Based on the 2005 novel by Cormac McCarthy, No Country for Old Men gives vivid expression to the novelist’s nihilistic vision of the darkness in the new West. Set in west Texas, 1980, its narrative concerns the destinies of three men whose paths cross and collide, altering the course of their lives irrevocably. The first of these is Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), a working-class cowboy who by chance stumbles upon an abandoned fortune of drug money and decides to risk its theft. Moss is pursued by Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), an enigmatic hit-man engaged by the drug cartel to retrieve the money Moss has stolen. Moss is a skilled ex-military marksman, a hunter, but to protect his stolen fortune he must go on the run, become the hunted instead of the hunter. Chigurh is also a hunter, pursuing Moss relentlessly, an unstoppable force, menacing in his cold and methodical purpose. A third hunter, local sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), investigates the gangland shoot-out that put the money into Moss’s hands, following the chase, always one step behind, and always dreading the moment of fatal confrontation. One of these three meets his fate in violent death, another is inexplicably spared. The third has no fate, for he is fate itself, or the shape it assumes in these times when ‘signs and wonders’ have again become the sole reliable codex of a civilisation in decline.

In the years immediately preceding the release of No Country for Old Men, the Coen brothers had enjoyed moderate box-office success with two comedies, Intolerable Cruelty (2003), a contemporary screwball, and The Ladykillers (2004), a remake of Alexander MacKendrick’s 1955 British comedy. The critics had few kind words for these films and during this period it was generally thought that the Coens weren’t living up to the promise of their earlier achievements. The critics’ ill mood passed in 2007 with the premiere of No Country for Old Men. After Fargo more than a decade earlier, No Country for Old Men became the Coens’ second break-out hit, a film that generated significant box-office returns as well as garnering top accolades and awards including Academy Awards for Best Picture, Best Direction, Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Supporting Actor (Javier Bardem). Upon its theatrical release, No Country for Old Men was almost unanimously acclaimed as a major cinematic achievement. In Peter Travers’ estimation the film was nothing less than ‘a new career peak for the Coen brothers’. New York Times reviewer A. O. Scott praised the movie’s ‘brilliant technique’, citing the Coens’ ‘ruthless application of craft’ to shape a film that is, for formalists, ‘pure heaven’. Roger Ebert thought it was ‘as good a film as the Coen brothers have ever made’. Comparing it with Fargo, he writes: ‘To make one such film is a miracle. Here is another.’ There was generally high praise for the Coens’ adaptation of McCarthy. Writing for Time Out, Geoff Andrew considered the screenplay so attuned to McCarthy’s novel it seemed like an original written by the Coens. Peter Rainer thought that No Country for Old Men’s ‘dizzying alternations of comedy and horror’ branded it unmistakably as a Coen brothers movie. From a somewhat different vantage, Lisa Schwarzbaum thought the Coens had finally surrendered the ‘hypercontrolling interest in clever cinematic style’ that had marred their previous films. Geoffrey O’Brien echoed this thought, describing the film as one that draws its power precisely from the filmmakers’ stylistic restraint, ‘deliberately holding in check the invention that flourishes so exuberantly elsewhere in their work’. In No Country for Old Men, thinks O’Brien, ‘the Coens rigorously deny themselves most of the gratifications associated with the phrase “a Coen brothers movie”’.

Despite widespread acclaim, some reviewers still had doubts. Veteran reviewer David Denby of the New Yorker wrote that ‘No Country for Old Men is the Coens’ most accomplished achievement in craft’ but he thought there were ‘absences’ in the movie that ‘hollow out the movie’s attempt at greatness’. These absences seem to consist of gaps in character credibility and the unceremonious elimination of Moss without the dignity of a proper death scene. Stephen Hunter was completely unimpressed, admitting bluntly, ‘I just don’t like it much’, although like many he praised the film for its flawless cinematic craftsmanship. Hunter’s main complaint concerned character development, of which he thought there was very little. In his view the Coens had reduced their characters to one-dimensional stereotypes, assigning to each a simplistic moral or symbolic attribute: Chigurh as the menace of death or evil, Carson Wells (Woody Harrelson) as pride and Sheriff Bell in the part of ‘Melancholy Wisdom’. Andrew Sarris, another veteran movie critic, seventy-eight years old when he wrote his review, expressed strong disapproval, refusing to take the film seriously because that would be, in his words, ‘an exercise in cosmic futility’. Perhaps No Country for Old Men is no movie for old men.

Adapting McCarthy

Unlike their previous screenplays which draw, often indiscriminately, on a multiplicity of literary and cinematic sources, No Country for Old Men is a direct adaptation of McCarthy’s novel, honouring a writer many consider the greatest living American author. Here for the first time the Coen brothers exchange their postmodern technique of ‘free adaptation’ for conventional fidelity to a single literary source. The Coens must have seen something of themselves in McCarthy’s writing, a kindred storyteller with an approach to crime fiction that matched their own philosophy and worldview. As a direct adaptation of a contemporary literary source, the Coens’ No Country for Old Men is an anomaly among their works. McCarthy is one of only two living writers the Coens have chosen to adapt (the other is Charles Portis, author of True Grit). Otherwise, the brothers have not expressed interest in filming contemporary literature, though McCarthy can be considered a special case. By the time the Coens got around to adapting his novel in 2007, he had already become a kind of institution among the literati, the recipient of many awards, including the National Book Award for his novel All the Pretty Horses (1992) and the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for The Road (2006), and therefore eligible for inclusion in the Coens’ pantheon of ancestral writers, joining the likes of Hammett, Cain, Chandler, Odets and West, all of them writers of the 1930s and 1940s.

In choosing to adapt McCarthy, the Coen brothers forego their characteristic ironic detachment and, via McCarthy, assume a more earnest stance toward the story. Generally, the Coens avoid displays of seriousness, deflating any hint of sincerity in their works with irony and comic absurdity. But in the case of No Country for Old Men they surrender authorial control to the literary source (which takes itself seriously enough), allowing them to assume another’s view of American society without claiming it as their own. Further reasons for choosing to adapt McCarthy are rooted in the strong affinity between McCarthy and the Coens as storytellers, a unique attraction that can be traced to a number of shared authorial preoccupations. The first of these is no doubt their shared interest in the ‘dark side’ of the human spirit, made frighteningly real in McCarthy’s nihilistic saga of human iniquity. We have seen it before in Coen brothers films, this darkness, especially in Blood Simple and Fargo, two closely related precursors of No Country for Old Men. We have seen characters very much like Sheriff Bell, too, whose mystified incomprehension of human degeneracy differs from that of police chief Marge Gunderson only as a matter of geography.

McCarthy’s is a vision of darkness in the West, the American southwest, a region that has long had exotic appeal for the Coen brothers dating back to the early days of Blood Simple, making McCarthy’s barren desert landscape familiar territory for the Coens. The chase unfolds in the towns and cities of west Texas along the southern border traced by the Rio Grande: Sanderson, Del Rio, Eagle Pass, Odessa and El Paso. Shooting on location in the barren expanses of west Texas and New Mexico, the filmmakers found settings and imagery suited to rendering McCarthy’s concrete and detailed descriptions of topography, terrain and climate. The desert backdrop for Sheriff Bell’s opening voiceover is a striking visualisation of McCarthy’s landscape, revealing the rugged Texas outland in a tableau of eleven stationary shots surveying the countryside, each one an extreme long shot isolating a different perspective of the barren and formidable Texas back country, but taken together forming an image of vast emptiness inhospitable to human life. This is a view of the world as it had been for thousands of years, as it was in the days of the ‘old timers’ and still is, despite all human efforts to tame it – a country unchanged and unconquered by man.

In the Coens’ imagination Texas assumes a set of mythological connotations. Recalling the setting of Blood Simple, Joel Coen stresses that it was not intended to represent Texas as it exists today, but rather ‘something preserved in legend, a collection of histories and myths’ (Allen 2006: 26). The Texas of McCarthy’s story also suggests something legendary preserved in its far western territories, where vast desert expanses are rimmed by distant mountains to shape a landscape of heroic dimensions in which myth and legend are readily born and nurtured. McCarthy’s novel evokes the aura of myth potently in the figure of Anton Chigurh, but it also tells with blunt realism the story of the people of Texas, tough survivors in a ‘hard country’ that grinds its weaker inhabitants into the hardened caliche. Beyond the territories of McCarthy’s Texas a much bigger story unfolds, the story of the ‘hard country’ of contemporary America and the new hardships its belated western settlers must endure, casting a rueful eye on the historical growth of the nation and its cultural deterioration in the late twentieth century. In this sense, the decision to adapt No Country for Old Men is perfectly consistent with the Coen brothers’ oft-repeated self-description as ‘American filmmakers’ dedicated to making films in and about the United States of America.

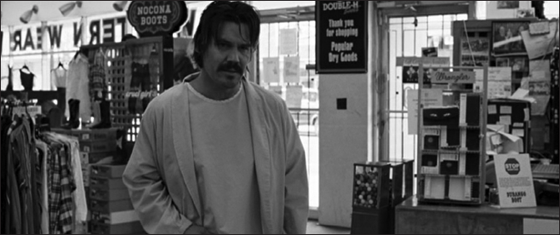

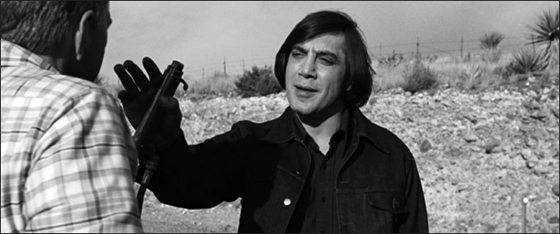

The Coens’ adaptation of No Country for Old Men maintains a respectful degree of fidelity to the original. Most of the novel’s narrative as well as its central characters and themes have been preserved. Originally conceived and written as a screenplay, the novel has a fundamentally cinematic structure well suited to adaptation and well matched with the interests and talents of the Coen brothers. As an adaptation, the Coens’ movie renders McCarthy’s novel with admirable economy. The density and pace of the novel’s narrative is smoothly translated to the screen with skillful editing, done as always by the brothers themselves (still credited to their fictional film editor of long-standing, Roderick Jaynes). Some of the movie’s most memorable dialogue is transcribed unaltered from the novel, such as Sheriff Bell’s folksy comment on the aftermath of the desert drug deal gone wrong: ‘If this ain’t the mess, it’ll sure do til the mess gets here.’ The regional dialect, so prominent in the dialogue of the novel and always fascinating to the Coens, is reproduced in the movie with careful attention to authenticity. McCarthy’s tough westerners are also given shape and life by intelligent casting. Tommy Lee Jones was chosen for the role of Sheriff Bell because his aging, weathered face (seen previously in many westerns) and earthy gravitas brought dignity to the part, and because, as a native of west Texas, he speaks the local dialect naturally. Josh Brolin, also a native of west Texas where he grew up on a horse ranch, seemed equally well suited to play the cowboy-adventurer Moss. In his Academy Award-winning performance as Chirgurh, Javier Bardem brings uncanny menace to his characterisation of a rogue hit man who is, in Joel’s words, ‘like the man who fell to earth’, so alien is his presence in the story’s setting. His accent and ethnic identity are not readily identifiable, his hairstyle odd and unsettling, his clothing somehow out-of-place. ‘He’s the thing,’ remarks Joel, ‘that does not grow out of the landscape’ (Hirschberg 2007).

Though for the most part faithful to the novel, the Coens embellish McCarthy’s story with additional narrative elements, such as the pit bull that chases Moss in the river and nearly kills him. The Coens’ imprint is particularly noticeable in the touches of humour added to McCarthy’s tale, like the cranky mother-in-law with cancer, prone to obtuse utterances like: ‘It’s not often you see a Mexican in a suit,’ or the substitution of Mexican street musicians improbably serenading a wounded Moss in the early dawn, instead of the solitary street sweeper of the novel who encounters Moss on his morning rounds. The filmmakers’ presence is also evident in minor flourishes, like the facial expressions of actor Bardem as he admonishes the frightened gas station owner to keep his lucky quarter separate, otherwise it just becomes another coin, ‘which it is’. As if he can think of no other words to convey his profundity, he simply raises his eyebrows in a gesture that says, ‘Think about it. This is meaningful.’ One of the most noticeable editorial nuances occurs at the very end of the movie with the clock that ticks ominously after Bell finishes recounting his dreams, reminding him that (as he says himself and knows perfectly well) ‘time is not on my side’.

Another allure of McCarthy’s novel is its reliance on (and departures from) the generic structures of crime fiction, which play to the Coen brothers’ preference for adapting pulp fiction. Generically, No Country for Old Men is a notable departure from McCarthy’s previous work, although the novelist had previously explored neighboring territory in his masterpiece Blood Meridian (1985), another story of criminal violence and inhuman savagery along the Tex-Mex border, anno 1849. As a crime story McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men may even owe something to Coen favorite James M. Cain. The similarities with Cain’s fiction are noticeable in McCarthy’s terse, ‘hardboiled’ dialogue that translates Cain’s southern California vernacular into cowboy slang. The novel’s fast-paced plotting also resembles Cain’s technique, as does the focus on Moss, an ordinary guy tempted by greed to enter into dangerous circumstances that quickly spin out of control. The Coens called it an action movie, or at least as they said, ‘it’s the closest we’ll ever come to making an action movie’ (DVD extra, ‘The Making of No Country for Old Men’). Pressed by interviewers to specify its genre, the brothers vacillated. They and some cast members suggested various possibilities: chase, western, noir. Because of the film’s excessive violence and its light treatment thereof, Tommy Lee Jones called it a ‘comedy horror’.

Among the generic models suggested, two distinguish themselves most: film noir and western. Clearly, these are the operative terms defining the movie’s hybrid form. Despite the contemporary time frame, the desert setting of west Texas and the images of lawmen on horseback recall stock elements of the Hollywood western. Ed Tom Bell is a Texas sheriff in pursuit of outlaws who threaten the citizens he is sworn to protect. As a lawman on the eve of retirement who has lost his self-confidence and feels ‘overmatched’ by the outlaws, Sheriff Bell evokes Marshal Will Kane (Gary Cooper) in Fred Zinnemann’s classic western High Noon (1952). Chigurh recalls the classic villain: a sinister hired gunman dressed in black and given to sadistic violence in the tradition of Jack Wilson (Jack Palance), the psychopathic gunslinger in Shane (George Stevens, 1953). The style of clothing clearly identifies the characters as westerners. Cowboy hats, saddle boots and Wrangler jeans are de rigeur. In No Country for Old Men, as always, the Coens pay special attention to wardrobe, especially to the boots worn by male characters. Moss wears Larry Mahans, not flashy, but very durable and functional, like Moss himself. Chigurh wears alligator boots because, as costume designer Mary Zophres explains, they wanted his boots to look ‘bumpy, gross, and pointy, [like] they could kill somebody’ (DVD extra, ‘Working with the Coen Brothers’). Carson Wells wears expensive and stylish Lucchese crocodile boots as befits a ‘day trader’ whose interest in his work is strictly economic and opportunistic, unlike Chigurh, whose only interest seems to be dealing death to all in his path.

Weapons are another indispensable part of the western’s iconography. In the old West they used six-shooters and Winchester repeating rifles. In the new West these are replaced with an impressive military arsenal: Tec 9 automatic machine guns, shortbarreled Uzis, automatic shotguns with drum magazines. Moss hunts antelope with a .270 Mauser equipped with a telescopic sight, the type of rifle used by snipers in the Vietnam War. Sheriff Bell prefers the old-style lever-action Winchester model 97, but expresses great admiration for the old-timers who didn’t need to carry a firearm. Chigurh’s weapons are exotic customised killing tools, the most unusual being the captive bolt pistol, a tool used to slaughter cattle, which he applies to his human victims as if they are nothing more than animals. Yet, for all this attention to weaponry, the gunfights in No Country for Old Men are limited. Gunfights (referred to by Moss as ‘shootouts’) occur onscreen only twice – once when drug dealers pursue Moss across the desert at night and again when Moss and Chigurh shoot it out at Eagle Pass. We do witness the aftermath of the ‘colossal goat fuck’ in the desert, or what Bell’s deputy refers to as the ‘Wild West’ (and are thus invited to imagine the carnage), and we see, very briefly, the cartel shooters fleeing from Moss’s murder at the El Paso motel, but for a movie that plays like a western, actual gun battles are relatively few. The most explicit and egregious acts of violence are carried out by Chigurh in his executions. Indeed, the first scene of the movie in which he strangles a deputy with handcuffs is probably the most visceral violence in either book or movie. As at least one commentator has suggested, this scene and other acts of cold-blooded murder add an element of horror, created by the filmmakers’ unblinking portrayal of excessive violence (Landrum 2009: 200).

The Coen brothers have said that what they like best about McCarthy’s novel is its subversion of the western genre. One of several major breaches of genre convention concerns ‘the showdown’. In the typical western a final showdown is the dramatic climax in the struggle of good versus evil, where the good ultimately prevails. No Country for Old Men thwarts the genre’s promise of a final showdown between Chigurh and Bell. In fact, they never meet face to face. The sheriff, always a step behind, fails to track down his man, whom he believes to be a ‘ghost’. Even the showdown between Moss and Chigurh in Eagle Pass ends in a draw, both of them wounded and limping from the scene – Moss to a Mexican hospital, Chigurh to a cheap motel room where he tends to his wounds unassisted, acquiring the necessary medications by coolly staging a car explosion outside a pharmacy and casually strolling off with stolen drugs. Chigurh displays several key attributes that subvert generic expectations for the western villain. The generic outlaw is driven by lust for money (a bank robber or bandit) and, lacking a moral code, will resort to violence and murder to get what he wants. Chigurh is not interested in money or material things. He uses violence as a tool for administering his twisted sense of justice. As Carson Wells describes him, ‘He’s a peculiar man. You could even say he has principles. Principles that transcend money or drugs or anything like that,’ adding, ‘He’s not like you. He’s not even like me.’ Chigurh adheres to a code of ethics which, though incomprehensible to others, he upholds with the dedication and personal integrity conventionally associated with the western hero. In a sense, Chigurh defines himself as a lawman, an agent of some quasi-divine constabulary authorised by some unknown power to administer punishment to those who violate his cryptic principles. Moss, the character we would like to imagine as the hero, is an opportunistic thief who has taken advantage of the cartel’s criminal blunder. As narrator, Bell is authorised to deliver the moral of the story and thus positioned to fulfill the genre’s demand for a strong patriarchal hero who intervenes to rescue Moss and defeat Chigurh. But as the story unfolds it becomes increasingly apparent that Bell’s efforts to protect ‘his people’ are futile. In the end he seems little more than a worn and defeated relic of old-fashioned law enforcement who hopes to avoid rather than capture his formidable antagonist and who in the end cannot protect Moss (whom he calls ‘his boy’) from the fatal consequences of his actions. All in all, Sheriff Bell does not cut a very heroic figure.

What Makes a Man?

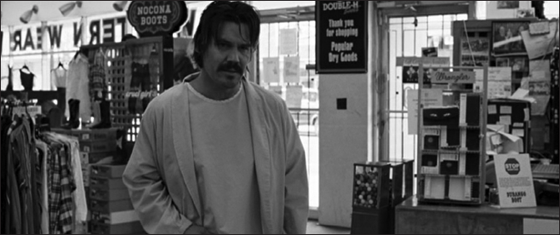

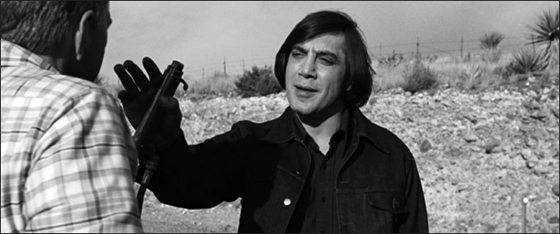

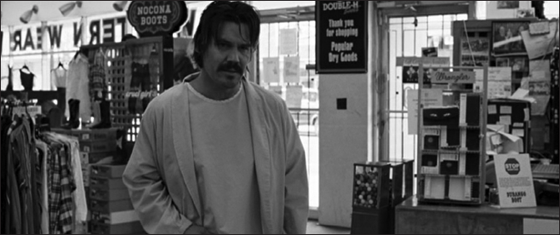

The question of manhood – ‘What makes a man?’ – is posed repeatedly in the films of the Coen brothers. It is one of their most central thematic preoccupations, explicit or implied in every one of their stories. It is asked of the Dude in The Big Lebowski, where the problems of masculine identity are given parodic scrutiny, and in The Man Who Wasn’t There, where the question becomes an accusation: ‘What kind of a man are you?’ In No Country for Old Men the question of manhood is linked with the western genre’s focus on violence and domination as defining features of masculinity. To be a man in the old West one had to fight – fight to defend the innocent from villainous outlaws, fight off attacks by indigenous tribes, subdue the harsh wilderness and bring it under human control. Victory over the forces of adversity by violent means is a defining feature of the western male hero. In the inimical world of the western frontier, the power to subdue and control adversarial forces is the male hero’s greatest virtue. As Stacy Peebles writes, based on themes of conquest and control, the western genre is ‘the ultimate venue for the display of male power’ (2009: 125). Similar preoccupations with masculine identity are definitive of film noir, another classic American genre that defines manhood in terms of violence and control. Indeed, the private detectives of classic film noir provide models of masculinity distinctly similar to the western hero. Like the rugged protagonists of the western, noir detectives are tough, hard-boiled; they can take a beating as well as give one. Incarnated in characters like Hammett’s Sam Spade and Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, these are rough and ready men not easily intimidated by the threat of violence. They keep their cool and control the situation. Certainly, Moss fits this description. A mixture of self-reliant cowboy and battlehardened soldier, he possesses abundant physical strength and cunning and, like his adversary Chigurh, Moss is possessed of a single-minded determination; once set on a path, he is undeterred. Perhaps this is why the pit bull attack on Moss was added to the screenplay, establishing a symbolic connection between Moss and the ‘beast’ (Chigurh) who pursues him so doggedly. When wounded by Chigurh, however, Moss loses control. As he convalesces in a Mexican hospital, cared for and protected by a staff of female nurses, Moss is temporarily robbed of his masculine strength, powerless to protect himself or his wife from Chigurh’s lethal threat. The crippling wound is the outward sign of his emasculation. Thus, when he leaves the hospital he wears only a hospital gown, which gives him the feminising appearance of wearing a woman’s dress. After awkwardly explaining to a border guard his reasons for appearing in public ‘undressed’, Moss immediately goes to a Western clothing store and buys the garments appropriate for a man of the West: Mahan boots, Wrangler jeans and a Stetson hat.

‘You have a lot of people come in here without any clothes?’

The loss of manly power and control played out in No Country for Old Men parallels the crisis of male identity commonly portrayed in classic film noir, where, unlike the western’s splitting of male identity into good men and bad men, we find a wider spectrum of alternative models of masculine identity. Indeed, noir protagonists are often weak and powerless anti-heroes, either the ‘dupe’ who is manipulated and betrayed by a deceitful femme fatale, or the ‘wrong man’, an innocent victim of circumstances beyond his control. Other models of masculinity in film noir include the psychopathic killer and the damaged or traumatised man, often a veteran of war, who in his various forms exemplifies the crisis of male identity symbolised by Moss’s crippling wound. During the shoot-out in Eagle Pass Chigurh also suffers a wounded leg, which in contrast to Moss he doctors himself, thus asserting his masculine claim to autonomy, but also demonstrating his preternatural indestructibility. Chigurh’s coldly rational, machine-like manner and his total lack of emotion or sympathy are all stereotypically masculine. In this regard, his favourite weapon, the cattle-gun, is emblematic of his mechanical method of thinking and killing – pragmatic, efficient and emotionless. Anton Chigurh is also machine-like in his inflexible commitment to his so-called principles. Above all, Chigurh wants to maintain control, by whatever means necessary. As he tells Carla Jean after she insists that ‘you don’t have to do this’, Chigurh cannot make himself ‘vulnerable’. ‘I have only one way to live,’ he says. ‘It doesn’t allow for special cases.’ As much as Chigurh enjoys demonstrating the uncertainty of life to others, he himself is possessed of a supreme certainty. Thus, when Wells tries to save himself from Chigurh by revealing the location of the satchel containing $2 million, saying, ‘I know where it is,’ Chigurh replies, ‘I know something better. I know where it’s going to be.’ ‘Where’s that?’ asks Wells. ‘It will be brought to me,’ answers Chigurh, ‘and placed at my feet.’ When Wells protests, ‘You don’t know that to a certainty,’ Chigurh retorts: ‘I do know that to a certainty.’

Sheriff Ed Tom Bell represents the traditional ideal of masculinity. As a patriarchal protector he assumes responsibility for defending his community. His resolve, however, is weakened by an underlying fear of his inability to stop Chigurh and eliminate the threat the killer presents to the people he is sworn to protect. More than his own weakness, Bell fears the failure of patriarchal authority, the breakdown of the old system and its values, a breakdown he cannot comprehend and thinks he can no longer fix or control. There are indications that he no longer takes himself seriously as an active agent of the law. At various points in the story Bell mocks himself and the stereotypes associated with masculinity. When, for instance, he and Deputy Wendell (Garret Dillahunt) prepare to enter Moss’s abandoned trailer home to investigate, Bell says to his younger partner, ‘You go in first. Gun out and up!’ The deputy asks, ‘What about yours?’ ‘I’m hiding behind you,’ says Bell with a cynical grin. During their previous investigation of the desert shoot-out between rival drug dealers, Bell’s coolly rational assessment of the crime scene prompted Wendell to compliment the sheriff on his ‘linear thinking’. Bell’s off-hand quip is openly self-deprecating: ‘Old age flattens a man.’ In the voiceover prologue that begins the film Bell gives a brief history of his family as lawmen: ‘My grandfather was a sheriff, my father, too. Me and him was sheriff at the same time, him up in Plano and me out here. I think he was pretty proud of that. I know I was.’ He notes in particular his admiration for the ‘old-timers’, wondering how they might have ‘operated these times’, thus establishing an unbroken succession and a strong sense of identification with the patriarchal tradition. Bell’s prologue also includes an anecdotal recollection of a boy he sent to the gas chamber for killing a fourteen-year-old girl who said he’d do it again if he could and that he knew he was going to hell. Bell’s mystified comment, ‘I don’t know what to make of that. I surely don’t,’ establishes him as the voice of an older generation no longer able to take the measure of declining moral values in a rapidly changing and increasingly secular and permissive society.

Bell is depicted as a frightened man confronting his worse fears. It isn’t death he fears so much as being defeated in his struggle against the rising tide of pathological evil embodied in Chigurh, of whom he says ‘I don’t want to push my chips forward and go out and meet something I don’t understand. A man would have to put his soul at hazard. He’d have to say “Okay, I’ll be part of this world”.’ Bell never actually accepts his part in this world. He longs for a past when police officers protected their flocks as gentle shepherds and had no need to carry firearms. In his long years of law enforcement he has seen the worst in humanity, but still refuses to acknowledge its existence. The world he once knew, the world of his forefathers, is disappearing and he cannot comprehend or control the forces of change.

No Country for Old Men’s similarity to Fargo is often cited, with good reason. The basic premise of both films is the same: a small-town sheriff must confront psychopathic killers whose violent intrusion into an otherwise peaceful provincial locale seems inexplicable to local law enforcement. Chigurh has a precursor in the figure of Gaear Grimsrud, who is but one in a series of psychopaths populating Coen movies including Loren Visser of Blood Simple, Eddie Dane of Miller’s Crossing and Karl ‘Madman’ Mundt of Barton Fink. In both Fargo and No Country for Old Men the story centres on a provincial law officer who cannot comprehend the motives for the outrageous acts of violence they commit. Like Marge Gunderson, Sheriff Bell is at a loss to explain the bodies that keep piling up. Discussing the shootout at the motel and Moss’s death, Bell’s colleague exclaims: ‘It’s beyond everything. Who would do such a thing? How do you defend against it?’ When Deputy Wendell asks ‘Who the hell are these people?’ Bell comments laconically, ‘I ain’t sure we’ve seen these people before. Their kind. I don’t know what to do about them even.’

When asked how dangerous he thinks Chigurh is, Carson Wells replies, ‘Compared to what? The bubonic plague? He’s bad enough that you called me. He’s a psychopathic killer, but so what? There’s plenty of them around,’ punctuating his statement with a slight, self-satisfied smirk indicating that he would probably consider himself one of the ‘plenty around’. Measured strictly by his actions, Chigurh fits the standard profile of the psychopathic serial killer. His total lack of emotion, even during ultraviolent acts of murder, and the complete absence of empathy for his victims are textbook symptoms of criminal psychopathy. When, in the opening scene, he strangles a deputy brutally, or later when he executes the cartel associates point blank, not a hint of emotion shows on his face. Chigurh performs his murders in ice-cold blood, like the teenage boy Sheriff Bell describes in his opening monologue who, after killing a teenage girl said ‘there wasn’t no passion to it’.

But No Country for Old Men presents us with something more than the gardenvariety psycho-killer, conjuring instead a mythic, vaguely supernatural aura around Chigurh, reinforced by Bell’s superstitious belief that he is chasing a ‘ghost’. Fully reproducing the mythic dimension in McCarthy’s writing, the Coen brothers recreate the tricky realism of the novel where reality continually threatens to reveal itself as a nightmare, evoking an atmosphere of dread rivalling that of a horror movie. As a mythic figure, Chigurh is not allegorical. He does not merely represent Death or Fate, or any abstract concept. He is far too real, too plausibly human, if only as an aberration of humanity. The mythic or supernatural aura surrounding him is created by his seeming indestructibility, but also, more significantly, by his serene transcendence of earthly concerns and his single-minded dedication to ‘higher principles’. Bell’s fear of the new kind of criminal that Chigurh represents drives him into retirement: ‘Now I aim to quit and a good part of it is knowin’ that I won’t be called on to hunt this man. I reckon he’s a man.’ The Coens further enhance Chigurh’s ghostly aspect in the scene at the Desert Sands motel when Bell returns at night to revisit the crime scene. Knowing that the killer has returned to the scene of his crime before, Bell senses that Chigurh could be there. Indeed, we see him briefly in a dark reflection, waiting inside, hidden behind the door. Mysteriously however, when the sheriff enters to inspect the darkened room, Chigurh has vanished. No explanation, in cinematic terms, is given for his disappearance. The viewer is abandoned to speculation and uncertainty.

Each of the three central male characters – Moss, Chigurh, and Bell – presents a differing image of masculinity based on control and mastery. It begins with the early scene in which Chigurh, driving a stolen police cruiser, stops a lone driver and asks him politely, ‘Step out of the car sir, please.’ When the confused driver sees Chigurh’s cattle gun and asks, ‘What’s that?’ Chigurh repeats his request with a friendly demeanor. Raising the deadly bolt to the driver’s forehead in a gesture that suggests a priest giving his supplicant a blessing, Chigurh asks, gently, ‘Will you hold still, please?’ Immediately after the killer’s victim collapses and falls to the ground the film cuts to Moss looking through the scope of his rifle, targeting an antelope far off in the distant desert plain. Moss’s first words, directed at his prey, are: ‘You hold still.’ He shoots but only wounds the animal, which he must now track and finish off. His failure as a marksman proves fatal as it forces him to follow the antelope which eventually leads him to the scene of the desert shoot-out and to ‘the last man standing’ and the fortune in drug money. Although he perceives the risk of taking the money, Moss believes he can master the odds and control his fate. Moss’s arrogance leads ultimately to his downfall. He thinks he is smart enough and tough enough to take on Chigurh, scoffing at Carson Wells’ warning: ‘What’s this guy supposed to be? The ultimate bad-ass?’ Moss is angered by Wells’ presumption of Chigurh’s superiority and threatens: ‘Maybe he’s the one who needs to be worried.’ For both Moss and Chigurh, identity depends on their power to master and control, to make things ‘hold still’. Chigurh insists on controlling every situation, or as he puts it, remaining ‘invulnerable’, but denies all others such control, sometimes introducing the element of chance. In the end, Chigurh too is subject to the whims of chance, as dramatically illustrated by the unexpected car crash following Carla Jean’s murder. Bell promises to ‘make Moss safe’ but fails to prevent his death. The lawman works to save a dying social order, but fails to make the forces that threaten it ‘hold still’.

‘Will you hold still, please?’

In her reading of No Country for Old Men Stacy Peebles uncovers an underlying value system opposed to the ethos of masculine power and mastery that the main characters represent, suggesting as alternatives renunciation and surrender to forces beyond individual control. The voice that speaks most directly to this alternative model of masculinity is given to a minor character, Uncle Ellis (Barry Corbin), who shares some hard-won wisdom with his nephew Sheriff Bell. When the aging sheriff expresses feelings of self-doubt and fears about his inability ‘to stop what’s comin’’, Ellis reassures him: ‘You can’t stop what’s comin’. It ain’t all waitin’ for you. That’s vanity.’ He implies that Bell should not assume personal responsibility for protecting ‘his people’ from a criminal element that has outmatched him. There are forces in this world, Ellis seems to say, that cannot be controlled by force. To think otherwise is vain, and dangerous. Likewise, the past cannot be changed. Regrets about how we have lived our lives are useless and crippling. Uncle Ellis is a living illustration of his quietist philosophy. Wounded in the line of duty as a sheriff’s deputy, Ellis is confined to a wheelchair for life, but feels neither anger nor desire for revenge. As he reasons: ‘All the time you spend trying to get back what’s been took from you, more’s goin’ out the door. After a while you just have to get a tourniquet on it.’

Existential Uncertainty

Chigurh’s will to control is intensified by the sadistic pleasure he derives from tormenting the condemned. This is most evident in his pre-execution ritual where he poses a final agonising question: What meaning does your life have, now that it has brought you to this? Or in Chigurh’s precise formulation: ‘If the rule you followed led you to this, of what use was the rule?’ In McCarthy’s novel, just before he ends Wells’ life with a point-blank shotgun blast, Chigurh presses him to consider the meaning of his existence: ‘It calls past events into question. Don’t you think so?’ (2005: 175). Here Chigurh seems to espouse a philosophy of fatalism: the future is always already prefigured in the past and the past cannot be altered. When Chigurh executes Carla Jean (Kelly Macdonald), however, his logic is somewhat different. In her case, it is a matter of moral imperatives. Chigurh promised Moss that his wife would pay the price if he did not return the drug money. Now he has come to make good his promise. As he had in his encounter with the gas station owner, Chigurh offers Carla Jean a last-chance coin toss to decide her fate. She refuses, compelling Chigurh to take responsibility for his actions, saying ‘The coin didn’t have no say. It was just you,’ to which Chigurh replies coolly: ‘I got here the same way the coin did.’ McCarthy elaborates Chigurh’s enigmatic reasoning, explicating more fully his philosophy of fatalism, when in the novel he explains to Carla Jean, ‘I had no say in the matter. Every moment in your life is a turning and every one a choosing. Somewhere you made a choice. All followed to this. The accounting is scrupulous. The shape is drawn. No line can be erased.’ ‘The shape of your path,’ he concludes, ‘was visible from the beginning’ (2005: 259). It is only during these existential inquisitions that Chigurh shows any genuine interest, however perverse, in the life he is about to extinguish. These are the moments in which we see a glimmer of life behind his malicious smile. The ritual coin toss with which he invites unwilling participants to wager their lives is little more than an amusement to Chigurh, a game to impress on his victims that their lives are ruled by chance and nothing else.

Chigurh is fascinated with the uncertainty of the human condition, a fascination he shares with the Coen brothers who return to this theme frequently in their films, notably in The Man Who Wasn’t There, their existentialist rewriting of Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice, and in A Serious Man, where college physics professor Larry Gopnick teaches his students about Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle. Heisenberg’s theory also appears in The Man Who Wasn’t There, where, as we saw in the previous chapter, defense attorney Freddie Riedenschneider exploits it to prove the legal principle of ‘reasonable doubt’. Although the Uncertainty Principle is invoked in both these films, its thematic importance is undermined by an ironic humour that disguises its potential seriousness. In No Country for Old Men the Coens drop their mask of ironic detachment and for once, through McCarthy, give serious voice to the existentialists’ insistence that the only certainty in life is the rule of uncertainty. In McCarthy the Coens have found a writer of philosophical fiction akin to Albert Camus, whose novel The Stranger rendered an existentialist reading of Cain and, as we have seen, provided a model for the Coens’ rewriting of Cain in The Man Who Wasn’t There. In No Country for Old Men the philosophical implications of a world ruled by uncertainty are made palpable in the figure of Chigurh.

Bell’s encounter with Chigurh, whose inexplicable savagery defies comprehension by the moral standards Bell takes to be true, triggers an existential crisis. Faced with the incomprehensibility of Chigurh’s crimes, Bell lacks reliable categories for understanding him and thus effective strategies for combating him. Ultimately, the defeat handed him by Chigurh forces the sheriff to confront the meaninglessness and futility of his actions and indeed the meaninglessness of the world at large. Bell’s sense of failure shakes his belief in himself as a lawman, but also his belief in God, whom he believes has abandoned him. As he tells Uncle Ellis, ‘I always figured that when I got older, God would come into my life.’ After a pause, Bell admits, ‘He didn’t. And I don’t blame him.’ Bell’s crisis of religious faith is symptomatic of a larger existential crisis which, according to Camus, Bell can only resolve by learning to accept ‘a life without consolation’. The question is whether or not Bell can live a life ‘without appeal’ (Camus 1991: 60).

What Camus means is that we must learn to live not only without hope for salvation in an eternal afterlife promised by religion, but also without the belief in truth or absolute knowledge and certainty of any kind. For existentialist philosophers like Camus, the old truths or certainties based on metaphysical concepts had become unreliable. Thus, reasons Camus, we must learn to accommodate ourselves to what is, to that which exists in the immediate present, and bring nothing into our perceptions that we can not be certain about. And if nothing is certain, at least that is a certainty. Camus claims that the acceptance of the fundamental uncertainty of human existence produces a ‘lucid awareness’ he calls ‘the absurd’, entailing the recognition of life’s meaninglessness which then facilitates a ‘leap’ of consciousness that frees us from traditional metaphysical illusions of unity, meaning and purpose. Throughout the story there are signs that Bell is entering a lucid awareness of the absurd, for example, in his commentary on a newspaper article concerning a Californian couple who tortured and killed old folks for their social security income. It seems no one took notice of these crimes until an old man was spotted in their back yard wearing nothing but a dog collar. ‘You can’t make up such a thing as that,’ says Bell to Wendell. ‘I dare you to try.’ ‘But that’s what it took,’ Bell continues. ‘All that hollerin’ and diggin’ in the yard didn’t bring it.’ When Wendell starts to laugh, then apologises, Bell consoles him: ‘That’s okay. I laugh myself sometimes. There ain’t a whole lot else you can do.’ Bell’s wisdom is rooted in the existentialist notion that the conflict between the seriousness with which we live our lives and the ultimate meaninglessness of human existence renders all human endeavor futile, absurd, and therefore a joke. Laughter is all that remains. The colourful anecdote Bell tells Carla Jean about Charlie Walser and the ‘beef’ he tried and failed to kill has a vaguely parabolic message, its point being, as Bell explains, ‘that even in a contest between man and steer, the issue is uncertain’.

In the dark uncertainty of the new West there can be no happy ending, no triumph of good over evil, no resolution of the story’s philosophical questions. Moss, a sympathetic and potentially heroic figure, dies unceremoniously, while his antagonist makes good the promise to hold his wife ‘accountable’ for her husband’s arrogance. Later, Chigurh, the villain, survives a car crash that should have been fatal and manages to walk away. Bell is powerless to prevent any of this and ends the story in melancholy retirement, still anxious and confused about the social and moral decay that surrounds him. The darkness of this ending extends into the epilogue, in which Bell relates a cryptic dream of his father slipping into the night, leaving his son to find his way through a barren wilderness alone. In his final monologue, Bell recounts to his wife Loretta two dreams about his father, one in which he is supposed to meet his father in town to receive some money which he promptly loses, and a second, longer dream of a horseback journey with his father through a cold, dark night in desolate and unknown lands. His father, riding ahead, carries fire, which promises light and warmth in the frigid darkness. In the dream, says Bell, ‘I knew that he was goin’ on ahead and that he was fixin’ to make a fire somewhere out there in all that dark and all that cold and I knew that whenever I got there he would be there.’ The symbolism of the dual dream narrative suggests that Bell may feel he has squandered his father’s gift, the money symbolising the value of the life given to him by his father and what he has done with it, a question that troubles him deeply, now that he is retired and forced to contemplate the path he has taken through life.

The second, longer dream seems almost biblical in its parabolic tone and imagery. The images of Bell and his father riding on horseback through darkness and cold assume an archetypal quality, reinforced by the image of the ‘horn’ his father carries ‘the way people used to do’. This is a trope resonant with meanings: a primordial image of ancient fire as the means of survival for primitive ancestors, but also conceivably a religious symbol of the divine spark of human life and the eternal soul as it journeys toward reunion with the heavenly Father. Perhaps, in relation to the imminent apocalypse imagined by Sheriff Bell, the fire in the horn is closer in meaning to the image of fire in McCarthy’s post-apocalyptic novel The Road (2006), which tells the story of a father and son struggling to survive in a world gone mad. The father tells his son that they are ‘the good guys’ who ‘carry the fire’; that is, those who guard and preserve the small remainder of man’s dwindling humanity in a world of inhuman savagery. In his dream Bell is left out in the cold, following after the father, who passes by, head down, as if in his passing unaware of the son’s existence. The horn of fire has not been handed down to the son who still wanders in the darkness seeking the light of the father. Bell has lost his connection with the ancestral patriarchal order he had hoped to conserve and ‘carry on’ and now must acknowledge his failure to do so. We are left with the sense that Bell is losing his belief in an afterlife where he would be reunited with his father, joining him in the light and safety of his fire, finally satisfying the all-too-human ‘nostalgia for unity’ described by Camus as ‘that appetite for the absolute that illustrates the essential human impulse of the human drama’ (1991: 17). Bell’s final words – ‘And then I woke up’ – are perhaps a call for ‘lucidity’, for an awakening to and acceptance of man’s absurdity in a universe indifferent to his existence, a call to ‘live life without appeal’.

No Country for Old Men ends on a dark note, leaving the meaning of Bell’s dreams uncertain – an ending perfectly consistent with the absence of narrative and interpretive closure in all Coen movies. At the end of the film the viewer is left in darkness too, left to puzzle the meaning of a story that even its narrator fails to understand, proving nothing, except perhaps that uncertainty is the only ‘principle’ the filmmakers themselves might trust.