‘Already a development is beginning in the film world that is exactly like the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia.’

– From the introduction to a 1968 zadankai (round table) discussion featuring the six most prominent film directors of the time, regarding the majors’ entry into ‘Pink’ territory by producing ‘Pink’ lines.1

The above quotes encapsulate the feeling of antagonism towards the major studios that the protagonists of the Pink film industry formulated again and again in the 1960s and early 1970s. The allusion to the suppression of the Prague Spring also speaks of the surplus value consistently attached to the genre: political anti-authoritarianism and the smell of revolution. This sweeping trope of resistance – against the economic authority of the major studios, the political authority of the state, the moral authority of the established media and various public institutions – has been attached to Pink film repeatedly over the decades since it first appeared in the early 1960s and became the biggest cinematic success story of the decade, indeed one of the biggest in the entire history of film in Japan. In the three years from 1962 to 1965, what would later be called Pink film went from non-existence to over 200 films and 44 per cent of total feature film production. And unlike most of the cinemas of sexploitation reviewed in this volume, Pink film is still alive and active, if ailing, producing around seventy 35mm films a year.

Yet how accurate is such a claim of resistance as a generic trait? It has, with slightly different nuances, migrated across various parties over time: the Pink film industry itself in the 1960s, the student movement in the late 1960s, Japanese film critics of the late 1970s and early 1980s, and, more recently, American and European academics and curators involved in the revival of interest in the genre. It is no coincidence that in 2007 Meike Mitsuru’s, Nakano Takao-scripted The Glamorous Life of Sachiko Hanai (Hanai Sachiko no Karei na Shôgai, 2004) became an international festival success and the first Pink film in decades to be released theatrically in the United States. The considerable publicity the film received focused on its absurdist-framed criticism of the Iraq War: the protagonist, a sex worker specialising in role-play, becomes entangled in the international hunt for a replica of George W. Bush’s finger, endowed both with the ability to trigger the apocalypse and a lusty life of its own. In September 2007, the French Federation of Film Critics (SFCC) officially protested the rating of the re-release of Wakamatsu Kôji’s The Embryo Hunts in Secret aka When the Embryo goes Poaching (Taiji ga Mitsuryô suru Toki, 1966) as restricted to audiences below 18 years of age. The aura of Pink resistance politics is not only still glowing even in Europe and the US, it also obviously influences the kinds of films that are selected for release. A similar paradox occurs in Japan, where the histories of Japanese film – such as those by Satô Tadao or Yomota Inuhiko – tend to only slightly touch upon Pink film.2 When they do, however, they focus on the exception to the exclusion of virtually all else. Wakamatsu Kôji, the first (though by far not the only) brand name in Pink film, and, in the 1960s, the Pink director and producer most prone to explicit political expression and formal experimentation, becomes a pars pro toto of the entire genre. This kind of strategic spotlighting simultaneously hides a vast part of the genre from view while enabling a kind of legitimatisation of a disreputable section of cinema history.

PINK FANTASIES

The marginal role of Pink film in the US, and increasingly in Japan, may further support this tendency, enabling reflexes of projection and nostalgia. In its formative period, however, Pink film was anything but marginal. In 1962, three of what would later be defined as Pink films were released in Japan. In 1963, 24, in 1964, 65, and by 1965, an astounding 213 Pink films were released, a number that would decline only slightly for many years (although the definition of a Pink film is usually vague enough to allow for slight variations in numbers, depending on who’s counting). How involved in actual ‘resistance’ can a genre as a whole be, when it at one (later) point provides more than half of the entire feature film output? Pink film certainly participated in complex social, political, aesthetic, even literary discourses. This essay will not dispute the discursive space that Pink film opened for film practitioners and audiences, nor their potential for strategic political interventions. It will, however, focus on the mechanisms of collaboration that made the opening of such discursive spaces possible in the first place. It will trace the specific historical circumstances of an industrial pragmatism that was not at all anathema to the narrative of resistance, even on the side of the major studios. And it will examine how Pink film influenced the restructuring of the Japanese film industry to enable its very survival, initially playing the role of an economic and political avant-garde but soon becoming a time-lagged storage room of traditions.

There is no question that Pink film latched onto a number of discourses that were of considerable significance and heightened salience especially in the 1960s. The Pink film industry stood for a return to independent production and, more importantly, distribution after a decade of near total major studio monopoly. Independent production was still heavily associated with the concretely leftist positions of the by-then extinct independents of the early 1950s, which were often linked to unions or political organisations. The emphasis on the body was connected to immediate post-war discourses as formulated by the ‘literature of the flesh’, which used the body as a starting point for re-establishing a sense of personal subjectivity. The opposition towards official definitions of obscenity were part of the larger package of discontents with a state that was perceived as authoritarian and under Western influence. On-location realism in aesthetics and storylines clashed with the stylishness of the major studios. Class was being problematised in the relationship of the small independent sexploiters and the majors, spanning from the ideas about Pink film audiences and the directors’ pedigrees: only those with elite educational records could even hope to enter the studios, and Pink directors habitually portrayed themselves as a much more blue-collar lot. All of this of course carried implications for the construction of nation.

The two scandals of 1965 that heaved Pink film into the public limelight in Japan both carried deep national implications: Wakamatsu Kôji’s film Affairs Within Walls (Kabe no Naka no Himegoto, 1965), highly critical of the social order accompanying the boom economy, screened at the Berlin International Film Festival and was dubbed a ‘national disgrace film’ in the press. The highly publicised obscenity trial against Black Snow (Kuroi Yuki, Takechi Tetsuji, 1965) concerned itself with a film that polemically criticised the American military presence in Japan. In the late 1960s the student movement was quick to pick up on these undercurrents, and Pink films played regularly at university gatherings. Adachi Masao, one of the most experimental, intellectual and political figures from the Pink film industry eventually left Japan to join the Japanese Red Army in Lebanon. All of this played into the larger image of Pink film as a genre, and all of this contributed to the considerable power of attraction it held for a certain period of time.

FIGURE 15.1 Desire under the eye of a dictator: Wakamatsu Kôji’s scandalous Affairs Within Walls

Yet unsurprisingly the point of departure for what was to be called Pink film was economic reasoning, the unfailing ability of sexually-charged films to attract an audience. While the idea of Pink film as resistance was real (at least for certain groups at certain times), the question remains how structurally founded it was. At the root of Pink film’s identity lie the supposed dichotomy of Pink film and the major studios, and it merits closer inspection. At the beginning of the 1960s the six Japanese studios Daiei, Tôhô, Shôchiku, Shintôhô, Tôei and Nikkatsu were all in dire straits. The booming economy brought on not only by television but by a whole host of new and newly affordable leisure activities, all in direct competition to the film industry. The majors devised several coping strategies, one of which was the focus on specific segments of the general audience. Eventually, all but Tôhô proceeded to focus increasingly on the preferences of the male spectator, abandoning the female audience to foreign films and the new medium of television. Yakuza films, action films and increasingly explicit sexual content soon dominated the screens. Pink film was, at this time, often portrayed as a threat to the majors’ hegemony and very survival, an unwanted invader in an already troubled market. This characterisation of Pink film was summed up in typical headlines such as ‘The 3 Million Yen Films that are Threatening the 5 (Major) Companies’ or ‘To What Degree are They Eating the Majors’ Market?’3 However, this is not the whole truth. In fact, several of the majors’ strategies not only created a virtually ideal environment for the meteoric rise of Pink film, they even relied heavily on Pink film to sustain the exhibition industry. At some point every single one of the majors inserted Pink films into their programmes and theatres, and most even dabbled in Pink film production, though often surreptitiously, something we will touch upon later.

From 1959 on, the financially imperilled studios starkly reduced production and resorted to ‘setting free’ the creative and technical staff, previously strictly bound by studio-exclusive contracts, and at the same time curtailed their production activities. The resultant reduction in films created immense problems especially for the second- and third-tier theatres which depended almost solely on studio production to fill their weekly changing double- and triple-bills. In 1956/57, the distribution income of independently-produced feature films comprised a miniscule 0.34 per cent of the total gross, so initially there simply was no alternative. Yet because audience turnout declined rapidly after the first week of screening, weekly programme changes were an absolute necessity. Pink films closed this cinematic gap perfectly. Low production budgets of under 3 million Yen (a little more than $8,000 in 1965) and a legion of now underemployed film industry workers provided an ideal environment for Pink film production. Takahashi Eiichi calculated the following statistics in 1968: in 1958 the major studios released 503 films; by 1965, this number was down to 277, which was supplemented by 225 Pink films (by his count) – which amounts to the previous total of 503 films.4

Pink production was highly flexible, and in comparison to the studio system a vanguard of liberalised labour relations. The director simultaneously functioned as the producer, setting up a pro forma production company; upon making a deal with a distributor about the script, he would receive a part of the budget for actual production, and the rest for the completed film. This provided the director with a significant amount of influence over the finished product, and often the distributors didn’t care about the aesthetic or political specifics as long as the required amount of ‘sexiness’ was supplied. Staff was assembled for each separate production, not continually employed. The studios’ new policies left some highly-skilled practitioners out of work, and they found ready (and often anonymous) employment in the Pink film industry: for his 1965 debut feature Hussy (Abazure), the young Watanabe Mamoru was able to use a cameraman that had worked with Mizoguchi Kenji and a lighting chief that had worked for Kurosawa Akira. Motogi Sôjirô, a prominent Pink film director, had originally worked as a producer for Tôhô, producing among others Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950) and The Seven Samurai (Shichinin no Samurai, 1954).

However, Pink films were embraced by exhibitors for more reasons than simply stuffing the gaping hole the studios had left. They attracted audiences with a welcome predictability, and the distributors charged much lower fees for the films than the majors did. By 1965 over seventy small companies were involved in the production of Pink film, and they either self-distributed their films or sold them to the regional distributors that were popping up by the dozen. The pressure of overproduction and inexperience in distribution quickly led to dumping prices for Pink films. At the most, exhibitors were charged 20 per cent of the box office for Pink film screenings, while major productions commanded 50 per cent. And, at least in the early phase of Pink film, audience turnout was often better than that achieved by studio films.

As so few Pink films from this period survive or are available for viewing, it is difficult to explore their aesthetics and narratives. In terms of storylines, the mid-1960s were far less standardised than the genre would eventually become. One of the pioneering successes was the female Tarzan film The Valley of Desire (Jôyoku no Tanima, 1962) by, appropriately, animal documentary specialist and later prominent Pink film director Seki Kôji. Another was Lara of the Wild (Yasei no Rârâ, 1962) by strip-show owner Kitasato Toshio, advertised as the story of a ‘vampire fly from the Soviet Union [that] provided a woman with an ecstatic death while sucking her blood’.5 A very large portion of the films feature storylines about the fate of innocent girls violated by malevolent men, but also stories about honeymoons gone bad, action films, period films and even Pink ghost films (pinku kaidan) such as Ogawa Kinya’s Supernatural Tale [of the] Dismembered Ghost (Kaidan Bara Bara Yûrei, 1968).

Pink film has always been characterised by an uneven spread of ambition: some directors attempt to make the most of the low budgets and the often astonishing freedom for narrative and formal experimentation, while others simply go through the motions. However, themes and stories would generally become much more formulaic and immediately sex-centred in the early 1970s, with subgenres such as the mibôjin (widow) films, danchi dzuma (suburban wife) films, joyû (woman’s bath house) films, or the infamous chikan densha (train molester) films. This standardisation is rooted in several factors, but two seem most important: the attempts by powerbroker Ôkura Mitsugi to craft a Pink film industry on the model of the studio system, and the major studios’ increased involvement in and encroachment on the Pink film industry.

Ôkura Mitsugi has variously been stylised as a visionary businessman, a box-office record breaking producer, a pusher of ero-guro (erotic-grotesque) films, an egomaniacal one-man show and the father of Pink films. The legends woven around him have as much to do with his flamboyant and provocative self-promotion as with his radical business methods. Ôkura first gained a hold in the film business as a katsuben or benshi, the narrators who accompanied silent film (and, for a short time, sound film) with their explanations and theatrics. Ôkura was very popular in this line of work and accumulated some wealth, eventually entering the film exhibition business by building a chain of 36 theatres. On 29 December 1955, Ôkura entered a more public position by becoming head of the smallest of the major studios, Shintôhô. Ôkura immediately restructured the company, cutting budgets and shooting days, limiting the maximum length of a film, and exchanging veterans for younger, less experienced (i.e. cheaper) and supposedly fresher staff. This included directors, actors, cameramen and set designers, and was a radical move in a working environment dominated by the traditional seniority system. He also reasoned that stars were expensive, and that it was better to rely on genres to sell a film, a stance he would later take with regard to Pink films as well. With his assumed expertise gained from his experience of exhibition, he adjusted the company’s genre palette to the low-brow audience of the second- and third-run theatres that Shintôhô had by now ended up supplying. Ôkura strategically split up production between big-budget extravaganzas and much cheaper genre fare. On the lower-budget end of the spectrum was The Revenge of the Pearl Diving Queen (Onna Shinju Ô no Fukushû, Shimura Toshio, 1956), with Maeda Michiko as a scantily-clad pearl diver (or ama in Japanese). The very successful film featured the first nude scene in a film from Japan, although all audiences saw was a very short glance of a backside. As a grand spectacle he produced the first film featuring the Tennô as a character, Emperor Meiji and the Great Russo-Japanese War (Meiji Tennô to Nichiro Dai Senso, Watanabe Kunio, 1957), which generated fever-pitch publicity and became the most successful Japanese film of all time.

However, towards the end of the 1950s audiences began to drop off, and Shintôhô felt it most severely. Ôkura eventually abandoned the risk of big-budget projects and focused on films spiced heavily (for the time) with horror, violence and eroticism. As the studio’s fortunes declined, so did the patience of his scandalised studio employees. Never a stranger to controversy (when once asked at a press conference if the rumour he had made actress Takakura Miyuki, star of several Shintôhô films, his mistress were true, Ôkura responded that he hadn’t made an actress his mistress, he had made his mistress an actress), he was eventually forced to resign due to an in-house money scandal related to the sale of the studio lot. In consequence, Ôkura initially focused on his exhibition chain, showing a mix of second-run films from Japan and imported films, among them so-called shô eiga (show films, usually fake documentaries of strip shows) and Roger Corman films. He also re-entered production with another 70mm spectacle and several smaller films, but the results were disappointing apart from one low-budget film called Flesh Market (Nikutai no Ichiba, Kobayashi Satoru, 1962), that would later be called the very first Pink film. The film was based on a serial in the magazine Bessatsu Naigai Jitsuwa which in turn was based on an incident that supposedly actually occurred in October 1961 in the Roppongi section of Tokyo, at the time a central hangout for American GIs and seen as a hothouse of hedonistic Westernised culture. In the story, Harue and her fiancée Kinoshita visit a club in Roppongi. She is raped in the toilet, and Kinoshita consequently breaks off the engagement. When Harue commits suicide by jumping from the roof of a building, her little sister Tamaki enters the Roppongi club scene to investigate, looking for revenge. The film ran into legal problems when the police confiscated all prints on suspicion of dissemination of obscenity, despite having been passed by the Administration Commision for the Motion Picture Code of Ethics (Eirin). The film was released again after several cuts were made, and became a considerable success due to the publicity. Ôkura then refrained from further sex-heavy productions for a while, but his films met with very limited success. Two years later he apparently realised that the proliferating business of low-budget erotic productions promised much wider profit margins than horror films and risky big-budget war films. Ôkura had Ogawa Kinya, an assistant director from his earlier productions that had shot some Pink films for the production company Kokuei in the meantime, shoot the very successful Female Animal, Female Animal, Female Animal (Mesu, mesu, mesu) in 1964, and this was the start of Ôkura’s enduring and exclusive focus on Pink films for the rest of his career and life.

Ôkura went to work immediately, merging with several Pink production/distribution companies and forging the first national distribution and exhibition circuit for Pink films, the OP (Ôkura Pictures) Chain, in 1965. OP was vertically structured, much like the major studios themselves: it possessed theatres, a distribution arm and even a small studio lot. This gave it an immense advantage over the majority of the more improvised Pink production outfits, which often had only two or three employees and a ramshackle office. Ôkura’s dominance eventually forced a trend for consolidation among Pink film companies, a number of which banded together to form the loosely structured Dokuritsu (Independent) Chain, which included Tôkyô Kikaku, Century Eiga, and the still active Kokuei and Shintôhô (the latter being a different company from the major studio of the same name, which had filed for bankruptcy in 1961). OP launched with ten theatres specialising solely in Pink film exhibition and a host of theatres which used Pink films as programme supplements. Although evidence is sketchy, it is probable that these were the first theatres specialising in the exclusive exhibition of Pink films in triple bills, and Ôkura was certainly the first to systematically work on standardising Pink film production, distribution and exhibition. It is Ôkura’s model that Pink film would eventually sink into in the early 1970s. Pink films would standardise to a length of sixty minutes to play in triple bills, their budgets would become basically fixed at around three million Yen, with much less variation than in the 1960s, and distribution was not free but attached to large distribution circuits. Ôkura’s business strategy was heavily influenced by his time as the head of a major studio, and the Fordist model of film production he instituted adhered to the methods of the 1950s. At the same time the studios themselves were already moving out of this business mode, which they regarded as outdated and inefficient. Their trend was towards the casualisation of labour and attracting audiences via sexually and violently charged spectacle, for both of which they borrowed liberally from Pink film. While Ôkura was attempting to build a Pink studio system, the majors were heavily restructuring and trying to shed the vertical organisation that OP was aspiring to.

The majors themselves had been part of the early pioneering for more sex-themes in feature films. Ôkura had prepared some of the way during his time at Shintôhô in the late 1950s. In 1963, seven of the 37 films classified as seijin eiga (adult films) by Eirin were made by the majors, among them Lies (Uso) by Masumura Yasuzô at Daiei, Imamura Shôhei’s Insect Woman (Nippon Konchû–ki) at Nikkatsu and Narusawa Masahige’s Naked Body (Ratai), distributed by Shôchiku. 1964 then saw the majors more than quadruple their adult film output to 31, with Nikkatsu producing Nakahira Kô’s Monday Girl (Getsuyôbi no Yuka) and Suzuki Seijun’s scandal-invoking Gate of Flesh (Nikutai no mon), based on the classic story by Tamura Tajirô of the postwar ‘literature of flesh’, and the first film from Japan to feature full-frontal upper-body nudity. Tôei produced Watanabe Yûsuke’s Two Female Dogs (Nihiki no Mesu-inu) and Evil Woman (Akujo) for their new line of sex films. Shôchiku had experimented with its brand of Shôchiku nouvelle vague films for similar reasons. Now it turned to an outside seijin eiga production, Takechi Tetsuji’s Daydream (Hakujitsumu). Tôhô likewise bought and distributed an independent production, Teshigahara Hiroshi’s Woman in the Dunes (Suna no Onna). The distribution of films the majors had not produced themselves had become virtually extinct in the ‘golden age’ of the late 1950s. However, Tôhô had extensive experience with the efficiency of subcontracting production in the late 1940s, and was now leading the way in reviving a practice that would eventually become the industry standard – and had been the mainstay of Pink film production from the beginning. In 1970 Tôhô took a historic step when it outsourced its recording, art direction, technical and special effects divisions to affiliate companies it established, and the entire production division itself followed in the same year. The other majors followed suit.

Following the Black Snow trial in 1965, the majors cut back on potentially controversial material; in 1966 Shôchiku even pulled out of a distribution deal for the Wakamatsu Kôji film Phone, Please (O-Denwa Chôdai). But by the late 1960s the situation was desperate, and this time the mining of Pink film began in earnest. Nikkatsu began distribution of Pink films in 1968, as well as producing sex-themed films such as The House of Strange Loves (Onna Ukiyo Buro, Ida Motomu, 1968). Tôei was continuing its highly successful erotic lines with films like Genealogy of Tokugawa Women (Tokugawa Onna Keizu, 1968), The Joy of Torture (Tokugawa Onna Keibatsu-shi, 1968) and Hot Spring Massage Geisha (Onsen Anma Geisha, 1968), all helmed by Ishii Teruo, the wunderkind director of lurid material from the original Shintôhô. Much to the chagrin of the Pink film industry, the latter film employed eleven of the biggest star actresses from Pink film. Essentially, Pink film was being used as an experimentation ground, to see what could be repackaged by the majors.

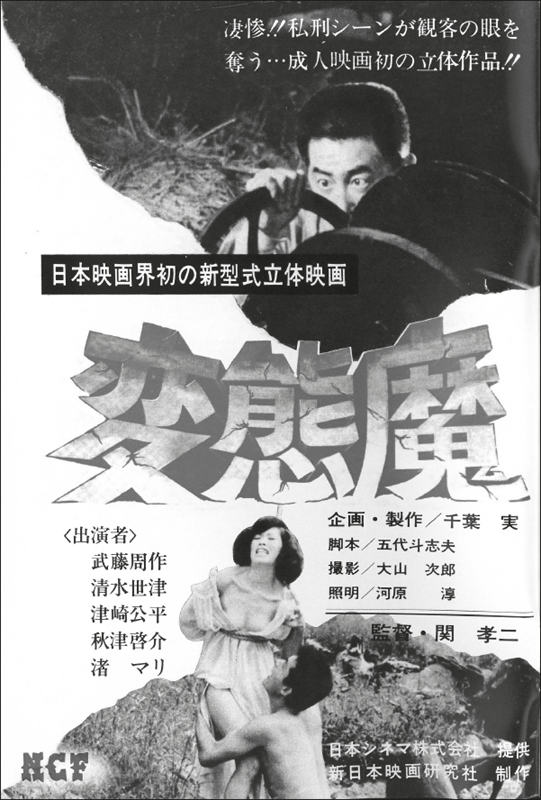

Nihon Shinema had produced the 3D Pink film Pervert Freak (Hentaima, Seki Kôji, 1967), and used Tôei’s developing lab for the complicated technical side. In 1969, Tôei proceeded to release the animated film Red Shadow (Tobidasu bôken eiga-Akakage, Kurata Junji) as Japan’s first 3D film, for which they were forced to apologise. Tôei set up its Pinky Violence line in the early 1970s, transposing the Pink recipe to a genre where Pink budgets were increasingly unable to follow: action films. Nikkatsu stuck closer to the Pink formula when, cornered by extreme financial straits, it switched its entire production to (technically highly accomplished) sexploitation films and created the label Roman Porno. This move from the oldest existing major studio in Japan was a severe shock for the film world at the time, and led to an initial exodus of Nikkatsu employees and stars unwilling to make the transition; consequently, the first stars of Roman Porno such as Shirakawa Kazuko or Tani Naomi were all recruited from Pink film. Likewise, many of the subgenres Nikkatsu embraced had been developed by Pink film: widow films and train molester films became standard fare. Tôei founded Tôei Central Films for the production and distribution of Pink films in 1976, relying heavily on Pink director and producer powerhouse Mukai Kan. Even Shôchiku, the company that was successfully churning out the family-friendly Tora-san series, founded Tôkatsu as a Pink production and distribution outfit. This relied mostly on Pink director Kobayashi Satoru, who by the end of the 1970s was shooting an unbelievable 36 feature films a year for the company. Slyly, the name Tôkatsu is written with Chinese characters that can be found in Tôei and Nikkatsu, but not in Shöchiku.

FIGURE 15.2 Erotic narrative and 3D thrills: Seki Kôji’s Pervert Freak

While all of this may have looked dangerous for Pink film, it ultimately transformed the Pink industry more than it threatened it. Nikkatsu Roman Porno actually brought some stability to the business: Nikkatsu theatres showed triple bills, consisting of two Nikkatsu Roman Porno films and one Pink film. For this, Nikkatsu subcontracted to Pink film companies such as Prima Kikaku or Watanabe Production, which both relied heavily on director Yoyogi Tadashi (who for this reason found himself ensnared in the 1972 obscenity trial against Nikkatsu). In terms of actresses, genres, themes, the aesthetics of rough realism, and even production practice, most of the majors were heavily borrowing from and participating in Pink film; indeed, this partially ensured their further survival. In 1972, an astonishing 196 of the 395 Japanese films released that year were designated as seijin eiga, and the proportion would further rise until the early 1980s.

EROTIC LEGACIES

In response to the major studios’ strategies, the Pink industry, with Ôkura at the helm, increased its drive for consolidation. In 1968 the OP chain assembled eleven of the main Pink production/distribution companies to form a single large distribution network for the Kantô region (Tokyo and surroundings). After only three months, Kokuei, Tôkyô Kôgyô and Nichiei left the agreement, and continued loosely linked but independent distribution. While the OP chain was now geared towards releasing around ten films a month, the three independents together supplied around three films a month. After Roman Porno appeared in 1972, however, the Pink industry was forced to stabilise and standardise even more. The industry settled into the basic structure it would preserve for the next thirty or so years; even the freewheeling Kokuei joined the Shintôhô distribution circuit for good in 1975. While exceptional and ambitious films continued to be produced throughout the genres existence, the idea that Pink film was structurally connected to resistance was rapidly fading. The dichotomy of Pink film and major studios was less and less difficult to uphold in view of the complex web of interdependencies that had developed, and politics, while often still visible, increasingly submerged into abstract storylines or atmospherics. One of the last cases of using Pink film as direct political commentary on current affairs was Yamamoto Shinya’s Molester 365 (Chikan 365, 1972). This film responded to an official warning issued by the metropolitan police that sexploitation films were becoming too daring. Yamamoto’s film features a mysterious case of serial molestation, and the culprit turns out to be a perverted policeman.

Pink film budgets have nominally stayed fixed at around three million Yen since that time, while the value of the money has of course changed considerably. The rise of hard-core pornography available for home video affected the more cinematic Pink film with its simulated sex theatrics much as it did 35mm sexploitation in other countries, but perhaps unusually the Pink film business has managed to hang on until today. In fact, by the 1980s it had become one of the last ports of entry for young directors into a moribund film industry, and today it almost seems difficult to find an established Japanese director that was not at some point connected to Pink film or Roman Porno. The much larger shock for Pink film was the revision of the Law Regarding Businesses Affecting Public Morals in 1984, which put heavy restrictions on posters, themes and film titles. In the latter half of the decade, the majors retreated from the Pink business, and when Nikkatsu pulled out of Roman Porno in 1988, Pink film almost completely came to rely on the specialised Pink exhibition circuit. It is only since the early 1990s that the indomitable Kokuei has attempted to break out of the Pink screening space and tailor its often quite ambitious and experimental films for consumption on video, satellite TV, and in arthouse theatres. It is also Kokuei that has made the biggest mark on international film festivals and markets with the ‘Four Devils of Pink’ (Zeze Takahisa, Satô Hisayasu, Sano Kazuhiro and Satô Toshiki) and the newer generation of the ‘Seven Gods of Luck’, to which the aforementioned Meike Mitsuru belongs.

So where does this leave the overall role of Pink film? Undoubtedly the genre went through various shades of relevance that were often mediated and always historically specific. The mid-1960s presented a time of experimentation and atomised industrial activity. Small companies proliferated wildly and created a great diversity in themes, narrative patterns and styles; this diversity found unity mainly in its common independent production and distribution methods as opposed to the major studios. Pink film’s economically and thematically anarchic character and its affinity to a number of long-standing discourses of anti-authoritarianism supported its explosive rise in a decade of social upheaval and political discontent. The studios in turn found that the very disorganisation and variety of the Pink industry made it an ideal testing ground for not only styles and themes, but also for liberalised labour relations and, eventually, young talents. The studios eventually participated in the Pink industry through distribution and even production, and in turn exerted pressure and influence on the Pink industry to organise and standardise. This process was cemented by Roman Porno’s triumph and the appearance of an exclusive Pink film distribution/exhibition circuit. Ironically, Nikkatsu used its Roman Porno success to remain the only one of the surviving majors to maintain a vertically organised studio system, while the other majors became distributors/exhibitors that coordinated a highly liberalised production sector. Just as ironically, the Pink film industry is presently the only section of the Japanese film industry to still employ a strict seniority system in training and production. Directors are, in practice if not in a contractually formalised way, bound to certain producer/distributors. Once a radical reservoir for stories characterised by ambivalence and sexual violence, and economic strategies that threatened the film world’s status quo, Pink film has largely become an archive for remnants of the world it once seemed to oppose. This is not to say that there are not still ambitious and challenging Pink films being produced. But it increasingly seems that further survival will entail breaking out of the Pink screening spaces that once preserved it and increasingly isolate it. What will then be found on DVD racks, in art-house theatres and on the Internet will conceivably not be Pink film any more.