With a bizarre back catalogue which repeatedly fused elements of sexual excess with punishment and humiliation, the late Italian exploitation director Joe D’Amato (real name Aristade Massachessi) can also rightly claim the label of being a ‘Sadean’ filmmaker. This definition is applicable not merely because much of D’Amato’s output circulated within the domain of the ‘pornographic’. Rather, it is the fact that his narratives were marked by a type of cross-generic overload, which combined outrageous doses of sex and horror in an appeal to different ‘grindhouse’ audiences. The extreme nature of many of D’Amato’s crossover productions can be inferred by a brief consideration of some of his most notorious titles. These centred on macabre depictions of sex which saw zombies attacking Westerners with monstrous phalluses (Porno Holocaust (1979)), as well as voodoo priestesses castrating their lovers at the point of orgasm (Erotic Nights of the Living Dead (1980)). Other outrageous scenes of sexual trauma that D’Amato concocted included those featuring repressed taxidermists seducing young women in the same bed as their dead brides (Beyond the Darkness (1979)), as well as sexually charged couples who copulate before images of filmed female mutilation (Emanuelle in America (1976)).

What united all of these productions was D’Amato’s unflinching fusion of sex and gore. This clearly drew on Sade’s favoured combination of eroticism and violence, to the extent that the boundaries of sexual desire and displeasure were dissolved. For instance, writing in Sade: The Libertine Novels, John Phillips has defined works such as 120 Days of Sodom as dominated by ‘a criminal orgy of sexual deviance protracted well beyond the normal limits of human endurance’.1

At the level of film form, D’Amato’s fusion of disparate generic elements also affected the logical structure of his works. These were marked by a repetitious, meandering and often illogical structure that frequently outraged many of the director’s detractors. However, these strategies also recall the contradictory nature of narrative excess and deviation found in Sade’s work. As Maurice Charney has noted, ‘Sade’s gargantuan sexual imagination is not intended to provoke or inflame desire; rather the vast repetition has a numbing effect’.2 It is precisely such a numbing effect which accompanied the erotic and macabre crossover imagery in Joe D’Amato’s cinema.

While the Sadean influences can be found in both the form and content of D’Amato’s delirious 1970s productions, little comment has been made on the 35mm hard-core films with which he became involved from 1994 until his death in 1999. For many, these glossy, ‘feel good’ porn productions (whose titles included X-Hamlet (1994), Barone Von Masoch (1994) and Tarzan-X Shame of Jane (1994)), seem to share little connection with the director’s earlier, controversial output.

However, by considering two of D’Amato’s later porn titles: 120 Days of the Anal and The Marquis De Sade (both 1995), I wish to show an essential Sadean continuity between these texts and the director’s earlier infamous output. It is not merely the fact that these two films take the figure of Sade and his philosophy as their focus, rather they retain the director’s interest in emphasising the horrific nature of sexuality, while also presenting these images in a convoluted and repetitive narrative form. In order to identify these features, I want to firstly offer a case study drawn from D’Amato’s 1970s output before considering its links to his later hard-core productions.

SADEAN SEX IN THE 1970s

Several of the Sadean thematic and stylistic structures for which Joe D’Amato first gained international exposure (and notoriety) are evident in his 1976 film Emanuelle and Françoise. This production recounts the (literally) fatal coupling between a manipulative womaniser named Carlo (played by D’Amato’s scriptwriter/acting regular George Eastman), and two sisters: Françoise and Emanuelle. The narrative is organised around a number of disorientating flashbacks that detail the catalogue of sexual humiliations forced upon the virginal Françoise (Patrizia Gori) by Carlo, resulting in her eventual suicide. These fatal actions are later revealed to the more sexually liberated Emanuelle (Rosemarie Lindt), in the form of a suicide note penned by Françoise before she jumped to her death under a speeding train. The document reveals that Carlo forced his lover to appear in pornographic movies against her will (as well as coercing her into sexual encounters with a number of his business associates). It thus becomes the trigger upon which Emanuelle plots a violent revenge against the male protagonist.

After orchestrating a meeting with Carlo, the heroine manipulates his sexual interest in her, inviting the protagonist to her home with the promises of seduction. Emanuelle then drugs Carlo and when the protagonist awakens, he is revealed as being imprisoned behind a two-way mirror. From this position of incarceration, Carlo is forced to watch Emanuelle engage in a number of sexual liaisons with male and female partners (including his current girlfriend Mira).

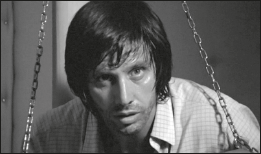

FIGURE 6.1 The anguish of voyeurism: Carlo as the incarcerated viewer of Emanuelle’s revenge

Via the heroine’s revenge plot, Emanuelle and Françoise renders the thrill of sexual excess and display as a source of humiliation and trauma. Not only does Emanuelle proceed to starve, torture, threaten to kill and castrate her captive, but she also uses drugs to further disorientate and terrorise him. For instance, one hallucinogenic scene features Carlo imagining that he is witnessing a refined dinner party that ends in a bizarre cannibalistic orgy with the diners feasting on severed human limbs.

In its theme and arrangement, Emanuelle and Françoise embodies many of the traits of Sadean fiction as described by critics such as Maurice Charney. For instance, its separation of female protagonists into virginal and sexual types clearly recalls Sade’s classic division of virtue and vice in the duel female figures of Justine and Juliette, with the distinction between regimes of sexual power (and powerlessness) that this implies. Indeed, Carlo’s exploitation of the emotionally scarred and vulnerable Françoise is juxtaposed and contrasted with his own manipulation by the erotically charged Emanuelle. This division between virgin and vamp draws parity with the distinction that Charney makes between ‘Justine’s virginal passivity and Juliette’s sexual terror’.3

D’Amato even manipulates the film’s convoluted narrative structure as a way of drawing distinctions between his two heroines. For instance, the opening credit scene of the film reveals Françoise stripping confidently before a cameraman in what appears to be a consensual ‘glamour’ photography shoot. It is only the later discovery of the heroine’s suicide note that reveals Carlo’s coercion of the protagonist into these pornographic scenarios against her will. Carlo’s treatment of Françoise indicates in the words of Maurice Charney that ‘all sex in Sade is a form of tyranny, by which the dominant partner imposes his will on the subservient sex object’.4 This serves to distinguish the fate of the heroine from the subsequent actions of Emanuelle, who by subverting Carlo’s control over the sexual scenario places him in the very masochistic position previously enforced on her sister. Within the realm of Sadean aesthetics, the film’s constantly changing set of power dynamics indicates that all sexual relations ‘are sadomasochistic ones, with the possibility that roles can be temporarily changed for the purposes of experimentation’.5

However, it is not merely the oscillation between states of power and oppression that underlie the Sadean impetus in Emanuelle and Françoise. Rather, it is the film’s very obsession with seeing its protagonists perform the sexual act that translates its erotic acts into scenarios of theatrical display. Here, sex is relocated from a private into a public act, echoing what John Phillips has termed the essentially ‘public and theatrical’ nature of Sade’s writing.6 As with novels like The 120 Days of Sodom,7 D’Amato’s film produces sexual activity staged before an audience, the outcome of which is liable to evoke a number of contradictory and uncomfortable emotions.

This capacity for erotic satisfaction to be transmuted into a scenario of suffering is indicated in the film’s opening segment. Here, a montage sequence offers the illusion of a content Françoise shopping for a variety of gifts for Carlo on her way home from the glamour photography shoot. Although these scenes establish an up-beat theme to the proceedings, they are suddenly disrupted when she arrives home to discover Carlo making love to another woman. Watching the erotic encounter through an open door, Françoise adopts the position of the classic D’Amato voyeur: a protagonist whose obsession with looking overrides the traumatic potential for what is actually viewed. During the scene, the camera pans between Françoise’s horrified gaze, Carlo’s erotic coupling and a small statue that adorns a bedside cabinet. This monument, with distorted features and oversized, leering eyes in many respects echoes the near-monstrous status that D’Amato gives his voyeurs in the film. Indeed, if it is the case that D’Amato’s ‘lookers’ assume a fatalistic and masochistic position, then this structure finds its logical conclusion in Carlo’s positioning as the bound/tortured voyeur in the final stages of the film.

While this rendering of sexual activity as a site of public spectacle provides a motivating principle for Emanuelle and Françoise, it also constructs a point of traumatic repetition around which the narrative revolves. Although the heroine dies within the first five minutes of the film, her suicide note effectively keeps her alive, as well as prolonging her past-tense suffering via a series of extended flashbacks. These shifts in filmic time add to the narrative’s already convoluted structure, much to the confusion of many of the film’s contemporary reviewers. For instance, David Badder derided the structure of the narrative as ‘deadly dull’; concluding that it was guaranteed to send the bulk of its ‘frustrated audience into a deep sleep long before its predictable dénouement’.8

It is precisely because of these criticisms, that the structure of D’Amato’s film can be viewed within the Sadean tradition. Here, narrative structure is used as a form of experimentation, duplication and deviation that frequently works at odds to the erotic impact that the content attempts to create. Writing in Sade: The Libertine Novels, John Phillips has noted that the repetitive and self-referential comments about how the libertine orgies of The 120 Days of Sodom are being staged and executed produces a diminishing of ‘erotic impact on the reader’.9 As Phillips comments:

Overall… Les 120 Journées functions inefficiently as a work of pornography since, as we have seen, the reader’s interest is constantly displaced from any erotic effect to the ways in which sexuality is represented through linguistic, arithmetical and other formal structures.10

While the unsettling combination of titillation and trauma packaged in a monotonous, alienating form link D’Amato’s 1970s work to the effect that Phillips describes, these features are also present in the director’s later hard-core productions which deal explicitly with the figure of Sade and his ideas.

LUST IN A LOOP: THE ROLE OF REPETITION IN 120 DAYS OF THE ANAL

An Italian/American co-production, 120 Days of the Anal appears as the more ‘restrained’ of the two Sadean films that D’Amato completed in 1995. The film translates Sade’s victimised heroine Justine into the figure of Martine, who is imprisoned and molested by a group of lusty servants in the opening scene. Her fate is secured by the sudden intervention of an unnamed libertine (played by porn icon Marc Davis). The hero persuades the assembled males that their erotic satisfaction will be heightened through their victim’s compliance, arguing that he will be able to ‘seduce’ her into submission with tales of the libertine orgies he has organised. At first, Davis’s plan is greeted with derision, with one of the assembled males sneering that one ‘cannot fuck with your eyes’, after being asked to assume the position of voyeur.

While Martine’s gradual and increasingly sexualised writhing convinces the crowd of the libertine’s scheme, it also underscores the fact that any subsequent erotic ‘adventures’ will be premised upon the unpalatable outcome of her impending abuse. While the more disturbing aspects of the libertine’s plan are softened by the ‘consensual’ nature of the film’s pornographic motifs, it also functions as a basis of sexual trauma upon which the narrative continually returns. Equally, in Davis’s re-organisation of the male crowd into a gathering of sexual gazers, the film demonstrates the centrality of voyeurism and exhibitionistic display within the Sadean setting. For Maurice Charney, in these scenarios, ‘sex is theatricalised in Sade, and the orgy is his most natural form of sexual experience’.11 This point is demonstrated through the several flashback scenes through which Davis recounts his debauched past.

Here, at least two of the four extended sex scenes play upon vision (and indeed a lack of sight) as being a precursor to erotic excitement. For instance, the second flashback scene features a group of masked men who have to guess the identity of their female sexual partners by the smell of their body fluids, before an orgy ensues. Equally, the third flashback sequence features a hooded female who is at first offered to the assembled male libertines before being ravished by the group’s well-endowed black servant. During the sequence, D’Amato’s camera appears as if concealed behind plants and bushes (before focusing more fully on the sexual acts depicted), a strategy that once again underscores the voyeuristic potential inherent in the libertine regime.

FIGURE 6.2 Titillating and traumatic repetitions: sexual ‘looping’ in 120 Days of the Anal

Even when the film is not shifting its male and female protagonists through regimes of voyeurism/concealed sight, the impetus to look is central to the staging of the sex scenes as a sight of public spectacle. For instance, one of the final flashbacks from 120 Days of the Anal features a female engaged in an act of masturbation before the libertine crowd organised in a circular pattern around her. As the scene unfolds, Davis and his black servant join her in an act of vaginal and anal intercourse. Rather than enter the coupling, the rest of the assembled group find gratification in their roles as voyeurs, leading to several shots of male and female self-pleasuring. Through these scenes, 120 Days of the Anal confirms Sade’s view of the erotic act as a communal affair. As Phillips has noted, for Sade ‘debauchery here is above all a shared activity in which to be seen is as important as to see’.12

In its use of features such as the traumatic basis of sexual activity, as well as a voyeuristic obsession with erotic events, 120 Days of the Anal draws clear connections with not only the philosophy of Sade, but also the earlier output of Joe D’Amato. The film’s connection with both of these sources is also confirmed through the repetitive shifting between the flashback and present-tense scenes that make up the structure of the film. 120 Days of the Anal is constructed around four key flashback scenes, which are alternated with shots of Martine’s increasing sexual frenzy as Davis recounts the tales. What is noticeable about this structuring process is the way in which duration alters to mirror the heroine’s increasing sexual excitement. While the first two flashbacks are of similar length, the final ones occupy a much shorter time-span, being fragmented by D’Amato’s brief return to Martine’s approaching sexual climax.

However, if the structure of the film is constructed around the frenzied drive towards orgasm, this does not necessarily guarantee the sexual release and satisfaction that the term may imply. Rather, it condemns the viewer to a type of formal alienation, similar to the effect that Phillips has identified in Sade’s writings. Here, the constant alternation between differing cinematic tenses robs the spectator of the necessary temporal (and frequently visual) anchors from which to secure a position of gratification. If this is a result of the repetitive and convoluted form in which sexual activity takes place, then its disengaging effect is heightened by the way in which D’Amato frames the sexual activity of the libertine’s recollections. Whereas Martine’s sexual excitement is shot from an overhead position (allowing the viewer access to the whole of her body), the libertine encounters are framed in such extreme close-up that a ‘genital vignette’ replaces total, human interaction.

Via this method, the camera gazes in extreme proximity on a succession of penis, vagina and anus shots, which prove more alienating than arousing to the viewing eye. This is particularly marked in the ‘group’ encounters that dominate the first two flashbacks. Here, the camera frequently switches between differing sets of sex organs without identifying their respective owners. In so doing, D’Amato’s film provokes a curious barrier between the audience and the sexual excesses it depicts. This provides a visual equivalent of the ‘de-realising’ effect that Phillips has identified in Sade’s literary works. Here, textual complexity and ambiguity ‘focuses attention on process rather than erotic content’.13

TITILLATION AND TORTURE: ROCCO AND HIS BROTHER

With 120 Days of the Anal, Joe D’Amato gestures towards the repetition of traumatic/sexual encounters that were evident in his 1970s productions. His 1995 companion piece The Marquis De Sade makes these links even more explicit, by taking Sade’s own incarceration as its central subject matter. In many respects, the film shares the complicated formal structure of the director’s earlier works such as Emanuelle and Françoise. Here, Donatien’s fall from grace is depicted within a series of extended flashbacks that are fragmented by sudden (and often unmotivated) shifts in filmic tense.

From the outset, D’Amato makes good use of a doubling motif to initiate the flashback sequences. Here, the imprisoned Marquis finds his past actions challenged by an imaginary incarnation of himself. Both Sade and his chastising double are played by the famed Italian porn stud (and D’Amato regular) Rocco Siffredi.

This iconic male performer gained exposure on the adult circuit for not only the excessive size of his penis (as well as its ejaculating capacities), but also his well toned, body-building physique. However, in contrast to his usually fine-tuned appearance, D’Amato casts him here as a gaunt figure who is wracked by the demons of his past.

As with D’Amato’s earlier incarnation of the voyeuristic Carlo from Emanuelle and Françoise, this is a figure whose reflections and sexual obsessions are a source of displeasure rather than guaranteed sexual satisfaction. The traumatic basis to the protagonist’s malaise is indicated in the film’s first flashback, when the Marquis’ double asks him to recollect ‘his first discovery of the female sex’. The flashback that follows features the camera adopting a point of view style, whilst concealed within a closet. From this position, a subjective perspective is given watching a young maid disrobe. When the illicit gazer (revealed as a childhood Sade) is discovered, it is interesting to note that it is the camera lens itself that is directly reprimanded, being beaten and shaken by the semi-naked woman. Thus it can be argued that it is not only the protagonist, but also the viewer (beyond the limits of the film frame), who come to share Sade’s humiliation. Such images confirm that in the Sadean universe, sexuality is linked to despair and mistreatment rather than physical liberation. According to Charney:

Sade is a spokesman for hard and difficult sex, violent, cruel and energetic. Orgasm unites man with the animal creation and is a kind of epileptic fit or temporary seizure by which we abandon all pretensions to reason and false enlightenment. Against a benevolent and optimistic romanticism, Sade opposes a negative, primitive, chaotic and destructive view of the sexual relationship.14

Although the later flashback scenes recounting the activities of the adult Sade show him in a dominating position over his varied female partners, they must be premised upon the initial scene of violence and humiliation enacted against the protagonist (as well as the character’s torment from his imaginary divided self in the present-tense scenes punctuating these sexual encounters). Indeed, the lyrics of the film’s theme tune ‘Love and Pain’ that accompany each of Sade’s adult sexual encounters reiterates the connection between eroticism and displeasure that the film is trying to create. Equally, even those scenes which feature Sade orchestrating the sexual humiliation of others feature an act of voyeurism on the part of an aroused on-looker, thereby connecting them with the perils of voyeurism identified in D’Amato’s earlier work.

FIGURE 6.3 Rocco and His Body: the male porn star as phallic icon?

An example of such a scenario can be found in the second flashback scene featuring the adult Sade. Here, Renee (the Marquis’ future bride), conceals herself and watches with a mixture of passion and disgust as the libertine coerces a prostitute into a series of couplings that are intended to degrade. Firstly, Sade attempts to placate his new conquest with promises of gold coins, before making her crouch down and urinate over the reward on offer. When her bladder skills are revealed as too inadequate to arouse the libertine, he gestures the prostitute towards an act of oral sex before urinating over her face and hair.

The anal sex scene between the pair that follows retains these overtones of violence and sexual oppression. Firstly, Sade enters his partner roughly from behind before threatening to ‘rip your guts out’. The extended scenes of anality that follow are similarly coded within a vocabulary of disgust. Here, the libertine claims that he will slice his partner’s ‘ass open’ as well as ‘pull the shit out of her’. (The violent language of eroticism demonstrated in this scene is evident in an earlier coupling between Sade and two women, where the protagonist derides his partners with terms such as ‘bitch’, ‘whore’ and ‘pig’). The sex scene ends when Sade reaches a sexual climax while attempting to use his penis to choke this partner at the point of orgasm. In many respects, this body fluid-dominated sex scene draws comparison with some of the more extreme orgies enacted in 120 Days of Sodom, including:

other transgressive acts … promptly enacted by the libertines include urine-drinking, armpit smelling, saliva swallowing, fart swallowing, nostril licking, the drinking of menstrual blood, and of course, fucking.15

Arguably, the power behind these otherwise offensive scenarios lies in the ability to use the body (and its waste products) as a way of introducing an element of displeasure into an otherwise titillating scenario. As already noted, this feature is a long established trait in D’Amato’s films. In The Marquis De Sade, the strategy of rendering pornographic ‘thrills’ distasteful is most marked in the sequence where two women are blindfolded before being required to arouse an unidentified suitor. Although Sade informs his sightless assistants that they are ‘licking the body of a young athlete from head to foot’, when their vision is restored they are as disgusted to find that they have been cavorting with an overweight, deformed, middle-aged servant. Although the women verbalise their displeasure upon this discovery, and even struggle against nausea at the sight of the servant’s dwarfish genitals, Sade coerces them to a climax with this unlikely partner. Here, the pleasure of sexual release is overburdened by a sense of decay and disgust. This once again mirrors the literary source material upon which D’Amato draws. As Phillips has noted, rather than just offend the senses, Sade uses such repulsive imagery to invert ‘aesthetic norms, replacing the sweet fragrances of youth and beauty with the foul smelling and ugly as a basis of sexual attraction’.16

FIGURE 6.4 Abjection and eroticism: body fluids and fluid body boundaries in The Marquis De Sade

TITILLATION AND TRAUMA: ROCCO AND HIS BODY

Through their traumatic rendering of sex with violence, degradation or implied threat, the later films of Joe D’Amato can be aligned with the Sadean impetus that defined his most infamous output of the 1970s. These texts also display the Sadean obsessions with voyeurism and erotic exhibitionism that defined works such as 120 Days of Sodom. Equally, the formal structure of D’Amato’s works, with their emphasis on repetition and deviation can be seen as similar to the narrative experiments that critics such as Phillips and Charney have identified in Sade’s fiction.

It is also worth considering the extent to which this overlap between titillation and trauma might affect depictions of masculinity within a format that has traditionally been seen as gratifying male desires. Writing in the volume Running Scared: Masculinity and Representations of the Male Body, Peter Lehman has noted that the conventions, motifs and modes of depiction within mainstream heterosexual pornography function to distinguish between the genders, while attributing erotic power to the male.17 This is seen in the frequency with which male characters function as unchecked voyeurs: they have visual access to the naked female body by watching from a secret location. Equally, as Lehman notes, by focusing on the male orgasm (or ‘money shot’) as a guarantor of sexual satisfaction, such genre conventions confirm that

Male sexuality lies at the centre of the porn genre. Everything turns on affirming and satisfying male desires and the hard-core scene typically ends immediately after the visual proof that this has occurred. Women’s pleasure becomes merely a sign of their dependence on the phallus.18

By fusing sex with violence, threat and disgust, both Sade and D’Amato’s work can be seen as reversing many of the male-centred conventions of pornography. From Carlo’s status as impotent, imprisoned gazer in Emanuelle and Françoise, to the beating attributed to the visually curious youngster (and viewer) in the opening of The Marquis De Sade, these works introduce a generically uncharacteristic degree of punishment associated with male voyeurism. Alongside this denigration of gendered looking, D’Amato reverses the ‘invisibility’ often associated with modes of male display in such formats.

While it is true that women still occupy a position of visual spectacle in both his early and later erotic dramas, it is noticeable that their exhibitionistic role is in fact superseded by an obsessive focus on the male body. An example of this strategy can be seen in the first flashback featuring Rocco Siffredi as the adult Sade. Here, the protagonist is depicted as bathing while being secretly watched by two giggling chambermaids. When the females are discovered, they are invited to join the bather and an orgy ensues. What is interesting about the sexual acts that unfold here is the way in which the camera glides over the images of the females undressing (traditionally the focus of such porno explorations), coming to rest instead on shots of Sade’s penis and buttocks. The scene echoes a similar focus on male exhibitionism found in 120 Days of the Anal. For instance, during the libertine’s first flashback recollection, the camera retards its focus on disrobing females in favour of extended shots of the muscular body of the black servant who comes to visually dominate the scene.

Rather than representing an isolated example, it can be argued that a visual obsession with Siffredi’s body dominates both this sex scene as well as the other erotic encounters in The Marquis De Sade. While it is not uncommon for such iconic (and well-endowed) male porn performers to attract a high degree of visual interest, these strategies of display work in opposition to the normal conventions of masculine display within pornography. As Lehman has noted, when reduced to a site of naked spectacle, images of masculinity evoke a number of contradictory (and potentially threatening) emotions in the heterosexual male. As a result, these have to be minimised by anchoring such scenes of exhibitionism to the primary goal of servicing the depicted females. Here, as ‘women desire the visibility of male ejaculation, they frequently express their desire for large penises’.19

In contrast to these ‘traditional’ uses of the male body in porn, D’Amato’s depiction of Siffredi connotes a high degree of sexual ambiguity that denies the male viewer a stable point of masculine identification. These sexual tensions are evidenced in the scene where an experienced lesbian inducts a younger woman into the pleasures of same-sex copulation, which she claims requires a rejection of ‘the strong, muscular arms of a male’. After informing the sexual novice that Sade’s new maid will be joining them, an unidentified ‘woman’ appears and is initiated into the coupling. However, as the pair begins to disrobe the dress of their new partner, they are surprised to find that is in fact Sade, who has disguised himself as a woman in order to join in the encounter. He then proceeds to initiate intercourse while still wearing his ‘female’ wig, earrings, corset and heavily rouged face. This scene indicates just one way in which D’Amato parodies the machismo associated with male porn stars. Another scene features a cameo by famed porn regular Christoph Clark, who is here cast as Sade’s camp cousin who leaves one of his host’s orgies after complaining that he can never get ‘himself any cock’.

FIGURE 6.5 Rocco and his body: the emphasis on male exhibitionism in The Marquis De Sade

Rather than being isolated to one specific production, these atypical masculine representations dominate all of D’Amato’s supposedly heterosexual hard-core works. For instance, a similar degree of feminisation happens to Marc Davis in the second flashback scene of 120 Days of the Anal. Here, D’Amato arranges the libertine in front of his (semi-naked) black servant during an encounter with an unidentified female. This close proximity between the two men gives the appearance of a scene of homoerotic coitus, normally shunned by mainstream heterosexual porn. While this degree of feminising the male ‘erotic icon’ is uncommon within the boundaries heterosexual pornography, it is characteristic of Sadean sexual ambiguity from which D’Amato draws his source material. As Phllips has noted, although novels like 120 Days of the Sodom abound with phallic imagery, these depictions of masculinity are frequently accompanied by a degree of sexual fluidity. For instance, he discusses the figure of the financier Durcet whom Sade has depicted as possessing ‘an incredibly small penis and the breasts and buttocks of a woman’.20

The degree of sexual ambiguity found in Sade and D’Amato’s work functions at the level of the iconic, whilst also affecting the way in which soundtrack connotes sexual pleasure. For critics like Lehman, although the soundtracks in porn productions are geared towards the vocalisation of female pleasure, they function merely as a response to the genre’s focus on dominant male desires. Here, ‘soundtrack editing further structures these moans to build with these visuals in a pattern geared to male sexual climax.’21 In contrast to these unambiguous anchors of male heterosexual activity, the soundtrack to works such as The Marquis De Sade is dominated by a type of male aural exhibitionism. This is exemplified by the high pitched screeching of Siffredi at the point of orgasm, or the effeminate squealing of his overweight, middle-aged assistant as he nears a sexual climax. These vocal gestures find parity with the construction of the Sadean heroes that John Phillips has studied. As evidenced in novels such as 120 Days of Sodom, these are libertines, who while gendered male, are seen to ‘shriek like banshees when reaching orgasm’.22 The evidence of these codes in the later films of Joe D’Amato, once again point to the way in which the filmmaker utilised the ideas and imagery of the Marquis de Sade to upset the patterns and presumptions within the pornographic text.