On a cold, windswept morning in January 2002, a reporter pulled in front of the worn, shingled townhome at the end of the long, narrow block.

Peering at the windows covered with ice, Michael Sallah (one of the authors of this book) eased into the parking space in front of the house. As the Toledo Blade’s national affairs writer, Sallah had covered stories filled with much of Toledo’s history: the mob, the politicians, the captains of industry. But this one had faded over the decades into barely a footnote, if that.

As he ventured to the front steps, a tiny, hunched-over figure ambled to the door, peeking through the crack. Before the dark, diminutive woman had a chance to say anything, Sallah introduced himself and then, without hesitating, asked the question: “Are you Olga Morgan?”

Olga Morgan. It had been years since anyone called her that name. She was Olga Goodwin. She was remarried—a grandmother—and had been living in obscurity in the working-class neighborhood in West Toledo. Few people, including her current husband, knew the secrets of her past.

She looked at the reporter and nodded. Yes, she said. She was Olga.

Sallah asked if he could come inside to talk, just for a few minutes. He had spent hours poring over frayed newspaper clippings about her, even marveling at her photos as a stunningly beautiful revolutionary in the 1950s. He wanted to know more. But Olga was hesitant. It had been years since she opened up about her other life. Years since she left Cuba on a ratty yellow boat during the Mariel boatlift. Years since she arrived in Toledo on a lonely winter day with just a single suitcase.

As she began to shut the door, Sallah insisted on giving her his card, hoping she would not throw it away.

It would be days before she finally agreed to be interviewed, to actually sit and ruminate over her buried secrets. She opened the door to let the reporter into her house, knowing that she could never shut that door again. With a tape recorder on the table, Olga opened up and slowly and deliberately began talking about events that had been stored in her heart.

She had tried to move on with her new life and her new husband and her new home. But the more she talked to the reporter, the more comfortable she became, and within days, she began revealing details about Morgan and a revolution that she tried to forget.

As she rifled through the old photographs and letters in a box on her living room table, she pulled out a grainy black-and-white photo of her and Morgan standing on a mountain peak, clutching weapons and smiling lovingly into each other’s eyes.

“This,” she said, “sticks in my heart forever.”

Every day she was in prison—nearly eleven years—she thought about their life together, their children.

It was during her first day at Guanabacoa prison that she learned from a jail supervisor that Morgan had been executed days earlier, prompting her to lunge at the man’s throat in a frenzy until the guards pulled her off.

For weeks, she was held in solitary confinement: a pitch-black room with a hole in the floor to relieve herself and a slit in the door where the guards pushed through plates of old, crusty bread and rice. When she lay down to sleep, the rats and insects would scurry over her body.

For a time, she didn’t care what happened.

But after being hauled from one prison to the next and witnessing the brutal conditions, she couldn’t stay quiet. She led hunger strikes and eventually emerged as the leader of a group of inmates known as Las Plantadas—the planted ones. At one point, she was beaten with a rubber baton, the pounding permanently damaging her right eye.

In 1971, the United Nations Commission on Human Rights began looking into the conditions of Cuban prisons, particularly the treatment of political prisoners. To rid itself of the attention, the Cuban government agreed to free some prisoners. Olga’s name was called. At first, she was stunned. She had already been labeled as a troubled inmate and a lifer. But one day in August 1971, she was summoned to the visitors’ room and was met by family members, including her daughters. She was free.

In the ensuing years, she tried to move on with her life. She would walk the streets of Havana, but was constantly reminded of her husband. The pain, sometimes, was worse than what she felt in prison.

One day, she showed up at the Colón Cemetery. She wanted to see his grave. At first, the caretaker hesitated. Someone could be watching. But Olga persisted. “Just for a minute,” she implored.

The man relented, leading her down a walkway, past the ornate headstones of Cuban generals and presidents. In a remote corner of the cemetery, he opened a mausoleum door. “I could lose my life over this,” he said.

There, Olga saw his resting place for the first time. All at once, the reality of his death hit her like never before. She knew she needed to get out.

She remembered what Morgan had told her: If she and their daughters could ever get out of Cuba, they should go to the United States. His mother would take care of them.

In time, she and her parents and children would get that chance: visas to leave Cuba in 1978. One by one, they boarded the plane bound for Miami. But when it was Olga’s turn to board, she was stopped by the guards. There would be no escape for the widow of the Yanqui comandante.

From the tarmac, she watched as the plane with her family took off, never to come back again. One more cruel kick in the gut.

She went to live in a convent in Havana, but couldn’t stand the thought of being separated again from her daughters. Two years later, she was rousted by one of the nuns. There was a crush of people at the Peruvian embassy, all asking for asylum. “You must go,” the nun told her.

Olga grabbed her clothes, hugged the woman, and bolted toward the embassy. The gate was locked, but she managed to climb the fence, with people frantically pulling her over the top to get inside.

After staying for weeks inside the embassy grounds, she was led to a rickety boat at the edge of Mariel Harbor. Her destination: Miami. But after the boat left the shore, the Cuban navy began firing shots into the bow as a cruel joke. Soon, the craft was taking on water. For hours, Olga huddled and prayed with the other passengers until finally she looked up to see a US Coast Guard helicopter drop from the skies to guide the boat to shore in Key West.

Days later, she managed to join her parents and daughters in Miami. But Olga was uneasy. She didn’t want to settle in a place where so many of her countrymen had found refuge. Once again, she was haunted by the words of Morgan: If you ever need anything, my mother will be there for you. With help from Morgan’s old friend, Frank Emmick, Olga boarded a plane bound for Toledo.

As she sat on the plane, Olga didn’t know what to expect. She had heard so much about Loretta from her son, but had never met her.

Stepping up the stairs of the apartment house where Loretta Morgan was living, Olga looked up to see the matronly, silver-haired woman gazing warmly from the open door. Olga leaped up the stairs and hugged her.

For the next several days, the two women were inseparable, sharing stories about the man they both loved. Loretta was now a widow, too. Just three years after she lost her son, Alexander Morgan died. Loretta eventually sold the big house and moved into the tiny apartment just blocks away.

Tragedy struck again in 1963, when Billy Jr. died of a head injury at the age of six under questionable circumstances while living with his mother and stepfather on a US military base in Turkey. Morgan’s daughter, Ann Marie, was married and living in Indiana.

It wasn’t long before Olga made a decision. She sent for her parents and daughters to live with her in Toledo, a place of cold winters and old brick factories. Olga found a job as a social worker, helping migrants find food and shelter. In time, the family blended into their new world.

By the late 1980s, Loretta’s health began to deteriorate and she was moved to a group home. As she lay dying in 1988, she made a request to Olga: Bring William’s remains back to this country and make sure his citizenship is restored. She had never been able to reconcile with the thought of her son’s body entombed in a Havana cemetery.

Olga smiled and nodded her head. No matter how difficult, she couldn’t say no. Not to William’s mother.

In the years that followed, Olga married Jim Goodwin, a blue-collar worker from Mississippi with kind eyes and a gentle smile. They settled in their small townhome in West Toledo, where Olga began to help raise her grandchildren.

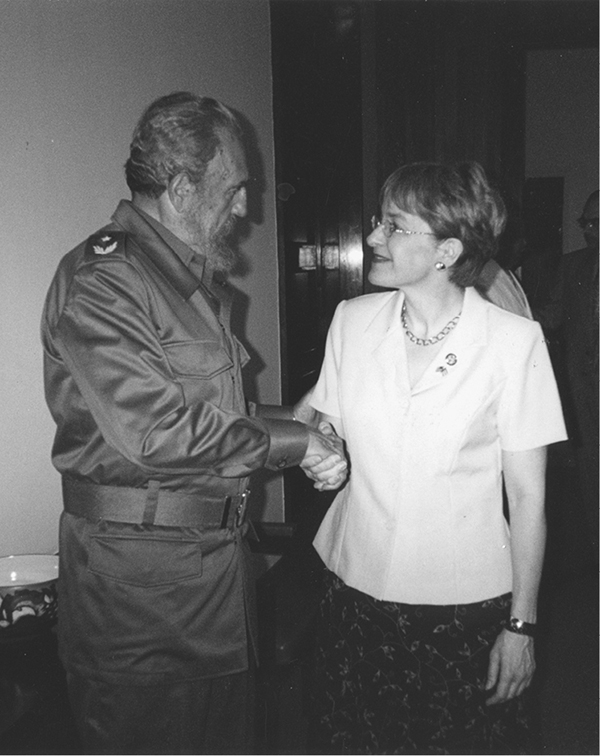

Prompted by a Toledo Blade series, US Representative Marcy Kaptur of Ohio met with Fidel Castro in 2002 to ask that the Cuban government return Morgan’s remains. courtesy of Morgan Family Collection

But it pained her that she had not been able to do anything to carry out her promise to Loretta. One year faded into the next, and William’s body was still in a tomb in Havana. It was during her interview with the Toledo Blade that she brought up the pledge she made years earlier.

Olga didn’t know what to expect when the Blade published its three-part series on the Yanqui comandante in March 2002, recounting Morgan’s remarkable journey to Cuba and eventual death by firing squad. Mitch Weiss (the other author of this book), then the Toledo Blade’s state editor, had reviewed the stories before they ran and remarked that the articles could prompt the US government to act on Olga’s request.

The following month, two members of Congress, Marcy Kaptur of Ohio and Charles Rangel of New York, traveled to Havana to meet with Fidel Castro and begged the question: Would Castro return Morgan’s remains to the United States? After meeting for hours with the lawmakers, Castro said he would consider it.

Meanwhile, a local attorney who read the stories, Opie Rollison, took the liberty to press the US State Department to reinstate Morgan’s citizenship, arguing that the government had no right to strip the Yanqui comandante of his birthright. After two years, the State Department took a rare step in 2007 by reversing its earlier decision and admitting it acted in error nearly fifty years earlier. Morgan was indeed a US citizen.

But the issue over Morgan’s remains is still unresolved. In 2013, US Senator Sherrod Brown of Ohio joined the fight to help bring the body home, meeting with the Cuban Interests Section in Washington, DC. But so far, the plea has not been met.

Olga, now seventy-eight, vows she won’t stop until Morgan is laid to rest in the city where his family is buried. “This was his country,” she said. “This is where he belongs.”

She admits that some days, the task seems impossible. The political tensions between the two countries flare up. Cuba itself struggles with the notion that it would be honoring a ghost from its own difficult past.

When she needs to keep going, Olga turns to a scrapbook in her basement and an old faded letter that Morgan wrote her from La Cabaña in his final hours.

Since the first time I saw you in the mountains until the last time I saw you in prison, you have been my love, my happiness, my companion in life and in my thoughts during my moment of death.

Olga Goodwin in 2012 Courtesy of Morgan Family Collection