I had just returned from Bayley Clinic when Betsy heard me sneaking down the hall. She whipped open her bedroom door and pointed her finger directly at my swollen, purple nose.

“Don’t take another step toward me,” she said as she shook her head in disgust. “It’s bad enough that we’re new on this street, but having a purple brother is only going to make people avoid us even more. Please,” she begged. “Don’t go outside. Just give me a chance to make friends before the neighbors find out I’m related to a purple freak.”

“It’s not my fault,” I replied. “It’s medicine.”

“You brought this on yourself,” she snapped. “I told you that disgusting chicken-chasing game was going to make you sick. Before long, you’ll be crowing at the sunrise and pecking the ground.”

“It wasn’t the chickens,” I protested. “You don’t know everything.”

“Then what?” she shot back. “What?”

“It was the wart.”

“The only wart you have is throbbing inside your skull,” she said sarcastically.

“Well, I bet I make a new friend here before you do,” I yelled and lunged at her.

She cringed. “You’ll never make a friend. You’re a freak of nature.”

Pete came around the corner and held his nose. I smelled like vinegar. I crossed him off my buddy list. “Pete doesn’t count as a new friend,” I said, setting the rules. “He’s just a pest.”

“You’re on, wart boy,” Betsy replied. “But I warn you. If you come snooping around when I’m trying to make friends, I’ll call the center for disease control and have you quarantined.”

She probably could, I looked so bad. But I was telling the truth about the wart and she knew it. The wart was just the start of my disease. Now I had Day-Glo purple circles painted on my arms and legs. My belly was purple. My face, my ears, my neck, and even where people couldn’t see me, I was purple. I had broken out in little pink blisters and boils and the nurse had painted me with Gentian Violet, which was so bright Pete put on his sunglasses to look at me.

“I am not a freak,” I declared. “Mom!” I shouted.

“He’s not a freak,” Mom said matter-of-factly and scooted past me. I thought she could have put her arm around me and given me a motherly hug instead of treating

me like a mutant. But she was wearing a white dress, and I was still a bit sticky. “He’s sick,” Mom said and placed her hand over her heart. “You should be thankful that it is just blood poisoning and not leukemia. Now leave him alone.”

“With pleasure,” Betsy said and marched into the kitchen.

I retreated to my room and closed the door. I hated being purple. It was the most embarrassing thing that had ever happened to me. I knew I was supposed to feel thankful that I didn’t have leukemia, but when I examined myself in the mirror, I was horrified. Betsy was right. I would never make new friends. Who would want to play with a purple kid? I took off my T-shirt and shorts. I opened my closet and took out a long-sleeved shirt and jeans. I put them on and pulled a Pittsburgh Pirates cap down over my head. I glanced into the mirror again. I looked like a well-dressed grape. I wished I had a ski mask to cover my face. I took out my diary and began to write down what was happening to me. It was all pretty weird.

My purple trouble had started five days before, when our housekeeper, Marlene, taught us how to play “Chase the Chicken.” She called Pete and me into the back yard and stood us next to a tree stump. In one hand she held a chicken upside down by its feet. In the other hand she gripped a machete that was so shiny under the hot sun it made me squint. “Your mother wishes chicken for supper,” she said. On a tree branch just behind her head, a second chicken hung upside down from a twine handle tied around its feet. It clucked.

“Are you lads ready?” Marlene asked. She sounded like the Queen of England.

“Ready for what?” I asked.

“To give chase to the headless chicken,” she replied. “It’s a game all children play here.”

I glanced at Pete and shrugged my shoulders. I wanted to fit in. I didn’t want to be the weird boy who wouldn’t chase a chicken.

“Sure,” Pete said.

“Whichever one of you catches the chicken gets to eat the heart,” she explained. “I’ll fry it up in a special Bajan sauce just for you.”

“Okay,” I replied, thinking that we could never have played this game in Florida. Nobody killed their own chickens in Florida. People just went to the supermarket and bought those pre-killed chickens that looked as if they’re made out of yellow rubber. And butchers hide the heart and innards in a little pouch tucked up their butt. Who would want to eat something that was stored there?

“Then get ready,” Marlene ordered.

“Ready,” I replied.

“Me, too,” said Pete.

She held the chicken down with one strong black hand and raised the machete up over her head with the other. The wind picked up and her wide orange dress snapped around her like a mad flame. She looked at us. “On your mark,” she hollered. We squatted down into a sprinter’s pose. “Get set.” She brought the machete down in a hard straight line. Whack! The chicken’s head shot off to the side as the blade hit the wood. Quickly she picked the chicken up and set it on its feet. “Go!” she shouted.

The headless chicken dashed off. Its wings flapped, its feet clawed the air. It hopped and zigzagged in all directions. The blood shot up from the red hole in its neck like bursts of smoke from a runaway train. It ran beneath a sticker bush and we crawled under, scratching up our backs. It scampered behind a pile of bricks. We followed. It suddenly turned around and flew right at us.

“Arghhh,” Pete shouted, covering his face with his hands.

A big hot splash of blood shot out of its neck and hit me in the eyes. I stuck out my arms and blindly snatched the chicken out of the air. I held the headless chicken up over my head. “I won! I won!” I shouted. Blood dripped from its neck and ran down the inside of my arm.

Pete crawled out from under a bush. He had a fresh clot of blood stuck to his forehead and he looked as if he’d been shot between the eyes.

“Let’s do it again,” he shouted.

But the chicken was out of steam. When I set it back down on its feet, it fell over like a windup toy that had wound down.

“It’s drained,” Marlene said. “Finished.” She should know. She was the chicken expert.

Suddenly the back door to the kitchen flew open and Betsy stepped forward and stood on the landing with her hands on her hips. She was angry. “You’ve become a bunch of savages,” she shouted. “Look at yourselves.”

Marlene shrugged.

“We’re just playing,” I yelled back. I was covered with chicken blood. It was drying on my clothes in crusty brown-and-red patches. It was matting up in my hair. It was smeared across my face and under my fingernails.

“Well, you should read Lord of the Flies,” she said smugly. “Then you’ll see what happens to people who are stranded on tropical islands.”

“We’re not stranded,” I shouted, and wiped my bloody hands on the back pockets of my pants.

“As far as I’m concerned, we’re stranded,” she said.

It had been two months and she was still mad because we had moved to Barbados from Fort Lauderdale. She complained that we had left civilization behind. I would never call Florida civilized. People might dress fancier in Florida, or drive new cars, but every time you picked up the newspaper they were shooting each other over money and drugs. People here didn’t have a lot of money, but they were nice. To me, that is what civilization is all about.

Then she pointed at Pete. “You, come with me,” she ordered. “You look like a cannibal.”

He had wiped his bloody hand across his mouth and did look like he had eaten a hunk of raw flesh. “Don’t go,” I said.

“Don’t listen to him,” Betsy insisted. “He only gets you into trouble.”

Pete looked at her, then at me. “Come on,” he said to me. “We have another chicken to catch.”

Yes! I thought. Pete is on my side. He is under my control.

“You’re making a big mistake,” Betsy warned him. “If you listen to Jack, bad things will happen to you.”

“Don’t listen to her, Pete,” I whispered. “The heat has gone to her head and she’s miserable because she can’t find any friends.”

“Don’t say I didn’t warn you,” she shouted to Pete.

“When you see what Jack turns into, you’ll come running back to me. Hopefully, it won’t be too late to save you.” She stepped inside and slammed the door.

He’ll never come running back to you, I thought. Pete is mine.

“Are you ready?” Marlene asked. She had the second chicken held down on the stump and it was squirming.

“Ready,” Pete replied and puffed out his chest.

Whack! Marlene chopped off the head. I snatched it in midair and stuck it onto my fingertip as the beak opened and closed without a sound. Marlene set the chicken on the ground.

“Go,” she hollered.

I let Pete get a head start. I figured it was good to let him catch the chicken, since he had just listened to me over Betsy. It was his reward. But I made him earn it. I pushed him out of the way, then tripped, fell, and grabbed my foot. He got up and chased the chicken around the pepper plant. Actually, my foot really hurt and I lay on my back with my foot between my hands and moaned as I rocked from side to side. It felt as if I had stepped on a long thorn. I examined the top of my foot and gently ran my hand over the skin to check if the thorn had come all the way through. It hadn’t, but the pain was killing me.

Finally, the chicken ran out of blood and Pete caught it by the wing and dragged it back to Marlene.

“What’s wrong with you?” he asked as he passed me.

“I must have stepped on something,” I said. I stood up but put all my weight on my left foot while I managed my balance with the toes of my right foot just touching the ground.

Marlene sat down on the stump and began to yank the feathers off the chickens. “You boys better clean up or your mother will be vexed with me.”

She was right. If Mom saw this much blood on us she would have a heart attack. We went to the back of the garage and turned on the hose. I sprayed Pete down and rubbed the blood off his face and arms. Then he washed me. The blood didn’t come out of our shirts very well, so we hid them inside the garage. Mom had seen centipedes in there and didn’t go in very often.

I hopped on one foot back around to the side of our house to my bedroom windows. I loved my bedroom. The windows were tall and had hinges on them, so that they opened out like French doors. From the lawn I stepped right into my bedroom. I liked having my own entrance. If I wanted to sneak out at night, I could just open my windows and take off.

I limped over to my bookshelf and pulled down a large volume on table manners written by Amy Vanderbilt. I gave it a shake. It rattled inside like a drawer full of silver spoons. The title was printed in gold lettering. I wondered if I could scrape the gold off and sell it. I certainly didn’t want to read about table manners. I already knew them all. Chew with your mouth closed. No burping. Say please and thank you. Don’t blow your nose in your napkin. I sat down on the floor with the book across my lap and worked off the three rubber bands which held the covers and pages together. It’s not that the book was worn out from use. Someone must have given it to us as a gift, because a book on table manners is not something Mom or Dad or even Betsy would go out and buy. They all knew that even if Pete and I read

the book a hundred times we’d still chew food with our mouths open, prop our elbows on the table, and burp like pig-men.

This book was my toolbox. It was hollowed out inside. I opened it up and searched through the old tools I had stored within the carved-out pages.

One day before we had left Florida to live in Barbados, Mom had come into my room with her industrial-strength vacuum cleaner.

“I have something big to tell you,” she said.

I was suspicious. Any minute, I expected her to lunge at me with the vacuum nozzle and try to suck the wax out of my ears.

“We’re getting ready to move two thousand miles away. Your dad got a new job in Barbados.”

I already knew this. Betsy had overheard them talking at night and had told me.

“Well, I want you to know that we can’t take everything we own. We all have to make some sacrifices. You can bring your clothes, your books, and your diaries. But not”—and she waved the vacuum nozzle around the room—“all this junk. Candy wrappers. Bottle caps. Insects. Newspaper clippings. And I mean it. So get rid of it, or I will.”

She turned and marched out of the room, leaving the vacuum behind as a threat. The first thing I did was open the vacuum cleaner and go through the dust bag. I had hidden a few dried bugs in Betsy’s room, but since Betsy hadn’t screamed and come after me with a shoe, I figured Mom had found them first and sucked them up. And, sure enough, they were in the dust bag. I picked them out and

blew the dust off their cracked skin. Then I slipped them into my top pocket.

Mom and I had been fighting over my junk for a long time. She thought I was too old to collect stuff that she claimed had no meaning. But my junk meant everything to me. We had already moved about a dozen times, and I wouldn’t have any souvenirs of where I had lived, who my friends and neighbors were, and what schools I went to, unless I saved little bits and pieces of it. I had already learned how to save a lot of my flat junk by hiding it in my normal diary. I had stapled in my baseball cards, glued in my stamp collection, taped in my pennies, as well as my photograph collection, newspaper clippings, Chinese fortune-cookie fortunes, postcards, and gum wrappers. But chunky stuff, like rocks and shells and bottle caps and marbles, was difficult.

Then I had remembered a movie where a detective took a big heavy book down from a library shelf and opened it up. Inside, the book was hollow. The middle of all the pages had been carved out, which left a big hole behind. Inside the hole was a bottle of poison. I didn’t have poison, but I liked the sneaky hiding place inside the book. So I went out to the living room and took a bunch of old books that nobody ever read down from a shelf. Then I went out to the garage, where Dad kept all his carpentry tools. With a wallboard knife, I cut out the middle of the pages. It was easy. Then I went back into my bedroom and began to fill the books up with all my junk.

When it came to my tool collection, I carved out the inside of the fat Amy Vanderbilt book on table manners.

When I finished, I put in my pliers, screwdriver, tack hammer, screws, nails, nuts and bolts.

That was two months ago. Now I took out the needle-nose pliers. I had to perform surgery. Whatever I had stepped on throbbed like a bad tooth. When I held a mirror up to the bottom of my foot, I saw that it wasn’t a thorn or a piece of glass. It was a plantar wart about the size of a tiny cauliflower. “Wow,” I said when I saw it. “Gross.” I put the mirror down and touched it. “Ouch,” I cried. I looked at the wart again. I couldn’t believe something was growing on me, growing in me. What nerve. But it scared me. It was like something alien taking over my body. As though I might suddenly grow a second nose or a third ear. I couldn’t let the wart take over my body. I grit my teeth and got a deep grip on it with the pointy tips of my needle-nose pliers.

“So long, Mr. Wart,” I growled. “One … two … three.” I squeezed down on the handles and yanked the wart straight out. I thought I heard something rip.

For an instant I felt relief, then suddenly the pain hit me like a hot needle jammed into my foot.

“Aggghhhh,” I moaned and rolled over on my side. I held my breath and fought back the pain. “Mind over matter,” I said to myself, and pounded the floor. “Mind over matter,” I repeated. But I was losing the battle. The pain roared back and blood squirted out of the hole just like it had squirted out of the chicken necks.

I crawled over to my bed and pulled myself up by the headboard. “Oh, crap,” I said. “Oh, crap.” I hopped over to the door and opened it. I peeked down the hall. Betsy

had her door closed, and no one else was in sight. I hopped on my good foot and leaned against the wall. Every now and then my hurt foot touched the floor and I nearly hit the roof.

When I got to the bathroom I locked the door. I held my foot over the bathtub spigot and turned on the water. “Aggghhh.” It burned.

When the blood slowed, I wrapped the hole with gauze from the first-aid kit and taped it up.

Suddenly I heard Betsy shout. “What’s this blood in the hall?” She pounded on the bathroom door. “Open up!” She tried the knob. “You know you’re not allowed to lock the door.” She pounded on it again. “Is this chicken blood?”

“No,” I shouted, and hurried to wipe up the blood in the tub with toilet paper and flush it down the commode.

“Mom!” she hollered. “Mom! Come here.”

Then Mom was pounding on the door. “What’s all this blood?” she asked.

Now Betsy’s done it, I thought. I took a deep breath and opened the door. “I only yanked a wart out of my foot,” I said casually. “I just put on a bandage. It’s no big deal.”

“You’re more disgusting than I thought,” Betsy said and twisted up her face into a warty shape.

“Did you clean it out well?” Mom asked.

“Yes,” I replied.

“Did you use peroxide?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said, lying.

“Okay, then. Just clean up the hall.”

“Disinfect it,” Betsy added. “Use hot water. I don’t want any voodoo wart seeds getting on my feet.”

“There is no such thing as a wart seed,” I said.

“Just look in the mirror,” she cracked back.

“Enough,” Mom ordered. “Jack, clean the hall.”

“Okay,” I moaned, and hopped away like a lame rabbit.

That night my foot was killing me. I sat on my bed with a penknife and carved a little hole into the cover of my diary. When it was big enough, I removed a wad of tissue from my shirt pocket. I unwrapped the tissue and inspected the wart. I didn’t want to touch it, because of the wart-seed idea. I didn’t want a family of warts growing on my fingertips. I jabbed at the wart with the point of my knife, then pressed it into the hole with the handle. Just to be on the safe side, I stuck a piece of clear tape over its bumpy surface. It looked like something dead in a glass coffin. “Rest in peace,” I whispered.

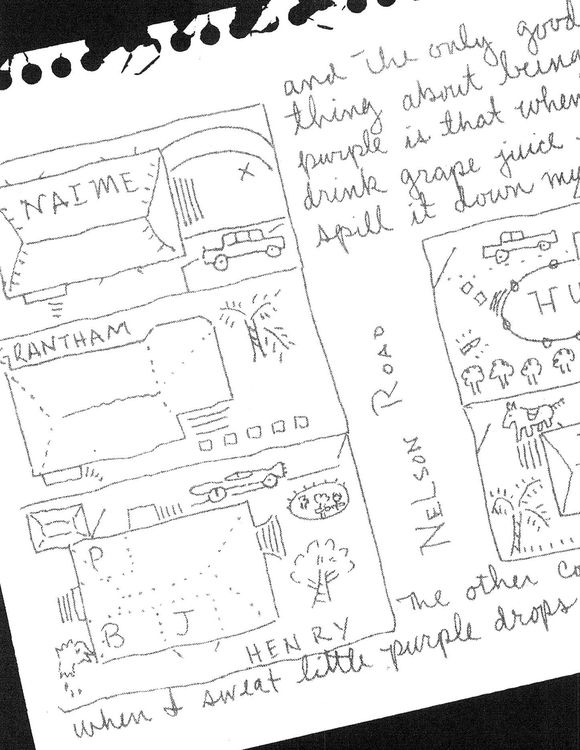

I opened my diary and drew a rough map of our neighborhood over both pages. I wanted to make a list of all the people who might be my friend. I didn’t want Betsy to beat me at making new friends. She was always boasting that she was more popular than I was, because I was clueless on how to be a friend. But I knew more than she thought I did. Dad had taught me the rules. Being a good friend meant you were a good listener, always told the truth about what you liked and disliked, and tried to lead by example, not by threats. And you had to know how to tell good jokes and stories. I knew he meant that telling good jokes and stories was the most important part. The other stuff he just said because it was his job to sound like a parent.

I wanted to sneak up and down the street and locate the neighbors’ names so I could write them on my map. But

my foot hurt too much to creep around. I limped over to my French doors and stepped outside. I climbed the avocado tree until I was high enough to see down the street. I had my diary with me. It was dark and there were no streetlights. Each house looked like a ship out on the ocean. I could only spot the houses by the light in their windows. Actually, I could hear more than I could see. It was so quiet that I heard a boy at one house ask his mother if he could have a bowl of ice cream. She said no. I wrote “no ice cream house” down on my map of the neighborhood. I didn’t know their names yet, but I knew I wouldn’t be going there for dessert.

Every time I needed to write something down, I had to strike a kitchen match and hold it with my left hand while I wrote with my right hand. When my fingertips started to get hot, I dropped the match inside the diary and smothered it.

I watched a car turn the corner. It passed our house and stopped three houses down. A huge family piled out. They spoke loud but I couldn’t understand them. It sounded like Arabic. My grandfather was from Lebanon. He’d died before I was born, but Dad sometimes recited poems in Arabic, so I knew how their talk sounded.

Once the car doors closed, it was pitch-black. They all went inside their house, and room by room, lights appeared in the windows. I struck a match to make a note on my map. “Arabs,” I wrote.

For a long time, nothing happened. From staring out into the shifting darkness I got drowsy. I didn’t want to fall asleep and pitch headfirst out of the tree and snap my neck.

I had had enough pain for one day. I climbed down and went to bed.

Three days later I woke up speckled with boils and blisters.

“Ahhhg!” I cried out in a panic. “Help! I’m sick! I’m dying!”

I went running to Mom. “Oh my God,” she said, horrified. Then she hollered for Dad. “Jack!” she yelled. “Come here quick!”

Dad took one look at me, made a disgusted face, and grabbed his car keys. Mom ordered me to get dressed and ran to her room. As I was putting on some clothes, I heard her talking to a receptionist at Bayley Clinic. “It’s an emergency,” she said. “We’ll be right over.”

She was right. Dad drove like a maniac. “Move it, you slugs!” he kept shouting out of the window. He honked the horn the entire time, madly waved his fist, and nearly flattened a dozen people on bicycles.

The building was like Dr. Frankenstein’s laboratory. A nurse and a doctor were waiting for us. They rushed me into an examination room and told Mom and Dad to wait in the hall. The nurse made me lie down on a bed while the doctor injected a needle into my sores and withdrew samples of the pus and blood. He seemed very serious. “Did you eat anything unusual?” he asked and poked at my draining sores with a cotton swab.

“No,” I replied.

“Any bug bites?”

“No.”

“Any plant allergies?”

“No.” He didn’t ask about warts and I didn’t volunteer anything.

At the end of the examination he told me to stand up and then he escorted me to the waiting room. I put a big smile on my face to keep Mom and Dad from going crazy. But inside I was full of fear. Maybe Betsy was right and I had some voodoo chicken plague.

“I’ll call you tomorrow,” he said calmly to Mom and Dad. “I’ll have some blood results by then.”

That night I heard my parents talking about me. They were standing toe to toe in the dining room.

“I want to go home,” Mom said. “The nurse said it might be leukemia.”

“What does she know?” Dad said. “If it was leukemia, the doctor would have said something.”

“Well, I’d feel better if we were back in Florida.”

“Forget Florida,” Dad said. “We’re living in paradise.”

“It’s not paradise if you die here.”

“Don’t get carried away. He’ll be fine. Let’s just see what the tests show before we get too worked up.”

“I don’t want to take a chance on his health.”

“We’re not taking chances. You’re getting hysterical.”

Mom’s voice rose a full octave. “Hysterical!” she screeched. “If the test results are bad, we’re leaving.”

I didn’t want them to catch me spying, so I hopped down the hall on my good foot. Now I’ve done it, I thought. I’ve ruined paradise.

The next day the doctor called us back to the clinic. Mom asked him if I had leukemia.

He smiled. “No. It’s just simple blood poisoning.”

Then he turned and stared directly at me. I felt my heart racing. I thought of that little chicken just before Marlene had lowered the machete. Whack! And then she’d cooked him.

“Did you step on anything rusty?” he asked.

Mom’s eyes widened. “You did tell him about your wart, didn’t you?”

“No,” I said to her. She rolled her eyes. Then I faced the doctor. “I pulled a wart out of the bottom of my foot with a pair of pliers.”

The doctor leaned forward and placed his hand on my forehead. He must have thought I had a fever and was talking nonsense.

I looked over at Mom. She hunched down in her seat and covered her eyes with her hand.

“May I see your foot?” the doctor asked.

I pulled off my shoe, then my sock. He unwrapped the gauze bandage. “It doesn’t hurt so much anymore,” I said.

He poked at it. “It looks a bit angry,” he replied. “How clean were the pliers?”

“I found them on the street,” I said. “They were a little rusty.” I turned to Mom. She was staring at me in disbelief.

“Well, that would explain it. What you need are antibiotics for the infection and Gentian Violet for the boils.”

In a minute the nurse arrived with a big purple bottle. “Please remove all of your clothing,” she said. She unscrewed the cap and poured the medicine into a shallow bowl. Then she put on a pair of rubber gloves and dipped balls of cotton into the medicine.

I took off my clothes and watched as she painted me purple from head to toe. Mom stood to one side and smiled.

Betsy and Pete ganged up on me. Every chance they had, they made fun of me. Two days later, Mom had to reapply a fresh coat of purple paint. When I slinked out onto the breakfast porch Dad took pity on me.

“You’ve got a choice, purple boy,” he said and rubbed the top of my head. “Either we can go to the kennel and get a dog, or I can take you to the carnival.”

That was an easy decision. “Carnival,” I replied.

“Good choice,” Betsy mumbled. “There’s no reason to scare man’s best friend to death.”

“Give him a break,” Dad said. “It’s not easy being purple.”

“It’s not easy being seen with him either,” she replied.

“I’ll be ready in a few minutes,” I said. I retreated to my bedroom. Earlier I had carved a foot-shaped pad of foam rubber out of my bed pillow. I taped it into my sneaker and tried it on. When I walked a little on the side of my foot, it didn’t hurt at all. Okay, I said to myself. I’m making a comeback. Maybe I’ll find a friend at the carnival.

At the carnival we played some skill games. We threw hoops over bottles and shot at ducks and tested our strength. I didn’t win anything.

“Too bad they don’t have a chicken-chasing contest,” Betsy said when Dad stepped away to speak with a man who was working with him on the hotel renovation. “You might win a stuffed wart.”

I glared at her.

Just then a booming voice came out of the overhead loudspeaker. “Ladies and gentlemen, come into the Egyptian tent and see one of the seven wonders of the natural world. Come see and hear the incredible life of the Alligator Lady. She walks! She talks! She crawls on her belly like a slime-y rep-i-tile!”

“Let’s go there,” I said.

“I have a better idea,” Betsy said. “Let’s put a tent around you … ‘He’s poxed! He’s purple! He chases headless chickens like the purple freak he is!’”

“Come on, Pete,” I said. “Let’s play some games.”

“Forget it,” he replied and wrinkled up his face at me. He was definitely out of my control. Betsy had won him over.

“You’ll be sorry you betrayed me,” I said. “Betsy will turn you into a priss.”

“Come on,” Betsy said and grabbed Pete’s arm. “Let’s go look at the baby goats. They’re so cute.”

“See what I mean,” I said.

I waited until they were out of sight. Then I went to the baseball throw. The man running the booth eyed me suspiciously. I bet he wanted me to wear gloves. For some stupid reason I had tears in my eyes, and when I threw at the bottles, I couldn’t hit a thing. The first two balls missed by a mile. I threw the third so wide of the mark I hit the operator’s coffee cup. It flew off the table and smashed against a chair leg.

“Hey!” he said. “You’re going to have to pay for that.”

“You’ll have to touch me first,” I shot back, then turned and ran. Being disgusting was good for something. I dodged a bunch of people as I cut down the path past the

game booths. Everywhere, there were painted signs and posters of silly clowns and goony animals with crossed eyes and crazy costumes. I must have looked like one of them that came to life. A kind of diseased Pinocchio, I thought. I kept running and people kept stepping out of my way. I passed the bumper cars, the Ferris wheel, the spinning teacups, the centrifugal force machine. I felt like I could run forever. My foot didn’t hurt at all. I wanted to run home. I just didn’t know the way.

When I slowed down I didn’t see anyone from my family. I spotted the Alligator Lady tent and walked over to get a closer look. They charged a dollar, so I paid up and went in. It was dark and I didn’t seem so purple. Egyptian flute music was playing from a tinny speaker. There was a little stage with a grassy curtain and papier-mâché palm trees. In front of the stage, men were lined up about three deep. It was hot and smelly under the tent, like a swamp. A barker in a dirty white suit and pith helmet was explaining that the Alligator Lady was netted by Egyptian fishermen on the Nile. “She’s the cousin of mermaids … She is over a thousand years old and has seen her husband killed by Napoleon’s troops and turned into riding boots.”

The music speeded up. The curtain lifted and a large woman in a reptile suit crawled out. I could see where the zipper had split down the side of her costume. She must have gained a little weight. A long alligator mask was strapped to her face with thick green elastic straps. They tried to disguise the phony suit by sticking a lot of slimy leaves and pond scum all over her.

She crawled across the stage on her belly like someone

crawling under her bed. She peered up at the circus barker and hissed.

“She’s a fake,” a man said.

No kidding, I thought.

At first I felt cheated when I saw she was a fake, but then I didn’t mind. I really felt sorry for whoever was in that costume. I should be her friend, I thought. I could run away and join the circus and live with the freaks and they would accept me as the purple boy and be my friends.

“You can ask her questions,” the man in the white suit said. “She can predict the future.”

“When do I get my dollar back?” asked a wise guy.

The Alligator Lady cocked her head and turned to glare at the man. “Listen,” she said in an irritated tone. “I’m hot and sweaty and this is the only job I could get, so give me a break.”

Everyone took a step back.

“Hey honey, don’t bite,” the wise guy said.

The man in the white suit waved his cane over his head. “She is not feeling well today,” he said. “Her malaria is acting up.”

I wasn’t feeling well either. Suddenly I thought I might vomit. I didn’t want to throw up and steal the show. I turned and went back outside. The light was so bright my head hurt. Maybe I have a headache, I thought, though I wasn’t sure what a headache was supposed to feel like. In the movies, when people had headaches, they went to bed or fainted. When Mom had one, she seemed grouchy. When Betsy had one, she didn’t want to do anything but pout.

My eyes hurt. Maybe I don’t have a headache, I thought. Maybe I really am sick. Maybe I have a deadly disease and no one has the guts to tell me. Maybe Dad brought me to the carnival for one last good time before I croak.

“Hey, purple chicken eater,” Pete said, sneaking up behind me. “Where’ve you been?”

“None of your business, Betsy’s pet,” I replied.

He stuck out his tongue. “Look what I won.” He held up a stuffed red devil.

“I bet Dad won that for you,” I said.

“Betsy did.” He frowned. “What’s wrong?”

“Headache,” I said and shielded my eyes from the sun. “I need to lie down.”

That night my foot felt better. It was still sore if I stepped hard on the wart hole, but if I wanted to make friends before Betsy, I had to get going. She was already starting to plant flowers in the front yard, and it wouldn’t take long before a neighbor stopped by to introduce herself. Betsy’d pounce on her like a cat. I’d never hear the end of her calling me a “friendless purple freak.”

I got my diary and map and opened my French doors. In the darkness no one could tell I was purple. I removed a kitchen match from my pocket and stooped down to scratch it across the asphalt. It snapped to life. I shielded the flame behind my diary and walked a little ways until I came to a driveway. My match went out and I stood still until my eyes adjusted to the dark. When I looked around, I saw the faint outline of a white mailbox. I leaned toward it and struck another match. NAIME was painted in big red

block letters. It was the Arabs’ house. I dropped down to my knees, opened my diary, and wrote NAIME on my street map. One down, I thought. I jogged for a little bit, until I thought I must be close to another mailbox. I stooped down and struck another match. There it was. HUNT. I wrote that down on my map. The next house was easy because their porch light was on. GRANTHAM. Then there was a lot of darkness. I jogged for a little distance and lit another match. Nothing. I jogged some more. The road curved to my right and I kept jogging. It felt good to run a bit. I wanted to get my health back.

I stopped and lit another match. I found a driveway, or was it a road that took a left turn? I couldn’t tell. I didn’t see a mailbox, so I jogged a little ways farther. I lit another match and found I was standing next to a bicycle that was propped against the front porch stairs of a big house. I dropped the match and stepped on it as I crept back out of the driveway before someone threw a net over me. I crossed the street and checked for mailboxes on the other side of the road. I lit a match and just then heard footsteps.

“Hey!” a boy hollered. “Hey!”

I threw the match down and started to run. I figured I was going in the right direction.

“Hey!” he said. “Stop.”

I picked up my pace.

He picked up his pace.

I turned it on. My foot throbbed, but I wanted to get home. I didn’t want someone to catch me snooping around. They might think I was a burglar and I’d get a bad reputation and never make a friend.

“Hey,” he shouted. He was gaining on me. “Slow down.”

I speeded up. If my foot wasn’t so tender I could take off and leave him in the dark.

He speeded up.

I turned it on even more.

The steps kept coming. They were right behind me.

“Hey. Hey, you.” He reached out and tapped me on the back.

I kept running.

“Hey,” he said. “Slow down.”

I was doing that anyway. My lungs felt like they were being ripped out of my chest. My feet slapped at the tar as I slowed down. My foot throbbed.

He slowed down, too.

I put my hands on my hips and walked in a wide circle. He did the same.

“Are you new?” he asked between breaths.

“Yes,” I huffed. Even though it was dark I covered my purple face with my hands and diary. I stared out at him. He was only a slightly darker shadow against the night.

“Where do you live?” he asked.

I paused. The houses didn’t have street numbers, just names. Dad had painted HENRY on a piece of wood and wired it to the front gate.

“Henry,” I replied.

“So, you’re the new kid,” he said. “I heard a new American family had moved in.”

“Yep,” I said. “That’s us.”

He must have stuck out his hand to shake mine, but because it was so dark, he kind of poked me in the stomach.

I jumped back.

“Sorry,” he said. “My name is Shiva.”

“Jack,” I replied, thinking that Shiva was an odd name for someone with an English accent. I stuck out my hand and searched for his as if I was reaching for a doorknob in the dark.

“Do you want to join our track club?” he asked.

I did, but I said, “Not just yet. I need to practice some more.” No club would have me until I got rid of this purple stuff first.

“Well, I’ll pass by sometime and we can run,” he said.

“I only run at night,” I said. “It’s cooler.”

“Me too,” he said. “But presently I must return home.”

“Okay,” I said. “I’ll see you tomorrow night.”

“Yes,” he replied, “and I will look into what you need to join the club.” Then I heard his footsteps running off behind me.

I went directly home. My heart was pounding. I had a friend hooked, but could I reel him in? Or would I lose him once he saw me in the light of day? But for now I didn’t have to worry. We could run at night.

The next morning, after breakfast, Betsy was back out in the front yard planting marigolds. She had a pitcher of iced tea and two extra glasses. She was waiting for anyone her age to walk by so she could offer them a drink. She was going to beat me at making new friends. Since it was daytime, I figured my strategy was to keep her from getting a friend, instead of me finding one.

I ran back inside my bedroom and got my medicine. I put on a white T-shirt and wrote BETSY’S BROTHER in Gentian Violet across the front. Then I dabbed more on my

face. I went out to the front porch and took a seat next to her table with the iced tea. She was working with her face to the street, so she didn’t see me. She could plant marigolds all day and no one would stop to talk once they saw me sitting up there like a purple freak. They certainly wouldn’t want any iced tea if they thought I’d drunk out of the same pitcher.

A car drove by. I stood up and pointed to my shirt. The driver smiled and waved to me. God, I thought, people here are so nice I can’t scare them away.

A second car rolled down the road. Once again, I stood up and pointed to my shirt. The driver slowed down and turned into our driveway. Betsy straightened up and rubbed her hands together to shake off the garden soil. She figured she had nabbed a victim. I smiled a great big goony smile, crossed my eyes, and waved my hands over my head. I stuck out my tongue and pushed my finger halfway up my nose.

The back door opened and a boy about my age got out. He wore a bright green silk jacket down to his knees. It sparkled under the sun. On his head he wore a silk hat the shape of an upside-down rowboat. He waved to Betsy and asked her a question. She turned and I could tell that she was surprised to see me standing on the porch. Just the way her eyes narrowed and her fists clenched told me she was furious. Pete must have heard the car. He came running out. When he read my shirt he started to laugh.

The boy waved to me. I gave him a wave back and then it struck me that he was the kid I had talked to in the dark. And I was purple. The full sun was directly above us in the blue sky and I was bright purple. I glowed like a neon sign.

He walked up the front steps and stared at me for a moment. I wiped my hands on the back of my pants.

He stuck out his hand to shake, and I did.

“You are purple,” he said quietly. “Purple is a very distinguished color.”

His face was the color of clay pots. His hair was jet-black. His lips were pink. “You’re …”

“From Pakistan,” he said, helping me out.

“This is my brother, Pete,” I said. “He’s not purple, but we like him anyway.”

Shiva smiled. He opened his jacket and removed a pamphlet from the inside pocket. “I wanted to give you the information on the track club,” he said.

I took it from him and set it on the table with the iced tea. My hands were sweaty and I left purple fingerprints on the paper. “I think,” I said slowly, “that it would be best if I joined after I got over this purple problem.”

“Perhaps, yes,” he said. “I understand. Although it is a very nice shade of purple.”

I was certain he was the most polite person I had ever met, and I desperately wanted him to be my friend. “But we can still run at night,” I suggested. “My foot was hurting me, but it’s gotten better.”

“Very good,” he said. “I will see you tonight. For now, I have to go.” He turned and nodded toward the car. His father waved at me. All of his teeth were gold. I waved back.

“Come by after sundown,” I said. “Knock on the French doors on the side of the house.” I pointed to where they were.

“Very good,” he replied, and nodded. He walked

quickly down the stairs. He said something polite to Betsy, then got back into his car.

As they backed out of the driveway Betsy marched toward me.

Pete tugged on my hand. “Can I run with you?”

“Forget it, traitor,” I replied. “You can stay home and plant marigolds with your new friend.”

Before Betsy could reach me I pulled the shirt up over my head. “I won’t be needing this anymore,” I said to her.

As she tramped past, she grumbled, “You’ll always be a freak to me.”

I threw my shirt into the front yard. “That’s why I have friends,” I replied.