1

A HOMELESS PEASANT BORN IN A FEEDING TROUGH: THE SCANDAL OF FOLLOWING JESUS

HE WAS AN UNMARRIED peasant who was executed by the state for treason. Many of his friends were criminals, sinners, thugs, and misfits. Few of them were religious. He got kicked out of his home church (or synagogue) after saying things that deviated from the status quo. He spent most of his time with drunks, gluttons, fornicators, and thieves. He was so close to sinners that the religious leaders thought he was one. And nearly everything he said and did made religious people mad —such as when he told them to turn the other cheek, love their enemies, and give their money to the poor.

Jesus —the Jewish prophet-king from Nazareth —was dangerous. He wasn’t tame. He wasn’t predictable. He wasn’t safe.

Even though he befriended immoral people, he upheld a moral standard that was so impossible to obey that he walked out of a grave for us to attain it. He wasn’t very sensitive to those seeking to follow him. He never eased anyone into the kingdom or said things that people wanted to hear. Jesus was a hard-hitting, enemy-loving, harlot-embracing, wild-eyed Messiah, who resisted doing things the way we’ve always done them. The biblical Jesus hits us between the eyes with truth and embraces us with tears when we disobey that truth. Jesus demanded that “if anyone would come after me” —that is, become a disciple —“let him deny himself and take up his cross daily and follow me” (Luke 9:23). As Dietrich Bonhoeffer used to say, “When Jesus calls a man, he bids him come and die.”[1]

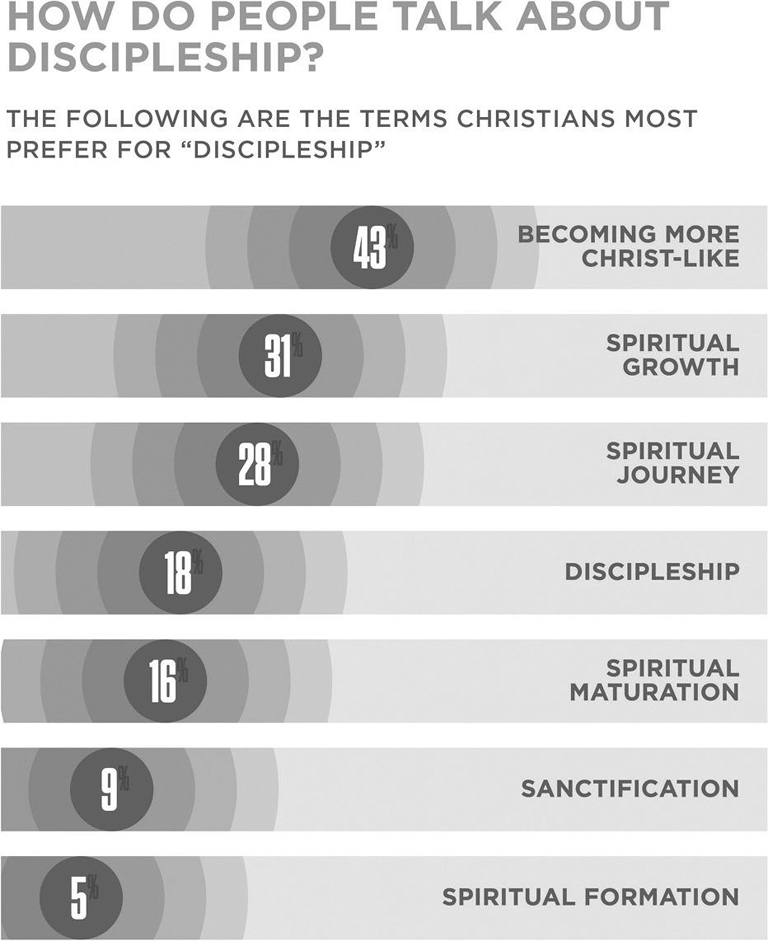

In this book we will explore what it means to become like Jesus, which means that it’s a book about discipleship. When we talk about “becoming more like Jesus,” we’ve got to slam our clichés on the operating table and dissect them to see if they’re biblical. And this book is going to serve as the surgeon. When we talk about discipleship and becoming more Christlike, we’ve got to keep asking: What does it mean to become like Jesus?

The Moral Jesus of Therapeutic Deism

As we’ll see, discipleship means becoming more like Jesus. This doesn’t necessarily mean we should sell our homes and walk around the streets as homeless peasants. But I do think we need to take a fresh look at the scandalous nature of becoming Christlike.

If I can be completely honest, I’ve never had a huge desire to write a book about discipleship (don’t tell my publisher). I just figured that all the pastors and churches in America are doing a pretty good job. And if it ain’t broke, why write a book about it?

But then I read the recent Barna study The State of Discipleship, and my desire to write this book was ignited.[2] In 2014, the international outreach ministry The Navigators commissioned the Barna Group, a Christian research firm, to perform an extensive survey of adult Christians, Christian scholars and influencers, and ministry and church leaders about their understanding and practice of discipleship. Some of the results of that study were informative; others were encouraging. But many of the results were depressing. We’ll unpack some of the depressing details in due time, but to sum it up: The American church is not doing very well at discipling its people. Which is a big problem since discipleship means becoming like Christ.

The State of Discipleship revealed that our methods of making disciples are broken. Whatever we’re doing, it’s not working. Few churches and Christian leaders are effectively helping people become more like Jesus. Reading the results of that study really fired me up to want to write this book. Once I realized that our methods of making disciples have proved ineffective, I decided to peek behind the curtain to see what was going on.

One of the problems I found was that many Christians who are trying to become like Christ are not becoming like the Christ of the Bible —that radical Jewish peasant-prophet from Galilee. Instead, they are seeking to conform to the god of moral therapeutic deism. And when I peeked behind the curtain (that is, read the Barna study), my suspicions were confirmed.

Moral therapeutic deism is a phrase coined by sociologists Christian Smith and Melinda Lundquist Denton in their groundbreaking book Soul Searching.[3] Their study was focused on the religious beliefs of American teens, but it captures the typical beliefs of many American Christians:

- God exists and watches over the world.

- He wants us to be good people who are nice to others.

- The goal in life is to be happy and feel good about oneself.

- God isn’t too involved in our lives unless we need him to solve a problem.

- Good people go to heaven when they die.

The God who exists in the minds of many churchgoers is “one who exists, created the world, and defines our general moral order, but not one who is particularly personally involved in one’s affairs —especially affairs in which one would prefer not to have God involved.”[4]

Of course, not every Christian thinks this way. But a surprising number do. My evidence for this used to be anecdotal —based on my own limited experience with other Christians. But then I read The State of Discipleship (and other studies like it), and my anecdotal experience was confirmed.

While many Christians say they want to become more like Jesus, the Jesus they’re imagining is largely a modern (and American) religious and cultural construct. He’s a Jesus who wants us to be good people, work an honest job, go to church as often as we can, be wise with our money, save up enough to retire well, raise well-behaved kids who don’t drink or party or have sex before marriage, and be nice to our neighbors while seeking justice for our enemies. But the short-haired, dark-skinned, unmarried peasant who received the death penalty for treason —the Jesus of the Bible —neither modeled this nor taught it. If we’re going to become like Jesus, we need to clear aside the clutter and see this Jesus for who he really is.

What Is Discipleship?

I’ve been a Christian for more than twenty years. This means I’ve heard the words disciple, discipleship, and discipling (a word unrecognized by Microsoft Word) at least 13 billion times. Like many Christian buzzwords, discipleship terms clutter the church airwaves, yet few people understand what they actually mean.

This could be bad news for a book about discipleship. We can’t get very far until we clearly know what it is we’re even talking about.

So what is discipleship? Is a disciple a special kind of Christian? Or one of the original twelve men who followed Jesus around in the first century? Can you be a disciple without being discipled by an older, more mature Christian? Is discipleship a program, a small group, a curriculum, a way of life, or something that only pastors and elders do? Are committed Christians disciples, while other less spiritual Christians are just plain old Christians?

The word disciple (Greek: mathetes) occurs at least 230 times in the Gospels and twenty-eight times in Acts.[5] According to the way it’s used, disciple is simply another term for Christian. We see this most clearly in Acts 11:26: “In Antioch the disciples were first called Christians” (emphasis added). Other passages (for example, Acts 4:32; 6:2, 7) use the term disciple simply to mean believer.

The terms disciple and discipleship aren’t unique to the New Testament. Many people in the ancient world considered themselves to be disciples or disciplers. The great philosophers of Greece often referred to their pupils —their learners —as disciples. In its most basic sense, the word disciple simply means “a learner” or “one who is taught.”

By New Testament times, the term disciple described one who was not just a learner but also devoted to a particular person, culture, or religion. Being a disciple meant being someone who followed and imitated the life and teaching of a great master. Discipleship was the process of learning from and becoming like that master. Plato was a disciple of Socrates, Zaleucus was a disciple of Pythagoras, and so on and so forth.

For some, “following” their master as a disciple might have been quite literal. The twelve disciples (also called apostles) named in the Gospels literally followed Jesus around in Israel. For others, being a follower of a master simply meant adhering to his teaching and seeking to imitate his life. The New Testament consistently uses the term disciple in this way: It describes all Christ followers, not some hyperspiritual subgroup who really takes this Jesus-freak thing seriously.

To be a disciple of Jesus, therefore, is to be a learner, an imitator, and a follower of Jesus. Discipleship is the process by which all Christians seek to become more like their Master. To be a Christian is to be a disciple, and every disciple —Christian —should seek to be like the Master.

According to The State of Discipleship, most Christians and Christian leaders agree —on paper —that “becoming more like Jesus” is fundamental to the Christian life. Yet on the whole, churches are not doing an effective job at making disciples who make disciples. Here are four pieces of evidence.

Christian Leaders Say “No”

According to the Barna study, only 1 percent of leaders say, “Churches are doing very well at discipling new and young believers.” A sizable majority —six in ten (60 percent) —feels that churches are discipling “not too well.” Contrast this with the responses of people outside of church leadership:

Christian adults, however, have a very different perspective than their leaders: 52 percent of those who have attended church in the past six months say their church “definitely does a good job helping people grow spiritually” and another 40 percent say it “probably” does so.[6]

So leaders say churches are not doing a great job, and non-leaders generally say they are. What do we make of this disconnect?

For one, I don’t think someone who has attended church “at least once in the last six months” will necessarily give the most accurate evaluation of the church’s effectiveness. Someone who goes to the hospital a few times a year is probably not the best authority on whether the hospital is doing a good job. I’d rather ask the doctors and nurses who are there every day doing the work. I’m not saying we need to canonize the opinion of church leaders. But I do think their analysis is closer to the mark.

The Barna study also shows how many people are engaging in what the study calls “discipleship activities.” “Despite believing that their church emphasizes spiritual growth, only 20 percent of Christian adults are involved in some sort of discipleship activity.” These activities include “attending Sunday school or fellowship group, meeting with a spiritual mentor, studying the Bible with a group, or reading and discussing a Christian book with a group.”[7] In other words, The State of Discipleship reveals that a relatively low percentage of Christians are involved in church beyond attending (most) Sunday services.

But then again, just because someone is attending a church program doesn’t guarantee that discipleship is happening. Some Bible studies are amazing avenues of spiritual growth. Others, though, are incubators for heresy, legalism, gossip, or cultic displays of power and control. I’ve been to some life-giving Sunday school classes. But I’ve also been bored to death by irrelevant and confusing monologues delivered —often read —by kindhearted but incessantly dull teachers. Or what if the college quarterback gets saved, starts leading a Bible study, and the attendance goes through the roof, especially among teenage girls? Are they wanting to grow closer to Jesus or closer to a guy with six-pack abs? God only knows. Certainly we can’t evaluate the church’s discipleship based merely on attendance figures.

Besides, what are discipleship activities anyway? Can we really determine whether people are “becoming more like Christ” based on their Sunday school and Bible study attendance? Did Jesus himself attend or put on any of these discipleship activities? Many churches today on the West Coast, where I’m from, don’t even have Sunday school. The single mom who works on Tuesday nights will find it hard to get to the church’s Bible study that meets on Tuesday nights. And what if I don’t want to attend a Christian book discussion group? Does this mean I don’t desire to “become like Christ?”

There’s nothing inherently wrong with these activities. They can play a vital role in one’s desire to become more like Christ. But we can’t determine whether a disciple is growing in Christ based on their attendance of church activities. Even if they are growing in their knowledge of Jesus through these activities, such learning should fuel their passion to live this stuff out. We must also do the work that Jesus calls disciples to do. Learning without doing is not really learning. We learn by doing, not just by learning alone. When Jesus said “come follow me,” he wasn’t heading to Sunday school. He was on his way to heal the sick, befriend a tax collector, stand up for an adulteress, and proclaim Good News to the poor.

Discipleship and mission go hand in hand. You can’t have one without the other. And mission —impacting the community for Christ —is most effective outside the four walls of the church. We’ll tease this out more thoroughly in chapter 7, so let’s move on to the second piece of evidence that discipleship isn’t working.

Millennials Say No

You may have heard that Millennials (people born after 1980) who were active in youth group are leaving the church in droves once they hit their twenties. According to David Kinnaman, “There is a 43 percent drop-off between the teen and early adult years in terms of church engagement.”[8] According to Rainer Research, 70 percent of active youth group members leave the church by the time they’re twenty-two years old.[9] Based on the current rate of departure, the Barna Group estimates that 80 percent of those raised in the church will be disengaged by the time they’re twenty-nine years old.[10]

Some people yawn at statistics like these. “Young people have always been less likely to attend [church] than are older people,” writes sociologist Rodney Stark.[11] When they grow up and have a few kids, they’ll come back. They always do. No need to fret or change the way we do church.

But that’s just it. They’re not coming back. Even though eighteen- to thirty-five-year-olds often have the lowest rate of church attendance, the dropout rates themselves are higher than ever before. And eighteen- to thirty-five-year-olds today live their lives much differently than previous generations. Fewer are getting married; even fewer than that are having kids. These, traditionally, are the life events that drive people back to the church.[12] If we’re waiting for them to settle down and return to church, we may be waiting for a while.

Not only that, but our Millennials are growing up in a world much different from previous generations.[13] The Internet alone has produced unparalleled shifts in how people live and think. Many sociologists have compared these changes to what took place after the invention of the printing press back in the fifteenth century. Just as information and literacy spread rapidly in the wake of the printing press, now information and power spread at the speed of light. We have little clue about the long-term social, mental, spiritual, relational, and civil impact this will bring. We stand right smack-dab in the center of the storm.

As we look at the trend of people leaving the church, we shouldn’t conclude that the sky is falling or that God’s kingdom is coming to a screeching halt. Jesus promised that the gates of hell will not prevail against the church (Matthew 16:18). God is on the move! Still, as David Kinnaman says, “The dropout problem is, at its core . . . a disciple-making problem. The church is not adequately preparing the next generation to follow Christ faithfully in a rapidly changing culture.”[14]

Some may say that people are leaving the church because they simply aren’t Christians. And this is certainly true in some cases. Churches will always have people who attend for a season but then realize that they’re not as much of a Jesus freak as they thought. The quarterback-turned-Bible-study-leader may put on thirty pounds; or he may leave the church, and his “followers” may follow him. But in many cases, people leave the church not because they had some beef with Jesus or were fly-by-night pseudo-Christians. “In fact, 51% of teens who leave the church in their twenties say they left because their spiritual needs were not being met.”[15] At least 23 percent say that they actually wanted to know more about the Bible when they were in church but didn’t get it.[16]

So they left. They left because they didn’t experience discipleship. They left the church to follow Jesus —that wild-eyed, hard-hitting, homeless peasant who told the rich young ruler to give all of his stuff to the poor.

People shouldn’t have to leave the church to find Jesus. But this is sometimes the case. Sociologists Josh Packard and Ashleigh Hope interviewed one hundred such “dechurched” folks —former lay leaders, active members, and congregants —for their book Church Refugees. Their study turned up surprising results.[17] They were expecting to find people who were burned out, overworked, or simply living on the sidelines of ministry. Instead, they found people who were still engaged, energetic, and desiring to make a difference in the world. Instead of being empowered by their churches in this desire, they were stiff-armed by bureaucracy or given a job that was restricted to Sunday services. As one dechurched Christian said: “There’s nothing for me to do there [in church] that’s meaningful.”[18] Many dechurched leavers were bubbling over with passion and imagination about how they could tangibly share the love of Christ with their communities. Packard and Hope sum it up:

The dechurched are leaving to do more, not less. The church isn’t asking too much of people; it’s asking the wrong things of them. . . . Jesus commanded his followers to care for the poor, the sick, and the hungry, [yet] the dechurched have experienced church as an organization that cares primarily for itself and its own members.[19]

Understanding Millennials and other dechurched Christians will be vital for our study. I’m going to make a case that many people would not leave the church if the church was doing a better, more holistic, and more creative job at discipling its people.

The Decline of Christians Says No

The exodus of Millennials from the church mirrors the overarching decline of Christianity in America. It’s difficult to determine who’s a Christian and who’s not. Only God truly knows. But according to several studies, the number of genuine Christians is way lower than most people assume.

Some think that a large percentage of Americans are Christians. According to a Gallup survey, 45 percent of Americans claim to be born again.[20] Other research shows that 76 percent of Americans identify as Christian.[21] But claiming to be something and actually living it out are two different things. I remember talking to an Iraqi friend of mine about his faith. “I’m a Christian,” he confessed. I got excited and probed a little deeper about his faith commitment. “Oh, I actually don’t believe in God,” he told me. For him, being a “Christian” was a cultural way of saying he wasn’t Muslim.

Just because some people tick off the “Christian” box in a religious survey doesn’t mean they’ve put their faith and hope in Jesus Christ. According to several independent surveys, the number of genuine Christians in America —who show some evidence of actually following Jesus —is around 8 percent.[22] According to George Barna, this percentage is down by about 30 percent since 1991. Pastor and author John Dickerson estimates that the percentage will be down to about 4 percent in the next thirty years if current trends continue. Reversing that trend is a discipleship concern.

Maybe you feel that your church or other churches in your city are growing. And maybe they are. But whenever churches grow, we have to ask where the growth came from and why it is occurring. That is, we have to distinguish between transfer growth and conversion growth. Conversion growth is when a church grows because people are getting saved and coming to church for the first time. Transfer growth is when people leave one local church to attend another. Transfer growth is not often the best way to measure whether discipleship is happening. It’s not all bad, but it’s not all good either. After all, Jesus never commanded his followers to “go into all nations and transfer Christians from one church to another.”

If your church is growing because other people are leaving another church and coming to yours, then you still have to ask the discipleship question: What are those other churches not doing in discipling their people? And how will your growing church disciple these new members? Many newcomers stick around for a while but then move on after the new-church buzz wears off.

The Biblical Illiteracy Rate Says No

One of the most ironic facts in the church today is that access to the Bible is the highest it’s ever been, yet so is biblical illiteracy. The average American (not just Christian) owns 4.4 Bibles. The number is even higher for Christians, and yet only 45 percent of those who regularly attend church read the Bible more than once a week, and almost 20 percent say they never read the Bible.[23] Despite owning several Bibles and having instant access to the Bible online and through smartphone apps, Christians don’t appear to be opening it up very often.

And it shows. According to a Barna study, only 19 percent of people who identify as “born again” Christians have a Christian worldview (defined as holding to some basic tenets of the historic Christian faith).[24] For instance, 46 percent of born-again adults believe in absolute moral truth. Only 40 percent of Christians think that Satan is a “real force.” Most shocking are the percentages of Christians who strongly reject a works-based approach to salvation. Even though salvation by grace through faith alone is a basic truth in the New Testament, only 47 percent of born-again Christians strongly reject the notion that it’s possible to work your way to heaven, and only 62 percent strongly believe that Jesus was sinless.[25] It’s no wonder that 68 percent of Christians believe that the famous dictum “God helps those who helps themselves” is a verse in a Bible.[26] It’s not. It actually comes close to a verse in the Qur’an.[27]

The lack of biblical literacy among Christians is again a discipleship problem. Don’t get me wrong. I don’t think we can reduce discipleship to a “worldview” curriculum. Discipleship is about transformation, not just transferring information. But there has to be at least some correlation between right thinking and right living. “Loving God with our mind” as Jesus commanded is certainly part of what it means to become “more like Jesus.” Discipleship is more than just learning, but it’s not less. Biblical illiteracy is a symptom of poor discipleship.

Where Do We Go from Here?

In the following pages, I’m going to interact with Barna’s The State of Discipleship study and other studies that have analyzed Christian discipleship in the United States. I won’t merely list a bunch of statistics, but I will examine the statistics and data to figure out what the church has been doing to disciple its people well and how the church can do a better job at making disciples who make disciples, who go on and —you guessed it —make disciples.

I will also interact with other relevant studies and authorities in addition to the Barna study:

- pastors and scholars who have been thinking and writing about discipleship;

- Christians and leaders who have thought through discipleship on a less public level;

- various books and studies on Millennials and the church; and

- personal friends, acquaintances, churchgoing Christians, and Christian “dropouts” whom I’ve met over the years.

My last source deserves some explanation. I’ve never been a full-time pastor, yet I’ve been heavily involved in church life as a deacon, elder, lay leader, teacher, or preacher in many different churches in my twenty-plus years as a Christian. I’m also a writer and a speaker, which means I get to visit and speak at many different churches around the United States (and the world). I’ve been exposed to the different ways in which Christians are “doing church” and discipling their people, which has been incredibly informative and eye-opening.

I used to think that not being a full-time pastor would disqualify me from writing a book on discipleship. But this way of thinking —that only pastors are qualified to talk about discipleship —is actually a big part of the problem. All Christians are disciples and disciplers. We all are missionaries and ministers who are called to serve God in his kingdom. But I’m getting ahead of myself. We’ll unpack all of this in the following pages.

So here’s a quick teaser of what’s to come.

Chapter 2 will talk about grace. If we don’t have a firm understanding of grace, our discipleship rocket will never get off the ground.

Chapter 3 shows why relationships are far more necessary than programs for discipleship. Programs aren’t bad. But programs without relationships have proven ineffective in helping people become more like Christ.

Chapter 4 makes the claim —and some will dispute this, but trust me, it’s biblical —that Christians can’t adequately become more like Christ on their own. We need other people. We need community.

Chapter 5 tries to blow the doors off church so that our faith can permeate our entire lives, not just our Sunday mornings. Christian discipleship should be holistic, not compartmentalized.

Chapter 6 argues that biblical literacy among Christians is a serious discipleship issue. People are dropping like flies from the church, partly because Christians appear to have their heads buried in the sand —ignoring the tough intellectual issues of the day.

Chapter 7 reveals that biblical discipleship includes mission, not just morality. You can be porn-free, drug-free, sex-free, alcohol-free, and never even watch movies on Netflix —and you could still be a terrible disciple. Morality is good. But without mission, it’s merely religion.

Chapter 8 exposes the fact that our churches are not very diverse, and this lack of diversity (in ethnicity, age, and socioeconomic status) is an unforeseen hindrance to discipleship.

Chapter 9 challenges the very structure of how we do church. Many churches (not all) have inherited a way of doing church that’s way too expensive and complicated. And this can be a massive roadblock on our journey of becoming more like the Son of God, who was born in a feeding trough.

The final chapter will talk through how to implement some of the changes I suggest in this book. Whether you’re a pastor, a lay leader, or a Christian who’s not in any formal leadership role, you’re called to be a disciple who makes disciples. We all must go. For some, the call to go will launch them overseas or across the border. For most, however, going will involve staying because the mission is all around us. We must all follow Jesus in the marketplace and in the streets, in our neighborhoods and at our schools, through our relationships with both Christians and non-Christians. We are all called to go —and make disciples who make disciples.

So let’s dive in and talk about that aggressive and scandalous and offensive thing called grace —God’s stubborn delight in his enemies.