The backlash against disco music occurred in July 1979 when a Chicago baseball park was witness to an anti-disco riot fuelled by the blowing-up of a pile of twelve-inch disco singles. This event was billed as Disco Demolition Night and was the culmination of a phobia hystericised by the slogan ‘Disco Sucks!’. The anti-disco sentiments of ‘Disco Sucks’ has two meanings here; on the one hand the music sucks because it’s considered rubbish and on the other hand disco fans suck, as in they suck cock. In other words, ‘Disco Sucks!’ is a rather thinly veiled homophobic and anti-women agenda.1

I want to open my chapter with this reminder because it suggests such strong links between music and sex, or rather disco and fellatio, consumption and cultural identity, and in the context of this volume the overlap between a music genre and the genre of pornography. Therefore, I will be exploring the different connections and mutually reflecting discourses relating disco and pornography during the 1970s, in terms of the general erotic underpinnings of disco music, how it sounds, the associated images, discotheque spaces, and the enmeshment of disco in gay culture and the sexual culture of the 1970s.

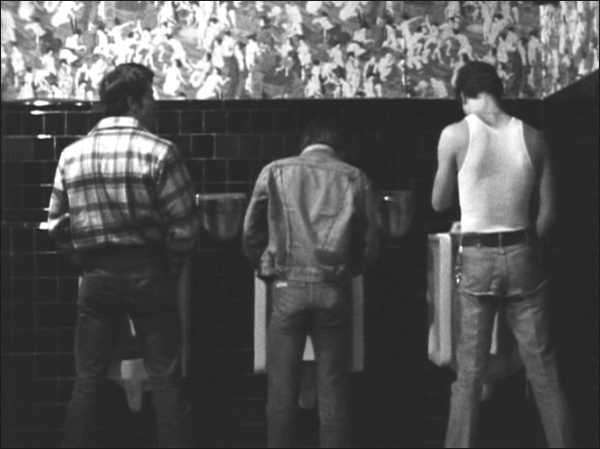

FIGURE 4.1 Sensual revolutions and the sexual backlash: music and marginal sexuality conflated

The everyday use of the word ‘disco’ today is a catch-all term for danceable music from the 1970s but rarely does contemporary usage reflect the complexity and historicity of disco, what it truly meant, what the experience was like, and how it sounded. Disco is certainly not associated with cultures of gay sex, pornography and female orgasms. This is because the de-historicisation and de-politicisation of the genre and culture, including its links to gay liberation and women’s liberation, has turned disco into merely the mainstream fodder of an inauthentic nostalgia for the 1970s. For those of us who do know and love real disco, and I mean here expert knowledge about disco music, history and culture, will bemoan the distortion of its legacy in which ABBA and The Village People rather than Suzi Lane, Theo Vaness and Taana Gardner take on the ambassadorial function. In the popular imagination disco mainly survives and is inculcated through songs that were big chart hits during the 1970s rather than the actual music that was heard as part of the disco experience. One only has to refer to deejay charts, sets and mixes from the period to see this major difference between what was experienced as disco and what now gets passed off as disco. This lack of continuity and authenticity is obvious in films like The Last Days of Disco (Whit Stillman, 1998) and 54 (Mark Christopher, 1998) in which every well-known chart-topping disco song can be heard during the disco scenes. The music in The Last Days of Disco is too wide-ranging with tracks spanning several years in a period constructed as the end of 1980; the music is chosen because it is well known rather than an authenticating reflection of a disco’s music policy in 1980. The logic here of course is to sell a soundtrack, thus historical accuracy has to be dispensed with but this also defines the general mainstreaming of disco post-1970s.

The effect of this posthumous re-organisation of the meaning of disco, the selective hearing process of cinema and the mainstream disco compilation of top-ten hits, are bound to a de-gaying and de-sexing of disco. Although the mainstreaming of disco is contemporaneously understood to be essentially a camp phenomenon, this version of camp has nothing to do with gay culture and more to do with a kitschy and trashy self-depreciating sense of the popular as solipsistic fun. Certainly, contemporaneously, disco has long been divorced from its relationship to cultural sexual experimentation and dissent, pornography, orgasms and gay abandon. Furthermore, disco always had a very different relationship to heterosexuality than it did to homosexuality; for example, disco’s queer relation never ended in 1980 with the same resonance of embarrassment that quickly ushered its straight fans into the disco closet.

Here I want to restore the relationship between disco and sexual culture, an epistemological mapping as it were, through the following salient features of interconnectedness between a music genre, cultural identity and a pornographic milieu. However, it should be noted, not all disco culture was related to sexuality and pornography; for example, the Sesame Street Fever (1978) album from the popular children’s television show, and one would be hard pushed to find anything erotic in relation to The Ethel Merman Disco Album (1979).

CRUISING THE BEATS: SPATIALISING DISCO AND PORNOGRAPHY

The origins of the disco scene begins in the late 1960s and early 1970s; the emergence of a dance music culture almost immediately following the Stonewall riot of July 1969 and the ushering in of gay liberation. These discos were private parties like The Loft and clubs like The Sanctuary, the latter described as ‘the cathedral of Sodom and Gomorrah’,2 spaces inhabited by a large gay clientele but also including those Americans marginalised and disenfranchised by race as well as sexuality. While the discotheque as a concept of leisure was in vogue throughout the 1960s as part of the ‘Swinging Sixties’ it quickly went into decline by the end of that decade. The decline of this earlier straight version of the discotheque was superseded by a different version of disco that privileged the role of the deejay in providing a danceable experience out of pre-recorded music, mixed and extended in near-seamless fashion without interruption, with the addition of drug-use and non-stop dancing, the experience was ecstatic and transcendental; when matched with gay liberation politics this was also tremendously affective. It was in these spaces of dancing with the music skilfully shaped by the deejay that the sound, the people and the venue merged into the concept of disco; the term comes to describe both the music and the space. Although the initial discos were about dancing, partying and meeting people they eventually, although not exclusively, transformed in to places that also accommodated sexual activity often sensationally described as such: ‘Put fifteen hundred gay boys in a private club, feed them every drug in the pharmacopoeia, turn up the music loud, and pour the drinks like soda pop – presto! You’ve got an orgy.’3 While the early discos were certainly not this way inclined, the notion of a public space for sex often informed the idea that the smaller gay dance clubs were also sex clubs, or at the very least had spaces that accommodated both sex and dancing, bodily activities not entirely unrelated.

Contemporary representations of the disco in film and retro fashion trends try their hardest to make disco appear erotically charged but ultimately fail to convey the complexity of its sexual dynamic. However, a number of articles from the period in The Village Voice,4 books like Albert Goldman’s Disco (1978) and Andrew Holleran’s gay literary classic The Dancer from the Dance (1978)5 appear during the latter part of the 1970s and through their immediacy offer a more attuned and nuanced description of the spaces, pleasures and identities of disco culture, offering a very different account from more recent popular conceptions. Goldman, the controversial music biographer and American Professor, wrote a widely-read book on disco, albeit from the point of view of his identity as a white heterosexual academic; the book tends to read like an anthropological discovery of a newly discovered tribe and treads a fine line between objectivity and sensation. What fascinates me about Goldman’s book, from which I have already quoted, is the lengthy passages given over to describing the spaces of the disco in sexual terms especially as he ventures into the darkest depths of the New York gay scene of the 1970s. Goldman’s narrative is akin to the structure of Dante’s Inferno; the author descends the circles of a disco hell looking on in a shocked awe, offering the reader licentious descriptions of sinners and sodomites. Take for example his description of the legendary disco Paradise Garage:

The Paradise Garage, the hottest gay disco, is an immense cast-concrete truck garage down on the docks (the gay’s happy hunting ground). As you climb its steeply angled ramp to the second floor, which is illuminated only by rows of sinister little red eyes, you feel like a character in a Kafka novel. From overhead comes the heavy pounding of the disco beat like a fearful migraine. When you reach the ‘bar’, a huge bare parking area, you are astonished to see immense pornographic murals of Greek and Trojan warriors locked in sado-masochistic combat running from floor to ceiling.6

As the book continues Goldman gets more feverish in this obsession with the gay sex unfolding in the discos that culminates in his description of the ‘discos with the orgy back rooms, where you stick your cock through a hole in the wall and hope for the best … where a hard-muscled hairy arm with a big fist plunges first into a can of Crisco and then so far up some guy’s asshole that his eyes bulge’.7 Goldman attempts to shock his reader with such descriptions of glory holes and fisting, and I admire his refusal to sanitise disco since his publication followed the commercial de-gaying and mainstream ascendancy of disco – those countless disco dancing instruction books that centralise complementary heterosexual pairings and of course the film Saturday Night Fever (1977). According to Goldman then, all manner of kinky practices unfold not just in the spaces of the disco but also because of disco.

The discos, along with the bathhouses, were important locations of gay sexual activity and socialisation in the 1970s, particularly in the way the spaces of the disco were organised to furnish areas for dancing and areas for sex although these were not mutually exclusive in terms of what happened and where. It’s important to stress that having sex and listening to disco could be simultaneous experiences. The discos described and documented no longer exist except in memory, the sexual escapades curtailed by the onset of AIDS in the early 1980s, the histories intertwined with personal recollection, most passionately written about in detail in disco pioneer Mel Cheren’s biography Keep on Dancin’ (2000)8 and in the documentary Gay Sex and the 1970s (Joseph Lovett, 2005). There is surviving footage of Paradise Garage, for example, in the house music documentary Maestro (Josell Ramos, 2003), and the continual over-exposure of Studio 54 on television and in pop culture, but there are so many spaces of disco life (nightclubs, bars, bathhouses, cinemas) once celebrated yet mostly undocumented, and certainly central to the formation of gay identity and sexual culture through the interlocking of sound and space as a collective experience. However, a number of these spaces of historical significance for disco dancing and music have found their preservation in the domain of gay adult cinema especially in those films which nominate the spaces for inclusion through a sort of ethnographic mapping and accompanying disco soundtrack. I am thinking here of Boys of Venice (William Higgins, 1978) which documents the East Coast gay disco and roller-skating scene in L.A., A Night at the Adonis (Jack Deveau, 1978) set in New York’s Adonis theatre, the soft-core comedy Saturday Night at the Baths (David Buckley, 1975) filmed in the Continental Baths, and Boots and Saddles (Francis Ellie, 1978) filmed in the once strictly-dress-code-policed ‘denim and plaid’ gay bar of the same name.9

The ethno-documentary impulse of gay pornography is also noted by Richard Cante and Angelo Restivo in their remarks that ‘feature length all-male filmic porn was deeply invested in narratologically and imagistically “gaying” such itineraries of everyday life’ of which I would suggest disco is one such location of meaning for a gay 1970s ontology.10

The mapping of gay life through film goes further back than this; the textual exchange between experimental film and documentary in films like Gay San Francisco (1965–70) forms a point of discussion in the underground cinema section of Richard Dyer’s Now You See It (1990).11 The commitment to filming on location in gay pornography, like in Boots and Saddles, is a testament to the way in which pornography is understood to be intrinsic to rather than separate from gay life during the 1970s. Films like Fire Island Fever (Jack Deveau, 1979) taught gay men how to cruise and pick-up, where they could hang out, and go on holiday to places like Fire Island. Bob Alvarez, the producer and editor of Hand in Hand’s A Night at the Adonis and Fire Island Fever has said ‘we tried to show as much as possible what the true scene was’.12 The ability to make pornography, and to exhibit it legally, to perform in it and consume it, these were not expressions of exploitation and abuse but a means through which to represent gay life. It is worth remembering that gay liberation is also sexual liberation, freedom from the shame and guilt of being gay and porn once represented an act of self-affirmation and defiance in ways which seem impossible to argue for in the context of heterosexual pornography and subsequently in the industrial development of gay video pornography from the 1980s onwards. Early examples of feature-length gay pornography such as Wakefield Poole’s Bijou (1972) and Fred Halsted’s L.A. Plays Itself (1972) are in fact closer in spirit to underground cinema, like Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1964) and Andy Warhol’s My Hustler (1965), especially in their homoerotic visuals, experimental and avant-garde film techniques. Activist and writer Patrick Moore even suggests that we understand early gay pornography and sexual practice as a form of gay art, discos being the theatres of sexual experimentation, and that as gay men we ought to re-contextualise our sexual cultures as sources of artistic creativity and heritage.13 While I agree with Moore and fully align myself with his radical politics of anti-shame, I would caution against fully equating gayness in sexual terms; yet, it must be noted that one of the most potent strategies of gay politics was to make gay sex and sexual culture visible, the antidote to shameful, hidden and closeted versions of gayness.

The construction of filmic space is an essential difference between gay and straight porn; the spaces of gay pornography are not solely within the realm of fantasy as they often are in heterosexual porn. In A Night at the Adonis one could actually be in New York’s Adonis theatre watching the very film in the space of the film itself; a sort of spectatorial mise-en-abyme. The hetero-spatial tropes of the doctor’s office, the college dorm, the school classroom, the roller rink, are straight porn fantasies that transform mundane public spaces into carnal localities and stand in contradistinction to the very quotidian spaces of gay life and leisure which are self-reflexively documented and self-affirmative in nature.

FIGURE 4.2 Soundtracks to the sexual subculture: recreating the disco scene in A Night at the Adonis

Cante and Restivo refer to a ‘mandate toward spatiality’14 in gay porn and I would add that, importantly, the soundtrack and disco also give equal meaning to porn not just as a visual spatialisation of place and pleasure but an aural spatialisation too. The soundtrack that accompanies the visualising of space and the representation of sex in A Night at the Adonis is pure disco heaven; discophiles will recognise Tuxedo Junction’s version of ‘Moonlight Serenade’ (1978) and THP’s ‘Two Hot for Love’ (1978).

There are three points worth teasing out here in relation to the disco soundtrack and the way it represents some conventions of sound practice in gay films from the period. Firstly, the structure of the music often determines the organisation of the sex scene and the climax sometimes comes through the music rather than the image of ejaculation, that is, the climax is heard rather than seen. Secondly, this often means that the sequential logic of the sex is displaced on to the formal structures of the music rather than performance, determined not by the conventional linear logic of straight pornography: foreplay; oral sex; penetration; the definitive use of ejaculation as scene closure. Thirdly, in A Night at the Adonis there is more of a montage structure to the sex scenes; they are fragmented, often unfinished or begun in media res, they are subject to parallel editing with lengthy non-sex scenes, and one can observe how continuity tends to be maintained not through the ordering of sex and bodies (since gender is not the disparity here) but rather sex gets ordered through the structure of the music heard; a seamless filmic experience is constructed through sound rather than image.

In a reversal of this cinematic convention in which sound proffers continuity on the image, the organisation of disco music in ‘Two Hot for Love’ turns out to be structured as a linear sexual encounter; the music is ready made for porno. The A-side of ‘Two Hot for Love’ heard in A Night at the Adonis is a blissful fifteen minutes that is listed on the record label as follows:

A1. Two Hot For Love

Four-Play / 3:05

Excitement Part 1 / 5:11

Excitement Part 2 / 2:50

Climax / 2:10

Resolution / 2:35

The efficacy of disco to fashion itself through sexual tropes cannot be overstated here. The classical music convention of organising the music as a suite is rendered wholly in sexual terms, a sexualisation of the classical, thus making audible and legible relations between sex and music or rather disco and pornography.

FEELING MIGHTY REAL: SOUNDS, LYRICS AND PORNO CROSSOVERS

Two Hot For Love is just one of hundreds of disco songs which use sexual language, metaphors, kinky allusions and straightforward smut. Disco constantly employs the word funk as a synonym for fuck that in disco-style singing allows the two terms to sound almost homophonous. For example, Sylvester’s ‘Do You Wanna Funk’ (1982) or Giorgio Moroder’s ‘I Wanna Funk With You Tonight’ (1976) make no claim to be anything but songs about the invitation to fuck. In Moroder’s track we have a typical call and response situation when the male voice sings ‘I wanna funk with you tonight’ and the susurrus tones of the female voice returns with ‘yeah baby, lets funk tonight’. Obviously these moments have to be heard for their full effects. It is also worth reminding the reader that the original African-American vernacular term funk once referred to the smell of sex on the body. Along with stimulating lyrics there is a good deal of (predominantly) female performers oohing and aahing in disco music as concrete vocalisations of sexual pleasure. These ‘bird calls’ are often identical to the vocalisations you can hear in the post-dubbed porno soundtrack that Linda Williams suggests are the ‘prominent signifier of female pleasure, in the absence of other, more visual assurances’.15

Patriarchal and anti-feminist anxieties around disco music were often couched in concerns that disco music was obscene in its sexual suggestiveness. Clearly an attack on female sexuality qua independence expressed in terms of a pleasure without men. Disco was central in reifying the female orgasm through a popular music form. Donna Summer’s ‘Love to Love You Baby’ (1975) was a seventeen-minute orgasmic musical journey with the formal structure and texture of the music, stopping and starting, taking it slow, taking it fast, echoing the rhythm of a sensuous masturbation session. The B-side of Summer’s breakthrough hit was evocatively called ‘Need a Man Blues’ and the photographic cover of the 12” single showed the singer lying back in her feathered nightdress perhaps leaving us in no doubt about the ‘baby’ she was loving outside the frame. ‘Love to Love You Baby’ is the benchmark in disco ecstasy and the vocalisations of pleasure and climax were copied in countless other disco releases, some even more obviously pornographic such as Poussez’s orgasm workout ‘Come On and Do It!’ (1979).

The structure of the music in ‘Love to Love You Baby’, and in disco and dance music more generally, is firstly related to being taken on a affective musical journey, of getting taken somewhere by the music which is, secondly, understood in sexual terms as you lose yourself in the pleasure of the beat; we submit ourselves to the beat, becomes slaves to the rhythm. The crescendos and whooshing noises central to Summer’s disco sound created by Giorgio Moroder and the extensive pitch of her vocal range mean the music is full of intensity and upward movement; in fact, you really feel you are taking off, it gives a frisson, a tingle on the back of the neck. The effect of Summer’s disco is structurally equivalent to orgasmic tension and release, only the music here gives us multiple climaxes over and over again. The arrangement of intensity and upward movement of Summer’s ‘No More Tears (Enough is Enough)’ (1979), a duet with Barbara Streisand, when the vocals soar and the beats kick in, is as close to ecstasy as one might ever get through music. The transcendence associated with disco offers such an experience; according to John Gill in Queer Noises (1995)16 dance music in general is one that closely corresponds to Roland Barthes’ concept of jouissance.17 Through jouissance we surrender and give our body over to unconscious experience as a deeply-felt restorative bliss takes over and returns us to pre-subjective rapture. The aesthetics of disco, letting the body be overcome with music, the hot and sweaty dark space of the disco itself, indicates those moments at which jouissance takes hold in the upward scales of movement, the crescendos, the soaring vocals, the whooshing sounds and synthesizer pops, disco’s musical textures producing rapture and bliss. Disco tells us what jouissance might sound like as if orgasms could be musical rendered. One is reminded here of the ‘Excessive Machine’ in Barbarella (Roger Vadim, 1968), a huge organ-like instrument whose effect is death by orgasm as music is played on the body. Andrew Kopkind writing in The Village Voice in 1979 writes that ‘a “hot” disco mix in a dance club is a sexual metaphor; the dejaay plays with the audience’s emotions, pleasing and teasing in a crescendo of feeling’.18 The ‘disco mix’ itself, often a remixed and reworked extension of the three-minute pop song, is imagined in sexual terms to be stretched out into a sensuous experience. The conventional musical form of pop is extended, manipulated and transformed from a radio-friendly ditty into a raunchy beat-throbbing crescendo-driven workout that asks us to feel the beat and ride the rhythm. Kopkind’s quotes one disco dancer who tells the deejay that ‘you were fucking me with your music! Do me a favour and fuck me again.’19

A number of erotically conceived disco songs also include raunchy dialogue and spoken sexual scenarios. The original thirteen-minute ‘Cruisin’ the Streets’ by Boy’s Town Gang, works both as a form of gay tutelage and an aural porn experience; the track tells you how to cruise and where to cruise. This is an important song released in 1981 by the San Francisco record label Moby Dick Records who along with the Megatone label shaped the synthesizer-led HI-NRG ‘gay sound’ central to the transition from 1970s disco music into 1980s dance music. ‘Cruisin’ the Streets’ is sung by Cynthia Manley, in the role of a sassy street walker, who tells the listener:

You can find anything you might be lookin’ for

You might find a big boy nine inches or more

Listen I promise you it might make you sore

Absolutely guaranteed it won’t be a bore

Following such licentious rhymes, about seven minutes in, we are treated to a rather cinematic moment. The sounds of the night, high heels clacking and cars passing, allows us to visualise through the music a pornographic scenario; two butch men’s voices exchange dialogue and pick each other up, while Manley asks to watch as the two men get off. Again lots of oohing and aahing, what Cante and Restivo refer to in film as ‘pornoperformative vocalizations’,20 for example, ‘oh yeah’ and ‘suck it’. The three-way is interrupted by a police officer (‘what are you fags up to?’) who is in turn accosted (‘up against the wall, you cunt!’) and sexually assaulted as the moaning of all four characters take over the music, mapping the orgiastic vocals to the structural crescendo.

The presence of a woman who sings instructions for the listener on how to cruise and also becomes an observer and finally a participant in the gay sex action described above; nothing out of the ordinary in the 1970s. If we link this female presence back to films like A Night at the Adonis or any number of disco-scored gay films one can observe that women are continually present only aurally rather visually. The sex scenes scored to disco mentioned in the previous films are often dominated by disembodied female voices; not only does sound confer continuity on the image through disco music but it also affords an agency to the female voice in a world visually dominated by men. Women are everywhere in gay porn albeit through the presence of disco music gesturing to a debate to be argued elsewhere on the sound politics of gay male/straight female relations.

The male singing voice is largely absent from gay pornography in the 1970s except in the few odd cases where the singer is known to be gay, queer and/or popular with gay audiences. For example, Boots and Saddles includes music by male diva Sylvester and the moustachioed Dennis Parker. As another point of connection between disco and pornography I should briefly recount Parker’s story here. He had one disco album with the biggest label, Casablanca, called Like an Eagle (1978), however, prior to his recording career Parker’s nom de plum was Wade Nichols and he featured in a number of gay porn loops. He also worked briefly in straight porn (for example Radley Metzger’s Barbara Broadcast (1977)), but Parker is better known for his roles in gay classics like Hand in Hand’s Boynapped (Jack Devau, 1975). His inclusion in the soundtrack to Boots and Saddles is clearly an homage.

The porno/disco crossover was not unique to gay culture although it was certainly forged there. One of the most commercially successful disco songs of all time is Andrea True Connection’s ‘More, More, More’ (1976). Andrea True was a porn star with Avon Films but unlike Parker she did not hide the fact, even singing about it. The lyrics of ‘More, More, More’ include the lines ‘get the camera’s rolling, get the action going’ and explicitly quote her adult film career. More shockingly, Andrea True was part of the Avon film company along with Annie Sprinkle in films that were notorious as the nastiest, roughest and most horrific of all commercially released straight pornography. They also made a few ‘vanilla’ films, Sex Rink (Ray Dennis Steckler, 1976) and Plato’s Retreat (Ray Dennis Steckler, 1979), set in a disco-related roller-skating contexts, no doubt an inspiration for Heather Graham’s roller girl in Boogie Nights (Paul Thomas Anderson, 1997). Avon films were used as the most heinous examples of the porn industry, the benchmark of depravity during the federal investigation of pornography in the US known as the Meese Commission. ‘More, More, More’ is quintessential disco, originally remixed by Tom Moulton, but the song’s longevity has allowed it to survive as a classic played by mobile deejays, heard at office parties, in pub discos, stuck on cheap compilation CDs; versions of the song have been used for shampoo adverts, and its been covered by pop acts Bananarama and Rachel Stevens, all with little knowledge of its seedy origins.

Sex still sells dance music but with one caveat; women are being exploited rather than celebrated in a cultural context that is imagined through sexism rather than liberation. The commercial end of dance music has become the locus for a laddish pornographic imaginary as any number of worthless compilations, mix-CDs and cheap videos feel it necessary to package the music through soft-porn images of the female body; it’s even sold to female consumers this way. I find it depressing that the origins of dance music in disco have been visually co-opted upon such unequal terms, so much so that the work of woman and gays as consumers, producers and artists is erased and hidden behind the solicitation of male fantasy.

Disco was a democracy of eroticism that favoured both sexes and sexualities in equal measure. Richard Dyer famously defended disco in 1979 referring to it’s ‘whole body eroticism’21 in contrast to the cock-centred logic of rock with its hip thrusting and phallic iconography. For Dyer ‘disco restores eroticism to the whole body’22 but with the contemporary mainstreaming of dance music we are witnessing a reversal of this politics in which the apparent sexiness of the music becomes dependent on a commercial imperative that only objectifies the female body. The marketing images and artwork of disco in the 1970s conveyed a very different set of sexual politics. Images of the female body, the male body and obvious gay iconography were everywhere. Already mentioned, the sleeve of Donna Summer’s ‘Love to Love You Baby’ shows the singer lying back and, we assume, pleasuring herself. There is no solicitation of the gaze here; this is an introspective scene of desire between self and music.

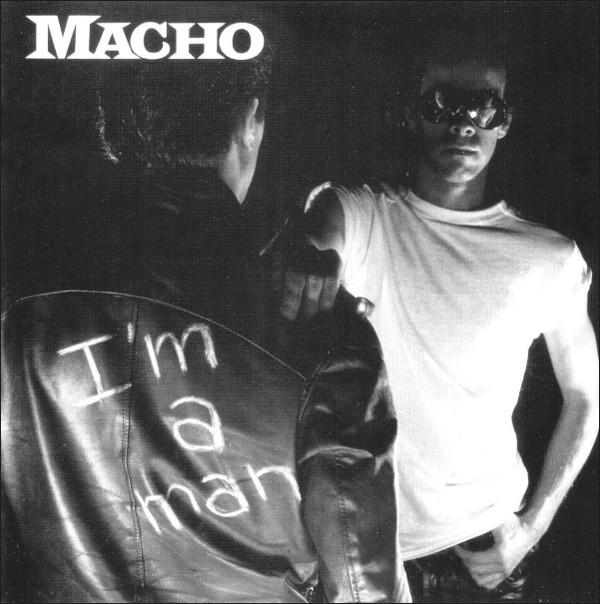

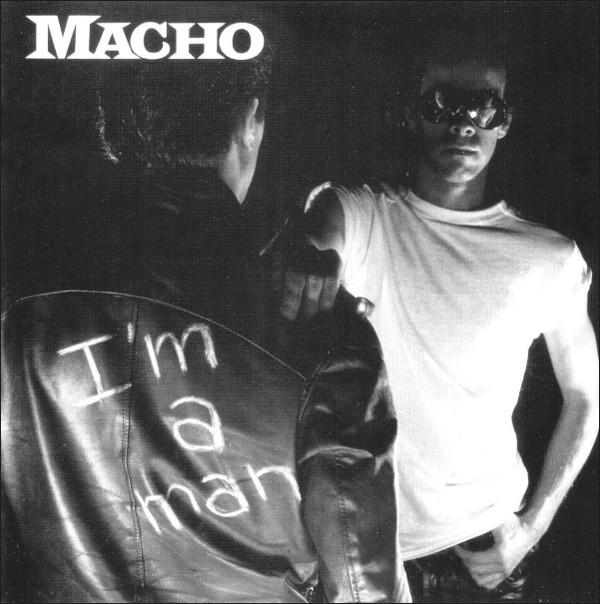

FIGURE 4.3 Looks between men: creating the homoerotic gaze in disco marketing

FIGURE 4.4 Pornographic mise-en-scenes and music: the 1981 cover to Disc Charge

The Playboy come-hither look emanating from the eyes of models, the standard of a need to legitimise the look by invitation, adorns a great deal of the marketing of contemporary dance music as I have suggested. However, in classic disco iconography, the structures of looking were often organised between men. The sleeve of Macho’s I’m a Man (1978) is a classic in terms of gay iconography (leather jackets, white t-shirts, aviator sunglasses) and the looking relay of cruising. The sunglasses of the man facing us, reflect both the man in the black leather jacket, with the album title chalked on his back, but upon a closer look we can also see in the details the reflection of a naked torso, a man waiting outside the frame for some three-way action. The reverse side of the sleeve is an intimate close-up of a hairy chest with the credits overlaying the image. The sleeves of both Revanche’s Music Man (1979) and the Boy’s Town Gang’s Disc Charge (1981) also present us with pornographic mise-en-scènes; the settings here are a garage and a pier. The imagery includes half-naked motor mechanics, greased up and ready for action; Music Man features sailors and military men waiting for sex, and in true democratic fashion a woman is joining in on the action.

In conclusion, the legacies of disco and gay pornography as tenets of 1970s culture need to be properly contextualised in terms of their impact on the formation of sexual identities through the pleasures of popular culture. Certainly, from the perspective of queer studies and gay history, the original disco culture has to be continually reclaimed, rediscovered, canonised, for its inspirational models of life that remain benchmarks of a 1970s gay ontology. Disco and pornography were the nexus of a liberating experience for queers and, to echo Patrick Moore here, ‘as a gay man who missed those years, I refuse to abandon their memory’.23 Furthermore, examining the relationship between disco as a popular form of music and leisure in the 1970s and its salient connections to pornography and gay culture hopefully reconstructs the period in ways which challenge the contemporary solipsistic and pejorative definitions of disco, in other words, bringing sexy back.