INTRODUCTION: THE ‘DARK ANGEL’ OF THE 1950S

In Bettie Being Bad, his comic-book homage to Bettie Page, the 1950s pin-up queen, American artist John Workman celebrates the icon’s cult cachet. For Workman, Bettie Page offered a walk on the wild side. Against a tide of bland conventionality, he argues, Page lined up in an army of cultural outlaws who refused to toe the conformist line and instead cocked a defiant snook at the compliant, conservative world of ‘the squares’. Or, as Workman puts it:

In the 1950s, they had Ozzie and Harriet, Davy Crockett and Doris Day. We had Lenny Bruce, E.C. comics and BETTIE PAGE!1

During the 1950s the image of Bettie Page graced the covers of myriad American men’s magazines. Starting her career as a model for amateur camera clubs, Page found fame amid the mid-century boom in pin-up magazine publishing, her trademark raven black hairstyle and beguiling smile captivating a legion of admirers. Tame by modern-day standards, Page’s pin-ups were what the publishing industry called ‘cheesecake’ – photo-spreads of seductively posed (often semi-nude) pretty girls who delighted readers through their winning looks and buxom charms. By the mid-1950s Page had cornered the ‘cheesecake’ market and was omnipresent across the gamut of American men’s magazines, appearing especially regularly in Robert Harrison’s stable of pin-up titles, as well as innumerable film loops and photo-sessions produced by the New York ‘Pin-up King’, Irving Klaw.

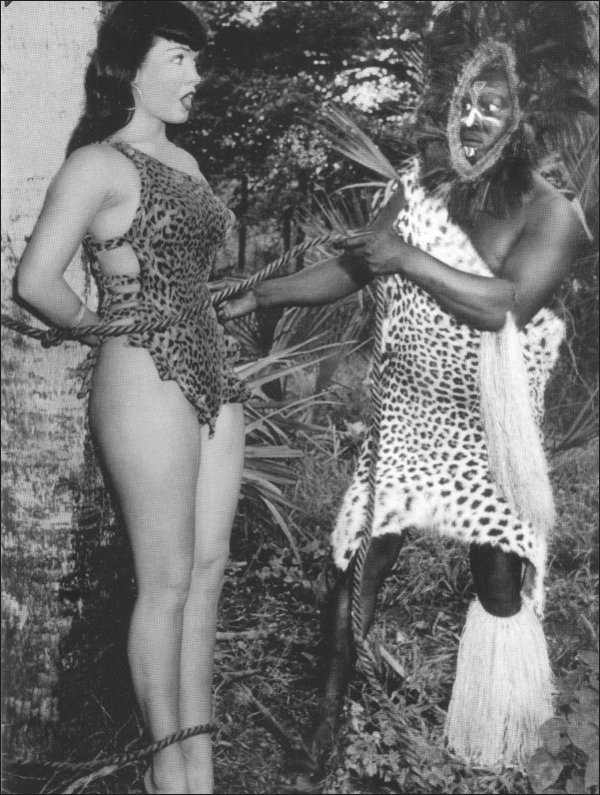

FIGURE 1.1 Bettie Page: the ‘Dark Angel’ of 1950s America

But Bettie Page’s other work with Klaw also helped establish her more infamous reputation as the ‘Dark Angel’ of the 1950s. Page appeared in scores of Klaw’s short films featuring fetish vignettes (depicting ‘cat-fights’, spanking and elaborate bondage sessions), as well as sadomasochistic photo-shoots where Page posed in improbably high-heeled stiletto boots, leather corsets and long-sleeved leather gloves, sometimes brandishing a whip or trussed-up in ropes, chains and a ball-gag.

The sexual dynamics of this facet to Page’s career, however, were always shot-through with polysemic ambiguity. As Maria Buszek argues, rather than being simple exercises in misogyny, the sheer theatricality of Page’s bondage routines can be read as a pantomime of transgressive parody that roguishly revealed the constructed, performative nature of sexual roles and identities:

Even in the … more extreme, intricately constructed bondage scenarios, Page’s participation and performativity shine through as she manages absolutely comical body language through ominous looking binding and ball-gags. Not only does such imagery expose the control and playfulness that Page exerted in her pin-ups, to this day such imagery is held up by many S-M [Sado-Masochism] and B-D [Bondage-Domination] practitioners as exemplary of their belief in role-playing and consent.2

Part of Bettie Page’s cult appeal, therefore, lies in the way her bondage scenes were characterised by a complex plurality that encompassed elements of frisk theatricality. But the way Page oscillated between her ‘good girl’ and ‘bad girl’ imagery is also important. The two sides to Bettie Page’s modelling career make her an enthralling character who has become symbolic of the processes of flux and fragmentation endemic to American public and private life throughout the postwar era. While Page’s ‘cheesecake’ photo-features connoted a bold and buoyant age of playful open-mindedness, her bondage and fetish work was both darker and more mischievous – pointing a sardonic finger at the insecurities and fears lurking behind the confident façade of 1950s America. And it is this plurality and wealth of contradictions that have sustained Bettie Page’s cult status. Indeed, since the 1980s a Bettie Page ‘revival’ has seen the pin-up star enshrined as a popular cultural icon in two biopic movies (Bettie Page: Dark Angel (2004) and The Notorious Bettie Page (2006)), as well as a host of DVD re-releases, comics, fanzines and all manner of popular kitsch. This continuing fascination is indebted to the way Bettie Page functions as a signifier for the tensions of 1950s America, her image combining both the public face of upbeat sparkle and the more private world of guilty secrets.

FIGURE 1.2 Bettie Page as pin-up icon

Born in Nashville, Tennessee in 1923, Bettie Page (many 1950s magazines misspelled her name as ‘Betty’) grew up in itinerant poverty. Her father, a womanising drunkard, wandered the Depression-hit South in search of work and, after her parents divorced, Bettie spent some time living in an orphanage before settling with her five brothers and sisters and disciplinarian mother. Despite a tough childhood, Page was a hardworking student and, with hopes of becoming a teacher, won a college scholarship and graduated with a degree in Education. Marrying a sailor in 1943, she got a job as a secretary but, after divorcing four years later, she moved to California with the dream of becoming an actress. Modelling work came her way but, despite a handful of screen tests with major studios, a Hollywood career never materialised. Disappointed, Page moved to New York in 1950 and picked up more modelling and secretarial work.3 But things were soon to change.

Wandering along Coney Island beach in autumn 1950, Page got talking with Jerry Tibbs, a black Brooklyn cop and keen amateur photographer. Struck by Page’s looks, Tibbs offered to make her up a portfolio of photographs to hawk around studios and photographers if she agreed to pose for him. The two struck up a friendship, and it was Tibbs who persuaded Page to adopt her trademark hairstyle, suggesting she swap her run-of-the-mill ponytail for a curved fringe (known as ‘bangs’ in America) that would became famous as the classic Bettie Page ‘look’. Through Tibbs and other photographer contacts, Page quickly found work posing on the amateur and semi-professional camera club circuit that had sprung up in America during the 1940s. Ostensibly existing to promote ‘artistic’ photography, many ‘camera clubs’ served as a means of circumventing legal restrictions on the production of nude photos, and Page regularly posed for local clubs on weekend photo jaunts to upstate New York and rural New Jersey.

Page also attracted the attention of pin-up mogul Robert Harrison. During World War II, American pin-up magazines had prospered, partly as a consequence of a general loosening of sexual morality and partly as a result of a burgeoning market among libidinous servicemen.4 Harrison had quickly capitalised on the opportunity, launching his first pin-up title, Beauty Parade, in 1941 and repeating its success with a series of clones – Eyeful (launched in 1942), Wink (1945), Whisper (1946), Titter (1946) and Flirt (1947)

During the early 1950s the pin-up boom continued. Harrison’s attentions, however, were increasingly focusing on the runaway success of his muckraking scandal sheet, Confidential (launched in 1952), but his pin-up titles were still a big earner and in 1951 Bettie Page began gracing their covers and photo-spreads on a regular basis.

In many respects it is easy to see the covers and pictorials of magazines such as Beauty Parade and Eyeful as the embodiment of an oppressive and objectifying ‘male gaze’. But, as Stuart Hall has famously argued, popular culture is invariably an arena characterised by ‘the double movement of containment and resistance’.5 And, in these terms, it is possible to situate Harrison’s pin-up magazines in the long, seditious heritage of American burlesque.

As Robert Allen shows, during the mid-nineteenth century a tradition of theatrical burlesque won popular success through its mixture of impertinent humour and provocative displays of female sensuality. For Allen, burlesque was culturally subversive because it was ‘a physical and ideological inversion of the Victorian ideal of femininity’.6 The scantilyclad burlesque performer, Allen suggests, was a rebellious and self-aware ‘sexual other’ who transgressed norms of ‘proper’ feminine behaviour and appearance by ‘revel[ing] in the display of the female body as a sexed and sensuous object’.7 But, Allen argues, while burlesque initially played to a respectable, middle-class audience, it was quickly relegated to the shadow-world of working-class male leisure. And, in the process, the burlesque performer steadily ‘lost’ her voice. As burlesque increasingly revolved around the display of the performer’s body, Allen contends, ‘her transgressive power was circumscribed by her construction as an exotic other removed from the world of ordinary women’.8

Allen’s account, however, is too hasty in announcing the demise of burlesque’s subversive potential. During the 1950s, for example, echoes of burlesque’s tradition of transgression still reverberated through American popular culture. For instance, while Robert Harrison’s pinup magazines certainly presented pin-up models as sexual objects, they also featured marked elements of camp humour and playful satire. Many of Harrison’s photo-spreads, for example, featured models acting out spoof scenarios in elaborate ‘comic book’-style photo stories whose tongue-in-cheek silliness effectively elaborated a self-parody of the whole pin-up genre. ‘Gal and a Gorilla’, for instance, saw Bettie Page zipping around New York with her ‘constant escort’, the scooter-riding Gus – a man dressed in a ludicrous gorilla costume.9

And the burlesque resonated through many other aspects of Bettie Page’s career. Her work with photographer Bunny Yaeger, for instance, undoubtedly traded on Page’s knockout looks, but it was also marked by a knowing sense of irony. Yaeger had, herself, been a successful pin-up model and was trying to get her foot in the door as a photographer when she teamed up with Page in 1954. In Florida the pair spent a month working on some of Page’s most successful photo-shoots. One of the most famous was the ‘Jungle Bettie’ session that took place at the USA Africa Wildlife Park. Clad in a spectacular leopard-skin outfit (that, like most of her costumes, she had made herself), Page posed with a pair of leashed cheetahs, swung like Tarzan from lush mango trees and was captured by a tribe of cannibals in a series of photographs that at once both celebrated and playfully lampooned stock stereotypes of the ‘exotic Amazon’.

Another light-hearted Yaeger shoot saw Bettie posing nude, aside from a jolly Santa Claus hat and a cheeky wink given to the camera – an image that was quickly snapped up by Hugh Hefner and used as the centrefold to the January 1955 edition of his flourishing Playboy magazine.

Burlesque traits also surfaced in Page’s work with Irving Klaw. It was through her work with Robert Harrison that Page first got to know Klaw and his sister Paula. The Klaws had started in business during the 1930s, running a second-hand bookstore in Manhattan, with a sideline in mail order magic tricks. Neither trade was exactly a money-spinner. But in 1941 they struck lucky when Irving noticed his customers’ annoying habit of ripping-out pictures of movie stars from his magazine stock. Spotting a market opportunity, the Klaws went into business selling movie posters and publicity stills. Abandoning the magic tricks, they set up a new company – Movie Star News – and did a brisk trade in mail order sales of movie material. During the war the Klaws enjoyed a lucrative turnover selling pictures of Rita Hayworth and Betty Grable to GIs posted overseas, but during the 1950s they moved into producing their own pin-ups of hired models, working with Bettie Page for the first time in 1952.10 But, as well as the photo-shoots, Irving Klaw also had big screen ambitions.

FIGURE 1.3 ‘Jungle Bettie’: stereotypes of sexuality and race are parodied in Page’s work with Bunny Yaeger

FIGURE 1.4 Burlesque goes celluloid: Bettie Page in the influential Teaserama

Klaw, however, was beaten to the post by Martin Lewis. A New York cinema owner and part-time film producer, Lewis hired Page to act in his black-and-white ‘B’-movie burlesque review, Striporama (1952). The movie’s loose plot saw three hapless comics convince the ‘New York Council for Culture’ that burlesque was a national institution by staging a show whose acts included Bettie Page in a bubble-bath scene staged in a Sheik’s harem, alongside a routine (billed as ‘Rosetta and Her Well-Trained Pigeons’) where a talented flock of birds make off with a performer’s clothes. Despite its threadbare production values, Striporama was a hit, making around $80,000 within nine weeks of its release, a success that spurred Irving Klaw to sign Page up for movies of his own.

Klaw had already shot Page in a few 8mm and 16mm film shorts, but he began thinking bigger and soon included her in two feature-length films, Varitease (1954) and Teaserama (1955). Shot in Eastman Color, both abandoned conventional narrative, and instead comprised sequences of various burlesque routines. The main attraction of Varitease was the established burlesque star Lili St. Cyr, but Bettie Page also got high billing for her appearance as a sequined harem girl performing an over-the-top version of the ‘Dance of the Seven Veils’. Teaserama saw Page in a more central role, wearing a variety of campy costumes to introduce the acts and appearing in a black, silk maid’s outfit in a routine alongside burlesque luminary Tempest Storm.

According to Allen, the wave of 1950s burlesque films of which Varitease and Teaserama were a part can be seen as exemplifying a sexist scopic regime of the kind identified by Laura Mulvey in her renowned 1975 essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’.11 In these terms, texts are seen as constructing women as the sexual objects of masculine pleasure. And, indeed, burlesque performers such as Bettie Page, Lili St. Cyr and Tempest Storm were certainly ‘objects’ of a gaze. But, as Eric Schaefer points out, the burlesque genre is open to a much broader range of readings than simply that offered by Mulvey’s notion of male visual pleasure.12 According to Schaefer, the burlesque striptease films of the 1950s had the potential to be socially transgressive in much the same way as the nineteenth-century shows championed by Allen. As he explains, by removing her clothing in a highly ritualised and stylised way, the 1950s burlesque performer not only became a potential object of erotic desire, but in making a spectacle of herself

she simultaneously made a spectacle of gender identity. As performers, strippers were not merely the bearers of meaning in films, but active makers of meaning, calling attention to the performative aspect of gender.13

And these elements of burlesque transgression, inherent in many facets of Bettie Page’s career, raise interesting questions about the way 1950s America should be understood. According to many historians, American society during the Cold War was characterised by a deep suspicion of dissension and stern pressures to conform. From this perspective, US foreign policies geared to the ‘containment’ of communist influence abroad found their parallel at home. Alan Nadel, for example, argues that America’s cultural agenda during the 1950s was infused by paradigms of containment, with literature, cinema and the spectrum of popular culture deploying narratives that ‘functioned to foreclose dissent, pre-empt dialogue and preclude contradiction’.14

At the heart of these ideologies of containment stood archetypal images of straight-laced, suburban domesticity. As Elaine Tyler May shows, family life was configured as a vision of reassuring certainty in an unpredictable and threatening world. As the superpowers squared up, pressures for social stability intensified and nonconformity – whether configured in political, cultural or sexual terms – was increasingly perceived as a threat to American security. Amid this ambience of anxiety and distrust, May argues, strategies of ‘domestic containment’ promoted domesticity and ‘normal’ family life as fundamental to the strength and vitality of the nation – and any deviation from these norms risked charges of abnormality and deviance.15

Certainly, there is a lot of truth to this depiction of 1950s America. The McCarthyite witch-hunts, for example, may have been geared to ferreting out ‘reds under the bed’, but John D’Emilio16 and David Johnson17 both show how they were also a ‘lavender scare’ that conflated red-baiting with rabid homophobia. Representations of contented family life, meanwhile, were undoubtedly ubiquitous in American culture throughout the 1950s. Academics, politicians and the mass media all championed the family as both the cornerstone of American liberty and as a panacea to the perceived social and sexual dangers of the day. In magazines like Life, depictions of the middle-class family embodied a confident sense of national identity,18 while television series such as Ozzie and Harriet (1952–66), Father Knows Best (1954–63) and Leave It to Beaver (1957–63) all presented an idealised family life of cheerful tranquillity.

Nevertheless, just as American foreign policy failed to ‘contain’ communist influence abroad, ‘domestic containment’ failed to exercise an iron grip over cultural life at home. Indeed, the sheer amount of effort invested in pressing down the lid of ‘containment’ suggests that many people were embracing cultural values sharply at odds with traditional gender roles and dominant ideals of family-oriented domesticity. Indeed, contrary to popular perceptions of the 1950s as a time of relative tranquillity and consensus, historians have increasingly shown the decade to be ‘an era of conflict and contradiction, an era in which a complex set of ideologies contended for public allegiance’.19 Authors such as Larry May20 and Joel Foreman,21 for instance, have highlighted the dimensions of disruption and dissent that distinguished the decade. From this perspective, the attention accorded to the authoritarian discourses of the 1950s has enriched our understanding of the era, but it has also

contributed to an imbalanced view that so amplifies the effect of socio-political coercions that the substantial manifestations of dissent and resistance disappear into an easily overlooked background. To one degree or another, most studies of the 1950s are affected by this disposition and thus appear as histories of victimization rather than histories of nascent rebellion and liberation.22

This is especially true with regard to constructions of femininity. Betty Friedan’s 1963 bestseller, The Feminine Mystique,23 has left an enduring image of women in 1950s America as the suffocated victims of a ‘comfortable concentration camp’, with the claustrophobia of suburban drudgery generating feelings of confusion, self-doubt and despair. Yet Joanne Meyerowitz24 incisively shows how femininity and its cultural representations were much more diverse than allowed for in accounts such as Friedan’s. Alongside conservative visions of submissive domesticity, Meyerowitz demonstrates how there also existed many representations of women as independent, creative and non-conformist. And, while it is folly to cast Bettie Page as any kind of figurehead for 1950s feminism, the prevalence of her image across the panoply of American popular culture certainly flipped an irreverent middle-finger to the nation’s puritanical moral guardians. More importantly, Page’s traits of burlesque parody and pastiche served to reveal the artificiality and performativity of gender identities. And, while these elements were always a significant facet to her ‘Good Bettie’ cheesecake pin-ups, they were even more pronounced in her ‘Bad Bettie’ bondage work.

THE DELIGHTS OF DISCIPLINE

Irving and Paula Klaw’s movie stills and pin-up business thrived, but they found some customers, especially those from the higher end of the social scale – doctors, lawyers, businessmen – often asked for more specialised ‘Damsel in Distress’ photos, where models were bound, gagged and roundly spanked by a leather-clad dominatrix.

Never ones to miss a market opportunity, the Klaws were happy to oblige. With hired models and a stockpile of lingerie, fetish costumes and props, the Klaws began producing photos and short film loops featuring elaborate scenarios of bondage and domination, with Irving directing and Paula taking many of the photos.25 The images dealt with the outré, the taboo and the outright kinky but, because the Klaws were desperate to avoid charges of peddling pornography, nudity was strictly verboten. Indeed, it was not uncommon for Irving to insist that models wore two pairs of knickers, lest an unruly tuft of pubic hair creep into shot.

Throughout the early 1950s Bettie Page was one of the Klaws’ most popular bondage models. Alongside her camera club and men’s magazine modeling, she regularly worked with the Klaws on short bondage films and photo-shoots. Jungle Girl Tied to Trees, for example, saw Page dressed in a leopard-skin bikini and roped between two trees, being menaced by a woman wearing a leather skirt and high heels and wielding a huge bull-whip. Betty Gets Bound and Kidnapped, meanwhile, found Page drugged, abducted and trussed up in her underwear by two wicked dominatrices. Some customer requests were particularly bizarre. As Page recalled with a chuckle in one of her rare interviews, ‘the wildest request’ she ever had was

when this guy sent in a pony outfit with a hood, covered in black leather. And I had to get down on my feet and hands like a pony, and Paula put this costume over me. You couldn’t even see my face, but that’s what this guy wanted.26

FIGURE 1.5 Creating a bondage icon: Irving Klaw and Bettie Page

For the customer, these convoluted bondage scenarios were obviously a source of illicit sexual thrills. But there were also other, possibly more renegade, meanings at stake. Like the burlesque qualities inherent in Page’s pin-ups, her bondage work can be seen as highlighting the perfomativity of gender roles and sexual identities. According to the influential work of Judith Butler, gender is not a stable entity or an ‘agency from which various acts follow’, rather it is ‘an identity tenuously constituted in time, instituted in an exterior space through a stylized repetition of acts’.27 In these terms, gender can be understood as a shifting set of ‘performances’ – a ‘corporeal style’ that is fabricated and sustained through a set of performative acts and ‘a ritualized repetition of conventions’.28 For Maria Buszek, Bettie Page’s bondage work with the Klaws is a case in point. Oscillating between the virgin and the vamp, she argues, Page helped ‘maintain the presence of the complex, pluralistic pin-up in an era that vigorously sought to use the genre to communicate far more binary – and therefore stable – constructions of female sexuality’.29 Particularly significant is the plurality of roles Page assumes in the bondage shots. Rather than being exclusively dominant or solely submissive, she switches between the two, taking on each theatrical performance with an over-the-top gusto – whether snarling with cartoonish menace as the ‘spanker’, or wincing with indignation as the helpless ‘spankee’.

THE DARK ANGEL’S DOWNFALL

Throughout the 1950s the terrain of sexual politics was continuously contested and contradictory. But authoritarian ‘containment’ was always a force to be reckoned with. By 1955 Joseph McCarthy’s political witch-hunts had run out of steam, but Estes Kefauver’s cultural crusade was just getting in its stride. In 1951 Kefauver, the Democratic Senator for Tennessee, made his mark as head of a Senate investigation into organised crime. Four years later he set his sights on another spectre that ostensibly menaced postwar America – juvenile delinquency. Appointed in 1953, the Senate Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency had already been underway for two years when Kefauver assumed its chairmanship, but under his direction the proceedings gained energy and gravitas.

Televised from gavel-to-gavel, the Subcommittee considered a range of potential causes of juvenile crime, but they were preoccupied with the possible influence of the media. Throughout the mid-1950s the Senators heard testimony from a parade of experts and moral crusaders such as the psychologist Frederic Wertham, who cited the media’s proclivity for violence as having a woeful impact on the nation’s youth. While the clamour for tighter federal censorship was resisted, the Subcommittee demanded that the media exercise stricter self-regulation – a call that prompted the Comics Magazine Association to pass its infamous Comics Code in 1954, effectively outlawing the horror and crime comics beloved by rebellious youngsters. Having smashed horror comics, Kefauver turned his attention to pornography. In 1955 he came to New York looking for scalps, and Irving Klaw was high on his hit-list.

Though he struggled hard, Kefauver could never prove a link between pornography and juvenile delinquency. But the Klaws and Page were subpoenaed to appear before his Subcommittee. Ultimately, Page was not called to testify, but Irving Klaw was hauled-up for a fierce grilling. Kefauver bent over backwards to paint Klaw as a kingpin of American porn and an arch-corruptor of the nation’s youth, but Klaw resolutely denied that he dealt in obscene material (his films, after all, featured no nudity) and he defiantly ‘took the fifth’, refusing to co-operate with the investigation.

FIGURE 1.6 Bettie as ‘Spanker’ and ‘Spankee’: modes of gender performance in her work with Irving Klaw

At the end of the day, Kefauver got nowhere. His Subcommittee’s work finally sputtered out in a 1960 report, Control of Obscene Material, which was largely ignored by federal and state legislators alike.30 But the hearings effectively broke the Klaws. In the face of bad publicity and FBI harassment, Irving feared prosecution and closed down his business in 1957. Burning most of his pin-up and bondage negatives (though some were luckily saved by Paula), he retired to Florida. The Kefauver hearings also had a traumatic impact on Bettie Page. In 1957 she quit New York and never returned to the big city or her modelling career. As her personal life became increasingly unstable, she drifted through a series of failed relationships and succumbed to the ravages of alcoholism, mental illness and, perhaps even worse, evangelical Christianity.

BETTIE PAGE REBORN

Vanishing from the public eye enhanced Bettie Page’s aura of mystique, and by the late 1970s a cult interest in the model had begun to cohere. During the 1970s and 1980s a series of books appeared featuring assorted photos of Page from the 1950s, presenting them as a ‘nostalgic’ look at the erotica of days gone by. In 1976, for example, Eros published A Nostalgic Look at Bettie Page, while Belier Press launched four volumes of Betty Page: Private Peeks between 1978 and 1980; and in 1983 London Enterprises released In Praise of Bettie Page: A Nostalgic Collector’s Item, reprinting a series of camera club photos and a ‘cat-fight’ photo-shoot. In 1987, meanwhile, Greg Theakstone started the fanzine The Betty Pages, recounting tales of Page’s life and adventures during the camera club days. Two biopics, Nico B’s Bettie Page: Dark Angel (featuring fetish model Paige Richards as Page) and Mary Harron’s The Notorious Bettie Page (with Gretchen Mol as the eponymous lead) were also bathed in wistful nostalgia, presenting Page as a risqué heroine in an age of uptight repression.

But Page was also revived and innovatively reconceived by a host of artists and comic-book writers. During the early 1980s, for example, talented illustrator Dave Stevens used Page as the basis for a leading character in his comic series, The Rocketeer, while the 1990s saw Dark Horse Comics release a comic-book series based on Page’s fictional adventures and Eros Comics followed suit with a number of tongue-in-cheek Bettie Page titles. And Page has also been the inspiration for many of artist Olivia De Berardinis’s critically acclaimed erotic paintings. Page, moreover, has been a powerful influence in the world of fashion and subcultural style, with many female rockabillies, punks and goths dying their hair and cutting it into ‘bangs’ to emulate the striking Bettie Page ‘look’.

A postmodern theorist such as Fredric Jameson might see the recycling of Bettie Page’s image in a condescending light, viewing the Page revival as part of a more general cultural malaise. In the late twentieth century, Jameson argues, original cultural production gave way to a new world of pastiche, a world where cultural innovation was no longer possible and people had ‘nowhere to turn but to the past’31 and a retreat into the ‘complacent play of historical allusion’.32

But John Storey has taken issue with Jameson’s postmodern pessimism. For Storey, Jameson’s account fails to grasp the new meanings actively generated through processes of cultural recycling. Rather than being a random, and uniquely ‘postmodern’, cannibalisation of the past, Storey suggests, the plundering of historical style is part of a tradition of appropriation, bricolage and intertextuality that has always characterised popular culture.33 Moreover, Storey argues, contemporary expressions of retro-styling and historical allusion – of which the Bettie Page revival is indicative – do not represent a depthless ‘imitation of dead styles’,34 but are practices of active cultural enterprise in which cultural symbols from the past are commandeered and mobilised in meaningful ways in the lived cultures of the present. From this perspective, then, the cult revival of Bettie Page can be seen as an active appropriation and reanimation of a cultural icon whose complex, pluralistic performances of 1950s femininity offer enticing opportunities for parodying and destabilising dominant gender archetypes.