In 1982, a television news crew from the Midwest arrived in Los Angeles to document the making of a pornographic film. The adult videotape market was just beginning to surge, inspiring these savvy TV journalists to take a behind-the-scenes look at a typical porn production. The news crew’s presence on the set only added to a general atmosphere of controlled chaos: the entire film had to be shot over eleven days in a small studio in the heart of downtown LA; electricity was being illegally patched-in to power the equipment; and extras were recruited from a nearby blood bank and methadone clinic. After three days on the set, the news crew went home, titillated and satisfied that they had gotten their story. It was not however, exactly the story they thought they were getting. Though they were unaware of it at the time, they were not so much witnessing the making of a typical porno as the making of a cult film. While featuring hard-core sex, the film that they saw being made departed from many of the conventions of adult films, and would find its greatest success not in porn theatres, but on the midnight movie circuit. That film was director Stephen Sayadian’s second adult feature, Café Flesh.

The works of Stephen Sayadian (aka ‘Rinse Dream’) stand out as some of the most interesting and complicated in the adult genre. Sayadian made Night Dreams (1981) and Café Flesh (1982) in collaboration with writer Jerry Stahl and cinematographer Frank Delia, and both films are notable for their novel approaches to sound and performance, as well as their complicated relationship with the audience. In reviews of Sayadian’s films, one often finds phrases such as ‘the thinking-person’s porn film’, suggesting their uncertain relationship to the porn genre.1 Indeed, both films feature idiosyncratic stylistic choices that were intended by the filmmakers to confound the generic expectations of the porn audience. Sayadian’s distinctive soundscapes complicate the meaning of onscreen hard-core action, and demonstrate the importance of sound in the cinematic depiction of sexual fantasy. Performance is one of Sayadian’s central themes, and his films feature styles of acting that are typically associated with the avant-garde. Paradoxically, provocative stylistic techniques such as these provided their own powerful eroticism, and helped the films to flourish in contexts of reception outside of porn. The style of Night Dreams and Café Flesh is best understood when placed in dialogue with a historical account of the production and reception of these films. Sayadian’s career provides a lens onto a pivotal time in the history of the porn industry, and can allow us to explore connections between porn and other forms of cultural production, such as the magazine industry of the 1970s, cultures of avant-garde and midnight movies in the 1980s, and the rise of the home video market.

FROM HUSTLER TO HOLLYWOOD

Before turning to Sayadian’s film work in the 1980s, it will be useful to begin by considering his earlier career in the magazine industry. Indeed, the team that produced Night Dreams and Café Flesh – Sayadian, Stahl and Delia – met in the mid-1970s while working at Larry Flynt’s Hustler magazine. Sayadian had come to the magazine as a satirist, having previously submitted work to Mad Magazine, Marvel Comics and National Lampoon in the early 1970s. In the fall of 1976, Sayadian – then twenty years old – took his portfolio to Larry Flynt in Columbus, Ohio, who hired him on the spot as Hustler’s creative director in charge of humour and advertising. This position entailed making the advertisements for Flynt’s novelty sex products: “There were no advertisers,’ Sayadian recalls, ‘we made our own advertising.’ In fact, Sayadian asserts that Flynt made more money from sex products than from sales of the magazine.2

Flynt and Sayadian’s goal was to make the advertising share ‘the same sensibility as the rest of the magazine’, to imbue every aspect of Hustler with their nervy sense of satire so that, as Sayadian says, ‘when you looked at the advertising, you wouldn’t know if it was a parody or if it was real.’3 Consider Sayadian’s contributions to the January 1977 issue of Hustler (vol. 3, no. 7). This is, in fact, Sayadian’s debut, and the editors welcome him to the team in the front-matter of the issue: ‘Steve is now a member of Hustler’s advertising staff, where he can apply his distaste for ridiculous sales pitches to ensure honesty and a clever approach to our ads.’ One such ad, entitled ‘Love Doll’, features a bizarre photo of a cartoonish prison inmate chomping on a cigar. His cell is a minimalist blank set, with bars that represent a window, a toilet, and a few photos suggesting a wall. He cradles in his arms an inflatable doll – in actuality a living nude model – who it appears he has just removed from the box. ‘Leisure Time’s inflatable Love Dolls have countless uses’, the ad copy asserts, ‘traveling companion, gag gift, conversation piece, bunk mate…’ The description of the ‘Susie’ doll is as follows: ‘No moving parts, but a certain quiet charm. Easy to beat at poker. Washable.’

Ads such as this feature a visual style and twisted sense of humour that make them blend in with ad parodies found in the same issue. In a feature called ‘Hustler Takes a Look at Madison Avenue’, Sayadian presents a gory send-up of Playboy’s famous ad campaign. Above the caption ‘What Sort of Man Reads Slayboy?’ we see a gruesome photo of a dapper man in smoking jacket and pipe, surrounded by the bodies of three Playboy bunnies he has apparently killed. A similarly gory parody of a Curtail chainsaw ad depicts Sayadian himself, reclining in an elegant white suit, chainsaw in hand, surrounded by bloody severed limbs. The themes of violence and dismemberment continue in the ‘STUDential Life’ ad parody, wherein a woman, seated at an elegant dinner table, smiles while preparing to slice into the large severed penis on her plate.

Though certainly crass, Sayadian’s work at Hustler has a media-savvy, confrontational edge that makes it similar to the aesthetics both of Mad Magazine and National Lampoon. Such ad parodies were a central part of Hustler’s style, and subsequent issues would take aim at the cigarette industry as well as the Rev. Jerry Falwell in the famous 1983 Campari ad campaign parody, ‘Jerry Falwell Talks About His First Time’. It is not surprising then, that Michael O’Donaghue – influential writer for the National Lampoon and Saturday Night Live – wrote the Hustler staff a fan letter, declaring it to be his favourite magazine.4 Nor is it surprising that Laura Kipnis would observe that Hustler was like a ‘Mad magazine cartoon come to life’.5 As we have seen, much of the credit for the development of that style goes to Sayadian, as well as a larger creative team at Hustler that included photographer Delia and writer Stahl.

When Sayadian’s approach to satire was combined with hard-core sexual images, the result was a presentation of the body that was at once erotic, dark, playful and anxious. This is certainly not the upscale, air-brushed fantasy of Hugh Hefner’s Playboy. Consider that in the issue of Hustler described above, one cannot only see pornographic images of naked women and men, but also gory ad parodies with severed penises, and a graphic feature on war atrocities entitled “The Real Obscenity: War.’ Indeed, Hustler succeeded in part because its vulgarity and political edge appealed to the same college audience that was consuming the twisted satire of National Lampoon. While it would be ridiculous to assert that the magazine’s notoriously explicit nude photos played only a small role in its success, Sayadian and Stahl’s twisted black humour were nevertheless important factors in the magazine’s style and can help to contextualise both Flynt’s magazine and their subsequent film work.

Regardless of the source of its appeal, it is undeniable that Flynt’s magazine experienced phenomenal growth in the late 1970s. Sayadian recalls that, when he came to Columbus, the magazine was selling about 200,000 a month, but within a year and a half that figure was three million, and it was only ‘a handful’ of people doing it.6 In the wake of such growth, Flynt moved his corporate headquarters from Columbus to Los Angeles: ‘We went from this funky building [in Columbus] to the top floors at Century City. I mean the growth was ridiculous.’7 Flynt and company had plans to expand into other media, specifically film. ‘We had such plans,’ Sayadian remembers, ‘we were going to start our own film company. We were going to make horror films, off-beat films.’8 All these plans had to be put on hold, however, when Flynt was shot in Lawrenceville, Georgia on 6 March 1978. While Flynt began his long, painful recovery, he lost control of much of his media empire, including the film company.

Stahl, Sayadian and Delia had moved to LA with Hustler, where the latter two men opened an art design studio. They continued to work on a contract basis with Hustler, but also began making posters and one-sheets for Hollywood films such as The Fog (John Carpenter, 1980), Dressed to Kill (Brian De Palma, 1980) and Escape From New York (John Carpenter, 1981). Their studio was located in the Cherokee Building in downtown LA, which also provided practice space for local punk rock bands such as the Germs and Wall of Voodoo, and office space for Brendan Mullen, the owner of LA’s premier punk rock club, The Masque. This overlap with the LA punk scene was to have an influence on Sayadian’s subsequent film work: ‘there was a sub-genre of punk which sort of crossed into the movies I was making, and that had more to do with geography than anything else.’9

This geographical influence on Sayadian’s work suggests a connection to what Joan Hawkins describes as a ‘late twentieth-century avant-garde’ that emerged in the 1980s when artists and filmmakers began moving downtown – to the East Village in Manhattan, the warehouse district in Chicago, and the South Market area (SOMA) in San Francisco.10 These depressed areas had yet to be gentrified and contained cheap studio space for artists, filmmakers and musicians. Hawkins argues that diverse downtown artists and filmmakers such as David Lynch, Nick Zedd, Richard Kern, Larry Fessenden, Todd Haynes, Kathy Acker and Tom Palazzolo were united by a ‘common urban lifestyle’ and ‘roots in the punk underground’ as well as ‘a shared commitment to formal and narrative experimentation, a view of the human body as a site of social and political struggle, an interest in radical identity politics and a mistrust of institutionalized mechanisms of wealth and power’.11 Importantly, many of these downtown filmmakers borrowed heavily from ‘low’ cultural forms such as ‘erotic thrillers, horror, sci-fi and porn’.12 The films made by Sayadian, Stahl and Delia in the early 1980s fit the general outlines of the downtown avant-garde. However, where many downtown filmmakers were incorporating aspects of pornography into avant-garde film, Sayadian made the opposite move, bringing techniques associated with art films to his first adult feature: Night Dreams.

NIGHT DREAMS

The opening credits of Night Dreams list Stahl as writer, Delia as director and Sayadian as producer. Stahl and Sayadian wrote the script together, and Sayadian oversaw the shooting: ‘Jerry was never on the sets. We worked really well together because I was sort of in charge with the visuals and he was in charge with the dialogue.’13 I say that Sayadian, Stahl and Delia are credited in the film, but in fact, the names that appear are aliases. Delia became F. X. Pope, Stahl became Herbert W. Day (the name of a high school principal he wanted to saddle with the title of pornographer), and Sayadian became Rinse Dream: ‘Jerry started calling me that, and then everybody followed.’14 These aliases were used in part to avoid the LA Vice Squad.

At the time, working in porn required the acceptance of a certain level of risk, though it also meant the possibility of financial backing. Night Dreams was made for a budget of $65,000, supplied by what Sayadian calls ‘traditional porno people’, though the final film itself was anything but traditional. In fact, Sayadian stated that ‘it took a lot of charm and boyish enthusiasm’ to convince his financial backers not to break his arms: ‘but they liked me, and that goes a long way’.15 Indeed, neither Night Dreams nor Café Flesh were successful on the porn exhibition circuit. Yet it was the very stylistic techniques that prevented these films from working in porn theatres that allowed them to succeed in other reception contexts. Thus, in order to understand the cultural life of Sayadian’s films, we will need to consider the idiosyncratic ways in which sound, performance and narrative function within them.

The narrative of Night Dreams is structured around sessions in a surreal sex therapy clinic. The first image we see is an extreme close-up of Mrs. Van Houton (Dorothy Le May), kneeling in a stark white clinical observation room, electrodes connected to her forehead. She looks directly at the camera and says, ‘I know you’re watching me. I feel your eyes like fingers touching me in certain places.’ The camera cuts to a shot of a male and female doctor (Andy Nichols and Jennifer West) observing Mrs. Van Houton on the other side of one-way glass. For the rest of the film Mrs. Van Houton delivers direct-address stream-of-consciousness monologues to the camera that segue into stylised sex sequences while, on the other side of the glass, the exasperated doctors try to make sense of her behaviour. This structure distances the sex scenes from the film’s larger narrative, creating a certain ambiguity as to whether the fantasies are those of Mrs. Van Houton or the doctors.

The role of the therapists in Night Dreams differs from male sexologists in adult films such as Deep Throat (Gerard Damiano, 1972) and The Opening of Misty Beethoven (Radley Metzger, 1975). For Linda Williams, such figures occupied the position once held in literary pornography by the libertine, whose ‘scientific knowledge of the pleasure of sexuality’ leads to the variety of sexual numbers.16 In Night Dreams we find a different dynamic: the sexual numbers are presented as arising from the fantasies of the female client, not the male sexologist. In fact, not only is the male doctor subordinate to the female doctor (‘don’t forget who’s assisting who’, she tells him at one point), but neither of the therapists are found to be in control of the situation. That is, the film ends with a surprise role reversal: the doctors are revealed to be the clients/patients when Mrs. Van Houton emerges from the observation room and asks, ‘Will I see you next week?’ In robotic unison, the two doctors turn to each other and reply, ‘Do we have a choice?’

Thus the use of the therapy motif in Night Dreams does not work so much to anchor the sex to a male authority figure, but instead to motivate the film’s surrealist stylistic excess. Stahl wrote in an email interview that ‘therapy is the perfect way into the surreal. Not to mention that its inherent power structure invites sexual parallels.’17 Indeed, the film is peppered with moments of flat-out, avant-garde weirdness similar in tone to David Lynch’s Eraserhead (1976). In one scene, Mrs. Van Houton pulls a fetus from a man’s trousers, in another she relaxes and shares a cigarette in what seems like post-coital bliss with a large fish. Set designs are minimalist and stylised, at times resembling the Hustler advertisements described above.

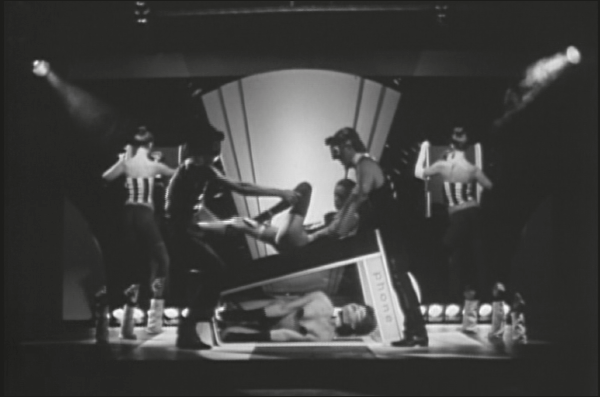

FIGURE 2.1 ‘Avant-garde weirdness’ as sexual thrill in Night Dreams

While the narrative and imagery set Night Dreams apart from most adult films, we should also note how Sayadian’s film sounds. For one thing, Night Dreams features the use of recorded music to make critical and satiric comments on the accompanying images: in one sequence, Mrs. Van Houton performs oral sex on an African American man wearing a cardboard Cream of Wheat box – literally the corporate trademark come to life – as the soundtrack plays the Ink Spots’ light jazz version of ‘Old Man River’; later Sayadian make ironic use of Eric Satie’s ‘Trois Gymnopedies’ and we hear a recording of Johnny Cash’s ‘Ring of Fire’ as performed by Cherokee Building denizens Wall of Voodoo. Sayadian stated that simply hearing ‘a cutting edge band’ like Wall of Voodoo on an adult soundtrack at this time was ‘unique’. In fact, one of the most distinctive aspects of Night Dreams is the use of sound.18

SOUNDSCAPES OF DESIRE

The generic conventions of the porn soundtrack call for what Rich Cante and Angelo Restivo call porno-performativity: post-synced moans and asides that function to authenticate the pleasure of the (typically female) performers.19 Such vocalisations are often accompanied by slick, trance-inducing dance music (disco, funk, or more recently techno) played by anonymous session musicians. That kind of clichéd porn music is completely absent from Night Dreams, and while the film does contain porno-perfomativity, it is overshadowed by stunning musique concrete-style multitrack soundscapes. In order to get a sense of how these soundscapes function in the film, it will be necessary to consider them in relation to theoretical writings on film sound, pornography and sexual fantasy.

Returning to the opening moments of the film, we hear the sounds of amplified heartbeats and breathing over a black screen, and then cut to the close-up of Mrs. Van Houton in an observation room. After the initial dialogue, fast cuts of the oversized faces of dolls mark a transition to a fantasy sequence that takes place in a dimly-lit children’s playroom where a huge jack in the box pops open to reveal a sinister-looking clown, his penis exposed through his garish costume. As Mrs. Van Houton and the clown engage in oral sex, we hear loops of high-pitched laughter, a distant rhythmic chanting, and sounds that resemble the squeaking of plastic toys. The distant laughter and chanting in this scene contrast with the ‘too close’ quality of over-dubbed porno-performativity. Linda Williams describes how post-sync ‘sounds of pleasure’ have a certain clarity that makes them seem to come from very close up. Not only does this lend a certain ambiguity as to the performer’s position in space (a sense of ‘spacelessness’), but porno-performativity also provides an index of intimacy.20 The loops of laughter and distant chanting in the scene described above frame the onscreen sexual action in a different kind of space.

In fact, there is an intimate relationship between sound and space, which might be encapsulated in the term ‘sonotope’, which designates the sonic representation of a particular space.21 Sound always contains messages about the space through which it has passed. Consider for example, a sound that is ‘wet’ with reverberation. That ‘wetness’ is actually a perceptual image of the source of the sound combined with the influence of the large reverberant space through which the sound has travelled. Sonotopes can shape how we understand the performances given within them and the images that accompany them. Sonotope can be a useful concept for considering the genre of film pornography when one considers arguments that sexual fantasy is best understood not as a linear narrative with a fixed subject position, but as a certain setting, atmosphere or ambiance capable of sustaining a set of interconnected relationships and points of view.22 If fantasy is best understood as the setting of a scene, and sound is uniquely able to convey the experience of space, then sound design emerges as a central aspect of the representation of sexual fantasy in adult film. Sound is a powerful – perhaps the most powerful – index of setting, and the choice of sonotope employed in a particular scene will profoundly shape the subsequent experience of fantasy.

Because of its novel approaches to sound design in a hard-core context, Night Dreams provides a rich text for the consideration of what might be called erotic sonotopes. I have already mentioned how the over-dubbed moans of porno-performativity suggest a certain sound-space: the closeness of intimacy. Sayadian’s use of sound in the sex scenes described above frames the on-screen sex as occurring within a larger space, at the margins of some other off-screen activity. That is, the distant laughter, chanting and murmured speech, frame the sex as somewhat obscure or secret, thus subtly heightening its erotic affect. We might identify another sonotope in a sequence in which Mrs. Van Houton masturbates in front of a bathroom mirror before being attacked by a masked stranger who has been watching her from an open door. The soundtrack during this scene features a dripping faucet saturated with reverb, as well as atonal electronic music in the style of Morten Subotnick’s 1967 composition, ‘Silver Apples of the Moon’. The reverberant dripping faucet places the listener within a wide, open space with hard surfaces: not so much a bathroom as a concrete parking garage or empty industrial warehouse. A similar kind of space is suggested in a later sequence in Night Dreams, when Mrs. Van Houton finds herself in ‘hell’, involved in a ménage a trois with a devil prone to bizarre non-sequiturs and one of his female slaves. The soundtrack features blistering sheets of white noise as well as loops of clanging industrial machinery and the distant cries of the damned.

The ‘industrial’ sonotope heard here is indicative of a setting quite prevalent in film pornography. Perhaps part of its appeal is the way in which it suggests an exhibitionistic fantasy of sex in open, public spaces. But such a frame for sexual imagery also establishes a contrast in terms of texture: the cold, hard industrial spaces suggested by the soundtrack clash with the soft, warm wetness of sexual intimacy, thus creating an arresting dissonance. What becomes clear is that Sayadian’s use of pre-recorded music, tape loops and sonic collages creates a range of evocative sonotopes that in turn frame the film’s hard-core sequences with a distinctive emotional tone. In the end, Sayadian’s approach to sound has less to do with the conventions of porn than it does with the soundtracks of ‘downtown’ filmmakers such as David Lynch. Hawkins points out that the work of avant-garde downtown artists frequently attempted to ‘directly challenge the viewer.’23 The desire to challenge both generic conventions and the expectations of the porn audience were key factors in the next film made by the Sayadian, Stahl, Delia partnership: Café Flesh.

FIGURE 2.2 Sadism and sonotope: aural and visual landscapes in Night Dreams

FIGURE 2.3 Complicating carnality: the self-reflexive thrills of Café Flesh

CAFÉ FLESH

This time, Sayadian’s budget was $100,000, all of which came in bags of change since its financial backers were in the coin-operated peep show business. As noted above, the film was shot in eleven days in Sayadian’s studio on one of the busiest street corners in Hollywood, the crew in constant fear of being busted by the Vice Squad while bumping elbows with a leering network news crew. At one point, Sayadian’s landlord demanded to know why there were so many people – including half-clad women – on the premises. Sayadian recalls telling him that he was ‘doing rehearsals without the skates for the Ice Capades. He bought that’.24

If Night Dreams was a generic hybrid of porn and downtown art film, Café Flesh combined the adult genre with both the movie musical and post-apocalyptic science fiction. Stahl wrote that their goal was ‘to perpetrate a World War III musical. We had in mind a kind of high-rad Cabaret in which trendy mutants and atomic mobsters held sway over survivors bombed beyond all normal pleasures. Lots of people made movies about the end of the world, but how many showed what the night life would be like?’25 The plot hinged on the idea that after a nuclear apocalypse 99 per cent of the survivors would be ‘D.O.A. between the legs’:

These were the Sex Negatives. Unable to relieve their lust – they got nauseated when they tried – the Negs nevertheless craved the sight of others who could still pull off the act. These others, the functioning one per cent, were called Sex Positives. By rigidly enforced edict, Pozzies were required to perform for Neggies. And the ‘in’ spot where all the lame and denatured went to slaver? Café Flesh, post-nuke Copacabana.26

The presentation of a world in which sex is cast in terms of paranoia, anxiety and mysterious dysfunction has often been seen as a prescient parable for the dawning AIDS era – in fact, the disease was first named in 1982, the year of the film’s release. ‘When we did Café Flesh, the whole thing with the positives and negatives’, Sayadian stated, ‘that was six months before AIDS, and everyone has always seen the parallel.’27

The plot of Café Flesh – like Night Dreams – separates narrative and sexual numbers quite starkly. Again, this allows for stylistic excess: where therapy allowed avant-garde imagery in Night Dreams, a Busby Berkeley-style floorshow is an excuse for surreal costumes and sets in Café Flesh. The separation of narrative and number also has implications for the film’s relationship with the audience. Joan Hawkins notes that Café Flesh is ‘a self-reflexive porn film, one that is not at all easy about the circumstances (mandated spectacularized sex) of its own production’.28 Indeed, as with Night Dreams, the viewer is forced to identify in an uncomfortable and unflattering way with an onscreen surrogate audience: in this case, the impotent Sex Negatives.

FIGURE 2.4 Pornoscapes and the postmodern musical number: modes of performativity in Café Flesh

FIGURE 2.5 Tears from the ‘chronically passive audience’: erotic viewing as trauma in Café Flesh

Consider the opening titles of the film: ‘After the nuclear kiss, the Positives remain to love, to perform … And the others, well, we Negatives can only watch … can only come … to … CAFÉ FLESH.’ From the beginning of the film the audience is explicitly placed in the position of the dysfunctional Negatives. Further, throughout the film, shots of sex are intercut with images of the gawking audience, presented in a grotesque style akin to the photographs of Diane Arbus. In one particularly startling juxtaposition, an on-stage money shot is immediately followed by the image of a male audience member with a tear rolling down his face. In this jarring moment we move from the ‘pornotopia’ of the money shot to the depiction of both the audience in the film and by extension ourselves as pathetic, chronically-passive observers. We might observe that while the film separates narrative and number – a kind of porn narrative that Linda Williams argues tends to be ‘particularly regressive and misogynist’ – it still contains a self-reflexive genre critique on the level of narrative and style.29

It should be noted that the sex number that inspired the audience member’s tear was anything but typical porno fare. While on the soundtrack we hear loops of industrial machinery, behind the stage at Café Flesh we see an impressionistic backdrop of oil rigs. Meanwhile, a naked secretary blankly pokes at a typewriter while another woman in lingerie reclines on an office desk. A man wearing a suit and enormous pencil mask emerges, stiffly dancing to music on the soundtrack. The pencil-man proceeds to engage in fairly robotic sex with the woman on the desk, while the secretary repeatedly addresses the camera, intoning, ‘Do you want me to type a memo?’

FIGURE 2.6 A hard(core) day at the office: cliché as erotic distanciation in Café Flesh

MAGNITUDES OF PORNO PERFORMANCE

Thus far I have been focusing on the use of sound in Sayadian’s films. But the secretary’s performance in the sex scene described above is illustrative of Sayadian’s equally distinctive approach to acting. In fact, Sayadian stated that the decision to shoot Café Flesh was largely based on questions of acting. That is, the plot allowed him to work with better actors than were typically found in the adult industry: ‘I was trying to say, “How can I make a porno film where I can use some decent Off-Broadway-style actors that don’t have to have sex, and yet I need sex. How can I do that?” And I said, “Well, if I did a club, where they watch people have sex, then I don’t need everybody to have sex.”’30 Similarly, Stahl wrote that the ‘best part’ of the plot was that most of the ‘Chucks and Suzies’ who had to ‘lock femurs onscreen never had to utter a word – a definite plus.’ As he continued, ‘Your solid porno pro, as gifted as he may be at expressive rooting, generally lacks dramatic verve when it comes to mouthing dialogue. But the way Café Flesh was remolded, just about all the snappy patter could be handled by “real” actors (out-of-work Strasberg grads and sitcom hopefuls). And the sex, pesky business, ended up in a series of choreographed side shows – stagy diversions, I like to think, in the gala tradition of the June Taylor dance segments on the old Jackie Gleason Show.’31 The separation of club performers and audience, of Positives and Negatives, thus allowed for a division of labour in terms of acting. Some of the ‘sitcom hopefuls’ who appeared in the film but didn’t have sex were Paul McGibboney (Nick, the romantic lead), Andy Nichols (the male doctor from Night Dreams, here the emcee of Café Flesh, Max Melodramatic), and even an uncredited cameo by comedian Richard Belzer as a loud-mouthed patron.

If the narrative allowed for more professional acting performances from some of the cast, the actors who did ‘lock femurs onscreen’ were given unusual direction from Sayadian:

Most of the people that make their living having sex, it was true back then and I’m sure its true now, they enjoy it. That’s why they’re in the business. Every time they began to enjoy the lovemaking and the sex during the filming I would call cut. I would say, ‘You look like you’re enjoying it, I want you to think of the worst memory of your life while you’re doing this. I want it very unpleasant. Not that you’re being raped, that’s not the point. But I want it to be as mundane as if you were a clerk typing or filing, I want you to approach it like that.’32

In addition to making the audience aware of itself as passive, even dysfunctional voyeurs, the film therefore also calls attention to the perfunctory, and (most damning of all), routine quality of the performance of sex in film pornography. Typically, porn performers utilise techniques designed to ostentatiously externalise feelings of sexual pleasure. In Café Flesh however, sex performers wear the blank expression of the avant-garde. More specifically, these performances resemble those made by what James Naremore refers to as the ‘antirealistic Brechtian player’, who is ‘concerned less with emotional truth than with critical awareness; instead of expressing an essential self, she or he examines the relation between roles on the stage and roles in society, deliberately calling attention to the artificiality of performance, foregrounding the staginess of spectacle, and addressing the audience in didactic fashion’.33

I have already noted the use of direct address in Night Dreams. This technique is also found in Café Flesh, particularly when Max the emcee speaks directly to the camera as he addresses the audience at Café Flesh. Sayadian also tends to have characters chant lines of dialogue in unison, preventing the audience from losing itself in the world of the story. In a hard-core context, such Brechtian techniques can serve to further objectify the performer as a sexual object, what Naremore calls ‘pure biological performance’.34 That is, antirealist techniques allow the audience to see through the role being played by the actor, allowing the performer to be perceived in social terms or as pure bodily presence. But in Sayadian’s films, this performance style also works to short-circuit the belief that the performance of intimate sexual acts somehow reveals a privileged or essential expression of the actors’ selves. By foregoing attempts to naturalise the sex, the audience is encouraged to see it as spectacle, one that is just as much a constructed performance as the delivery of ostentatiously scripted lines.

FIGURE 2.7 Masking the self: concealment as porno performativity in Café Flesh

Given this foregrounding of performance, it is interesting to note how frequently masks appear as a motif in Sayadian’s films: the jack in the box and the male attacker in the ‘Dressed to Kill’ sequence in Night Dreams; anonymous figures in white masks and a milkman who wears a rat mask in Café Flesh. Masks of course, are a ‘classic prop in pornographic representation’ because they allow the wearer an anonymity and resulting sense of sexual license, but as theorists such as Mikhail Bakhtin have argued, the mask is also a powerful emblem of metamorphosis, as well as the performative nature and fluidity of the self.35 The presence of all these masks is one more indication of how Sayadian’s films thematise performance, rejecting a presentation of sex as a utopian route to the self.

MIDNIGHT DREAMS

Such a depiction of sex was bound to frustrate much of the porn audience – which in fact, was one of the goals of the filmmakers. Jerry Stahl wrote in an email interview that ‘we wanted [the audience] to be repelled – it’s not like we wanted to be making porn.’36 In another interview, Stahl stated that they had intentionally ‘stuck in the most objectionable, repulsive kind of sex we could imagine. Really cold and chilly and weird.’37 However, as the avant-garde use of sound in Night Dreams had paradoxically made the film even more erotically potent, the style of Café Flesh led not only to the film’s failure on the traditional porn theatre circuit, but also to its remarkable second act as a midnight movie cult film. Sayadian explains that when Café Flesh was released in adult film houses, ‘it did nothing’: ‘It played at a couple of porn theatres. There was literally a riot in one theatre, people demanding their money back.’38 The film was pulled out of distribution, and sold to another company where it sat on the shelf. According to Sayadian, a young marketing executive at that company came across the print, and decided to re-release it not as a porno, but as a cult film. To this end, the film was shown at the NuArt theatre in LA: the home for midnight movie classics including John Waters’ Pink Flamingos (1972), The Rocky Horror Picture Show (Jim Sharman, 1975) and Eraserhead. The NuArt put up money for an ad campaign, and on its first night the film broke the house record. Café Flesh proceeded to break the house record for six consecutive weeks, and played there for over a year.39 From this beginning at the NuArt, word of mouth about the film began to spread. Soon Sayadian was fielding calls from college campuses and art theatres, and booking the film in both the US and Europe.

J. Hoberman and Jonathan Rosenbaum have written that successful midnight movies tended to offer relevant social metaphors that usually had to do both with transgressing taboos and ‘articulating a potent, new fantasy’. The Rocky Horror Picture Show, in their view, became a midnight blockbuster in part because it recapitulated 1960s sexual politics while also creating ‘a kind of adolescent initiation’.40 What relevant social metaphor did Café Flesh offer the midnight audience?

The first thing to point out is that Sayadian’s films, with their stylised sets and performances, and bizarre, kitschy humour, certainly had camp appeal. In fact, Sayadian has noted that based on his interaction with fans, a large proportion of his audience were gay men.41 In fact, while they do not depict any gay male sex scenes, the clearest ‘social metaphor’ that Café Flesh offers has to do with sexual politics in the wake of AIDS. But also consider that Café Flesh’s success at the NuArt, and later on the cult circuit was due in part to the film’s resonance with punk subculture. The extras who played the Negatives watching sex acts at Café Flesh were taken, according to Sayadian, ‘right from the blood bank and the methadone clinic’, and tended to be part of the LA punk scene.42 As a result, Sayadian states that screenings of the film became a popular punk hang out. In Stahl’s words, the film’s ‘synthesis of punk fashion and 1950s dialogue’ gave it a particular appeal to ‘youthful art victims’: ‘In Los Angeles, at least, part of what fueled its 18-month run was that half the town’s underground avant actually appeared in the movie. This bestowed on us a built-in cachet among local Nuevo-ettes, a breed of heavily mascaraed existential gals who smoked Gitanes and kept tattered copies of Naked Lunch in the glove compartments of their Karmann-Ghias.’43

Sayadian’s film is thus ‘post-apocalyptic’ on two levels – in the literal sense of being set after a nuclear holocaust, but following Jonathan Rosenbaum, it is also post-apocalyptic in the sense that Eraserhead is: ‘if we take the “apocalypse” to be the dissolution of the counterculture’.44 Sayadian’s stylistic choices regarding performance – in large part pragmatic responses to the logistical imperatives of porn production – ended up shaping an aesthetic that ran parallel to a punk subculture that took an unsentimental, jaded view of sex, and rejected the 1960s countercultural assertion of the liberating potential of free love. Café Flesh offers a metaphoric depiction of changing sexual mores in the Reagan era, when AIDS, punk and a conservative cultural backlash would drive a stake through the heart of the free love ideal of the counterculture.

Indeed, the film’s blasé presentation of hard-core sex stands as a fitting reflection of the porn industry in the early 1980s. Driven from mainstream theatres, porn was nevertheless rapidly becoming a ubiquitous commodity on videotape. Café Flesh’s crossover success from porn to midnight movie came at a time when both were feeling the effects of the emerging home VCR market. Home video was an important factor in the demise of the midnight movie circuit, another being the Reagan administration’s encouragement of entertainment industry monopolies, which subsequently forced small exhibitors out of business.45 Meanwhile, the market for porn was opening up to a wider couples audience watching on home VCRs, who were perhaps more interested in the kind of overt stylisation found in Night Dreams and Café Flesh. In trying to account for his film’s surprising success, Sayadian stated that Café Flesh ‘allowed people that normally didn’t want to watch porno because it was so bad cinematically, to say, “I can watch this one because it’s kinda got a hip sensibility.” So that while you’re watching, you don’t have to feel self-conscious that I’m watching some really bad smut. I’m watching something kind of interesting. And lo and behold, it’s a bit of a turn on.’46

Sayadian’s films have a complex relationship to the adult genre – the men who made them had mixed feelings about working in porn, helping to fuel a desire to play with its conventions and to challenge its audience. The paradox is that, in pushing those boundaries, these films have become seminal and much-imitated texts in the adult industry. This is not surprising, considering that Sayadian’s provocative use of sound and performance in the service of hardcore erotica stand as some of the most original and evocative explorations of the spaces of sexual fantasy. But the cultural life of these films demonstrates that the genre of film pornography cannot be seen in isolation. That is, Sayadian’s work is best understood as a complex intertextual hybrid that overlaps with cultures of magazine satire, subcultures of popular music, avant-garde film and adult film, and midnight movies. As such, these films illustrate the need to consider film pornography in connection with adjacent media forms, and to avoid sweeping generalisations about porn production.

Author’s note

I would like to thank Stephen Sayadian and Randi Fiat for being so generous with their time. Also thanks to Jerry Stahl and Frank Delia for taking time to answer my questions; to Brad Stevens for helping me track people down; and to Glenn Gass for help with obtaining images. Finally, many thanks to Prof. Joan Hawkins for reading an early draft and offering suggestions, encouragement and inspiration.