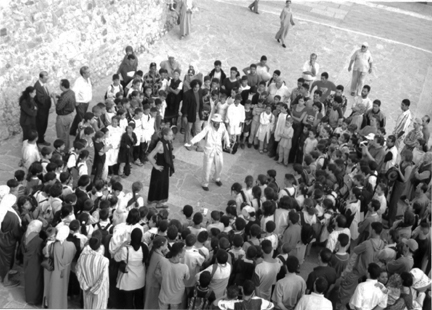

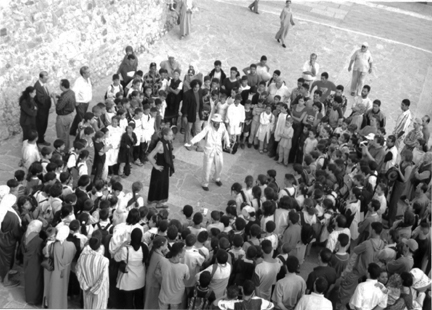

Figure 1.1 Audience in a circle called halqa in Arabic theatre. Courtesy of Khalid Amine.

Marvin Carlson

The original inspiration for this chapter was an invitation to speak at a conference held in Berlin, Germany, in October 2009 on the politics of space: theatre and topology. I was delighted when I learned the venue for the conference, the recently established Institute for Cultural Inquiry, better known as ici Berlin. What fascinated me was the fact that the institute logo, normally printed in lowercase letters, encouraged another reading—the French word “ici,” so that in French the logo reads “Here. Berlin.” What, it seemed to me, could be more appropriate for that conference than to meet “here,” ici, to consider some of the fascinating implications of the particular kinds of here-ness involved in theatrical production and performance.

This fortuitous appellation was far from the only reason why the Institute for Cultural Inquiry was particularly well suited for such a conference. Its mission statement emphasizes three aspects of culture that it takes as its central concerns, and one of the three is in fact space (the other two being identity and discourse). It is clear that the organizers of the institute took this aspect of their project seriously by the attention given to spatial meanings and spatial politics in the introduction to the institute posted on its website. I quote the relevant paragraph:

The ICI chose and designed its location and architecture specifically in view of its mission. Berlin with its complex history, its experience of division, its dynamic and multilayered present and its high concentration of cultural, academic and creative activity is a particularly well-suited place for the ICI. The Institute is situated in Prenzlauer Berg on the border to Berlin-Mitte within the Pfefferberg complex, a former brewery developing into a vibrant cultural and social centre. The facilitation of a broad range of intellectual and cultural interactions was also a central concern of the institute's architectural design.1

I could spend most of this chapter exploring the implications of this fascinating paragraph but will note here only the two most closely tied to theatre and topology, first the urban location, here noted in the evocation of Prenzlauer Berg and Berlin-Mitte, two geographical locations with, as the statement suggests, a deeply rich layering of meanings and associations— artistic, historical, cultural, and political—and second, the noting of the building itself as a recycled space, an essential feature of much modern theatre and architecture—with the inevitable laying of associations that that process also involves. Indeed the phrase “a former brewery developing into a vibrant cultural and social center” ties the ici into a major network of enterprises around the world tied together not only by common cultural concerns but by a particular spatial dynamic with major implications for their role in the contemporary city. Both the analysis of urban space and the dynamics of physical location are of central concern in current theatre and performance studies.

The name “ici” evokes other associations as well. Perhaps most importantly, it can serve to call our attention to a particular quality of space in the theatre, the importance of presence, what we might call “here-ness” of the operations of theatre. This “here-ness” is fundamental both to the particular kind of fiction with which the theatre is involved and, equally important, with the particular way in which that faction is experienced by its audience. I would like to briefly to consider the way each of these operate in this art form. In an often-quoted theoretical statement about drama by Thornton Wilder, titled “Some Thoughts on Playwriting,” Wilder proposes four “fundamental conditions of the drama,” which he claims separates it from the other arts. None of these is directly concerned with space, although the second—that the theatre is addressed to a group mind—does note that a play requires a crowd. This, of course, could have led Wilder into speculations about the space in turn required by this crowd, but he goes in a quite different direction, considering what sort of material appeals to a crowd rather than an individual. His fourth fundamental condition, however, considers space's traditional partner in the ordering of reality: time. Theatre, he observes, takes place in a perpetual present time. “On the stage it is always now.”2

A number of features in Wilder's important article place it in its own historical period (it was published in 1941), but one of special interest to us is that he is writing before what has been sometimes called a “spatial” turn in theatre aesthetics. This involves many aspects of the discipline, among them a move away from a focus on linear structure and a narratology of temporality. Were Wilder writing today he might well add that the drama also takes place in a perpetual present space. “On the stage it is always here.” Indeed it is a rare play that does not begin with a stage direction indicating what that “here” is for this particular action, whether it is as elaborate as a Shavian parlor or as simple as Beckett's famous “A country road. A tree.”

A look backward from this new spatial awareness to the more traditional linear one confronted me as I sought to convert my convention presentation, centrally involved with the multidimensional here-and-now relationship with its audience, to the more abstract linear form of the printed essay.

Although I can still use the word “here,” it is no longer the real shared space of the theatre or the conference room, but the conventional and shifting space of the literary imaginary. My own “here,” an office in central Manhattan, is far different from your personal “here,” dear reader, which I am unable even to imagine, let alone to share.

This disturbing distance imposed upon our “here-ness” by the intervention of writing has become central to modern performance theory, especially in its discussions of the phenomenon of presence, but it has occasionally been a matter of concern in the past. One of my favorite examples is the haunting little poem by Keats, “This Living Hand.”

This living hand, now warm and capable

Of earnest grasping, would, if it were cold

And in the icy silence of the tomb,

So haunt thy days and chill thy dreaming nights

That thou wouldst wish thine own heart dry of blood

So in my veins red life might stream again,

And thou be conscience-calmed—see here it is—

I hold it towards you.3

The chilling effect of this masterful little work is centered of course, on the word “here,” when the dead hand of the poet, living in his own “here,” stretches uncannily out through his words into our own “here,” to haunt and chill. The deathly distance imposed by the written as opposed to the spoken “here” has surely never been so powerfully expressed.

Only occasionally has the theatre mounted a challenge to this central quality of physical presence. One famous iconoclastic drama in the early days of the modern theatre challenged “here-ness,” as it did much of the apparatus of the conventional theatre. When Alfred Jarry's Ubu roi was given its famous premiere performance at the Théâtre de l'Oeuvre on December 10, 1896, it was preceded by a prologue, delivered by the author, which ended with the striking and highly unconventional observation: “As to the action, which is about to begin, it takes place in Poland, which is to say nowhere.”4 Of course this amusing literary device by no means removes the “here” of the ensuing action, which takes place within its clearly defined imaginary world, including Père Ubu's chambers, the royal palace, and so on, like the most conventional drama. The evocation of Poland adds a complex further dimension to the situation. The clear reference is to the disappearance of Poland as a political entity, a process that had begun with the partition of that country among Prussia, Russia, and Austria a century before and had been completed by the mid-nineteenth century. Jarry and his audience well knew, however, that this was by no means the end of the matter. Paris was a favored location for Polish exiles, passionately dedicated to the restoration of their country, a goal achieved in the new century. Although this political background has little direct bearing on the action of Ubu, it serves as a reminder that the imaginative “here” of the theatre stage can draw upon the entire experience, memory, and fancies of its public to create a present space of potentially infinite variety and complexity.

Theatre as an artistic and cultural activity has been the subject of academic speculation ever since the Greeks, but it was not until the beginning of the nineteenth century that European and American scholars institutionalized a field of theatre studies. A significant part of this new field's self-definition involved a clear splitting away from traditional literary studies, within which theatre had previously had its academic home, and this split was centrally concerned with a new attention to space. The entire Western tradition, from the Greeks onward, considered the drama primarily as a branch of literature (the other basic divisions being the epic and the lyric). Traditionally, theatre scholarship was based upon the literary text (Aristotle's indifference to spectacle is an early and notorious example of this bias), and the actual process of the physical realization of this text, while not entirely ignored, was a matter of considerably less interest.

Two pioneering theatre scholars presented a radical challenge to this orientation at the turn of the nineteenth century: Brander Matthews in the United States and Max Herrmann in Germany. Their new perspective, which was bitterly resisted by many of their colleagues in both countries, was not to reject the study of literary drama but to insist that such study was incomplete unless one went beyond the literary text to consider the physical conditions of performance, the spatial realization of that text. Thus it is no exaggeration to say that the foundation of modern theatre studies was grounded upon a spatial reorientation—from the linear reading of drama to the three-dimensional staging of it. Herrmann was particularly interested in audiences and what would later be called reception theory, while Matthews, who in 1899 was named at Columbia the first professor of dramatic literature in an English-speaking university, was more particularly interested in a spatial concern: the shape of historic theatres and the relation of that space to the plays presented in them. In his 1910 A Study of the Drama, he stated this fundamental principle in these terms: “It is impossible to consider the drama profitably apart from the theatre in which it was born and in which it reveals itself in its completest perfection.”5 The scale models of historical theatres built to illustrate performance spaces by Matthews and his students may still be seen at Columbia. In a very fundamental way, the new orientation introduced by Herrmann and Mathews still serves as the most widely accepted model for historical research in theatre, as may be seen in a very recent articulation of the aims of the discipline by one of its leading scholars, Robert D. Hume. In a survey article on the “Aims, Materials, and Methodology” of theatre history in his period of specialization, 1660–1800, Hume observes, “I would suggest that one crucial function of the theatre historian is To demonstrate how production and performance circumstances affected the writing and public impact of plays.”6 One could hardly ask for a clearer or more concise statement of the Herrmann/Mathews project.

It is also important to understand in what ways the new orientation proposed by Matthews and Herrmann was revolutionary and in what ways it was not. Although the establishment of theatre history as a discipline offered a new methodology and new sources of investigation, its object for most of the twentieth century remained essentially the same as that of the tradition of dramatic literature in which it was grounded. That object was to provide a fuller and deeper understanding of the largely European works of the traditional canon. As the field developed in Europe and America, it focused its attention not upon the history of theatre in general, but upon the original performance conditions of those plays already established as the focus of literary study. It thus maintained a consistent, if unacknowledged, position as an adjunct to literature. Were one to attempt a definition of theatre history as it was practiced for much of the twentieth century, one might say it was “the study of the evolution, primarily in Europe and America, of the process of enacting literary dramatic texts.” The basic purpose for studying theatre history remained as Matthews and Herrmann saw it, that is, to provide important insights into the understanding of canonical literary figures like Shakespeare, Schiller, and Molière.

Were one to attempt to create a definition of theatre scholarship as it is practiced today, it might be something like “the study of particular theatrical and performative events, or groups of such events, and how they operate within their cultural contexts.” This more flexible definition avoids the now much discredited emphasis upon an evolutionary narrative, the still powerful if increasingly challenged emphasis on the European tradition, and the replacement of the literary emphasis, dominant in European theatrical theory ever since Aristotle, with a more general concern with theatre and performance as cultural activities.

The new orientation also has profound implications concerning how space is conceived and studied in relation to the theatre. Even when Matthews, Herrmann, and their followers insisted upon attention to the physical conditions of performance, their considerations of space were almost entirely confined within a fairly specific domain. At the heart of their idea of theatre was a basic spatial arrangement, the confrontation of the actor, occupying his or her own space, with the spectator, also occupying a particular space, and these two connected by a third, encompassing space, the theatre. One of the most fundamental characteristics of theatre is the separation of the real world of the spectator from the mimetic world of the actor, and although there are instances of the interpenetration of these worlds throughout theatre history, this invariably involves some sense of transgression, even danger. Even when spectators and performers have shared the same literal space, their psychic spaces remain different. The performer, as Herbert Blau and many modern theorists have noted, necessarily remains in the position and in the space of the Other.7

Thus it is hardly surprising that considerations of space by most traditional theatre historians have focused primarily upon the characteristics and elaborations of these three basic and interlocking spaces. Nor, given the literary orientation of such work, is it surprising that the space that has received the most detailed attention is the stage space, the space that is most directly involved in the presentation of the literary text. Any student of theatre is expected to be acquainted with such matters as the stage wall of the Roman theatre; the historical use of wings, drops, and shutters; and the development of a three-dimensional concept of stage space by the Romantics and, later, by Appia. Even in this most fully developed area of spatial investigation, however, theatre and performance studies still suffer from a focus on the European tradition. Aside from the special cases of Noh and Sanskrit drama, only in recent years have theatre historians begun to consider the spatial practice and its implications of non-European theatre.

Even what might seem the simplest and most universal use of performance space, an open circle created by a gathering of spectators around a performer or performers, provides a rich store of cultural insights as one examines its implications in different cultural contexts. To give only a single example, in late twentieth-century Arab theatre, when there was a strong interest in breaking away from European colonialist practice, many artists, from Morocco to Syria, rejected the proscenium theatre arrangement, widely considered the quintessential European theatre form, in favor

Figure 1.1 Audience in a circle called halqa in Arabic theatre. Courtesy of Khalid Amine.

of gathering an audience in a circle, a halqa, about the performers, creating a different sort of space with much more consciously porous boundaries between the audience space and the performance space. (Figure 1.1) Simply describing the space as such, however, does not in any way suggest its cultural complexity. In addition to the post-colonial dynamic of this spatial choice, a wide variety of other cultural concerns are involved, beginning with the relationship of the halqa space to the various cultural traditions of North Africa and the Middle East. This involves its use in folk festivals and in popular gatherings such as the Maghreb samir, and its association with the tradition of the traveling storyteller, the hakawati. Arabic theorists of the halqa have also noted its mystic and religious associations with certain religious symbols and ritual practice.8

A specific interest in analysis of the opposed space of the spectator has become a significant part of theatre studies only during the past half-century. A relatively early example was James J. Lynch's 1953 book, subtitled Stage and Society in Johnson's London. Its main title significantly looked to the spatial arrangement of audiences as the basic representation of this social orientation: Box, Fit, and Gallery. The rise of a specific sociology of theatre, pioneered by Georges Gurvich and Jean Duvignaud in France in the 1950s and 1960s, encouraged much more of this sort of historical analysis. Thus, for example, Timothy Murray, in his 1977 “Richelieu's Theatre: The Mirror of a Prince,” suggested how the spatial arrangements of this key historical structure expressed and reinforced a whole system of social power relationships.9 More recently, Joseph Donohue's 2005 Fantasies of Empire uses the controversies surrounding the arrangement of audience space in this theatre to illuminate a broad spectrum of social, political, moral, and legal questions in Victorian England.10

Without questioning the importance of theatre audience spaces as reflectors of social status, however, current scholarship has moved beyond the long-standing binary spatial study of the performance space on one hand and the audience space on the other. Theatre and performance scholars today are also considering a wide variety of other previously neglected spaces, the investigation of which promises to considerably increase our understanding of theatre and performance, particularly in the ways that they operate as social and cultural phenomena.

Even within the theatre building itself, current spatial analysis encourages us to look for how space is utilized beyond the long-privileged audience– performance confrontation. Backstage spaces, for example, important as they are to the functioning of what the public sees, rarely have been studied or even mentioned in our historical studies, and yet they also not only reflect social status but provide all manner of additional information about the actual physical creation and operation of the performance. Gay McAuley's 1999 Space in Performance, offered, to the best of my knowledge, the first attempt, aside from technical architectural studies, to consider in any detail such neglected spaces, both in the front and in the back of the theatre house. The former she designates as audience space and the latter as practitioner space, neither so fully documented or studied as stage space or auditorium space. Indeed she also includes a consideration of an even less known or documented space, rehearsal space, which, though never seen by the public, can have a significant impact on the final production.11

All of the spaces I have mentioned so far—that of the performer, the spectator, and, in the case of a theatre building, the space that unites and includes these other spaces—have formed the central spatial concerns of traditional theatre history. In recent years, however, as theatre scholars began to look at theatre less as a mechanism for the embodiment of dramatic texts and more as a cultural activity, this opened important other dimensions of spatial analysis. The foundations of the modern sociological study of theatre laid in France by Gurvich and Duvignaud were brought into English-language scholarship soon after by Elizabeth Burns in England and Richard Schechner in the United States. The importance of space in the theatrical experience was from the beginning a central concern for Schechner, and he was one of the first to note the importance not only of variations in relationships between the space of the actor and the space of the performer but also how other extra-theatrical spatial concerns (such as the space traversed in coming to and departing from the theatre) were potentially significant parts of performance analysis. An awareness of this first appears in Schechner's work in the mid-1970s, when he observes in his major essay “Toward a Poetics of Performance” that “too little study has been made of the liminal approaches and leavings of performance—how the audience gets to, and into, the performance place, and how they go from that place.”12

To take a single famous example, clearly the necessity of crossing the Thames by boat to reach the marginal, quasi-respectable entertainment district of Bankside, where the major Elizabethan public theatres were located, was a significant part of the mental contextualization of attending those theatres. Theatres utilize space in particular and meaningful ways internally, but Schechner and others pointed out that they also occupy space, and the amount and kind of space they occupy and the location of this space within the mental or experiential map of a community or a city obviously will affect the operations of, and audience attitude toward, that theatre.

Typically theatres are urban structures, and the kind of space they occupy and the associations of their neighborhood and the surrounding structures are extremely important indicators of the social and cultural positioning of the theatre in its community. Traditional theatre histories were highly selective about this sort of spatial concern. As usual, more attention was given to Shakespearian theatre than to the theatre of any other period or any other culture. Most theatre students are therefore at least generally aware of the significance of the English liberties and how important the geographical space occupied by the early public theatres in England is to an understanding of the history of those theatres. And yet traditional histories provide almost no information about the comparable geographical positioning of the early public theatre in France or Spain, to mention only two prominent examples. The same lack of information existed, and in many cases still exists, among most theatre historians about many of the most significant European theatres.

As an example, let us return once more to the notorious premiere of Ubu. Every standard theatre history provides details of this famous production, and of the place of its sponsoring organization, the Théâtre de l'Oeuvre, in the evolving French avant-garde, but rarely can one find the actual location of this theatre in Paris, and nowhere, even in the most specialized studies, is there any consideration of the social and cultural implications of this location. In the received history of the modern theatre, Parisian avant-garde theatre takes place in a location closely akin to Ubu's Poland, that is to say, nowhere. Yet for those who actually attended that performance, the physical location was unquestionably an important part of the experience. By the 1890s Paris had developed at least two distinct types of theatre: the state-supported “national” theatres like the Opéra and the Comédie, and the “boulevard” theatres, commercial houses whose name was derived from their original concentration on the old Boulevard du Temple, from which they were displaced by Baron Haussmann's massive urban renewal in 1861. Haussmann's new boulevards, however, provided for many of them a new home, and so most of the commercial, or boulevard, theatres of Paris are still located along the grandes boulevards Haussmann designed. We might note that the major commercial theatres of London and New York are also best known by their geographical locations: the West End and Broadway, respectively.

Just as the boulevard theatres had in 1896, and still have today, their acknowledged place on the mental and physical map of Paris, so did the national theatres, even more centrally located in the political and financial heart of the city, the first arrondissement. When the new experimental theatres at the end of the century began to appear, they sprang up in rather disreputable areas first to the north, then to the south of the city center, far outside the areas familiar to even adventurous theatre goers. The intrepid patrons of the first and most famous of the new avant-garde theatres, Antoine's Théâtre-Libre, truly had to venture into an urban terra incognito, a theatrical no-where. Jules Lemaître, one of the leading theatre critics in Paris in the 1880s, began his review of Antoine's first production with an evocation of its physical location which is worth quoting in detail to see how important location was in framing the event in his experience:

The address on the letter of invitation was 37, Passage de l'Elysée-des-Beaux-Arts, Place Pigalle. Thus, last Tuesday about 8:30 in the evening you may have seen dark shapes threading their way among the booths at the Montmartre fair, and winding hesitantly among the puddles of water on the pavement around the Place Pigalle, peering at the signs on the street-corner through their glasses—no such street, no such theatre.

At last we passed the light of a wine merchant and went on up a steep tortuous, dimly lighted street. A line of coaches slowly mounted, and we followed them. On either side were tumbledown hovels and dirty walls, at the far end a dim staircase. We looked like the three kings, in overcoats, in search of a hidden and glorious manger.13

After his opening production, Antoine moved to a nearby location on the rue Blanche, just off the Place Pigalle, already having a well-established reputation as a center of risqué entertainment in Paris. Shortly after, he moved again, in search of better facilities, to the even more remote Montparnasse area, on the other side of the Seine.

A decade later, when the Parisian magi in search of a new theatrical revelation made their pilgrimage to the Théâtre de l'Oeuvre to attend the premiere of Ubu roi, the mental map of the Parisian theatre had not fundamentally altered, but the emerging avant-garde had distinctly changed it, especially of course, in the minds of spectators like Lemaître, who sought to be alert to significant new trends in the arts. One still had to leave the fashionable entertainment districts of Paris and penetrate the more questionable and bohemian Montmartre area to attend Lugné-Poe's Théâtre de l'Oeuvre, but for such spectators that district now had imposed on the raffish associations of the Place Pigalle the memory of Antoine's pioneering avant-garde work, whose early days had been pursued just up the rue Blanche, on the same street where the Théâtre de l'Oeuvre was now located. The tumbledown hovels and dirty walls were still there, but they had now gained, at least for these spectators, the associations of the humble manger where dramatic art was experiencing its birth pains, yet still retained its power. One could clearly argue that something of this difficult pilgrimage remains for those spectators who brave the still marginal areas where Lugné-Poe presented Ubu to attend Peter Brook's Bouffes du Nord, or who seek out the still operating Living Theatre in the depths of New York's notorious Lower East Side, or who attend London's Arcola in the middle of a remote and distinctly marginal neighborhood of Turkish immigrants.

During the past decade recognition of the influence of such extra-theatrical space upon reception has become more and more evident in theatre studies. Susan Bennett, in her 1997 reception study Theatre Audiences, remarks “The milieu which surrounds a theatre is always ideologically encoded” and thus “shapes a spectator's experience,” and Bennett uses this insight to analyze the geography of Joan Littlewood's Theatre Workshop and a variety of other nineteenth- and twentieth-century theatres.14 Ric Knowles's 2004 study Reading the Material Theatre suggests this new orientation even in its title. In his introduction he explains: “This book attempts to develop a mode of performance analysis that takes into account the immediate conditions, both cultural and theatrical, in and through which theatrical performances are produced, on the one hand, and received, on the other.”15 In examples drawn from large and small theatres in a number of countries, Knowles demonstrates how the analysis of space both within and outside the theatre provides significant insights into these cultural and social processes.

My remarks so far have focused upon the second part of the Berlin conference title, “theatre and topology,” but I would like to conclude by looking, much more briefly, at the first part, “politics of space,” which opens up quite different but equally challenging perspectives. One of the most important developments in modern theatre studies has been the rise of an interest in the phenomenon of performance. In the United States many former departments of theatre have renamed themselves departments of theatre and performance, and in some cases performance studies has been established as a separate academic field, seen by some as a supplement to, and by others as a contemporary rival to, traditional theatre studies.

The institution most closely associated in the United States with the development of performance studies is New York University, where, in the early 1970s, Richard Schechner called for a new approach to the study of theatre, one much more aware of contemporary research in the social sciences. Schechner called for a broader and deeper consideration of the phenomenon of performance as a cultural activity. This included a broad range of activity, casual social gatherings, sports, play, ritual, and public events of all sorts. Traditional theatre Schechner characterized as “a very small slice of the performance pie.”16

Among the social scientists most influential for Schechner was Erving Goffman, who at the same time was developing his highly influential work on social performance. This he sought to analyze in highly theatrical terms, speaking of social behavior as “role-playing” designed to produce a particular effect upon those who observed it, the social “audience.” Goffman is very much aware of the importance of space in social performance and focuses upon it in a number of his writings, most notably in the 1974 book, Frame Analysis, a work of particular importance to Schechner and other pioneers of modern performance studies. Although the concept of “framing” in social theory can refer to any sort of interpretive grid used to understand and respond to phenomena, both Schechner and Goffman emphasized how it operated spatially. Of course, the concept of framing itself comes from the arts, and Goffman devotes an entire chapter of his book to theatrical framing, the various devices employed by the theatre, most notably the proscenium arch, to “frame” the spatial world of the play and to allow it to be accepted as a “here” different from the “here” occupied by the audience, even though the two spaces are in fact necessarily physically contiguous.17 Bert States, one of the leading English-language theorists to apply phenomenological analysis to the theatre, calls the particular kind of space created by a framing device like the proscenium arch, “intentional space,” which separates itself from the space of its viewers while still encouraging them to observe and interpret what occurs within it.18

Spatial framing also may be analyzed in a wide variety of situations outside the theatre, as Goffman observes, and its use is particularly evident in social situations and events in which the performative element is strong, that is, situations where the person or persons creating the event are clearly seeking to create a particular impression on the audience to which they are presenting themselves. Goffman gives as one example the executive who helps to project his role by sitting behind a massive desk in an impressive, wood-paneled office.

In contemporary society we are probably most aware of this sort of social framing in political events, which are obviously performances which can come very close to theatre, complete with role-playing, scripts, costumes, make-up, and of course, an appropriate physical setting. Politicians today are highly aware of the importance of their physical surroundings, whether they are addressing their audiences directly or speaking through the media of film or television. They also like to appear in impressive offices, if they wish to emphasize their bureaucratic importance, or on the decks of battleships, or among crowds of schoolchildren or cheering supporters, as those surroundings better frame the manner in which they wish their audiences to interpret their appearance. As a single recent striking example of this dynamic, I would like to conclude with a manifestation of the modern politics of space in the original ici of this essay, the city of Berlin, a city which, for decades has been one of the most important sites in the world for demonstrating the close relationship between politics and physical space.

On July 24, 2008, U.S. presidential candidate Barack Obama presented perhaps the most famous speech of his campaign in central Berlin. The location was in front of the Victory Column, the Siegessäule, in the heart of the Berlin Tiergarten, but the spatial significance of that site, and its selection, was a matter of intense and still-continuing political and social negotiation. Obama's original idea was to give his speech in front of the Brandenburg Gate, obviously seeking to evoke memories of support the United States gave to the German people during the postwar years of division. Among the most famous presidential speeches of those years, both outstanding moments during the Cold War, were presented by American presidents in Berlin, John F. Kennedy's “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech of 1963, delivered in the West Berlin square that today bears his name in memory, and Ronald Reagan's “Tear down this wall” speech in 1987. By speaking before this famous monument, now again a gate and not part of the wall, Obama could both spatially identify himself with his two most popular presidential predecessors in the memory of American voters, and also stand as a visual reminder of the fulfillment of their vision of a free and united Berlin and Germany.

Klaus Wowereit, the mayor of Berlin, welcomed the idea, but Chancellor Angela Merkel vetoed the plan, saying that the intrusion of a foreign electoral process was an inappropriate use of this space. The speech planners then turned to the Siegessäule (Victory Column) location, with a good view of the Brandenburg Gate about a kilometer away at the end of a boulevard. (Figure 1.2) The site was appropriately monumental and open for the large anticipated crowds, but no significant city space, especially a city with so layered and troubled a history as Berlin, is devoid of historical associations, and the planners of the event, although the Siegessäule remained their final

Figure 1.2 Obama's speech in Berlin, © ddpimages.com.

choice, had to suffer widespread criticism. Opponents pointed out that the monument was first erected in front of the Reichstag to commemorate Prussian victories over its neighbors and was moved to its present location in 1939 by Hitler as a central monument of his new Nazi capital.

As a result, there was a distinct disjuncture between the speech Obama gave, successful and well received as it was, and the space in which it was given. Central to the speech was a call for the tearing down of walls that today separate members of different backgrounds, and especially different religious faiths. Presented in the heart of Berlin, with the Brandenburg Gate in sight, the speech inevitably evoked, as Obama clearly desired, images of the Berlin Wall, America's strong support for the isolated city, and the memorable Kennedy and Reagan addresses.

It also provided an important illustration of the more general point I am making, about the close relationship between space and public political performance. A number of American commentators, for example, noted how much more daring and politically dangerous the exact same speech would have been had it been delivered in today's most famously divided city, Jerusalem, where the U.S. position on a political wall is considerably more troubled, and where the location would have cast the entire speech in a totally different and much more controversial light.

Today, as a the right-wing opposition to Obama grows increasingly vicious in their attacks on the president and his programs, the Berlin speech continues as a minor but troubling contribution to the campaign to cast him as a would-be totalitarian. The practice is now widespread in certain areas of the United States of drawing or pasting small Hitler-style mustaches on images of the president. The organizers of these campaigns of defamation have not forgotten the tumultuous welcome Obama received in Berlin, which they view not as evidence of his international popularity, but of his ability as a charismatic leader, to stimulate mass adulation in the same way that Hitler did. Seen from this perspective, the selection of a gathering site here in Berlin so significant to the dynamics of the Hitler regime and its rallies, calls forth associations far from those desired by Obama's managers of public relations.

In this single striking example from modern international politics we can see how the politics of space reverberate resoundingly through our performative culture. The “here” where an event occurs may so profoundly affect the event that it overshadows the “what” of the event itself. Theatre, that central performative art, has always been grounded in topology, but only recently have we become aware of how important topology is to the entire social fabric which theatre reflects.

1. http://www.ici-berlin.org/institute/about-the-institute (accessed October 1, 2011).

2. Thornton Wilder, “Some Thoughts on Playwriting,” in August Centeno (ed.), The Intent of the Artist (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1941), 81–98, 89.

3. John Keats, The Poems of John Keats, ed. Jack Stillinger (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, 1978), 503.

4. Alfred Jarry, Tout Ubu (Paris: Librairie Générale Française, 1962), 21.

5. Brander Matthews, A Study of the Drama (New York, 1910), 3.

6. Robert D. Hume, “Theatre History 1660–1800: Aims, Material, Methodology,” in Michael Cordner and Peter Holland (eds.), Players, Playwrights, Playhouses: Investigating Performance, 1660–1800 (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave, 1007), 11. Italics in original.

7. Herbert Blau, “Universals of Performance; or, Amortizing Play,” Sub-Stance 37–38 (1983), 148.

8. See Khalid Amine and Marvin Carlson, “Al-halqa in Arabic Theatre: An Emerging Site of Hybridity,” Theatre Journal 60:1 (March 2008).

9. Renaissance Drama NS 8 (1977), 275–297.

10. Fantasies of Empire: The Empire Theatre of Varieties and the Licensing Controversy of 1894 (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2005).

11. Gay McAuley, Space in Performance: Making Meaning in the Theatre (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999), 70–80.

12. Richard Schechner, Essays on Performance Theory 1970–1976 (New York: Drama Book Specialists, 1977), 122.

13. Quoted in André Antoine, Memories of The Théâtre-Libre, trans. Marvin Carlson (Coral Gables: University of Miami Press, 1964), 47.

14. Susan Bennett, Theatre Audiences (London: Routledge, 1997), 126–130.

15. Ric Knowles, Reading the Material Theatre (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 3.

16. Richard Schechner, “A New Paradigm for Theatre in the Academy,” The Drama Review 36:4 (1992), 10.

17. Erving Goffman, Frame Analysis (New York: Harper and Row, 1974).

18. Bert O. States, Great Reckonings in Little Rooms (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), 50.

Amine, Khalid and Carlson, Marvin, “Al-halqa in Arabic Theatre: An Emerging Site of Hybridity,” Theatre Journal 60:1, March 2008.

Antoine, André, Memories of The Théâtre-Libre, trans. Marvin Carlson, Coral Gables: University of Miami Press, 1964.

Bennett, Susan, Theatre Audiences, London: Routledge, 1997.

Blau, Herbert, “Universals of Performance; or, Amortizing Play,” Sub-Stance 37–38, 1983, 140–161.

Donohue, Joseph, Fantasies of Empire: The Empire Theatre of Varieties and the Licensing Controversy of 1894, Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2005.

Goffman, Erving, Frame Analysis, New York: Harper and Row, 1974.

Hume, Robert D., “Theatre History 1660–1800: Aims, Material, Methodology,” in Michael Cordner and Peter Holland (eds.), Players, Playwrights, Playhouses: Investigating Performance, 1660–1800, Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave, 2007, 9–44.

Jarry, Alfred, Tout Ubu, Paris: Librairie Générale Française, 1962.

Keats, John, The Poems of John Keats, ed. Jack Stillinger, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, 1978.

Knowles, Ric, Reading the Material Theatre, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Lynch, James J., Box, Fit, and Gallery: Stage and Society in Johnson's London, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1953.

Matthews, Brander, A Study of the Drama, New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1910.

McAuley, Gay, Space in Performance: Making Meaning in the Theatre, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999.

Murray, Timothy, “Richelieu's Theatre: The Mirror of a Prince,” Renaissance Drama NS 8, 1977, 275–297.

Schechner, Richard, Essays on Performance Theory 1970-1976, New York: Drama Book Specialists, 1977.

Schechner, Richard, “A New Paradigm for Theatre in the Academy,” The Drama Review 36:4, 1992, 7–10.

States, Bert O., Great Reckonings in Little Rooms, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.

Wilder, Thornton, “Some Thoughts on Playwriting,” in August Centeno (ed.), The Intent of the Artist, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1941, 81–98.