Olga opened her eyes just wide enough to make out the nurse carrying the tiny bundle in her arms. The last thing she remembered was being wheeled into the delivery room with Morgan and the escorts waiting in the hall outside. It all had happened so quickly. One minute, she was shopping in a grocery store, and the next, her escorts were rushing her to the hospital.

She reached up and took the baby into her arms.

“Congratulations,” the nurse said, “you have another daughter.”

Pulling back the covers, Olga smiled as she gazed at the tiny infant in her arms. She and Morgan had already agreed that if she had a girl they would name her Olga. For a moment, she forgot about everything: the arrests, the guns, Morgan’s health.

The last nine months had been the most difficult of her life. But looking down on the little baby on her chest, she was overwhelmed. It had been a long time since she had felt this much peace. She barely noticed that Morgan was standing over her, smiling. He leaned down and kissed her and then grabbed her hand.

“A baby girl,” he said.

The last thing Olga remembered him saying was that they were going to have a son. But Olga knew her husband couldn’t resist any baby—boy or girl. Morgan gently kissed his infant daughter and held Olga’s hand. He kidded that they would have more children and he would “finally get my boy.”

But Olga stopped him. “Come closer,” she said. “I want to tell you something.”

He leaned over.

“We don’t have any more time,” she said. “Remember that we are in the middle of serious problems. Very soon we will have to take another road.”

She was right, but Morgan didn’t want her to dwell on their problems, not now. “You get some rest,” he said. He wanted her to be at ease for one moment at least. Soon enough it was all going to change.

Before sundown, Roger Redondo had all the information he needed. The old cargo ship sat docked in the hidden port. The men aboard had unloaded the containers already. No one was supposed to know the origin of the ship, not the dockworkers nor the townspeople. But Redondo knew everything.

After thanking his sources, he sped toward Havana. He always prided himself on turning up actionable intelligence for the Second Front, whether locating an enemy company in the mountains or tracking down desperately needed rifles. This was different.

Most of the information was sketchy, but Redondo learned that the ship that had just slipped into the port near Trinidad belonged to the Soviets. No one knew where the vessel had last departed, but men speaking Russian had been seen getting off the boat. Russians rarely if ever ventured into this part of the country. Soviet cargo went to Havana.

More details surfaced when one of the men from the boat made a trip to the sprawling sanitarium, Topes de Collantes, fifteen miles away. Angelito Martinez, a Spanish Communist who fought in the Spanish Civil War and later taught military tactics to the Russian army in World War II, had gone to the director’s office demanding that the hospital’s cook prepare food for the men on his cargo ship.

At first, the kitchen manager refused. “The sick eat first, and then we’ll see what we can do for you,” he said.

Martinez, whose real name was Francisco Ciutat de Miguel, was fifty-one years old, and he wasn’t used to being rebuffed. He ordered that his men be fed and fed immediately.

Redondo needed to get word to Morgan. Soviet diplomats in Havana were no surprise. But Soviet military advisers showing up in a remote area of southern Cuba—a direct threat to the Second Front—certainly was.

Redondo told Morgan everything, including the Soviet agent’s demands at the sanitarium. As expected, Morgan bristled. Russian military advisers could have set foot in the country only at the open invitation of Fidel Castro. Worse, the presence of Communist military leaders in Cuba could mean only one thing: They were training Cuban soldiers.

“That son of a bitch,” Morgan said.

He had tried to put everything aside for the benefit of his men and his family. He had promised Olga that they would live in peace. But he couldn’t do it anymore—not in light of what he had just learned. This wasn’t just Castro’s country. It belonged to the people of Cuba. It belonged to the farmers and the workers. They all had fought a revolution for democracy, and now it was falling apart.

The Second Front had to go to war again.

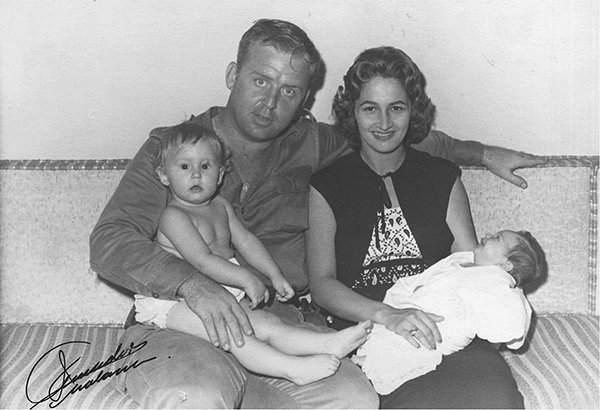

Morgan, Olga, Loretta, and Olguita Courtesy of Morgan Family Collection

For most of the night, the baby had been crying. Olga walked back and forth between the nursery and the bedroom. Ever since arriving home from the hospital, she hadn’t been able to sleep. Morgan had been at the hatchery until late and then came home and met with his men on the balcony.

After an hour, Olga pulled her husband into their room. “No secrets, commander,” she said.

Morgan knew he couldn’t keep anything from Olga. She knew him better than anyone. But still, this wasn’t easy. He told her about the Soviet infiltration in the mountains and what it meant for all of them. They couldn’t stand by and watch Cuba being swept into the Communist vortex. He had tried to live in Cuba in peace. No one knew more than Olga all the work and care he had put into the hatchery to make a stable living.

But everything they had fought for was at stake. There was no way they could compromise with what they had just discovered. They couldn’t stay in their home. They were no longer just raising fish and frogs at the hatchery. They were storing guns there and moving them to the mountains.

“We have to move against them,” he said.

Olga recalled throwing her arms around him. No one wanted to live in peace as much as she did. She was the mother of two children. But she not only understood everything Morgan was saying to her, she completely agreed. They had met in the revolution. They had married in the revolution. If need be, they would die in the revolution.

“I am with you,” Olga said.

Once he got the phone call, Rafael Huguet dashed down to the hatchery. The young pilot who spoke fluent English hadn’t seen the Americano in weeks, but could sense the urgency in Morgan’s voice. The last of the trucks had just left when Huguet showed up, leaving him and Morgan and a few others alone.

Cuban by birth, Huguet had spent much of his life in the United States, attending Georgia Tech and learning his life’s passion to fly airplanes. He had opposed the Batista regime ever since his father was beaten by government police during a routine traffic stop in Havana. On the last day of the revolution, Huguet had copiloted a plane laden with arms into Trinidad with bullets flying into the windows of the craft as it landed.

Out of earshot of the workers, Morgan ushered him past the croaking frogs and into a small room off the side of the main building. Before Huguet could say anything, Morgan walked across the room and opened a closet door. “I want you to see something,” he said.

Inside were stacks of machines guns, automatic rifles, grenades, and boxes of ammunition. Huguet stepped back for a moment, surprised. “William, what are you doing?” he said. “Are you crazy?”

Morgan shut the door. The weapons were there for a reason: He was heading to the mountains. It wasn’t just an idle threat anymore. It had started with hiding weapons near Banao for protection. Trucks had left the hatchery almost weekly. But it had escalated. Castro had crossed a line that the Second Front could not accept. He was inviting Soviet military advisers to the Escambray.

It wouldn’t be easy, but Morgan was prepared to train hundreds of men in the mountains, including the farmers who had become so angry with the government. “We have to do something about this guy,” he said.

The guerrillas had started to get help from the CIA, which had just dropped a cache of weapons from a plane into the foothills. Morgan didn’t want to deal with the agency, but if it was willing to supply weapons, so be it.

The Yanqui comandante was taking an enormous risk by moving weapons. “You are open to too many people,” Huguet said.

Morgan nodded, but he wasn’t going to be dissuaded. It was too late to worry about what Castro was going to do. His reason for calling Huguet was simple: He needed someone in Miami to help procure weapons from anti-Castro activists and if need be to fly them in under the cover of darkness to remote airstrips.

“Would you back me up?” Morgan asked. “Would you get arms for me?”

For Huguet, the timing was right. Once a passionate believer in the revolution, he had grown disillusioned with Castro and others like Che. He had come to admire Morgan over the past two years, not just for what he accomplished during the revolution but what he managed to do after.

Huguet nodded. “I will,” he said.

He would be in Miami in two more weeks and would call Morgan when he arrived. Then they could get started. He would have to make the critical contacts to begin raising arms. But the bigger challenge was whether he could deliver the weapons in time.