Figure 6.1 Beheaded prophets. Idomeneo directed by Hans Neuenfels. Photo credit: © Mara Eggert.

Censorship, Artistic Freedom, and the Theatrical Public Sphere

Christopher Balme

What are the limits of tolerance in situations of cultural and religious pluralism? And how do we, how do states police these limits, prevent them from being so severely tested that concerned groups feel provoked to protest against the constitutionally protected rights of other groups to practice their cultures, voice their opinions, or even, most provocative of all, lay claim to artistic freedom and thereby, potentially, and actually, overstep the line demarcated by tradition rather than law, which I would like to term the “thresholds of tolerance”? Such infringements on the thresholds of tolerance are generally policed by censorship. I define censorship here as any kind of institutionalized form of control over the freedom of expression exercised by state, or semi-state bodies. This may be in the form of the office of censor, the Lord Chamberlain for example, or by indirect means—ultimately the ideal form—of internalized rules and proscriptions, where those active in the public sphere (journalists, writers, artists, preachers, etc.) abide by the rules. East Germany, for example, had no official censor but it certainly had censorship. West Germany then and Germany today also had and has censorship, as we shall see, even though freedom of opinion is enshrined in the German constitution. In fact all polities practice censorship of one form or another in order to ensure the maintenance of cultural and religious values and to protect these values against infringement. The establishment and maintenance of such censorship bodies mark thresholds of tolerance.

In Western liberal democracies, such thresholds tend to run along age lines and not those of political or artistic opinion. Access to certain cultural products is often restricted to persons under a certain age. But they are also indissolubly linked to physical spatial realms. As we shall see, thresholds are both metaphorical and actual, conceptual and pragmatic. The question of where people may gather to articulate their opinions or to represent their stories determines whether or not censorship needs to be enforced.

In this chapter I explore some of the issues involving tolerance, censorship, and the limits imposed by them and on them in the context of theatre and performance. In the first section I discuss recent ideas on tolerance developed by Jürgen Habermas where he elaborates what he terms the “paradox of tolerance,” which consists in having to circumscribe and place limits on what can be included and excluded from tolerance itself. In the second section I examine some of the contradictions inherent in censorship in open societies such as Germany which emphasize the importance of free speech while at the same time practicing regimes of censorship in certain media. Finally I look at two examples of censorship and the arts where questions of religious affiliation determine when and how censorship in a country such as Germany is in fact practiced and enforced.

In a number of recent essays on religion and cultural pluralism, Jürgen Habermas has explored the changing status of concepts such as tolerance, which we tend to take for granted as a hallmark of liberal democratic societies, of which my elected country of residence, Germany, is an example. As Habermas points out, the term “tolerance” is, in its German version Toleranz, a relatively recent coinage, dating from the 16th century and the period of confessional strife, the Reformation.1 From there it slowly solidified into a juridical concept. Rulers and governments began to issue laws and edicts legislating “tolerance” and imposing its observance on citizens: The Edict of Nantes 1598 and the English Toleration Act of 1689 are examples of this necessity to impose an attitude which we would more normally associate with internalized subjective viewpoints. The juridical encoding and enforcement of tolerance were clearly seen as a requirement for the peaceful cohabitation of religious groups in situations of propinquity.

Although the almost resolved Troubles in Northern Ireland belie my assertion, I would still like to claim that liberal democracies on the Western model have broadly achieved their goal of shifting the idea of tolerance from the realm of juridical enforcement to the sphere of individual internalization. In secular liberal democracies predicated on the separation of church and state, tolerance is a state of mind, a self-evident state of affairs, and not a contested legal concept. Despite evident “progress” on such complex questions, Habermas draws our attention to remaining unresolved problems involving tolerance, especially in situations of poly-religious and poly-ethnic cohabitation that have become the norm throughout most postindustrial societies. He points to a paradox of tolerance whereby the very act or attitude of exhibiting tolerance can be construed as insulting, because it implies a condescending attitude toward those groups or people to whom one is “tolerant.” This apparent paradox can be resolved, Habermas argues, on the basis of reciprocal recognition of rules of tolerant dealings. The paradox of an intolerance that inheres in every attempt to draw boundaries of tolerance cannot be completely resolved by generalizing the freedom of religion as a basic right. Intolerance toward certain behaviors is an integral part of every democratic order because constitutions need to be protected against enemies. Even the liberal democratic state must behave intolerantly against enemies of the constitution such as fundamentalist and political extremists who reject the principles of such constitutions. Although religious tolerance would seem to be an essential pacemaker for a correctly understood form of multiculturalism, it still does not precisely define the limits or even the burden of mutual tolerance that Habermas terms Toleranzzumutungen (impositions or heavy expectations placed on a tolerance). Tolerance does not mean indifference toward the different convictions and practices or even a positive estimation of the Other and his or her Otherness because then, tolerance becomes meaningless. We can only speak of tolerance when the involved parties base their rejection of the other's beliefs in terms of a rationally understood, continuing state of non-agreement. Tolerance certainly requires the overcoming of prejudices and outright discrimination, but it does not involve the sacrifice of one's beliefs in favor of or indifference to other groups. It is in the demarcation and policing of such boundaries that tolerance in a democratic society must be defined and practiced. Even in a society such as Germany, the development of such ideas still needs to be further refined: Expectations of tolerance are still subject to differential expectations that run along religious lines. When the limits of tolerance are tested, the possibilities of censorship, despite its habitual disavowal within a liberal democracy, are quickly evoked.

Both Western liberal democracies I have lived in most of my life maintain a state body to censor films. In New Zealand this was termed in my childhood and youth quite explicitly the film censor whose job it was to apply age restrictions, excise offending scenes, even ban whole works deemed unsuitable for public exhibition. The most extreme case I can remember in the 1960s was the film version of James Joyce's Ulysses, a now largely forgotten film, where screenings were only permitted to adults over the age of 21 and in sexually segregated screenings. The United States had the infamous Hays Production Code and still has, like most countries, a similar system of age gradation.

In Germany, censorship of film and media products in general is divided between two bodies: The film industry itself issues so-called FSK certificates, Voluntary Self-Regulation of the Film Industry, a film classification system along age lines. Following Lenin's edict that trust is good, but control is better, more direct censorship is exerted by the Federal Department for the Examination of Media Harmful to Young Persons (Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährdende Medien). A controversial institution, its highly erratic decisions continue to annoy connoisseurs of genres such as horror and splatter films as it is often difficult to know just when and whether a film is on the index. Today its main field of battle is the arena of computer games.2

The ubiquity of film and media censorship in Western liberal democracies serves to demonstrate that all complex societies require, it would seem, censorship of media products. The innate human tendency to want to depict and watch scenes of a sexual, violent, or generally depraved and transgressive nature in all media, whether old or new, needs to be counteracted by controls to regulate this tendency as it affects toleration thresholds on a number of levels. These are usually of a religious or cultural nature and are almost always highly selective. One group's offensive material is another's idea of enjoyable evening entertainment. My interest here is to explore how in situations of cultural pluralism the thresholds of tolerance are policed in asymmetrical fashion. The application—or, conversely, the withholding—of censorship tells us much about value systems in open societies and particularly the differential degree to which cultural pluralism is in fact acknowledged.

In Germany the space of theatre provides a particularly accurate indicator of asymmetries because here there is no official censorship. As a highly subsidized art form, theatre, at least that purveyed by the public institutions, enjoys generalized protection by the constitution under article 5, paragraph 3 of the Basic Law. To understand more accurately the dynamics of German theatre's virtual freedom from censorship, a brief digression on the nature of audience and spectatorship is required. I have argued elsewhere that in theatre studies we tend to be somewhat unclear about categories such as spectators, audiences, and the public or public sphere. The rest of my argument is based, however, on clear distinctions between four realms of spectatorship:

• Spectator: an individualized aesthetic subject

• Audience: a collectivized aesthetic subject

• Public: a to-be-realized potential audience

• Public sphere: a possibility and space of communication3

To understand the absence of censorship in formal or informal forms, we have to accept that what goes on in the privacy of a German theatre has largely become an entirely private matter. It is an artistic act conducted between two consenting partners, the performers and the spectators, and is therefore seldom of interest to the wider public sphere, theatrical or otherwise. Even when presented with nudity, obscenities, or verbal abuse, a German subscription season audience has seen and heard a lot and is usually prepared to take some punishment. Doors will on occasion be slammed, as enraged and offended spectators leave the auditorium, and letters to the editor are written, but these are exceptions to a generally accepted state of tolerance: Just as boys will be boys, so too will artists be artists.

This general state of indifference can be challenged, however, and I wish to briefly discuss two such cases. In each case we have to be aware of the distinctions between the performance and the public sphere.

But what public sphere are we talking about? Any theoretical discussion of the term must begin with the seminal book by Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, first published in German in 1962 but not translated into English until 1989. Habermas divides the public sphere into two historical iterations: a representative form typical of feudal and absolutist political regimes, where most political action is ruled by the dictates of secrecy, arcana imperii, on the one hand, and carefully staged forms of publicness in the context of absolutistic rule on the other. The second form that comes to replace the representative one he terms “bourgeois.” Its main characteristics are almost universal access, autonomy (participants are free of coercion), and equality of status (social rank is subordinated to quality of argument). The bourgeois public sphere emerges within late feudal society, initially in the “nonpolitical” arenas of the theatre, literature, and the arts, where the discursive patterns and practices are trained, as it were, before entering the political arena proper. The defining feature of the bourgeois public sphere is reasoned discourse by private persons on questions of public interest with the aim of achieving rational consensus.

Since the term's original definition by Habermas, the semantic field of the term “public sphere” has been extended considerably, especially in the wake of the English translation of Habermas's book in 1989. The English translation of the German term Öffentlichkeit as “public sphere” is somewhat problematic because it does not adequately cover the semantic flexibility of the original. Öffentlichkeit connotes in the first instance, depending on the context, persons, not a space, albeit in a collectivized and abstract sense. In this rendering it is closer to the term “public” or, in a conceptual sense, “publicness.” Öffentlichkeit does not have a clear spatial orientation suggested by the word “sphere.”4 The spatiality of the term is not, however, just a chance residue of translation. In Habermas's definition of the concept and particularly in the context of its historical emergence, it can be thought of concretely in terms of a particular space. Central to the concept is the distinction between public and private spheres. As bourgeois society placed ever more emphasis and value on privacy and the private realm, particularly on the conjugal family in contrast to the theatrical openness of aristocratic intercourse, so too did it define and emphasize the importance of public discourse. This took place either through media, such as journals, newspapers, books, or, as Habermas famously argues, in new socially sanctioned spaces of communication, such as salons and coffee houses. Here meanings were made, opinions formed and debated, and the seeds of democratic processes sown. In a recent, autobiographical note, Habermas emphasizes two types of Öffentlichkeit. The first kind refers to the public exposure demanded by a media society linked to staging practices of celebrities with a concomitant erasure of the borders between private and public spheres. The second type, more narrowly the public sphere in the theoretical sense, refers to participation in political, scientific, or literary debates where communication and understanding about a topic replace self-fashioning. In this case, Habermas writes, “the audience does not constitute a space for spectators and listeners but a space for speakers and addresses who engage in debate.”5

Beyond its spatial connotations, the public sphere has become a concept sui generis. The public sphere does not just exist as a specific place of communication, it is also a conceptual entity with a history and discrete semantic dimensions. Since this identity has a diachronic dimension, it changes over time. It is also subject to social differentiation on the synchronic plane. An important part of Habermas's argument focuses on the multiple semantic dimensions of the term “public.” It must be seen not just in contradistinction to the idea of the “private” but also in the terms and sense of public service—that is, the emergence of bureaucratic institutions developed as a counterbalance to the “representative” publicness of feudal rule.6 While the diachronic dimension lies at the heart of Habermas's argument—the structural transformation and ultimately degeneration of the public sphere in its ideal-typical form—its social and functional differentiation is less apparent in the original formulation. A focus on differentiation, however, is one of the major contributions of recent studies of the idea of the public sphere. Today it is more usual to speak of public spheres in the plural rather than as one single entity. Recent research has identified the formation of public spheres along class, racial, and gender lines, to name only a few possibilities.7

For a theatre-historical perspective it is important to understand the public sphere as a relational object. Certainly the public, and perhaps also the public sphere in its spatial sense, come to be regarded as something that can be acted on, appealed to, influenced, and even manipulated. This conception of a somewhat passive entity provides ultimately the precondition for the emergence of the practices of publicity, public opinion, and public relations. All institutions highly dependent on public participation (for example, museums, concert houses, or theatres), expend considerable energy in assessing the nature of the public and the public sphere. What are their spatial and quantitative limits? How can the public be reached, exploited, or nurtured?

While it is normal to regard the theatre itself as a kind of public sphere, even this understanding is subject to historical processes whereby the relationship between the private and the public can be seen to shift. Up until the late nineteenth century, a theatre auditorium was regarded as a major public gathering space and therefore a space with the potential for political discussion and unrest. This potential has long been recognized by regimes of censorship, both past and present. Censorship implies a deep conviction regarding the political potential of the theatrical gathering. Where censorship reigns, the theatrical audience is potentially at least a part of the wider public sphere.

In the course of modernism, however, when theatre began to be increasingly redefined as an art form, the theatrical public sphere shifts from inside the theatre to outside—a process of eversion with far-reaching implications for theatre's institutional and cultural functions. The abolition of censorship in Germany in 1918 and in the United Kingdom in 1968 (to give just two examples) signaled in the former case a new constitutional right to freedom of expression, in the latter a long overdue recognition of theatre's increasing irrelevance as a player in the wider public sphere. That the theatre in Germany after 1918 was subject to an unprecedented number of scandals, riots, and forms of informal censorship, suggests that the abolition came too soon, or that its institutional function in a highly politicized and polarized society needed to be radically readjusted.8

In summary, the theatrical public sphere must be understood as the interaction of these three mutually dependent categories. The spatial concept of a realm of theatrical interaction primarily outside the building merges into a conceptual entity that becomes ultimately so palpable that it functions as an extension of the institution.

I wish to look now briefly at two theatrical controversies involving censorship, non-censorship, blasphemy, and interaction in the public sphere. We shall see how examples of provocative performances involving potential

Figure 6.1 Beheaded prophets. Idomeneo directed by Hans Neuenfels. Photo credit: © Mara Eggert.

offense to religious sensibilities are handled differentially in the public sphere and in legal rulings (the latter of course have a major impact on the public sphere, although they are strictly speaking not constitutive of it). The differences in reaction throw up important questions involving the thresholds of tolerance that Habermas defines as being crucial for coexistence in pluralistic societies.

The first example is the Idomeneo scandal that erupted in Berlin in 2006. The story begins in 2003 when Hans Neuenfels directed Mozart's Idomeneo at the Deutsche Oper in Berlin. In his production, he created an epilogue in which the title figure Idomeneo places the severed heads of the major prophets of world religion—Poseidon, Christ, Buddha, and Mohammed—on chairs.

The critical reaction after the premiere questioned the dramaturgical function of the new scene but made no reference to its blasphemous potential. The production then disappeared and was rescheduled for another run in September 2006 as part of Mozart-year celebrations. On September 26, the artistic director of the Deutsche Oper, Kirsten Harms, called a press conference and announced that she had cancelled the performances.

The next day the New York Times carried the following report on the front page:

A leading German opera house has canceled performances of a Mozart opera because of security fears stirred by a scene that depicts the severed head of the Prophet Muhammad, prompting a storm of protest here about what many see as the surrender of artistic freedom. The Deutsche Oper Berlin said Tuesday that it had pulled “Idomeneo” from its fall schedule after the police warned of an “incalculable risk” to the performers and the audience. The company's director, Kirsten Harms, said she regretted the decision but felt she had no choice. She said she was told in August that the police had received an anonymous threat, but she acted only after extensive deliberations.9

The reaction to the decision was astounding in that it made world headlines although there was never any confirmation of the threat from an individual or group. It remained hearsay and rumor with considerable repercussions. Intense debate ensued in the German media with the offending scene being shown repeatedly on television news programs. Two weeks into the scandal a kind of consensus was reached in Germany, at least on the part of the media and the many politicians who raised their voices: Artistic freedom must be given preference over any kind of security questions or religious sensitivities. It is imperative that one not capitulate before Islamic fanaticism: The show must go on. Harms was effectively pressured to reschedule the production and, when it went on again in December 2006, the first performance took place under heavy security, intense media scrutiny, and without incident.

Figure 6.2 Security measures at the Deutsche Oper in Berlin, December 2006. Photo credit: © www.ddpimaeges.com.

While there is no doubt that artistic freedom enjoys an extremely high degree of constitutional protection in Germany, a principle evidently of such standing that political involvement at the highest level could be mobilized for its enforcement to ensure that the show went on, another scandal from Bavaria's liberal capital, Munich, needs to be factored into the equation.

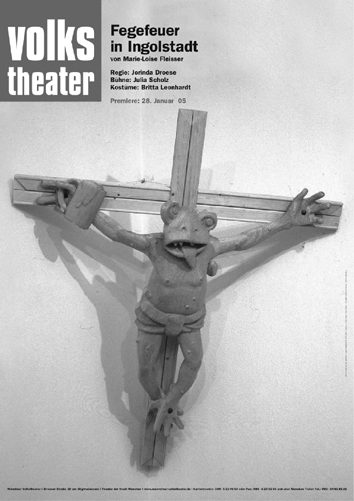

In December 2004 numerous German newspapers published a report, disseminated by the Austria Press Agency.10 Under the headline “Catholics Incensed: Take the Frog off the Cross,” the article described how Munich's second municipal theatre, the Volkstheater, had been forced to withdraw a poster criticized for blasphemy. It depicted a crucified frog with its tongue hanging out and holding a full beer stein in one hand. “In no way did we want to offend the religious feelings of people with our choice of image,” the artistic director Christian Stückl was quoted. With its poster, which is also reprinted on other publicity material, the municipal theatre wanted to publicize its production of Purgatory in Ingolstadt by Marie-Luise Fleisser, due to premiere on January 25, 2005. Munich's mayor Christian Ude (SPD), who had convened a special meeting of the Council of Elders to discuss the controversy, welcomed the decision. He considered that the poster offended religious feelings despite its artistic nature. The image is based on a work by the artist Martin Kippenberger who died in 1997. His wood sculpture had already been displayed in the exhibition Grotesk at Munich's Haus der Kunst. Stückl, well known for his staging of Everyman at the Salzburg festival and as the director of the world famous Passion Play in his home town of Oberammergau, stressed that it had never been the intention of the Volkstheater to create publicity by means of provocation, shock, or blasphemy, and none of the previous posters had done this. Stückl remarked: “The central focus was and continues to be an artistic and thematic debate.” He stressed that the printing of the poster had been stopped and, as far as possible, the other publicity material would be withdrawn.

It was above all Munich's Catholic citizens who had been incensed by the poster. “The image vilifies Christianity's central symbol,” criticized the general vicar of the archbishopric Munich-Freising Robert Simon. The head of the Christian Social Union in the city council, Hans Podiuk, declared: “It's been a long time since I have experienced such a drastic case of blasphemy.” The posters have to be destroyed immediately, demanded Podiuk. Simon also insisted that the posters be withdrawn. Podiuk said it was monstrous that a theatre subsidized by the city should “foster this vilification of Christianity.” Simon, too, declared that “the city of Munich which spends 4,6 million Euro annually in tax payers' money on the theatre, can simply not tolerate such an attack on a large section of citizens.” Simon and Podiuk both posed the question whether possibly the criminal charges could be brought under the law against offense to religious groups.

In the Munich frog case we find almost the identical arguments and situations we encountered in the Idomeneo scandal:

• A theatre-related image offends religious feelings.

• There is high-level political involvement and consensus across party lines: A social democratic mayor and conservative Catholic (CSU) party boss, normally at loggerheads, join forces in an unusual show of unity.

• The artistic director bows to political pressure.

• Even the link between public subsidy and artistic freedom has a parallel in the Idomeneo case, where a prominent American intellectual, the director of the American Academy in Berlin, blamed the situation on the high level of public subsidy enjoyed by German opera houses.11

In the case of the Munich poster, although based on the work of a very famous contemporary artist and which had already been exhibited in Munich without protest, the picture now loses its constitutional protection. Not only that, but criminal charges under the law prohibiting offense to religious groups are mooted, an idea never articulated by any leading political or church figures in the case of Idomeneo to my knowledge, although the image is equally if not more inflammable—if only to Muslims. From these differences we can conclude that the constitutional safeguards of artistic freedom and thereby freedom from censorship are culturally relative and dependent primarily on shifting configurations of discursive power that demonstrate in turn the efficacy of censorship in an open society.

To return to the problem posed at the beginning: How can we see censorship as a productive measure with which to protect the thresholds of tolerance? The cases highlight a conflict between two rights: the constitutionally safeguarded freedom of artistic expression on the one hand and protection

Figure 6.3 Poster of Purgatory in Ingolstadt. Photo credit: by permission of the Munich Volkstheater.

against religious abuse on the other set down in the criminal code. Both cases would seem to demand some form of censorship in the sense defined here of defining and protecting thresholds of tolerance. Freedom of art may be anchored in the German constitution, but the German criminal law code also contains a ban on blasphemy. For good reason it is illegal to intentionally offend religious sensibilities (§ 166 StGB) or to defame ethnic groups (§ 130 StGB) in such a way that the public peace is endangered.

The limits of constitutional freedom of artistic expression and the discursive power held by church authorities in Germany (especially the Catholic Church) had been tested in the mid-1990s in a blasphemy case involving a planned theatrical production critical of and lampooning fundamental tenets of the Catholic faith. In 1994, in the small and very Catholic city of Trier, a so-called rock-comical, inspired by the spirit, if not the music of Frank Zappa, titled The Mary-Syndrome, was banned before the premiere.12 The mayor of the city, himself a Catholic and member of the group Opus dei, effected a prohibition by invoking the blasphemy paragraph in the criminal code. Although the writer and composer of the musical contested the initial decision and went through all avenues of legal appeal up until the Federal Administrative Court of Appeal (Bundesverwaltungsgericht), the initial decision was always upheld. Because the content of the musical was deemed to be blasphemous, it was seen to fulfill the conditions of the law whereby offense to a religious group has the potential to disturb the peace.

In all three cases, I would argue, were the thresholds of tolerance transgressed, but when the dominant Christian majority feels threatened, it can quickly and efficiently eliminate any debate on artistic freedom and thereby effectively exercise censorship. The discursive configuration enabling the application of censorship hinges on the distinction between the private and public sphere: That is, it depends where the images are exhibited. In the private, intimate sphere of theatrical performance constitutional safeguards would seem to pertain: Idomeneo on stage, and in particular the offending image, enjoy protection; the crucified frog in a major museum is less of a problem than a publicly exhibited poster. In the case of the Mary-Syndrome, it was above all a poster depicting a pregnant nun that initiated opposition and ultimately court proceedings. It would be interesting to speculate, whether opposition to the performance would have been so fierce if it had stayed within the confines of the small performance space in which it had been planned.13

Although artistic freedom is unconditionally guaranteed in the German constitution (Basic Law), its limits are demarcated not just in the basic rights of third parties. These limits can also collide with other constitutional guarantees, for an ordered social life assumes not only mutual respect on the part of citizens but also a functioning state order, which is the prerequisite that constitutional rights are safeguarded in the first place. Works of art that might disturb this constitutionally safeguarded order are therefore subject to restrictions not just when they endanger the existence of the state or the constitution. Rather, in all cases in which other constitutionally protected interests come into conflict with the freedom of art, a reasonable balance between these different constitutionally protected interests must be found with the goal of achieving some kind of optimal balance. This was the argument made by the Federal Court, which upheld the ban of the performance of the Mary-Syndrome.

Of crucial importance in all these cases is the spatial factor. In theatre, and probably art in general, it is not enough to debate such questions on the level of ideas and principles, as Habermas does. Thresholds of tolerance are negotiable and reconstitute themselves along spatial and not just conceptual lines. In all cases the political intervention happened once the theatrical images in question left the privacy of the theatrical and entered the public sphere. It is at this level that some form of censorship appears to be required if peaceful cohabitation of different religious groups is to be sustained. The extreme differences in reaction in the examples discussed— freedom of art before blasphemy in the case of Idomeneo at the expense of Germany's Muslim minority, and the exact opposite reaction to Kippenberger's Frog on a Cross—indicate that in Germany's multicultural society, much work still needs to be done in terms of demarcating and policing the thresholds of tolerance in the public sphere.

1. Jürgen Habermas, “Religiöse Toleranz als Schrittmacher kultureller Rechte,” in Zwischen Naturalismus und Religion: Philosophische Aufsätze (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2005), 258–278.

2. An example of this erratic “indexing” process is the splatter film Braindead by New Zealand director Peter Jackson. On its release in Germany in 1992, it enjoyed a normal showing in mainstream cinemas; today it is illegal to purchase or exhibit the film in Germany.

3. For a more detailed discussion of this differentiation, see Christopher Balme, Cambridge Introduction to Theatre Studies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 35ff.

4. In the German original, Habermas refers continually to Öffentlichkeit as a Sphäre so that the English rendering of the term as “public sphere,” while emphasizing spatiality more than the German, is very close to Habermas's elaboration in some respects.

5. Habermas, Zwischen Naturalismus und Religion, 15, my translation.

6. Habermas's historical argument hinges on two transformations: from a feudal “representative” public sphere to a bourgeois rational-critical one during the eighteenth century, and then to the degeneration of the latter in the late-nineteenth and twentieth centuries under the influence of mass media and the commodification of culture.

7. The reception of Habermas's book in the English-speaking world only really begins in the 1990s in the wake of its translation in 1989. The first critical stock-taking can be found in Craig Calhoun (ed.), Habermas and the Public Sphere (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992); see especially his “Introduction.” A review of post-1992 research and criticism of the concept within historical studies is provided by Andreas Gestrich, “The Public Sphere and the Habermas Debate,” German History 24:3 (2006), 413–430.

8. For a discussion of censorship and scandals in the Weimar Republic, see the study by Neil Blackadder, Performing Opposition: Modern Theater and the Scandalized Audience (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2003).

9. Judy Dempsey and Mark Landler, “Opera Canceled over a Depiction of Muhammad,” New York Times (September 27, 2006).

10. Friday, December 17, 2004. All quotations are from the press release are my own. The original German news report can be found at http://www.n-tv. de/306186.html (accessed October 13, 2010).

11. The New York Times quoted Gary Smith, who, in a bizarre twist of logic argued that the levels of subsidy received by Germany's theatres were an indirect cause of the problem: “Because they are subsidized by the German state, there is a great deal of artistic independence, but also a lack of accountability and intellectual rigor”; see Dempsey and Landler, “Opera Cancelled.”

12. For an English summary of the case, see www.maria-syndrom.de/kampl.htm (accessed October 13, 2010).

13. See also the decision on the so-called pig on the cross case, in which the picture of a pig nailed to a cross and printed on a T-shirt was being marketed over the Internet. This was not considered blasphemous enough to fulfill the criteria of disturbing the public peace. See http://www.jurpc.de/rechtspr/19980109.htm (accessed October 13, 2010).

Balme, Christopher, Cambridge Introduction to Theatre Studies, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Blackadder, Neil, Performing Opposition: Modern Theater and the Scandalized Audience, Westport, CT: Praeger, 2003.

Calhoun, Craig (ed.), Habermas and the Public Sphere, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992.

Dempsey, Judy and Landler, Mark, “Opera Canceled over a Depiction of Muhammad,” New York Times, September 27, 2006.

Gestrich, Andreas, “The Public Sphere and the Habermas Debate,” German History 24:3, 2006, 413–430.

Habermas, Jürgen, Zwischen Naturalismus und Religion: Philosophische Aufsätze, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2005.

http://www.jurpc.de/rechtspr/19980109.htm (accessed October 13, 2010).

http://www.maria-syndrom.de/kamp1.htm (accessed October 13, 2010).

http://www.n-tv.de/306186.html (accessed October 13, 2010).