The house kept stinking of natural gas. Dad had checked the pilot lights on the stove and the pipe connections running from the stove to the big silver tank out back. But he could not locate a leak. It was especially strong in the afternoon. We sniffed around like bloodhounds but only found decaying bugs, mold in the corners, and bits of cruddy food under the refrigerator.

One day it was especially bad and Mom was worried that if Dad lit a cigarette the house would explode like a tanker truck, so she made him smoke out on the front porch, while she turned on all the ceiling fans. He grumbled about being booted outside, but he went, which to me meant that he thought there was something seriously wrong.

“I just want to warn you about one thing,” Dad said, sitting back in his porch chair and blowing smoke rings up

toward the light fixture. “A house filled with gas can be set off in a lot of ways. You don’t need a match to blow up this place. The way it happens is simple. Suppose the house is filled with gas and you come home. What’s the first thing you do?”

I tried hard to come up with the right answer. “When I come home,” I answered shakily, “I open the door.”

Dad nodded. “What’s the next thing you do?”

“I turn on the lights,” I replied.

“And the next?”

“I walk down to the kitchen.”

“Next?”

“I turn on the ceiling fan.”

Dad leaned forward and dropped his cigarette into his empty beer can and shook it around. “You’d be dead at least three different times,” he said, holding up three fingers. “First, as soon as you turn on the lights, the spark from the switch would set the place off. Kaboom! But let’s say you didn’t turn on the lights. So, you walk down the hall. The little metal cleats or nails on the bottom of your shoe might give off a spark on the terrazzo floor and kaboom! you are dead again. But let’s say you were wearing sneakers. Then when you turned on the fan, kaboom! Switching on any electrical appliance gives off a spark, and you are burnt toast.”

“Can I use a flashlight?” I asked. I wanted to read at night without blowing myself up.

“Yeah, a flashlight is okay. Just don’t drop it and break the little bulb, because the red-hot filament would set off the gas.”

“What if the fillings in my teeth rubbed together in my sleep and made a spark?” I asked.

“Don’t get carried away,” he said, and lit another cigarette. He exhaled slowly as though he were leaking like a broken gas pipe.

Betsy was the one who solved the mystery. She walked into the kitchen a few days later and caught the new babysitter, Missy, sliding Eric into the unlit oven. She had him in a big turkey-roasting pan while the gas was turned up full-blast. It was time for his afternoon nap and she was gassing him to sleep. “Breathe deeply,” Missy whispered. “For a deep, deep, deep sleep.”

Betsy screamed. Missy jumped back. “I’m not doin’ anything wrong,” she squealed. “It’s just a little gas.”

Betsy snatched Eric off the oven rack. “Wait till my mother gets her hands on you,” she said with authority. “She’ll have you thrown in jail.”

Missy turned and ran out the kitchen door and up the driveway and down the road toward the bus stop.

When Mom came home Betsy blurted out the story. “I was so angry,” she said, “if I’d had a gun I’d have shot her.”

Mom was horrified. “Eric may have brain damage,” she cried, holding him close to her face and kissing his forehead. She pressed his little belly and smelled his mouth and nose for gas. Maybe she thought he was filled with gas and if she let him go he’d float up to the ceiling like a hot-air balloon.

“Oh, he’s okay,” Dad remarked, making light of her

concern as he jingled the change in his pocket. “He’s one of our kids, so he’s brain-damaged already.”

Mom managed a strained smile. “I’ll call the doctor tomorrow,” she said.

“Don’t you think we should call the police?” Betsy asked. “What she did was like a Nazi war crime.”

“It would just be your word against hers,” Dad replied. “If anything should be done, I’ll do it myself. Do you know where she lives?”

We didn’t answer.

“Well,” Mom said, “let’s not get mixed up in it. Let’s just be happy that we’re all fine.”

But Dad did not feel fine after Stumpy Hill’s house was robbed. They lived four houses down the street. A police inspector came by to ask if we had seen or heard anything peculiar the night before. I stood behind Dad when he answered the door. The inspector’s uniform was gray with red piping and he wore an officer’s cap with a gold police badge fastened above the visor.

“We don’t know a thing,” Dad replied to his question. “Didn’t hear anything. Didn’t see anything.”

“May I have a glass of water?” the inspector asked.

“I’ll get it,” I said, and dashed back to the kitchen. When I returned, the inspector had taken a seat on the porch and was casually telling Dad the story.

The robber had removed the small jalousie windows over the stove and crawled in. He went to the bathroom and tied a hand towel across his face. He went into the kitchen searching for money and removed a dinner knife from a drawer. Mrs. Hill was having a sinus spell and got

up to get a tissue from the bathroom. When she returned to the bedroom, the robber was going through the dresser drawers. She screamed. He turned on her and tried to hold a pillow over her face. They wrestled. He tried to slash her, but she held his wrist and pushed him back against the chif forobe. Stumpy finally woke up and joined in. Mrs. Hill was worried about him, as he had recently had a heart attack and he was panting real hard. The thief had Stumpy pinned on the floor, so Mrs. Hill yelled out, “What do you want?”

“Money,” the thief replied.

She got her purse, but before she could reach in and remove her wallet, he snatched the purse and ran out the front door, vaulted over the porch wall, and vanished. After he left, Stumpy discovered that his fingers had been sliced from struggling with the knife.

The police had already found a bloody hand towel up at the corner. That’s why they were asking everybody in the neighborhood if they had seen or heard anything suspicious.

“No,” Dad repeated. “We didn’t hear or see a thing.”

The inspector finished his water and stood up. He reached into his uniform pocket and removed a business card. “If anything comes to mind,” he said firmly, “give me a call. My name is Inspector Grander.”

After he left, Dad went into his office and made several telephone calls.

The next evening he came home late from work and called us into the dining room. He unwrapped a large package and removed two pistols.

“This one is for you,” he said to Mom. “It’s a .25 caliber revolver. And this one is for me. It’s a .38.”

I stared at them and stepped back. They were blue-block and big as a pair of crows. It was as though he had unwrapped something horrifying, like a human heart or severed hands. It scared me to look at them. He picked up the .38 and pointed it at the wall over our heads. I ducked down. It was the same as watching a horror movie that was too frightening. When I hid behind the seat in front of me, I had a moment of relief, but then curiosity got the best of me and I always popped up just in time to catch something brutal and bloody explode in Technicolor across the screen.

When I lifted my head again, Dad was putting the gun into Pete’s hands. I ducked again.

“Cool,” Pete said. He waved it around.

Dad snatched it away from him. “It’s not a toy,” he said. “It’s something to be respected even when it’s not loaded.”

“I’d rather not take the law into our own hands,” Betsy said and shook her head in disapproval. “Remember, those who live by the sword die by the sword.”

“I, for one, will sleep a lot easier with these in the house,” Dad replied and thumped himself on the chest. “And I bet Stumpy Hill wishes he had one the other night.”

Mom looked doubtful. “These things lead to accidents,” she said. “I just don’t think they are safe.”

“The only reason to be afraid of a firearm is if you don’t know how to use it,” Dad insisted. “So I’ll give you lessons. I just want to protect the kids.”

“I’ve never fired a pistol before, just rifles,” she said, sounding like she’d give it a chance.

“There’s nothing to it,” Dad replied knowingly. “You just point and shoot.”

After the sun went down, Mom and Dad drove out to the horse track. The racing season was over and the track was the biggest stretch of flatland where Dad could let Mom shoot at things.

When she came home, she didn’t seem so concerned about having guns in the house. “Not bad,” she said. “I pointed it into the night and fired a few shots. It was more like firecrackers going off.”

“Did you hit anything?” I asked.

“Couldn’t tell,” she replied, as she unpinned her hair. “It was too dark.”

The next morning I woke up when Mom screamed, “Oh my Godl”

I jumped out of bed and ran into the hall, where I bumped into Pete and Betsy as we raced into the dining room. Mom was standing with her hands pressed over her mouth. She seemed frozen.

Dad was standing next to her. He rubbed her shoulders and hugged her from behind. “It means nothing,” he insisted.

“What means nothing?” Betsy demanded.

Dad pointed at the newspaper headline. It read MAN FOUND SHOT DEAD AT RACETRACK.

“But it wasn’t her,” Dad said.

“What would happen if it was?” she replied.

“We’d have to sneak her out of the country,” said Dad. He seemed to have already considered the possibility.

“We’d put her on a local cargo ship and send her to Brazil.”

“Brazil?” I exclaimed. “Why?”

Pete was so frightened I pulled him to my side and let him hang on my arm.

“We have relatives in Rio,” Dad replied, without skipping a beat.

“Really?” Betsy asked.

We had never heard about them before. I thought everyone I was related to lived in Pennsylvania.

“Yeah,” Dad said. “My uncle’s sister and her family went there years ago. We could put Mom up with them.”

Mom looked at Dad and shook her head. “We’ve never even seen them, written them, talked to them, even heard of them before this moment, and you want me to go hide there like a common criminal? Have you lost your mind?”

“Do you have a better idea?” he asked.

“Yes I do,” she replied directly. “I can call up the police and tell them that I may have accidentally shot that poor man.”

“Wait,” Betsy said, holding her hands out like a traffic cop to control the conversation. “One thing at a time. Tell me more about our relatives.”

“They’re rich,” Dad said. “They own half of Rio. They married a bunch of Syrian lawyers and merchants and have a fortune.”

Just then Eric began to cry. Betsy trotted up the hall. She returned with him pressed against her shoulder.

“Let’s get back to Mom,” I said. “I’m worried.”

“Don’t get too upset,” Mom replied. “I’ll just wear a

fake beard and mustache and fly back home and live in a barn with Uncle Jackson’s chickens.”

“Hey, let’s get to the real point,” Dad said. “Accidental shootings happen all the time.” He snapped his fingers. At that very moment some poor guy was just walking down the street somewhere and wham! he was a goner.

“Once,” Dad continued, “on New Year’s Eve, Gooz Youski went out to his back porch and fired off a clip from his deer rifle. The next day they found some unlucky guy in the woods near Hecla shot dead with a deer slug. Same-caliber bullet. We figured it was Gooz, but nobody said anything. It was an accident. Couldn’t reverse what had happened so why make it worse by sending Gooz to the slammer. Besides, we were all a little impressed with Gooz, because he had never hit a moving target before in his life.” Dad smiled at his last remark. We were supposed to smile along with him but didn’t.

“Well, I’m no Gooz Youski,” Mom said, growing angrier and twisting out of his grip. “If I shot that poor man, I’ll pay the price. I never should have let those guns into this house in the first place. I knew they would lead to trouble.”

“Hey, it’s not the gun’s fault,” Dad quickly replied.

“You’re right,” Mom snapped back. “It’s my fault, pure and simple.” She picked up her coffee cup and marched down the hall.

Dad raised his voice so she could still hear him. “Well, it would just be a manslaughter charge at best,” he said. “You couldn’t get much time for an accident. Maybe a year or two.

Mom stomped back up the hall and pointed her finger across the table at Dad. I was glad she didn’t have her gun just then. She was furious. “Mister,” she said sternly, “someone shot and killed an innocent man and it might have been me. These children,” she said, and pointed at us, “may lose their mother because she listened to you. Now don’t make light of this. It’s serious.”

Dad gazed up at the ceiling and waved his hand in front of his face like he was shooing a fly. “No big deal,” he maintained. “You’re making a mountain out of a molehill. You’ll see.”

Mom went into the bedroom. When she came out, we were still standing around the table like wax figures. “I just called Inspector Grantley,” she announced. “He said he would be right over.”

“I wish you wouldn’t get mixed up in this,” Dad pleaded. “You didn’t shoot that guy. He could have been shot by anyone.”

“Well, let’s all get dressed,” Mom said. “We don’t want to look like a bunch of criminals when the police arrive.”

We were waiting on the front porch when Dad turned to Mom and asked, “Where is the pistol? The cops will need to examine it.”

“I threw it down the well in the back yard,” she replied and turned away from him as she snapped a dead flower off a hibiscus plant.

“That only makes you look more guilty,” he said and folded his hands over his head.

“I don’t know if I’m guilty,” she replied. “I’m scared. I just threw it down the well because I didn’t want to see it

anymore. And while we’re on the subject, where is your pistol?”

“In my sock drawer.”

“That’s not much of a hiding place,” she said.

“Hey,” he replied. “I’m not the one who has something to hide.”

Just then Inspector Grantley and his driver pulled up in front of the house. The inspector opened his door and when he stood up he stared across the roof of the car. We were all gathered on the porch, staring directly back at him. If we were in a movie, that would be the moment for a big bloody shoot-out between the Henry gang and the cops.

He walked through the gate and briskly climbed the stairs. Dad shook his hand and said, “Hell, she couldn’t have shot that man. She can’t hit the broad side of a barn from ten feet away.”

Inspector Grantley did not seem convinced. “We’ll see,” he replied dryly.

He was more interested in Mom. “Where is the gun?” he asked.

She told him.

“I’ll send some men around to fetch it,” he said. Then he held his arm out as though he were going to ask her for a dance. “I’ll have to take you down to headquarters,” he said softly. “If you have a solicitor, you should call him.”

Mom turned toward us with a brave face. “There is nothing to worry about. I want you to clean up your rooms. Do your homework, and if you go out to play, be home in time for dinner.”

“Yes, Mom,” we all murmured. We were teetering like three bowling pins about to fall over.

Then she reached for Dad’s hand. He seemed to be momentarily stunned. “Aren’t you coming?” she asked. He snapped to attention and led her down the steps.

Soon after they left, another carful of police arrived. I showed them where the well was in the back yard, and sat on the porch steps and waited. I didn’t warn them about the bats. When one of them took a sledgehammer and hit the cement patch to widen the brick-sized hole, a tornado of bats rose up. The men bellowed and jumped back, with their faces crumpled in fear. It felt very good to watch them cower, because I imagined, at that moment, other police were scaring Mom.

In an instant the bats disappeared and the cops began to relax and laugh at themselves. I laughed along with them. Finally, they smashed open the hole and lowered a long pole with a wire basket on the end. After a few scoops through the muck, they pulled up the pistol and shook it out of the basket and into a plastic bag.

They turned and walked away, teasing each other, with their arms held over their heads like giant bats. I watched them and thought of the moment Dad brought the gun into the house. “Nothing but trouble,” I said to myself.

At the end of the driveway stood Hal Hunt. He was snooping around because he had seen the police car.

“What are you spying on?” I hollered and threw a rock at him. He ducked and ran back to his yard. “Mind your own business” I yelled.

When Mom returned in the afternoon, she showed us the black ink on her fingertips.

“Did you kill him, Mom?” Pete asked.

“I wish I knew, honey,” she said, sighing. “But I don’t.”

“What’d they make you do?” I asked.

“Really, I just told my story to different inspectors and sat around drinking coffee until they took my fingerprints and sent me home.”

“Well, when will they tell you for sure?” I pressed.

“I don’t know that either,” she replied. She looked more tired than worried. “I’m going to take a nap,” she said. “It’s been a heck of a day.”

I thought if Mom went to prison I would make her a diary with a special lock and key. But it would be a trick key and she could use it to open her cell and escape. I’d meet her outside the prison and we could take a cab to the docks, untie a sailboat, and take off south for Brazil. We’d just sail right up onto the beach at Rio, call our relatives from a phone booth, and live with them. When things cooled down, we would send for the rest.

Just then Betsy opened my door. “Look,” she said. “I’ve been thinking. If you were any man at all, you would tell the police you shot the pistol. They can’t throw a kid in jail. They’ll just slap you on the wrist and let you go. But they might put Mom in jail, and then what would happen to us?”

“You’d have to be the mother,” I replied.

“Just think about that I” she said. “But seriously, what about taking the blame?”

“I can’t,” I said. “They’d know.”

She looked me up and down. “You’d rather let your own mother go to prison than save her.”

“That’s not true,” I replied. “I’m working on my own plan.”

“What’s that?”

“I can’t tell you,” I said. “I haven’t figured out the details.” I wasn’t sure how big a prison key was in comparison with a diary key.

“Coward,” she snapped and closed the door.

I did feel like a coward. Suddenly the diary idea seemed childish. I had to think of something else. Something that would work.

The following day Dad was still at a job when the squad car pulled up.

“Mom,” I yelled and ran to the front porch.

Betsy followed. “I guess Mom did it,” she said to me. “They’re coming to take her away. Now’s your chance to save her, unless you are as spineless as I think you are. Hurry. Throw yourself at his feet and beg for mercy.”

“You do it,” I shot back. “They know it was a woman who pulled the trigger.”

She pinched the skin just above my hips. “Idiot,” she cracked. “I’m the only girl in the family. If you got sent to prison, there would still be two boys left over.”

“You’re full of it,” I replied and slapped her hand away.

“And another thing,” she said quickly as Inspector Grantley opened his car door. “If I got sent away, this family would collapse.”

Mom arrived and stood between us with her arms around our shoulders. From behind, Pete squeezed his head between our waists.

Then Inspector Grantley gave a wave of his hand and tipped his hat as he got out of the squad car, just so Mom could see his friendliness meant good news. I liked him just for that alone.

Mom exhaled and her arm felt heavy across my shoulder. I looked up at her face and caught her rubbing her eyes against the shoulder of her shirtdress.

The inspector climbed the stairs and extended his hand. “You are no longer a suspect,” he said politely.

“Thank you,” she said and removed her arm from my shoulder to extend her hand to his.

With his other hand he held out a small brown bag. “I’m returning your pistol. Please, don’t fire it in public places,” he reprimanded.

“Don’t worry,” she assured him. “It will never be fired again as far as I’m concerned.”

Betsy stepped forward. “Well, who shot the man?” she asked.

“It was a family quarrel,” he replied softly.

When the inspector left, Betsy tried to talk Mom into suing the police. Mom said she would do no such thing and sent her and Pete up to the corner store to buy formula for Eric.

As soon as they were gone she called me into her bedroom. She opened Dad’s sock drawer, pulled out the .38, and lowered it into the brown bag.

“We have to throw these away,” she said secretively. “Some place where your Dad can’t find them.”

“Okay,” I replied. “But you’ll have to drive.”

“Honey,” she said and gently touched my face, “me driving

is more dangerous than me shooting a gun. Besides, you have to do it alone. Betsy and Pete will be back any minute and I have to stay with the baby. I’ll call a cab.”

I didn’t want to do it alone, but I didn’t want to be spineless either. It was my chance to save all of us from having guns in the house. “Where should I hide them?” I asked.

She opened her wallet and gave me twenty dollars. “You pick a spot,” she replied. “But don’t tell me where. It will have to be your secret.”

I took the cab out to Needham’s Point and walked out to the end of the jetty. I felt like someone was looking over my shoulder, especially with the tall lighthouse just behind me. I turned around and didn’t see anyone. I could feel how angry Dad would be if he knew what I was up to. Even though he didn’t know where I was or what I was doing, I knew he would soon want to know the answer to both those questions. He got upset when he found a tool out of place. He’d definitely be on a rampage when he found his gun missing.

It was dusk and the sky was more purple than orange. The waves foamed up over the ring of coral reefs just off the point. I set the bag down, reached in, and removed the .25. I stood up and winged it out there as if it were a flat rock. It hit the blue water and sank without a splash. I grabbed the .38. It was heavier. I reared back and threw it overhand. It splashed like a fish jumping. I bent down and picked up a rock and threw that, too, then another and another, as though I had been throwing rocks all along. Then I turned and quickly walked past the lighthouse, then up the road to Bay Street, where I flagged down a cab. I

sat quietly in the backseat and thought, If anyone asks, I’ll tell them I was throwing away my diaries so no one would read my secrets. I asked the driver to drop me off on the corner, so I could walk home as though I had been out playing.

I entered through the back door. Mom saw me before I could get to my room. “He’ll be home soon,” she said and kissed me on the head. “He’ll be mad, but he’ll get over it. Don’t worry, I’ll take care of you.”

I nodded. I was scared speechless. Would she take care of me before or after he got to me?

Just then Dad’s tires skidded to a stop as he pulled into the driveway. The door slammed behind him.

“See,” he called happily after bounding up the stairs. “I told you you couldn’t hit the broad side of a barn.”

“Don’t make a joke of this,” Mom replied. “I’m still upset.”

Dad picked her up by the waist and swung her around. “Let’s go celebrate,” he said. “We’ll drive out to the Sandy Lane for lobsters.”

“Oh, that would be lovely,” Mom replied. She gave him a long kiss. “I’ve had a rough day.”

“Then let’s get a move on,” he cried, and headed for the bedroom.

This is it, I thought. When he gets dressed he’s going to go into his sock drawer. I walked down to my bedroom to wait.

I sat on my bed and timed it. He undressed. Showered. Dried off. Shaved. Opened the underwear drawer. Closed it. Opened the sock drawer.

“Where is it?” came the shout through the wall.

“I got rid of it,” she said defiantly, standing up to him.

“Did you throw it in the well?”

“You told me I was stupid for doing that the first time,” she said. “You’ll never find it this time. Never in a million years.”

He finished dressing and in a few minutes he was in my room, standing with his hand on his hip. He put his other foot up on the edge of my desk chair and tapped his fingers on the top of his knee. Betsy was right. It was my job to save Mom. But who was going to save me? If there was one less boy in the house, they would still have a family.

“You know where they are,” he said. I jerked away from his eyes, but in a glance he knew that I knew something about the guns.

“Yes,” I replied.

He waited for me to tell him. But I didn’t.

“Your mother will tell me anyway,” he said.

“She doesn’t know where they are,” I replied. Then added, “We’re all afraid of them.”

“That’s nonsense. Now, you know,” he said tartly, “I’ll never be able to trust you again if you don’t tell me.”

I didn’t say anything.

“I’d like to trust you,” he repeated. “But you’re making it hard for me.” He shrugged and suddenly looked disinterested.

I thought he was going to be angry, but it was more like he was willing to give up on me, as if it didn’t even matter whether he trusted me or not, when trusting a person is one of the things that matters most in life.

I stood there thinking, He’s taking her to dinner and I’m taking the blame. That’s not the same as saving Mom. It’s

more like letting her off the hook while she’s feeding me to the wolves.

“I guess you are more like your mother,” he said.

“I hope not,” I replied.

Mom opened the door and stuck her head in. “I’m all ready,” she announced.

“One minute,” he replied. She closed the door. He just shook his head and slowly stepped back a few paces. Then he crouched down and held his hand on his hip like a cartoon gunslinger. I recognized the pose. We used to play “Showdown” when I was a little kid, when shooting each other full of lead was just a game.

“Get ready to defend yourself,” he drawled out in a cowboy voice.

I backed away from him with my eyes on his eyes, my hand hovering over my hip. My fingers twitched.

“Draw!” he shouted as his hand came up. He pointed his finger at me and fired as I dove for cover and tumbled across the bed. I tried to draw my six-shooter but he fired again. He missed as I rolled off the bed and into the thin space between the mattress and the wall.

“I missed you this time,” he growled in a varmint voice and blew smoke from his fingertip. “But I’ll be gunnin’ for you.”

I was going to pop back up and ambush him, but he turned off the overhead light and slipped out the door. The game was over.

In a moment Mom opened the door again. “Jack,” she called, in her concerned voice, “are you in here?”

I didn’t answer. I stayed crouched behind the bed. I did my part, I thought. You do yours.

“Let’s go,” Dad hollered from the living room. “I’m hungry.”

“I promise there won’t be any more guns,” she whispered and closed the door. I didn’t move until I heard the car start. Then I crawled back on the bed. I stood and jumped up and down on the mattress. The springs creaked as I got higher and higher. I reached out in the darkness and touched the ceiling with the palms of my hands.

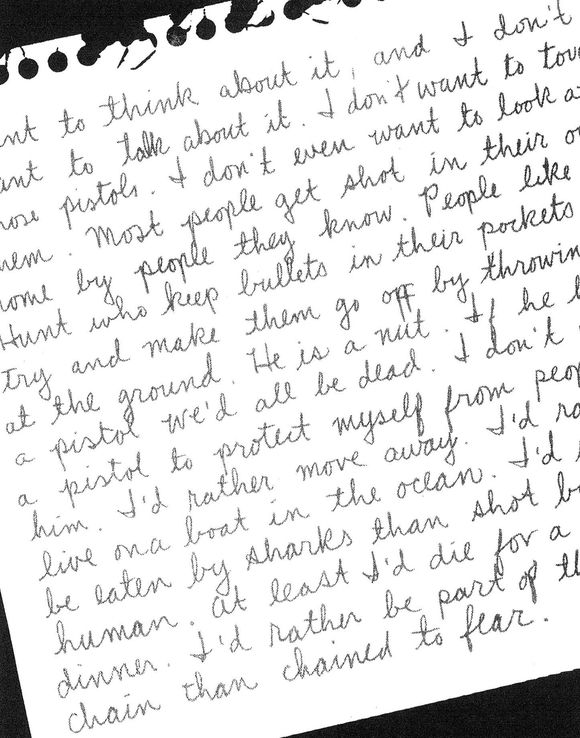

“I’m thirteen years old now,” I said. “I bet I live to be a hundred. That’s eighty-seven more years of dodging bullets.”