10 Heterotopias of the Public Sphere

Theatre and Festival around 1800

Patrick Primavesi

Translation by Michael Breslin

and Saskya Iris Jain

Michel Foucault's concept of heterotopia is quite helpful in the description and analysis of the development of European theatre around 1800. The transition from courtly to bourgeois culture in particular was accompanied by a multitude of heterotopias that determined the development of theatre for a long time and that still or again play a role in contemporary forms of theatre. This in particular concerns the idea of the public sphere and the closely related vision of a festive transgression of the stage toward an all-encompassing community of the audience, the nation, or even toward the fraternization of all human beings, as invoked by Friedrich Schiller. But these new aspirations also revealed the tension between heterotopian and utopian elements in the theatrical discourse throughout the German-speaking world around 1800. To investigate this tension in more detail, the following remarks will outline how Foucault's concept of heterotopia can be applied to the practice of theatre that has repeatedly sought to evade the principally utopian ideal of a discursive public sphere. Starting with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's novel Wilhelm Meister, I demonstrate how the ambivalent stance adopted by bourgeois culture toward theatre, festival, and public sphere unfolded in heterotopias, reflecting the spread of theatre across society. Focusing on the (self-)reflection of theatre in that period, I conclude by developing certain aspects fundamental to all the heterotopian ideas of the public, that remain relevant to contemporary questions concerning the places and localization of theatre in society.

FOUCAULT'S CONCEPT OF HETEROTOPIA, THE THEATRE, AND THE IDEA OF THE PUBLIC SPHERE

In his essay “Different Spaces,” adapted from a 1967 lecture to architects in Paris, Foucault outlines a “history of space.” What he describes is the transition from the religious principle of localization to a rational, purposeful concept of extension through space, then, finally, to a modern economy of storage or emplacement.1 Notwithstanding the accompanying desacralization of space since Galileo, Foucault's thoughts on contemporary conceptions of space proceed from what he believes are remnants of the sacred, which continue to dominate the customary divisions between private and public, family and society, culture (or leisure) and work. The reflection on space in terms of utopias and heterotopias, too, is based on these binary oppositions. Unlike the utopias of an ideal and perfect world, which is delegated, one might say, to illusory spaces, heterotopias are real places that question the rules governing hierarchical emplacements. Whereas utopias have a stabilizing effect, heterotopias are always a potential disruption to symbolic orders. This is something that Foucault also observes in his work The Order of Things from 1966, which investigates the changes to language and its systematic functions since the seventeenth century:

Utopias afford consolation: although they have no real locality there is nevertheless a fantastic, untroubled region in which they are able to unfold; they open up cities with vast avenues, superbly planted gardens, countries where life is easy, even though the road to them is chimerical. Heterotopias are disturbing, probably because they secretly undermine language, because they make it impossible to name this and that, because they shatter or tangle common names, because they destroy “syntax” in advance, and not only the syntax with which we construct sentences but also that less apparent syntax which causes words and things (next to and also opposite one another) to “hold together.”2

Heterotopias, understood as discontinuous conceptions of space, thus also pertain to the symbolic orders of language and discourse, to which I will return later when dealing with linguistic and, in particular, literary considerations on the relationships between theatre and society. However, in “Different Spaces,” Foucault outlines, above all, the various traits and types of real spaces, based on the premise that heterotopias exist in all human cultures. He distinguishes between “crisis heterotopias” of early cultures, that is, sacred or forbidden places where, for example, rites of passage took place, and modern societies' “heterotopias of deviation,” such as psychiatric hospitals and prisons. Foucault also sees heterotopias in the juxtaposition of several spaces in a single place—in the theatre, for example, where the stage can bring together a succession of otherwise irreconcilable places, or in the cinema, which can produce its own spatial fictions through the interaction of the auditorium, the projection room, and the screen. Heterotopias therefore frequently reveal themselves to be either “illusory places,” which sometimes even transform the reality of their surroundings, or “compensatory places,” in which an artificial and otherwise unparalleled order rules. Finally, heterotopias can break with the existing order of time, in the spacetime framework of a festival, for example.

Citing cemeteries, libraries, fairs, and gardens, Foucault also describes spaces in which the aforementioned aspects overlap or complement one another. The vast array of examples serves not so much to define a coherent classification as to illustrate the complexity and discontinuity of modern thinking on space. Particularly revealing is the manner in which Foucault likens culturally shaped spatial structures to a system of opening and closing that enables a specific balance between integration and exclusion, freedom and control. From this perspective, spaces should not be thought of as static, but always with reference to the potential for movement that they make possible. Accordingly, his essay ends with the ship, the heterotopia par excellence, which, considered a place of adventurous, dangerous, and also auspicious mobility, has stimulated imaginations from the sixteenth century onward: “a piece of floating space, a placeless place, that lives by its own devices, that is self-enclosed and, at the same time, delivered over to the boundless expanse of the ocean.”3 We could today identify as heterotopias a great many more spaces of circulation and transportation, as well as the electronic media, which, beyond the cinema, have established themselves as the predominant mechanisms and frameworks of perception. The term “heterotopia” can be further thought of in relation to the theatre, whose heterotopian effects are not limited to a represented juxtaposition of disparate spaces, but cover the entirety of its spatial layout—according to the changing relationship between stage and auditorium, which has become progressively more open, beyond the traditional box theatres. The separation of theatre from reality thus appears to be based on an opposition that is permeated or undermined by heterotopias.

Theatre occurs in spaces by enabling them to be experienced in a particular way or by creating them as such. It allows spaces to emerge in the minds of the onlookers by staging an existing structure or site, transforming it into the setting of other, imaginary spaces. However, the creation of theatrical situations between performers and spectators is possible anywhere—recent work with forms of theatre that take place outside of established theatre spaces has often confirmed this. These peculiarities of the theatrical constitution or experience of space demonstrate that the history of various forms of theatre spanning different eras must not be understood as the history of buildings or types of buildings only. Rather, it is a history of the spatial organization of different cultural practices, of encounters with and the mutual observation of people. That the constitution of spaces is always intimately bound to relations of power and control is one of the fundamental insights derived from Foucault's writings. Because spatially constructed heterotopias refer to structures of representation, they are commonly linked to linguistic-discursive heterotopias. This assumption is particularly significant for an analysis of the theatre conceptions that developed out of the crisis of traditional forms of representation at the turn of the nineteenth century.

When observed through the lens of Foucault's work, late eighteenth-century European theatre generally reveals itself to be a framework for staging the gaze as well as multiple strategies of (self-)representation. However, this traditional framework was increasingly adapted to the sociohistorical] changes set in motion by the transition from courtly culture to bourgeois culture. Methodologically, it is reasonable to assume that all aspects of heterotopias cited by Foucault can also be applied to theatrical spaces and situations. The discontinuous and disconcerting character of heterotopias underlined in The Order of Things can usefully inform the heuristic potential of the concept in relation to these developments in the theatre around 1800. It overlaps with Foucault's own description of implicit or explicit critiques of representation, and, instead of limiting itself to real places or buildings, also encompasses the analysis of discourse.

A new type of public sphere began to develop during the period under discussion here. The critique and replacement of inherited forms of representation, promoted by the philosophical and aesthetic redefinition of community and the public sphere constituted a central element of the Enlightenment project. The theatre, in particular, was held up as a school of ethics and morality, something which, in practice, it was both unable and unwilling to be.4 Jean-Jacques Rousseau's famous Letter to D'Alembert (1758) marked an important turning point in this regard, for it radically disputed the benefits of theatre for society, referring to its rather detrimental influence on life, especially in small communities or cities. At the same time, Rousseau's polemic was directed against the widespread theories of aesthetic effect and addressed the question of an active participation of the audience during public events. The idea of an autonomous festival of responsible citizens, set in opposition to courtly representation, turned the scene toward the outside, thereby conceiving theatre anew. Thus, in Rousseau's festival concept, utopian moments and the vision of a bourgeois public sphere combine with elements of heterotopia, the critique of representation, and the idea of a festive transgression.

Because of the manner in which it seized upon an old topos of antitheatrical positions and criticized the enclosure of entertainment and shady amusement in dark caves, Rousseau's text is exemplary of the changes to spatial conceptions in the second half of the eighteenth century.5 That it usually played in closed off, dimly lit, narrow, and poorly aired rooms was evidence, according to Rousseau, of the continuing link between the Enlightenment's bourgeois theatre and the loose morals of courtly culture. It was therefore of particular importance that the public festivals outlined in his counterproposal should take place under open skies.6 Rousseau's fondness for Schützenfeste and military traditions anticipated the representation of a new bourgeois, national community. This became obvious with Robespierre's application of Rousseau's ideas in the post-revolutionary festivals that simultaneously glorified the supreme being of abstract reason and demonstrated the military power of the new state order. These festivals must not be considered merely a betrayal or perversion of Rousseau's festival vision. For what really stands out in this distinctively theatrical staging of mass festivities in Paris is the fact that representative self-portrayal is also a prerequisite to the idea of a democratically constituted public sphere.

Jürgen Habermas's study The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere remains important in this regard, although it is based on a rather utopian model of negotiation and consensus. In a first step it reveals the historical conditions of the public sphere, focusing specifically on the emergence of and changes to a space of reflection that can be considered a requirement of democratic social orders. The model that serves as a starting point to Habermas's analysis is the representative public sphere that demarcated itself from the private sphere through the hierarchical order of representation. In the courts of baroque princes, the representative public sphere blossomed one final time before it began to split apart: “The bureaucracy, the military (and to some extent also the administration of justice) became independent institutions of public authority separate from the progressively privatized sphere of the court.”7 But what about the significance of theatre for a society that had started to replace the traditional forms of representation, which were reserved for a small stratum of the nobility and the church, with increasingly widespread processes of communication?

The German-speaking theatre of the Enlightenment was strongly devoted to the idea of a national community and to the principle of a discursive and reflective public sphere. This explains the depth of the disappointment caused by the failure of the idea of a national theatre—a failure that was already apparent in Lessing's Hamburgian enterprise, an early attempt to run a steady theatre on a shareholder base. The bourgeois theatre achieved its epoch-defining effectiveness and popularity not so much by idealistic visions but as an anthropologically founded practice of “human depiction,” characterized by psychology, compassion, and empathy, and able to transform theatre into a popular “laboratory of emotions.”8 At the same time, however, it prompted a resurgence of old anti-theatrical prejudices contained in new moral concerns. Theatre fervor and “theatromania” were deemed harmful excesses of affect and fantasy, an escape from reality and a sign of moral decay. The fundamental ambivalence of the bourgeoisie's attitude toward the theatre was finally expressed in the attempt to discipline the behavior of performers and spectators, and to channel the desire to transgress everyday conventions. The establishment of bourgeois theatre, determined by this program of discipline and self-control, already demonstrated the tension between utopia and heterotopia that has shaped theatre discourse ever since. Over the course of Enlightenment theatre policies, the theatre's own heterotopian potential for the festive transgression of daily life would be reduced or redeployed in favor of the ideal of a discursive public sphere. But this development was critically reflected, particularly in the theatre novels of the time.

ON THE SPREAD OF THEATRE IN BOURGEOIS SOCIETY, BETWEEN UTOPIA AND HETEROTOPIA

The development, outlined by Habermas, of the representative public sphere of the courts into a public sphere of reasoning presupposed the possibility of the bourgeoisie's own critical self-understanding, particularly in literary circles and journals. It reached its limits, however, with the functional appropriation of the media through advertising and politics, where “public opinion” was dependent on propaganda strategies, which were justified in the name of economic interests.9 Similarly, the bourgeois theatre's focus on emotional states and moral conceptions was accompanied by a growing commercialization. On the other hand, endeavors to found a bourgeois national theatre were still marked by court politics.10 This tense relationship, which was just as visible in the conflict between the content of bourgeois dramas and the theatre's persisting dependence on the courtly principle of representation, was given expression in the theatre novels of the late eighteenth century. Goethe's Wilhelm Meister and Karl Philipp Moritz's Anton Reiser are particularly instructive examples of the association of utopian and heterotopian elements in the theatre discourse of the period.11 The insight they provided into daily life behind the scenes questioned the prevalent utopian perception of theatre careers and made it possible instead to analyze them as a symptom of an insatiable urge for self-representation. These novels' protagonists flocked to the theatre as an institution that highlighted the discrepancy between bourgeois craving for recognition and social or, more specifically, economic reality. The plot always centers on enthusiastic young spectators seeking to become performers themselves, and who regard the theatre as a desirable job and way of life. The failure of these attempts to constitute an identity through self-representation anticipated the crises of national bourgeois culture. Not only was the enlightening, formative function of the theatre put into question but also the relation between theatre and festival as a relic of courtly representation. With the rise of new, bourgeois forms of ceremony and community, this representational structure was nonetheless adopted and, ultimately, idealized as the utopia of a solemn alliance of spectators.

“Bourgeoisie” in this context means a historically and culturally conditioned unity of different demographic groups that were related rather by mentality than by social or economic status.12 They also shared a fascination for the theatre, because it allowed them to assume foreign roles and test new modes of behavior. This switching of identities was part of and supported by a collective process, namely, the fleeting but still ceremonial and quasi-ritual communion of the audience. However, contrary to religious celebrations and the representation of symbolic power in courtly theatre, bourgeois theatre was meant to become the forum of a critical public expected to judge whatever was represented before it. To achieve this, it was necessary to control the various forms of transformation and transgression that were possible in the theatre, so that emotions could be used for moral purification and entertainment for ethical perfection. Accordingly, the novels depict the theatre as an ambivalent object of fascination, to which the crises of bourgeois existence were linked as much as the expectation of a life fulfilled by the glamour of public recognition. Theatre events of this period exhibited the paradoxical features of a festival that reflects and questions itself. This manifests the search for new and original forms of ceremoniality that should also enable a critical self-reflection of bourgeois manners and moral values. To achieve its theatrical self-formation, the bourgeoisie tried to get hold of the representational functions of courtly culture, while at the same time overcoming them with its own means, staging new forms of identity: “For the spectating as for the performing citizen, theatre can quite simply become a substitute to life, the world on stage a function of life.”13

This widespread phantasm lay at the heart of Goethe's novel and was the defining feature of Wilhelm Meister's famous letter on citizens and noblemen. In its most extreme form, the phantasm represented theatre as a hopeless existence, in which the dark depths of a destitute and immoral art could be identified. The letter argues that the nobleman is able to cultivate and preserve his personality because it ensures his authority. But this personality is only an appearance, for which, as a result of his state of dependence, he must pay. While the citizen lacks harmony because he has to isolate his personal qualities, the nobleman, for his part, is limited by the permanent obligation to represent himself publicly, and to be in service to a power quite distinct from private interests. Wilhelm wished to, at least on stage, “become a public person and to please and influence in a larger circle,” yet the fundamental premise of the argument with which he defends this intention is dubious.14 The phantasm of a public and glamorous festive appearance was a prominent feature of the new theatrical aesthetic that shaped the period at the turn of the nineteenth century well beyond the realms of stage performances. It is no coincidence that the festivals staged in the novel mostly turn into catastrophes as in many plays of the time. As a blend of literary genres that highlights the incalculable spread of theatre across society, the theatre novel can also be considered a heterotopia. However, if the utopian elements are put into question, this must not be mistaken for a complete rejection of theatre. It constitutes, rather, a sobering analysis of the altered conditions of representation.

The illusion-led empathy for an ideal subject described in the letter about citizens, noblemen, and actors proved to be the general and widely effective principle that underpinned the quest for representation, taking on a life of its own and abolishing the boundaries between appearance and being. The public person's dependence on the requirements of the (still representative) public sphere made the need for political and economic propaganda evident. The nation would also turn to staging as theatre in attempts to fulfill hopes of political unity and cultural identity. The panorama sketched by Goethe depicts an epoch in which there is no presence that is not already representation. Habermas's thesis, based on that letter in Goethe's novel, argues that Wilhelm's theatrical mission was bound to fail because the audience was already the carrier of a different, bourgeois public sphere “that no longer had anything in common with that of representation.”15 But this claim misses the point, for the new understanding of the public sphere still did not call into question the theatre's representation structures. Instead, the theatre novels of the time in fact described the spread of theatre across the whole of society, as it reached out to festivals and even parts of everyday life. Contrary to Habermas's interpretation of the novel, it appears more accurate to argue that the widespread dissolution of the boundaries between reality and theatre depicted by Goethe was in fact constitutive of the development of the bourgeois public sphere, bringing about the formation of a modern society of the spectacle.16 This perspective is highlighted in particular by the relationship between the heterotopias of literary theatre discourse and the heterotopian qualities of theatre spaces from that period.

Whenever Goethe's novel deals with theatrical events, he reveals his interest for the heterotopian constructions of fleeting, often festively arranged, stages and spectacles. This starts already with the mysterious play performed during Wilhelm's childhood at Christmas time in the door frame, on the threshold between two rooms; or the carefully decorated booth, finally destroyed by the angry rabble, where Wilhelm performed for the very first time; and even the chapel in which the Society of the Tower extravagantly staged Wilhelm's departure from the theatre. Precisely because of their significance as places of initiation, ritual inclusion or exclusion, the theatres described in the novel are always dissociated from real-life stages that are marked by their own theatricality. Of particular relevance is the prince's castle, comprised of two wings, one old and one new, the junction of which served as the theatre hall. It is here that a striking episode unfolds, providing an insight into the relation between court and theatre. From the very moment the count discovers Wilhelm and his theatre company, hires them for the upcoming birthday celebrations of the prince, and invites them to the castle, the fortunes of the actors take a steady turn for the worse. While magnificent festivities take place at the real court, they are sent away to the old, abandoned section of the castle, forced to get by without any support—a reversal of fortunes that “entirely destroyed their equanimity.”17

This unexpected twist marks the paradoxical nature of their false and eerie participation in courtly life; it points to the actors as representatives of representation: Their location—a space characterized by the immoral acts of the officers also quartered there and thus devoid of law and order—is the allegorical after-image of the castle, almost already in ruins. Goethe's intuition for staging heterotopias is visible in the manner in which he allows the theatre to constitute a threshold, in an empty hall, “which while still belonging to the old castle, was adjoined to the new one, and splendidly suited as a new theatre.”18 Wilhelm's aspiration to demonstrate his talent before a “noble audience,” has no chance in a performance dictated by courtly tastes. The disappointing reception of the staged celebration makes him realize that the actors, who had believed themselves to be at the center of courtly life, merely served as passing entertainment. Adjacent to the two very different parts of the building, the heterotopically constructed old festival hall confronts the various models of representation: the diversions of the court and the ambitious bourgeois art theatre, but also the military, with its own claims to representation and symbolic elevation.

HETEROTOPIAN LINKS BETWEEN THEATRE AND FESTIVAL

As demonstrated in the theatre novels and the vision of bourgeois festivals instigated by Rousseau, the representative festival was discredited as the epitome of absolutist splendor and power politics. This, however, made it all the more effective as a phantasm of bourgeois conceptions about a religiously and politically founded community of the nation. Festivals are heterotopias, not only because they require ephemeral spaces, as described by Foucault, but, more generally, as events based in a collective staging. As such, festivals include a potential for communality and excess, precisely those elements that bourgeois theatre had sought to eliminate in order to establish a critical discourse opposed to courtly theatre culture. But a theatre that wished to renounce all moments of festivity was in danger of ossifying in its function as a Bildungsinstitution or degenerating into a merely commercial entertainment. The counter-project, already anticipating modern twentieth-century conceptions, was again a heterotopia: the idea of theatre as an “other” festival, reflecting and enjoying itself. This festival idea was also guided by an increasing awareness about festival culture in Greek and Roman antiquity, the idealized backdrop of an inadequate present.19 Thus, around 1800, out of the many utopian visions and compromises made with everyday practices, designs for a new publicness of theatre emerged, in which the audience, far from serving as a forum for critical discourse, was at least to be confronted with itself. To understand this development, it is useful to take a quick look back at the theatre practice of this period, and specifically its pragmatic and ideological purposes.

The objectives of bourgeois theatre culture in Germany had three focal points:

The promotion of a sense of national identity through the performances of German dramas; the utilization of the stage as a “moral institution” at the service of a bourgeois-enlightened education; and the distinction of the national theatre as a middle-class establishment in comparison to both the courtly opera and the folk theatre of Italian tradition.20

The implementation of these aims in everyday theatre practice depended on the favor of the princes, the skills of the artistic director, and the receptiveness and tastes of the audience. Other important factors were the restriction of performance days, habitual economic difficulties, and censorship exercised by church and state authorities and internalized by writers, theatre artists, and spectators. The necessary compromises and considerations manifested themselves in “mixed” repertoires, adapted to the demands of the audience rather than to the high requirements of a morally and aesthetically founded Bildungsprogramm, as had been formulated by Schiller and Lessing.

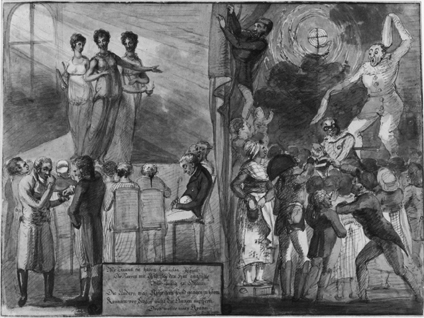

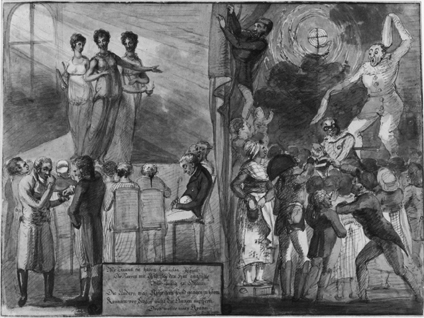

The spaces in which bourgeois theatre became established were frequently ballrooms (i.e., places of courtly representation) or mere wooden shacks, otherwise used for all kinds of spectacles for the amusement and distraction of the people. The publicly accessible theatre was therefore still strongly influenced by the conditions characteristic of folk theatre, which, with its Harlequin pantomimes, improvisations, and other spectacles, for a long time resisted attempts at reform and, through the assimilation of bourgeois tastes, retained the character of collective entertainment. As depicted in a caricature from around 1800 in Goethe's collection (see Fig. 10.1), literary theatre moved along the very border marked by the curtain—as a heterotopia oscillating between an exclusive claim to higher education and a culture of popular entertainment. In the picture, the rays

Figure 10.1 Sebastian Trifft, Two theatre scenes, around 1800, courtesy of Goethe-Nationalmuseum Weimar. Text insert: “Mir Traumt sie haben Comedia gspielt / Die Narren mit Geld sich den Hut ang'füllt / War lustig zu Schaun // Die Andern was Gscheiters seynd gangen zu hörn / Konnten vor Schlaf nicht die Augen aufspern / Drob wollte mirs Graun.” (I dreamt they played the comedia / The fools filled their hats with money / That was funny to see. // The others went for something more serious / Could hardly keep their eyes open, falling asleep / That was horrible.).

of Enlightenment may still shine on the antiquely dressed actresses, but they are not able to wake the saturated citizens from their slumber or to disturb the theatrical spectacle of the simple people, which is illuminated by its own, artificial light.

Even those acting companies that strove for an ambitious literary theatre could only survive on the income garnered in one location for a short time, before moving on elsewhere. In this respect, “refined” theatre was still some distance from a regular and orderly theatre establishment, while, on the other hand, its festive character was quite limited. In comparison, the transition from theatre to festival in courtly ballrooms was easy: The performances, with the princely person positioned either on stage or on a podium immediately before it, often retained the character of festive entertainment, while the subsequent celebrations with precise costumes and choreographies were theatrically staged as masked balls or dance performances and at the same time as representations of power. It was from this spatial, sociocultural, and aesthetic framework that the bourgeois theatre reforms had to begin. Not only the buffoon of improvised theatre had to be driven out but also the prince of courtly festivals. At stake was a reeducation of the audience, focusing first of all on their behavior and not yet on morals. Many disciplinary steps and measures were necessary for the theatre to become a place that might contribute to a public dialogue, at least indirectly via an analysis of private conflicts in a public auditorium.

That the demarcation of bourgeois theatre had to occur on two sides— against courtly theatre, on the one hand, and against the folk theatre of fairs and festival booths, on the other—was decisive for the question of the specific publicness of theatre at the turn of the nineteenth century. Accordingly, this publicness remained tied to heterotopias, in which otherwise established oppositions could blend together: the borders between inside and outside, public and private, sacred and secular, and also the distinction between higher and lower culture, education, and pleasure. After Rousseau, Diderot, and the Sturm und Drang (“Storm and Stress”) playwrights had rejected the cramped and gloomy conditions of bourgeois theatre, the longing to abandon the inadequate spaces and to move into a free and public life became a widespread subject of debate, which again focused on the performance traditions of ancient Greece.

But in particular Goethe's attempt to run the Weimar theatre according to the principles of classical aesthetics is revealing of the numerous compromises he had to accept due to the preferences of courtly society and the tastes of bourgeois audiences. One of the strategies he developed was to transform the representational tasks at court festivals into allegorical stagings, in which the arts and sometimes also the artists could be honored. At the same time, Goethe tried to enrich the theatre business with elements that were simultaneously festive and didactic. In doing so, he battled against the prevalence of illusion, by encouraging actors to adopt a distanced style and by repeatedly confronting the audience with itself. This idea of “mirroring” the audience must have been quite important to Goethe. Ever since his journey to Italy, he described this process with reference to the amphitheatre, which he had discovered in Verona:

Such an amphitheatre, in fact, is properly designed to impress the people with itself, to make them feel their best⋯. They are accustomed at other times to seeing each other running hither and thither in confusion, bustling about without order or discipline. Now this manyheaded, many-minded, fickle, blundering monster suddenly sees itself united as one noble assembly, welded into one mass.21

Contrary to the custom in Verona, Goethe chose not to employ the word “arena” (sand area, place to fight) to denote the monumental construction of AD 30, favoring the term “amphitheatre,” which, according to a traditional derivation, recalled the joining of two semicircular theatres. In opposition to the central perspective offered by the spatial arrangement of box theatres, his objective was to highlight and make use of the potential of the oval architecture to confront the people in the theatre with themselves. Also in the “Diary of the Italian Journey,” Goethe noted that the people lived in the street and were already accustomed to observing one another. What was specific to the amphitheatre, he believed, was the self-perception of a usually chaotic, heterogeneous people as an organized and whole body. Therefore he interpreted this deception as a means to make the people “feel at their best.” The unity of the masses, seemingly “animated by a single spirit,” turns out to be an effect of representation: The people represent themselves, staged through the framework of the architecture.

This spatial framework of mirroring the audience so fascinated Goethe that he also wished to introduce it to the theatre spectators in Weimar. Evidence of this can be found in letters to Schiller and in his art-theoretical dialogue “On Truth and Probability in Works of Art” (1797). Here, he defended the opera décor of the painter Giorgio Fuentes in Antonio Salieri's opera Palmyra, where, during a decisive scene, the audience was confronted with spectators painted on the backdrop:

In a German theatre there was a sort of oval amphitheatre, with boxes filled with painted spectators, apparently engrossed in what was going on below. Many of the real spectators in the pit and the boxes did not like this at all; they took it amiss that something so untrue and improbable should be foisted upon them.22

As becomes obvious in the context of the dialogue, this mirroring had the effect of a disruption, not because the painted spectators on stage were unrealistic but because the conditions of operatic reception of the time were themselves dependent on an illusory closure. In opposition to this, the break with illusion explicitly defended by Goethe was yet another opportunity for mirroring the audience and reminding it of the theatrical situation. Goethe demanded and occasionally succeeded in introducing to the reality of the theatres of his time what he discovered as a model of publicness in the amphitheatre in Verona and later in the highly theatrical people's festival of the Roman Carnival. This points to a politics of space, which was turned against the then nascent illusionism, and which is as relevant to us today as the dissolution of the theatrical boundaries reflected in Goethe's Wilhelm Meister novel. In this regard, also the mirroring of the audience acquires a particular significance as a heterotopian experience of space. The mirror connects the ideal placelessness of utopias to the disturbing spatial experience of heterotopias as they are described by Foucault: “I think that between utopias and these utterly different emplacements, these heterotopias, there must be a kind of mixed, intermediate experience, that would be the mirror.”23 One sees oneself where one is not (that would be the utopia), only to be reminded where one is in reality but at the same time where one is missing; that is where the experience of heterotopia takes place.

In the theatre of the turn of the nineteenth century, bourgeois society began to mirror itself, not just individually, but also collectively, as a concatenation of different stagings. What can be described during this period as critique of representation pointed beyond the practice of theatre, toward the structures of representation in social life. In this context and with a skeptical look at the ideal image of a critically reasoning public sphere, the theatre novels addressed the potential, immanent in theatre, for events of excess and festive transgression. Thus, around 1800, they became spaces of heterotopian experience, depicting theatre in the context of real everyday life, and, conversely, portraying the places of bourgeois life in light of its increasing theatrical staging. The manner in which these novels, and sometimes also stage performances, succeeded in mirroring the audience—cutting through the general desire for illusion—reinforced the disappointment of bourgeois utopias. Therefore as well, the spatial qualities of heterotopias as outlined by Foucault can be applied to the theatre of that era. The perspective opened up by theatre novels hints at the conclusion that heterotopias can themselves possess a theatrical quality, which encompasses their representative, discursive, and transformative potential: “realized utopias in which the real emplacements, all the other real emplacements that can be found within the culture are, at the same time, represented, contested, and reversed, sorts of places that are outside all places, although they are actually localizable.”24

NOTES

1. Michel Foucault, “Different Spaces,” in James D. Faubion (ed.), The Essential Works of Foucault, vol. 2: Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology (New York: Fhe New Press, 1998), 175–185, 176.

2. Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (Fondon: Routledge, 2002), xix.

3. Foucault, “Different Spaces,” 184–185.

4. Cf. Wolfgang Bender (ed.), Schauspielkunst im 18. Jahrhundert (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1992); Roland Dreßler, Von der Schaubühne zur Sittenschule: Das Theaterpublikum vor der vierten Wand (Berlin: Henschel, 1993); Erika Fischer-Lichte and Jörg Schönert (eds.), Theater im Kulturwandel des 18. Jahrhunderts (Göttingen: Wallstein, 1999). For publications in English cf. Walter Horace Bruford, Culture and Society in Classical Weimar: 1775–1806 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1962) and, by the same author, Germany in the Eighteenth Century: The Social Background of the Literary Revival (Cambridge: University Press, 1965). See also Simon Williams (ed.), A History of German Theatre (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008).

5. Cf. Jonas Barish, The antitheatrical prejudice (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981).

6. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, “Letter to D'Alembert,” trans. Allan Bloom, in Allan Bloom, Charles Butterworth, and Christopher Kelly (eds.), Letter to D'Alembert and Writings for the Theatre (Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 2004), 251–352, 342. Cf. in more detail and also concerning the reception of Rousseau's letter in the German-speaking world my investigation Das andere Fest: Theater und Öffentlichkeit um 1800 (Frankfurt am Main: Campus, 2008), 140–187.

7. Jürgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, trans. Thomas Burger (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989), 12.

8. Cf. Rainer Ruppert, Labor der Seele und der Emotionen: Funktionen des Theaters im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert (Berlin: Edition Sigma, 1995).

9. Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, 177.

10. Cf. Reinhart Meyer, “Das Nationaltheater in Deutschland als höfisches Institut,” in Roger Bauer and Jürgen Wertheimer (eds.), Das Ende des Stegreifspiels—Die Geburt des Nationaltheaters (Munich: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 1983), 124–152. See also Marvin Carlson, Goethe and the Weimar Theatre (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1978) and Francis J. Lamport, German Classical Drama: Theatre, Humanity and Nation; 1750–1870 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

11. Cf. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Wilhelm Meister's Theatrical Calling, trans. John R. Russell (Columbia, SC: Camden House, 1995), and Karl Philipp Moritz, Anton Reiser: A Psychological Novel, trans. John R. Russel (Columbia, SC: Camden House, 1996).

12. For an analysis of the German term “Bürgertum,” cf. Michael Maurer, Die Biographie des Bürgers: Lebensformen und Denkweisen in der formativen Phase des deutschen Bürgertums (1680–1815) (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck, 1996), 16ff.

13. Cf. Rudolf Selbmann, Theater im Roman (Munich: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 1981), 19, and Eckehard Catholy, “Die geschichtlichen Voraussetzungen des Illusionstheaters in Deutschland,” in Eckehard Catholy and Winfried Hellmann (eds.), Festschrift für Klaus Ziegler (Tübingen: M. Niemeyer, 1968), 93–111. See also Frederick Burwick, Illusion and the Drama: critical Theory of the Enlightenment and Romantic Era (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1987).

14. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship and Travels, trans. Thomas Carlyle (London: Chapman and Hall, 1834), vol. 2, 10.

15. Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, 14.

16. For this whole development cf. Guy Debord, The Society of Spectacle (La société du spectacle, originally published in 1967), trans. Ken Knabb (London: Rebel Press, 2004).

17. Cf. Goethe, Wilhelm Meister's Theatrical Calling, book III, chapter 3.

18. Ibid., book III, chapter 4.

19. Cf. more detailed Primavesi, Das andere Fest, 233–354.

20. Horst Hartmann, “Das Mannheimer Theater am Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts,” in Anke Detken, Thorsten Unger, Brigitte Schulze, and Horst Turk (eds.), Theater und Kulturtransfer II (Tübingen: Narr, 1998), 123–134, 124.

21. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Italian Journey: 1786–1788, trans. W.H. Auden and Elizabeth Mayer (New York: Schocken Books, 1968), 35.

22. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, “On Truth and Probability in Works of Art,” in John Gage (ed. and trans.), Goethe on Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980), 25.

23. Foucault, “Different Spaces,” 178–179.

24. Ibid., 178.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barish, Jonas, The antitheatrical prejudice, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981.

Bender, Wolfgang (ed.), Schauspielkunst im 18. Jahrhundert, Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1992.

Bruford, Walter Horace, Culture and Society in Classical Weimar: 1775–1806, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1962.

Bruford, Walter Horace, Germany in the Eighteenth Century: The Social Background of the Literary Revival, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1965.

Burwick, Frederick, Illusion and the Drama: Critical Theory of the Enlightenment and Romantic Era, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1987.

Carlson, Marvin, Goethe and the Weimar Theatre, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1978.

Catholy, Eckehard, “Die geschichtlichen Voraussetzungen des Illusionstheaters in Deutschland,” in Eckehard Catholy and Winfried Hellmann (eds.), Festschrift für Klaus Ziegler, Tübingen: M. Niemeyer, 1968, 93–111.

Debord, Guy, The Society of Spectacle (La société du spectacle 1967), trans. Ken Knabb, London: Rebel Press, 2004.

Dreßler, Roland, Von der Schaubühne zur Sittenschule: Das Theaterpublikum vor der vierten Wand, Berlin: Henschel, 1993.

Fischer-Lichte, Erika and Schönert, Jörg (eds.), Theater im Kulturwandel des 18. Jahrhunderts, Göttingen: Wallstein, 1999.

Foucault, Michel, “Different Spaces,” in James D. Faubion (ed.), The Essential Works of Foucault, vol. 2: Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology, New York: The New Press, 1998, 175–185.

Foucault, Michel, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences, London: Routledge, 2002.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von, Italian Journey: 1786–1788, trans. by W.H. Auden and Elizabeth Mayer, New York: Schocken Books, 1968.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von, “On Truth and Probability in Works of Art,” in John Gage (ed. and trans.), Goethe on Art, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980, 25–30.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von, Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship and Travels, trans. Thomas Carlyle, London: Chapman and Hall, 1834.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von, Wilhelm Meister's Theatrical Calling, trans. John R. Russell, Columbia, SC: Camden House, 1995.

Habermas, Jürgen, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, trans. Thomas Burger, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1989.

Hartmann, Horst, “Das Mannheimer Theater am Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts,” in Anke Detken, Thorsten Unger, Brigitte Schulze, and Horst Turk (eds.), Theater und Kulturtransfer II, Tübingen: Narr, 1998, 123–134.

Lamport, Francis J., German Classical Drama: Theatre, Humanity and Nation; 1750–1870, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Maurer, Michael, Die Biographie des Bürgers: Lebensformen und Denkweisen in der formativen Phase des deutschen Bürgertums (1680–1815), Göttingen: Vandenhoeck, 1996.

Meyer, Reinhart, “Das Nationaltheater in Deutschland als höfisches Institut,” in Roger Bauer and Jürgen Wertheimer (eds.), Das Ende des Stegreifspiels—Die Geburt des Nationaltheaters, Munich: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 1983, 124–152.

Moritz, Karl Philipp, Anton Reiser: A Psychological Novel, trans. John R. Russel, Columbia, SC: Camden House, 1996.

Primavesi, Patrick, Das andere Pest: Theater und Öffentlichkeit um 1800, Frankfurt am Main: Campus, 2008.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques, “Letter to D'Alembert,” trans. Allan Bloom, in Allan Bloom, Charles Butterworth, and Christopher Kelly (eds.), Letter to D'Alembert and Writings for the Theater, Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 2004, 251–352.

Ruppert, Rainer, Labor der Seele und der Emotionen: Funktionen des Theaters im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert, Berlin: Edition Sigma, 1995.

Selbmann, Rudolf, Theater im Roman, Munich: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 1981.

Williams, Simon (ed.), A History of German Theatre, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.