. My claim is that though gender subordination predates racial subordination, once racial subordination has been established, it generally trumps gender. (As I will document later.) So the interaction of the two contracts does not produce a symmetry of race and gender subordination, but a pattern of internal asymmetries within the larger asymmetry of

Figure 4

social domination. Whites as a group dominate nonwhites as a group, while within these racial groups men generally dominate women (figure 3a). If you think this picture is wrong, just contemplate the alternative, figure 3b. Here men as a group dominate women as a group, with whites positioned over nonwhites in each sexual group. Ask yourself: does this model match up with, say, the historical experience of Native American and Australian expropriation, African slavery, European colonialism, South African apartheid, American Jim Crow? Do nonwhite men dominate white women in any of these situations? Obviously, the answer is “No.” So figure 3a gets it right and figure 3b gets it wrong. If the sexual contract establishes patriarchy, and the racial contract establishes white supremacy, the racia-sexual contract establishes the white-supremacist patriarchal polity.

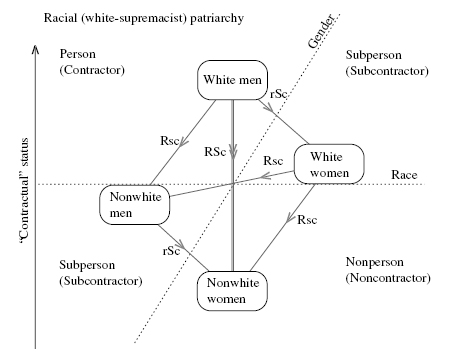

Turn now to figure 4, which could be regarded as a kind of “blowup” of figure 3a. In Pateman’s and my one-dimensional contracts, we had two status positions, one relation of domination (men over women, whites over nonwhites), and one set of contractors (men, whites). So in both cases, a simple dyadic relation – privileged at one end, oppressive at the other – obtained. The contractors, in the sense of the active agents, are respectively men and whites. Women and nonwhites are the objects of the contract rather than active participants (except in some coerced or ideologically socialized way that undermines the standard liberal norm of informed voluntary consent). So though the overall picture was more complex than the idealized, internally homogeneous social contract, it was still a fairly simple one.

In the racia-sexual contract, by contrast, a far more complicated topography is generated. As the asymmetrical diamond of figure 4 illustrates, we now have four contractual status positions with six relations of domination linking them. The four locations denote one position of unqualified privilege (white men, privileged by both race and gender), two hybrid intermediate positions involving both privilege and subordination (white women, privileged by race but subordinated by gender, and nonwhite men, privileged by gender but subordinated by race), and one position of unqualified subordination (nonwhite women, subordinated by both race and gender).5

The way to think of this set of relationships in “contractual” terms is then, I suggest, as follows. White men are located at the top of the diamond, as full persons, positioned superior to everybody else. They are thus the only full contractors of the composite racia-sexual contract, and so dominate all three other groups. White women and nonwhite men, by contrast, should be thought of as subcontractors,a term meant to indicate that (by contrast with the generic “women” and “nonwhites” of figure 2) they do have real, though inferior, power. They have a subordinate role in the global racia-sexual contract, typically being more active participants in one dimension of it than the other. (I signal this by the respective upper-case/lower-case, R/r and S/s, formulations of RSC, the racia-sexual contract, on the different intergroup axes.) White women, being on the wrong side of the (diagonal) gender line, are subordinated by white men through the sexual side of the racia-sexual contract, and are to that extent subpersons. But being on the right side of the (horizontal) racial line, they are located above both nonwhite men and nonwhite women, and so are in a position to dominate both. So the intermediate pair of white women and nonwhite men are not (I claim) symmetrically located with respect to each other – note the “tilt” of the diamond – since race lifts white women above nonwhite men. It is a mistake, then, to think that their “common” oppression by white men puts them in the same situation. White women are subcontractors of the racia-sexual contract to the extent that they assist in the racial subordination of people of color. Nonwhite men are also subcontractors, since they are participants in the sexual dimension of the racia-sexual contract. However, this will generally only be possible in connection with nonwhite women, at least in the contract’s classic stage, when racial subordination is overt and de jure. Finally, nonwhite women are at the bottom of the structure, dominated by all three groups: by white men through the racia-sexual contract in both its aspects, by white women through the racia-sexual contract (primarily) in its racial aspect, and by nonwhite men through the racia-sexual contract (primarily) in its gender aspect. If white men are full persons and full contractors, while white women and nonwhite men are subpersons and subcontractors, then nonwhite women are nonpersons and noncontractors.

The preceding discussion has necessarily been somewhat abstract and schematic. Let me now try to illustrate its applicability with concrete examples from the vast literature on intersectionality earlier mentioned.

(1) Mainstream liberal color-blindness and gender-blindness as simple blindness First, a general framing point. In the original classic social contract, as Pateman and I tried to demonstrate in our respective books, white males come together in the modern period under the self-description of “men” (or, occasionally, “persons”) to create (what I will now term) racial patriarchies. Contemporary contract theory retroactively sanitizes this history of exclusion and represents itself as universalist, the “men” (or “persons”) supposedly now (and then) including everybody. But insofar as the conceptions of the polity in the contract abstract away from this history of gender and racial subordination, they only contribute to its perpetuation. Susan Moller Okin (1989) famously pointed out the illusoriness of a political gender neutrality that is merely terminological. The contractors behind Rawls’s veil are supposed to be sexless heads of households, but in the range of problems they consider, and – more important – do not consider, they reveal themselves as actually male. Even more obviously, it can be argued, they reveal themselves as white, since they have no concern about such issues as affirmative action, reparations, land claims, the legacy (and continuing subtler incarnations) of white supremacy, and so forth.

So what is represented as simple innocuous philosophical abstraction per se, a standard and necessary tool of the discipline – the gender- and race-neutral language of “men” or “persons” – is actually an abstraction of a particular sort. It is an idealizing abstraction that in ignoring the effects of gender and race differentiation abstracts away from the concrete specifics of social oppression (O’Neill 1993; Mills 2005a). But the solution is not, in frustration, to reject abstraction itself as problematic, but rather to reject evasive abstractions – that obfuscate the crucial social realities that need to be mapped – in favor of non-idealizing abstractions – that reveal them. The racia-sexual contract, building on the racial and sexual contracts, does this by explicitly recognizing how race and gender position people differently, in complex asymmetrical interrelations, rather than pretending that we are featureless atomic individuals in egalitarian contractual relations with one another.

Judith Shklar points out that the reality in the United States, in opposition to the myth of a liberally all-inclusive polity, is that citizenship has crucially hinged on “social standing,” and that political theorists who ignore this history, especially “the part that slavery has played in our history,” “stand in acute danger of theorizing about nothing at all” (2001: 2, 9). (Think of the implications of this point for the “ideal theory” of Rawls’s Theory of Justice (1999h) – a book written by an American with no mention in its 500+ pages of the history of slavery in the United States and its legacy in the present.) In particular, the standing of white males as citizens was defined “very negatively, by distinguishing themselves from their inferiors, especially from slaves and occasionally from women” (Shklar 2001: 15). Indeed “black chattel slavery stood at the opposite social pole from full citizenship and so defined it” (2001: 16). Similarly, Evelyn Nakato Glenn argues that “the citizen and noncitizen were not just different; they were interdependent constructions. Rhetorically, the ‘citizen’ was defined and therefore gained meaning through its contrast with the oppositional concept of the ‘noncitizen’ (the alien, the slave, the woman)” (2002: 20).

So the actual civic interrelations of individuals in the United States – and, I would claim, elsewhere – are not the symmetrical and harmonious ones of idealized contract theory, but relations of domination and subordination. Apart from global gender differentiations, the moral status equality achieved in theory for males in general in contract theory is obviously hopelessly inappropriate as a characterization of the American polity, given its founding on a basis of racial hierarchy as a white settler state. Nor is it an accurate modeling of a tacitly intra-European liberal modernity that raises white Europeans everywhere, at home and abroad, above inferior nonwhite non-Europeans (Mehta 1999). Insofar as contract theory ignores this history, it is simply entrenching a hierarchy that, in more subtle forms, still exists today. By marginalizing the distinctive problems associated with gender and race, the mainstream contract – in effect, if not in self-description – is taking the white male as the paradigm contractor, and limiting its social justice prescriptions to his concerns. In contrast, the racia-sexual contract makes this status hierarchy explicit in its very apparatus, thereby pre-empting the theoretical evasion of these issues. By formally demarcating different subject positions, with their attendant privilege or disadvantage (or both), this non-ideal contract forces us to confront the question of what would be necessary to achieve ideality, rather than starting from that ideality. Louise Michele Newman condemns American liberalism’s typical “purposeful overlooking – a not-seeing – of difference, even when the consequences of such not-seeing lead to the maintenance of structures of oppression”:

The national romance with colorblindness, and its corollary, gender sameness, is a fundamentally misguided strategy (metaphorically, a two-headed ostrich with both heads in the sand) – an ineffective way to address the real discursive effects of social hierarchies intricately structured along the multiple axes of race, class, gender. . . . [P]eople of different races, classes, and genders are always already situated differently. To assert “sameness” is to purposefully ignore the material and ideological effects that race (gender, class, sexuality) have had in creating oppression, inequity, and injustice. (1999: 20)

But while I completely agree with the spirit of this indictment, I disagree with Newman’s implication that “egalitarian liberalism” is itself the problem. Rather the problem lies in a gender- and race-evasive liberalism which, in assuming sameness of status, has not been egalitarian, presupposing as long since accomplished an egalitarian goal that has yet to be achieved, thereby conceptually eliding the ongoing barriers to its realization. The racia-sexual contract confronts these problems by acknowledging the difference race and gender make, rather than pretending that they make no difference.

Moreover, it overcomes the dichotomization of Pateman’s and my partitioned contractual discourse. The sexual and racial contracts represented an advance on the nominally genderless and raceless social contract by recognizing the differential and inferior status within the contract of women and nonwhites. But in treating gender and race separately, the sexual and racial contracts generalize in a way that can be misleading. As Glenn puts it: “In studies of ‘race,’ men of color stood as the universal racial subject, while in studies of ‘gender,’ white women were positioned as the universal gendered subject” (2002: 6). Once racial patriarchy has been established, however, race and gender become intertwined, so that one has to speak of gendered race and racialized gender. What is true of white men is not necessarily true of whites as a group, or of men as a group; what is true of white women is not necessarily true of women as a group. I used a vocabulary of white persons and non-white subpersons, while Pateman described fraternally linked male patriarchs denying civil equality to inferior women. But white women whose legal personality is subsumed into their husbands’ by the doctrine of coverture can hardly be accurately characterized as full persons, nor under white supremacy does male fraternity extend across the color line to permit nonwhite rule over white women (Pateman 1988: 220–1), nor does either formulation explain the distinctive situation of women of color. The racia-sexual contract formally recognizes this more complex reality (while abstracting away, of course, from further complications) by overtly demarcating four contractual subject positions. Thus it pre-empts unqualified generalizations about “men” and “women,” “whites” and “nonwhites,” forcing us in each case to ask the question of what actually does hold true for the group in question, given their specific location in the composite multidimensional “contract.”

(2) White men as full persons and full contractors I will have the least to say about white men, since in a sense they were the primary topic of Pateman’s and my books, so that this has all been said already, if not within this revised framework. Located at the top of the diamond, privileged by both gender and race (albeit in some cases disadvantaged by other memberships, such as class or sexual orientation), they occupy the premier status position of the racia-sexual contract. As full persons, they are the paradigm contractors of mainstream social contract theory, originally overtly and de jure,now covertly and de facto through the assimilation of other subject positions to their status – which does not in the least make nonwhites and white women actually equal to them, of course, but only serves to obfuscate the latter groups’ continuing disadvantages. They are in a superior power relation to white women, nonwhite men, and nonwhite women, and the beneficiaries of the gender and/or racial exploitation of all three groups. Thus they will for that very reason be most susceptible to the delusions of race and gender ideology, since they have the greatest stake in maintaining the structure of illicit benefit and exploitation.

(3) White women as both subpersons and subcontractors The racia-sexual contract self-consciously breaks up the undifferentiated category of “women,” making it explicit that race as a structure of domination lifts white women into a category that is generally privileged with respect to their nonwhite sisters. Thus it registers in its apparatus the central, crucial accusation repeatedly made by women of color over the last three decades since the “second-wave” revival of feminist theory (as well as echoing earlier nineteenth-century “first-wave” grievances): that there is no “natural” sisterhood between the white plantation owner’s white wife and his black female slaves, between white settler women and the women of the Amerindian or Australian Aboriginal peoples being displaced, between the female white colonist in the European empires and the female nonwhite colonized, between Jane Crow and the Jane Crow-ed, between the white suburban housewife and her black or Latina domestic. It forces white women to recognize that white supremacy exists as well as gender domination, and that their subject location and contractual status are different from that of women subordinated by both.

As such, it challenges what Vicki Ruiz and Ellen DuBois call the “uniracial” model, in which “White women appear ‘raceless,’ their historical experiences determined solely by gender” (2000a: xi). Rather, in the words of Pauline Schloesser, white women are both “subjects” and “subjected” (2002: 8), “a racialized sex group,” “ambiguously positioned in the hierarchy of gender and race relative to white men and nonwhite persons of both sexes,” or, perhaps better, “doubly positioned, as subordinate others with respect to white men and as superior subjects with respect to nonwhites” (2002: 53). Contradictorily located, they are subpersons with respect to the white male, but are nonetheless superior to the different variety of nonwhite male subpersons, and certainly to the nonwhite female nonpersons. So while they may be objects for the subjecthood of the white male contractor, they are nonetheless subjects and subcontractors in their own right with respect to nonwhite men and women. Thus the theoretical challenge is to grasp, to somehow think simultaneously, both of these aspects of the contract, instead of letting one simply displace the other, so that white women are seen only as victims or only as oppressors.

In the early stages of second-wave Western feminism, the constant complaint by women of color was the condescension or outright racism of white feminists, so that it was white women’s subcontractual role that required highlighting given their self-positioning solely as victims. bell hooks writes about the US experience: “[White women] did not see us as equals. They did not treat us as equals. . . . From the time the women’s liberation movement began, individual black women went to groups. Many never returned after a first meeting” (2000: 141). Similarly, in her history of what she calls “separate roads to feminism” in the United States, Benita Roth argues that standard histories of the second wave “have erased the early and substantial activism of feminists of color embedded in these movements” (2004: 2), an activism necessitated by the fact that “racism within the (white) feminist movement was an inescapable issue, and racial division among feminists was the subject of many discussions and workshops” (2004: xi). (See also Breines 2006.) In Britain, likewise, Valerie Amos and Pratibha Parmar talk about the need to challenge the “imperial feminism” of the time: a “white, mainstream feminist theory, be it from the socialist feminist or radical feminist perspective, [which] does not speak to the experiences of Black women and where it attempts to do so it is often from a racist perspective and reasoning” (2001: 17). Thus for black women (“black” here including Afro-Caribbeans and Asians) the women’s movement in Britain, claiming to analyze and seeking to end oppression, was itself seen as “oppressive . . . both in terms of its practice and the theories which have sought to explain the nature of women’s oppression.”

From the structural perspective earlier adumbrated, of course, the point is that this is not just a matter of subjective attitudes and values but rather an outlook rooted in the objectively differentiated position of white women in the social order. In Roth’s account:

White women became the reference group for feminists of color, such that white feminists, as white women, were a group to be challenged for unfair advantages, just as white men were . . . based on an understanding of structural inequality. . . . African American and Chicana feminists . . . did not see [white women] as natural allies in the struggle for gender, racial/ethnic, and economic justice. . . . For feminists of color, structural inequalities among women mattered more than those between women and men within the racial/ethnic community. (2004: 44–6)

Moreover, as various accounts of the history of the women’s movement have documented, this differential positioning, with its resultant peculiar blindness and self-serving politics, goes back to the nineteenth or even eighteenth century and the “first wave.” Amos and Parmar point out that “the movement for female emancipation in Britain was closely linked to theories of racial superiority and Empire” (2001: 19). Similarly, Vron Ware argues that in imperial Britain “the ideology of white womanhood, structured by class and race, embraced women in all their familial roles”:

Whether as Mothers of the Empire or Britannia’s Daughters, women were able to symbolize the idea of moral strength that bound the great imperial family together. . . . Faced by this ideological burden, the writings of many feminists . . . show a fundamental tension in their attitudes to the idea of Empire. They might challenge or contest reactionary images of womanhood on which the imperialist project depended for support, but in doing so they expressed a lack of patriotism. Or they could adhere to their feminist principles, and effectively condone racist and imperialist policies which suppressed the freedom and independence of other people. . . . What was lacking was a vision of liberatory politics that connected the struggle against masculinist ideology and power with the struggle against racist domination in the colonies. (1992: 162–3)

So if the experience of gender subordination opened their eyes to feminist consciousness, the experience of racial privilege blinded them to the oppression of white supremacy.

But the implications of this lack of vision go deeper, affecting the very concepts central to white feminist theorizing. For both first- and second-wave white feminist theory, centered on the white woman’s experience, the family and the separation into private and public spheres are at the heart of women’s oppression. Patriarchy is the overarching theoretical concept that is supposed to cover the subordination of all women in its many different forms. However, with the establishment by global white supremacy of racial patriarchy as a distinct historical formation, the family will no longer be primary, even if it originally was, in the oppression of nonwhite women. Rather, it is their subordination through conquest, land expropriation, slavery, regimes of colonial forced labor, segregation, racialized occupational positions in the job marketplace, the sex industry, the modern sweatshop, and so forth, that becomes far more salient. Nor can it be said that women as a group are oppressed by being excluded from the public sphere, since it will often be the case that (as just cited) nonwhite women are in the public sphere, whether as slaves working in plantation economies, colonial laborers, domestics forced to seek employment in white households, or workers in racially and gender differentiated occupations.

Thus a far more complicated political geography than the simple Aristotelian dichotomization of (male) public polis/(female) private household is generated, so that the familiar white feminist cartographies inspired by this ancient partitioning, and its modern variant, will have to be redrawn. The subordination of nonwhite women will often be most manifest in racialized public sphere regimes of work and differential racia-gender exploitation (see, for example: Glenn 2002; Ehrenreich and Hochschild 2002), not in nonracial domestic gender exploitation by a nonwhite patriarch who confines one to one’s home. It is not that patriarchy is not manifest, but that racial patriarchy largely displaces power to whites as a group. The “patriarch” is, in a sense, the collective white population, with white men as the full contractors and white women as the subcontractors.

So in this revisionist picture, in opposition to white feminist orthodoxy, (white) women become active agents, if only on the subcontractual level, of (racial) patriarchy, insofar as they are complicit in the differential and inferior treatment both of nonwhite men and of their nonwhite sisters in systems of racial and gender subordination. In the racia-sexual contract, white women get to be patriarchs too,at least with respect to nonwhites. And in a sense, especially in the colonial world, nonwhite women in the public sphere are in the private sphere of the white patriarch, as minors subject to their paternal rule. The white “family” needs to be reconceptualized as writ large, on a national scale, with white women simultaneously subordinated individually in their private families and privileged collectively as co-rulers of the “national” or “international” public family. Antoinette Burton refers to the “maternal imperialism” of the period, involving “the white woman’s burden” (1992: 144), and Mary Procida, in her article on British imperialism in India as a “family business,” points out that for the Anglo-Indian rulers:

Husband and wife, together, embodied status and authority. . . . Their family business, therefore, was literally the business of empire in all its practical and ideological manifestations. . . . In the British Raj, Anglo-Indian women’s political power stemmed not from their position as citizens in a democratic polity (which the British empire obviously was not), but rather from their personal, social, and marital connections with imperial officials. As the wives of imperial officials and as members of the ruling race themselves, Anglo-Indian women . . . actively participated in the ongoing discourses of imperial politics. . . . They were married not only to their husbands; Anglo-Indian women were also married to the Raj itself. For women, therefore, their roles as wives allowed them not only to create their own biological families, but also to construct roles for themselves in the greater imperial family of British India and in the family business of empire. (2002: 168–9)

And within this extended “family,” “the colonized peoples of India took on, in the eyes of their British ‘guardians,’ the role of adopted children in the imperial family of the British empire,” if more as “troublesome stepchildren of the Raj than as the legitimate heirs to the family business of empire,” since because of race they “stood outside [its] genealogy and reproductive biology” (2002: 177). White wives as a collective memsahib assisted in the ruling of a “household” of inferior non-whites that was national in scope.

Similarly, Schloesser’s (2002) book is an analysis of how, in the United States, Mercy Otis Warren, Abigail Smith Adams, and Judith Sargent Murray, leading female intellectuals in the revolutionary period, all ended up – whatever their initial liberalism – by acquiescing to the terms of racial patriarchy. Through the endorsement of “fair sex” ideology, which differentiated them as white women from all males and from nonwhite females (black slaves, Native American “savages”), white women in the United States embraced a vision of themselves as a group possessing distinctive virtues and a particular civilizing mission in the early days of the republic. White female “subjectivity and agency,” then, were likely to manifest themselves in a severely qualified and restricted “feminism”:

[A] white woman concerned mainly with gender issues would attempt to view issues of sexual inequality in isolation from race and class issues, such that women of color, uneducated, or poor women would be largely invisible or irrelevant to her critical or reformist vision. In other words, a “feminist” would attempt to challenge the sexual contract while leaving intact the racial contract. . . . This strategy is basically an attempt to maximize one’s own power as a white woman by equalizing the opportunities between white men and white women without giving up racial privileges. (Schloesser 2002: 80–2)

In the new vocabulary I am suggesting, the racia-sexual contract recognizes, in its overt demarcation of four separate subject positions, with their accompanying dominant ideational tendencies and political options, an ideologico-political terrain more complex than that mapped by the sexual or racial contracts individually. So if The Racial Contract sketched a one-dimensional white blindness, an epistemology of racial ignorance afflicting undifferentiated white “contractors,” here one has simultaneous insight and sightlessness, the racia-gendered cognitive interplay of oppression and privilege. From the beginning, white women are so positioned in the diamond structure that a subcontractual role is open to them, making it not just possible but very likely that resistance to their gender subordination will coincide with their signing on to general nonwhite subordination. Very few white feminists took a principled stand against both aspects of the contract.

Thus Louise Newman’s book, White Women’s Rights (1999), explicitly subtitled The Racial Origins of Feminism in the United States, documents the conviction of most white women in the largely segregated feminist movements of the 1850s–1920s that they, as members of the superior race, should be “the primary definer and beneficiary of women’s rights,” and that this struggle was quite separate from issues of racial justice:

In the decades from 1870 to 1920 . . . despite moments of interracial cooperation, the woman’s movement remained largely segregated. Many white leaders dismissed the concerns of black women – such as miscegenation, interracial rape, lynching, and their admittance to the all-women cars on the Pullman trains – as “race questions,” irrelevant to the woman movement’s foremost goal of “political equality of women.”. . . . [W]hite activists had a heightened racial consciousness of themselves as civilized women. . . . Shared racial inheritance meant that men and women of the same race had more in common with one another than they did with the same sex of different races. (1999: 6, 7, 134)

As I claimed at the start, then, race generally trumped gender. Thus the primary concern for most white American feminists of the period was the achievement of gender equality with white men (joining the Herrengeschlecht of the Herrenvolk at the top of the diamond, and turning it, perhaps, into a simple rectangle), certainly not the ending of racial inequality. They were contesting the sexual dimension of the racia-sexual contract, but were quite happy to maintain its racial dimension, hoping, one could say, to move from the status of subcon-tractors to full contractors. In Newman’s uncompromising summary of her book’s thesis:

This book . . . rejects the premise that [white] feminism, in any of its late nineteenth- or early twentieth-century incarnations, was an egalitarian movement. . . . [F]eminism was part and parcel of the [United States’s] attempt to assimilate those peoples whom white elites designated as their racial inferiors. . . . Increased political power and freedom for white women was, in a material as well as ideological sense, dependent on asserting the racial inferiority and perpetuating the political subordination of nonwhite others. . . . In other words, racism was not just an unfortunate sideshow in the performances of feminist theory. Rather it was center stage: an integral, constitutive element in feminism’s overall understanding of citizenship, democracy, political self-possession, and equality. (1999: 181–3)

This demystified account provides the historical background for appreciating the deficiencies of second-wave feminism, making clear its continuity with the exclusionary political agendas and corollary distinctive blindnesses of the past, whether in the colonial world or in white settler states like the United States. If progress has been made recently in developing a less monochromatic, more democratic and inclusive feminism, it is because of the insights and criticisms of women of color, who were able from their vantage point to recognize in a way that most white feminists were not the racial dimension of mainstream feminism – that it was a specifically white feminism. By bringing race and gender together in the same framework, the racia-sexual contract acknowledges the conflicted coexistence of subordination and privilege in the situation of white women, and the corresponding need to theorize both on the multiple axes of cognition, exploitation, cultural representation, and political ideology and strategy.

(4) Nonwhite men as both subpersons and subcontractors We turn now to the other intermediate position in the diamond: nonwhite men. Like white women, they are both subpersons and subcontractors, but as I have emphasized, and tried to illustrate graphically in the tilt of the diamond, this is not an equivalence. Because race generally trumps gender in racial patriarchy, white women are originally positioned as superior not merely to nonwhite women but also to nonwhite men, though admittedly in a later more liberal period of the formation, this might change. White women are, after all, an integral part of the white family, the white household, in a way that nonwhites – slaves, savages, colonial populations – are not. (When domestic black slaves were part of the white household, it was obviously not on the same terms as white women.) The distinctive gender ideology of (white) complementarity, though undeniably demeaning and oppressive for women in its denial to them of full civic and political rights, does nonetheless link them with the superior white male apex of the diamond in a way that, say, racial ideologies of nonwhites as bestial, subhuman, in some cases exterminable, in most cases noncomplementary, do not. Thus if white women and nonwhite men are both – in the terminology I have suggested – sub-persons, they are not subpersons of the same type and moral/civic standing, since the racia-sexual connection with the full personhood of the white male underwrites white women’s status in a virtual way that has no equivalent for nonwhite men.

Moreover, and relatedly, the patriarchal relation between nonwhite men and nonwhite women should not be seen as equivalent to, or a black-faced version of, the patriarchal relation between white men and white women. Displacing the racial and sexual contracts with the composite racia-sexual contract requires us to rethink gender relations even when they are white-on-white and nonwhite-on-nonwhite. Male–female relations in the Europe and the Africa of, say, 1000 CE are (given the conventional periodization of the emergence of racism, and of race as a category) unaffected by race. So to describe them as white-on-white or black-on-black would be mistaken, since these categories and realities have no existence then. Once white supremacy is established, though (whether as racial slavery, nonwhite expropriation, or European colonial rule), and with it racial patriarchy, gender relations are changed since one is now interacting with someone of the opposite sex within a particular racial structure. Margaret Strobel emphasizes that: “Colonization transformed not only the material lives of colonized people, but also their sense of what it meant to be female and male” (2002: 57), and Chandra Talpade Mohanty refers to “the effects of colonial institutions and policies in transforming indigenous patriarchies” (1991: 15). Thus patriarchal relations even between people of (what are now categorized as) the same nonwhite “race” in, say, pre-invasion Native America and Australasia, or precolonial Africa and Asia, are necessarily going to be altered by the overarching reality in its different manifestations of white domination.

To begin with the obvious point: the shaping of the public sphere by “men,” so ideologically crucial to white feminist theory’s analyses of the causes of female subordination, will not generally be within the power of nonwhite men under racial patriarchy – as slaves, expropriated and reservation-confined aborigines, colonial populations, marginalized racial minorities – to accomplish. Rather, the public sphere, with its distinctive patterning of the functioning of the state, the legal system, the market, civil society, will be a white male creation, or a white male transformation of the pre-existing polity. Thus nonwhite males are originally in no position to play the kind of public patriarchal role, as powerful global arbiters of the topography of the sociopolitical, attributed simply to “males” in much of white feminist theory. Paula Giddings points out that under slavery, “slave women maintained their authority over the domestic domain – as women have traditionally done – while Black men had no authority over the traditional male spheres of influence” (1984: 58). Likewise, Hazel Carby, in a classic critique of white feminism, asserts, “It bears repetition that black men have not held the same patriarchal positions of power that the white males have established. . . . There are very obvious power structures in both colonial and slave social formations and they are predominantly patriarchal. However, the historically specific forms of racism force us to modify or alter the application of the term ‘patriarchy’ to black men” (1996: 67–8). Similarly, in criticizing Kate Millett’s generalization in her famous white feminist text Sexual Politics that “the military, industry, technology, universities, science, political office, and finance – in short, every avenue of power within the society, including the coercive force of the police, is entirely in male hands,” Elizabeth Spelman raises the obvious objection: “But surely that is white male supremacy. Since when did Black males have such institutionally based power, in what Millett calls ‘our culture’?” (2001: 77). Or consider coverture, another key concept in understanding white female subordination. Schloesser argues that “one’s status in slavery nullified the protections of coverture; if either husband or wife was enslaved, the owner retained his or her right to treat his or her slave as property. Thus, patriarchal power of husbands over wives would have been disrupted at best. . . . These conditions suggest the primacy of the racial contract over the sexual contract” (2002: 33).

Understandably, then, nonwhite men have generally been seen by nonwhite women more as fellow oppressed than oppressors. The prime movers and shakers of the social order are not men as such but men of a particular race. And since race has generally trumped gender, as illustrated above, the dominant political tendency within nonwhite communities of all kinds has been the affirmation of racial solidarity over against the white oppressor (both male and female). Giddings writes that in the United States of the 1840s and 1850s, “All Black women abolitionists . . . were feminists. But when it came to a question of priorities, race, for most of them, came first” (1984: 55). Nor had this changed by the early twentieth century, in the years following the First World War: “[R]acial concerns overwhelmed those of sex. . . . [One Black feminist wrote]: ‘feminist efforts are directed chiefly toward the realization of the equality of the races, the sex struggle assuming a subordinate place’ ” (Giddings 1984: 183). And obviously in the anticolonial struggles and national liberation movements of the twentieth century, it was the white colonizing power and the European settler population who were seen as the primary enemies, not nonwhite men. Indeed, even for postcolonial, post-1960s second-wave feminism, Benita Roth suggests that in the United States: “[Feminists of color] rejected the idea that their relationships with the men in their communities were, or should be, equivalent to those that existed between white women and white men. . . . [C]ommunity as such was conceptualized as the entire racial/ethnic community in battle against white America’s domination” (2004: 43, 70).

Appreciating the realities of the racia-sexual contract, and the way it differentiates gender relations for the dominant and the subordinate races, thus helps us to understand what many white feminists of the time found quite mystifying: the refusal of many women of color to classify nonwhite men as part of the male “enemy.” The overarching racial domination by whites invests the nonwhite male–female relationship with a dimension of joint transgender solidarity against oppression that will necessarily be absent in the gender relations of the privileged race.

Correspondingly, the nonwhite family and home will often be seen in terms quite different from those of white feminist theory. Under the terms of the racia-sexual contract, it is white supremacy that is crucially responsible for the subordinate status of nonwhite women, whether as white expropriation, slavery, colonial rule, or segregation. Usually the nonwhite family will be a refuge from the oppression of white supremacy, even if patriarchal relations obtain there. So the relation of the white woman and the nonwhite woman to the family will not be equivalent. If under racial patriarchy, as suggested, the public sphere for nonwhites can be thought of as being under the private rule of the collective white patriarch, the nonwhite private sphere will sometimes be the locus, or nucleus, of an incipient counterpublic sphere, the only place where nonwhites can exercise their limited freedoms and seek to challenge white rule. Hazel Carby points out that “during slavery, periods of colonialism, and under the present authoritarian state [in 1980s Britain], the black family has been a site of political and cultural resistance to racism” (1996: 64). It is a mistake, then, to see the family as the main source, transracially, of gender oppression, since for non-white women it may also be the place where opposition to the “patriarchal” rule of the global White Father and Mother is nurtured. So the classic white feminist slogan of the personal as the political acquires an alternative significance here, reflecting this more complex topography. If the public political sphere can for nonwhites in certain regimes be conceptualized as also being part of the white personal familial sphere, then the nonwhite personal sphere can sometimes serve as the virtual location of the beginnings of the oppositional nonwhite political sphere.

But these very structural realities, of course, can also facilitate the subcontractual role of nonwhite men in the racia-sexual contract. For both intermediate groups, white women and nonwhite men, the racia-sexual contract offers the option, which will be both ideologically dominant and politically most appealing, of a partitioned struggle against one aspect of the contract that meanwhile maintains the other. Subcontracting will always seem more attractive than fighting for the tearing up of the contract altogether. The racialization of all gender relations – not merely interracial gender relations – means that non-white men will benefit from, and be cognitively influenced by, the status positioning of nonwhite women at the bottom of the diamond. So if most white feminists sought gender equality within white racial superiority, most nonwhite male antiracist activists sought the restoration of traditional male privilege unqualified by race.

Thus the struggle for black “manhood” – think of the celebrated placard carried by black demonstrators in the United States in the 1950s and 1960s, “I AM A MAN” – usually meant, inter alia, the struggle for the restoration of the full range of nonwhite masculine gender privileges taken away by racial patriarchy, an end to the racial subordination of black men as mere subcontractors rather than fully and equally privileged male contractors. Activist Pauli Murray wrote in 1970:

The black militant’s cry for the retrieval of black manhood suggests . . . an association of masculinity with male dominance. . . . Reading through much of the current literature on the black revolution, one is left with the impression that for all the rhetoric about self-determination, the main thrust of black militancy is a bid of black males to share power with white males in a continuing patriarchal society in which both black and white females are relegated to a secondary status. . . . [T]he restoration of the black male to his lost manhood must take precedence over the claims of black women to equalitarian status. (1995: 187–90)

Similarly, in her mordant memoir of the “revolutionary” 1960s and 1970s, Michele Wallace recalls the gender-restricted nature of the “struggle” of the time:

It took me three years to . . . understand that the countless speeches that all began “the black man. . .” did not include me. I learned. I mingled more and more with a black crowd, attended the conferences and rallies and parties and talked with some of the most loquacious of my brothers in blackness, and as I pieced together the ideal that was being presented for me to emulate, I discovered my newfound freedoms being stripped from me, one after another. No, I wasn’t to wear makeup, but yes, I had to wear long skirts that I could barely walk in. No, I wasn’t to go to the beauty parlor, but yes, I was to spend hours cornrolling my hair. No, I wasn’t to flirt with or take shit off white men, but yes, I was to sleep with and take unending shit off black men. . . . [T]he “new blackness” was fast becoming the new slavery for sisters. (1995: 221–3)

So nonwhite men were generally opposed to a racia-sexual contract that denied them male equality and gave white men access to “their” women. But the dominant response was not (and is still not) a demand for the outright leveling of the diamond structure, but rather for the clearing of a space for them at its apex. In The Sexual Contract (1988), Pateman describes the gender transition from feudal status to modernity in terms of the replacement of paternal patriarchy by fraternal patriarchy. Here the analogous goal is the replacement of racial patriarchy by transracial patriarchy, of the white-imposed racia-sexual contract by the raceless sexual contract. The trumping of gender by race in the structure of privilege can then be exploited by nonwhite men to demand of women of color a transgender solidarity against white racist oppression that denies nonwhite men’s subcontractual role in the racia-sexual contract, and represents any alliance with white feminists as a kind of treachery. In the words of former Black Panther party leader Elaine Brown: “A woman attempting the role of leadership was, to my proud black Brothers, making an alliance with the ‘counter-revolutionary, man-hating, lesbian, feminist white bitches’ ” (cited in Breines 2006: 57).

In her 1982 introduction to the first edition of Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology, Barbara Smith listed various “myths” devised by “Black men . . . to divert Black women from our own freedom,” including the claims that “Racism is the primary (or only) oppression Black women have to confront,” “Feminism is nothing but man-hating,” and “Women’s issues are narrow, apolitical concerns. People of color need to deal with the ‘larger struggle’ ” (2000a: xxviii–xxxi). Nearly 20 years later, in her 1999 preface to a new edition, she laments how little has changed outside the academy: “To this day most Black women are unwilling to jeopardize their racial credibility (as defined by Black men) to address the reality of sexism. . . . [I]t has been extremely difficult to convince most in the Black community to take Black women’s oppression seriously” (2000b: xiv–xv). She quotes Jill Nelson: “To be concerned with any gender issue is, by and large, still dismissed as a ‘white woman’s thing’. . . . Even when lip service is given to sexism as a valid concern, it is at best a secondary issue. First and foremost is racism and the ways it impacts black men” (Nelson 1997: 156).

In effect, then, continuing nonwhite male benefit from racial patriarchy is denied, and the role of nonwhite men as subcontractual signa-tories is obscured. An overcoming of both of the contract’s dimensions will require a demystified confrontation with the fact that, like white women, nonwhite men do gain something from the terms of the contract, and that if sex is racially differentiated, race is gender differentiated. Nonwhite men, like white women, are subcontractual subjects and agents as well as oppressed victims. Gloria Anzaldúa writes about Chicano machismo:

[“M]achismo” is an adaptation to oppression and poverty and low self-esteem. It is the result of hierarchical male dominance. . . . The loss of a sense of dignity and respect in the macho breeds a false machismo which leads him to put down women and even to brutalize them. . . . Though we “understand” the root causes of male hatred and fear, and the subsequent wounding of women, we do not excuse, we do not condone, and we will no longer put up with it. . . . As long as woman is put down, the Indian and the Black in all of us is put down. (2001: 99)

So in this revisionist picture, nonwhite men who resist the struggles for equality of nonwhite women are in effect subcontractually complicit with the role of white racism in confining them to the bottom of the social structure. In the racia-sexual contract, nonwhite men get to be white supremacists too,at least with respect to nonwhite women.

(5) Nonwhite women as nonpersons and noncontractors We come now to our primary subject of concern: nonwhite women. Originally located at the bottom of the diamond, disadvantaged by both gender and race, they do not even attain the qualified status and limited benefits of the two intermediate groups. So if the latter are at least subcontractors, if not full contractors, and subpersons, if not full persons, nonwhite women could be said to start off as noncontractors and nonpersons, subordinated by white men, nonwhite men, and white women.

The positioning of all three other groups gives them a greater or lesser material interest in blinding themselves to pertinent social realities. White men’s ignorance will be greatest and most systematic, but white women and nonwhite men will have their particular blinders also. Only nonwhite women will have no vested interest in privilege, which does not, of course, mean that their cognitions will automatically be veridical, but means that they will have no group interest, as others do, in getting things wrong. It should be unsurprising, then, that from the start it is nonwhite women who have been the intellectual pioneers of this “intersectionalist” perspective, a feat all the more impressive considering that precisely because of their status they will usually have been the ones with the least access to education, and the ones facing the greatest epistemic barriers to their credibility. So they will find it more difficult to speak in the first place, and more difficult to be taken seriously even when they are heard (if they are).

Anna Julia Cooper pointed out that “[The colored woman] is confronted by both a woman question and a race problem, and is as yet an unknown or unacknowledged factor in both” (1998: 112–13). Sojourner Truth complained in 1867: “There is a great stir about colored men getting their rights, but not a word about the colored women; and if colored men get their rights, and not colored women get theirs, there will be a bad time about it” (Truth 1995: 37). In effect, women of color have had to fight on multiple fronts, against the racism of their own sex and the sexism of their own race. They have experienced the racia-sexual contract in full unmitigated force and from all directions at once (see figure 4). Thus it has been clearer to them than to others that what has variously been called “a single-axis framework” (Crenshaw 2000: 208), “a monist politics” (King 1995: 299), is necessarily going to be inadequate. Different metaphors have been used to express the complex intersectionality of their experience, but one of the most popular is Deborah King’s insistence that nonwhite women do not experience race and gender as “additive,” but as “multiplicative.” Thus in what is seen as a classic 1988 paper, she rejects earlier models of “double” or even “triple” jeopardy:

The experience of black women is apparently assumed, though never explicitly stated, to be synonymous with that of either black males or white females. . . . It is mistakenly granted that either there is no difference in being black and female from being generically black (i.e., male) or generically female (i.e., white). . . . [T]he concepts of double and triple jeopardy have been overly simplistic in assuming that the relationships among the various discriminations are merely additive. . . . An interactive model, which I have termed multiple jeopardy, better captures those processes. The modifier “multiple” refers not only to several, simultaneous oppressions but to the multiplicative relationships among them as well. (King 1995: 295–7)

Obviously, then, neither the sexual nor the racial contracts, whether individually or additively, will succeed in mapping this reality. Instead, nonwhite women will fall between theoretical stools (refer back to figure 2: think of this as a literal graphic representation of the theoretical alternatives). Insofar as the sexual contract takes white women’s experience as normative, insofar as the racial contract takes nonwhite men’s experience as normative, nonwhite women will be squeezed out. As Kimberlé Crenshaw writes: “[Because of] the tendency to treat race and gender as mutually exclusive categories of experience and analysis . . . Black women are theoretically erased” (2000: 208). Similarly, Elizabeth Spelman (2001) refers to “the ampersand problem in feminist thought,” the difficult challenge of thinking race and gender together. Kum-Kum Bhavnani suggests that in effect women of color will either be rendered “invisible” or appear as “merely an ‘add-on’ ” (2001a: 4). Likewise, Angela Harris describes what she calls the “nuance theory,” where one starts from white women as “the norm, or pure, essential Woman,” and then makes generalizations about “all women” with “qualifying statements, often in footnotes”: “the result is that black women become white women, only more so” (2000: 162). The ways in which race modifies gender and gender modifies race will not be part of the theoretical apparatus: appropriate concepts, narratives, “multiplicative” realities, will be missing. Instead the cognitive tendency will be to try to assimilate the experience of nonwhite women to one or the other of the two conceptual frameworks: women (nominally colorless, but tacitly white) and nonwhites (nominally genderless, but tacitly male).

But as the Combahee River Collective announced in their famous pioneering black feminist statement: “[T]he major systems of oppression are interlocking. The synthesis of these oppressions creates the conditions of our lives. . . . We know that there is such a thing as racial-sexual oppression which is neither solely racial nor solely sexual” (2000: 261, 264). In the “contractual” translation of these claims that I am advocating, the racia-sexual contract registers this interlocking and multiplicity, recognizing that nonwhite women have a distinct location in the diamond, one that is separate from both nonwhite men and white women, with peculiar “contractual” features of its own. Thus the formal partitioning of the different subject positions requires us to think through how these different aspects of the contract will impact nonwhite women. In the absence of such differentiation, one will fall back on concepts and tropes that are insensitive to the peculiarities of their position, assimilating it to one or the other of the terms of the sexual or racial contracts on their own.

To begin with, by virtue (vice?) of being nonwhite, women of color, like men of color, fall on the wrong side of the racial line that, with the establishment of global white supremacy, demarcates the civilized from the primitive and savage. Thus the nonwhite woman is immediately differentiated from the white woman by her racial inferiority, and as such is necessarily located in a different category, which is why any conceptual apparatus presupposing a homogeneous gender status is going to be wrong from the start.

Moreover, white women were not merely civilized but, as we saw earlier in the discussion of Louise Newman, agents of civilization, having a “unique role” “as civilizers of racially inferior peoples,” “civilization-workers” exercising “cultural authority over those they conceived as their evolutionary and racial inferiors” (1999: 21, 53). In the iconography of the West, the white woman, in keeping with her contradictory location, has been glorified as well as degraded, chosen in paintings, sculpture, statuary, and monuments as an appropriate figure to represent Civilization, Progress, Culture, Europe, Justice, Liberty, and so on. For the woman of color, on the other hand, noncontradictorily, unequivocally, located at the bottom of the diamond, it has been simple degradation without glorification. The Statue of Liberty, so emblematic of the United States, is not merely a woman – certainly not a generic woman – but a white woman. Can one imagine a black or Native American woman as the Statue of Liberty? Rather, the black woman’s contrasting status in the national iconography is summed up by a 1920s proposal by the Daughters of the Confederacy (fortunately not implemented) “to erect a statue in Washington, D.C., in memory of ‘Black Mammies’ ” (Giddings 1984: 184). Where women of color appear, it is as the Savagery, Backwardness, Nature, Africa/Asia/Aboriginal America, Bondage that need to be enlightened and liberated, the Servility that smilingly accepts its subordinate place, or the illicit Carnality that threatens the white family.

Morally, then, nonwhite women’s location at the bottom of the racia-sexual contract lowers them normatively beneath the subpersonhood of white women, who were, after all, when all is said and done, the mothers, wives, sisters, daughters, of white men. While some white women might have fallen short of the (original) virginal ideal, nonwhite women as a class – especially black women – were seen as unchaste, naturally promiscuous, likely to be infected with sexually transmitted diseases of various kinds. Antoinette Burton points out that women of India were, in the “feminist-imperial hierarchy” of the nineteenth century’s “Orientalist” views of female sexuality, judged to be “inherently licentious and immoral” (1992: 143). Chandra Talpade Mohanty quotes from a US Exclusion Act which, based on the 1870 hearings on Chinese prostitution, “assumed that all ‘Oriental women’ wanting to emigrate would engage in ‘criminal and demoralizing acts’ ” (1991: 25). Paula Giddings cites an English slave trader’s description of black women as “hot constitution’d ladies,” possessed of a “lascivious temper” (1984: 35). Indeed, this was “scientifically” backed up (in different ways) by the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century racial science of theorists like George Buffon and J. J. Virey, who singled out black women in particular as embodied epitomes of a primitive and bestial sexuality (Gilman 1986). Similarly, Kimberlé Crenshaw cites a 1918 law court characterization of blacks as a “race that is largely immoral,” and a 1902 commentator’s view that “the idea [of a virtuous Negro woman] is . . . absolutely inconceivable to me” (2000: 234 n48), the corollary being that, by contrast with white women, “there has been absolutely no [white] institutional effort to regulate Black female chastity” (2000: 223). If some white women were fallen, no black woman was capable of rising to a level from which she could fall. There is a sense, indeed, in which black women’s genitalia were not “private parts” but “public parts,” open by their very nature to the scrutiny and access of the inquiring white gaze, as illustrated by the horrific story of Sarah (Saartjie) Baartman, the so-called Hottentot Venus (Holmes 2007). The racia-sexual contract deprives nonwhite women as a group of the protections that at least some white women had, making them carnality incarnate, whereas in the case of white women, as Richard Dyer (1997) argues, whiteness is so linked to the spiritual, to the disembodied, that sexuality can be combined with, redeemed by, the disincarnating spirit of white racial metacorporeality. So whites, but not blacks, get to have it both ways. Not Civilization, Progress, Culture, but National Mammy, Transnational Pudendum – such were the defining images of the black woman.

The racia-sexual contract therefore shapes conceptions of sexuality and femininity aesthetically as well as morally. The nonwhite woman, especially the darker nonwhite woman, is uglier as well as lower. The fetishization of the white female body extends, of course, beyond the symbolic and metaphoric to the libidinal. In his study of somaesthetic whiteness, Richard Dyer points out that “In [the] Western tradition, white is beautiful because it is the color of virtue,” so that, in a 1950s ad for Lux toilet soap, illustrated by a white movie star, “cultural symbol (classical antiquity), product and effect are all linked by the idea of whiteness as, in [Jackie] Stacey’s words, ‘purity, cleanliness, beauty and civilized culture’ and by the attainment of ideal (therefore implicitly white) feminine beauty” (1997: 72, 78). So even if this ethereal ideal is out of reach for the average white woman, she is at least visually categorized within the same somatotype, as against the woman of color whose features disqualify her from the start.