5

ON EARTH AS IT IS IN HEAVEN

I WANT YOU TO MEET my friend Barry.[63] Barry is a Christian who owns a factory. He desires to have the gospel shape everything he does. Instead of maximizing profits at all costs, Barry believes that people come before profits. Even though he could maximize the company’s profits by paying his employees twelve dollars an hour, he pays them fifteen dollars instead. He doesn’t pay them more so that he can get them to produce more. Rather, he pays them more because, as image bearers of God, they are worth it.

Barry values people and family more than work. This is why he requires people to work seven hours a day instead of eight, and he gives every employee the third Friday off every month so they can spend time with their families or in the community.

Since Barry’s God doesn’t view people through a hierarchical lens, neither does he. So instead of structuring the factory’s pay scale based on hierarchy, he structures it based on need. Barry is the CEO, but he only has two kids. The janitor has six kids, one of whom is special needs and another who has an expensive medical condition. Instead of paying the janitor a typical janitor’s wage, Barry pays him more than he pays himself —since the janitor’s needs are much greater than Barry’s.

Barry also knows that immigrants and refugees have a hard time finding jobs, especially if they don’t know English very well. The patriotic side of Barry believes that “it’s every man for himself” and “if you’re going to come to my country, then you’d better learn the language.” But Barry’s Christian side wins out. Jesus commanded his followers to make disciples of all nations, and God is bringing the nations here. So Barry goes out of his way to provide jobs and English training for immigrants and refugees, believing that a multicultural community —even at a factory —best reflects the heart of God. Barry also recognizes that caring for the stranger and alien is a clear biblical theme, so he integrates this biblical theme into this vocation.

Question: how many hours a week does Barry put into his spiritual growth?

Some people would need more information. “How many hours does Barry spend in church on Sunday and Bible study on Tuesday? Is he in a Christian book club? Is he doing his devotions? Is he listening to Christian worship music on his way to work?” I would argue that much of Barry’s week is filled with spiritual growth because he’s integrating the gospel into every fiber of his vocation.

When your entire vocation is viewed as mission, there are very few hours that aren’t discipleship. There’s certainly a place for typical discipleship activities. But we’ve got to move beyond thinking of discipleship in terms of how many hours we spend doing church activities and engaging in spiritual alone time. Discipleship is a way of life —all of life.

Until we can explore how the gospel affects all areas of life, we won’t be cultivating holistic disciples.

Shattering the Sacred/Secular Divide

Many Christians function with a secular/sacred divide.[64] They consider discipleship to be an important part of the sacred aspects of life (attending church, going to Bible study, praying in the morning), but they don’t know how it relates to their so-called secular lives —their careers, hobbies, or forms of entertainment. Few Christians, it seems, view discipleship as a holistic endeavor, where we become like Christ in the way we think about art, beauty, economics, immigration, and science (among other things).

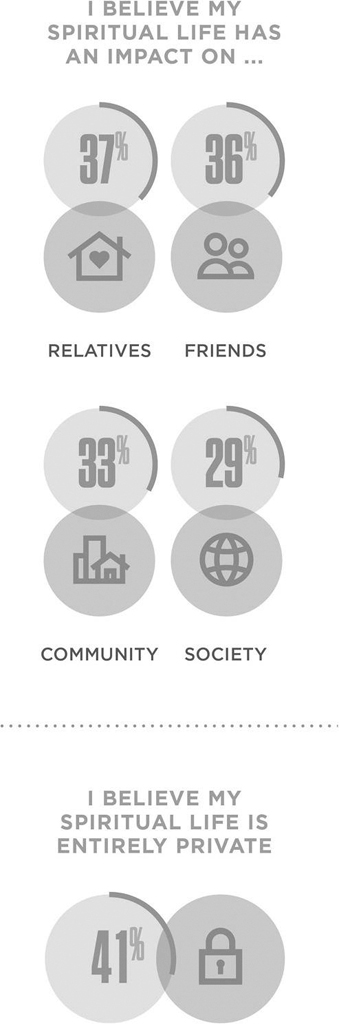

According to The State of Discipleship, most Christians view their “spiritual lives” as a private matter. The study reveals that 41 percent of Christians consider their spiritual lives to be “entirely private.” Only 37 percent consider their spiritual lives to have “an impact on relatives”; 36 percent say it has “an impact on friends”; 33 percent say it has “an impact on [their] community”; and 29 percent say it should have “an impact on society.”[65] While the previous chapter shows that many Christians would rather pursue Jesus by themselves, these stats show that many Christians think that their faith should impact only themselves.

Despite such compartmentalization, there’s a growing hunger to connect the gospel to all of life. While some Millennials still try to pursue Christ on their own, many of them desire to explore a more holistic gospel. Most people are passionate about their vocation, and the same is true for Millennials. The Barna study shows that 37 percent of Millennials expect to make an impact through their work within the first five years, and another 28 percent expect to do so in six or more years. Churches can nurture this passion and help Millennials stay connected to Christ by focusing on vocational calling outside of traditional church-based ministry. According to Barna: “Millennials who have remained active in their faith (45 percent) are three times more likely than church dropouts (17 percent) to say they learned to view their gifts and passions as part of God’s calling.”[66]

In other words, to help people stay connected to Jesus, churches should teach people how the gospel connects to all of life —especially their vocation.

David Kinnaman shows that most Christians still think that the gospel affects only their moral or spiritual lives; the bulk of their Monday-through-Saturday lives remain untouched by the Good News. Many Christians feel

that their vocation (or professional calling) is disconnected from their church experience. Their Christian background has not prepared them to live and work effectively in society. Their faith is “lost” from Monday through Friday. The Christianity they have learned does not meaningfully speak to the fields of fashion, finance, medicine, science, or media to which they are drawn.[67]

That second-to-last one is important: science. According to Kinnaman’s study, 52 percent of Christian teens in youth groups aspire to science-related careers, and yet only 1 percent of youth pastors addressed issues related to faith and science over the course of an entire year.[68] Part of the problem is that many churches tend to demonize the sciences for fear that Christians will lose their faith and become evolutionists. But the church should not be fearful of science; rather, it should learn how to thoughtfully engage the scientific world around it —a world that many of its members will be living in.

While we’re on the subject of faith and science, we might as well name the elephant in the room: The whole question of faith and science has become incredibly volatile and fear driven. This has caused many churches to either ignore the hard questions that people have or fail to create space for constructive dialogue and healthy disagreement. In my own experience as a Christian and theologian, I’ve seen many believers turn nonessential questions about the age of the earth or the interpretation of Genesis 1–2 into gospel truths. “If you disagree with a particular view, then you’re a heretic and can’t be a real Christian,” some say.

One’s interpretation of Genesis 1–2 does not have to be a gospel issue. In fact, I’ve met several people who resisted Christianity largely because they thought they had to hold to a particular view of the age of the earth. When they found out that genuine Christians disagree on this question and that they didn’t need to believe that the earth was only six thousand years old in order to worship Jesus, they got saved.

The point is, churches need to resist being controlled by fear-driven rhetoric and to explore ways in which they can nurture and train people to think critically about matters of faith and science. If the church doesn’t do it, the university will.

More and more people deeply desire to connect the gospel to all of life. They “want to follow Jesus in a way that connects with the world they inhabit, to partner with God outside the walls of the church, and to pursue Christianity without separating themselves form the world.”[69] In other words, they don’t want to maintain the secular/sacred divide, since all of life is sacred. Kinnaman points out that many of these people “are also creative types —artists, musicians, entertainers, and filmmakers —who feel their calling is out of tune with their Christian upbringing. They think the church doesn’t know what to do with creatives like them.”[70]

My friend Sean Michel is one of these creative types. Sean is a killer musician who hasn’t cut his hair or his beard in ten years. (Imagine: ZZ Top meets Phil Robertson without the duck call.) The dude absolutely shreds on the guitar and has a voice that makes Bono sound off-key. And Sean loves Jesus. He lives his life to glorify the name of Christ. But here’s the thing: Sean doesn’t play your typical kind of church music. There’s not much of a market in the Christian music industry for homeless-looking musicians playing ramped-up Southern Rock ten decibels too loud. So Sean plays at bars, clubs, and other venues that are filled with unbelievers. His lyrics are laced with aggressive theological themes that exalt Jesus’ name to the high heavens. Just look up “Sean Michel Hosea Blues” on YouTube, and you’ll find a gritty modern-day rendition of God’s grace written about in the book of Hosea, set to a heart-thumping beat that sounds like stuff you’d hear in a club.

Sean doesn’t believe in the secular/sacred divide. He believes that excellent music played in secular places can usher in the sacred presence of Christ.

Despite this growing desire to connect the gospel to all of life (especially vocation), church leaders still seem to be too narrowly focused on discipleship as church activities. When pastors were asked how many members are involved in discipleship, they said about 40 percent. Discipleship leaders were slightly more optimistic: 50 percent of church members, they say, are involved in a discipleship activity. But the way discipleship was measured was in terms of certain church activities such as attending Sunday school or fellowship group, meeting with a spiritual mentor, studying the Bible with a group, or reading and discussing a Christian book with a group.[71] When leaders were asked to estimate how much time their members spent “doing something to further their spiritual growth,” they said “about three hours per week.”[72] I fear that they might confront Sean for not taking his faith very seriously, since he’s out at some bar on Saturday night instead of attending Christian book club.

A Holistic Christian View of Vocation

When God created humanity, the first two commands he gave them were to “be fruitful and multiply” and to “have dominion over” the earth (Genesis 1:28). Or in urban lingo, “Have lots of sex and rule the world.” Not a bad gig, if you ask me. Anyway, that second command, to reign over the earth, is fundamental to our humanity. It has tremendous implications for our understating of vocation. When God put Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, he told them “to tend and watch over it” (Genesis 2:15, NLT) —in other words, to cultivate it, develop it, harness it, and expand it.[73] Adam and Eve’s work in the garden was a way of “reigning over” the earth.

The same is true for us. God put us on the earth so that we would mediate God’s rule over the world. God didn’t scrap his original plan when Adam sinned. He still wants us to apply God’s way of doing things to all areas of life, including our vocation.

I love how the end of the Bible picks up from the beginning. In Revelation 21–22, we see a new creation that looks a whole lot like Eden. There are rivers, vegetation, and human flourishing; there’s even a tree of life (Revelation 22:1-2). God’s plan to rule the world through humanity will be accomplished in the end. The meek will “inherit the earth,” Jesus says (Matthew 5:5). Or in the words of the heavenly choir: “You have made them a kingdom and priests to our God, and they shall reign on the earth” (Revelation 5:10, emphasis added). There will be quite a few hiccups between Genesis and Revelation, but the mandate remains the same. We all have vocations and callings in our lives, and God calls us to rule them well. The famed Dutch theologian Abraham Kuyper cried out, “There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry, Mine!”[74]

Jesus didn’t come preaching a gospel of individual salvation, nor did he come to take us to church. He came preaching “the kingdom of God” —the reign of God over all things. When Jesus announced the gospel of the kingdom (Matthew 4:23), he wasn’t just talking about the forgiveness of sins and going to heaven when we die. These things are included, of course. But his message of the kingdom can’t be limited to these things. Jesus’ kingdom message announced a new way of life, where the sick are healed, poor are fed, outcasts are included, and enemies and neighbors are loved. Jesus’ kingdom is a whole new reality, a different way of living, a countercultural existence that can’t be contained inside the four walls of a church building.

If you’re a Christian, you’re part of God’s kingdom. And you don’t leave this kingdom behind when you go to work. Remember Kuyper’s declaration: Every square inch —including your Monday-to-Friday routine —belongs to Jesus.

Integrating the Gospel into All of Life

So how do we do this? How can churches cultivate a broader, more holistic, view of discipleship?

Believe and teach a holistic gospel. It starts by actually believing that the sacred/secular divide is not what God intended. When pastors and leaders become passionate about connecting the gospel to all areas of life, this mindset will trickle down. If you want a great example of how to go about this, check out the lengthy sermon series connecting the gospel to vocation from John Mark Comer, teaching pastor of Bridgetown: A Jesus Church in Portland.[75]

Some will resist this message. There are Christians who are always scared when they hear something about Christianity that they hadn’t considered before. They equate “new” or “different” with liberal, sinful, and ungodly. I remember hearing a retired Bible professor tell a younger professor, “I’m getting nervous with all of this kingdom talk.” The younger professor had been teaching about Jesus’ holistic gospel, and he kept emphasizing the concept of kingdom more than (not instead of) the salvation of individuals. The younger professor was humble enough not to smugly remind the older professor that such “kingdom talk” is rooted in Jesus, who talked an awful lot about the kingdom. The older professor was so committed to winning individuals to Christ that he didn’t have the mental space to broaden (not change) his perspective, even if this “new” perspective came from Christ’s own preaching.

Some people will get nervous when you apply the gospel (and therefore discipleship) to all of life. But most Christians, especially Millennials, will appreciate it. As we saw from Kinnaman’s study, Millennials desire to understand the significance of their vocation. “Despite years of church-based experiences and countless hours of Bible-centered teaching, millions of next-generation Christians have no idea that their faith connects to their life’s work.”[76] In the absence of good, holistic discipling, the significance of their vocation has remained a mystery, an untested assumption. A holistic gospel gives them eyes to see the kingdom at work in the work they do.

Empower the outliers. Every church has outliers —people who don’t quite fit the mold. I’m not talking about unbelievers who try out church for a while but then leave because they don’t actually love Jesus. I’m talking about zealous Christians, passionate believers, people who would much rather feed the poor than listen to yet another sermon.

My cousin Paul is one of these outliers. From the time he was nineteen years old, he was a rebel, but he was also a Christian. He tried to attend a conservative Christian college, but they kept telling him to cut his hair so it wouldn’t touch his collar. (After three haircuts, he finally got it right.) He dropped out after a year, not because he didn’t love Jesus but because he didn’t fit into this Christian subculture. “I just couldn’t play that game. I wanted to spend my energy engaging in meaningful work.” He thought about becoming a pastor, but the thought of preparing and preaching sermons to Christians every Sunday seemed like a nightmare. He wasn’t really into “church” as it’s traditionally understood.

Paul ended up finding one of the most unreached countries in the world. I’d tell you the name of the country, but it could get him killed. He bought a plane ticket, and that’s where he’s spent the bulk of his life —pursuing a mission that 99 percent of Christians would never think of doing. He was run out of the country by terrorists a couple of years ago, but he’s now returned with his wife and two small children. He’s spreading the gospel in a gospel-less land by creating small businesses that provide jobs in an impoverished country. Jesus’ kingdom is breaking into this unreached country through the radical missional ventures of a wild-eyed outlier.

My friend Josh Stump is another outlier. He’s a pastor and church planter who has planted several churches in the Nashville area. Nashville is an interesting place. There are more churches in Nashville than delis in New York. It’s the Vatican of the Bible Belt. But the churches there are largely focused on reaching middle-class suburb dwellers. Josh’s heart is for the outcast, the marginalized, and the ones who would never set foot inside a megachurch, even if it has a great sound system. And Josh is the right guy to do it. Although he’s a pastor, he owns a cigar shop in east Nashville (the part of Nashville that you probably didn’t visit when you were touring the city). Selling (and smoking) cigars is his full-time job. If you entered his shop, you’d never know that he’s a pastor. He’s got more tattoos than Elvis had shoes, and his hipster beard puts David Crowder to shame.

“You know, Preston,” Josh told me, “I talk about Jesus and do more pastoring here in this cigar shop than I do at my church.”

“Your church sounds pretty Christless,” I gibed back.

Josh laughed with a lingering grin and kept going. “My customers don’t just come to smoke cigars. They come for relationships, community, and to talk about religion. Yet they would never go to a traditional church. And I fear that if they did go to a traditional church, they wouldn’t engage in the same depth of spiritual conversations that they do here in my shop.”

Boldly Following God into Our Neighborhoods

He’s right. As I sat there in his shop, coughing on a cigar, I kept seeing customer (friend) after customer (friend) wanting to engage in meaningful conversation with Josh. Religion, politics, sports, cigars, barbecue —they were all fair game. But it wasn’t long before Jesus came up in conversation. Josh’s Monday-through-Friday vocation is saturated with the presence of Jesus, whose glory shines through a smoke-filled room filled with misfits.

My friend Tasha was raised in a Christian home that was anything but Christlike. I’ll save you the details. Let’s just say that she was so spiritually abused that I’m surprised she’s still a Christian. Tasha’s not your typical churchgoer. She’s an outlier. She attends Sunday services, but beyond that she would score pretty low on the discipleship activity meter. She’s tried out various Bible studies and women’s groups, but they just don’t fit her. Maybe she should attend anyway, or maybe she should do something different. She’s always wrestling with her place in the church.

One day my wife was hanging out with Tasha in her neighborhood. As they were walking Tasha’s daughter to school, at least half a dozen women greeted her. “Hey, Tasha, thanks for bringing that meal last night!” “Tasha, thanks for praying with me yesterday.” “Hey Tasha, are we having our knitting group tonight?”

My wife was amazed. She had no idea. She never knew that Tasha had invested so much time and relational energy in the unbelievers in her neighborhood —people who would never set foot in a church. She’s been running that knitting group now for a couple years, and all of her friends who attend are unbelievers. “Some of them are starting to ask questions about religion!” Tasha said with childlike joy.

Tasha doesn’t fit the typical Christian subculture. She’d probably have a great time talking about Jesus at Josh’s cigar shop.

Every church has its outliers. They’re zealous for their faith, but they seek to live it out in unconventional ways. They’re often creative, energetic, and eager to reach the lost. They would rather be with unbelievers than with Christians, especially Christians who would judge them for not going to church more often. Many of these outliers end up leaving the church. They’re hungry to pursue God’s mission, yet they find that the church often stifles their passion.

A church that believes in holistic discipleship will empower its outliers. Rather than seeing them as a threat or a nuisance, holistic churches will value them and the unique call God has placed on them. Discipleship doesn’t come with some prepackaged formula that looks the same for all people. Rather, it meets people where they’re at and honors the diversity of God’s calling.

Some people are called to be pastors. Others are called to run cigar shops. Both are called to ministry. And it’s the church’s job to “equip the saints for the work of ministry” (Ephesians 4:12).

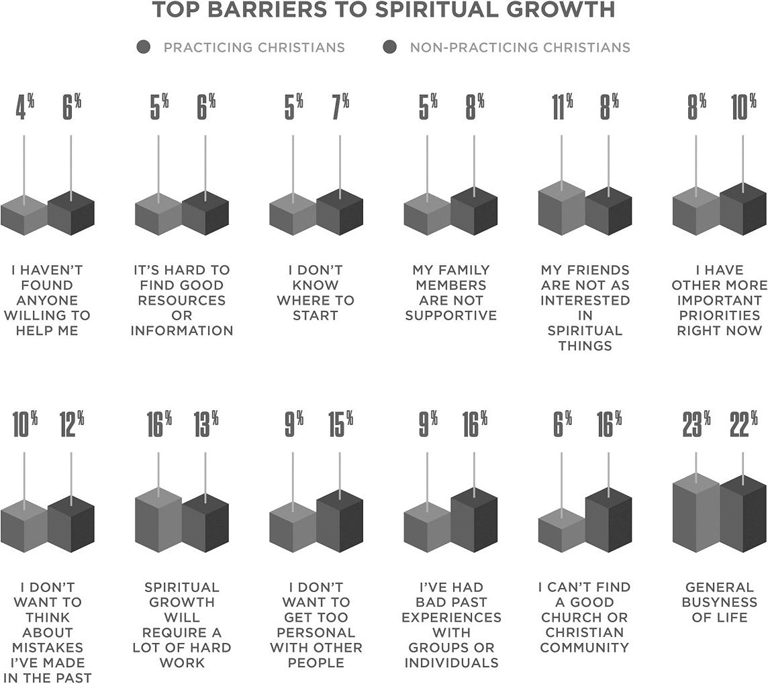

Asset-based discipleship. One of the biggest complaints among church leaders is that people are not engaged in discipleship. According to The State of Discipleship, pastors give various reasons why: “lack of commitment” (87 percent), “too much busyness in their lives” (85 percent), “sinful habits” (70 percent), and “pride that inhibits teachability” (70 percent) are the most common reasons church leaders give.[77] What’s interesting is that Christian adults don’t give the same reasons for their lack of participation in discipleship activities. For instance, while 85 percent of church leaders say that “busyness” is the main obstacle for discipleship, only 23 percent of Christian adults said the same.[78]

Could it be that church leaders only think that people aren’t participating because they’re too busy? Perhaps there are other reasons that leaders aren’t aware of.

Josh Packard and Ashleigh Hope addressed this very question in their book Church Refugees. Josh recalls talking to a pastor who complained, “People are just too busy to do anything. . . . They say they want things, but they don’t want to have to do any of it.” I love Josh’s response: “The sociologist in me has always bristled at these arguments.”[79] Josh suggests that maybe churches are creating programs, ministries, and discipleship activities from the top down, rather from the ground up. In other words, what the leaders think people need to be engaged in may not actually align with the diversity of callings that God has placed on the hearts of his people.

It’s the church’s job to harness and equip the gifts and passions of the body of Christ. But to do this, you have to begin by actually asking the body, “What do you want to do to make disciples of all nations?” Maybe it’s a neighborhood knitting group. Maybe it’s a laundry ministry to the homeless. Or maybe it’s sharing the love of Christ through art therapy. (One interviewee in Josh’s research helps people encounter the healing power of Christ through art.)

Josh talks about utilizing the principles of asset-based community development (ABCD) and applying it to the church’s discipleship.[80] Asset-based community development “focuses on identifying and leveraging the strengths that currently exist in a community rather than focusing on its deficits and problems.”[81] Instead of creating certain one-size-fits-all discipleship programs, an ABCD approach seeks to empower the unique gifts and passions of the people under your care. What if God has put in your congregation fifteen people who smoke cigars and have a fiery passion for the whiskey-drinking hipsters in your community? Telling them to join a Christian book club and then complaining that they’re “too busy” when they don’t show up isn’t going to help them become more like Christ.

Becoming Like Jesus —Holistically

Remember, Christ was dangerous and unpredictable. He didn’t play by the religious rules. He planted a church with hit men and treasonists at his side. He was so close to drunkards and gluttons that the religious elite thought he was one (Matthew 11:19). He wasn’t afraid to go to a party filled with scoundrels who didn’t have a moral bone in their bodies (Luke 5:29-32). If we are going to “become like Christ” in the way we disciple and are discipled, we may need to set aside our seminary notes and start from scratch —or start from the Bible. And then start with the passions and callings of the people. “The Dones,” as Josh Packard calls them, “demonstrated to us time and time again that they’re capable, talented, and driven.” He’s talking about their passion for the kingdom of God, their desire to touch a lost and dying world with the love of Christ. “They want the church to draw on their assets, not provide them with services.”[82]

A holistic approach to discipleship will break free from the shackles of “the way we’ve always done things” and explore new avenues to empower diverse people to live out God’s call to rule the world. The typical discipleship activities are important; we shouldn’t do away with church services and Bible studies. But we need to augment these forms of traditional Christianity with creative forms of empowerment, where diverse expressions of the Christian faith are not judged but enlisted into service for establishing God’s kingdom on earth as it is in heaven.