As Eric Schaefer states in Bold! Daring! Shocking! True!, ‘sexploitation films can best be described as exploitation movies that focus on nudity, sexual situations, and simulated (i.e., nonexplicit) sex acts, designed for titillation and entertainment’.1 If Schaefer’s definition is assumed to be absolute, then Anna Biller’s film Viva (2007) is notably ‘Other’. Biller’s film, which tells the tale of a suburban 1970s housewife (Barbi) attempting to ‘live’ the sexual revolution, is filled with fun, frolics and fantasy vignettes. Additionally however, Viva is also a very serious, striking commentary which seeks not only to visually seduce the contemporary viewer, but significantly, to mentally stimulate them. While purposely spoofing the décor and cultural zeitgeist of the sexual revolution in America, Viva is consciously multi-layered. Despite frequent au naturel episodes, Viva is not a film designed only to sexually arouse or titillate (notably the action is cut before things get too hot), but can be understood as a text that focuses on nudity, sexual situations and sex acts in order to critically inform; to offer the viewer a different perspective, a different way of seeing sexploitation. Ultimately, Biller consciously plays with semblance, female servitude and shattered dreams. That is to say, her film sketches the solitude of the sexual revolution for both women and men.

Viva demystifies and makes visible the alienating and often ignored notion that sex in the 1970s was a sign or act of liberation. Via distinct narrative strands and clashing, multi-textured décor, Biller over-exposes the generic fantasy elements of s/exploitation cinema, screening and situating Barbi’s journey amidst fashion photography, nudist camps, naughty neighbours and Playboyesque orgies. Barbi (notably played by Biller) is on a personal journey in Viva which can be seen as partially parodist, or more specifically, socially satirical. Often delivering her lines in a purposefully ‘flat’ way, Biller represents Barbi as naïve, narcissistic and initially nescient. While the purpose of this representation is always arguable, I suggest that Biller’s representation of Barbi is politically informed. Unlike her female fun-loving neighbour in the film, Sheila, Barbi is a woman who desires something more (than preparing Playboy’s latest recipes for her handsome husband, Rick). Longing for the liberation that sex promises, Barbi is dissatisfied and forced to come to terms with both the myth of the sexual revolution as purely pleasurable and her status as the exotic other in suburbia. Biller’s text then engages most pertinently with the themes of ‘representation’ and ‘possibility’ enabling political debate in the fields of gender, visceral desire, genre and spectatorship.

VIVA AND ITS REPRESENTATIONS

On a general level in the filmic medium, representation pertains to the construction and composition of aspects of ‘reality’. Viva, existing as a period piece, realises, recreates and situates an authentic, effectual vision of exploitation movies from the 1970s. This is significant for several reasons. Firstly, filmic representation inherently involves a process of selection. Moreover, representation here stands in for and takes the place of what it represents. Biller, speaking of Viva, continuously notes the significance of her own experiences as a woman and relates these to the complexities of a ‘gender problem that’s universal and will always exist’.2 While purposely recreating the pseudo-psychedelic vogue of the 1970s, Biller makes visible the episodic and excessive nature of the sexploitation film. That is to say that she represents the purposeful deformation of naturalness as a desired filmic style, and highlights the deformation of the traditional gender divide in relation to new desires (particularly female desire) for freedom; for something authentic; something more than domesticity. The authenticity of the text then is arguably attained through psychological realism. Barbi is represented as confused, bored, alienated and a little absurd, noting at a hippie nudist commune: ‘I don’t want to be a man’s play-thing.’ Barbi thus appears to search for an authentic experience associated with sex and perhaps, this is indeed, the greatest success of Viva. Notably, Barbi fails (of course) to find jouissance. In lieu of the Thing, she realises her own existential authenticity. As Tanya Krzywinska, author of Sex and the Cinema (2006) notes, sex and the representation of sex onscreen is often far from idealistic. Instead, sex and the complexities of sexual relations upon the individual are represented in order to highlight the thorny, unsettling effects of the social order:

A key motive behind the use of psychological realism, is to show that sex is a physical and problematic business. Realism is often used in films that focus on sex in the light of problems originating within the social order, and, in some cases, facilitate the demonstration of the effects of a hierarchical differentiation in the exercise of power.3

An additional motif of differential power positing can also be read into the continuous, obnoxious laughter of the diegetic characters. This dominant laughter can be decoded as a political comment on, and direct response to, some audience members who have one-dimensional expectation of Viva. In essence, the laughter could be understood to be directed at what Biller calls people’s pre-conceived notions of the film as a ‘bad’ sexploitation movie. Commenting directly on this Biller asserts that

This movie has been dismissed by many distributors … because they see it as a trash film. The sexploitation genre is generally considered to be unsuitable for film festivals, and yet my film is not sexploitation, it’s quoting sexploitation… I think a lot of them [distributors and audience members] can’t understand where I’m coming from. A lot of them think, ‘She’s just doing an exact copy of a sexploitation movie. Those movies are so bad, why would anybody want to copy them?’ They don’t consider that the gesture of being a female making a sexploitation film and putting her in it makes it different. It’s confusing because it looks and feels the same, yet it’s completely different because of the context and point of view.4

The point of view Biller speaks of concerns representation. Viva is an indie film, directed by a woman. Continuously, it is the male rather than the female body that is situated and exhibited as the object of the gaze. Rick, Barbi’s husband is the visible object of demand in the film. His shirtless torso so desired by Barbi operates in order to drive her desire for more. Yet, like the audience, Barbi is repeatedly disappointed. Reflecting the lengthy but non-explicit structure of the film, it can be supposed that on one level, Rick fails to live up to his reputed phallic potency. His sexual encounters with his wife are not enough to sustain her happiness or prevent her ennui. Barbi, we learn, wants more of Rick’s time; Rick wants less of hers:

Rick: I’m going to extend my business trip to a month … This is important. If I don’t ski now, I won’t ski till next year.

Barbi: Why don’t you bring me along? I can learn to ski too.

Rick: Oh no, it’s not for you, you’d get bored.

Barbi: I’m so disappointed… You’re always working and I was looking forward to this vacation so that we could spend some time together.

Rick: Why are you always on my back? Can’t a guy just have some fun every once in a while? Look, Barbi, you’re being a ball and chain. I need to go in the outdoors and express myself – it’s who I am.

Barbi clearly finds the relationship inadequate. Rick fails to read her desire. Rick’s reference to Barbi always being ‘on his back’ is also significant. Barbi’s obvious sexual desire for Rick appears to be a discomforting experience for him. It can be inferred from Rick’s comments that he views skiing as a male sport, an active expression of his lone phallic masculinity. Considering the significance of psychological realism in the text as noted above, the theories of psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan could arguably inform a reading of Viva here. Lacan notes in Encore: ‘Phallic jouissance is the obstacle owing to which man does not come, I would say, to enjoy woman’s body, precisely because what he enjoys is the jouissance of the organ.’5

Barbi’s body and her jouissance, is represented as a complete mystery to Rick and moreover, to herself. Therefore, what is implied is some other knowledge, something that Rick is withholding from her. It is at this point that Barbi and her newly separated neighbour Sheila, decide to transform their own representations of self. Vocalising and then denying their self-blame, the women consciously dress in a sexy manner and set out on an episodic journey of self-discovery in the hope of discovering something more. The re-invention of their identities through alternate representations (as escorts) is again pertinent here. Barbi’s clichéd journey of discovery is informed by hope for another era in which she understands herself and is understood. As Frantz Fanon argues:

Representation is directed by a secret hope of discovering beyond the misery of today, beyond self-contempt, resignation and abjuration, some very beautiful and splendid era whose existence rehabilitates us both in regard to ourselves and in regard to others.6

This hope is undeniably embodied by Barbi’s new alter-ego – Viva. While Barbi fails to fit in, Viva, scantily-clad and hopeful, is determined to ‘live’.

MURKY MELODRAMA

The issue of generic and gendered belonging, or perhaps, more accurately, unbelonging is apt to discuss in relation to Biller’s text. Discomfort is not only addressed in Viva through the experiences and desires of Barbi and Rick, but also through Biller’s directorial style in relation to generic representations associated with gendered texts. As noted briefly above, Viva is absolutely episodic and as such can be understood on one level as a type of melodrama. Again here, realism is significant in a psychological rather than literal sense. The insights of Krzywinska are, as such, relative. Speaking of generic boundaries in relation to sex on-screen she notes that ‘in some genres, such as melodrama, aspects of realism may be employed to highlight the difficult relationship between the ideals of romantic fantasy and the harsh realities of sex and sexual relationships’.7 The formula that Viva follows (a formula of sexual discovery) can be contextualised via a soft-core aesthetic. That is to say, the soft focus employed by Biller, the stylised locations and rich over-exposed mise-en-scènic qualities of the text, function to legitimise and make visible the theme of negotiated, complex and conflicting sexual identities. Barbi, unlike Viva, is positioned as the sexual subject rather than the sexual object of the film. Viva can be bought. Barbi cannot.

The formula of Viva is dominantly consumerist, presenting explicitly the power of buying into a specific representation of the ‘American Dream’. Near the opening of the film, Rick and Sheila’s husband, Mark, discuss the possibilities of new technology (colour television) in a leering manner. This desire for ‘the good life’ is made explicit by the lines: ‘Live and love today and pay tomorrow – that’s the American way!’ The ‘American way’ is, of course, consumerist as referenced by Biller’s constant ironic inclusion of product placement throughout the film. ‘White Horse whisky’ is given a full-frontal close-up and is symbolically reinforced through a Jacques Demy-style interlude involving Sheila, Barbi’s white, bright neighbour, who utilises the spirit of the sexual revolution to dream-up her desires – a white horse, a rich sugar-daddy and a Cartier diamond bracelet.

The excessive nature of desire is arguably linked here to the notion of expenditure – an expenditure theorist Georges Bataille nominates as based upon a ‘principle of loss’. Writing of the dream of jewels, a dream Sheila again reinforces by stating: ‘I want to meet a rich man who’ll buy me a fur coat and diamonds – not like my cheapskate husband’, Sheila directly references the loss of her old self – Sheila the suburban settled wife. Interestingly, Bataille notes a connection between the dream of a diamond and personal loss or sacrifice. He notes: ‘When in a dream a diamond signifies … a part of oneself destined for open sacrifice (they serve, in fact, as sumptuous gifts charged with sexual love).’8 While Sheila is represented as happily invoking the loss of her marital body, Barbi appears initially uncertain. Discussing a potential new adventure as call-girls, Barbi and Sheila respond distinctly. Sheila sees the role of a call-girl as ‘romantic’: ‘I’ve always wanted to be a prostitute’, she says dreamily. Barbi, a little more cautious, invokes ethical questions regarding this type of consumerism and the ethics of it: ‘Isn’t prostitution morally wrong?’ she asks. ‘No Barbi’ Sheila replies, ‘it’s part of the sexual revolution – taking advantage of your new found sexual freedom.’ While Sheila renames herself ‘Candy’ – an edible treat that can be bought, Barbi renames herself ‘Viva’ – Italian, she points out, for ‘to live’ – a desire that we may infer to be part sacrifice, part adventure, part reality, part fantasy.

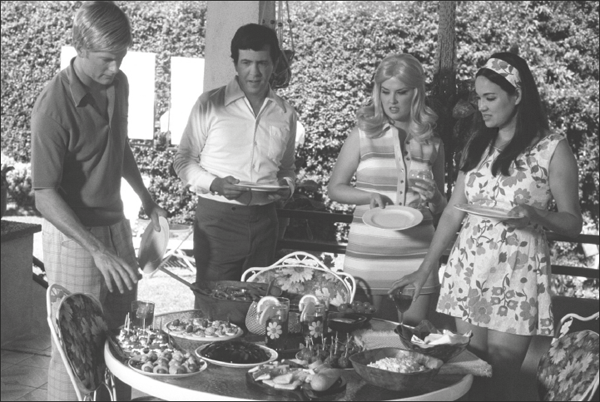

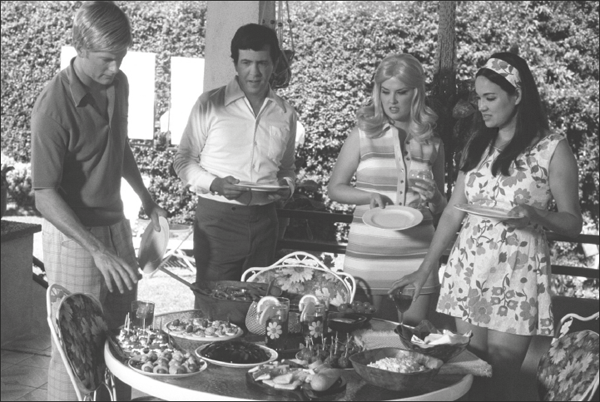

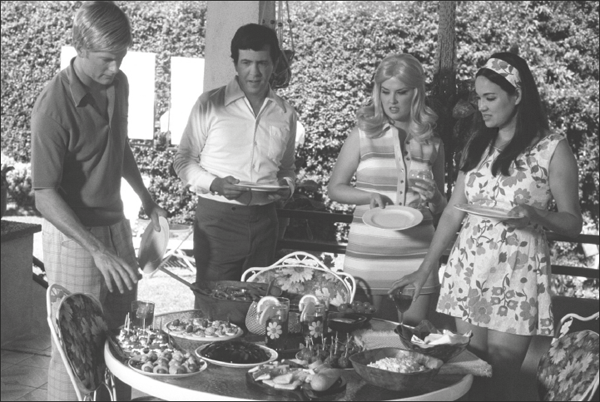

FIGURE 21.1 Viva’s sexploitation aesthetic: attention to 1970s style

The following journey of female sexual discovery is, as noted above, generically melodramatic. As Krzywinska notes however:

The social and emotional consequences of obsessive romantic fantasy that have real effects on the protagonist’s lives are primed to deliver a high-impact melodramatic experience. Through its focus on psychology and emotional effect … film is able to speak to audiences about the gulf between the reality and the ideal.9

While sexual discovery in film has long been associated with political change (in both negative and positive ways), Viva can be understood as a film that is distinct from the current sexual discovery oeuvre in several ways. Unlike films expressing the politics of sex such as Belle de Jour (Luis Buñuel, 1967), Deep Throat (Gerard Damiano, 1972), The Story of O (Just Jaeckin, 1975), Romance (Catherine Breillat, 1999) and Baise-moi (Virginie Despentes and Coralie Trinh Thi, 2000), Viva responds to and sits oddly between the pulp porn of Damiano and the avant-garde anger of Breillat. The film is neither solely a dreamy exploration of female sexuality nor a hard-core confrontation of sexual abuse. Instead, Viva is determinedly a text that refuses to ‘fit’ and this unbelonging has symbolic resonance. While disguised on one level as comedy, a quick scratch of the surface reveals its remarkable otherness. The thing that is distinctive and revolutionary about Viva is not the appropriation of gender politics and sexual inequalities in the 1970s, but rather, the fact that Viva, as a contemporary text, is informed by an understanding of identity as a historical transformation. As a period piece Viva juxtaposes irony and sincerity in order to simultaneously present, reminisce and reflect upon the romantisisation of the sexual revolution.

WRITING THE ORGY

Libertine living in Viva’s orgy scene positions Viva spectacularly, on-display. Drugged, in gold baroque costume and dancing to the beat of bongo drums, Viva interpolates a bacchanal frenzy. She becomes another (we infer) through the mind-expanding influences of drugs; another who lives for pleasure without reason. Her costume is, as always, significant here making visible the transformative nature of play-acting, the power of disguise (the orgy is ‘fancy dress’) and the sexual frisson of both voyeurism and scopophilia.

Through her costume, Viva becomes a spectacle; an object of desire that others are ‘turned on’ by yet, on the orders of the party organiser, Clyde, are prohibited from (fucking). The allure of transgression is associated with both Viva’s pending adultery, and Clyde’s regulation of the orgy here. As an object of fascination, Viva’s dance/song transforms her into an agent of both the erotic and the exotic. Alienated by her ‘otherness’ – as the primary object of desire – Viva acts out both the pleasure and pain of her struggle to find an authentic experience. Viva’s song nominates her ‘throbbing’ desires: ‘Do with me what you will’, she sings. The characters who surround her in this scene reiterate the visible exotic otherness of the orgy episode. Saturated with non-white characters dressed in loin cloths, the spell of otherness is only broken when Mark, Sheila’s husband and her white male neighbour, kneels before her and calls her by her ‘real’ name: Barbi.

Indeed, Clyde at this point physically alienates Barbi, ordering her to be taken into another room, stripped and placed on a bed. The audience are here introduced to a new form of expenditure. Barbi’s previous order for Clyde to ‘do with her what [he] will’ implies a turning over of rational control. Barbi’s conduct is thus to be associated with erotic willing abandon. This type of abandon symbolised by her complete nakedness in the following scene can again be read in a Bataillean manner. That is to say, Barbi’s naked abandon can be understood as a form of Bataillean eroticism: ‘a state of communication revealing a quest for a possible continuance of being beyond the self’.10 Again then, we see that Barbi, through Viva, is on a quest for an authentic erotic experience and this is, most poignantly, what the orgy episode exposes. Viva’s lack of speech while Clyde removes her remaining clothing and disappears out of the camera’s sight is also significant. In close-up we see Viva’s face repetitively going out and coming back into focus. This is accompanied by her deep breathing suggesting an unknown pleasure that is perhaps experienced (for the first time) through being given pleasure rather than giving pleasure to others. This bestowed gift is, however, followed by a scene that suggests full penetrative engagement between Viva and Clyde shot from above.

FIGURE 21.2 Song, dance and desire: Viva’s musical orgy number

FIGURE 21.3 Viva – spaced out and seduced after being drugged by Clyde at the orgy

Focusing upon a bowl containing three red apples next to the bed (one of which Clyde had already taken a large symbolic bite out of), Viva becomes transfixed. Her stare marks the beginning of an aesthetic and stylistic transformation. The apples become obviously animated, themselves growing mouths and teeth, one devouring the other two whole. The background, at this point a vivid pink/purple colour, then transforms into a psychedelic floral montage. The flowers then metamorphose again, become spinning tops before bursting (reminiscent of Linda Lovelace’s orgasmic sequence in Deep Throat) at which point Viva and Clyde are once again made visible on-screen. Their bodies are overlaid, however, by bright red animated droplets that run down the screen like bloody tears. The connotations of both pleasure and pain here are obvious perhaps reminding the audience of the authenticity of ‘real’ eroticism as both a ruinous, irrational and painfully unknowable experience.

THE NARCISSISTIC DEMISE OF ROMANCE

According to Lynne Pearce, romantic love is also painful and unknowable and can best be understood as ‘a heady cocktail of psychic drives, cultural discourses and social constraints … experienced by its subjects as a traumatic “impossibility” that is worse than irrational’.11 The notions of im/possibility and/or ir/rationality are significant to discuss here due to the excessive nature of Viva discussed above. Viva functions as an episodic narrative saturated with romance, dismay and decay. Notably, however, Viva is also a text that is contradictory, combining sexploitation tropes with more conventional, heterosexual love narratives. Irrationality and impossibility are rendered significant in the film through a recognition that ‘love does not live in the bedroom’. As Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari argue, desire is revolutionary; ‘that does not at all mean that desire is something Other than sexuality, but that sexuality and love do not live in the bedroom … they dream instead of wide-open spaces, and cause strange flows to circulate that do not let themselves be stocked within an established order’.12 The strange flows invoked in Viva, could be understood to function through the Barbi/Viva oscillation. Barbi/Viva is at once hopeful and disappointed, wife and adulterer, ordinary and extraordinary, rational and irrational. Happily liberated in one scene, Barbi/Viva is seemingly victimised in another. Barbi longs for romance, for sensitivity but, as Viva, seemingly enters into potentially violent or abusive scenarios repeatedly and to an extent, willingly. Romance or at the least Barbi’s romantic desires, are, via these assaults on Viva, shown to be flawed. As Krzywinska points out, ‘sex and romance is flawed because it resides mostly in fantasy and, despite the idealistic optimism … we never truly know the other’.13 In terms of Barbi/Viva, her narcissism is both absent and present at differing times throughout the film. Pointedly however, Biller’s own narcissism and naked voyeurism are unashamedly placed on display. Whether her fetishism is directed toward a by-gone era, a Playboy ideal, or a dream of revolution through new interpretations of the past, she undoubtedly produces a gaudy and pleasurable aesthetic. In terms of the audience, the pleasure of seeing a serious film director topless in her own film triangulates this already complex representation of negotiated identities and points to a desire of new, spectacular possibility.

Toward the close of Viva, Barbi and Sheila discuss their adventures, Barbi noting the darkness of her self-discovery. Some things are ‘probably best hidden’ she says. Referring to her/Viva’s activities (particularly at the orgy) as excessive she notes that: ‘It was too much … I became a female animal, made only for pleasure.’ Such a comment implies of course a loss of human rationality. Barbi’s dark reflection upon Viva’s experiences relates to an excessive irrationality for pleasure alone which does not sit comfortably with Barbi’s domestic role. It is at this point that a conscious distinction is again made visible between Barbi and Sheila. As a white woman, happy in and perhaps belonging to suburbia, Sheila exclaims that: ‘I don’t see what’s so scary about living for pleasure. I’ve done it all my life!’ Barbi, the exotic ‘other’ undoubtedly feels differently. Sheila then informs Barbi that she and Mark are pregnant. Barbi asks if she is sure that the baby is Marks. Again, Sheila’s reply displays Barbi’s otherness, her naivety perhaps: ‘Oh Barbi, you don’t really think I ever actually slept with any of the men at the agency do you?’ In response, Barbi tells Sheila that she envies her.

In the next episode of the narrative, Mark, having previously arrived at Barbi’s house intoxicated to find Rick still absent and Barbi alone, makes reference to the orgy at which they were both present. Exchanging views, Mark describes Viva as ‘abnormal’ and a ‘filthy lesbian whore’ – casting her as the perverse ‘other’. When Mark then attempts to rape Barbi, she bites him and he apologises and leaves. It is moments after his departure that Rick returns ‘home’ – smells Mark’s scent on his wife and storms out of the house again. While we, the audience see nothing apart from Barbi framed and dismayed in the open doorway of their home – we hear the screech of tyres indicating that Rick has been involved in a car crash. This detail is never explained; however, the next scene reveals Rick (with his leg in a medical cast), Mark, a pregnant Sheila and Barbi sat in the garden area – as they were at the opening of the film signalling a restoration of sorts.

The definitive idea of equilibrium as re-instated remains, however, questionable. Sheila, visibly pregnant, hands out Playboy canapés and Barbi notes that she must get the recipe so that she can make them for Rick (a domestic duty we saw Barbi undertaking at the opening of the film). While Mark and Rick discuss their new-found happiness (Rick declaring his enjoyment of his increased time at ‘home’ with Barbi, and Mark noting his impending fatherhood), Barbi, we infer has regressed back into the unfulfilling role in which the suburbia initially placed her. As such, the value of her journey – to ‘live’ the sexual revolution – is called into question by Biller.

This questioning of Barbi’s journey is enhanced by strong references to other sexploitation films. The next episode sees Barbi and her pretty blonde friend (now having given birth to a baby boy) performing at the theatre. Adorned in red sequin dresses, diamante chokers and white feather boas, the ‘girls’ are told by a theatre director, Arthur (previously known to Viva) to ‘give it everything’. Dancing and performing in unison, the girls tell the tale of their journeys – noting their ‘normality’: ‘We’re just two girls who have seen it all – things haven’t always gone the way we planned. We’ve got into some serious trouble, but trouble be damned!’ This musical number is both spectacular and fantastic. The girls sing of the significance of perspective noting that they can be ‘lovers, mothers, singers, swingers and friends’ depending on the ‘point of view’. Again then, the issue of perspective is raised and addressed directly in association with spectatorship. Yet this performance also functions to highlight the issue of gendered spectatorship. In this scene the ‘girls’ are singing to and directly performing for Arthur and Rick – an exclusively male audience. Arguably, this could be assumed to be Biller’s direct address to the (expected) male audience of Viva. The irony of the scene and the familiarity of it (as blatantly referenced through similarities to Jacques Demy’s colourful musical Les Parapluies de Cherbourg (1964) as well as earlier references to Radley Metzger’s musical scores and the episodic fantasy style invoked from Belle de Jour points to a political statement about the visibility and fetishistic status of women as performers in sexploitation films. As Biller’s film is ‘other’, it could be suggested that she is indeed pointing out the perverse desire of male audiences here. As well as making a clear statement about its otherness, Viva is a female vision: sexploitation from the ‘other’ (the female directors’ and female audiences’) perspective.

The problematics concerning Viva’s acceptance at film festivals as mentioned above was perhaps then not surprising for Biller. Indeed, her indie film can be seen to recognise and predict this through Barbi’s ultimate repositioning at the close of the film. While the musical sequence speaks of ‘arriving’, ‘Viva la vita – we’ve arrived’ Barbi and Sheila sing, the question that is left hanging is ‘where?’ Arguably, the point of Biller’s film is to make visible the fact that each woman who experienced or lived through the 1970s sexual revolution had a different experience which can neither be represented nor understood as wholly bad or good. It would appear that Barbi is ultimately shown to have gained confidence through her episodic self-discovering journeys; however, perhaps most significantly, Barbi has learned to ‘live’ with her situation, her marriage, her unbelonging. Barbi and Sheila do not arrive at jouissance, but at self-recognition of the absurdity of living in what Mark brashly describes as ‘a man’s world’.