The rebels had to find a hiding place for their weapons: forty-seven Italian 6.5 mm Carcano carbine rifles. Redondo and others volunteered to drag the guns down a trail so that they could stash them in one of the underground caves.

The other group, led by Menoyo, had to move quickly to a trail that stretched west into the next ring of hills.

They knew the wide sweeping terrain, and they knew the guajiros who had given them food and even their rusty old shotguns and knives. The rebels needed to stay out of the line of fire—and out of sight of Batista’s men—until they could reach safety.

Menoyo’s group scurried along the trail, stopping every few hundred yards to make sure no aircraft were soaring overhead. As soon as they found tree cover, they would wait until night to move again. For Morgan, it was a rough start. They had to flee because he had screwed up. This is what he got for not knowing the language. He wasn’t going to be able to survive without learning it.

Menoyo was still angry at him for blowing their cover. But what really concerned him was that the Second Front wasn’t ready for a serious confrontation with the enemy, and the soldiers were going to catch up with them.

No one in the Second Front understood the importance of experience and military training as much as Menoyo. Growing up in Spain in the 1930s, he watched as his family took up arms to protect themselves from Francisco Franco’s soldiers during the Spanish Civil War. One of his older brothers, José, was killed at age sixteen during the conflict.

Not long after, another member of the family, Carlos, decided he was going to leave home to fight for freedom but against a new enemy: the Nazis. He joined the forces of Jacques-Philippe Leclerc in the liberation of Paris, and twice the French government decorated him.

Like his brothers, Menoyo was expected to take his place at the revolutionary table, even after the family moved to Havana after the war. Menoyo’s father, a physician, was passionate about his political beliefs, condemning all forms of dictatorship. Even in his newly adopted country, he never wavered. After Batista seized power in 1952, the family aligned itself with the growing underground movement against the dictator.

The eldest brother, Carlos, quickly gained a following among the young student radicals. Smart and charismatic, he desperately had wanted to leave a mark on the growing rebellion. In March 1957, he led the attack on the presidential palace, but he wouldn’t let his little brother, Eloy, join the assault. The family couldn’t afford to lose two more sons if the plan failed.

Carlos led the commandos into the palace, tossing hand grenades as they made their way inside. Unable to find Batista, Carlos and his men bolted to a set of stairs but were quickly met by guards, who gunned them down. Eloy was devastated. Nothing was going to stop him from throwing himself into the revolution.

Where Carlos had been fiery, Eloy was quieter and reserved. Frail with thick, dark glasses, Eloy Gutiérrez Menoyo looked more like a college professor than a guerrilla leader. But when anger rose up inside him, he cast a cold, steely stare. He had large shoes to fill and not a lot of time to prove himself. This was a critical juncture in his command.

For two days, the men kept to the trail, walking mostly at night to avoid being spotted. They talked little, fearing that their voices would carry on the wind. They weren’t allowed to smoke, and they stopped only to fill their canteens. They were exhausted.

Hours passed before they could sleep, making it harder to cut through the thick shrubs. Slowing each man was a knapsack stuffed with clothes, blankets, bandages, cans of condensed milk, ammunition, a hammock, and a nylon sheet to shield against the rain. Everyone pushed on until in the distance Menoyo finally saw the familiar row of sabal palms along the creek leading to Finca Diana. The farm set high in the foothills of the Escambray should have served as a welcome sight. But for the rebels, it was a painful memory.

Months earlier, Batista’s soldiers had surrounded the fledgling rebel unit, which was lucky enough to escape into a nearby jungle, losing just one man. Not long after, the soldiers hunted down the rebels near the farm, this time killing six—a quarter of the entire unit—on Christmas Day. Some of the rebels were close to giving up, but Menoyo refused to let them return to their homes. If they had even a shred of a chance of overthrowing Batista, it was here in the mountains, the hinterland, not the cities and certainly not Havana. They needed to stick it out until they had gathered enough men and weapons.

Menoyo had learned after watching his brother die in the disastrous attack on the presidential palace that the rebels needed to pull Batista and his men from their comfort zone—like Castro had done—into the mountains. They had to engage in guerrilla warfare.

The sun was rising over the mountains and Menoyo and his men were about to set up camp when word came from one of their scouts: The soldiers were in view.

He couldn’t count them all, but at least a dozen were moving down a deer trail toward their position. Menoyo ordered the rebels to take cover with a clear view of the trail below and to wait for his orders.

This time, Morgan was ready, clutching his rifle. He was determined not to mess up.

With the rebels lined up on both sides, the soldiers came into view. Menoyo waited. Tres . . . dos . . . uno . . .

Finally, Menoyo motioned for the rebels to fire. Gunshots cracked from the ridge above. The surprised soldiers jumped for cover. Morgan stood up over the other rebels, gripping his rifle, as his rounds sliced through the brush, hitting the trees and ground below. The others stayed down and in place, but Morgan stood up and kept moving forward.

Some of the soldiers took position and fired back, but it was impossible to get clear shots by aiming upward. In just twenty minutes, the soldiers realized they were going to have to retreat or get pinned down and die. One by one, they stopped firing and retreated. For the first time, Menoyo and his men had repelled the enemy without running.

It was calm for now, but Menoyo knew the soldiers would return with more men and firepower.

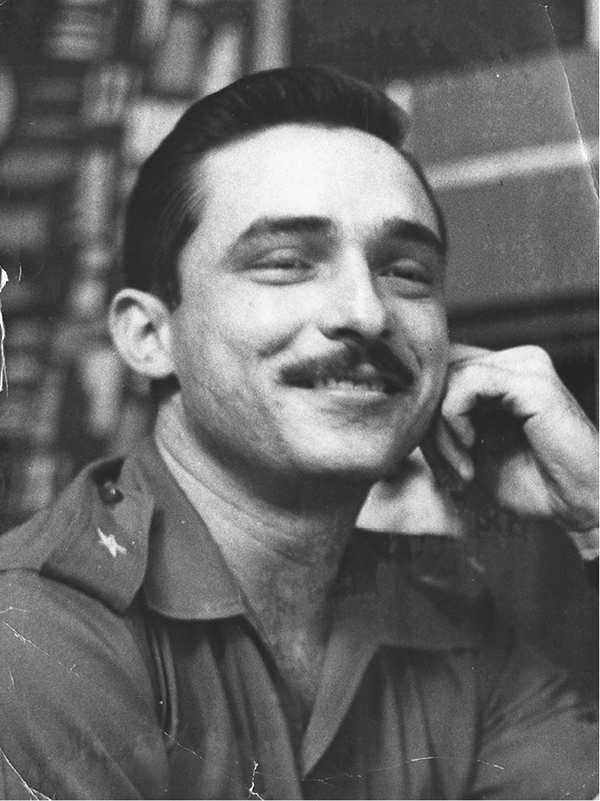

Jesús Carreras Zayas, one of the comandantes of the Second Front Courtesy of Morgan Family Collection

A half mile from the skirmish, he could see the rocks jutting out from high above the pass. As the men neared the farm, Menoyo spotted the ridge. If they could reach that point, they could set up camp, wait for the soldiers to return, and launch another ambush.

Menoyo knew the soldiers would be bringing an entire company—and they’d be angry. If they, a ragtag band of rebel farmers, beat them twice, the soldiers would be humiliated before their superiors.

As they trudged up the steep hill, Menoyo decided to pull out their most formidable weapon: a Czech submachine gun they kept for just this reason. A light model made just after World War II, the weapon was capable of spitting out 650 rounds per minute. It was all they had.

The man carrying the Czech gun, Jesús Carreras Zayas, had been with him from the beginning. The quiet, brooding rebel had left his job as a lab technician in the southern coastal town of Trinidad. Tough and ornery, Carreras drank and got into scrapes, bragging that he wasn’t afraid of anyone. Most of the time, that was true. During the early days of the anti-Batista movement, Carreras was set up by an undercover agent working for the government. Rather than risk arrest, he jumped in a Jeep, shot the agent, and took off, taking a bullet in the shoulder in the process but managing to escape. Menoyo ordered Carreras to set up the machine gun, picking a spot with just enough range to spray the entire trail with bullets.

After taking time to scout the area, Menoyo directed some of the men to take positions along the high ground—one here, another there, others far to the right and left. Then he counted out more men and moved them to the rear. This way, the rebels could conceal their own numbers so the soldiers had no idea the size of the force they were fighting.

Menoyo dragged his knapsack and his M3 submachine gun to a point above the trail, sat down, and waited. The sun beat down on the men as they clutched their weapons.

Any faint sound—the snapping of branches, the flutter of birds scurrying from a nest—would be their sign. By three o’clock, one of the scouts rushed back. “Vienen,” he whispered. They’re coming—two hundred, maybe more, on the trail.

Menoyo was right. They were coming back with more men. Once again, Morgan gripped his rifle and took aim. As the first few soldiers appeared on the trail, Menoyo waited. Not yet. The more soldiers on the trail, the more they could surprise them, and the more casualties they could inflict.

Wait. Wait.

Menoyo gave the signal. Carreras opened up, unleashing a barrage that ripped into the earth. Some of the soldiers fell down, struck by bullets; others ran for cover.

Pinned down, the soldiers began firing back to stop the attack. “There was no place they could pass,” Redondo recalled.

The soldiers were in chaos. Some were screaming on the ground. Others were trying to get away. As the two sides came closer, two of the rebels were hit.

Once again, Morgan rose above the fray, clutching his rifle, and now—standing up—began firing on the enemy in a frenzy. While the others looked on, Morgan continued moving forward, bullets flying on both sides, shooting round after round. The enemy slowly fell back, some retreating down the path by which they had come, others scrambling into the brush.

After several more minutes, it was over. Except for the dozen soldiers dead on the ground, the company had disappeared. The rebels waited several minutes, no one moving. Then, one by one, they walked down from the ledge.

They had done it. They had repelled at least two hundred soldiers in the same place where the army once had run them into the hills. The younger men stared at Morgan. They had never seen anyone stand up in battle and fire, refusing to take cover. “Está loco,” they said. He’s crazy.

Even Menoyo stopped for a moment and looked at his Americano guerrilla. He saw something in Morgan that he hadn’t seen in the others. When the bullets were flying, the Americano didn’t retreat. In a revolution that was about to get nasty, Menoyo was going to need him.

No one had expected this, not the military leadership and certainly not the farmers who waited until dawn to venture to the ridge. More than a dozen men in uniforms—Batista soldiers—lay sprawled on the ground, their bodies riddled with bullets. The farmers were stunned. They knew about the battle, but they thought they would be burying rebels, not soldiers.

They couldn’t leave the cadavers rotting in the sun, so they lifted them up and threw them on the backs of their horses. One by one, the horses moved down the path, the bodies tied to their backs. At El Pinto, the local store, the locals whispered among themselves about what had happened. Months earlier, they had watched as the guerrillas retreated. Now they were seeing something far different.

“It was important for the whole area,” recalled Armando Fleites Diaz, one of the rebels. “We made a stand.”

Word spread to nearby towns.

Redondo, the rebel who had split from the unit days earlier to hide the guns, heard about the rebel victory miles away in another town. By then, the stories had grown. “They were talking about the bearded, six-foot guerrillas,” he recalled. But it was clear the victory at Finca Diana was having an impact on recruiting new members in the Escambray. Scores of farmers began showing up in the mountains, asking to join the Second Front.