2

SOUND—WHAT IS IT?

Understanding the Science of Sound and Why We Use It Therapeutically

You can look at disease as a form of disharmony.

And there’s no organ system in the body that’s not affected by sound and music and

vibration.

MITCHELL GAYNOR, M.D.,

SOUNDS OF HEALING

Before we begin talking about how sound can be used therapeutically, let’s talk a little bit about what it is. There are essentially two definitions of sound listed below. The first one describes vibrations within the range of human hearing, the second vibrations in general.

- Vibrations transmitted through an elastic solid or a liquid or gas, with frequencies in the approximate range of 20 to 20,000 Hz, capable of being detected by human organs of hearing

- Transmitted vibrations of any frequency

For the purpose of our study of sound balancing, we will refer to the second definition.

Frequencies above 20,000 Hertz (abbreviated as Hz) are referred to as ultrasonic, and frequencies below 20 Hz infrasonic. Hertz refers to cycles per second, a term named after the German physicist Heinrich Hertz (1857–1894), who made important contributions to the study of electromagnetism. For example, a 500-Hz tuning fork oscillates 500 times per second.

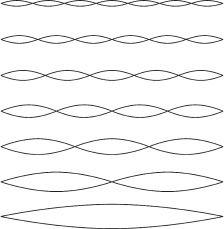

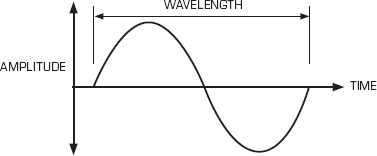

Frequencies produce overtones, or harmonics. A harmonic frequency is a multiple of a fundamental frequency. A fundamental frequency of 500 Hz has a first harmonic frequency of 1000 Hz (2f), double the fundamental frequency. Its second harmonic is 1500 Hz (3f), the third harmonic is 2000 Hz (4f), and so on. A musical instrument produces both fundamental tones and overtones. Technically, every tone produces infinite overtones, although we only hear the first few, a concept illustrated in figure 2.1. When we think about sound waves, we tend to think about them as depicted in the image in figure 2.2.

Figure 2.1. Overtones

Figure 2.2. Wavelength

Figure 2.2 is the classic sine wave depiction. But in reality sound propagates spherically from its source and may travel in spiraling three-dimensional shapes. To this end I recently came across the following mind-bending description:

For example, sound is not a vibration of the air. A sound wave, we know today, is an electromagnetic process involving the rapid assembly and disassembly of geometrical configurations of molecules. In modern physics this kind of self-organizing process is known as a “soliton.” Although much more detailed experimental work needs to be done, we know in principle that different frequencies of coherent solitons correspond to distinct geometries on the microscopic or quantum level of organization of the process. This was already indicated by the work of Helmholtz’s contemporary, Bernhard Riemann, who refuted most of the acoustic doctrines of Helmholtz in his 1859 paper on acoustical shock waves.1

In other words rather than just the pressure wave front that we might tend to think of when we think of sound traveling (the two-dimensional sine wave that most visual depictions show), sound may actually be a complex geometric pattern moving through whatever medium it is traversing. If you have ever seen images in a cymatics video—especially those created by a CymaScope, which is a laboratory instrument that makes visible the inherent geometries within sound and music—this concept makes sense.

CYMATICS

Cymatics is the study of sound and vibration made visible through a medium such as water in a dish, or a Chladni plate, a flat metal plate on which a medium such as salt is placed, with a speaker underneath. As the frequencies delivered through the speaker change, the geometric images produced by the frequencies also change, spontaneously and even somewhat startlingly. The higher the frequencies, the more complex the geometry produced.

The first time I saw the classic cymatics video by Hans Jenny, a Swiss medical doctor and pioneer in this field, I was stunned. I had heard the notion that “the sound current underlies all of creation,” but I didn’t really understand what that meant until I saw these geometric patterns appear and then disappear and then reappear completely differently in response to the sound being produced. There is one scene in particular where some iron filings resembling people dancing suddenly collapse, lifeless, when the sound is stopped, like marionettes whose strings have been cut. I highly recommend going to YouTube and looking at a variety of cymatics videos to experience this directly because it really opens your eyes (and ears) to this fascinating phenomenon.

When we see how sound affects substances, it then makes perfect sense why people practice mantras. Humans being mostly water, any sound we produce reverberates through us, affecting all the structures in our bodies. From the tone of our voice to the words we speak and the sentiment with which we say them, the sounds we make produce a continuous creative structuring in our bodies. If you have seen Dr. Masuru Emoto’s work with ice crystals, as depicted in his book The Hidden Messages in Water, you can see, in crystallized forms, the effects of the difference between beneficial and nonbeneficial words and intonations and how that hypothetically translates to the water in our own bodies.

Sound travels through air at approximately 350 meters per second, and through water at approximately 1500 meters per second, but this depends on many factors, including humidity and temperature. The warmer and more humid the air, the faster sound will travel through it. Generally, the denser the medium, the faster sound travels through it. For example, you can hear a train coming much sooner if you put your ear to the metal track as opposed to just listening to the air current.

COHERENT VS. INCOHERENT FREQUENCIES

Coherent is a word we use a lot in sound balancing. Here’s Webster’s definition:

- Logically or aesthetically ordered or integrated; consistent: coherent style; a coherent argument; having clarity or intelligibility; understandable: a coherent person; a coherent passage

- Having the quality of holding together or cohering; cohesive, coordinated: a coherent plan for action

- Relating to or composed of waves having a constant difference in phase: coherent light; producing coherent light: a coherent source

So, a coherent frequency is one that is ordered, consistent, clear, and in phase. In phase means “operating at the same frequency or wavelength.” An incoherent frequency is disordered, inconsistent, not clear, and out of phase (we all know people who are coherent vs. incoherent). A tuning fork produces a coherent frequency, and that is why it is useful as a healing tool.

Research at the Institute of HeartMath has found that the heart produces either coherent or incoherent frequency patterns based on the emotions a person is feeling. Feelings of love, appreciation, and gratitude cause the heart to produce coherent frequencies, whereas frustration, anger, and other so-called negative emotions cause the heart to produce incoherent frequencies.

I have had direct experience of a HeartMath technology, a simple device that measures and shows the degree of coherence produced by what is called our heart rate variability. HeartMath was one of the exhibitors at a conference I attended a few years ago, and I was interested to see if their technology could be useful as a biomarker measurement in my research. I sat down at the table and got hooked up to the device, a little sensor that attached to my ear, and began to chat with the representative about my research. The output on the computer screen looked like a stock market chart: it was irregular and jagged. The representative then had me think about something that gave me loving feelings, and so I mentally recalled saying good-bye to my boys before I headed out on my trip. I had to wake them up at 4 a.m. to say good-bye, and they were all sleepy and cute. As my heart swelled with this memory, the readout suddenly changed to show an orderly and balanced sine wave.

This is such a beautiful and elegant tool to show people what a difference their thoughts and feelings make regarding their health. When you consider that the heart is the driving rhythm for the entire body, and as we will see later, how every cell is bathed in its electromagnetic field, its “mood” affects the well-being of every organ and system in the body.

So, not only are we affected by the degree of coherence vs. incoherence in our inner environment, we are also affected by our outer environment.

NOISE

As I sit at my kitchen table writing this page, I am listening to my refrigerator. It is making a few different sounds: a kind of a low rumble, and then this fluctuating wrr WRRR wrrr WRR sound on top of that. Truly, it sounds terrible, and when I focus on it I realize that I have tension in my neck and shoulders that is bracing me against it.

I also have two fluorescent lights in the kitchen that make noise. Sometimes, if I am busy, I don’t notice them, but other times I become quite aware when they are on and notice that they are making me irritable.

I once owned a restaurant, and when I worked in the kitchen there were many different noises going on all the time—the compressors in all the refrigeration units, the overhead lights, the sizzling food, the din of customer’s voices, the music playing, the dishwasher running. Every once in a while, the power would go out and everything would suddenly fall silent. I always noticed that I let out a big sigh and dropped my shoulders whenever this happened. All this noise was a constant low-level stressor on my body that created muscular tension and subsequent lack of energy flow in my body. Chronic tension leads to chronic fatigue and other disorders.

The unfortunate fact of the matter is that most mechanical and electrical engines are built with little consideration as to the quality of sounds they emit as a consequence (think leaf blowers). With the exception of nuclear submarine engines and other high-performance machines, most things that run make dissonant and stressful sounds. Our modern world is so full of noise, both in our homes and outside, in such a broad spectrum of frequencies, that it is a wonder that any of us are sane or healthy. We are constantly beaten down by the chaos that surrounds us as our bodies struggle to retain the inner harmony dictated by our “factory settings,” our prime frequencies.

The scientific study of the propagation, absorption, and reflection of sound waves is called acoustics. Noise is a term often used to refer to an unwanted sound. In science and engineering, noise is an undesirable component that obscures a wanted signal.

What, then, is the wanted signal? Mostly what people seem to crave as wanted signals are sounds of nature. Away from the constant din of civilization, we find restoration in nature—at the ocean, with the crashing of the waves, in the forest next to a brook’s waterfall, at the top of a mountain enjoying the silence. These kinds of sounds are often incorporated into healing music, but right now there is a growing field of practitioners and clients who are discovering the power of pure acoustic tones, through the use of gongs, Tibetan and crystal singing bowls, native drums, and other acoustic instruments.

WHY USE SOUND THERAPEUTICALLY?

The human body is wired to be exquisitely sensitive to sound. The faculty of hearing is one of the first senses to develop in utero and the last to depart before death. In addition to perceiving sound through our ears, we also “hear” the pressure waves of sound through our skin, and the water that makes up approximately 70 percent of us conducts sound four to five times faster than air.

Our bones also conduct sound, as evidenced by newer hearing aids that conduct sound through the skull directly to the cochlea, and through the technique of using a vibrating tuning fork to determine if a bone is fractured. In this technique the tuning fork is placed distal to the suspected fracture and the stethoscope is placed proximal to the injury on the same bone. A clear tone indicates an uninjured bone, whereas if the sound is diminished or absent, it indicates the presence of a fracture.2

It has been discovered that in addition to the traditionally viewed lock-and-key structure of receptors on cell membranes that receive and respond to physical molecules, there are also antenna-like structures (i.e., primary cilium) that respond to vibrational frequencies. Biologist Bruce Lipton writes in The Biology of Belief:

Receptor antennas can also read vibrational energy fields such as light, sound, and radio frequencies. The antennas on these energy receptors vibrate like tuning forks. If an energy vibration in the environment resonates with a receptor’s antenna, it will alter the protein’s charge, causing the receptor to change shape. Because these receptors can read energy fields, the notion that only physical molecules can impact cell physiology is outmoded. Biological behavior can be controlled by invisible forces as well as it can be controlled by physical molecules like penicillin, a fact that provides the scientific underpinning for pharmaceutical-free energy medicine.3

When I first came across this passage, I had to sit and look out the window for a long time. Here was an explanation for what I had been observing for years with my tuning forks, without really understanding what was going on: teeny reciprocal tuning forks on each cell membrane, producing either incoherent or coherent frequencies, “changing their tune,” as it were, when bathed in coherent sound.

This also struck me as potentially a biological mechanism of what we call intuition. We all sense “vibes” coming from other people, but how do we sense them? The thought of little antennas on our cells picking up ambient frequencies explains this perfectly. One of my students, a sixteenyear-old girl, told us about a wilderness program she had attended where one of their exercises was to walk blindfolded through the forest while some of their fellow students hid and broadcast ill intentions. The process was designed to sensitize the students to pick up on these frequencies.

This is how all of nature operates, by paying attention to these kinds of signals. Any of us who have pets know that pets can read our vibes without having to use words. And research into plants has shown that they too can read our vibes. In The Secret Life of Plants, author Peter Tompkins recounts how he hooks some plants up to a polygraph machine and discovers, among many other interesting things, that the plants register alarm when he has the intention of burning them with matches.

I had a memorable experience last summer with tuning forks and plants hooked up to a polygraph machine (no matches were involved). I was visiting some friends in Colorado, and we went to visit one of their friends, Luiz, who was conducting Ph.D. research at the University of Colorado in a manner similar to the work of Tompkins. He had two different plants in his lab, attached by thin metal probes to a polygraph system in his computer. We wanted to see how the plants would respond to “getting a tune-up.”

I began, like I do with my clients, by locating the edge of the field, which was about 2.5 feet away from the plant itself, slowly working my way in toward it. Almost immediately, the polygraph readout began to edge downward. “That means the plant is relaxing,” Luiz told me. The readout continued its downward descent as I moved in closer and closer to the plant. And then a curious thing happened. In sound balancing there is a lightening or brightening of the tone once the work on any given chakra is complete—a sort of release of the process. I sensed this happening with the plant, but then returned with another strike of the fork anyway, and immediately the readout began to edge back upward. The plant seemed to know its treatment was complete and began to resist my continued advances.

The next plant provided another very curious experience. While the first one was an Amazonian medicinal plant, this second plant was just a regular ornamental bamboo house plant. As I approached it with the fork, the readout on the computer hardly changed at all; if anything, it edged upward slightly, and what I encountered was something that I absolutely had not anticipated: the fork was reflecting in its overtones the frequency signature that I have come to recognize in people as fear, with a pulsing quality to the sound. It appeared that the poor plant was afraid of me! I said this to Luiz, and he replied, “It is interesting that you say that because I actually had a very good psychic here last week, a woman who works with the Colorado State Police, and she also told me that the plant was afraid.” The implications of this were profound—it appeared that there was a common emotional vibrational language not just among people and animals, but with flora as well. This explained how and why Tompkin’s plants sensed his intention to harm them. It also made me think of how we say “dogs smell fear,” and while they no doubt do, they also sense fear, along with every other vibrational emotion we are emitting, because we all speak the same language on the level of our vibes.

Before we go much further exploring how and why sound works on the body, let’s answer a question that I am often asked: How did I get into sound in the first place?