In 1976, over two thousand midnight moviegoers at the Los Angeles International Film Exposition (FILMEX) were treated to a film which a local journalist later described as ‘a raunchy, campy epic modelled on early Warhol efforts, those outrageous films starring Divine, the most static passages in Night of the Living Dead, and some of James Whale’s The Old Dark House with a little Tennessee Williams thrown in for leavening’.1 This 150-minute black-and-white epic, Thundercrack! (1975), contained non-simulated hard-core sex, and was written by noted underground filmmaker George Kuchar. The film was directed, photographed and edited by Kuchar’s former student, longtime artistic collaborator and lover, the thirty-year-old Curt McDowell. At the film’s intermission, half of the audience walked out of the auditorium.

Like the early films of John Waters, Thundercrack! is both an eccentric hybrid of several styles and genres of filmmaking and a highly illustrative case study of the rapidly-changing modes of film financing, distribution and exhibition in the mid-1970s. Also, all of these films were conceived by their makers as serious, if highly distinctive, moneymaking entries in the world of commercially-distributed feature filmmaking. But Waters’ Pink Flamingos (1972) slowly built a word-of-mouth cult following during its long midnight run at the Elgin Theater in New York, while Thundercrack! was turned down by Waters’ distributor, New Line Cinema, and was to enjoy only sporadic success at midnight screenings at the Roxie in San Francisco and at film festivals. Where the success of Pink Flamingos and Waters’ subsequent films are a testament to their maker’s almost Olympian insights into the relationship between transgression, sentiment and popular taste, the key to both the extraordinary artistic success and notable commercial failure of Thundercrack! is found in its dogged refusal to adhere to any coherent set of aesthetic categories or models of spectator engagement and pleasure. Also, the curious tale of Thundercrack! is as much a story of changes in the way independent and ‘cult’ movies were being financed, made and distributed as it is of the eccentricities of McDowell, Kuchar and company, which were considerable.

THE CULT OF CURT

Curt McDowell was born in 1945 in Lafayette, Indiana to ‘middle-class teetotalers named Donald and Harriet,’ he told The Advocate in 1977:

They were the perfect example of good Christian people with the perfect marriage and three perfect children, and I’m not sure to this day but what they are still the perfect family (sic.). My father always said, ‘Son, when you meet the girl that you can’t stand to live without, then that’s the girl you should marry.’ Well, I met him, and moved in with him in the winter of ’61, when I was 16. I told my family right away, as I have a passion for honesty, and good Christians that they were, they accepted it.2

The young Curt inherited from his mother a passion for family photography and intricately pasted and annotated scrapbooks. He also spent his time singing, writing music and drawing, first designing costumes for his little sister Melinda’s dolls, then eventually designing and sewing dresses for Melinda herself, endlessly drawing, painting and photographing the person to whom his diaries repeatedly refer as ‘the most beautiful girl in the world’.

Curt enrolled at the San Francisco Art Institute in 1968 on a scholarship in painting and studio art, ‘but by the following semester,’ he later recalled,

I was a confirmed filmmaker, stud[ying] with several influential filmmakers there, among them George Kuchar, James Broughton, Gunvor Nelson, Larry Jordan, and Robert Nelson. I was perhaps more prolific than careful and turned out fifteen or more films by the time I received my Master of Fine Arts degree in 1973.3

McDowell’s early films include A Visit to Indiana (1970), Confessions (1972) and Nudes: A Sketchbook (1974). Each in its own way documents their maker’s yearnings for family, friendship and erotic adventure, and many explicitly acknowledge the contributions of his mentor and lover, George Kuchar.

Kuchar, along with his twin brother Mike, had been one of the most important filmmakers in the 1960s New York underground movie scene. His short films were delirious, overheated parodies of Hollywood melodramas. Corruption of the Damned (1965), Hold Me While I’m Naked (1966), Color Me Shameless (1967) and House of the White People (1968) revelled in characters’ emotional breakdowns acted out by self-consciously ‘bad’ actors and helped to define an entire era’s Pop Art sensibility and ironic attachment to its cinematic past. Ensconced on the film faculty at the San Francisco Art Institute, George became a tireless and generous catalyst to generations of talented and iconoclastic filmmakers, none more iconoclastic than the satiric and satirical McDowell, whose Rabelaisian celebration of the carnal clashed head-on with the dour and paranoid artistic sensibilities of Kuchar.

Curt’s diaries from this period (and later) are filled with detailed accounts of his cruising adventures and amorous exploits, which fuelled his never-ending curiosity and creativity. In alimentary imagery cut from the same cloth as Thundercrack!’s screenplay, Kuchar later recalled that McDowell

was generous enough to share those memories with his audience, giving them what they secretly craved. The beefcake and cheesecake he dished out pumped blood into flaccid extremities, oozing life onto raincoat hidden laps. He believed in sex as a thing of celebration and many of his parties took on a wild flavor as he licked the candy canes of the revellers, lapping up cream-filled Ding Dongs while all the time guiding his own sensing organs into areas of dark delight and fudge encrusted wonders.4

In 1972, a year in which McDowell would complete no fewer than eight short personal films, he and his friend and collaborator, Mark Ellinger, formed Liberty 5 Productions to produce the sixty-minute commercial pornographic feature Lunch for a budget of $36,000, most of which was deferred and eventually covered by the film’s distributor, Unique Films. McDowell’s only feature film shot in colour, Lunch recounts the sexual goings-on in a San Francisco apartment complex and centres on the character of Gloria, played by the gloriously-named Velvet Busch, who is almost obsessively focused on the pleasures of fellatio. Ellinger contributed the musical score and a notable cum shot in his role as ‘Dave Powers’, and the movie played 16mm storefront porno houses for three years, yielding Ellinger and McDowell total producers’ shares of almost $10,000 apiece. The cheques arriving from Unique over this period enabled McDowell to cover some of his living expenses through the period of Thundercrack!’s writing and preproduction.5

The idea for Thundercrack!’s story came from discussions between Mark and Curt, who imagined a horror-porno-comedy which could be both a moneymaking proposition and a transitional work from the purely commercial Lunch to more eccentric and personal projects. In April 1974, the two sat on the steps of a park on Hyde Street and ‘worked out the general plot: one night in a thunderstorm, eight people thrown together by fate’.6 Kuchar acknowledged that the script he gave to Curt in early June had taken the movie in a completely new direction, recalling years later that Curt ‘thought of sex as sort of celebration or joyful union of things, and I always looked at it as a horror in people’s lives full of obsessions and stuff that they can’t control, and therefore the script was sort of colored in that direction’.7 This was to be the glorious alchemy at the heart of Thundercrack!: Kuchar’s anxieties and phobias would push classical horror movie conventions to the fore, while McDowell’s love of pansexual carnivalesque celebrate the very transgressions from which the classical horror film recoiled in revolted fascination.

(THUNDER)CRACKING THE CINEMATIC CODE

Thundercrack!’s convoluted and overwrought narrative concerns eight people who seek shelter from a thunderstorm in an isolated Nebraska farmhouse owned by the insane and alcoholic widow Mrs. Gert Hammond. The tweedy, pipe-smoking Chandler has picked up a hitchhiker, Bond, a working-class stud who senses both attraction and hostility from his host. Meanwhile, lesbian couple Roo and Sash pick up hitchhiker Toydy and his crate of stolen bananas. When Roo reaches into the back seat and grabs Toydy’s crotch, a jealous Sash grabs the wheel and the car crashes off the road. In the other car, Chandler grabs Bond’s crotch just as Wilene Cassidy knocks on the window to offer them autographed pictures of her husband, country singer Simon Cassidy. While Chandler and Bond go to investigate the explosion from the other car, Wilene walks to Gert’s foreboding mansion, Prairie Blossom, to ask to use the phone. Chandler and Bond arrive with the three survivors of the crash, and Gert invites them all to change clothes and stay for supper.

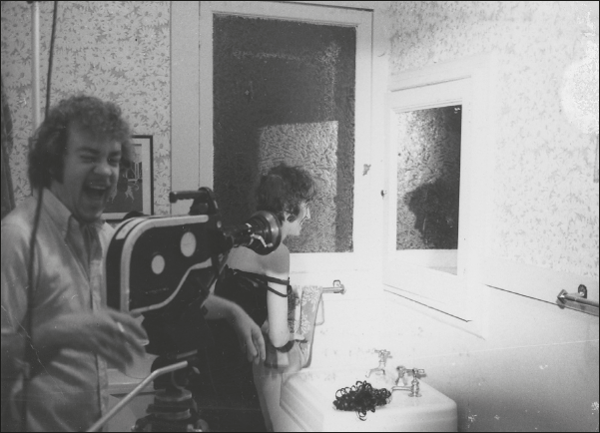

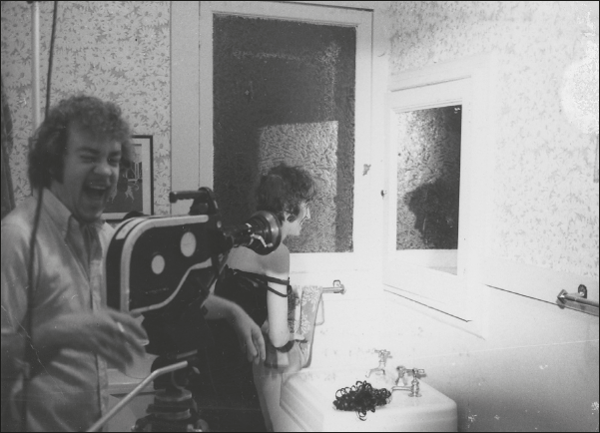

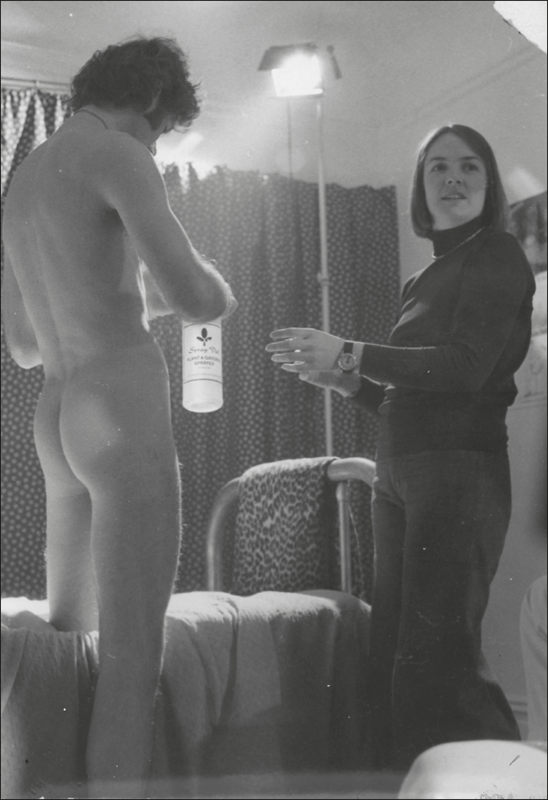

FIGURE 13.1 Thundercrack!(ing) cult cinema: McDowell creating the controversial classic

In the night which follows, all of the guests change clothes in what the script calls the ‘lewd bedroom’, the room which had belonged to Gert’s son Gerald, who ‘no longer exists’. While they change (and play with the many sex toys which litter the room, along with walls covered with porn), Gert watches them from a peephole and masturbates with a peeled cucumber. Sash and Chandler go down to the basement to get a bottle of wine for dinner and act out a cross-dressed male hustler scenario set in a bus depot which ends with Chandler making love with Sash nude in the missionary position and achieving orgasm all over her to their shared delight. Toydy comes on to Gert in the kitchen and is ready to sodomise her using bacon grease as lube when his cruel insults send her into a rage and she nearly castrates him with a meat cleaver. The virile Bond easily seduces the naïve Wilene, and the two fall in love. Soon afterward, Toydy takes Bond aside and offers to exchange his hidden crate of bananas for Bond’s ass.

As the story progresses, each character reveals a hidden trauma or shameful secret. Gert’s husband had been devoured by locusts and is pickled in a jar in the basement. Chandler’s wife, lingerie heiress Sarah Lou Phillips, had died when her girdle caught fire, and the trauma has left him impotent. Finally, the deranged circus driver Bing arrives after crashing his animal truck in a suicide attempt. He reveals that he is hopelessly in love with the female circus gorilla Medusa and that the two are sexually involved. The escaped gorilla is crazed with lust and rage. And Gerald is not dead, but hidden behind a locked door, an insatiable monster with enormous distended testicles which hang to the floor. Medusa breaks through the front door, and Bing leads her to the back bedroom, dressed in Gert’s wedding dress, while everyone makes their escape. When Roo and Toydy open the locked door hoping to find a family fortune, a hideously disfigured Gerald staggers out of the darkness, and Gert pushes the two interlopers into Gerald’s cell and locks the door. The movie’s dénouement signals a deeply ironic ‘return to normality’ featuring three heterosexual couples. Bond and Wilene drive off together, Chandler and Sash turn their car away from Waco, Texas and Chandler’s plan of setting fire to the girdle factory, and Gert opens the jar containing Charlie’s remains, pours a glass of whisky into it, and invites him to join her in a toast.

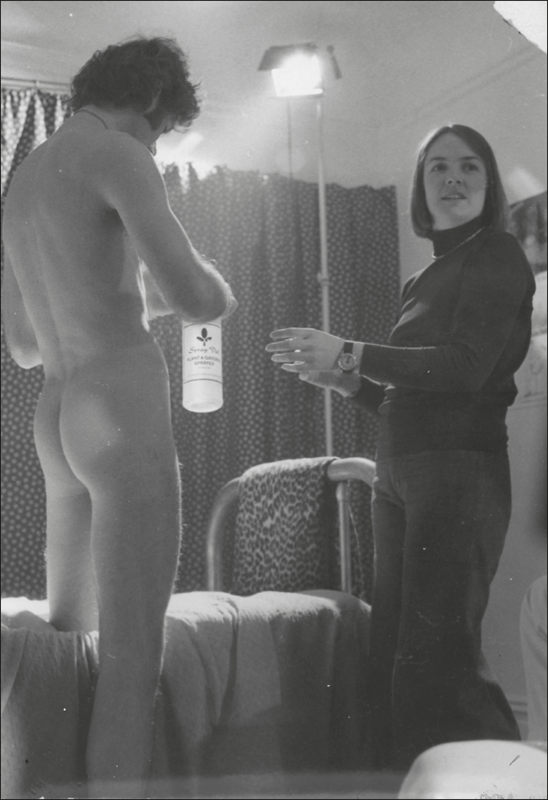

FIGURE 13.2 Cast and crew discuss sexually subversive strategies on the set of Thundercrack!

FUNDING FLESH: THE PRODUCTION CONTEXTS OF THUNDERCRACK!

Who could McDowell and Kuchar persuade to invest in such an idea? How about the same people who devised the fast-food ‘value combo’ of flame-broiled hamburger, fries and a coke for 40 cents in Indiana in the 1950s? San Francisco residents John and Charles Thomas were sons of Burger Chef chain founder Frank Thomas, who had sold the company to General Foods in 1969, placing the young Thomas brothers in a position to serve as patrons of the arts. Furthermore, tax shelter laws in 1974 enabled investors to put up as little as 25% of a film’s budget in cash and take an investment credit on the full 100% of that movie’s total cost. This enabled an investor in a modest feature film to wipe out taxes on tens, perhaps hundreds of thousands of dollars of non-movie income.

The Thomas brothers, present on the fringes of the San Francisco bohemian community, knew Curt McDowell through mutual friends at the Art Institute and were excited to invest in an iconoclastic underground horror-comedy-porno film and to use the commercial potential of distributing such a film under the banner of their newly-formed Thomas Brothers Studio as a springboard for other projects. In 1975, John and Charles Thomas put up $4,500 apiece for 50% ownership of Thundercrack Ltd., a California limited partnership of which they each owned 25%. The other 25% interests were owned by Kuchar and McDowell.8 Then, in late September, two of the most crucial pieces of the Thundercrack! puzzle fell into place: Curt went on unemployment, and Melinda permanently moved to San Francisco from Indiana.

The relationship between Curt McDowell and his sister Melinda is one of the most distinctive artistic collaborations in all of independent cinema. Since his earliest creative expressions drawing cartoons and writing songs, his baby sister had been his constant muse and closest confidante. It was Melinda to whom a tearful-eyed Curt came out as ‘queer’ at age 16 when Melinda was nine years old, and Curt’s scrapbooks are full of photographs he took of Melinda looking up from children’s books, standing in Yosemite with flowers in her hair, or glowing in high-contrast black and white photographs emphasising her wide, round eyes. To Curt, this idealised and protective view of his little sister Melinda was reinforced rather than compromised by his celebration of her adult sexuality in both his films and their adventures together in the clubs and bath houses of San Francisco. It was in the person of his beloved sister that the two worlds of Curt McDowell, the security of his Indiana home and the sexual freedom of San Francisco, found their deeply longed-for unity.

With George’s Thundercrack! script in hand, Curt and assistant director Margo O’Connor began scouting locations, scouring the city for props and casting the film. The role of the gentle and childlike Sash immediately went to Melinda. The professional porn actor Ken Scudder, who was dating Melinda at the time, auditioned for the role of Toydy, but that role eventually went to a local portrait artist, Rick Johnson, who Curt was excited to find was ‘a true bisexual’ and capable of performing passionately and uninhibitedly with both male and female cast members. Ken was then assigned the role of the rough-trade hitchhiker Bond, and Maggie Pyle won the role of the initially-naïve Wilene. The foul-mouthed and constantly scowling Roo was played by local actress Moira Benson, and George Kuchar (who applied the actresses’ makeup up under the nom d’ecran ‘Mr. Dominic’), agreed to play the role of the demented circus driver Bing. Curt himself played the sexual monster Gerald, the source of his mother’s shame and possessed of insatiable appetite and balls which hang to the floor.

Another young actor answering the casting call was Phil Heffernan, who had just finished producing a 16mm character-driven porn feature entitled Sip the Wine (Dan Caldwell, 1976). His audition and screen test landed him the role of the conflicted and neurotic Chandler (he was billed in the film’s credits as ‘Mookie Blodgett’, originally a screen name devised by Curt and George for Moira Benson). Heffernan’s other contribution to Thundercrack! was bringing the casting call to the attention of his leading lady in Sip the Wine, Marion Eaton, who read for the role of Mrs. Gert Hammond. Before performing in Sip the Wine, the 45-year-old Eaton was an actress with a long list of roles in community theatre and independent drama productions including Desdemona in Othello and, importantly for her role as Gert, Maggie in Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.

Although no fan of conventional porn films, Eaton was outspoken in her defence of on-camera sex as a legitimate part of the actor’s craft, likening scenes of explicit sexuality to ‘emotional arias’ which can grow out of an actor’s embodiment of the character.9 In Marion Eaton, Curt had found an actress able to anchor the film’s wildly divergent narrative lines and emotional registers with a performance wholly consonant with prevailing norms of virtuosity and professionalism. Gert’s fragile façade of gentility set gingerly atop a boiling cauldron of loneliness and rage both elicits genuine audience sympathy and sets the movie in the tradition of ‘menopausal horror’ exemplified by What Ever Happened to Baby Jane (Robert Aldrich, 1962) and Hush… Hush Sweet Charlotte (Robert Aldrich, 1964). In short, the casting of Marion Eaton in Thundercrack! would be McDowell’s big score. The movie would ultimately belong to her.

FIGURE 13.3 Eaton’s ecstasy: Marion on the set of Thundercrack! with George Kuchar and Curt McDowell

SHOOTING SEX: THE CULT SKIN FLICK TAKES SHAPE

Shooting for Thundercrack! began in early March in Charles Thomas’s house, which doubled for the Prairie Blossom farmhouse. The first scenes McDowell shot were the crucial explicit sex scenes which punctuate the story: on the first day, Melinda and Phil enacted Sash’s basement seduction of Chandler. For the remainder of the week, the cast and crew worked on the explicit scenes, including the ‘lewd bedroom’ scenes of masturbation, Bond’s hallway encounter with Roo, and Bond’s deflowering of Wilene. The following week, Curt shot most of the living room scenes and the volcanic sex scene between Toydy and Bond with Chandler seated at bedside.10 A major asset to the production was the speed, style and efficiency of Kuchar’s lighting design and execution. The living room scenes feature bold, expressionist striated patterns of light, and the high-key lighting of the sex between Bond and Toydy emphasises the finely-toned muscles on the actors’ bodies and the glistening and dripping sweat which convey the heat and passion of Bond’s first receptive anal experience.

By the end of the second week, the shoot was picking up speed, and the actors, particularly Marion, were nailing their lines and hitting their marks on the first take. One exception was Maggie Pyle, who was showing up drunk to the shoot every day, blowing her lines, and spending her down time passed out in an upstairs bedroom ‘just like Hollywood’, an angry McDowell notes in his diary.11 Fed up with her unprofessionalism, Curt and Marion exacted revenge: ‘Returned to do the Wilene eats the cucumber scene,’ he notes on March 14. ‘I laughed so hard I actually wasn’t looking through the camera. Wilene, unknowingly, ate the very cucumber Gert had up her coozie two days ago. Everyone kept a straight face but me.’12

For the next six months, McDowell worked on post-production. A rough cut was ready by May,13 and filming of the flashbacks began in July.14 In August, George consented ‘to show his pecker in the flashback,’15 and the following week, Margo O’Connor set aside the gorilla costume (she had played Medusa in many scenes under the name ‘Pamela Primate’) so Curt could don the fur, turn the camera over to Mark, and ‘shoot a scene that ought to go down in history: George (as “Bing”) being masturbated to climax by the Gorilla! (an all-time first!)’.16 Ellinger provided the needed music cues as the final cut took shape, and Curt sent the elements to Leo Diners film lab to make the answer print just in time for George, Curt and Melinda to take a happy Christmas vacation to Indiana.

The film that emerged from Leo Diners in the last days of 1975 contains almost every imaginable element of sensational spectacle while self-consciously subverting any coherent framework needed for these elements to appeal to either a genre audience or the various sub-cultures which constituted the mid-1970s audience for the cult film. The first twenty minutes of the movie is a high-camp parody of the ‘old dark house’ horror thriller, complete with a thunderstorm, a diverse group of stranded travellers, and an isolated house hiding a shameful family secret. The Old Dark House (1932), directed by James Whale and featuring Boris Karloff and a colourful gallery of Hollywood’s closeted (and not so closeted) gay, lesbian and bisexual character actors, provides the most obvious source, complete with its bolted inner sanctum containing the insane and pyromaniacal Saul Femm, the progenitor of Thundercrack!’s Gerald Hammond. The assembled travellers bare their neuroses, some coming to horrible ends, until the family evil is vanquished and the new heterosexual couple of Roger Penderel (Melvyn Douglas) and Margaret Waverton (Gloria Stuart) leave the following sun-drenched morning, signalling the movie’s return to ‘normality’. Thundercrack! extends its parallels to The Old Dark House in the retribution meted out to Toydy and Roo, who use their sexuality to manipulate others and gain money, power or access to the hidden secrets of Prairie Blossom and are punished by their perpetual imprisonment with the deformed and insatiable Gerald.

And then there’s the porn. The use of explicit sex in Thundercrack! is suffused with McDowell’s characteristic combination of knowing irony and rapt erotic fascination. First, the porn elements in the movie are constantly colliding head-on with the basic opposition between the Normal and the Monstrous which is at the heart of the classical horror film. In films such as Dracula (Tod Browning, 1931), Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (Rouben Mamoulian, 1932) and The Old Dark House, monsters are the figures which threaten the stable, safe world of monogamous heterosexual desire. It is the eruption of a transgressive sexuality, usually an inverted mirror image of the world of white Christian monogamous heterosexuality, which is at the heart of the classical horror film’s phobic imaginings, and it is the defeat of the monster and the return to a heteronormative sexual economy which resolves the film’s narrative. Porn, on the other hand, imagines the normal world as oppressive, exhausting, and numbing, and the release of the characters into an experimental ‘pornotopia’ of abundance, energy and pleasure enables them, in the classical 1970s phase of the porn narrative anyway, to return to the normal world transformed and regenerated.17

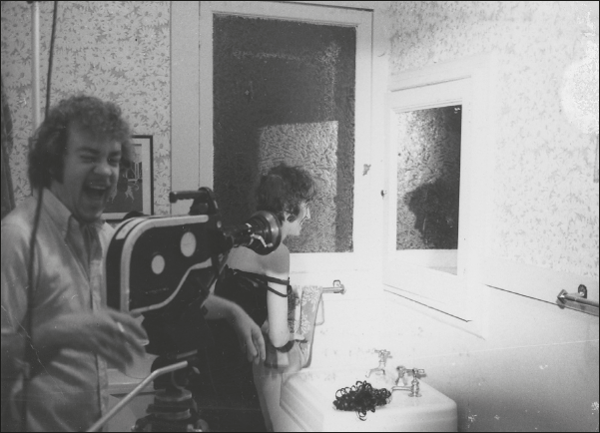

FIGURE 13.4 Porno productions: Melinda McDowell and Ken Sudder rehearse on the set

But it is not merely in the deep structures of the horror and porn genres that Thundercrack! exhibits its delirious incoherence. The movie’s classical horror elements are also its most deliberately anachronistic, from the black-and-white cinematography to the special effects, musical score and dialogue. It is difficult to reconcile the swaying twigs standing in for trees in a thunderstorm, the milk poured into an aquarium to signal roiling clouds, and swarms of murderous locusts played by coffee beans thrown onto the actors with the obviously unfaked close-ups of bodies and organs grinding together, eventually displaying their unruly physicality as sweat, saliva, semen and K-Y jelly glisten under George Kuchar’s Colortran lights. Also, Mark Ellinger’s musical score studiously avoids the ‘wakka chikka wakka chikka’ pelvic rhythms of most (library) porn scores and instead substitutes horror film cues and other jarring themes to the scenes of sexual union. Some of the masturbation scenes in the lewd bedroom are scored to a sprightly boogie woogie theme, changing to a waltz with each cut-in to the voyeuristic Gert. Roo’s masturbation with the enormous dildo is scored to a fairground calliope waltz, and Sash’s appearance in the lewd bedroom (she does not play with the sex toys, but instead makes childlike faces at a wooden handpuppet while making it dance) and her sex scene with Chandler are scored with a lyrical love theme so melodic that the first time Mark played it for Curt in post-production, he ‘almost cried, it was so beautiful’.18 The only scene in Thundercrack! scored in traditional ‘porn’ style is the topping of Bond by Toydy, which is accompanied by pounding drums and searing guitar licks.

But it is in its dialogue that Thundercrack! most humorously (and subversively) undercuts the aesthetic norms of the porn genre. Film pornography’s florid erolalia, or sex talk, is one of its most immediately recognised and frequently parodied features. Thundercrack!, on the other hand, extends the Production Code-era indirect and metaphorical descriptions of sexuality characteristic of the classical horror film into the explicit scenes and allows the characters to declaim long speeches while engaged in every imaginable sexual act.

Although the sex dialogue in Thundercrack! makes use of many hilarious metaphors, it is in the obsession with food that Kuchar’s screenplay provides its most sustained and hilarious parody of Production Code discretion in the discussion of sexual matters. The mostly-consumed remains of Charlie Hammond, pickled in a jar, find their correlative in the unpickled cucumbers with which Gert relieves her loneliness. The frustrated Gert is paralleled by the rage-filled Medusa, who craves similarly phallic-shaped bananas to assuage her angry guts. At times, the Production Code seems to have taken a detour through a seventh-grade boys’ locker room. In the lewd bedroom, Toydy grabs Sash’s breasts from behind while announcing, ‘I heard this was melon season, and now I believe it,’ and he later bends Gert over the kitchen counter to sodomise her because she reminds him of ‘something Greek, like a nice piece of shish kebab meat’. Roo’s later hallway fellating of Bond is described in terms of frankfurters, mustard and ketchup, and, getting Toydy in the identical situation, she sneeringly demands his ‘cream gravy’ to go on her ‘boiled tongue’ and ‘baked potatoes … with the jackets on ‘em.’ Pangs of hunger, shudders of fear and spasms of pleasure are locked in a titanic struggle for 150 minutes. Thundercrack! careens so wildly between these different registers of ecstasy that the ultimate audience reaction is another bodily convulsion; raucous laughter. Kuchar’s tongue-in-cheek allusion to the bodily immediacy of genre cinema in the movie’s trailer could very well state the irreducible nature of Thundercrack!’s appeal as horror, porn, melodrama and comedy: ‘If you ache beneath your intestines, or scream silently in the cavities of your chest, then this picture is for you!’

ROGUE RECEPTIONS

So who was this picture for? On 29 December, the film had its world premiere at Anthology Film Archives in New York. Anthology, conceived, built and run by Lithuanian-born Jonas Mekas, tireless connoisseur, promoter and impresario of experimental cinema, was the ideal venue for introducing the movie to the New York experimental film community, of which George Kuchar was an emeritus member. McDowell notes in his diary that ‘It was sold out even though it wasn’t advertised… The film looked great to me and went over so well, that I was ecstatic (all sorts of stick-in-the-muds who normally would walk out stayed for the whole thing).’19 Then, in January, Charles Thomas screened the movie for Mel Novikoff, an important San Francisco exhibitor and film festival organiser whose West Coast Surf Theater Chain would later form the basis for the national Landmark circuit of art theatres. Unlike New York’s Ben Barenholz, who had responded favourably to Waters’ Pink Flamingos and booked it into his Elgin Theater for weekly midnight screenings and allowed it to slowly build a reputation, Novikoff walked out of the screening of Thundercrack! before it even got warmed up with its lewd bedroom scenes.20

Later that month, the Thundercrack Ltd partners were delighted to learn that the movie had been accepted at FILMEX. Not only would this be a prestigious high-profile event, it could also lead to a distribution deal if the screening went well, much as later independent filmmakers hoped that acceptance into Sundance would bring their movies into contact with willing distributors. According to Kuchar, the pre-screening committee at FILMEX had wanted to reject the movie out of hand before they had even watchedit. But one of the jurors, screenwriter and actor Buck Henry, told them that without Thundercrack! on the 1976 FILMEX programme, he would not participate in the event.21 McDowell’s diary reports that

the show was like a dream, and the response was so overwhelming that I couldn’t have asked for more… At the end, [festival hosts] invited me to get up and talk, and I felt the orgasm of applause… I was thrilled to death that Marion received a standing ovation (I know she was ecstatic).22

Unfortunately, McDowell did not leave FILMEX with any offers to distribute the film, but Thundercrack! did receive its first round of critical notices soon after its FILMEX premiere.

The reviewer for Daily Variety lambasted the movie’s ‘poor sound quality, amateurish acting, and interminable gab between the sex scenes [which] make the 150-minute running time an ordeal’ and noted that ‘Curt McDowell takes blame for direction, lensing, and editing’ but praised Kuchar’s lighting and Ellinger’s score.23 Other reviewers found the movie’s pansexual subtext fascinating, troubling or both. Todd McCarthy, writing for The Hollywood Reporter, noted that ‘masturbation and heterosexuality dominate up to a certain point, until finally the homosexual streak running through the picture resolves itself in a genuinely effective gay hard-core scene which is carefully photographed and effectively scored’.24 Over a year later, Joseph Michaels, writing in The Advocate, would opine, ‘gay this film ain’t, and hardly erotic … by the end of the film, all the characters have realigned themselves into male/female couples’; for Michaels, the hetero porn elements cancelled out the horror motifs, making the movie’s ironic ending a cop-out rather than a send-up.25 Just a couple of months before Michaels’ review appeared in The Advocate, Curt used that magazine’s pages to note with some irritation:

As far as the gay culture’s attitude towards me: I think they’re confused. They like my humor and vision of men, but they only like my women if they’re all made up and caricatures… But I hate classes and categories, except as interesting subjects for film. It’s far too limiting to latch onto a single group and dedicate yourself to a community that might as well as have walls around it. How can you possibly grow if you do that.26

Attempting to book Thundercrack! into commercial hard-core theatres was a fool’s errand. With a black-and-white movie which dispenses of its sex scenes with maximum efficiency in order to get to its next long character monologue, which is too gay to be straight porn and too hetero to be gay porn, Thundercrack!’s only market niche appeared to be the midnight cult circuit which had been so kind to John Waters’ Pink Flamingos and Female Trouble (1974). But here the movie’s length hamstrung exhibitors: even a stoned youthful audience of urban ne’-er-do-wells would face exhaustion at the end of a 150-minute movie, and that’s not counting trailers for coming attractions and the inevitable cartoon. Still, stimulated by the notoriety of its Anthology and FILMEX coastal premieres and buoyed by its success at the Seattle Film Festival, a positive review in Sight and Sound, and a run at San Francisco’s Roxie Cinema, Thundercrack! brought in $5,000 in rentals in 1976.27 The word-of-mouth increase in interest which had accrued to Pink Flamingos never attached itself to Thundercrack!, however. The following year only brought $3,200 in rentals for the film.28

Since Thundercrack’s two-and-a-half-hour running time was becoming a liability in securing midnight bookings for the film, the situation which all agreed was ideal to allow word of the movie to spread to an audience; in early 1977 Curt prepared a shorter 110-minute version to submit to New Line Cinema. John Thomas had written to McDowell six weeks earlier stating that Waters had told the Thomas Brothers that ‘New Line was really the only company and/or the best company to handle’ the movie and that he had been treated fairly and paid well by New Line.29 But the 70/30 deal proposed by New Line in 1978 never came to pass, and dealings between Curt and John and Charles became increasingly strained. Even before the New Line deal soured, George Kuchar became disillusioned with the in-fighting between the general partners and the artistic compromises represented by the shortened version of the movie and withdrew himself from the partnership, seemingly on the eve of a potentially lucrative deal with New Line. In a letter to Curt’s legal advisor Robert Brandes, Kuchar asks that publicity and advertising for the film list him only as an actor in the film ‘since the picture makes less sense that it originally did [and] I don’t want the fact that I wrote it played up big in their advertising’.30

Since the partnership had withdrawn the film from circulation for much of 1978 in anticipation of the New Line deal, that year’s film rentals amounted to a paltry $800.31 By 1980, McDowell had enlisted the services of veteran film booker Anita Monga to distribute the short version of Thundercrack! under the rubric of Taboo Films, but this was largely a shell company to hide the fact that Curt was essentially self-distributing the film with Monga serving as booking agent. The one-off Taboo engagements of the movie over the next two years would bear a greater resemblance to the non-theatrical bookings of Curt’s short films through Canyon Cinema Cooperative than to the commercial distribution of a feature film.

THUNDERCRACK! AND BEYOND

The devolution of Thundercrack’s commercial prospects, depressing enough in itself, was particularly painful to McDowell since the entire enterprise had been conceived to make money to finance more personal projects. Shortly after completing editing on Thundercrack!, Curt began a project which would eventually be his ultimate love letter to Melinda, Sparkle’s Tavern (1985),32 but in early 1976, John Thomas told Curt that the money for the new project was not forthcoming.33 The reason for this would become apparent later in the year, when revisions to the Internal Revenue Code limited tax deductions to motion picture investors to the amount at risk.34 Despite these setbacks, McDowell shot Sparkle’s Tavern throughout late 1976, deferring huge parts of the budget to keep the project going. McDowell was indefatigable in his efforts to secure completion financing for the project, applying for an American Film Institute Independent Filmmaker Program grant in 1978 as well as a National Endowment for the Arts grant to finance the post-production and release prints of Sparkle’s Tavern, but his applications were denied. It was not until late 1984 that Curt would finish post-production on Sparkle’s Tavern courtesy of a loan of more than $10,000 from Marion Eaton and her spouse Bill Feeney. Curt was diagnosed with AIDS just two years later, and he passed away the following year, on 3 June 1987.

In one of the bitterest ironies in this tale of McDowell’s cursed and brilliant film, Curt died at precisely the moment that many eccentric filmmakers found an entirely new source of financing and distribution for their work in the expanding market of home video. Companies such as Island Records, Vestron Video and RCA Columbia Home Entertainment began to finance first dozens, then hundreds of feature films, and holy fools of filmmaking silent for years such as Ken Russell, Nicholas Roeg and John Waters found themselves back in the director’s chair with multi-picture deals. Also, a New Queer Cinema emerged as home video cultivated profitable niche markets with carefully calculated production budgets and videocassette price points. Filmmakers such as Todd Haynes, Gus Van Sant, Greg Araki and Rose Troche used the money from video presales to finance a queer cinema in a queer voice. Canada’s Bruce La Bruce, whose highly idiosyncratic films such as No Skin Off My Ass (1991) and Super 8½ (1993) integrated hard-core sex scenes with trenchant observations on the foibles of queer culture, followed in the footsteps of McDowell. These and other descendants of Curt McDowell would soldier on in the absence of their advance scout, and every salvo of explicit sexuality they discharged could not help but invite comparison to Thundercrack!, which in the words of the movie’s original FILMEX programme notes, had ‘created a new motion picture genre, a transcendent, meta-porno flick which elevates the viewer to hitherto undreamed of heights of salacious consciousness’.35

Author’s note

Since the financial collapse of the Curt McDowell Foundation in the late 1990s, Melinda McDowell has been the sole custodian of all of Curt’s papers, diaries, films, and financial records. Unless otherwise noted, all of the citations given are taken from Curt McDowell’s diaries and scrapbooks. For this reason, some bibliographic details such as dates and page numbers from long-discontinued local and countercultural newspapers and non-indexed newspapers and trade journals have been impossible to recover.