6

LOVING GOD WITH YOUR MIND

THE GOAL OF DISCIPLESHIP IS TRANSFORMATION. Discipleship is not just about gaining head-knowledge about God or the Bible, and it’s not just about getting people to attend more discipleship activities. It’s about Jesus —and helping people become more like him.

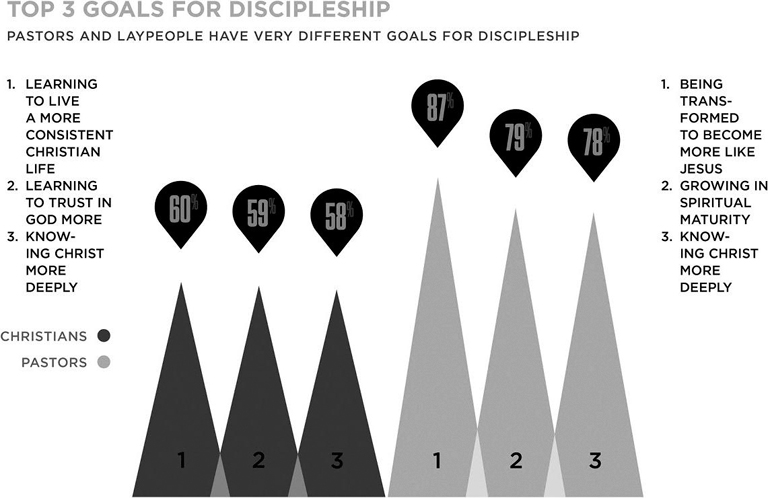

The State of Discipleship reveals that both church leaders and adult Christians agree with this sentiment. When asked about the goals of discipleship, most senior pastors said it was “being transformed to become more like Jesus” (87 percent), followed by “growing in spiritual maturity” (79 percent) and “knowing Christ more deeply” (78 percent). Adult Christians were a little less explicit, but they chose phrases that generally involved some sort of life transformation. The goal of discipleship is “learning to live a more consistent Christian life” (60 percent), “learning to trust in God more” (59 percent), and “knowing Christ more deeply” (58 percent). The Barna study concludes that “church leaders who embrace a culture of discipleship describe a shift away from ‘head knowledge’ toward life transformation . . . [and] leaders and Christians alike prefer the term ‘becoming more Christ-like’.”[83]

Every discipleship leader I’ve consulted agrees. It’s like a broken record. Discipleship is not just about learning or studying or attending a program. It’s about life transformation, learning to live like Jesus.

As the vice president of a Bible college, I often meet up with pastors to tell them about our school. Sometimes I feel like a salesman as I advertise our affordable tuition, relational environment, and commitment to the authority of Scripture. At this point, pastors are only somewhat impressed. After all, they’ve heard all of this before.

But it never fails. It happens every time. Pastors perk up and lean into the conversation whenever I talk about transformation: “At Eternity Bible College, we’re committed to reaching the heart, not just the mind. We have no desire to just fill our students with head knowledge. We teach in order to transform lives. If our students are not growing in love and humility and service toward one another, then they’re not truly learning.”

I usually just stop talking at that point because pastors love to continue the thought. After all, this is why they chose to go into the ministry. They want to see lives changed, not just minds filled. They want to see people transformed, not just informed.

But I fear that in an admirable effort to emphasize transformation, we may have swung the pendulum too far in the other direction. We may be neglecting a vital aspect of discipleship —being a learner and thinker. Discipleship is more than just learning and thinking. It’s about transformation. But to experience true transformation, we’ve got to pursue learning and thinking.

Disciple as Learner

The Greek word for disciple, mathetes, actually means “learner” in its earliest usage. The word first occurs in the work of fifth century BC Greek historian Herodotus, and after him Plato, Aristotle, Xenophon, and other classical writers use the term mathetes to refer to a student of music, astronomy, writing, hunting, wrestling, or other areas of study. The Sophists (an ancient philosophical school) used the term mathetes simply to mean “student.”[84]

In Jesus’ day, the word mathetes was used much more broadly to refer to anyone devoted to a significant leader or teacher. Jesus adopted this broader meaning as well. But notice that the aspect of learning is never left behind. Jesus didn’t do away with “learning.” He simply added “imitation” to it. After all, a significant portion of Jesus’ ministry —his discipleship —included teaching (Matthew 5–7; 10; 13; 18; 24–25). “Come to me, all who labor and are heavy laden,” Jesus said, “and learn from me” (Matthew 11:28-29). In one of the most significant statements he ever made about discipleship, Jesus mandated teaching disciples to do what he said:

Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you.

MATTHEW 28:19-20, EMPHASIS ADDED

You can’t be a disciple who makes disciples without some form of teaching.

I love what Paul says to the Ephesian believers. He addresses some sins that they should avoid, sins that unbelievers are engaging in (Ephesians 4:17-19). Then he says, “But that isn’t what you learned about Christ” (4:20, NLT, emphasis added). Paul’s challenge to avoid sin and pursue righteousness —transformation —is rooted in learning about Christ. He goes on to say, “Since you have heard about Jesus and have learned the truth that comes from him, throw off your old sinful nature and your former way of life” (4:21-22, emphasis added). For Paul, learning should lead to transformation, and transformation can’t be achieved without learning.

As in Ephesians 4, Paul cradles transformation with learning:

Don’t copy the behavior and customs of this world, but let God transform you into a new person by changing the way you think. Then you will learn to know God’s will for you, which is good and pleasing and perfect.

ROMANS 12:2, NLT, EMPHASIS ADDED

It’s not an either/or (thinking or transformation) for Paul. Divine transformation happens through “changing the way you think.”

The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind

In 1995, evangelical historian Mark Noll published his provocative and highly acclaimed book The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind.[85] The book won Christianity Today’s book-of-the-year award and has been hailed as one of the most important Christian books of its decade. After meticulously examining the evangelical tradition, Noll summed up his findings with his now-famous conclusion: “The scandal of the evangelical mind is that there is not much of an evangelical mind.”

Years later, Noll acknowledged that things have improved a bit —but only a bit.[86] Evangelicals are still plagued by an anti-intellectual spirit, and it shows. As we saw in chapter 1, the American church experiences an embarrassing level of biblical illiteracy despite having instant access to the Bible in several forms. It’s difficult to live out Christian values when you don’t know what those values are.

But the problem runs much deeper than just biblical illiteracy. Knowing the Bible’s content is important, but this doesn’t constitute the entirety of Christian learning. In order to “be transformed by the renewing of your mind,” we need to learn how to think, not just what to think.

All of the researchers who have studied both the “Dones” and the Millennial flight from church expose the same important truth: The church has done a poor job at thoughtfully engaging the pressing issues of the day. From science to sexuality, Christians are being told what to think, not how to think. Apologist Walter Martin used to say, “When we fail to give people good answers to their questions, we become another reason for them to disbelieve.”[87] The key word there is good. It’s not that Christians don’t give answers. The problem is that the answers are not always good ones, and Millennials in particular can sniff out a thoughtless answer a mile away.

At Eternity Bible College, one of our values is “education not indoctrination.” Indoctrination is when Christians are told to memorize the “right” answer, which means whatever the professor thinks is right. Instead, Eternity Bible College seeks to educate its students, training them how to think so that when they go out into the real world and don’t have a college professor at their side, they’ll be able to think critically and Christianly through all areas of life. It just so happens that a major complaint from the “Dones” is that the church doesn’t educate; it only indoctrinates. One “Done” named Emily said, “I’ve always had questions for the church, but there isn’t much room in Christian churches and denominations to question.” Another “Done” said that Christians in church “were only interested in my questions so they could answer them, and they thought they had all the answers.”[88]

Again, authenticity is a high value for most people, yet many churchgoers and former churchgoers don’t experience intellectual authenticity when it comes to difficult questions raised in church. Drew Dyck discovered the same complaint among people who have left the church. They “felt like Christians don’t have an appreciation for the nuances of reality. . . . Christians offer easy answers to complex questions.” Dyck gives his own honest evaluation to this complaint: “I don’t think Christian are simplistic thinkers. But I think that sometimes we feel the need to project an ironclad certitude when talking about our faith.”[89]

This ironclad certitude that leaves no room for discussion or disagreement is a common theme across David Kinnaman’s survey of Millennials. Of his six descriptions of why Christian Millennials are turned off by church, at least three are relevant here: Christianity is shallow, anti-science, and unwilling to wrestle with someone’s doubts. While Millennials are often accused of being lazy, selfish, immoral, or not wanting the truth (some of which accusations are certainly accurate), Kinnaman identifies a hunger in their souls that churches should be eager to feed:

This generation wants and needs truth, not spiritual soft-serve. According to our findings, churches too often provide lightweight teaching instead of rich knowledge that leads to wisdom. This is a generation hungry for substantive answers to life’s biggest questions, particularly in a time when there are untold ways to access information about what to do. What’s missing —and where the Christian community must come in —is addressing how and why.[90]

As a college professor, I wholeheartedly agree with Kinnaman. My students on the whole have deep questions about life, faith, sexuality, ethics, race, politics, immigration, justice, and a myriad of other topics that keep them up at night. And what makes my job so difficult is that they see right through thin answers to thick questions. Millennials are not like Gen-Xers and Boomers in this regard. When I was a college student back in the 1990s, I believed everything my professor said. After all, he’s the professor! He must know what he’s talking about. Boomers are even more hardwired to believe an older and wiser authority on any given topic. (Perhaps because they are usually the ones who are older and wiser . . .) But not so with Millennials. They have too much access to information and other “authorities” (including Wikipedia, unfortunately). They aren’t satisfied with memorizing the right answer. They’re wrestling with too many “right answers” floating around on the Internet. They want to know why and how and why not.

Translating Truths and Kingdom Ways

You know what’s gained the most credibility with my students over the years? Shockingly, it’s when I say, “I don’t know.” I used to fight against it. I thought that as the professor, I should always have all the answers all the time for all my students. But this became exhausting, especially since I only had some of the right answers to a few questions some of the time. Whenever I tried to cook up a “right answer” on the spot, they could see right through it. And they weren’t impressed. Over the years I built up the courage to say, “You know what? I don’t know the answer to your question. Why don’t we think through it together?” And my professor points went through the roof.

Jesus’ Teaching Method

Some of you may think that this is cowardly or unprofessional. Teachers need to give the answers, and students need to listen to them. And just to be clear, sometimes this is true. A professor who spends the majority of the class hour saying, “I don’t know” should probably be fired. There are times when I say, “This is what the Bible says, and if you’re a Christian, you’ll believe it.” But I still try to show them where, why, and how. After all, I don’t want them just to believe me. I want them to see where it says this in the text and to be able to navigate a thoughtful conversation with those who disagree.

But what’s fascinating is that even Jesus didn’t usually take a heavy-handed, monological approach. Sometimes he gave a lecture, where he didn’t take questions. The Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5–7) and his scathing rebuke of the Scribes and Pharisees (Matthew 23) come to mind. But most of his interactions with people were just that: interactions.

For instance, Jesus interacted on a conversational level with the woman at the well and led her in the ways of truth through dialogue (John 4:1-26). He did the same with the disciples when they returned from the city and wondered why he was talking with a Samaritan woman (John 4:27-38). When the crowds met Jesus on the shores of the sea, he invited them to explore the nature of the kingdom by giving them a series of parables (Matthew 13:1-35). When an educated teacher of the law wanted to know how to have eternal life, Jesus told him a story about a good Samaritan and then asked a question: “Which of these three, do you think, proved to be a neighbor to the man who fell among the robbers?” (Luke 10:36).

Much of Jesus’s teaching happened on a conversational level.[91] He stimulated people’s thinking with questions, stories, parables, and analogies, and he led them to the truth without spoon-feeding it to them. I love how Greg Ogden puts it:

Jesus allowed the disciples to live with conundrums. . . . No easy answers were provided, nor were there fill-in-the-blank workbooks. He wanted disciples who would have to think through the issues. Included in discipleship is the discipleship of the mind.[92]

Paul’s famous encounter with the philosophers on Mars Hill looked the same. Although he ended with a monologue and a plea to repent (Acts 17:22-31), he got this opportunity because he spent several days engaging with them in dialogical conversations:

He reasoned in the synagogue with the Jews and the devout persons, and in the marketplace every day with those who happened to be there. Some of the Epicurean and Stoic philosophers also conversed with him.

ACTS 17:17-18

Many of today’s discipleship methods are more monological than dialogical, and they don’t provoke good critical thinking. As Greg Ogden says, “Too much of the material that is produced under the heading of discipleship curriculum is spoon-fed pabulum. Jesus intentionally troubled the disciples by challenging their cherished assumptions.”[93]

Learning in the Early Church

The early church was devoted to learning. One could not say, “I want to be a Christian” and then say, “But I just want to love Jesus and not use my mind.” The two went hand in hand. When someone got saved during the early church period (AD 100–500), they were required to go through three years of intense study of the Bible and Christian theology.[94] I’m not talking about aspiring pastors or missionaries. I’m talking about all Christians. The early church didn’t think learning was an option. To be a Christian was to be a critical thinker.

And this has been true for most of Christian tradition. Until recently, Christians were always leading the way in the study of science, art, philosophy, literature, and various other subjects. Christians were the ones who invented the very concept of a university, where all subjects could be explored and mastered. The word university itself comes from two Latin words: uni and veritas, which mean “one truth.” In other words, there is one Christian truth that binds together and interprets all other truths in the world. Christianity has always been passionate about critical thinking. It’s never settled for memorizing certain doctrines and then just sticking our fingers in our ears and saying, “La la la la” to all of the hard questions the world throws our way.

The anti-intellectual, biblically illiterate, indoctrinating form of discipleship that plagues the church is stifling true, holistic spiritual growth.

Thoughtful Dialogue as Discipleship

The church needs to be a safe place to dialogue. We can’t be scared of hard questions, and we need to stop giving prepackaged, canned responses to complex issues. As we saw above, one of the biggest complaints about Christians, especially from younger people, is that we are too scared or ill-equipped to think through the tough questions of the day. We love to hear ourselves talk, and we keep regurgitating dogmatic answers to complex questions. We’re not known for thoughtfully and honestly engaging topics that matter. And many people are fleeing our churches because of it.

As I am writing this book, I’m also writing a series of blogs wrestling with a Christian theology of “intersex.”[95] Intersex persons are born with ambiguous genitalia, or a combination of both male and female biological characteristics. Some are even born with male XY chromosomes but female genitalia. Are they male? Female? Or some sort of sexual “other”? Are male and female the only two sexual categories, or do intersex persons show that there are other options? Did God make intersex persons this way? If marriage is between a man and woman, then whom should an intersex person marry? What if the doctor who “fixed” the deformity cut off the wrong part, and the female baby shows himself to actually be a boy later on in life?

How would you respond to these questions? Some would respond: “All humans are either male are female —period! La la la la la la.” But there’s a better response that appreciates the complexity of the questions, while revisiting God’s Word in humble dialogue with others doing the same.

There are many issues in life that require good, hard, honest, intelligent discussion. Should Christians fight against gun control? Is euthanasia always ethically wrong? How do we know that life begins at conception? Why are same-sex relations sin? Are they sin? Should we destroy our enemies or love them? Is ISIS our enemy?

Maybe there’s a “right answer” to all of these, but maybe there’s some gray area that will take some time to explore. Maybe we’ll go to the grave not having figured everything out, and that’s okay. The point is to engage the critical questions in life with honesty and Christian care and, above all, to not demonize people for asking hard questions.

As I was blogging about the intersex topic, the most common response I got from people was, “Thank you for taking the time to talk about this. I’ve been wrestling with this question for a while, yet no one in my church is wiling (or able) to talk about it.” Part of discipleship is helping people think through the critical issues of the day —helping them to be transformed by the renewal of their minds (Romans 12:2) and to “take every thought captive to obey Christ” (2 Corinthians 10:5). After all, Jesus commanded us to “love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with your mind” (Matthew 22:37, emphasis added). Loving God with our minds can’t happen if we leave our minds in the foyer as we walk into church.

Creating Safe Environments for Honest Dialogue

So how can we train Christians to think well as part of their discipleship? The most effective way I’ve found is to create safe and thoughtful environments for honest dialogue. In other words, we can’t rely on Sunday sermons to cultivate a biblical worldview among the people. There must be more.

Think about it. The fact is, most Sunday services are monological. They involve one person talking to many. Have you ever had questions about a sermon? Miscellaneous thoughts? Disagreements? Did you ever wish you could stop and ask for clarification or go deeper into a particular point?

I believe there’s a place for monological teaching. I don’t think we should do away with Sunday-morning sermons. However, younger people especially are growing up in a world of blogs and online news articles and interactive websites and YouTube videos. They can always ask questions or make comments. Personally, I find most of these comments quite annoying, and you probably do too. (If you don’t think they’re annoying, you might be the one commenting too much . . .) But annoying or not, that’s the world we live in. So it does feel a bit odd for many people to listen to a sermon and not have any space to dialogue about it.

Pastor and author Dan Kimball asked a bunch of people what they wished church was like. The response he got confirms my suspicion.

Virtually the first thing every single person I talked to said is that they wish church weren’t just a sermon but a discussion. They uniformly expressed that they do not want to only sit and listen to a preacher giving a lecture. And it’s not because they don’t want to learn. They expressed a strong desire to learn the teachings of Jesus and to learn about the Bible. Rather, they feel they can learn better if they can participate and ask questions.[96]

Some churches create such space by devoting post-sermon time for Q & A. Small churches are more conducive to live Q & A, but larger churches usually take questions via text. Other churches offer a postservice gathering that’s devoted to discussion. Now, this may not catch on. After all, many Christians are preprogrammed to come, listen, try to stay awake, and then rush home. But what would Jesus do? I think he would work hard to deprogram people, to wean them off of their religious routine. He’d challenge their assumptions and awaken their minds so they could learn to love God with heart and head.

Sunday-morning services may not be the best place for dialogue, or at least they shouldn’t be the only place. Genuine dialogue and interaction are best fostered in smaller settings. While one-on-one relations can be great for focused discussion and learning, I still think that a group of three to ten people can cultivate a healthy array of different perspectives and questions. I don’t mean this to be legalistic; there’s no magic number. But over the years I’ve seen more and more people shut down as the group gets larger. In my classes, about 20 percent of the students do 90 percent of the talking. In smaller groups, a much higher percentage of people will be more prone to interact.

You can also create other spaces outside the traditional Sunday service and midweek group. When it comes to learning and dialogue, the possibilities are endless. You could devote a special night (weekly, monthly, or bimonthly) to teaching and discussing hard topics. Or what about quarterly or yearly seminars or mini-conferences that are devoted to engaging with the ideas that everyone is already thinking about (politics, sex, money, terrorism, sex, race, sex, money)?

In Boise, where I live, I recently teamed up with a local pastor and another Christian leader to host what we call “City Forums.” These forums are monthly public dialogues on topics that live at the intersection of faith and culture. We want to talk publicly about stuff that everyone —not just the church —is talking about. An expert in a particular area gives a forty-five-minute talk, followed by another forty-five minutes of dialogue. (It often turns into a two-hour dialogue!) We just sort of drummed up the idea one day and decided to go for it. I planned to give the first talk on “homosexuality and the church,” since we wanted to start off with a nice, easy, noncontroversial subject. (What was I thinking?) We had no idea how it would go. As it turned out, more than one hundred people showed up. Most were Christians from about twenty different churches in the area. Others were non-Christians who heard about the event through the grapevine or through a Christian friend. Most were straight; some were gay. And everyone, I believe, felt safe to ask really hard questions and even disagree with the speaker —which wasn’t easy but was tremendously rewarding.

Notice that the City Forums aren’t just a free-for-all, where everyone could toss out their opinions and go home feeling good about their views. In order to honor the truth of God’s Word, we have an expert who has a biblical worldview address each topic. But in order to foster education rather than indoctrination, we created a safe space for people to ask questions and dialogue with the speaker and with each other.

Here’s the thing: the City Forums aren’t something separate from discipleship. Rather, the forums are one of many ways in which the church can help its people sharpen their thinking through learning, discussing, questioning, and being able to ask those hard questions that they’ve been so scared to bring up in church.

I don’t want to go too far down the rabbit hole of method. I’m not saying that every service must take text questions or that you, too, need to start your own City Forums. The point is that we need to think intentionally about how we can create safe places for people to ask hard questions and receive thoughtful answers. This is not icing on the cake of discipleship. It’s not an optional deluxe package to an otherwise fine-running car. It’s part of the engine itself.

Discipleship without learning is not biblical discipleship.