Figure 13.1 Circus Schumann around 1900, courtesy of the Institute for Theatre Studies, Freie Universität Berlin.

Erika Fischer-Lichte

Translation by Michael Breslin

and Saskya Iris Jain

In the 1960s, Western theatre began to move out of the established and representative buildings in which it had been hosted. With this practice, which has continued until today, theatre set about appropriating a variety of spaces that had been neither conceived nor built for performances, including empty factories, disused mines, former tram depots, abattoirs, department stores, underground parking garages, roads, public squares and parks, as well as ateliers, apartments, garages, and cellars. It has become almost impossible to fi nd a space that has not, at one time or another, been considered suitable for performances.

This development was rooted, among other things, in a general critique of the theatre as a bourgeois institution. It was a reaction to the insularity of the theatre, and to the perceived distance between it and the daily life and work routines of the majority of the population, and against the impenetrable borders laid down by the strict division of the theatrical space into one area for actors and another for spectators. Therefore, the policies that underpinned theatre's appropriation of new spaces attempted to shift the threshold between the theatre and other domains of everyday life, create shared communities between actors and spectators, and institute a participatory form of democratic activity. Abandoning existing theatre buildings in this manner may appear revolutionary against the backdrop of the postwar period and the 1950s, particularly in the Federal Republic of Germany, where the many theatre buildings destroyed during the war were rapidly reconstructed or replaced. But such an interpretation fails to recall that, in appropriating new spaces, the theatre was merely reverting to policies introduced during the late nineteenth century and that had since become a recurrent feature of certain bursts of modernization in the theatre of the Western world. Indeed, the appropriation of new spaces was a typical response to the crises generated by the modernization of society and theatre. This chapter analyzes policies of spatial appropriation developed at the turn of the twentieth century (ca. 1870–1919) with reference to three examples that exhibit signifi cant defi n-ing characteristics and that have the potential to serve as a model: Richard Wagner's plans for a temporary theatre on the banks of the Rhine, the English and American Pageant movement (1905–1917), and Max Rein-hardt's appropriation of new spaces.

In his early theoretical works Art and Revolution (1849), The Art-Work of the Future (1849), and Opera and Drama (1850/1851), Wagner combined thoughts on aesthetics and the philosophy of history to justify theatre's departure from established buildings. His conception, similar to that of Schiller, the German Idealists, and Karl Marx, was determined by an understanding of history as a three-stage process. Wagner believed that the Greek polis represented the ideal historical state, for in it each person could develop fully as an individual and as a species-being (Gattungswesen). “The public art of the Greeks,” he concluded, “which reached its zenith in their tragedy, was the expression of the deepest and noblest principles of the people's consciousness.”1 A trip to the theatre, therefore, was also a public matter of great importance:

This people, streaming in its thousands from the state-assembly, from the Agora, from land, from sea, from camps, from distant parts—filled with its thirty thousand heads the amphitheatre. To see the most pregnant of all tragedies, the Prometheus, came they; in this Titanic masterpiece to see the image of themselves, to read the riddle of their own actions, to fuse their own being and their own communion with that of their god; and thus in noblest, stillest peace to live again the life which a brief space of time before, they had lived in restless activity and accentuated individuality. ⋯ For in the tragedy he found himself again—nay, found the noblest part of his own nature united with the noblest characteristics of the whole nation.2

Greek tragedy was not only the “perfect Art-work,” but also the representation of “a free and lovely public life” and thus an utterance of both the individual and public conscience.3 Greek tragedy, “the great unitarian Art-work of Greece,” marked the realization of a political, social, anthropological, and aesthetic ideal.4 Yet this ideal necessarily faded away with the dissolution of the Athenian polity, as the individual and the state fell apart. Nationalization had taken hold and was steadily growing, while the increasing privatization, specialization, and division of labor that marked the individual sphere transformed man into “a mere instrument to an end which lay outside himself.”5 The “whole man” had become torn apart into the man of body, the man of heart, and the man of understanding.6 Each of the arts now took “its own way, and in lonely self-suf ciency” pursued its own development.7 Thus, the individual arts “developed to the highest of their capabilities,” reaching a point from which further progress was unimaginable: “Nowadays, there is nothing left for each of the individual arts to discover. This is true of the visual arts, as it is of dance, music and poetry.”8 They had become sterile.

For Wagner, this twin evolution of the state and the individual marked the contemporary phase of the history of mankind; the two stood in opposition to one another, their dif erences irreconcilable. Individuals, specialized as never before, had become tools to an end rather than ends in themselves, and the essence of “Art, as it now fi lls the entire civilized world,” had become an industry.9

Wagner's assessment of his period was damning. The restoration of man in his entirety—that is, uniting the man of body, the man of heart and the man of understanding, and reconciling the interests of the individual and the state—together with the restoration of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total art-work) along its evolutionary path seemed quite impossible. Only two options, Wagner thought, could bring about a radical shift in relations: a “Revolution” or a “revolutionary” art.10 Whereas the Revolution would achieve its objective in conjunction with certain political and social factors, revolutionary art would proceed from the reunifi cation of the individual arts. The fi nal outcome would, however, be a concordance of the two.

On November 12, 1851, Wagner wrote to his friend Theodor Uhlig in Dresden:

A performance is something I can conceive of only after the Revolution; only the Revolution can of er me the artists and listeners I need. The coming Revolution must necessarily put an end to this whole theatre business of ours: they must all perish, and will certainly do so, it is inevitable. Out of the ruins I shall summon together what I need: I shall then fi nd what I require. I shall then set up a theatre on the Rhine and send out invitations to a great dramatic festival. After a year's preparation I shall perform my entire work within the space of four days: with it I shall make clear to the people of the Revolution the meaning of that Revolution, in its noblest sense. That audience will understand me; the present one cannot.11

Nonetheless, that same year, Wagner drafted A Theatre in Zurich (1851), a reform paper outlining what he believed to be the requisite preconditions for a fundamental reform of the theatre in the Swiss city, but within the framework of existing social conditions. Over the course of the following two decades, he would write a series of similar reform papers, always adjusted to local conditions and which therefore dif ered on certain points. To one underlying part of his argumentation, however, he remained forever committed: There must be no compromise in the struggle against the prevalent bourgeois perception of the theatre as an “industrial institution,” and of the performance as a reproducible commodity, which the paying public could regulate upon demand, as it might a product of industry.

From his critique of the industrial character of performances, Wagner deduced a number of important and necessary organizational changes. First among these was the transformation of the theatre into a festival, substituting the singularity of an event for its arbitrary reproducibility. To celebrate this festival, people would be drawn away from the cities to assemble at a precise location, perhaps along the banks of the Rhine or in a “temporary theatre.” The latter, an expression on which Wagner would insist his entire life, should be “as simple as possible, perhaps merely of wood, its sole criterion being the artistic suitability of its inner parts.”12 The festival's participants would be welcomed as guests, not as paying customers. Only under these conditions could the festival community realize the utopia of a “free and lovely public life.”

The theatre was therefore called upon to shift the boundaries between it and other life-world domains. Its appropriation of the meadows that lined the Rhine was to be both aesthetic and political, for this freely accessible space would be turned into a “fairground” (Festwiese), and the individuals present transformed into members of the new festival community.

This plan, however, never came to fruition. There were no invitations to a festival on the banks of the Rhine, where Wagner's temporary festival house never saw the light of day. In fact, the fi rst festival took place on the “Green Hill” of Bayreuth in 1876. And, as was the case with every other operatic performance, the public had to pay to attend. Yet the inside of the “temporary theatre” had indeed been conceived to host a “democratic festival.” Almost two thousand seats were arranged according to the design of an ancient amphitheatre, gradually rising in an arc from the proscenium to the back wall. It was in this space that the new aesthetic of the Gesa-mtkunstwerk would “wrap [the spectators] in a suggestive delusion, in a prophetic dream of things never before experienced.”13

The true ef ect exerted by the staging of the Ring during this first Bay-reuth Festival is described by the composer Peter Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) in his recollections of 1876:

I should say that anyone who believes in art as a civilizing force ⋯ must experience a most agreeable feeling in Bayreuth at the sight of this tremendous artistic enterprise which ⋯ , by virtue of its vast dimensions and the degree of interest it has awakened, acquired epoch-making signifi cance in the history of art. ⋯ As to whether Wagner is right to go so far in the service of his idea, or whether he has overstepped the limits defi ning the balance of aesthetic factors which ensure that a work of art is durable and lasting; whether or not art will now take Wagner's achievement as its starting-point and proceed along the same path, or whether the Nibelungen Ring marks in fact a point of infl exion after which only a reaction in the opposite direction is possible—those are as yet open questions. What is, however, certain at any rate is that something has taken place in Bayreuth which will occupy the thoughts even of our grandchildren and great-grandchildren.14

The reaction, which Tchaikovsky had feared and warned against in 1876, surfaced not long afterward, on the occasion of the second Bayreuth Festival in 1882, at which only Wagner's Parsifal was performed. Wagner had resisted the temptation, particularly strong during the Franco-German war and the formative period of the German Reich, of allowing his festivals to serve chauvinistic and nationalist purposes. But he had also said to his wife Cosima on December 12, 1870, that he needed “an Emperor ⋯ for the art-work of the future.”15 However, as the fi rst stone of the theatre's foundations was laid in May 1872, Wagner rejected suggestions linking it to a national history. Certainly, he would have wished “to found a theatre for the Germans”; but he was adamant that his was not a “national theatre.” “I am not,” he argued, “entitled to establish such a connection. For where is the ‘nation’ that might erect such a theatre?”16 Yet Wagner's very starting point, the “Revolution” on which he had placed so much hope, had never seemed so distant. It was a dilemma from which Wagner extricated himself by likening his Festspielhaus to a “temple.” This maneuver uncoupled aesthetic concerns from the philosophy of history and from politics, and suggestively raised art to the level of a religion. This new orientation, which would later become more explicit, was the one adopted by Parsifal. Whereas the staging of the Ring was openly conceived as a model on which future performances, on the stages of “normal” theatres, would be based, Wagner conceded from the outset that Parsifal was destined for Bayreuth alone:

In fact, how can an action, into which the most sublime mysteries of the Christian faith are introduced, be presented in theatres like ours? ⋯ Imbued by this spirit, I called my “Parsifal” a Bühnenweihspiel, a “Festival Play for the Consecration of the Stage.” I must therefore endeavor to consecrate a stage to this work, and this can only be my isolated stage Festival House in Bayreuth. There the “Parsifal” is to be given for all time, and there only; never is the “Parsifal” to be presented in any other theatre, nor of ered any audience as a mere diversion.17

The redefinition of the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, now home to a religion of art, which had discreetly raised its head in his speech marking the start of the building work, was now complete, defi nitively transforming the great democratic festival into a religious service. Bayreuth had become a place of pilgrimage, to which young people and disciples of Richard Wagner's art would fl ock expectantly.

A temple occupied the very place where previously a democratic festival house had been planned. The movement away from city theatres and the appropriation of new spaces far from large cities targeted, to begin with, the politicization of art as a path to radical democratization. Wagner believed these to be promising strategies to rid art of its industrial characteristics, create spaces in which a “free and lovely public life” might unfold, and encourage art and life to form a new, close-knit relationship. Of these objectives, only one, the festival house auditorium, built for a democratic festival, survived until the first Bayreuth Festival. However, only those with the requisite purchasing power were allowed to enter it. Wagner had believed the modernization of the theatre would come about through the institution of a participatory democracy allowing all “sons of Germania,” irrespective of status or wealth, to take part in productions of his music dramas. He failed in this ambition. Instead, with the first staging of Parsifal, art had been transformed into something sacred, and even the religion of art's most fervent disciples had to pay the required fee to enter the space devoted to it, that is, the “holy precinct” of the “temple.”

The pageant movement emerged in England at the beginning of the twentieth century as a response to the crises produced by the radical modernization of society. The profoundly anti-modernist conceptions upon which it was founded cannot be overlooked.

Pageants were conceived and intended as a bulwark against the negative consequences of industrialization and urbanization, namely the loss of solidarity, the disintegration of society, the lack of bonds, and “disorder.” As expressed by Louis Napoleon Parker, the initiator of Pageantry, a “properly conducted pageant [should be designed] to kill the modernizing spirit.”18 The root cause of the modern crisis had been diagnosed by Émile Durkheim more than ten years earlier. In a society characterized by the division of labor, the dif culty, according to the French sociologist, lay in establishing something akin to a moral bond between competing individuals.19 The promotion of individualism transformed “the individual [into] a sort of religion,” while industrialization and urbanization led to the development of an increasingly anonymous mass within cities.20 As the opposition between individuals (who nurtured a type of cult of personality) and the masses became gradually more pronounced, society threatened to fall to pieces.

The pageant movement reacted to this precarious situation. It appealed to the history of a city, village, or hamlet in an attempt to forge a community among its inhabitants, who were to be brought together by a collective local identity. It is interesting to note that in his autobiography, Parker cites Wagner's Bayreuth Festival and the tradition of Bavarian popular plays as his most important sources of inspiration. Parker's first pageant, The Pageant of Sherbourne (1905), which celebrated the 1200th anniversary of the city, set the pattern for those that followed. They took place in open, outdoor spaces, always close to historical monuments, and required the participation of large numbers of amateur actors and local artists (writers, composers, musicians, architects, painters, etc.). In structure, they were not unlike religious dramas, but the hero of the performance was the town itself rather than a saint or another similarly signifi cant character. A pageant consisted of a series of historical episodes, joined together by a prologue and an epilogue, and accompanied by narrative and dramatic choruses, musical interludes, and long parades. Typically, it began with the town's Roman period, and ended with the Civil War; the besieged population's uprising against their Cromwellian usurpers marked its apotheosis. Parker decreed that any period or event after the mid-seventeenth century could not be portrayed: the modern era, with its class struggles, political divisions, and confrontations, was not appropriate. The social objective of a pageant, Parker claimed, was as a “festival of brotherhood in which all distinctions of whatever kind were sunk in common ef ort,” one that might “reawaken civic pride [and] self respect.”21 Furthermore, he insisted on the religious nature of the pageant, which, he asserted, “is a part of the great Festival of Thanksgiving to Almighty God for the past glory of a city and for its present prosperity.”22 Without exception, his pageants started and ended with a service of remembrance.

Two characteristics are particularly representative of pageants. The first of these is their “communitarian ethos.”23 Pageants were popular because they appropriated a space that was central to the city's history, and in doing so enabled, or rather demanded, the participation of thousands of people, either to assist in the preparation of the event, and/or as performers and spectators. Pageants were regarded as a theatre of the people, created by the people, for the people—one that enabled a communal and quasi religious experience. The second characteristic concerned the pageant's claim to authenticity:

Scenes in a Pageant convey a thrill no stage can provide when they are represented on the very ground where they took place in real life; especially when they are played, as often happens, by descendants of the historical protagonists, speaking a verbatim reproduction of the actual words used by them.24

The authenticity of the space sought to refl ect and guarantee historical continuity. A pageant's most important task was thus to appropriate such space using strategies that constantly referred to this authenticity. A typical pageant depicted hundreds of years of English history in such a way as to give the impression that things had essentially remained the same. It dissolved linear time “into the seductive continuity of national tradition” and blurred the boundaries between theatre and politics, as well as between theatre and religion.25

Pageants were therefore expected to help society overcome the crises triggered by modernization. They did so by generating a backward-looking utopian vision. But this vision was in itself contradictory. From the very beginning, pageants combined a faith in progress with distinctive anti-modernist traits; they pledged creative innovation but enacted traditional civil and religious rituals. Pageants proclaimed the advent of a form of participatory democracy, in which all individuals could take part on an equal footing. But, simultaneously, they of ered reassurances that, even in times of upheaval and change, history would continue to run its comforting course and that it alone could serve to strengthen and stabilize the community's collective identity. A community, so the argument went, existed through and thanks to its history. Pageants held up each of their participants as artists capable of artistic invention and, at the same time, opened the way to a locally bound communal experience. The respective needs of the individual and the community appeared beautifully reconciled, leading the participants to believe that they could use the pageants to overcome the crisis, that is, to heal the “sicknesses” caused by industrialization.

This contradiction remained one of its defi ning features when, in 1908, the pageant movement was introduced to the United States on the occasion of the 250th anniversary of the city of Philadelphia. However, the faith in progress that marked this so-called Progressive Era overtook the movement's anti-modernist tendencies. Pageants were now founded on the belief “that history could be made into a dramatic public ritual through which the residents of a town, by acting out the right version of their past, could bring about some kind of future social and political transformation.”26 Just as in a rite of passage, the focus came to rest on the pageant's transformative potential for individuals and places: The history of a specifi c location was at once enacted and appropriated by those living there, allowing them (and above all, the immigrants) to take control of their own future.

Percy MacKaye, one of the most infl uential supporters of the pageant movement, characterized this transformation as “the conscious awakening of a people to self-government.”27 Based on the same premise, the historian David Glassberg described historical pageants as “a public ritual of communal self-discovery” that would ultimately lead to “the integration of the town's various peoples and point to the reforms necessary for their continued future progress.”28 English pageantry tended to glorify the past in a bid to provide inhabitants with the opportunity to appropriate the city space as their own. In contrast, American historical pageants were composed of a peculiar amalgamation of early forms of historical representation, such as public processions, tableaux vivants, or reenactments in historical costume, on the one hand, and new elements, such as modern dance, the reenactment of scenes from social, domestic, or political life, and a popular festival-style grand fi nale, on the other. All of these forms can be interpreted as specifi c strategies of spatial appropriation. Their content covers “the theme of community development, the importance of townspeople keeping pace with modernity while retaining a particular version of their traditions, [and] the rite-of-passage format signifying the town in graceful transition.”29 Advocates of the pageant movement were convinced that direct involvement in such expressive and playful forms of social interaction would create an emotional bond between participants, thus tearing down the social and cultural barriers that divided inhabitants and, in particular, integrating immigrants. In this manner, the latter were to become familiar with the history of their city or nation, generating a new sense of belonging between citizens and encouraging a more enduring and shared engagement in civil society. Pageants, it was believed, would have a positive ef ect on a society described by Percy MacKaye in 1914 as “a formless void,” that is, a hodgepodge of dif erent immigrants, social classes, and interest groups. From these disparate sources, a coherent public would emerge, one structured around a cohesive history, itself based upon the array of recent social and technological changes to have beset a specifi c location.30 Nevertheless, the confl icts that accompanied these changes, and, more specifi cally, the resistance with which an expanding industrial capitalism was met, were simply omitted in the pageants' historical account of progress's relentless surge—as was any mention of the struggles of African Americans or the trade unions. Undeterred, some of the latter groups appropriated the new genre for themselves and adapted it to their specifi c needs. A spectacular example was the Paterson Strike Pageant, performed in 1913 in New York's Madison Square Garden by the striking workers and supporting artists.31

Historical pageants were quickly overtaken after World War I by the latest trends in popular culture. They were no longer a suitable medium for the social, aesthetic, and moral renewal of a city, nor were they capable of conveying a corresponding sense of community. By 1917, the optimism surrounding the Progressive Era had dissipated, replaced with precisely the type of violent dissent that the pageants had tried to appease or, at the very least, conceal. Nonetheless, pageants can be regarded as the first of the mass spectacles later practiced across the Western world in the period separating the world wars.

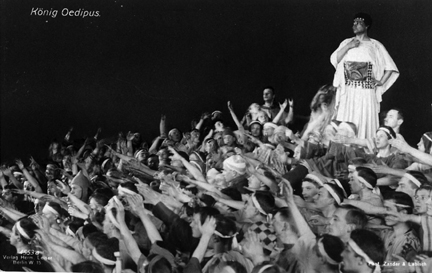

From the beginning of his career onward, the director Max Reinhardt conceived and implemented specifi c strategies for the appropriation of performance spaces. “Ever since I started to work in the theatre,” he would say, “I have been pursued, and ultimately guided, by one particular thought: bringing together the actors and spectators as close to one another as is physically possible.”32 To achieve this objective, and to put it to the test, he set about the construction or renovation of more than twenty theatres: tiny and convivial theatres, intimate theatres, mass theatres in large-scale halls, arena stages, and space stages. These converted or newly constructed buildings could not satisfy Reinhardt for long, however, and it became an insatiable fantasy of his to discover, and then appropriate, new spaces for his productions. He came upon these in exhibition and festival halls, in circuses and marketplaces, in churches, gardens and parks, or in squares and streets throughout the city. In the summer of 1910, Reinhardt produced Sophocles's King Oedipus at the Munich Musik-Festhalle, which he had converted into an arena.

A few months later, the production was moved to Berlin's Circus Schumann, before being shown in the circus rings of the biggest cities across Europe and America. It was also in the Circus Schumann that, in 1911, he

Figure 13.1 Circus Schumann around 1900, courtesy of the Institute for Theatre Studies, Freie Universität Berlin.

directed Aeschylus's Oresteia and Hugo von Hofmannsthal's Everyman (Fig. 13.1). The same year, his set designer Ernst Stern converted London's Olym-pia Hall into a spired Gothic cathedral, where spectators and actors were united for the staging of Vollmoeller's The Miracle. To mark the opening of the Salzburg Festival in 1920, Reinhardt produced Everyman on a board platform in front of the Salzburg Cathedral, and, in 1922, Hofmannsthal's Great World Theatre of Salzburg at Salzburg's Collegiate Church.

Reinhardt first produced A Midsummer Night's Dream in 1905, making spectacular use of the newly installed revolving stage. In the years that followed, however, he transferred Shakespeare's play into real woods, parks, and gardens: in 1910 in the pine forest of Berlin-Nikolassee and the same year in the Seidl Park in Murnau (Germany), where amid hills, birches, and ponds, he went some way toward creating a “Theatre-Environment.” He produced the same play at the Boboli Gardens in Florence in May 1933 and, a few months later, on Headington Heath near Oxford. In 1934, he took the Merchant of Venice to its “original setting” with the staging at the Campo di San Trovaso in Venice.

If policies of spatial appropriation are viewed as strategies for the modernization of theatre (and/or society), then Reinhardt's productions of Greek tragedies in the Circus Schumann are undoubtedly of greatest interest. With King Oedipus and the Oresteia, Max Reinhardt ef ectively put into practice his idea for a new people's theatre, the so-called Theatre of the Five Thousand. This theatre sought to attract “large sections of the population as visitors, the very people who today, for economic reasons, are unable to attend.” Reinhardt declared that “if thousands upon thousands were to unlock the sealed doors, theatre would again become a social factor in this day and age.”33

In many respects, this new people's theatre constituted a break with the principles of the Bildungstheater and the illusionistic theatre of the bourgeoisie. This was quite visibly the case with regard to both the space in which the performance took place and the social makeup of the public. The Circus Schumann traditionally hosted crowds more acquainted with the teasing and nerve-racking spectacles of acrobats and animal tamers. The theatre thus appropriated this space of the spectacle for itself but simultaneously of ered the masses the types of plays with which only the educated bourgeoisie had hitherto identifi ed. One objective was evidently to remove the opposition between these dif erent social classes. Yet Reinhardt also sought to overcome the barriers that separated the actors and the spectators: For in this space, the actors in the circus ring were no longer positioned immediately opposite the spectators but were surrounded by them.

In the Berliner Tageblatt (November 8, 1910), Fritz Engel commented as follows on the composition of the public during King Oedipus:

This circus holds fi ve thousand spectators. Five thousand who stream towards it. ⋯ The school children sit in the top row, impatient and gleeful. Further down, members of the trade unions, and, in the boxes and front rows, the most elegant folk from the west of the city. ⋯ Next to these, men from all walks of life, scholars, who usually shun the theatre, and members of parliament, who usually have other business to go about. The court boxes are also full: our Prince August Wil-helm and his brother Oskar turned up accompanied.34

It seemed that the establishment of a new people's theatre was imminent. Reinhardt's theatre suggested that it was possible to mix people from difer-ent social strata, classes, milieus, groups, and backgrounds. It also altered the spatial boundaries and therefore introduced a new relationship between actors and spectators. The overall ef ect was the constitution of new communities, and it is not inconceivable that these productions were the true realization of Wagner's idea for a democratic festival.

In the productions of both King Oedipus (stage by Franz Geiger, costumes by Ernst Stern) and the Oresteia (stage and costumes by Alfred Roller), the circus ring was bordered by a palace building; it was located where the acrobats' entrance was usually found and had broad steps leading up to it. The circus ring remained free. A rust colored velum was stretched out above the ring and the spectators, just beneath the roof of the tent. The beginning of King Oedipus exhibited the three characteristic practices that Reinhardt used to establish a break with the illusionistic theatre of the bourgeoisie:

Long drawn-out fanfares. Blue light falls in the ring that has become the orchestra: bell-like sounds clang, swell, voices moan, becoming louder, surging, and the people of Thebes swarm in through the central entrance opposite the built-up stage. Running, stampeding, with raised arms, calling, wailing; the space is fi lled with hundreds of them and their bare arms stretch to the sky.35

The practices employed here are (1) the occupation and control of the space by the masses, (2) the creation and ef ect of atmospheres, and (3) the deployment of dynamic and energetic bodies.

(1) The chorus was composed not of fi fteen but of hundreds of members. Not only did it move in the arena, which it seemed to partially inundate, it also occupied part of the space that appeared reserved for the spectators, operating among them. In the Vossische Zeitung on October 4, 1911, the critic Alfred Klar described the deployment of the chorus:

the distribution of the acting onto the space in front of, beneath, behind, and among us; the never-ending demand to shift our points of view; the actors fl ooding into the auditorium with their fl uttering costumes, wigs, and make-up, jostling against our bodies; the dialogues held across great distances; the sudden shouts from all corners of the theatre, which startle and misguide us—all this is confusing: It does not reinforce the illusion but destroys it.36

The critic was obviously ill at ease. This was due to the new perceptual demands made of him, as well as the requirement to alter the position of his body to be able to see everything. His discomfort was also caused by the way in which the masses occupied the space, pressing up against the spectators' bodies; they seemed no longer to respect the physical boundaries between individuals. But the tremendous success of the production suggests that the critic's discomfort was in stark contrast to the delight felt by most of the spectators. By confronting the “masses” in the auditorium and the “masses” in the orchestra, and by dissolving the boundary between the actors and spectators, Reinhardt created the conditions for the establishment of a shared community between the two groups, of the type the avant-garde movement had been calling for since the turn of the century. But the community thus formed was of a specifi c nature. It was not based on common convictions, beliefs, ideologies, or, as in the pageants, a common history. Rather, it formed around and during a shared experience of the performance. Accordingly, it could not outlast the performance itself, and the two came to an end at the same time. This ephemeral community was therefore unable to permanently redefi ne the relationship between members of otherwise contrasting social milieus.

(2) The ef ect of atmosphere also contributed to the establishment of this fl eeting, theatrical community. The various reviews indicate that this can be attributed specifi cally to the constantly changing light (blue, violet, green, grey, red-brown, bright sunlight, etc.), and the orchestration and varying rhythms of movement, music, and sounds. All the reviews refer to the dif erent “moods” created by the production and thus bear witness to how powerful the atmospheres were—although these were not always viewed positively.37 Paul Goldmann (Neue Freie Presse, November 1920), for example, lamented that Reinhardt did not use voices

to create an intellectual ef ect, but rather to create acoustic waves which are a signifi cant part of the modern register of atmosphere. The chorus thus, must produce all kinds of sounds imaginable: muttering, gasping, screaming or sobbing. And even when the chorus speaks, it is not the sense of the words which is important, but the sound.38

Atmospheres, which were felt physically as a result of the lighting, music, sounds, rhythms, and even scents (released from burning torches), were key to generating the conditions necessary for the spectators to share a common sensual experience, thus greatly facilitating the establishment of a theatrical community during the course of the production. The creation of a particular atmosphere and the specifi c manner in which the masses and individuals moved in and through the space were two of Reinhardt's strategies for the appropriation of the circus space.

(3) In one review, the performance of King Oedipus is described as “something in movement, something explosive, something whipped by the wind, like a tornado, becoming fi re.”39 This was clearly the impression made by the actors' dynamic and energetic bodies, as they moved through and dominated the space. Indeed, almost all of the reviews suggest that a constant vigorous movement prevailed from start to fi nish.

Oedipus has barely found refuge in the palace when the spectacle breaks out. Torch-bearers hunt the arena ⋯, leap up the steps, disappear into the Palace. At the same time, the muf ed sound of a drum, slowly getting louder, is heard. The Palace doors open. Ten maidens burst onto the scene. They moan and sob; they twist and turn as if wracked with cramps. Some race down the steps (the speed with which they accompany this down the steep steps is amazing, worthy of the circus in which they perform). ⋯ And now on top of that, the fi ve or six hundred members of the chorus storm into the arena, running chaotically with wild gestures and bursting in with inarticulate shouting.40

The movement of the masses also set the spectators in motion. To miss as little as possible of the event, which took place not only in the arena but throughout the space, the spectators had to constantly move from one side to the other. They focused on dif erent parts and places, depending on the view they had, and this new, mobile mode of perception, which was suggested if not imposed upon the public by the mise-en-scène, brought about an individualization of the theatrical community's members.

Some commentators also considered the movements of the protagonists to be inappropriate. In his description of the Oresteia, Jacobsohn criticized “the nerve-racking mass entertainment of spectators who grew up with bull fi ghts.”41 He cited the following scene as a particularly disturbing example:

When Orestes wants to slay his mother, it is more than enough for him to rush through the door of the palace after her, restrain her by the door and push her back into the palace after the battle of words. In this production, he chases her down the steps into the arena, where he engages her in a scuf e and then drags her up the steps again much too slowly. It is dreadful.42

While the manner in which the actors' bodies were deployed certainly disgusted the critics, it was this very movement that liberated the energy needed to fi ll the space, and which carried over to the spectators. It also contributed to the creation of a community between members of a socially diverse public, as well as between performers and spectators.

The methods with which Reinhardt sought to implement “the idea of a total communion of stage and auditorium”43 had been developed in his earlier productions (the refi ned lighting, for example), but also by other

Figure 13.2 Max Reinhardt's King Oedipus, courtesy of the Institute for Theatre Studies, Freie Universität Berlin. Photo: Zander and Labisch.

representatives of the avant-garde (such as Appia's and Craig's steps). They were partially derived from forms of popular culture, including the circus, sports, cinema, and political assemblies. It was precisely to this popularizing that certain critics objected when they complained, as Jacobsohn did, of how “barbaric” and “circus-like in the most vulgar sense” Agamemnon's entrance was, accompanied “by tubas and cymbals, and actually snorting and stamping horses.”44 Reinhardt's staging of Greek tragedies (the epitome of education in bourgeois culture) in circuses (the location of popular spectacles) produced new forms of sensuality, of dynamic and energetic corporeality, and of “scattered” and “scattering” creative perception. Simultaneously, it also realized the idea of a new people's theatre, which bridged the gap between popular and elitist culture, and, over the course of the performance, successfully transformed individuals from otherwise disconnected social backgrounds into members of a single community.

Although Reinhardt always argued that his theatre was apolitical, an assessment largely shared by his contemporaries, the manner in which it enabled a communal experience between individuals of dif erent social classes, strata, and milieus gave it an undeniable political dimension. This can also be said of the way in which the new division of space allowed, or perhaps even forced, spectators to participate in the performance. As previously noted, this theatrical community was limited in time. Membership was not obligatory, nor was exclusion by others possible. It could not demand a commitment of any form, and it was not in a position to impose sanctions on deviants or defectors. It would be valid to question whether such a community is indeed the only type feasible in a democratic and heterogeneous society.

After the end of World War I, the architect Hans Poelzig converted the Circus Schumann into Reinhardt's Groβes Schauspielhaus (Theatre of the Five Thousand). The new theatre was inaugurated with a performance of the Oresteia. Unlike in 1911, when the third part, The Eumenides, was omitted and the focus therefore placed on the violence and counter-violence of ancient Greece, Reinhardt now staged, in what was ef ectively a new and democratically constituted society, the institution of the Aeropagus and the first ever democratic decision.

However, the premiere of 1919 demonstrated that the new people's theatre, until then enthusiastically received and celebrated, could no longer function under the given political and social conditions. In his review of the opening performance, the critic Stefan Grossmann described the problem as follows:

The image of a community of thousands was wonderful and heartrending. Perhaps all the more heartrending for the intellectual German citizen because the spatial unity of the masses reawakened his yearning for an inner sense of belonging. Can we be one people? Here sits Herr Scheidemann, over there privy councilor Herr Roethe, there is Haupt-mann's Goethe-like head, over there Dr. Cohn waves to a comrade. But Schneidemann looks past Roethe and Cohn passes Hauptmann with only a shrug of the shoulders. Even outside the work environment there is no feeling of unity. There is no nation on earth which so lacks a feeling of community and the war has consumed us even more. ⋯ So we have the greatest people's theatre, but no people.45

It was left to the performance to transform this gathering of hostile or merely indif erent individuals into members of a community and to generate, for as long as the performance lasted, the very sense of community that they so lacked in their social lives.

In each of the three examples, the departure from established theatres and the appropriation of new spaces represented a reaction to crises generated by bursts of modernization in society. Despite dif erent objectives and different ideological and political orientations, Wagner, Parker, and Reinhardt shared the conviction that performances could play a role in overcoming crises only if they took place within a festival or if they were able to create a festive spirit. Wagner's performances, which would frequently last several days and always took place far removed from large cities, themselves constituted the festival. Pageants were festivals bound to specific locations and related to their history. And, according to Reinhardt, every single production should be made into a festival, for the “true purpose” of the theatre was to realize its potential as a “festive play.”46

Festivals are generally characterized by a double dialectic: liminality and periodicity, on the one hand, regulation and transgression, on the other. The first opposition concerns the relation to time: Festivals recur regularly and are embedded in a day-to-day routine, but they nonetheless enable a temporal transcendence, for they forge their own temporality, which breaks with normal daily time. The second opposition concerns the action in a festival: Although it is subject to regulation, the quintessence of a festive action consists in the transgression of certain rules, namely those that impose constraints on daily life.

Because of this double dialectic, festivals appear to be the genre of cultural performance most capable of leading to the formation of new communities or to the reinforcement of existing ones. Festivals have a specifi c way of producing the social bond for which Durkheim searched. The indissoluble link between theatre and festival in the three cases discussed in this chapter underlines the specifi c function ascribed to performances. To ensure that it was ef ectively carried out, a specifi c space, able to contribute a festive and exceptional atmosphere, had to be found—as was the case with the authentic historical locations of pageants—or created—like the festival house in Bayreuth. But above all, this space had to be appropriated using strategies that favored the establishment of communities and the involvement of each and every one of the participants. The layout of the dimly lit auditorium in Bayreuth; the joint processions to performance locations, and the joint parades and chanting during pageants; the three Reinhardtian practices for the occupation and control of space by the masses, the creation of atmospheres, and the institution of dynamic and energetic bodies: These were all strategies that transformed space into festival space, in which the participants felt and acted like members of a community.

This novel association of theatre and festival was developed further in the period between the two world wars. It occurred in the mass spectacles of the newly born Soviet Union at the beginning of the 1920s; in the performances held in the framework of the workers' festivals in the Weimar Republic; in the Thingspiel plays during the first years of the National Socialist regime in Germany (1933–1936); in the restaging of medieval passion plays before the Notre Dame in Paris (for example, Arnould Gréban's Le vrai mystère de la passion); in the Swiss mass spectacles, which were based on traditional eighteenth-century folk festivals and which took place at historically important locations as part of the “spiritual defense of the country” (geistige Landes-verteidigung); and in the Zionist pageants in America (1933–1946). But in all of these, the objective was not simply, as with Reinhardt's mass performances, to create theatrical communities. Rather, these performances sought to establish specifi c ideological, religious, or political communities that would survive for longer than merely the duration of the performance itself. Nonetheless, they employed many of the strategies of spatial appropriation developed by Reinhardt in his mass performances.47 Although the resulting communities were partially self-organizing and self-organized, their underlying ideologies, religions, or political worldviews meant that strict regulatory mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion, which had been notably absent from Reinhardt's theatrical communities, generally prevailed.

1. Richard Wagner, “Art and Revolution,” in Richard Wagner's Prose Works, trans. William A. Ellis (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1895), vol. 1, 47.

2. Ibid., 34.

3. Ibid., 53.

4. Ibid., 52.

5. Ibid., 57.

6. Richard Wagner, “The Art-Work of the Future,” in Wagner, Prose Works, 100.

7. Wagner, “Art and Revolution,” in Prose Works, 52.

8. Richard Wagner, “Das Künstlertum der Zukunft,” in Julius Kapp (ed.), Richard Wagners Gesammelte Schriften (Leipzig: Hesse & Becker, 1914), vol. 10, 212–213.

9. Wagner, “Art and Revolution,” in Prose Works, 42.

10. Ibid., 52–53.

11. Quoted in Martin Gregor-Dellin, Richard Wagner— die Revolution als Oper (Munich: Hanser, 1973), 56–57. Emphasis in the original.

12. Quoted in Barry Millington, The New Grove Guide to Wagner and His Operas (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

13. Richard Wagner, “Ein Einblick in das heutige deutsche Opernwesen,” in Richard Wagners Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 9, 340.

14. http://www.tchaikovsky-research.net/en/Works/Articles/TH314/index.html (accessed May 22, 2012).

15. Martin Gregor-Dellin and Dietrich Mack (eds.), Cosima Wagner: Die Tage-bücher 1869–1883 (Munich: Piper, 1976/1977), vol. 1, 323.

16. Wagner, in Richard Wagners Gesammelte Schriften, vol. 9, 328.

17. Richard Wagner, Letter to Ludwig II on 28. November 1880, quoted in Caroline V. Kerr (ed. and trans.), The Bayreuth Letters of Richard Wagner (Boston: Small, Maynard, 1912), 362–363.

18. Quoted in Robert Withington, English Pageantry: A Historical Outline (New York: Benjamin Blom, 1963), vol. 2, 195.

19. Cf. Émile Durkheim's doctoral dissertation The Division of Labor in Society (New York: The Free Press, 1964 [1893]).

20. Durkheim, The Division of Labor in Society, 172.

21. Louis N. Parker, Several of My Lives (London: Chapman and Hall, 1928), 285–286.

22. Louis N. Parker, “What Is a Pageant?” New Boston, November 1, 1910, p. 296.

23. Joshua Esty, “Amnesia in the Fields: Late Modernism, Late Imperialism and the English Pageantry-Play,” ELH 69:1 (2002), 245–276, 248.

24. Parker, Several of My Lives, 280.

25. Esty, “Amnesia in the Fields,” 248.

26. David Glassberg, American Historical Pageantry: The Uses of Tradition in the Early Twentieth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990), 283.

27. Percy MacKaye, The Civic Theatre in Relation to the Redemption of Leisure: A Book of Suggestions (New York: Mitchell Kennerley, 1912), 15.

28. Glassberg, American Historical Pageantry, 283.

29. Ibid., 285.

30. Quoted in ibid., 84.

31. Cf. Martin Green, New York 1913: The Armory Show and the Paterson Strike Pageant (New York: Scribner, 1988).

32. Quoted in Gusti Adler, Max Reinhardt und sein Leben (Salzburg: Festungs-verlag, 1964), 43.

33. Max Reinhardt in Das literarische Echo 13 (1910/1911), quoted in Hugo Fetting (ed.), Reinhardts Schriften. Briefe, Reden, Aufzeichnungen, Interviews, Gespräche und Auszüge aus Regiebüchern (Berlin: Henschelverlag, 1975), 331.

34. Fritz Engel, Berliner Tageblatt (November 8, 1910).

35. Norbert Falk, BZ am Mittwoch 262 (November 8, 1910), quoted in Erika Fischer-Lichte, Theatre, Sacrifice, Ritual: Exploring Forms of Political Theatre (New York: Routledge, 2005), 50.

36. Alfred Klar, “Review of Max Reinhardt's Oresteia,” Vossische Zeitung (October 14, 1911), translated by Saskya Iris Jain in Erika Fischer-Lichte, The Transformative Power of Performance: A New Aesthetics (London: Routledge, 2008), 33.

37. According to Gernot Böhme, atmospheres are neither purely subjective nor purely objective. Atmospheres are not so much the product of a particular interpretation. Rather, they are things that are felt physically and that emanate from objects, people, and constellations within space. Whoever experiences an atmosphere is not suddenly confronted with it but quite literally immersed in it. Atmospheres strengthen the sensual and af ective component of reception and can therefore weaken the cognitive aspects. Cf. Gernot Böhme, Atmosphäre: Essays zur neuen Ästhetik (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1995), and Sabine Schouten, Sinnliches Spüren: Wahrne-hmung und Erzeugung von Atmosphäre im Theater (Berlin: Theater der Zeit, 2007).

38. Fischer-Lichte, Theatre, Sacrifice, Ritual, 57.

39. Fritz Engel, Berliner Tageblatt (November 8, 1910).

40. Paul Goldmann, Neue Freie Press, November 1901, quoted in Fischer-Lichte, Theatre, Sacrifice, Ritual, 60.

41. Ibid., 62.

42. Siegfried Jacobsohn (1912), translated by Saskya Iris Jain, quoted in Fischer-Lichte, The Transformative Power of Performance, 35.

43. Emil Faktor, Berliner Börsen-Courier 558 (November 29, 1919).

44. Jacobsohn, quoted in Fischer-Lichte, The Transformative Power of Performance, 51.

45. Stefan Grossmann, quoted in Fisher-Lichte, Theatre, Sacrifice, Ritual, 68.

46. Cited in Arthur Kahane, Tagebuch des Dramaturgen (Berlin: Aufklärung und Fortschritt, 1928), 119 f .

47. Cf. Fischer-Lichte, Theatre, Sacrifice, Ritual.

Adler, Gusti, Max Reinhardt und sein Leben, Salzburg: Festungsverlag, 1964.

Böhme, Gernot, Atmosphäre: Essays zur neuen Ästhetik, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1995.

Durkheim, Émile, The Division of Labor in Society, New York: The Free Press, 1964 [1893].

Engel, Fritz, n.n., Berliner Tageblatt, November 8, 1910.

Esty, Joshua, “Amnesia in the Fields: Late Modernism, Late Imperialism and the English Pageantry-Play,” ELH 69:1, 2002, 245–276.

Faktor, Emil, n.n., Berliner Börsen-Courier 558, November 29, 1919.

Fetting, Hugo (ed.), Reinhardts Schriften. Briefe, Reden, Aufzeichnungen, Interviews, Gespräche und Auszüge aus Regiebüchern, Berlin: Henschelverlag, 1975.

Fischer-Lichte, Erika, Theatre, Sacrifice, Ritual: Exploring Forms of Political Theatre, New York: Routledge, 2005.

Fischer-Lichte, Erika, The Transformative Power of Performance: A New Aesthetics, trans. Saskya Iris Jain, London: Routledge, 2008.

Glassberg, David, American Historical Pageantry: The Uses of Tradition in the Early Twentieth Century, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990.

Green, Martin, New York 1913: The Armory Show and the Paterson Strike Pageant, New York: Scribner, 1988.

Gregor-Dellin, Martin, Richard Wagner—die Revolution als Oper, Munich: Han-ser, 1973.

Gregor-Dellin, Martin and Mack, Dietrich (eds.), Cosima Wagner: Die Tagebücher 1869–1883, Munich: Piper, 1976/1977.

Kahane, Arthur, Tagebuch des Dramaturgen, Berlin: Aufklärung und Fortschritt, 1928.

Kapp, Julius (ed.), Richard Wagners Gesammelte Schriften, Leipzig: Hesse & Becker, 1914.

Kerr, Caroline V. (ed. and trans.), The Bayreuth Letters of Richard Wagner, Boston: Small, Maynard, 1912.

MacKaye, Percy, The Civic Theatre in Relation to the Redemption of Leisure: A Book of Suggestions, New York: Mitchell Kennerley, 1912.

Millington, Barry, The New Grove Guide to Wagner and His Operas, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Parker, Louis N., Several of My Lives, London: Chapman and Hall, 1928.

Parker, Louis N. “What Is a Pageant?” New Boston, November 1, 1910, available online: http://www.archive.org/stream/newbostonchronic00bost/newboston-chronic00bost_djvu.txt accessed May 22, 2012.

Schouten, Sabine, Sinnliches Spüren: Wahrnehmung und Erzeugung von Atmosphäre im Theater, Berlin: Theater der Zeit, 2007.

Wagner, Richard, Prose Works, trans. William A. Ellis, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1895.

Withington, Robert, English Pageantry: A Historical Outline, New York: Benjamin Blom, 1963. http://www.tchaikovsky-research.net/en/Works/Articles/TH314/index.html (accessed May 22, 2012).