We were not allowed to swim in the ocean far below the Edgewater Hotel because we were on the rough side of the island. The “windward” side, Dad had called it. It was rugged and gusty, and the blue waves arrived in towering rows all the way from Africa. They glided across the ocean like a conquering navy and crashed against the shore, which was fortified with huge skull-shaped boulders crowned with spikes of sharp rock. The waves kept coming, but Barbados didn’t budge an inch. I figured if a wave ever hurled me against one of those prickly skulls I’d be gutted like the fish we had been eating for dinner each night.

There were small inlets of pink sandy beach as smooth and soft as slices of melon, but signs everywhere warned about the undertow. And we had been lectured by Dad

against going down the steps carved into the face of the coral rock to play on the beach. Just to make sure we wouldn’t get near the ocean, he told us the story of the two German girls. He gathered us on the wooden balcony overlooking the shore. The wind was briny with salt spray and blew our hair and clothes to one side, so that we looked like the small, twisted trees bent toward the land.

“Come here,” he hollered to the three of us. We huddled around him and watched his every move. He pulled up on the crease of his cream pants leg and lifted his brown shoe onto the lower rung of the balcony. I did the same. Pete did what I did. Betsy looked impatient and scratched a mosquito bite on her ankle.

He removed a cigarette from his case and tapped the filter against the face of his watch. Then, in one quick motion, he snapped open his lighter and shielded the flame with his free hand as he drew in a breath so deep his cheeks pressed against his teeth and bones like a mummy. Dad was warming up to telling a really good story.

“All Germans can read English,” he started, and raised a finger to mark his first point. “But the girls ignored the red warning signs and were swept out to sea by the undertow.” He pointed to the breakers, which slapped and fanned over the beach, then receded into the bottom of the following wave. “Still, they got a second chance. A Canadian father and son were on the shore and spotted them as they desperately waved their arms for help. ‘Stick with me,’ the father said to his son. They bravely dove into the water, but the son couldn’t keep up. They never reached the girls and the girls never reached the shore. The father was also dragged out to sea. Only the son was washed back onto

the beach. You can imagine just how that boy felt for not staying by his father’s side.”

I did imagine. He would have dropped to his knees on the shore and pounded his chest with his fists while the waves washed up over him. Somehow, I figured, the father was punished because the son was weak. I promised to do everything my father asked of me. Never again would I lie or cheat or misbehave. I’d be strong and brave and smart. I looked over at Pete. He had covered his eyes with one hand. I could tell he was thinking the same thing I was: Stick with Dad. Don’t let him down.

Dad continued. “A week later, what was left of the three bodies washed ashore on Crane Beach, some twelve miles away. The sharks had gotten to them first, then the crabs. You can just imagine how horrid they were,” he whispered and gazed dreamily out to sea. “They looked like bloated lepers.” He took a quick pull on his cigarette, then flicked it over the balcony. The wind blew it back against the cliff. He bowed his head in respect for the dead.

“I think they get the message,” Mom piped in just as I was forming a spongy, rotting picture of “bloated lepers” in my mind. She had crept up on us for the gruesome ending. I stared at the maroon paisley scarf she had fixed around her head to keep her hair in place. With the spooky mood I was in, each paisley design looked like a thick dollop of blood.

Dad snapped out of his daze and curled his arm around Mom’s waist. “We’ll be in the lounge if you need us,” he announced with a sudden new energy. The lesson was over.

“You all play by the pool,” Mom ordered. “Betsy, keep an eye on the boys. You know how they get.”

That was one of the differences between Dad and Mom. Dad could get us worked up to do anything he wanted by telling us a lesson story with a tragic ending. Mom just went right to the point and told us what to do. Even though she was pushier, he was more convincing.

Pete and I ran up to our room. We didn’t have to share it with Betsy, who was stuck with the baby. This meant we could wrestle and make all the noise we wanted and sneak out at night to raid the bar for bottles of lemon soda.

We had been living at the Edgewater Hotel for a week. Dad had flown down from Fort Lauderdale a month before us. When we joined him, our house wasn’t ready, so he checked us into the Edgewater because it was close to where he was fixing up a large private track club called the Round House. He took us to see it. It was the most beautiful building I had ever seen. It was pure white and sparkled with “diamond-dust plaster,” as Dad put it. The walls were round as a cake, and it had an orange tin roof as tall and pointy as a party hat. There was a little red flag in the shape of a horse sticking out the top. The driveway gravel was pink and reminded me of candy hearts. I picked up a piece and licked it. If it had tasted sweet it would prove we were living in a fairy tale. It tasted like clean dust and I spit it out. It really didn’t bother me that we weren’t living in a fairy tale. Living on Barbados was pretty close.

We threw our clothes off and pulled our new bathing trunks up over our skinny white legs. After we knotted the drawstrings inside our waistbands, we ran down to the pool. Betsy had settled on a lounge chair to read a book.

The baby was asleep in his carriage under a striped umbrella with fringe around the edges.

Pete and I gathered up a garden hose, a big rock, and my swim mask. We were playing a game we called “Deep-Sea Diver” after a movie we had seen in the television room. I was the diver and Pete was my air-pump and support crew. Anyone who dove into the pool would be a giant squid. If they touched me, I was strangled to death.

I put on my mask, stuck one end of the hose in my mouth, picked up the rock, and jumped into the deep end. I held my breath and sank to the bottom. I exhaled out of the corner of my mouth and watched the silver-and-blue bubbles go all the way up to the blurry surface. Then I breathed through the hose. It worked. There was air flowing through. I exhaled and took a deep breath. Then I held the hose with my right hand and tugged on it twice. That was the signal. In a moment I could taste lemon soda mixed with some funky inner-hose scum. Then there was more soda, and more. I needed to breathe. I pulled on the hose. The soda slowed to a trickle, then stopped.

This was great. I could have stayed there the entire day. Pete could feed me olives, raisins, and little Vienna sausages all washed down with my new favorite soda, Lemon Squash.

I was thinking that the air was getting a little thin and it would be a good idea if we had a bicycle pump to hook on to the hose so Pete could pump fresh air to me. Suddenly the hose was jerked out of my mouth and I swallowed a lungful of water. I pushed the rock to one side and sprang up toward the surface. “Why’d you do that?” I sputtered.

“Come quick,” Pete said and pranced up and down on his toes as if he had to pee. “Dad’s drowning.”

I dragged myself up over the stone edge of the pool and grabbed a towel as we ran toward the lounge. No one was inside. They were all out on the back balcony, peering down toward the rocks and rolling ocean and pointing at two tiny heads bobbing up and down over the huge swells. I could tell right away that with each passing wave they were drawn closer and closer to the prickly rocks. In a few minutes they’d be dead, pinned to the sharp spikes like prize butterflies. I also knew that neither of them was Dad. He wasn’t even in the water yet.

He was running across the beach. Without slowing, he pulled his shirt over his head, kicked off his shoes, unbuckled his trousers and hopped out of them, and waded into the water. He dove forward and began to swim. His arms and legs kicked up whitewater as he raced to reach the couple before they struck the rocks. It was going to be close.

“He’s going to die!” Betsy screamed. She was scared and angry. “Stop him! He’s insane!”

“He’ll be okay,” Mom said, and took a deep breath. She stood behind Betsy and held her shoulders. “He’s a good swimmer.”

He was. When we had lived on Cape Hatteras, he swam in the ocean all the time, right next to the signs warning everyone about the undertow. I was small then and thought undertow meant that if you stuck your toe into the water you got pulled under and drowned. It wasn’t quite like that. What it meant was that if you were swimming close to the shore a current of water could pull you straight out to sea and keep you from swimming back in. It didn’t

pull you under, but eventually you got tired and drowned. I knew there was only one way to beat an undertow. Once it carried you out to sea, you had to swim parallel to the shoreline for a while and then head in to the beach. That way, you swam beyond the control of the undertow current and lived to tell about it.

“He knows what he’s doing,” I said to Pete. “Watch him.”

Pete covered his eyes and peeked between his fingers. He still hadn’t learned to swim and was terrified of the water.

“He’s not even getting tired,” I said, elbowing Pete. “Keep your eyes open, you’ll learn something.”

Just then Betsy fell out of Mom’s grip and slumped to the floor. As soon as she landed on her rear, she hopped up and started screaming and swinging her arms.

“She’s hysterical,” said the bartender. “I’ll get her a brandy.” He ran off and returned with a golden drink and poured it down her throat. She spit most of it right out, but it worked. She stood on her own two feet and stopped struggling. Mom stroked her hair and quietly whispered in her ear. Someone brought a blanket and draped it over her shoulders.

Dad was still going strong. He swam up the swells, then down into the gullies, then up again, until he had almost reached them. And then he stopped. They were about twenty feet from the neck of an enormous rock with points as sharp as swords. All around its base was a circle of foam where the waves had surged up against it and angrily slid down.

He wanted to calm the couple before making his move.

He made a lot of hand gestures, then went forward with his plan. He swam up to the woman, turned her onto her back, and held her across the chest before she could struggle. Once he got her into position, he did a sidestroke and slowly angled down the beach and away from the undertow. The man followed. Stroke by stroke they pulled away from the rocks as the swells curled beneath them.

A group of men and women scurried down the steps to the beach, forming a human chain into the water.

“Can I go, too?” I asked Mom.

“No,” she replied. “You kids stay up here with me.” Dad had also told us all another true ocean story. Two children and their parents were on a small sailboat in a storm. The wife was hit by the swinging boom and knocked overboard. She went straight down into the dark water. The father tried to jump overboard to save her, but the children grabbed him and held him back. They could live with one missing parent, but not two. They would never know if the father could have saved the mother.

Mom didn’t want to lose more than one. But she wouldn’t have to. Dad had gone far enough downshore and had turned toward the beach. There was no undertow running against him. The waves carried him forward. The swells turned into breakers and they rode in as if on white horses. The chain of people grew longer and in a minute they had him. Then the woman. Then the man.

Two men dragged Dad ashore, where he sat slumped forward, with his head resting between his knees. Finally, once he got his breath back, he looked up at us and waved.

We waved back, wildly. I was so proud of him. He was

a hero. No one else risked his life to save that couple. Even if someone had, he would have drowned. But Dad was fearless. I knew I couldn’t have done what he did. But since he was my dad, it was almost the same thing. After all, I was named after him. I was a chip off the old block … If he could do it, I could do it.

A circle of men and women gathered around him and helped him to his feet. Then the entire procession climbed the steps and appeared up over the cliff. Betsy threw off her blanket and ran at him with her arms open. He picked her up and swung her over his head, then back to the floor, where she pressed her face into his chest.

Pete and I took a hand each as Mom kissed his face and smoothed his hair.

“Drinks for everyone,” Dad announced, his eyes flashing around the room. He was in good spirits. He pulled his hand from my grasp and swung around to point at the couple he saved. They were gone. Everyone fanned out to find them, but they had vanished. I stared out at the ocean to see if they had gone back in. Maybe they wanted to drown themselves like mysterious lovers who throw themselves off a cliff.

“Well, whoever they are,” Dad said with a quick laugh, “put it all on their bill.”

Everyone cheered.

By the end of the evening, the only thing we knew about the couple was that they were British, were on their honeymoon, and, as Dad put it, “were as dumb as dirt for swimming in water that could flip a battleship.”

In the morning, they had checked out.

Two days later we were sitting at dinner when the waiter brought Dad a cable. He ripped the envelope down the side and removed the message.

“Well, what do you know,” he said after a moment. “I saved some British royalty.”

“Let’s see,” Betsy said, squealing, and snatched the cable from his hand.

“Read it out loud,” said Mom.

“SORRY TO HAVE RUN OFF STOP COULDN’T HAVE PRESS INVOLVED STOP EVERY MEMBER OF OUR FAMILY THANKS YOU AND YOUR FAMILY STOP WHEN IN ENGLAND CONTACT LORD AND LADY JEFFRIES DUKE AND DUCHESS OF SUSSEX STOP 01-704-9776 ETERNALLY GRATEFUL.” She lowered the cable and sighed.

“Now, that is what I call a happy ending,” Dad said.

Mom didn’t think so. “I call it rude,” she pitched in. She was still annoyed because Dad had risked his life and they didn’t have the manners to say thank you to his face.

“Can we call the number?” Betsy asked.

“We’ll see,” Dad replied.

“I’d love to be British,” Betsy said, swooning. “They are so great. Every family has so much history to them. Like the Duke of Marlborough. Or the Viceroy of Firth. Or the Duchess of Windsor. And then there’s us. The Henry family. Now, that does not sound like greatness.”

“Wait a minute,” Dad cut in. “We’re Americans and we build great families the American way.”

Betsy raised her eyebrows. “And how might that be?”

“First,” he replied, “Americans don’t have royal families. We have business families, political dynasties, powerhouse sports families. Americans don’t have to be born into

greatness. We can make ourselves great. That’s the American way.”

Betsy smirked. “The American way is nothing but a rat race. I’d rather win the lottery and move to Europe.”

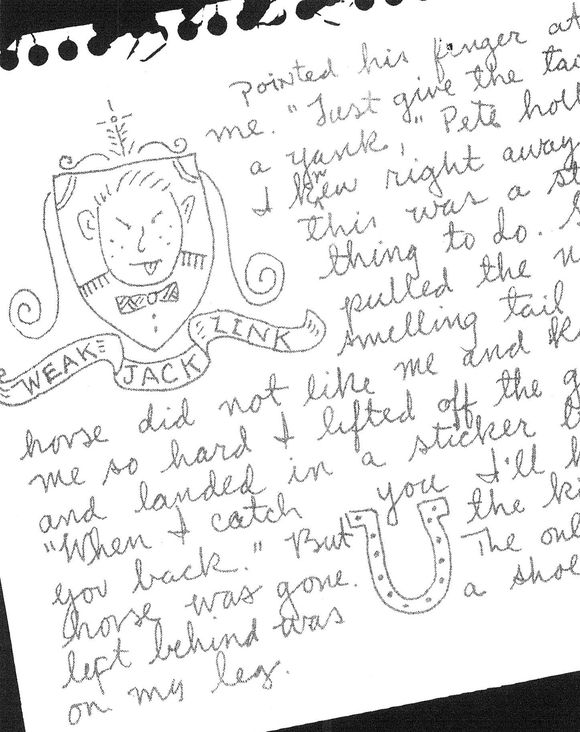

I was staying out of this discussion. Somehow I knew it would lead to something bad. I stared up at the dining-room walls. Just below the ceiling beams were a series of British coats of arms in the shape of little shields. On the shields were pictures of lions and eagles and fearless men in armor and words such as honour, courage, wisdom. The British used to own Barbados and had left a lot of their old stuff behind once the island gained independence. It would be neat, I thought, to have a Henry Family coat of arms.

Dad’s voice became louder. “All great families begin their road to greatness by facing their fears. So that’s how we’ll begin.” Suddenly he pointed his butter knife at my nose. “Jack, what’s your greatest fear?”

My mouth was filled with a huge chunk of bread. Mom, Betsy, and Pete turned to look at me. I couldn’t say a word. I just chewed and chewed. For a moment I thought my greatest fear was choking to death.

“Take your time,” Dad said warmly, giving me room. “Dig deep inside yourself and think of something that gives you the shivers, really makes you break out in a cold sweat and want to run away like a coward. Well? Come on. Time’s up. What’s it going to be?”

I swallowed hard. “’orses,” I managed to mutter.

“Huh? Speak up,” Dad insisted, leaning closer. “Don’t be so afraid that you can’t even say it.”

I took a quick sip of water and swallowed. “Horses,” I said. “I’m afraid of horses.”

Dad made a face. “Is that it?”

“Yeah,” I replied. “I’m afraid of being kicked by a horse.”

“Well, that’s a beginning,” he said. “Once you get over that, we’ll move on to something more important.”

He turned toward Pete. I sighed and thought of standing behind a horse and having it kick me on the forehead with a ten-pound steel shoe attached to its deadly back hoof. Just the thought of it made my shoulders flinch.

Pete had taken advantage of the two minutes it took me to ruin myself.

“Water,” he blurted out and started to twist his face up in a panic. “I can’t swim.”

“We’ll fix that,” Dad announced and waved his fork as though it were a magic wand. I half expected Pete to jump up, run across the dining room to the patio, dive into the pool, and swim like a dolphin.

“Betsy?” Dad said. “Let’s hear it.”

“Okay,” she replied. She had used the time to organize exactly what was on her mind. “I’m afraid I’ll call the number on this cable and they’ll ask me who I am, and who I know, and who were my ancestors, and I’ll tell them we are the Henry family and they’ll reply, ‘Henry? Are you servants? We don’t recall any Henry family.’ And they’ll hang up because we are a bunch of nobodies.”

There was a long pause while Dad leaned back in his chair. He gazed up at the ceiling and breathed deeply. Then more deeply. It seemed as though all the air in the room, the curtains, the tablecloth corners, the little table flowers, all nodded toward his flaring nostrils. After a moment, he exhaled and looked Betsy directly in the eyes.

“We are not a bunch of nobodies,” he said. “I know we’re

starting over here and we don’t have some long family history filled with snotty blue bloods. But that’s not what is important. We are a family at the beginning of greatness. All those British royalty had to come from somewhere. At some point they were living in caves, wearing animal skins, and beating each other with sticks. So, big deal, they’ve had a head start on us. Now they’re at the butt end of their empire and we are at the beginning of ours. And, for my money, I’d rather be part of something new and great than be some royal has-been.”

“Honey,” Mom whispered. “Keep your voice down. We don’t want to cause a scene.” There were a lot of British guests at the hotel.

Betsy lowered her head. She had taken it too far. There were times when she could beat him in an argument. But there were also times when he reared back and let her have it. He had just nailed her.

“So,” he said, wrapping up his point, “you can face your fear and give them a call.”

I felt like an idiot for revealing my fear of horses. A call would be easy to make. I should have said I had a fear of something like spending money. Then Dad could give me a bundle and let me face my fear by letting me go on a spending spree.

He turned toward Mom.

She put on a cheerful face and saved the mood of the dinner. “No doubt about it,” she said. “Driving a car is my greatest fear. And now with the baby I’ll be trapped if I don’t learn to drive.”

Dad nodded. “Very good,” he said with a jolly voice. “I’ll get you a car and lessons.”

“What about the baby?” I asked.

“He’s exempt until he’s three,” Dad replied. “Then he has to join the rat race like the rest of us.” He propped his elbows on the table and narrowed his eyes. “We’ll start tomorrow.”

But Betsy wasn’t finished. “What’s your fear?” she asked, still trying to corner him. “Everyone has something they’re afraid of. Even you!”

He tucked in his chin and stared out at us. “My fear,” he said, “is that you all will let me down.”

In the morning Dad came into our room. He woke Pete and me. “I’ve been thinking how to conquer fear,” he said. “It’s a combination of dread and encouragement.

“Jack,” he ordered, “you’ll help Pete build up his confidence today. Give him some easy lessons. Show him how you swim. All he needs is encouragement.”

“Okay,” I replied. I looked over at Pete and gave him our brothers-for-life wink.

“I’ll provide the dread,” Dad said, and sat down on the corner of the bed. “Listen to this. I knew a man once who was a great big guy. Huge. Big arms, big legs. All muscle and not afraid of a thing. But his son was afraid of the water. Couldn’t get near the stuff without shaking all over like a girl. The father tried everything to teach the boy about the water. YMCA swim lessons. Swim camp. The whole thing. Finally he got frustrated. He picked up the boy and put him in a speedboat and roared off into the harbor. He pulled up to a buoy and set the boy on the little floating platform. ‘You’ll either swim in or you’ll starve to

death out here,’ he growled, and roared off. And you know what?”

Dad paused.

“He starved,” whispered Pete, with his face all white and his hand over his eyes as he imagined the boy on the buoy.

Dad grabbed Pete by the head and gave him an Indian rub with his unshaven chin. Then he let him loose. “No, knucklehead. The boy swam to shore. He could swim all along. He was just being stubborn!”

“But I’m afraid,” Pete said.

Dad had reached his limit. He stood up. “Jack will help you swim. Just as you’ll help him with his fear of horses.” Then he left.

Pete dropped onto the floor and peeked up at me like a kitten about to be drowned.

“I’ll help you,” I said. “We can’t let him down.”

“And I’ll help you with the horses,” he replied. “I’m not so scared of them.”

After breakfast I wanted to get started but Pete refused.

“You can’t swim on a full stomach,” he said. “Let’s do the horses first.”

He was right. “Okay. But let’s just get it over with.”

Horseback riding was advertised in the hotel brochure. There were stables and long horse trails cut through the brush and trees on the land side of the hotel.

We had started down the footpath to the stables when Pete said, “Stop, I have to tell you a story of dread before I give you encouragement.”

“I have enough dread,” I said, groaning.

“We have to play by the rules.” Pete sat down on the path. “I won’t help unless you listen.”

I sat next to him.

“Once there was a boy named Alexander. His father owned a huge horse and everyone who tried to ride it was thrown off and killed. Alexander’s father said that if anyone could tame the horse they could have it. Everyone who had tried to ride the horse faced it toward the sun. So Alexander faced the horse away from the sun. Then he jumped on the horse and rode away. When his father saw what he had done, he gave him the horse and called him Alexander the Great.”

I glared at Pete. “You’re scaring me because I can’t figure out what you mean,” I said. “Where’s the dread?”

“I mean that if you use your brains you can win. Horses aren’t very smart.”

“They don’t need brains,” I said. “They’re killers.”

We walked down to the stable. A short, heavy man named Mr. Doobie cared for the horses. I figured he was an old jockey who’d retired to eating.

“I got a nice one,” he muttered, and pointed to a dark, nervous giant. Its eyes were like polished stones. “He used to be a racehorse at the track down below until his accident.” He pointed at a two-foot jagged scar running down the animal’s neck. “He can be a little moody if he don’t sleep well. He still has nightmares of that picket fence.”

I hoped he’d had a good night’s sleep. His name was Winny and he was wearing a Western saddle, which I liked because it would give me something to hang on to. Still, as soon as I got close to Winny my fear of him made

me weak. When he shuddered and waved his big head from side to side and snorted, I jumped back a few steps. His hind leg twitched and I was sure he wanted to kick me into the water trough.

Pete wasn’t impressed. “Horses know when you are afraid of them. Just treat ’em like big dogs.”

Finally, he had said something dreadful. I also had a huge fear of big dogs.

“Are you afraid of riding horses?” Pete asked.

“I’m more afraid of being kicked in the head,” I said.

“Then let’s conquer your greatest fear, like Dad said. If you get over being kicked, then riding them will be a breeze.” He took the bridle and walked the horse down the path and away from the sun. I waited until he had gone about twenty feet before I followed. When he stopped, I stopped.

“Come here,” Pete said. He pulled his T-shirt up over his head. “Tie this around your eyes.”

I did.

“Give me your hand.”

I held it out. He clutched it and pulled me along. I hadn’t covered my ears very well and heard the horse pawing the ground and shuddering.

“Now stand here,” he said.

I stood as stiff as a pillar. With each breath I smelled the horse and figured it smelled my fear. I felt the ground move as it tramped up and down. I could sense it was lining me up for a world-class kick. I gritted my teeth and waited for the blow.

“Reach your left hand straight out,” Pete ordered.

I did. I touched the horse and instinctively pulled back.

“Just do what I say and you’ll be fine. Now stick out your hand.”

I extended it, slowly. I felt horsehair and the roundness of his rump. I lifted my hand just so it hovered over the horse. I didn’t want to disturb it.

“Move your hand down until you feel the tail,” Pete ordered.

Slowly, I lowered my hand until I felt the long, coarse hairs.

“Now gently grab the tail.”

I did.

“Now give it a little tug.”

I froze.

“Just a little tug,” he insisted. “Then you won’t have to do any more and I’ll tell Dad you conquered your fear.”

I took a deep breath and yanked the tail as though I were pulling a bell rope. The horse kicked me so viciously in the thigh that I skipped across the ground, staggered up the dirt path, and collapsed sideways into the bushes. The horse galloped off as I reached up with my free arm and jerked the shirt over my head.

Pete was laughing so hard he had dropped onto his knees. When he saw me staring at him, he stood up and backed away.

“I’ll kill you! I’ll murder you!” I shouted. “No, I won’t murder you. I’ll drown you! I’ll make you go deep-sea diving without a hose. You’ll do more than face your fear. You’ll face your Maker!”

“I was just trying to help,” he cried. “You faced your fear and you survived. It wasn’t that bad.”

I may have survived, but my fear had multiplied. I

untangled myself from the bush and put all my weight on my leg. It held. It wasn’t broken, but it throbbed. I undid my belt and dropped my pants. There was a red horseshoe-shaped bruise glowing on my swollen thigh. I could even see where the nail heads had made little circles on my skin. The horse had branded me. It owned me. I pulled my pants up.

“You’re dead,” I said, and began to limp up the path. “Just return the horse to the stable before I drown you.”

I needed to lie down.

Pete didn’t wait for me to drown him. After I rested my leg, I put on my bathing suit and went down to the pool. He was in the shallow end with a Styrofoam bubble strapped to his back and little plastic water wings on his arms. He couldn’t sink if I sat on him.

“Hey,” I said. “You’re doing great.”

He turned and smiled up at me. “Thanks,” he sputtered and thrashed his arms around. “I was so afraid you’d drown me I started without you.”

Dad was right. Fear of one thing can really get a person to face the fear of another thing altogether.

I stepped into the water and waded over to him. “Okay,” I instructed. “I’ll hold you up as you swim from side to side. But first you have to take off the water wings.”

“I keep the bubble on,” he insisted.

“Okay.”

“Sorry about the horse,” he said. “I was just doing my best.”

“You’ll notice,” I said, “that I am not asking you to practice in the deep end. What you did to me was like pushing a

blind man into traffic so he could get over his fear of cars. Now let’s go.”

I held him under the belly as he began to swim the crawl with his legs kicking and his arms flailing. Then I unsnapped the clip on his bubble and stepped away.

“Excuse me,” I shouted above his splashing. “I forgot to tell you a story of dread. Once upon a time there was a demented older brother with a horseshoe branded on his leg …”

He finally noticed he was alone. “Help,” he gurgled.

“You need help holding your breath?” I asked, and pushed him under. I counted to three, then hauled him up.

“Help!”

“Who is the boss?” I asked.

“You are.”

“Who is the master?”

“You are.”

I led him over to the edge. “Tomorrow I’ll teach you the fine points of swimming,” I said.

He grabbed the edge of the pool and held on. Now he had plenty of dread.

When we sat down to dinner, everyone seemed to be smiling except for me.

“Well,” Dad started. “I didn’t tell you this last night. I didn’t want to jinx myself by talking about it. But I was afraid that my bid on a hotel renovation might not be accepted. I thought I had bid too high. And without that job I would have let all of you down. But I found out this morning that the bid was accepted, and I’ll be working

close to where we’ll be living on the other side of the island. The job is good for at least half a year.”

Mom leaned over and gave him a kiss. “Congratulations, honey,” she said. He beamed.

Pete was next. “I did some swimming,” he blurted out.

“Good work, son,” Dad replied. “I knew I wouldn’t have to drop you off on a buoy.”

“And I did some driving,” Mom chirped, and nodded approvingly at herself.

“But you’ve always been terrified of driving,” I said. I was really counting on her not to face her fear. “And the drivers here are insane.”

“I know. But your dad told me a little story that really hit home.”

“What’s that?” I asked.

Mom glanced at Dad.

“You tell him,” Dad replied and nodded.

“It was back in Fort Lauderdale. There was a woman who had a baby that was choking on a leaf. She couldn’t unblock the baby’s throat. There was a second car in the garage but she didn’t know how to drive. She called the fire department but they couldn’t get there right away. The hospital was only about ten blocks down the road and so in a panic she grabbed the baby and began to run. But the baby died in her arms just as she reached the emergency-room doors. If she had known how to drive, she would have saved that baby’s life. When your dad reminded me of that story, I knew I couldn’t let something like that happen to any of you kids, so I got in one of the staff cars with

the chef and we practiced driving in a straight line up and down the service road.”

“Very impressive,” Betsy said and clapped politely. “And, believe it or not, even I have something to report.”

“What?” I spit out. “What?” I could feel the world slowly closing in on me and my horse fear. I was going to be the only loser.

“Before I tell you, I want to apologize to Dad for talking the way I did last night. I was wrong to be so critical of us all.”

What was wrong with her? She must have been turned into a zombie overnight. She never apologized for anything in her life. Never!

“It happens to the best of ’em,” Dad said with a chuckle. “Now, what’s your news.”

“Well, after that little story you told me,” she said, nodding toward Dad, “I faced my fear. I called the British couple you saved and told them who I was. And they were really nice. They said you were a hero and they’d told all their close friends about this great American man who saved them and they apologized over and over for not thanking you in person but they weren’t supposed to be on Barbados since they told their snoopy families that they were going to Italy because they wanted some privacy from the hundreds of royal relatives that would want to join them on their honeymoon.”

“See,” Dad said proudly. “If you hadn’t called, you wouldn’t have known the truth of the matter.”

“What story did you tell Betsy to get her going?” I asked.

Dad smiled at Betsy. She turned toward me. “Dad told

me about his older sister who had a big crush on a man named Harvey Jacobs from the rich side of town. She never told him she liked him, because she was from the poor side of the tracks. She ended up marrying someone she didn’t like as much. After the wedding, her new husband said to her, Boy, I feel lucky to be married to you because Harvey Jacobs has been in love with you forever. So if she had had the courage to call Harvey Jacobs and tell him how she felt, she would be with her true love and not with some yokel she settled for. The lesson is, if you don’t have the guts to ask, you’ll never find out what people think of you.”

I’ll never have to read another book for the rest of my life, I thought. I just have to hang around Dad all day and I’ll hear a story on every subject known to man. But where was mine, I wondered. What could he possibly tell me that would get me over my horse fear?

Then very slowly I could feel everyone turning their eyes on me.

“Jack, do you have anything to tell us about your day?” Dad asked.

I looked at Pete. He was sucking on a lime wedge. He had a story to tell, but he kept it to himself.

“Can I talk to you about this later?” I asked. “I’m not feeling well.”

“Certainly,” Mom said.

I pushed my chair back and limped out of there as quickly as I could. I went to my room and sat on my bed. I imagined our coat of arms, which would be passed down to future generations. There will be a picture of Mom driving a car. Under the picture will be the word Bravery. Dad will

be painted standing on top of a pile of money that spells out the word Success. Betsy will be wearing a little royal crown and under the picture will be Courage. Pete will be pictured leaping off a high diving board above the word Fearless. Then there will be me. I’ll be shown being trampled by a horse above the words Weak Link.

I stood up and looked into the mirror. I wanted to scare myself. “Weak link,” I jeered at my reflection. “Weak link.” After a moment my reflection whined back. “I can live with that.”

Just then Dad came into the room.

“After you left the table Pete told us he tried to give you some encouragement. Said it didn’t work.”

“It backfired,” I said.

“Well, I could tell you a story that would point out how facing your horse fears would make you a better man. But instead of making up a story, I’d just rather tell you the truth.”

He sat down and draped his arm across my shoulders. I had a feeling that the truth was going to be scarier than a story.

“Simply put,” he stated, “you can’t fail. I won’t allow it. You are named after me. If you fail, it’s like me failing. If I hadn’t saved that couple, I wouldn’t be able to look you in the eyes. If you can’t ride that horse, you won’t be able to look me in the eyes. And a son that can’t look his father in the eyes is a coward. And if we can’t look each other in the eyes we will go through life like strangers.”

“I’ll try my best,” I said.

“I’ve got great faith that there will be a happy ending to

this story,” he said. “If you get weak-kneed, just think of me diving into that ocean. It takes courage to be a man.” He slapped me on my swollen thigh, stood up, and left the room.

When I woke up the next morning I didn’t even open my eyes. I could hear the wind and rain beating against the windows. It was a day to avoid horses. It was a day to avoid Dad’s eyes. It was a day to avoid mirrors.

I opened my bedside drawer and pulled out my diary. I held it up to the key around my neck and unlocked it. One of the big differences between me and Dad was that he talked all his stories out. I wrote mine down. But since arriving in Barbados I hadn’t written a word.

This was a good day to get caught up. I started with the story of the German girls drowning. Then I wrote about Dad being a hero. I wrote down everyone’s fears. Then I wrote Dad’s stories about the boy on the buoy, the choking baby, and the woman who settled for the wrong man.

But there was one story that wasn’t his. It was mine. I wrote the first half of my horse story. The ending would have to wait until I had lived it.

Suddenly I was starved. I had skipped breakfast but was ready for lunch. I went down to the dining room. Pete was eating a club sandwich and French fries. I sat next to him and picked off his plate.

“Once upon a time,” he started, “there was a boy who tried to eat an apple in front of a horse. But it was the horse’s apple. So, when the boy wasn’t looking, the horse bit off his hand.” He dropped his sandwich and tried to bite

me on the wrist. I yanked my arm back and smacked him hard with a straight right to his shoulder. It knocked him off his chair.

“I’m just trying to help,” he hollered from the floor.

“You’re driving me nuts,” I yelled back. I grabbed a handful of fries and ran to the back of the hotel to be by myself.

The rain had stopped, so I went down to the stable and asked Mr. Doobie to saddle up Winny.

“I think he’s in a good mood today,” he speculated.

“How do you know?”

“He always liked a sloppy track.”

“Oh.” I had zero understanding of what horses liked or disliked.

While Mr. Doobie strapped the saddle on Winny, I worked on my story. Once upon a time there was a boy who was so afraid of horses that he wouldn’t go near them. His father insisted that he try. And so one day he did. But …

“All set?” Mr. Doobie asked.

I just stood there. I wasn’t certain what to do. But I had to do something. My story needed an ending.

“I saw where Winny gave you a kick yesterday,” he said.

He was neither sympathetic nor critical, but I was embarrassed that he knew. I must have looked foolish to him.

“I once saw a jockey get kicked in the head. He had bent over to pick up a riding crop. Killed him instantly. Fell over like a three-legged chair.”

“Well, it only grazed me,” I replied. “It was just a game I was playing with my brother.”

“Dangerous game,” he remarked sharply. “I wouldn’t do it again. Kinda like playing with a gun. There is no need to shoot yourself to see if it will work.” He reached into his pocket, pulled out a small brown bottle, and took a swig. I hoped he didn’t share that stuff with the horse.

I had heard enough stories and bits and pieces of happy and sad endings. Nothing anyone said was going to change how I felt. I had to face this fear myself.

I walked up to the horse and put one foot in the stirrup and swung my other leg up over the saddle.

The horse started to walk sideways like a crab, then forward. I grabbed the saddle horn with both hands and dropped the reins. I thought that letting go of the reins would be like putting on the brakes. It was more like pressing on the gas.

“Just hang on,” Mr. Doobie shouted as I pulled away. “He’ll do the rest.”

Winny took off in a trot. I held on as I bounced up and down. I leaned forward with my chest on the back of his neck and grabbed the reins. “Whoa, boy. Whoa.” I yanked them back.

He didn’t listen. The saddle smacked my rear end with a jolt that ran up my spine and rattled my teeth. I stood up in the stirrups and pressed my knees together. Winny continued to trot.

After a few minutes I got into the clip-clop rhythm, but I couldn’t stop Winny and I couldn’t steer him left or right. He had his own destination in mind and I just hung on. But as long as I was on top of him, he couldn’t kick me.

The road turned and went down between two small hills. As soon as I saw the point of the orange roof with the

horse flag on top I knew where Winny was heading. He was going back to the track behind the Round House to face his fear of picket fences.

The road curled to the left and we started up the driveway. The pink gravel crunched under his hoofs.

Dad was examining a set of blueprints on a plywood table when he heard me. He looked up and waved. I smiled and pulled back on the reins. To my surprise, Winny came to a stop.

“Need some help?” he called out.

“No,” I said. “He’s just getting used to me.” I threw my right leg up over the saddle and hopped down like a seasoned cowboy.

Dad was standing on the other side of the horse. I could walk either in front of Winny or behind him. There was no choice. I had to go for complete victory. If Dad was going to use me for one of his lesson stories I had to give him a dramatic finish. I could imagine him telling a friend the story of my short life. “And then the boy walked behind the horse to embrace his father, but before he could reach him, the horse reared back and kicked and the boy’s head exploded as if he had walked into a spinning propeller.”

“A tragedy,” the friend would reply.

But I lived to give him a happy ending. I walked right behind Winny and slapped him hard on his rear. He took off like a rabbit. I stuck out my hand. “Shake,” I said to Dad, and looked him directly in the eyes.

“You bet,” he said happily, and clasped my hand with his.