It was the middle of summer and the flies were driving us nuts. There were millions of them. We were overrun. Our house didn’t have window screens, so they buzzed us all day and all night. But I had a plan. I knew that if you want to wipe out snakes you introduce the mongoose, its natural enemy, and before long the snakes are eaten and gone. If you want to get rid of mice, you buy a cat. And I knew that to get rid of flies you bring in lizards. So I did. I went out to the back yard and trapped a dozen and set them loose in my room. At first it was great. They zapped the flies with their long sticky tongues and swallowed them whole. But soon they ate so many they got fat and full and lay about the room with their eyes closed and arms and legs spread open like burned-out tourists.

I stomped around the floor with a ruler, shouting, “Wake up! Time to sing for your supper. Eat! Eat!” I

slapped the ruler against the wall and startled them into moving their lizard lard. But they were useless and only lurched forward a few inches before taking another siesta.

“Forget that idea,” I said out loud. “This is a man’s job.”

I got the flyswatter and went to work. Whack! One down. Whack! Another. Killing them properly is all in the wrist. If I swatted them with too much force, I splattered fly juice all over the wall and had to scrub them off with a rag dipped in bleach. It worked better to snap my wrist very crisply, like hitting the triangle in music class.

Whack! Whack! Whack! I became bloodthirsty. One at a time wasn’t good enough. I lined up two at a time. Three at a time. I swatted them out of midair. Eventually I became so fast I grabbed them with my bare hand and held them underwater in the sink until they drowned. By the time my frenzy was over, I counted 173 dead. But it didn’t make a dent in the fly population. One hundred and seventy-three flies immediately buzzed through my window and took their place. I tried to rally my lizard workers to eat more. But they were stuffed, and when I smacked the ruler around their tails they wouldn’t even tremble. I accidentally hit one and cut its tail off. I picked it up and pressed the broken part against the tip of my nose. The lizard blood was thick and gummy. The tail wiggled around like a tiny bullwhip. “Mush. Mush!” I shouted and lowered my nose so the little whip lashed their backs. They didn’t even twitch. They stuck to the wall like refrigerator magnets.

I collected my flies and pressed them into my diary. Crunch! It was like making a fly sandwich. Then I took a pen and wrote 173 on the plastic flyswatter flap. I planned

to kill one million, save them for proof, and get into the Guinness Book of World Records.

But after a while the flies were no challenge. I had to move up. I had to find something more difficult to exterminate. I was getting older and killing flies was a kid’s game. I went out to the back yard. We had an abandoned well filled with bats. The well opening was cemented over except for a hole the size of a brick. Every evening a ribbon of bats flew out of the hole to eat insects. They spread out and darted overhead, cutting the air up into little jigsaw pieces. Now they were difficult to hit. That was a challenge.

The only problem was that Dad had told me not to mess with them. “They are animals,” he said. “You never throw rocks at animals.” He told me this after he caught me whipping broken shards of bathroom tile at them. He said he was worried about me hurting the bats, but I knew it was really that he was worried about where the pieces of tile and rocks would land. There were a lot of houses around and he was touchy about breaking windows.

Johnny Naime told me that it was impossible to hit a bat with a rock. “They have built-in radar,” he explained. “You can throw rocks at ’em all day and never hit them. You can’t even shoot a bat. They move faster than bullets.”

Cool, I thought. They were just the challenge I was after.

I got a yardstick and poked it down into the hole and stirred it around. I didn’t hear anything. I put my eye to the hole and looked in. I was a bit afraid one of them

would come shooting out and bite me on the eyeball, but I knew that was impossible. Dad said they ate only bugs and vegetables.

Just then BoBo II brushed against the back of my leg. I jumped up into the air. “God! You scared me.”

Betsy had got him as a birthday gift. She named him after her other black spaniel, BoBo I. That was a mistake. BoBo I was a loser, and this one was even worse.

He rolled over and fell asleep. Something was wrong with that dog. It needed vitamins. And it smelled.

Suddenly a bat flew up out of the hole and fluttered back and forth overhead. I picked up a bunch of rocks and fired at it. I didn’t even get close.

Then a stream of them came out in a steady black line. They zipped back and forth above the house eating millions of flies. “Eat more!” I shouted. “Get fat! Slow down and I’ll nail you.” I threw about a hundred rocks. Everything missed. They were about a million times harder to hit than flies.

As quickly as they had all come out of the hole, they returned into it, like the smoke sucking back into Aladdin’s lamp. I waited a few minutes for them to settle down, then picked up a brick.

“If their radar is so good,” I said to BoBo II, “then they can dodge rocks in their sleep.” I dropped the brick down into the hole. Nothing happened. I chucked a few more pieces of brick into the hole.

A single bat came out of the well and dove at my head. It startled me and I yelled and tripped backward over BoBo II. My feet went up over my head and the bat zoomed in on my sneaker and bit it on the rubber tip. I

didn’t know what bat teeth looked like, but they went through my tennis shoe and missed my toe. If it’s a vampire bat, I thought, I’m a quarter-inch from being turned into a vampire and living with Dracula for the rest of time. I had seen the movie.

I pumped my foot up and down, but I couldn’t shake it off. I threw a rock up at it, but missed and hit my ankle. I picked up another rock and whipped it at the bat. I missed, but I heard the sound of breaking glass. Oh crap! I thought. What had I hit?

But I still had the bat to deal with. I used the toe of my good shoe to wedge the heel off my bat shoe. It fell to the ground, but the bat hung on. I jumped up and hobbled off to find what I broke.

It couldn’t have been worse. It was Dad’s office window. “Ay, chihuahua,” I moaned. “Now I’ve done it.”

This was the second time I’d broken Dad’s office window. The first time, I hit it with a tennis ball. I was playing by myself against the garage door when I smacked the ball right through the pane. It was an accident.

Dad gave me a warning which basically went: “If it happens again, I’m going to use my belt.” He meant business.

I wanted to run but knew hiding would just make it worse. As Dad would say, “Take your punishment like a man.” He was right. I couldn’t act like a boy forever. I was already thirteen. I squatted down and picked up all the glass shards. When I was little, I always called broken glass “ghost’s teeth.” That seemed like a thousand years ago. This was just broken glass, plain and simple

After I cleaned up, I wrote a note and taped it on his office door. I didn’t tell him about the bat. One thing at a

time, I cautioned myself. Then I returned to my room to wait. Maybe he would just come in and tell me one of his lesson stories. I flipped through the section of my diary where I wrote them down. There wasn’t one for my particular problem.

“Once upon a time,” I wrote, “there was a son who didn’t listen to his father. He repeatedly screwed up. But the father was patient. And eventually the son figured out how not to get into trouble every day of the week. Eventually he thanked his father for his patience.”

But that evening, when he opened my bedroom door, his belt was already off. I didn’t even get a chance to explain my side of the story.

“You know the rules,” he said.

“It was an accident,” I replied, lowering my eyes.

“There is no such thing as an accident,” he said, quoting himself. “There is right and there is wrong. There is thoughtful thinking and thoughtless thinking. Your thinking today was thoughtless and what you did was wrong. That is not an accident.”

I felt trapped by his thinking. “It was an accident,” I said weakly. “Don’t you get it?”

“Children have accidents. Men make choices. Just do as you’re told,” he replied impatiently.

I put my hands out and leaned against the wall. He reached into my back pocket, removed my wallet, and flicked it onto the bed. Then he reared back and gave me five cracks in a row.

When he finished he slid the belt through the loops of his pants. It looked like a snake curling around his waist.

“You’ll never grow up properly if you don’t listen to me,” he said, and left the room.

I pulled down my pants and sat on the cool floor. I decided I’d never let this happen again. I’d never break his window and I’d never let him hit me. I was tired of being on the bottom of the heap. I wanted some power of my own. I was sick of beating up flies, lizards, and bats. Those were kids’ games, and the longer I played like a kid, the more I was treated like one, and the less power I had.

That night, when Mom and Dad came home from the Beau Brummell Club, they started arguing. I listened at my bedroom door. From the volume of their voices I could tell they were in the living room. They were arguing about the same stuff they always fought over. Mom wanted to return to Pennsylvania. She didn’t like being so far away from her family.

“Nonsense,” Dad replied. “If we lived back there, I’d be out in the snow framing houses for peanuts. That place is a dead end. We have no future there.”

“Well, what do we have here?” she asked. “A bunch of rummy friends and no family.”

He poured a drink. “We have friends,” he said.

“And you are drinking too much,” she added.

“Don’t start that again,” he snapped, and sat down heavily on the couch.

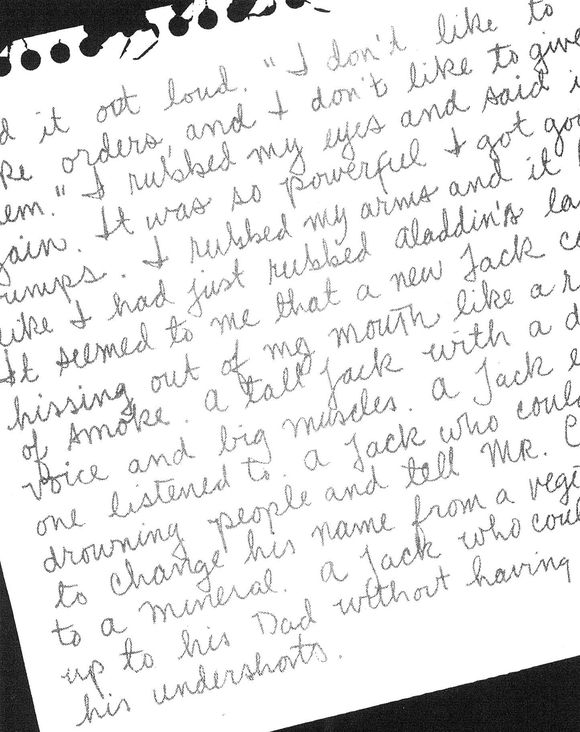

I picked up my diary and put a pen between two blank pages. It’s now or never, I said to myself. I’ve got to fight back. If he wants me to listen to his every word, I’ve got to be close enough to hear them all. I took a deep breath, opened the door, and went down the hall. I stood by the

dining-room table and stared at them. Dad was spread across the couch, with his head propped up on the arm. Mom was standing. Her black evening shoes dangled in her hand by their heel straps. She had a tissue in the other hand and was wiping off her red lipstick. I caught her speaking in midsentence.

“ … and I called Mother,” she said, “and told her I wanted to come home for a few weeks.”

“Do what you want,” Dad said, and waved at a fly. “I can get along just fine without you complaining all day and night.”

Then he saw me. He hopped up onto his feet and put his drink down as though he hadn’t said or done anything nasty.

Just like an adult, I thought. Always trying to act innocent. They use one set of rules around us and another for themselves.

“What are you doing up?” he demanded.

Mom propped her hand on her hip.

“Writing,” I replied, trying to keep my voice steady.

“Writing what?”

“In my diary,” I said.

“He means what are you writing?” Mom said, stepping between us.

Then I unleashed the line I had been waiting to use. The one that I hoped would turn the tide and put me in control.

“I’m writing down all the things you say,” I replied. I looked down at my diary and began to write his last question.

“Stop it,” he ordered.

I wrote down Stop it in my diary.

“I think you should return to your room and read,” Mom suggested, crossing her arms. I slowly wrote down what she’d said.

“Let me see what you’ve written,” he commanded. He was angry. He picked up his drink and finished it. When he lowered his glass his eyes were red and narrow. My grandmother had once said to me, “Alcohol can turn the gentlest lamb into a lion.” I believed her.

“Give me that.” He held out his hand.

“No,” I said. “When Mom gave me the diary she said it was mine.”

He groaned and rolled his eyes. “Your mother told you that?”

“Yes.”

Mom took a deep breath and let it all out slowly. “Anyway,” she said to Dad, “I don’t want to talk about it tonight.”

Dad took a step toward me. I bit my lip. Here he comes, I thought. Don’t look away. No matter what he does, don’t look away. He’s going to grab my diary and toss it across the room and take out his belt. But he didn’t. He ran his hands through his hair, turned, and left the room.

“If I were you,” Mom said once he was safely down the hall, “I wouldn’t try this stunt too many times.”

Why not? I thought to myself. It worked. I’ll do it a hundred times in a row if I want to.

“And another thing,” she said. “I don’t like your attitude.”

Great! I thought. I could feel the new power in me. The power to annoy her.

“I think you need to go to your room,” she said.

“Fine with me,” I replied. “It will give me more time to write all this down in my diary.”

She groaned. I could tell she regretted getting me a diary. But it was too late to take it back.

I stood up and retreated down the hall. I was feeling very powerful as I closed and locked my bedroom door. I opened my French doors and stepped out. I climbed up into the avocado tree and looked up and down the street. I was taller than any of the houses. I was taller than Dad. “The pen is mightier than the sword,” I whispered. I finally understood what that meant.

A few days later Mom opened my bedroom door and sat on the edge of my bed. She had just returned from having her hair and nails done. “I have something to tell you,” she said seriously. “Sit down.”

I sat next to her and sniffed the air. She smelled like hair spray and nail-polish remover and lots of gardenia perfume. I took a deep breath and held it in.

“I spoke with Grandma and have decided to go up and visit her for a month. I’m taking Pete and Eric … but you and Betsy have to stay here.”

“Why?” I blurted. “I’m always left behind.” I felt betrayed.

“Because your father and I had a talk and agreed that if we stay in Barbados longer than the summer … maybe for a long time … you will have to get ready for school here.”

“But it’s July,” I said. “July!”

She paused. “You have to go to summer school,” she

said. “The school system here is more advanced than in Florida. If you don’t go to summer school to catch up, you’ll have to repeat sixth grade.”

“No way.” I groaned. Florida was screwing me up again. I had told her my last school was for simpletons only, but she didn’t believe me. Now she knows, and I have to suffer the consequences. As usual.

“Which means,” Mom continued, “that you have to stay here with Betsy and Dad for a month. I know this is not fun, but Marlene will cook and keep your clothes clean and you are old enough to be responsible.”

“I’m old enough when you want me to be responsible so you can do what you want. But I’m always too young when it comes to doing what I want.”

“You’re not a kid anymore,” she said. “You are a young man. Act like one.” She stood up. “I don’t want to hear any back talk,” she said in her bossy voice. “You understand that this is the best situation we can work out for everyone. This whole family doesn’t revolve around you and your needs.” She frowned, which meant she had spoken the Truth According to Mom and that was that. She left the room.

“You’ve just thrown me to the wolves,” I shouted. “The wolves!”

She opened the door and smiled at me. She was so beautiful I forgot to be mad. “Your sister said the same thing,” she said, and laughed. She glided toward me and gave me a big hug. “You know,” she said, “I think this will give you and your dad some time together to smooth out some of your friction.”

“What do you mean?” I asked. I was pretty sure our

relationship was about winning and losing, about who was the boss and who was the peon.

“You know what I mean,” she said. “You’re getting older and you are starting to bump heads with your dad.”

I wasn’t ready to discuss it, so I changed the subject. “I’ll miss you,” I said.

“I’ll miss you more than you’ll miss me,” she replied, and became teary-eyed, which made me feel like a jerk for ever saying anything mean to her. Even though she was leaving me with Dad and Betsy for a month, she was my mom. It was my job to be nice to her, no matter what.

Two days later they were gone and Betsy and I were eating dinner with Dad. Marlene served a platter of flying fish and okra.

“I love this fish,” I said to Marlene.

“Thank you,” she said in her formal voice. When she passed me, she bent forward and whispered, “We’ll have chicken hearts this week.”

“Yum.”

“Tomorrow,” Dad started, delivering the opening word to the evening announcements, “the driver will pick you up and take you to the prep school. Marlene will have your lunches packed. After school you’ll come directly home and do your studies. Marlene will have dinner for you every night at six. If I’m not home, eat without me and be in bed by nine. Any questions?”

Betsy didn’t argue with him. I didn’t either. I pulled my plate close to my chest, lowered my mouth, and scraped the food in.

“Look at him,” Betsy said arrogantly. “He uses BoBo II’s

rules of eating. First, eat everything as quickly as possible. Second, eat everything you dropped on the table or floor. Third, wash it down by slurping loudly. Fourth, nose around for more. Fifth, when there is no more, lick your lips and drift away.”

I stared at Dad. If Mom were here she would ask Betsy to apologize.

Dad laughed. “You know,” he said to Betsy as if I weren’t present, “the best way to feed Jack would be to put a funnel in his mouth and just pour it down his throat.”

Now it was her turn to laugh. Without Mom, I was a Ping-Pong ball whacked back and forth.

“May I be excused?” I asked, and was halfway out of my chair.

“Only if you’ll get our fishing gear organized,” Dad said. “I thought you’d like to join me.”

“All right.” I loved to fish.

I ran into the kitchen and called Shiva. We were supposed to go running later on.

“I’m tired, anyway,” he said, after I canceled. “I’m sluggish.”

“I have a cure for that. Whenever I’m sluggish, Mom always gives me prunes and warm water. I guarantee that in no time you’ll be on the run.”

“Really?”

“Cross my heart,” I said. “You’ll be running like a fiend.”

“Okay,” he replied. “I’ll try it.”

I put down the phone and headed for the garage. I got our rods, tackle boxes, net, and gaff hook, then loaded it all into the truck. I knew the routine.

When Dad arrived we drove to the St. Lawrence Gap, a stone jetty starting from the back of the St. Lawrence Hotel. It curved out into the ocean like a hundred-foot-long question mark. We carried our gear to the tip and got set up. The ocean was calm. The swells slowly brushed along the rocks and sighed as they broke across the sand.

“The first one to catch a fish gets to send the other guy to the bar to get drinks,” Dad said.

“Okay.” It was a fair deal. That’s what I liked about fishing. It put us on equal ground. You cast out your line and the fish don’t know the difference between a man and a boy.

Dad reared back and cast his chrome triple-hooked spinner. The line spun off the reel. Plop. It landed about fifty yards away. He let it sink down and slowly reeled it in with his thumb pressed against the spool of line to feel for bites. He was going for big bottom feeders like grouper and trigger fish.

I took a different approach. I opened my tackle box and attached a bobber to my line, then got my secret weapon, a dragonfly. I put it on the hook and gently cast it out so it floated about twenty feet from the rocks. I was after surface feeders, especially red snapper, which was my favorite. Together we stood there with our rods pressed against our bellies like two guys peeing off a dock.

Suddenly my bobber went under. I counted. One, two, three. I jerked back on the rod to set the hook, and reeled it in. The fish didn’t put up much of a fight, but it was the first one caught—a bluegill about the size of my hand.

“I won,” I hollered. “I’ll take a Lemon Squash.”

“You didn’t win,” he replied. “That’s not a fish. That’s bait.”

“You didn’t say how big it had to be. You just said it had to be a fish.”

“Well, you cheated,” he said. “Anyone can catch a fish like that. I could have just stuck the net in the water and caught one of those. Now you have to get the drinks.”

“No way,” I said. “I won. You haven’t caught anything yet.”

“Don’t argue with me,” he replied. “You cheated. Besides, I’m paying. Now fetch. I’ll take a Banks in the bottle. And tell the bartender your dad wants it ice-cold.”

I threw my fish back into the water and took the money from his hand. Bully, I thought to myself. There is no winning with someone who won’t play by the rules.

By the time I returned he had seen a few of his friends and waved them over. They sat down on the rocks to shoot the breeze and I couldn’t get a word in edgewise.

I recast my line and drank my soda. I should have talked Shiva into running, I thought. It would be a lot more fun than watching Dad and his pals talk. And then I remembered what I told him about the prunes. I hoped he didn’t take my advice. I was sure he knew better. Everyone knew what prunes could do to you.

The next morning Betsy and I were standing at the edge of the driveway. I looked up at Dad’s window. It was still broken.

“Don’t you get tired of being treated like a kid?” I asked.

She frowned. “Nobody treats me like a kid.”

“Well, don’t you hate it when adults say things like, Do as I say, don’t do as I do.”

“I just ignore them,” she said.

“Doesn’t it bug you that you never get a vote on where to live, what to eat, where to go to school, what clothes to buy?”

“What are you whining about?” she shot back. “You are always complaining about something. You are the last person I would want making decisions around here. If it wasn’t for Dad, you’d be living in a refrigerator box and raiding garbage cans for dinner.”

I could tell whose side she was on. I missed Pete already. He usually agreed with me. A month of Betsy and Dad and I’d be a nervous wreck.

We were standing at the edge of the driveway when a car raced up the street and aimed straight for us. It was a big old American car with a huge hood ornament, and as it got closer it looked like a charging rhinoceros. Betsy stood her ground, but I jumped behind a fence post as it hit the brakes and skidded to a stop.

“Get in,” squeaked a little voice.

The driver was a bug-eyed maniac. He was skinny, sat on a pillow, and scratched at a bald spot on his head that looked like a rug burn. He smoked unfiltered cigarettes and had a lead foot. Betsy took the front seat and sneered at him. I climbed in the back with two boys who must have been brothers, about my age and Pete’s. They were pale, sweaty, and terrified. We took off with a lurch and peeled rubber up to the corner, where he took the right-hand turn

without slowing to look. The car tilted like a canoe about to flip over. I tumbled across the seat and crunched into the two boys. They both grabbed their crotches and moaned.

“Sorry,” I mumbled. The car straightened out and we raced a taxi to the red light, where we came to a screeching stop. The three of us bounced off the back of the front seat and fell to the floor. When I pulled myself up I was thrown back as the light turned green and our driver floored it. Betsy had her shoes propped against the dashboard and her right hand gripped the overhead strap. Her left hand was pressed against the side of the maniac’s face, so he could only see with one eye. “Slow down!” she yelled.

He laughed and speeded up, then jerked his head out the window to get a better view. The engine roared as he pulled out to pass a line of slower cars and bicycles.

I glanced at the two boys.

“Okay,” the older one said to the younger. “Now’s your chance. We’re on a straight stretch.”

The speedometer needle was up to seventy-five and we were passing everything on the road. If anyone pulled out in front of us we’d be dead meat.

When I turned back toward the boys, I was shocked. They both had their pants down and were pulling plastic bags of pee off their private parts. The bags had been held on with rubber bands. The older brother, who was next to the door, threw his out the window. He then reached for his brother’s full bag. It was a delicate operation made even more difficult because the bag was so full. Before he could swing it out the window, we hit a curve at seventy and the three of us were pressed against his door with my face

about an inch away from the dripping pee bag. In an instant we straightened up and he tossed the bag out the window before we took a curve on my side.

When we straightened out again, the younger one attached a fresh pee bag to his privates and yanked his pants back up. I looked at the older brother.

“He scares us so much we wet our pants,” he shouted over the blast of air which was screaming through the open windows. “This is all we can do to stop it.”

Just then the maniac hit the brakes and we went into a sideways skid down a dirt road. We came out of the fishtail and quickly pulled into a driveway. Overhead was a sign which read ARAWAK SUMMER CAMP.

We came to a stop inches from another car and scared the passengers into ducking down. The two boys hopped out. “See you later,” I said, as we spun out in a cloud of dust and flying gravel. Up the road we pulled into another driveway. PRESENTATION YOUTH COLLEGE read the sign.

As soon as we came to a stop, Betsy reached across the dashboard and pulled the keys out of the ignition. She jumped out of her side and threw them into a field of grass.

“Hey! You can’t do that,” the maniac squealed. He sounded like an angry Chihuahua.

Betsy raised her fist to his chin. “I just did it,” she growled. “So what are you going to do about it, you little runt?”

He turned and ran into the field. He dropped down onto his knees and scratched up the ground.

“Coward,” she hollered. “It’s not nice to scare kids.”

“That goes double for me,” I yelled.

Betsy turned around and gave me the evil eye. “Oh,

shut up,” she carped. “You sound tough now, but all you did was bounce around back there like a bowl of yellow Jell-O.”

She was right. I hadn’t lifted a finger to help out.

“What could I have done?” I asked.

“You should have covered his eyes with your hands.”

I imagined just how helpful that would have been. We went inside and found our class assignments, which were listed according to grades. There were half a dozen other kids about my age scattered throughout my room. They weren’t Americans, so I figured other countries were also dishing out crummy educations.

I took a seat next to the window so I could daydream. Suddenly a very stubby, thick man marched into the room.

“Rise and stand quiet,” he ordered.

We all stood.

He set his briefcase down on the desk. “My name is Mr. Cucumber,” he said as though he were angry about it. “I’ve been teaching for ten years. During that time I have expelled ten students. Do you know why?”

I did, but didn’t dare answer.

“The first person to make fun of my name will repeat sixth grade … No ifs, ands, or buts. Period. You all understand?” We nodded mutely.

“Sit!” he ordered. We dropped down like sandbags.

He sat behind his desk, leaned back, and folded his hands behind his huge bald head. “Today is your last chance for a summer free from school. In my briefcase …” He tapped it with a long wooden pointer. Tap. Tap. Tap. “ … I have exams that will measure your knowledge of English, mathematics, world history, and science. If you

pass all four subjects, you don’t come back until September. If you fail even one, you have me five days a week for six weeks in a row until I mash some knowledge into your empty brains.”

I could not think of one fact I knew for sure about any of those subjects. I peeked at the other students. They looked as sweaty and empty-headed as me.

Mr. Cucumber stood, removed the tests, and placed one face-down on each of our desks. “You will have an hour per section,” he explained, and checked his watch. “The first section is math. Go.”

I turned over my exam. I was sunk right away. I didn’t even get a chance to have some tiny bit of false hope. The first problem was in meters, kilometers, decimeters, grams, and liters. I skipped that problem and leafed through the entire section. It was not multiple choice. I knew right away what I’d be doing for the next six weeks. My head drooped over like a hanged man’s. I asked myself, How many meters of rope does it take to make a noose?

I did all the math I could, then quit. When the hour was up, we had a ten-minute break. I ran to find Betsy.

She was at the water fountain. When she saw me she asked, “How many grams in an ounce?”

I threw up my hands.

“Looks like I’ll have the house to myself while Mom’s away,” she said with supreme confidence.

“Hey, just wait till you get to science,” I said as snottily as I could.

“Already did it,” she sang. “I skipped ahead.”

I felt like an idiot.

At the end of the day the tests were graded before we went home. No one in my group passed.

“If you study, study, study,” said Mr. Cucumber when he called me to his desk, “you might make it.”

I felt doomed.

“One final question,” he asked before I left. “Is a cucumber a vegetable or a tuber or a berry?”

This had to be a trick question. I always thought it was a vegetable. “A tuber,” I guessed.

“It’s going to be a long summer,” he replied and grinned like a rottweiler. He did not look like a vegetarian. He was definitely a meat eater.

When I went outside, Betsy was surrounded by other girls her age. They listened to every word she said. I thought they were going to drop down and kiss her feet.

I squeezed in between her fans. “Guess what,” she said to me and flicked her hair back to look more glamorous. “I did so well I get to skip a grade. And you?”

I had to turn things around. I was going downhill fast. Dad was kicking my butt. Mr. Cucumber was a fiend. Betsy was an instant success at everything. And I was a loser. I really missed Pete. It was his job to be on the bottom of the barrel. Now the entire barrel was sitting on me. I couldn’t get any lower.

“Don’t wait for me,” Betsy said as I dropped my head in shame. “I have a different ride home.”

Great, I thought, as I walked around front. Leave me with the maniac. The way he drives, they’ll soon be hosing my face off the front grille of a tractor-trailer.

When the midget turned into the driveway he headed

for me like a locomotive that had jumped track. The two boys were already bouncing around in the rear like loose packages.

I took the backseat with them and we blasted down the driveway and ran a car off the road when we made our first turn. He hit the gas and I thought of covering his eyes with my hands but didn’t.

Coward, I said to myself. Wimp. Chicken. Yellow-bellied sapsucker! Betsy is more of a man than you are.

We took a turn and nearly hit a goat. After another dozen killer turns we got to the straightaway. The boys desperately yanked down their pants and pulled off their pee bags.

“Give me that,” I said and grabbed the dripping bag out of the younger boy’s hands. I leaned forward and poured it over the maniac’s head. He sputtered and turned around. I was waiting for him with the second bag. Splash! I got him right in the face. He hit the brakes and reached for me. We skidded across the road, hit the curb, bounced up, and slammed into a chain-link fence. It stopped the car like a big steel net. The maniac screamed and hit the floor.

We bounced off the seat. “Come on, boys,” I said. “Follow me.” We crawled out the window as a crowd gathered. I flagged down a cab. “Get in,” I said. They did, and we got stuck in traffic and inched our way down the road along with the other cars, donkeys, goats, and bicycles. The boys just stared at me as if I were the maniac. Ingrates, I thought to myself.

When the taxi dropped me off in front of the house, I paid the driver with money Mom had left me, then swaggered

up the front steps like a big man. Don’t mess with me! I growled and pounded my chest. I’ll pour pee on your head.

It was Sunday. With Mom gone, Dad worked seven days a week. This morning, he was running late and was trotting around his truck. A pipe was sticking out of the overhead rack. It was head-high and just a little bit longer than the truck bed. Each time Dad ran around the truck, getting tools, moving equipment, checking supplies, he ducked under the pipe. He did it without looking, as if it was something he had practiced.

I stood in the kitchen window eating toast and beamed telepathic thoughts at him. As he headed for the pipe, I thought, Duck. He ducked. As he came back around, I thought, Duck. He ducked. Suddenly he snapped his fingers and doubled back to get something he remembered. Don’t duck, I thought.

Bonk! He hit the pipe and his feet went straight out beneath him and he landed flat on his back. I ran down the stairs and knelt over him. I slapped his cheeks back and forth. Not so hard, I warned myself, he might come to in a bad mood. He was breathing but he was out cold. A huge lump popped up on his forehead like in a cartoon. I ran into the house to get some ice. When I came out, he was sitting up with his chin on his knees. He saw me and grinned.

“Wow,” he whistled and shook it off. “That was some sucker punch you hit me with.”

“That wasn’t me,” I said, but I felt guilty for thinking, Don’t duck.

“No kidding,” he replied and hopped up onto his feet, then wiped the dirt off his pants. “You’d have to hit me a hell of a lot harder than that to get rid of your old man.”

He examined himself in the side mirror and combed his hair. He removed his handkerchief and wiped a smudge off his lump.

“See you later,” he said, ducking under the pipe and opening the driver’s side door. “Don’t forget to give BoBo II a flea bath. He smells.”

He pulled away and I strolled around to the front yard. BoBo II wasn’t under the shade tree. “BoBo the Second!” I yelled down the street.

I heard him barking over by Hal Hunt’s garage. I walked over there. Hal had BoBo II trapped in a corner and was throwing bullets at him. He had a box of shells in his hand, and every time he threw one, he jumped up into the air as if the bullet were going to fire and he could skip over it. “Dumb smelly dog,” Hal shouted and threw another bullet. BoBo II looked puzzled. He needed a nap. He was only good for about an hour of energy each day, and his time had expired.

“Hey, what are you doing?” I hollered.

He whipped around and raised his arm over his head. “Watch it, Henry,” he growled. “I’ve got a bullet in my hand.”

“You watch it,” I growled back. “With the power of my mind, I can make that bullet explode between your fingers.” I squinted and touched my fingertips to my forehead. I stared at the bullet and concentrated.

Hal looked at me. I could tell that he wasn’t certain if I was bluffing. I wasn’t sure either. But I had just knocked

Dad cold, so I figured I could set off a bullet. I narrowed my eyes and concentrated so hard I moaned. My muscles knotted up and I began to tremble.

Suddenly he twisted away from my paralyzing mental grip and threw the bullet into the bushes. “You must be a devil,” he cried out and stared into his hand.

“Don’t mess with me,” I said, lowering my hands. “I know where you live and my power is strong enough to cross the street. I can just look at your house and make pictures fall off the walls.” Then I turned to BoBo II. “Come on, smelly,” I said. He followed dutifully.

When Dad came home, Betsy and I sat down to dinner. Marlene served fried chicken, white rice, and spinach. When she left the room, Dad said, “This food is too bland.” He got up and went into the kitchen and returned with a bowl of tiny red peppers. “This will fix it up,” he said. He put a pepper on his plate and passed me the bowl. “Try one.”

“I don’t think so,” I replied.

“You’re chicken,” he said. He hooked his thumbs under his armpits and flapped his elbows up and down. “Bluck, bluck … bluck bluck,” he squawked. “Chicken.”

I hated that. I looked at Betsy.

“Chicken,” she said.

“I am not,” I shot back and put a pepper on my plate. “Anything you can do, I can do, too.”

He grinned. “We’ll see about that,” he said and bit his in half. “Chew it up good,” he instructed and chewed with his mouth open to show me.

I took a bite. My tongue turned into a lava flow of pain.

“Grind the seeds between your teeth,” he said.

I did. The pain increased, but I didn’t twitch.

He finished the remainder of his pepper.

I finished mine. So this is what it’s all about, I thought. Me and Dad. One-on-one. Pepper-to-pepper. This is what Mom meant when she said her leaving would give me and Dad some time to work out the friction between us. But we weren’t going to be equals. One of us was going to end up on top and the other on the bottom.

“Another,” he said.

I took two and chewed them up. The heat spread to my lips and curled violently up into my nose. It was like sniffing battery acid. My eyes watered but my face was so hot the tears probably evaporated.

Dad took two and chewed them. He cracked his knuckles, then settled down and took a bite of chicken. Finally, it was time to eat dinner.

I took a bite of chicken and snorted loudly through my nose. Eating food was like throwing coal into a furnace. Flames shot out my mouth, nose, eyes, and ears.

Betsy laughed. “Your hair is curling,” she cracked.

“Can’t take it, can ya?” Dad asked. “Can’t keep up with your old man? You think you can. But you can’t.”

I closed my eyes and concentrated. Don’t give in, I thought. Don’t.

“I’ll give you a hint,” Dad said. “H … 2 … O.”

I only had milk. “Excuse me,” I whispered. I stood up and went to the kitchen. Once I was out of sight I rolled my head from side to side and let out a silent scream. My breath almost set the curtains on fire. I dove for the sink and stuck my mouth under the spigot and turned the handle.

Oh my God! It was like throwing gasoline on a fire. I yanked my mouth away and almost knocked out my teeth.

I could hear Dad howling with laughter. “Water makes it hotter,” he sang. “Try a piece of bread.”

When I returned to the table he was still snickering. I just kept my eyes glued to the lump on his head.

“You’ve got to get up a lot earlier in the morning to beat me, kiddo,” he said.

I took a bite of rice. It tasted like ashes.

The next morning I was standing on the street corner. Since I no longer was driven to school by the maniac, I had to take the bus. I squinted up at the sun to try and tell what time it was. I couldn’t. It seemed like I had been waiting for a long time, and I didn’t want to be late. Mr. Cucumber was a force to be reckoned with and I wasn’t feeling very chipper. After dinner it had taken a long time for my stomach to cool down. I had spent half the night tossing and turning in bed.

“I need a watch,” I said. No sooner had I said it than I spotted one lying on the side of the road. It was tilted at just the right angle, so that the sun bounced off the crystal and hit me in the eye. “Seek and ye shall find,” I said. I was definitely becoming more powerful. Nothing could stand in my way. The pepper contest with Dad was just a little setback.

I picked the watch up and put it on. It was even set at the right time. I snapped my fingers. “Bus, arrive!” I shouted. In a second, the bus turned the corner and stopped in front of me. Not a bad beginning to a new day, I thought. I needed a boost.

After about an hour of Mr. Cucumber telling us how useless we were, my attention wandered to my new watch. Since I was sitting near the window, I moved my wrist so that the sun hit the crystal. I followed the angle and spotted a little patch of bright light on the far wall. Mr. Cucumber drifted in my direction, so I gazed up at him as though I were really listening. When he turned away, I adjusted the crystal so that I shot a sharp laser beam of light into the corner of his eye. With each blast I gave him, I concentrated on two words, migraine headache.

I had zapped him a couple good ones when he suddenly whipped around and aimed his pointer at my nose. “Do you think I’m an idiot?” he shouted, and bore down on me. He drove the pointer into my chest like a short, fat, bald, cucumber Musketeer.

I was struck dumb.

“Take the stick,” he commanded. His face was as tough and scuffed up as the toe of an old shoe. “Take it!”

I pulled it away from my chest.

“Give me your wrist!”

I held it out to him.

He unlatched the watch and set it down on my desk. “Stand up!”

I stood.

“Lash it!” he shouted.

“What?” I asked meekly.

“The watch. Lash it!”

Well, easy come, easy go, I thought. I brought the stick down and hit it squarely. Nothing broke.

“Again! Harder!”

I hit it again. And again. And again. I used both hands

and brought the stick down with all my might. Crack! The crystal shattered. The hands and face flew off. Then all the little gears exploded apart.

“Enough!” he said, and snatched the pointer in midair. “Now pick all that up, sit down, and never pull a stunt like that a second time.”

I sat there. The other kids stared at me as I felt my power go down the drain. One kid unlatched his watch and quietly slid it into his pocket.

I took the bus home and got off early at an open field where there was a giant tamarind tree. I loved the tangy flavor of tamarinds and thought they would be strong enough to replace the burnt taste in my mouth still left over from dinner the night before.

I searched the ground. None had fallen from the tree. I picked up some rocks, looked around for houses, then threw them at the pods. A few dropped down. They were still a bit green, but I craved that sour taste. I sat with my back against the tree and ate a bunch of them until it felt like my face had curled inside out.

Down the street I stopped and drank from a public tap. The water was so cold and sweet. My mouth didn’t burn and it felt good to drink water again. I drank until my belly swelled out.

There was nothing else to do but go home. It was a long uphill walk and I took my time. The sun was out and I was sweating and suddenly my stomach began to roll around. I thought maybe I would have to burp, but it wasn’t that. I could feel bits of leftover peppers and green tamarinds and water mixing together like something fizzy and powerful.

But it didn’t fizz up. I could feel it moving lower in my stomach, spinning around and around like something being flushed down a toilet. I began to walk faster. My legs felt tired. My knees were wobbly. And then I got the first hint of a loose feeling in my butt.

Oh no, I thought. The house was still two streets away. There wasn’t a bathroom until I could get home. I walked faster. When I passed Shiva’s house, he yelled out at me. “Hey. Do you want to go running?”

I didn’t even slow down. I was concentrating on keeping my butt as tight as possible. I couldn’t even shout back. I thought that if I yelled out, I’d lose control of my rear end.

“No,” I squeaked. “Gotta go.”

“You look a little sluggish,” he yelled. “Want some prunes?”

I shook my head no.

“Well, I don’t want to practice with you anymore.”

I couldn’t even apologize. I kept moving.

“What goes around, comes around,” he said. “Think about it.”

I was trying not to.

My book bag felt like it weighed a ton. I hiked up the street. My stomach rumbled. Concentrate, I told myself. You can do it.

I had one more street to go. I heard a car coming up behind me. It honked but I wasn’t going to get out of its way. I just waved my arm for it to pass around me. As the driver swung by, he shot me a dirty look.

Don’t mess with me, I thought to myself. I’ll pour pee on you. But just the thought of pee made my bottom feel weaker.

I picked up speed. I balled my hands into fists of steel. I squinted. I bit my pepper-blistered lip. But the feeling in my gut grew worse, and lower. My butt began to quiver. I can make it. I can make it. I can make it, I thought over and over. My face was all pulled together and my rear end was so tight I walked like one of those speed walkers with my butt drawn in and my arms and legs swinging wildly for maximum forward momentum.

And then it happened. My legs got spastic, and when I tried to step around a broken bottle, I stubbed my toe and lost concentration. Whoosh! The dam broke and I felt it running through my underwear and down my shorts and down the backs of my legs. I moaned and started to run.

Hal Hunt was standing by his mailbox as I sloshed by.

“What happened to you?” he yelled. Then the smell hit him. “Ugh!” he hollered. “You smell worse than your dog.”

I ran past our front gate. I couldn’t go into the house. Betsy would crush me. I ran down the driveway toward the laundry room. There was a little bathroom back there. Whoosh! It hit me again. I was frantic. I opened the bathroom door. I kicked off my shoes and pulled down my pants. I slid down onto the seat and leaned forward with my head on my knees. Whoosh!

“What power?” I groaned to myself, and slapped at the flies that settled on my ears. “I don’t stand a chance.”