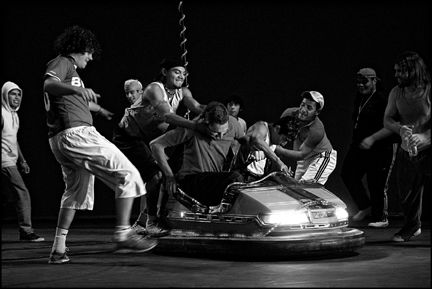

Figure 11.1 Marat, What Became of Our Revolution? (Marat/Sade) by Volker Lösch, Hamburger Schauspielhaus, © A.T. Schaefer.

Benjamin Wibstutz

Translation by Michael Breslin

and Saskya Iris Jain

Hamburg, December 4, 2008, 9:45 p.m.: The audience in the theatre was going wild. There was whistling and jeering. Some heckled raucously. At the end, waves of rousing applause thundered through the theatre, as though at a sporting event. On stage stood a chorus of twenty-four poor or unemployed individuals in dripping wet raincoats, who, during the final scene, had loudly proclaimed the names, office addresses, and estimated fortunes of the Hanseatic city's twenty-eight richest citizens:

Number 31 on Manager Magazin's 2008 rich list: Klaus Michael Kühne, Kühne und Nagel Logistics. 29, Ferdinand St., 20095 Hamburg. Net Worth 4.1 billion euros. Number 24 on Manager Magazin's 2008 rich list: under the threat of a temporary injunction issued on October 24, 2008, this name cannot be read out. Net Worth 4.5 billion euros. Number 5 on Manager Magazin's 2008 rich list: under the threat of a temporary injunction issued on October 24, 2008, this name cannot be read out. Net Worth 8.1 billion euros.1

As every year, the list was published some weeks earlier in the aforementioned business magazine under the heading “The 300 Richest Germans.” Even before the premiere, its planned recital in the theatre provoked a cleverly calculated scandal. Careful to avoid legal proceedings, the theatre chose not to read out all of the names and, where relevant, instructed the chorus to refer to the lawyer's letter instead.

This restriction evidently did nothing to dampen the explosive nature of the scene. On the contrary, it seemingly made the audience revel all the more in this “poor man's chorus,” as if the spectators hoped, as a review in the weekly newspaper Die Zeit suggested, “to chain their own rage and exuberance to the steepness of the sums revealed by the chorus, so that they might, eventually, go through the roof together.”2

The performance in question was Volker Lösch's production of the Peter Weiss play Marat/Sade, which was also staged at the prestigious festival Theatertreffen in 2009, among other places. Marat, What Became of Our Revolution? is the title of Lösch's adaptation of the play, for which, as so often in the past, he assembled a chorus of poor and unemployed people. “Away with money” and “Hamburg must burn” were cries that sounded from the stage as the performance neared its end. By proclaiming the names and addresses of the city's richest people, the scene was indirectly referring to the historical figure of Jean-Paul Marat, who published all the names of the revolution's enemies in his radical newspaper Ami de peuple. The reaction of the audience was evidence enough that at least one aspect of the director's concept had the desired effect: For a moment, art moved into the background and the theatre as a political space came to the fore. It is here that the revolution is acted out and the uprising of the poor rehearsed. The spectators cheer as those “superfluous” to society or excluded from it rebel against social injustice and inequality. Yet, it is this very cheering that leads us to doubt whether the theatre, in this instance, really does represent a political space. Would this middle-class Hanseatic audience revel in a real uprising of the poor? Would a production of this sort be invited to the Theatertreffen if it had real political potency?

It is obviously not possible to conclusively determine the true political potential of this or similar types of performance, nor is it the main concern of this chapter. Rather, I hope to draw attention to a phenomenon in contemporary theatre that has been observed in a variety of venues across Europe since the turn of the century: largely middle-class audiences rejoicing in the presence on stage of the socially and culturally underprivileged, who, all of them lay actors, play themselves and

Figure 11.1 Marat, What Became of Our Revolution? (Marat/Sade) by Volker Lösch, Hamburger Schauspielhaus, © A.T. Schaefer.

embody the marginalized classes of contemporary society: The homeless, asylum-seekers, pensioners, the disabled, the unemployed, and the sick move into the theatrical spotlight, leaving their social anonymity behind. This type of theatre, because of its alterity, is perceived and understood by the viewing public as inherently political. But the political agitation is not always of the nature displayed by Volker Lösch's chorus of poor and unemployed individuals. Alongside Lösch, we can point to a range of different directors, such as Pippo Delbono, Romeo Castellucci, Rodrigo Garcia, Peter Sellars, Christoph Schlingensief, Constanza Macras, and Rimini Protokoll, each with a different approach to mise-en-scène, but all with one thing in common: their intention to make underprivileged members of society visible.

These postdramatic theatrical experiences of the socially underprivileged are underpinned by two conceptions that have, time and again, had a profound effect on the history of theatre. The first, particularly apparent in Lösch's productions, concerns the promising intention of creating politics by employing the stage as a place of utopian action. In this respect, theatre as heterotopia can provide a political counter-site to society; it becomes another space, laboratory-like, which, because of its liminal space-time framing, its system of opening and closing, can generate a state of exception that need not pose a veritable threat to places and orders outside the performance space. According to the second claim, the theatre is simultaneously seen as a space of others, in which the underprivileged, representing the socially and culturally “other,” take the stage as protagonists and thereby enjoy a presence to which they are not entitled in their everyday social life outside of the theatre. In this chapter, I focus on this old, apparently yet again very relevant, dual promise of the theatre to be at once an other space and a space of others. By formulating a theoretical perspective, I will address a series of general questions, which contemporary political theatre must ask itself, concerning the potentials and risks associated with such a promise.

How strange, indeed. What is it about the wonderfully simple mechanisms of a theatre scandal that proves so effective? Why was it that, upon learning their names were to be recited on stage, the millionaires unleashed their lawyers on the theatre production? The answer is as straightforward as it is complex: Theatre is never just an art; it also always represents a real and public space of social occurrences. For the super-rich, the scandal lies not so much in the fact that an already published list of their fortunes is to serve as performance material in an artistic setting. What is truly scandalous is the real and public nature of the action, which, evening after evening, brings together a group of poor and unemployed individuals to recite the list in chorus before several hundred cheering spectators. Clearly this is the moment when the millionaires concerned confuse theatre with social reality, something all the more understandable given that a performance takes place in actual space and time between spectators and performers. However, this socially engendered performativity is only one of theatre's traits. To be art, every performance requires a space-time marking and a system of opening and closing that separate it from everyday social life. The encounter between spectators and performers at the same place and time, for a performance that has a marked beginning and an obvious end, in itself establishes a certain distance from daily life. Therefore, there is no doubt in the minds of the spectators present at Volker Lösch's Marat that the poor people's uprising on stage is nothing other than theatre. By contrast, a staged and politically covert action executed in public, along the lines, for example, of Augusto Boal's method of “invisible theatre,” can be described as theatrical, but not as a theatre performance, precisely because the spectators do not recognize the performance as such.3 The theatre's visible space-time boundaries reveal its Janus-faced character; it cannot be reduced to one of the two dimensions, but always encompasses both the aesthetic and the social space. This ambivalence of theatrical space forever leads to difficult legal, ethical, and political questions that seek to determine the precise conditions under which performances can be judged as being either art or a social, public event. A theatrical event can only be regarded as art if it establishes certain boundaries vis-à-vis the outside, framing its performance as “impact-reduced” (konsequenzvermindert). With this term, the theatre scholar Andreas Kotte proposes distinguishing theatre from those games, contests, and cultural performances whose actions have effective consequences.4 But does “impact reduction” still apply when actual unemployed people read out the names and addresses of real millionaires? The legal intervention of the rich at least demonstrates that assessing the consequences is more difficult when, despite the boundaries laid down, social reality reenters through the theatre's backdoor.

It is generally true that the space-time demarcation established by a performance provides theatre with the opportunity to suspend certain everyday rules and laws. Characters can, for example, die on stage, only to rise again as actors to the applause of the audience. Different places and times can be represented on stage one after the other, which can fictionalize the space in this way or that. The performance can charge the theatrical space with a particular atmosphere or energy, giving it the appearance of a space of collective experience, transformed by both spectators and performers.

It is because of this ability to constitute an exceptional space, which is subject to other rules and conditions and separated from everyday social life, that theatre can be considered a heterotopia. Michel Foucault believed heterotopias to represent specific, institutionally grounded places, which differ from other places in our societies due to their space-time relationship. These are places

that are designed into the very institution of society, which are sorts of actually realized utopias in which the real emplacements, all the other real emplacements that can be found within the culture, are, at the same time, represented, contested and reversed, sorts of places that are outside all places, although they are actually localizable.5

For Foucault, the theatre, in addition to museums, gardens, cemeteries, prisons, festivals, and yearly fairs, represents such a heterotopia, particularly in light of its ability to bring onto the stage “a whole succession of places that are unrelated to one another.”6 The heterotopian quality of the theatre therefore lies, according to Foucault, in the capacity it has for representation. Viewed from today's perspective, his description reveals a rather traditional dramatic understanding of theatre—hardly surprising in a text from 1967. But the other types of heterotopias cited by Foucault suggest that theatre and performance actually exhibit far more heterotopian qualities than simply the manner in which they represent various places on stage. In fact, the theatre can be linked to almost all the types of heterotopia listed by Foucault.

He refers, for example, to certain spaces that are also heterochronies. These either accumulate time, as in museums and libraries, or, in the manner of a festival, highlight its peculiar fleeting and transitory nature. It is not difficult to demonstrate that the theatre displays principles belonging to both of these time-specific heterotopias. On the one hand, a theatre performance, much like a museum, is capable of representing different times and layers of time simultaneously and of linking them to one another. Various temporalities represented on stage can be juxtaposed to the present experience of an event in the here and now: one or several moments of the action, but also references to the author's period, allusions to earlier productions, or citations from other works of art or historical events. All of these aim to trigger the spectators' recognition mechanisms. The audience in Lösch's production of Marat/Sade is thus confronted not only with the different periods of the French Revolution, of de Sade's Napoleonic time, and of the present (which are all features of Peter Weiss's drama plot), but also with other icons of revolutionary history, such as Lenin, who floats down upon the unemployed chorus with unmistakable class-war posturing, or, in another scene, Che Guevara, who dances a tango with de Sade.

On the other hand, due to their specific temporality, performances have been repeatedly tied to festivals over the course of theatre history. They therefore also correspond to the second type of heterochrony pointed to by Foucault. It has been sufficiently shown that European theatre emerged in antiquity from the ritual and festive practices employed by the cult of Dionysus.7 Theatrical performances were also closely linked to festivals in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, as demonstrated by the spiritual passion plays and urban carnival plays, which, as heterochronies, granted participants a “state of exception” of limited duration.8 The idea of theatre as a communal festival can also be found in Richard Wagner, and in the early twentieth-century avant-garde conceptions of the German theatre directors Max Reinhardt and Georg Fuchs, among others.9 Finally, modern theatre festivals, the majority of which were founded after World War II, have continued to cultivate this close bond between theatre and festival.

Evidence that present-day theatre can be understood as heterochronical, even outside of a festive setting, is hinted at by Hans-Thies Lehmann's observation that many contemporary directors (for example, Volker Lösch in Marat/ Sade) choose not to include an intermission. The logic behind this is based not on “the concern to preserve the illusion, but on the protection of a separate and autonomous time frame of experience,”10 which marks a rupture with the normal time of daily life. In a similar vein, crossing the threshold into the theatre itself and conventions such as the admittance into or the darkening of the auditorium mark an “accentuated time of initiation,”11 differentiating it from everyday life and thus enabling reflection on another time.

It is no coincidence that the terms “threshold” and “initiation” bring to mind the crisis heterotopias also cited by Foucault, which, as closer inspection makes clear, are likewise bound to theatre. These are privileged, sacred, or forbidden places reserved for people who find themselves in a biological state of crisis.12 The places mentioned by Foucault thus bear a certain relation to the rites of passage of premodern societies; such is the case with the limbo state of honeymooners, or with the boarding school, where, far removed from the family sphere, pubescent boys were allowed their first expressions of male sexuality. These heterotopias are evidently indirectly or directly related to places of the transformative liminal phase which Arnold van Gennep and, later, Victor Turner classed as the middle phase of rites of passage. According to Turner, this liminal phase can be understood as a cultural ludic space in which values, norms, and symbolic orders are negotiated and confirmed, and through which “new ways of acting, new combinations of symbols” are made available.13 The subjects who consummate this three-stage ritual find themselves exposed, during this middle liminal phase, to a labile intermediary existence beyond norms and social orders.14

Turner's theory of liminality prompted Erika Fischer-Lichte to define the aesthetic experience during performances as a liminal experience in which the recipients once again find themselves in an “in-between” threshold state.15 Understood in this way, a performance can provoke destabilizing moments of self-perception or perception of others, in which dichotomic orders, such as fiction and reality, presence and representation, activity or passivity are suspended. During a performance, it is also possible for theatre spectators to experience a transformation, making them feel like momentary members of a festive community, for example, or by which, from passive onlookers, they become active participants in an event—the Hamburg staging of Marat/Sade is typical in this respect. The fundamental difference between liminality in the theatre and liminality in the ritual is, of course, that only in the most exceptional cases do the transformations caused by the aesthetic experience endure once the performance is over. The third phase that theatre goers pass through is normally nothing other than the reversal of the separation phase, which implies the reintegration into everyday life unaccompanied by the new identity or consummated transformation that marked the ritual experience.

This, therefore, is the most significant difference between the theatre and a rite of passage. Just like Foucault's crisis heterotopias, however, the former displaces the liminal, destabilizing ludic space into a socially isolated sphere, which still remains institutionally grounded in society. For both Foucault and Turner, a given culture's specific liminal spaces establish visible boundaries vis-à-vis everyday social life, shifting the crisis or the state of exception into an “outside” space of society, thus opening up room for negotiating established orders without ever truly threatening them. In this secluded sphere, other, more subversive laws and norms apply than those which more commonly perform the functions of stabilizing social orders. If one refers these basic conditions of heterotopia back to the scandal that broke out in the Hamburg theatre, the contradiction between the boisterous spectators and the lawyers' letters recited on stage becomes all the more extreme. For, while the lawyers treated the performance as if it were a part of social reality, it did not occur to any of the spectators to spontaneously demonstrate upon exiting the theatre, or to start chanting protests on the steps of the job center or of the millionaires' offices the following morning. Clearly, the audience recognized and championed the “aesthetic difference” of the theatrical performance; one could even say that this “difference” changed the spectators' attitude and behavior toward the performers on stage and temporarily broke down the barrier between stage and auditorium. The very act of crossing the threshold again, but this time in the opposite direction, that is, leaving the auditorium behind, shifts the performance event into a past belonging to a distant, other space, which has little in common with the individually led social life of the everyday. And yet, as demonstrated by the millionaires' reaction, it would be wrong to ignore the theatre's potential to provoke unrest and act as a counter-site to society, prompting the custodians of order to intervene at times when the theatre appears overly inclined to meddle in political and social affairs. The political potential of theatre as heterotopia is therefore no less ambivalent than the space of the theatre itself. On the one hand, even in its postdramatic forms, the theatre has shown that it is necessarily impact-reducing; spectators and actors are usually capable of distinguishing between theatre and political events. On the other hand, the theatre's utopian moment lies precisely in its ability to create or represent events that cannot take place within everyday social life, or to confront elements of social and political reality with forms of artistic reflection and imaginary utopian orders. Consequently, the potential of the other space should be sought less in its immediate political influence over society, and far more in its quality as a place of reflection and confrontation. In this sense, director Volker Lösch should be thankful for the millionaires' reaction. Their objection to the performance challenged the aesthetic difference of a staged revolution, transforming the theatrical space into a contradictory and tension-laden in-between of the aesthetic and the social, revealing its political moment.

The importance of crisis heterotopias and rites of passage has, to a great extent, been lost in our society. They have been replaced, according to Foucault, by modern-day heterotopias of deviance. Sanatoriums, retirement homes, psychiatric clinics, homes for the disabled, and prisons are today heterotopias in which individuals experiencing a crisis or who deviate from the norm are placed. These are precisely the same socially disadvantaged individuals who today, increasingly, again find themselves on the theatrical stages. It is in fact frequently the case in the works of those producers consulted over the course of my research that the theatre, for as long as the production lasts, adopts a care function that would otherwise rest with a home or with one of the other heterotopias of deviance. Theatre and performance groups that work with disabled persons allow them a release, for a limited time, from their care homes; asylum seekers, exceptionally, are able to work as actors; and the unemployed individuals that make up the chorus are temporarily kept away from the job center. Does the theatre itself become a heterotopia of deviance when, over the course of a production, it cares for the socially underprivileged?

The idea of deploying theatre as a space of others is, in any case, as old as the theatre itself. Tellingly, the oldest surviving play from ancient Greece relates the naval battle of Salamis from the viewpoint of the foreigners, namely the defeated Persians. Against this backdrop, it is merely the combination of politico-emancipatory claims and their postdramatic execution that is new in the examples from contemporary theatre. Notwithstanding the manner of the production, ancient theatre is still nowadays regularly invoked as a model. A statement by the philosopher Alain Badiou from his “Theses on Theatre” can serve to illustrate this reactivation of an old principle:

The duty of the theatre is to recompose upon the stage a few living situations, articulated on the basis of some essential types. To offer our own time the equivalent of the slaves and domestics of ancient comedy—excluded and invisible people who, all of a sudden, by the effect of the theatre-idea, embody upon the stage intelligence and force, desire and mastery.16

What is clearly at stake for Badiou is theatre's utopian moment, which, on behalf of the underprivileged, reveals itself as an idea on stage. His argumentation is philosophical and based, therefore, on the general conditions of theatre as an art form rather than on specific theatre productions and the manner in which laypersons represent themselves. That contemporary directors who work with the socially underprivileged also have the principle of ancient theatre as a space of others as a reference point was made clear in a 2004 television interview with Peter Sellars. As the American director, who, that year, let young refugee children take the stage for Euripides's The Children of Herakles, explained:

The Greeks invented theatre as part of the government. Like the judiciary and the legislative you have the theatre. The Greeks made this giant ear in the side of a mountain and they called it a theatre and they put a seat for every single citizen who could vote. Now that means of course only men because democracy was a wonderful thing unless you were a woman or a slave. And so meanwhile every one of the Greek plays is about women, children and foreigners: the people who were not allowed to vote. And so it was a place where the people you never hear from in the senate finally can speak. And it was this idea that you can't be a citizen until you hear these people speak also. And your voting will be informed not just by the senate but by the theatre where the microphone is given to women, to slaves, to foreigners and to children⋯. They [the refugees] are here invisibly, silently and so for me one of the most important things is that people should know them. People should hear from them and I look at someone like Mamadi [one of the children] as a future Nelson Mandela, as one of those Gandhi-figures who can explain the East to the West; who can explain the West to the East; who can move back and forth across cultures; who is coming to us as a messenger of something we need to learn about⋯. It's very important that this person who is at the moment hidden away on the top floor of a refugee centre in a very limited life where all the things he is not allowed to do—it's a very long list—I would like to say that for three nights, hundreds of people will applaud his existence.17

Some of these assertions are certainly problematic and historically inaccurate,18 but it is worth drawing attention to two points. First, Sellars's primary concern, it would seem, is to make the invisible visible again. His remarks recall certain theoretical debates in philosophy, such as Axel Honneth's account of social invisibility, or the relation established by Jacques Rancière between politics and a disagreement on the “distribution of the sensible,” which stems from disregarding the sans-part (those without a part), whose speech is not recognized as such, but usually perceived merely as noise.19 Second, Sellars's remarks show that, although his theatre may seek to encourage understanding and recognition, as well as applause, for the underprivileged, it cannot be his objective to politically negotiate the demarcation between the audience and the “others.” When Sellars compares the child refugee on stage to the role of an ambassador between different worlds, he seems less to question the division between the rulers and the disadvantaged, or between refugees and theatre spectators, than to use the heterotopia of theatre for an encounter with the other. This type of social encounter is utopian in daily life, because, in the real world, the children are banished to their camps or homes, with no contact to social life. By declaring itself a site of exception and making this unlikely encounter possible, theatre provides spectators with access to the heterotopias of deviance and their inhabitants. Although one might subscribe to Giorgio Agamben's description of this relation of exception as a “relation of ban,” it remains open whether the performance does, in truth, manage to overturn the banishment:

He who has been banned is not, in fact, simply set outside the law and made indifferent to it, but rather abandoned by it, that is, exposed and threatened on the threshold in which life and law, outside and inside, become indistinguishable. It is literally not possible to say whether the one who has been banned is outside or inside the juridical order.20

These are the very same features that affect the theatrical space as heterotopia. In comparison to the one at work in the heterotopia of deviance, the system of opening and closing in the theatre is less severe, rendering any comparison with Agamben's principle of the camp disproportionate. Nevertheless, the heterotopia of the theatre runs the risk of merely simulating other relations or encounters and, ultimately, confirming the old boundaries and divisions. This does not imply that the theatre as a place, aided by these actors, is unable to instigate a debate about the segregation and the conditions of refugees and the unemployed. But Sellars's remarks— and much more clearly, I should note, than his successful production— underline the danger of theatre taking the stage as simply one heterotopia among many, in which the “others” can perform and in which, as Agamben writes, circumstances permitting, they continue to be displayed and exposed—the only difference being the applause they receive on these three evenings. That the sans-part are made visible or that an encounter with them is made possible, in no way means that the performance leaves a trail of consequences in its wake or provokes a fundamental reflection about politics and the social sphere. For the “expendable class,” as the sociologist Gerhard Lenski once termed the beggars, outlaws, criminals, and all others deemed superfluous to society,21 there is always the danger that, when made visible on stage, they will degenerate into objects of pity or exoticism, which would turn on its head Alain Badiou's previously quoted call for the embodiment of intelligence and force, desire and mastery.

It may therefore be worthwhile to ask to what extent the respective forms of this theatre of the socially underprivileged seek to act either as a heterotopia of deviance or as a crisis heterotopia. The choice between the two determines the course followed with regard to one of two policies: The former sees greater potential in the possibility of an encounter, while the latter favors the liminal space of the crisis.

In concluding my considerations on contemporary theatre as heterotopia, I would like to offer one further example, which, in my opinion, successfully follows a third path that is different from Volker Lösch's political agitation and that avoids the hidden danger of an aesthetics of pity identified in Peter Sellars's remarks. The production in question, Cruda, vuelta y vuelta, al punto, chamuscada by the Spanish director Rodrigo Garcia, was shown at the Festival d'Avignon in 2007. Together with one actor, a group of young Argentineans took the stage. They were former delinquents who had spent the better part of their lives in the slums of Buenos Aires and who had performed as dancers and musicians—the so-called Murgueros— during the Argentinean carnival (Murga).

The performance, with a title that refers to the different ways in which a steak can be cooked (rare, medium, well-done), immediately created an electric atmosphere that oscillated between the carnivalesque, aggressive tumult, and more intimate moments of biographical narration by the youths. Already in the opening scene, the presence of fifteen Murgueros laughing and bawling as they occupied the stage with whistles and drums, transformed the performance venue, the medieval Cloître des Carmes, into a space bursting with bodily energy: Two performers careered onto the stage in bumper cars while others started to chase around, knocking one

Figure 11.2 Cruda, vuelta y vuelta, al punto, chamuscada by Rodrigo Garcia, © christianberthelot.com.

another to the ground and spraying each other with beer. A foosball table was carried on, a young man in a fur coat started to rap, another danced to his tune, his sweeping gestures dangerously close to the heads of the frontrow spectators. As is traditional in a Murga, the performers in later scenes threw flour, paint, and tomato sauce or squirted foam all over each other and, in the end, cleaned themselves with a high-pressure water spray. These scenes of tumult were set in contrast to Garcia's texts, read out by the actor Juan Loriente and displayed on a screen in the background, as well as to the quieter scenes, in which the youths recounted episodes of their lives. Garcia, who, like the performers, had spent his childhood in the slums of Buenos Aires and, as an adolescent, had also taken part in the Murgas—banned during the military dictatorship—had statements projected on to the wall: “The new life of the residents who inhabit this new world has started in delirium” or “Given the fiasco of the democratic system as the ideal of our shared lives, something must be discovered to take its place.”22

What kind of political theatre were the spectators confronted with here? The youth on stage were not calling out for class war, and the theatre did not present itself simply as a “space of encounter.” A latent aggression was palpable even in the intimate scenes during which the protagonists reported on street violence and family life. Any sense of compassion or empathy the public may have felt was countered by a perceptible dissociation, which came to the fore during the chaotic and carnivalesque moments of playful or violent excess. In spite of their frequently harrowing biographical tales, the performers did not appear as victims. Rather, they took to the stage as autonomous agents, almost as though they themselves were the perpetrators, appropriating the theatrical space in a manner specific to them and unsettling the spectators in the process. The performance became a party; the theatre was declared a festival. And the performance space did not remove the boundary between stage and audience, but instead separated them atmospherically, despite the very real incursions and numerous transgressions. The protagonists were viewed by the audience as foreign and uncontrollable; they seemed not to belong there, in this space of art, but rather to occupy the space in order to turn it into their own. Thus, they tore down the boundaries between the theatre and their everyday social lives, while, in the very act of reenactment, simultaneously transforming their daily lives, their celebratory ways, and their actions into artistic performance material. The expressed utopia of discovering a “new world” in the “delirium” was thereby reflected in the heterotopian carnivalesque space of the performance.

Some may argue that these or similar events on stage in fact depict nothing other than a modern ethnological exposition of raving street kids, or even a variant of what was witnessed in England's cities in 2011 or in the suburbs of Paris in 2005. According to the German sociologist Heinz Bude, the main problem of social exclusion is that certain socioeconomically marginalized and sociospatially isolated groups are identified in public only as sporadically formed mobs.23 Do performances such as these merely serve to strengthen the negative perception of the socially disadvantaged as “mobs”? And were not the youths' speeches simply understood as “noise,” as Jacques Rancière describes the disagreement of the sans-part, which is responsible for producing politics as dissent in the first place?24

Considered from the perspective of the millionaires, cited or referred to in Volker Lösch's production, who battled against the perceived reality of the performance, the response to these two questions must, in some respect, be positive. Nonetheless, as previously noted, it is important to remember that the theatre not only represents a social public space but also is an externally located heterotopia that can function according to other conditions and rules. The violence and aggression on stage in Avignon was capable of shocking, because, up to a certain point, it appeared as social reality. For the spectators, however, the irritating and, at the same time, fascinating moment lay in the very fact that this game, which oscillated between excessive celebration, violence, and aggression, and from which the performers visibly took great pleasure, had no bearing on the reality of their everyday lives, but concerned the theatre alone, taking place somewhere on the threshold between art and social life. The politics of art, as Rancière explains, consists precisely in its promise of emancipation as a separate reality and of the related “indifference” called upon to constitute a region of “free play.”25 Paradoxically, this promise nevertheless aims at revoking the status of art as a separate reality

Figure 11.3 Cruda, vuelta y vuelta, al punto, chamuscada by Rodrigo Garcia, © christianberthelot.com.

and at transforming it into a form of life.26 Carnival and theatre enable this type of game, for they take possession of a space and a time. In this emancipatory sense, the politics of carnival and the politics of art are necessarily the antithesis of day-to-day politics. The politics of art is at once a played-out state of exception and, during the game, an emancipatory promise. But one must not forget that, unlike art objects, theatrical performance (and also the carnival) cannot refer to or seek support in a claim to autonomy, still less its sovereignty. Whether on the stage or in the streets of Buenos Aires, the game is necessarily embodied and, as a real social situation, is always unpredictable or risky. Even in the “aesthetic regime,”27 performances and theatre productions can change into a politics of social reality. There is simply no guarantee of “impact reduction” in a performance.

Viewed as such, the game played by the Murgueros also takes on the appearance of an unstable order between fiction and reality, and between a politics of art and a politics of social reality, which, through the representation of others and the expressed utopia, simultaneously releases a moment of otherness. Rodrigo Garcia does not offer the audience a fail-safe access to theatre as a heterotopia of deviance, which could fall back on exoticism or an exploitation of others. Rather, what comes to light in the youths' irrepressible performance, as they occupy and appropriate the space in an emancipatory fashion, is that uncontrollable element of the other, which, as phenomenologist Bernhard Waldenfels puts it, “by moving both within and outside of the established order, makes its unheard [and unheard-of] claims audible.”28

1. The 2008 rich list quoted here is based on my recollections and notes from the performance I attended, the list of the three hundred richest Germans as published in the October 2008 special edition of Manager Magazin, and an e-mail exchange with the dramaturge Beate Seidel. Because the scene was cut for legal reasons from the video recording I received, and because the script is regularly adapted according to the new lawyers' letters, the wording quoted here may differ from that of more recent performances.

2. Peter Kümmel, “Umsturz auf Probe. Auf geht's! Revolution! Führt die Finanzkrise zum Klassenkampf? Am Hamburger Schauspielhaus fordern die Armen schon mal die Superreichen heraus,” Die Zeit 45 (October 30, 2008).

3. Cf. Augusto Boal, Theatre of the Oppressed, trans. Charles McBride and Maria-Odilia Leal McBride (London: Pluto Press, 1979).

4. Andreas Kotte, Theaterwissenschaft. Eine Einführung (Köln: Böhlau Verlag, 2005), 41–44.

5. Michel Foucault, “Different Spaces,” in James D. Faubion (ed.), The Essential Works of Foucault, vol. 2: Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology (New York: The New Press, 1998), 175–185, 178.

6. Ibid., 181.

7. For a comprehensive account of the relationship between theatre and festival in ancient Greece, cf. Peter Wilson (ed.), The Greek Theatre and Festivals: Documentary Studies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

8. Cf. Matthias Warstat, “Fest,” in Metzler-Lexikon Theatertheorie, ed. Erika Fischer-Lichte, Doris Kolesch and Matthias Warstat (Stuttgart: Metzler, 2005), 101–104.

9. Concerning Richard Wagner and Max Reinhardt, see Erika Fischer-Lichte's contribution to this volume.

10. Hans-Thies Lehmann, Postdramatic Theatre, trans. Karen Jürs-Munby (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2005), 155.

11. Ibid.

12. Foucault, “Different Spaces,” 179.

13. Victor Turner, “Variations on a Theme of Liminality,” in Sally F. Moore and Barbara C. Myerhoff (eds.), Secular Rites (Assen: Van Gorcum, 1977), 36–57, 40.

14. Cf. Victor Turner, The Ritual Process, Structure and Anti-Structure (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1969), 95.

15. Cf. Erika Fischer-Lichte, The Transformative Power of Performance: A New Aesthetics (London: Routledge, 2004), 174–180.

16. Alain Badiou, “Theses on Theatre,” in Handbook of Inaesthetics, trans. Alberto Toscano (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005), 72–77, 74.

17. Voetzoeker [Squib] program on the Belgian television channel Canvas on May 27, 2004, available on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a3PrVFMH_Po (accessed August 31, 2012).

18. In his contribution to this volume, for example, Ludger Schwarte points to the not negligible fact that many amphitheatres contained more seats than there were citizens in the city, and not an equal number of both, as suggested by Sellars.

19. Cf. Axel Honneth, “Recognition: Invisibility: On the Epistemology of ‘Recognition,’” Aristotelean Society Supplementary 75 (2001), 111–126; Jacques Rancière, Disagreement. Politics und Philosophy (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999).

20. Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998), 28–29.

21. Gerhard Lenski, Power and Privilege (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1984), 281–284.

22. The phrases projected on to the wall were in French, but they were spoken in Spanish by the actor Juan Loriente.

23. Heinz Bude, “Das Phänomen der Exklusion. Der Widerstreit zwischen gesellschaftlicher Erfahrung und soziologischer Rekonstruktion,” in Heinz Bude and Andreas Willisch (eds.), Exklusion: Die Debatte über die Überflüssigen (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2007), 246–260, 247.

24. Rancière, Disagreement, 10.

25. Cf. Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, trans. Gabriel Rockhill (London: Continuum, 2004), 26f. Rancière of course refers here to Schiller's Spieltrieb.

26. Jacques Rancière, Aesthetic and Its Discontents, trans. Steve Corcoran (Cambridge, MA: Polity Press, 2009), 36.

27. Rancière describes the “aesthetic regime” as an ontological mode of art that originated in a historical promise of equality and autonomy (principally in the nineteenth century), and a self-identification of art that no longer concerns representation but can elevate everything to art and thus expresses an emancipatory promise of equality by turning life into art.

28. Bernhard Waidenfels, Der Stachel des Fremden (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1990), 7.

Agamben, Giorgio, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, trans. Daniel Heller-Roazen, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998.

Badiou, Alain, “Theses on Theatre,” in Handbook of Inaesthetics, trans. Alberto Toscano, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005, 72–77.

Boal, Augusto, Theatre of the Oppressed, trans. Charles McBride and Maria-Odilia Leal McBride, London: Pluto Press, 1979.

Bude, Heinz, “Das Phänomen der Exklusion. Der Widerstreit zwischen gesellschaftlicher Erfahrung und soziologischer Rekonstruktion,” in Heinz Bude and Andreas Willisch (eds.), Exklusion: Die Debatte über die Überflüssigen, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2007, 246–260.

Fischer-Lichte, Erika, The Transformative Power of Performance: A New Aesthetics, London: Routledge, 2004.

Foucault, Michel, “Different Spaces,” in James D. Faubion (ed.), The Essential Works of Foucault, vol. 2: Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology, New York: The New Press, 1998, 175–185.

Honneth, Axel, “Recognition: Invisibility: On the Epistemology of ‘Recognition,’” Aristotelean Society Supplementary, 75, 2001, 111–126.

Kotte, Andreas, Theaterwissenschaft. Eine Einführung, Köln: Böhlau Verlag, 2005.

Kümmel, Peter, “Umsturz auf Probe. Auf geht's! Revolution! Führt die Finanzkrise zum Klassenkampf? Am Hamburger Schauspielhaus fordern die Armen schon mal die Superreichen heraus,” Die Zeit, 45, October 30, 2008.

Lehmann, Hans-Thies, Postdramatic Theatre, trans. Karen Jürs-Munby, Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2005.

Lenski, Gerhard, Power and Privilege, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1984.

Rancière, Jacques, Aesthetic and its Discontents, trans. Steve Corcoran, Cambridge, MA: Polity Press, 2009.

Rancière, Jacques, Disagreement. Politics und Philosophy, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

Rancière, Jacques, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, trans. Gabriel Rockhill, London: Continuum, 2004.

Turner, Victor, The Ritual Process, Structure and Anti-Structure, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1969.

Turner, Victor, “Variations on a Theme of Liminality,” in Sally F. Moore and Barbara C. Myerhoff (eds.), Secular Rites, Assen, Netherlands: Van Gorcum, 1977, 36–57.

Waidenfels, Bernhard, Der Stachel des Fremden, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1990.

Warstat, Matthias, “Fest,” in Erika Fischer-Lichte, Doris Kolesch, and Matthias Warstat (eds.), Metzler-Lexikon Theatertheorie, Stuttgart: Metzler, 2005, 101–104.

Wilson, Peter (ed.), The Greek Theatre and Festivals: Documentary Studies, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a3PrVFMH_Po (accessed May 22, 2012).