Since its inception in 2006, “The Smoking Cabinet: A Festival of Burlesque and Cabaret Cinema 1895–1933’ has run highly-successful micro film festivals, it has occupied a residency in one of the UK’s leading independent cinemas, the Curzon Soho, and also gone on tour at music and film festivals throughout the UK.

The festival was born, and has continued to grow, during a period that has seen a clear renaissance in social, cultural and critical interest in cabaret and burlesque. Opportunities to both watch and actively participate in this renaissance have opened up in social clubs, music venues, dance schools and nightclubs across the UK, specifically in London.

Despite this resurgence of interest in burlesque, cabaret and vaudeville, the fact that all of these forms found a natural home in early cinema, and were often also the focus of early experiments in filmmaking, is often overlooked. It’s ironic, therefore, that the relationship between dance, the body and the moving image has been explored extensively and is clearly established within cinema history in other contexts. Distinguished by tableaux and static shots, early cinema emphasised performance within the frame and basked in the novelty of filmed movement, both as spectacle and also as a form of entertainment in its own right. The fit then between film, dance and performance was explicit in cinema’s nascent years, simply due to the limited technical sophistication of filmmaking at this time. In acknowledging and exploring these issues, the festival offers a unique opportunity to better understand and experience the intersection between burlesque, cabaret culture and the medium of film.

Many of the films screened by The Smoking Cabinet have been either largely forgotten or have simply been inaccessible to the majority of cinema-goers, film fans and arts lovers for decades. The Smoking Cabinet offers a rare chance to see an eclectic range of films with occasionally risqué and suggestive burlesque and cabaret content within a festival that strives to position these films within a specific context. It is arguably contradictory: a specialist film festival aimed at a potentially wide-ranging audience. However, as will be discussed in more detail below, there is in fact a large and diverse audience for a festival that exhibits the alliances that silent and early cinema had with variety, burlesque and cabaret performance.

Thus, many of the films programmed by The Smoking Cabinet represent examples of the most significant films in the history of sexuality and sex on screen from this period, whilst others offer a similar insight into the history of dance in film. Although considered somewhat tame by today’s audiences, these influential films and their memorable erotic scenes were both groundbreaking and controversial at the time they were produced. A look at some of the films programmed reveals the extent to which many challenge sexual politics of the time and highlight the representation of sexuality during this period.

WOMEN WHO DANCE, GIRLS WHO GAZE

The earliest known pornographic films began to appear in France in the early 1920s and were known as ‘risque’ films, sold on the black market and viewed mostly in private settings. Lesbianism and heterosexual intercourse were the most common subjects of these films, whilst depictions of male homosexuality were extremely rare. To date, The Smoking Cabinet has not programmed a compilation of ‘early pornography’. However, in the process of researching countless explicit films that would certainly be considered graphic, even by today’s standards, were identified.

Whilst explicit feature-length ‘pornographic’ films are not considered to have emerged widely until the 1920s, there was nonetheless a tradition of representing titillating or suggestive material on film even from the very first years of cinema’s invention. For instance, the festival has focused on films such as Fatima’s Coochie-Coochie Dance (Edison Manufacturing Co. 1896), a short nickelodeon film of a gyrating belly dancer named Fatima. Fatima became well-known following her dancing shows at the World’s Exhibition in Chicago, USA, in 1893. Fatima’s Coochie-Coochie Dance is notable for being the first film to be subjected to censorship. It was specifically the sexually suggestive nature of Fatima’s gyrating that was objected to and this was covered up, albeit slightly ineffectively, with a grid-like pattern of white lines. Fatima and her dance is an superb example of the numerous risque films that featured exotic dancers during this period.

Other films, such as a Trapeze Disrobing Act (George S. Fleming, Edwin S. Porter, 1902), in which American vaudeville trapeze artist and strongwoman ‘Charmion’ strips from full Victorian outré wear to her knickers in less than one minute, whilst still swinging on her trapeze, are a triumph of early cinema. They present erotically-charged examples of female sexuality speaking predominantly to male audiences. This has lead some theorists to argue that these films can be understood as representing one very specific perspective in terms of the act of spectatorship, namely ‘the gaze’. Whilst it is true that the image and eroticisation of the female form was crucial to the success, and immense popularity, of these early forms of entertainment, there are examples of films featured in the festival that do still recognise women as agents of change, in dominant roles, and negotiating situations on their own terms. This can be said of not only the characters they played but also of their position as ‘celebrities’ in the real world.

The dancing vaudeville performer Annabelle Whitford Moore was also featured in many of the earliest nickelodeon films. Known popularly as ‘Peerless Annabelle’ her routines were famously captured by the film pioneer Thomas Edison. Annabelle Butterfly Dance (William K. L. Dickson, 1894) was one of her most well-known performances, but her output was exhaustive and she also featured in Annabelle Sun Dance (Edison Manufacturing Co., 1894), Annabelle Serpentine Dance (Edison Manufacturing Co., 1895), Serpentine Dance by Annabelle (William K. L. Dickson, 1896), Annabelle in Flag Dance (American Mutoscope Co., 1896), Skirt Dance by Annabelle (American Mutoscope Co., 1896), Tambourine Dance by Annabelle (American Mutoscope Co., 1896) and Sun Dance – Annabelle (Edison Manufacturing Co., 1897). Male audiences were enthralled watching these early depictions of a loosely-clothed female dancer through a kinetoscope, the ever-popular peep show device often used to view short films in this period. These devices operated conveniently in terms of spectatorship allowing the audience to view risqué dances or suggestive films discreetly, and certainly helped fuel perceptions of the eroticism of star performers such as Annabelle Whitford Moore.

The Smoking Cabinet has also screened the Ernst Lubitsch’s extravagant spectacle So this is Paris! (1926). The film features a cast of hundreds of performers dancing the Charleston beneath a pair of giant plastic legs. The avant-garde film Oramunde (Emlen Etting, 1933) features a mysterious nude-in-nature and Jean Renoir’s controversial Charleston Parade (1927) stars African-American vaudeville performer Johnny Hudgins and Catherine Hessling (in a fur bikini) engaging in an early form of ‘dance-off’, a celebration of the 1920’s most popular dance craze the Charleston.

As well as classic shorts, The Smoking Cabinet programmes feature films, most notably Piccadilly (1929) and Der blaue Engel (1930), director Josef von Sternberg’s first collaboration with the legendary Marlene Dietrich. This was also accompanied by a panel discussion ‘Women in Burlesque & Cabaret: Empowerment vs. Titillation’ which addressed how and why a seemingly male-focused art-form has become a popular form of expression for so many women. The panel considered whether these forms offer a political platform for female performers to explore issues of gender and sexuality or whether they simply reinforce traditional notions of female sexuality. With this in mind, the film, appropriately, tells the story of a meek and repressed teacher, Professor Immanuel Rath (Emil Jannings), who is seduced and destroyed by a sensual and predatory top-hatted entertainer named Lola at the Blue Angel nightclub. The recent restoration of E. A. Dupont’s Piccadilly has also been timely, given the current burgeoning of the New Burlesque movement. Piccadilly explores the dividing line between empowerment and exploitation. It boldly challenges 1920s taboos in its celebration of feminine wiles, and exotic Anna May Wong’s transformation from scullery girl to burlesque diva and dancer par excellence enthralls the audience.

CABARET CULTURES AND CULTURED CINEASTES

The principal aim of The Smoking Cabinet is to investigate the legacy of early cabaret, vaudeville and burlesque forms in cinema between 1895–1933. Starting with the birth of film in 1895 and closing with the end of the Weimar Republic in Germany in 1933, four years after the coming of sound to cinema, it encompasses a period of considerable innovation in art and technology throughout Europe and America. During this period the ‘modern world’ emerged. It was a time of phenomenal developments in all aspects of modern life, including major socio-political changes. Set against this backdrop the style and technique of filmmaking also rapidly evolved. Filmmaking was transformed from being tableaux in composition, with static shots and long unedited takes, to continuity editing, synchronised sound and the emergence of the studio system whose model of producing, distributing and exhibiting film we still broadly recognise today. Early cinema, which by virtue of its ‘newness’ was both experimental and seminal, offered its audience a glimpse into the unknown and brave new world of mass visual entertainment. Cabaret, burlesque and film all emerged to become major forms of popular entertainment. During this period, the alliances between these forms were often explicit, with early film shows essentially taking the form of variety programmes interspersed with short films. In watching examples of these films The Smoking Cabinet festival’s audience are able to imagine what it must have felt like to be positioned on the brink of modernism; expectant and excited about the rapidly changing world evolving in front of their eyes.

Cabaret reached its peak during the Weimar Republic of the late 1920s and early 1930s, although it has always been an art form that has fascinated its public. In this respect The Smoking Cabinet aims to do something that cabaret as an art-form does; to present a mixed bill of exotic and eclectic acts and entertainment. The Smoking Cabinet programming is, therefore, by definition eclectic. The selection of films poses a question: it does not aim to dictate what can be understood by the idea of cabaret and burlesque film, but asks ‘what can be understood by the term cabaret and burlesque cinema?’ Programmed material includes the work of leading and revered filmmakers such as Georges Méliès, Man Ray, highly influential work by the Dadaists, Percy Smith, Fred Evans and Adrian Brunel. Exceedingly rare footage such as Moody’s Club Follies (Castle Films, 1923) was also featured at the festival with original footage from a 1923 revue performed in London along with content featuring music hall stars such as Elsa Lanchester and lesser-known curiosities including late-nineteenth-century erotica, trick films and novelty shorts.

Some of the material programmed could certainly be classified as documentary or reportage in a broader sense and several of the featured films were initially intended to be light-hearted news items. One of our headline features of the 2008 festival which included several examples of this type of film was our Coney Island programme. This also included Fatty Arbuckle and Buster Keaton in the 1917 classic Coney Island (Fatty Arbuckle, 1917). The Coney Island programme offered a wonderfully eclectic mix of curiosities, with the King of Coins (Alf Collins, 1903) sharing the bill with both ‘boxing cats’ and the muscle man Eugene Sandow, one of the first entertainers in America to have their reputation enhanced by the moving image.

As well as recording the performances and culture of cabaret and burlesque during this period the films programmed for the festival also reflect the art-forms that influenced society at large. One could argue that Percy Smith’s classic film Birth of a Flower (1910), featuring blossoming flora, has little to do with cabaret or burlesque. However, bursting with suggestive sexual allure, it is a subtle tease in cinematic form. Films such as this encourage the audience to consider just how far burlesque and cabaret cinema extend, and thus engage more wholeheartedly with what they are viewing. Whilst some of the films selected for the festival are more subtle and allegorical in their relationship to cabaret and burlesque performance, others are most certainly not. For instance, the burlesque qualities of a title like Disrobing Trapeze Act require little interpretation. The point here then is that the content programmed for the festival is at times as disparate and diverse as the cabaret and burlesque scene itself. And, of course, this is what gives the festival its edge and excitement. The festival is a showcase for potent, stunning and previously unavailable films that have inspired artists, filmmakers, performers and dancers of the past. It is hoped that all the films programmed encourage a deeper understanding of the relationship between cabaret, burlesque and the evolution of early cinema.

STAGE-MANAGING THE SEDUCTIVE

Not surprisingly, agreeing on the content for the festival was a subject of keen debate amongst the four producers who as a team also had responsibility for fundraising and sponsorship, PR and Press, copy-writing, design, event running and production. A large part of the material programmed hails from the British Film Institute and the National Film and Television Archive. Journalists often have a nostalgic view of what archive film programming entails; imagining the programmers brushing off dusty film tins and ‘re-discovering’ long-lost classics. In actual fact it involves endless research on databases, dead-ends, and the relentless pursuit of individuals and companies for rights clearances. We have searched thousands of database entries and titles in order to find content for the festival, and this is an on-going process.

Our searches began initially with research into ‘the smoking concert’ films – a collection of mild erotica made for male audiences around the turn of the last century. As it transpired, many of these films were either inappropriate, unimaginative or incomplete. Our research has also focused on circuses, trapeze artists, striptease, magicians, burlesque acts, comedy duos, stage shows and music hall stars. We embraced search terms and subjects that reflected the diversity of cabaret, burlesque, vaudeville and music hall entertainment and this in its self required extensive research on these subjects in order to learn more about the star performers of the time. Lisa Appignanesi, the patron of the Smoking Cabinet and author of The Cabaret (Yale University Press, 2004) was a huge help here. Her book features extensive accounts of the origins of these forms, from 1880s politically motivated chanson singers and literary cafés in Paris, through to the Weimar period and beyond. Research for festival content is always followed by lengthy viewing sessions – often operating Steenbecks for the screening of shortlisted 16mm and 35mm film in the depths of the National Film & Television Archive. This in itself raises an important question of how The Smoking Cabinet producers choose to define cabaret and burlesque cinema. The answer is to avoid any approach that may put a limit on what it has, can or may mean. We chose to consider it as an attitude as much as an act – a projection of spirit as much as literal performance. This wide embrace is best captured by the magazine Dazed & Confused’s description of the festival as ‘deliciously eclectic; the ultimate tease in film festivals’.

The Smoking Cabinet offers not only screenings, but also the opportunity to see live performances, music, discussions and workshops. Debate and audience participation is evident at any Smoking Cabinet event, whether in the form of traditional panel discussions, Q&As following screenings, detailed introductions or informal group discussions. The festival generates a significant amount of debate between professional performers, film historians, archivists and the general public, and this is key to both its vitality and the atmosphere generated during the festival. This interest in discourse has also been encouraged through podcasts conducted by The Smoking Cabinet. These podcasts, which feature interviews with leading figures in the contemporary cabaret and burlesque movement, are available on The Smoking Cabinet website (www.thesmokingcabinet.com). The festival offers a platform for observation, understanding and debate, as arts practitioners, performers and entertainers who use cabaret or burlesque in their work take part in a series of post-screening discussions. The topics covered include issues such as representation, the body, women and the role of migration in early cinema, as well as inevitable debates around sexuality, form, Otherness, aesthetics and the growth and future of cabaret and burlesque itself.

The Smoking Cabinet is, however, still modest in size, attracting approximately a thousand guests each year over a three-day period, with on average six or seven screenings and events. The major challenge in our first year was funding. This did not come as a great surprise in a climate of increasingly curtailed funding for the arts, but the obvious effect of this was simply that in our first year we had to scale back both our budget and our ambitions for the festival. Practically speaking, this meant cutting workshops, ensuring that all screenings were at one venue and reducing the number of screenings. In our second year we were able to introduce workshops and expand on our efforts due to the fact that we secured sponsorship from a boutique lingerie company, Playful Promises. We have developed other partnerships which have allowed the festival to grow, receiving support from Westminster Arts, 10th Planet Digital Media and importantly the British Film Institute and the National Film and Television Archive.

The festival has consistently made efforts to go one step further and ensure that we host ‘events’ and not just ‘screenings’, with the aim of providing real value for our audiences. The cinema exhibition model is changing rapidly. Developments in technology and the growth of the DVD markets and downloads are affecting how and when we watch films and this has often meant that cinema audiences can, at times, be elusive. In many cases it is no longer possible to simply programme a film and anticipate that this in itself will be enough to woo an audience. This is specifically true of attendances for repertory screenings, which have dropped dramatically in recent years. It is this fact, coupled with a desire to offer screenings and events that are genuinely unique and exciting, that has guided the festival. The Smoking Cabinet regularly transform and extravagantly decorate the venues used for the festival and guests have also embraced the spirit of the festival by donning vintage and burlesque clothes. We have hosted DJs and numerous live burlesque performances, staged musical cabaret acts and preceded film screenings with specially commissioned and bespoke burlesque performances. We also produce extensive programme notes for all screenings in order to contextualise the films screened. We have recreated the seaside fun of Coney Island with typical seaside amusements and ice lollies, and have also re-created the feel of a 1920s gin palace for our opening night in 2008. We have had DJs play from vintage gramophones, and have hosted free education events and dance workshops.

Enhanced financial support in 2008 enabled us to introduce both the education dance workshops that we had hoped to offer in our first year. The education workshop was hosted by our sister organisation Mirror Mirror. This was established early in 2008 to enable us to offer educational events centered around early cinema; naturally risqué content could not be featured in these workshops which directly led to the formation of a sister company in order to keep this project separate from The Smoking Cabinet. The workshop was focused on one film, a short comedy made in 1910 called Vice Versa (David Aylott). A young boy steals a magician’s wand which miraculously upsets the social order to funny but culturally poignant effect. The education event was used to investigate the types of characters and situations presented in the film, leading to further investigation into genre, social structure and stereotypes. Comparing and contrasting the screening with life today illustrated how things have changed in a hundred years. The education event was hosted with Film Education and proved extremely popular, with full attendance. Mirror Mirror is a strong example of how fluid events and film programming can be and as an initiative has continued to grow at an impressive rate. Mirror Mirror offers school children an opportunity to see rare examples of early cinema and contextualises them with the same energy and enthusiasm harnessed by The Smoking Cabinet, using the history of entertainment and the moving image to investigate the past and present in a fun and atmospheric way. Mirror Mirror has now extensively toured schools and organisations across the UK (see http://mirrormirroreducation.wordpress.com).

The dance workshop, enabled by additional funding, was hosted as part of The Smoking Cabinet by a group called The Bees Knees and focused on basic moves used in the Charleston. The session commenced with a very gentle warm-up routine and participants were then introduced to simple steps, followed by a routine – to which they were encouraged to add their own variations during a collective dance party at the end. The dance workshops took place on the same day as The Smoking Cabinet’s On With The Dance programme and proved a great opportunity to get moving, explore dance and celebrate physicality in film. We hosted two workshops, both of which were free to those who wished to take part. Such workshops add not only to the sense of occasion, but have developed and encouraged greater audience engagement with the festival.

FUNDING THE FLIRTATIOUS

Organising a public festival with funding and support requires reporting and analysis of the festival and its operation. We evaluated the festival by encouraging all ticket holders to complete surveys in order that we could get direct feedback. We made sure our audiences were aware that we wanted to hear their opinion not only on what they thought we did well, but also on the things we could improve on. To our delight, feedback forms from the festival have showed a positive response of 95–98 per cent of audience members. In producing funding applications and in asking organisations to support us we have also had to be extremely aware of who our audience would be and in this we found ourselves lucky – during this process we discovered our audience had the potential to include a wide range of people and it is this fact that has helped us generate strong ticket sales and sell-out screenings.

The festival speaks to all people interested in the moving image and those film fans who want to access rarely-screened cinema. As well as being a centrally located art cinema that draws people from across London, the Curzon Soho is also a local cinema catering to the needs of the local community. Soho supports many of the performers and artists who continue to develop and nurture the tradition of cabaret and burlesque in London’s West End. The gay community also comprised a notable part of our audience demographic, having traditionally embraced cabaret and burlesque. The festival also drew an audience of fans of dance and performance, those with an interest in social histories and representation, as well as those working in the performing arts community.

We broke down our target audience principally, though not exclusively, into the following groups:

1. Crossover neo-burlesque fans; young people (19+) seeking something unique and culturally fresh.

2. Early cinema fans; cinephiles, historians and academics (of film, of London, of music hall and cabaret) and teachers.

3. Locals from Soho’s diverse communities.

4. Westminster and wider London’s gay community

5. The avant-garde, burlesque performers, retro-obsessives, fashionistas.

6. Independent cinema fans, interested in discussion-based events and the chance to see early cinema.

7. Students of film and media studies.

Knowing your audience is key to good marketing and of course marketing is also key to ensuring that your festival has an audience. As well as targeting the groups identified above, The Smoking Cabinet was fortunate to be featured in a wide range of publications, from The Guardian to Dazed & Confused, and The Metro to Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour. We also consciously sought coverage in London’s weekly free website and email listings, from LeCool and Urban Junkies, to Kulture Klash and Daily Candy. These mailing lists go out to recipients in their hundreds of thousands. The news media were drawn to the novel nature of The Smoking Cabinet festival and, as a result, we found we had a proposition that people were very eager to feature, whether it be online, in print or on the radio.

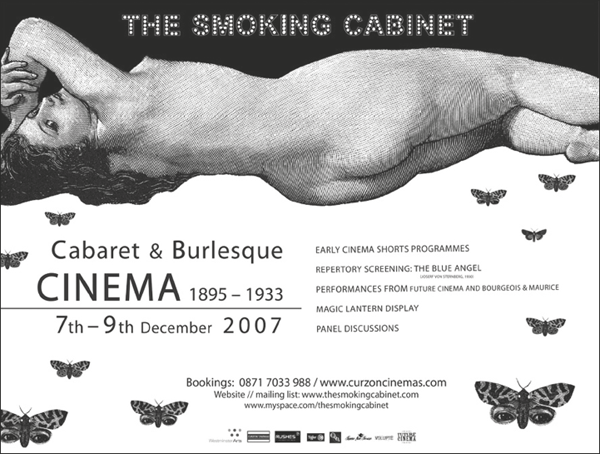

FIGURE 18.1 Our main poster from the first year of The Smoking Cabinet

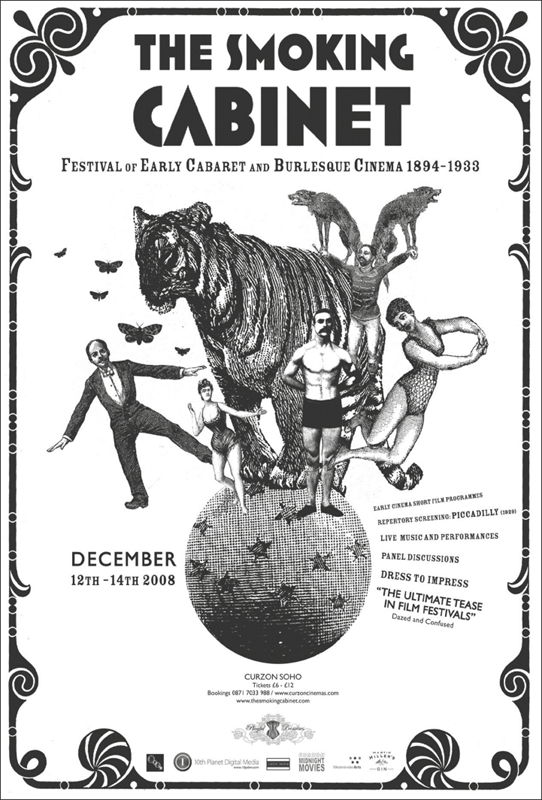

FIGURE 18.2 Our main poster from the second year of The Smoking Cabinet

Our marketing would not have been half as successful were it not for the fantastic design work of Kate Grove, a graphic designer and also one of the producers of The Smoking Cabinet. The design work for The Smoking Cabinet has developed over time allowing the development of a distinctive and unique feel each year. The design work, however, maintains a level of continuity in the key themes and focuses of the festival. The image of the butterfly with eyes ensures continuity between the designs for the two festivals, and has been something we have continued to deploy, whether on promotional badges, in flyers for the festival, or one-off follow-up events.

The festival comes together over the course of the year, and during that year we also work on The Smoking Cabinet’s guest appearances at other festivals and events. In essence the year breaks down into two parts: planning and research, lasting eight months; and production lasting four months. In the former we ask: What will we host – in terms of scale and style? What will we programme? Who are our target audience? What will we charge? How will we fund it? How do we market the festival? How will it stand out/why is it unique? Answering these questions allows us to formulate a clear strategy around marketing, programming, rights clearances and fees, design, funding applications, press and PR. With all these bases covered it is onto production and actually hosting the festival. In the four months before the festival we focus on sponsorship, audience development, press releases, additional marketing, finalising the programme, festival logistics and event running, decorating venues, and booking DJs, cabaret performers, acrobats and live musicians.

The Smoking Cabinet offers a model of how to produce a distinctive and unique festival within a film exhibition culture where, if anything, there are perhaps too many festivals. It’s a model of how, with passion, dedication and a lot of commitment, something unique can be created on a shoe-string, generating momentum and excitement not only for its audience but also those people producing it. Perhaps one of the enduring triumphs of The Smoking Cabinet is that each year the festival is produced for less than £2,000.

One of the highlights of the festival has certainly been hearing the audience’s reaction to rediscovering those films which have been locked away from public viewing for years. The spontaneous laughter, clapping and even cheering was truly heart-warming, and vindicated our belief that the concept for the festival could be successfully realised. This was matched by the amazing live performances and music, and the quality of speakers the festival offered. In terms of attendances, the festival has exceeded expectations, with our opening nights and performances repeatedly selling out. With an eclectic mix of forgotten cabaret classics, rare burlesque cinema, stimulating discussion and naughty-but-nice live performances.