James Boswell: “Then, Sir, what is poetry?”

Samuel Johnson: “Why, Sir, it is much easier to say what it is not.

We all know what light is, but it is not easy to tell what it is.”

IN 1961, I BOARDED a Holland America Line passenger ship and set sail for England. I’m amazed, now, to realize it was cheaper then to spend a week at sea than to fly. I was heading for a year at the University of Edinburgh—and Edinburgh did not disappoint me. The October winds scoured the soot-covered alleys and stirred up the dust of centuries. Boswell’s ghost walked the streets on rainy nights, Scots to the hilt with his fierce ambitions, and the cobbles threw back the sheen as he set out to discover—in Johnson’s life—an answer to his prudent questions. In the waning light of mid-afternoon, I found it appropriate to imagine him whispering past the doorways of churches and pubs, filled with a sense of what he could not find the words for.

Go to any source and you will find controversy about Boswell’s famous biography, The Life of Samuel Johnson. You will read that Boswell was too young, that he shortchanged the early years (or the later years), was obsequious, was devious, altered quotes, shaved the truth. But it’s Boswell’s Johnson whom we know, Boswell’s Johnson who probes the very heart of literature, and when he suggests the elusive nature of the poem—its refusal to define itself—we find ourselves nodding in agreement. Taking my cue from him, I ask myself what I would say poetry is not:

Not politics, no matter how “political” it ultimately is.

Not theology, despite the fact that it aspires to the spiritual.

Not narrative, though it often rides on a sea of story.

Not beautiful sounds, for they can be deceptive.

Not sheer cadence, for Hitler’s army marched to music.

Not beautiful thoughts, because they are often facile.

Not merely exotic, for that will soon pall.

Not easy pronouncement, which can be misguided.

Not sheer desire to change the world, even if some poems have done so.

Not what is known, but something that asks questions.

Ah . . . at last, a turning toward a definition, though if I question how poetry asks a question I find myself with multiple variations on the theme. And who, I end up interrogating myself, is doing the asking—the poet or the poem? And then I get caught up in the problem of how we can tell the dancer from the dance, and . . . well . . . you can see how this will end if I don’t extricate myself. So I turn to others for help. Poets have “defined” poetry for centuries, and much of the litany is familiar:

Poetry . . . takes its origins from emotion recollected in tranquility.

William Wordsworth

Poetry: the best words in the best order.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry.

Emily Dickinson

Poetry is what gets lost in translation.

Robert Frost

Poetry is the art of creating imaginary gardens with real toads.

Marianne Moore

Poetry is not a turning loose of emotion, but an escape from emotion; it is not the expression of personality, but an escape from personality.

T. S. Eliot

These definitions, though, further attest to the difficulty of pinning down poetry’s specific hold on us. They are sometimes abstract, sometimes fanciful—either all image or all idea. They strike me as being accurate without being practical. I still need something I can use.

This past summer, I was sitting in a large audience listening to two poets read their work. The introductions were enthusiastic; the poets dressed the part, but the work did not. Instead of poetry, I heard “stories.” The stories were mildly interesting, but they never rose beyond their narratives. Since the poets already knew the outcome, the stories seemed to complete themselves ahead of time, and sometimes they did not even live up to the “story” the poets told of the poems’ inceptions. Honestly, they were all prose. So, add this to the “not” list: not merely prose broken into lines.

If it doesn’t work horizontally as prose . . .

it

probably

won’t

work

any

better

vertically

pretending

to

be

poetry.

—Robert Brault1

Never mind that if I could see the work on the page, the lines might break in interesting ways. The poems might even have some internal rhymes, might even bear the whiff of something metrical. I’m sure some of them had something we might call “poetic.” (Certainly other people in the audience seemed to think so.) But they were not poems. They produced no emotions; no toads appeared; my head stayed implacably intact.

Afterwards, when others were gushing around me, I found myself at a loss for words. What do you say when you’re expected to praise, and you simply can’t bring yourself to do so? I opt for comments on delivery, or the one poem that left me with a question, or a line that seemed to me particularly engaging. In other words, by default, I comment on what is not there. Does this make me sound like the curmudgeon I feel myself to be at such a time? Partly. But it also makes me the critic I have become over the past quarter century. It makes me the reader in search of something subtle, even magical.

Here’s all I know:

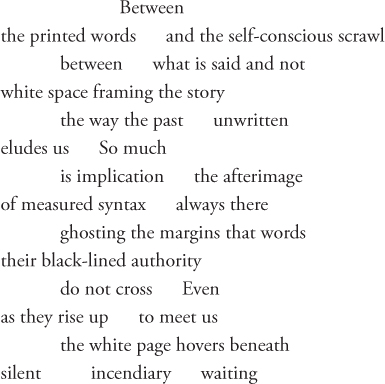

A poem completes itself in the reader. It does not know what it knows until the reader senses its presence. It has no agenda. It is full of wonder—and wondering. It listens for its own music. It complicates itself. It simplifies itself. It understands that it does not understand. It accepts the ineffable. It loves white space, wallowing in what is not said, what cannot be said, what will not be said. It says everything. It speaks across time, and space, and difference, and indifference. It insists itself. It insinuates itself.

And there I am, as abstract as anyone else, making my own generalizations. These characteristics define how poetry works on us. But still, they give no sense of how the poet works this magic, how the poem can be recognized. Which means, I guess, that what other people at that large reading identified as poetry might—maybe—have to be called poetry. I have to acknowledge that each reader comes with his or her own definition, his or her own taste, his or her individual requirements. But that would imply that I am comfortable with the idea that poetry can be whatever the reader claims for it—and I do not believe that, not for one second. As Whitman reminded us, “To have great poets there must be great audiences too.”

Thus I am back where I started, weighing the poem against my personal inclinations. Measuring and judging by standards I’ve developed over years. So now I realize that Johnson’s somewhat parsimonious outlook compels me to try to say a bit more than what poetry is not. Compels me to make an effort to describe the unbearable lightness of its being. To do so, I’ll look at several contemporary collections, considering not only the whole, but also the individual poems for what they bring to the table. I won’t be able to spend much time on the lines—the assonance or consonance or meters—but I will look at how the poem resounds, and I’ll try to cover a wide range of styles, techniques, and—dare I say it?—intentions.

Where better to begin this exploration than with our new poet laureate, Natasha Trethewey? Her latest book, Thrall, expands her ongoing focus on what it has meant historically to be of mixed race. Looking at ancient myths, Mexican casta paintings (along with the precise nomenclature listed in the Book of Castas), medical histories, etc., Trethewey shifts perspectives, sometimes moving close by taking on the persona of one figure in a painting, sometimes using the tool of distance to examine multiple points of view. But always the material is infused with personal experience: white father, black mother. As in her acclaimed second book, Bellocq’s Ophelia (2002), the angle of vision by which Trethewey looks at art or history has been influenced by her own struggle with identity, and this gives the poetry its distinctive charge—its incentive, if you will.

In Thrall, Trethewey sheds all masks as she moves seamlessly from her interpretations of history to her own experiences and back again—thus re-envisioning history through the lens of the present. For example, “Miracle of the Black Leg” looks at several pictorial representations of the mythic transplantation of a leg by Saints Cosmas and Damian. Each of its four sections explores a different perspective, and the final lines of the poem fuse them in one overarching question:

How not to see it—

the men bound one to the other, symbiotic—

one man rendered expendable, the other worthy

of this sacrifice? In version after version, even

when the Ethiopian isn’t there, the leg is a stand-in,

a black modifier against the white body,

a piece cut off—as in the origin of the word comma:

caesura in a story that’s still being written.

Trethewey’s poems force you to think, and to question. Is it true that, in Western society, we accept the sacrifice without thinking? There’s certainly a tendency to say that this has been the norm—and yet we also know that, throughout history, there have been individuals who have called accepted practice into question. Thrall reminds us that the work is unfinished: the fact that history is being assessed even as it is still being forged is everywhere in this book. Aware that race is still at least partly a determinant in one’s fate, Trethewey looks to her own life for ways that she has learned to look at the world. Never once does she embrace the role of “victim,” but at the same time she does not avoid naming realities. If we are to take these poems on their own terms, her father mirrored the scientists dissecting a drowned woman in a charcoal sketch as he studied his “crossbreed” child, and her careful rendering of the black mothers in the various paintings is occasioned by her sense that her own mother was often the forgotten figure in the photograph. In “Kitchen Maid with Supper at Emmaus; or, The Mulata,” the maid in the 1619 painting by Diego Velázquez is a stand-in for the poet four centuries later: “Listening, she leans / into what she knows. Light falls on half her face.”

Natasha Trethewey leans with nuance into what she knows, exhibiting a delicate ear, a precision of language, a meticulous sense of craft—all in service of a subject that is complex, and inescapable. History haunts the pages of Thrall, trapping alternatives in its net. The poet’s main focus is on the parents in the examined paintings—white fathers who dominate the canvas, black mothers who recede into “flat outline.” Race trumps gender in these renditions; still, the reader can’t help but wonder if, in today’s society, divisions may begin to crop up along gender lines. In “Enlightenment,” Trethewey’s portrait of Jefferson is fraught with ambiguity: how “white” his mistress might have been to make her “worthy / of Jefferson’s attentions,” how to interpret her father’s not-quite-suppressed attitudes.

Imagine stepping back into the past

our guide tells us then—and I can’t resist

whispering to my father: This is where

we split up. I’ll head around to the back.

His laughter at her joke becomes the fulcrum on which the poet can find comfort in “this history / that links us—white father, black daughter—/ even as it renders us other to each other.” In naming herself “black daughter,” she identifies with the tradition where “one drop” of blood is a stain, tainting the person in ways that can persist through generations.

Even the annotations Trethewey discovered in a secondhand book give rise to Thrall’s pivotal dualities. “Illumination” ends the collection, and its ending is provocative:

Poetry is an orphan of silence. The words never quite equal the experience behind them.

Charles Simic

In “Illumination,” there are no punctuation marks to bring closure. Silence reigns. Meanings, neither black nor white, are lost in ghostlike implications; everything that is unsaid and unwritten waits for words that might equal the experience behind them. Waits for a poetry equal to the magnitude of the issue.

My assessment could stop at this point—deducing that, for the poet, poetry has not yet found that moment—were it not for the opening poem of the book. Remembering a day when she was fishing with her father, the narrator finds herself trying to mine the event in order to “fix” the moment for an eventual elegy she plans to write. “Elegy” is that rare poem that helps define poetry simply by honoring the metaphor that rises to the surface. The poet’s job, then, is to get out of the way of metaphor, to make room for its subtle revelation. Understanding that she—the daughter of a poet—was self-consciously framing the present, Trethewey abandons an anticipated future in favor of what the moment actually evokes:

What does it matter

if I tell you I learned to be? You kept casting

your line, and when it did not come back

empty, it was tangled with mine. Some nights,

dreaming, I step again into the small boat

that carried us out and watch the bank receding—

my back to where I know we are headed.

Like a piece of ice on a hot stove the poem must ride on its own melting.

Robert Frost

“Elegy” is a perfect example of Frost’s melting. The careful couplets fuse father and daughter, locked (before the fact) in the book’s complicating issues, and locked as well in a series of near rhymes that underscore their differences. Intended to act as a foreshadowing, the poem begins as though it is sure of its “politics,” but ends in the wisdom of uncertainty. Memory speaks its own predictive language as the poem, freed of its restraints, finds its source of heat. The poet reclaims her personal past by watching the bank instead of the river. The poem becomes an elegy for the moment of its central discovery—that emotion is to be recollected, not invented. The arc of the “invisible line” that sliced “the sky between us” remains hidden, even as the speaker knows the eventual death of the father will spawn a genuine elegy.

All the poems that follow hark back to the core insight that, even though we know where we’re headed, we do not know what we’ll find there. The weight of that insight—its unanticipated significance—helps define what poetry can do: it can conjugate the verb to be.

On 21 August 2012, newspapers reported that radioactive leaks had recently been discovered in a double-wall storage tank at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation in eastern Washington. A second leak was confirmed on 31 August. The leaks, found at the site of what was already the nation’s costliest environmental cleanup project, further threaten at least 300 miles of the Columbia River as nuclear waste that will last thousands of years makes its way through the water table. This disclosure makes Kathleen Flenniken’s Plume, published earlier in 2012, all the more relevant. Currently poet laureate of the state of Washington, Flenniken grew up in Richland, close by Hanford and a place where her father boarded a bus each morning and “disappeared to fuel the bomb.” Many years after working there as a scientist herself, she began the research that resulted in the convergence of her own story with those of others, especially the father of her childhood friend who died of radiation exposure.

Plume examines the mindset of the Cold War, probes the growing doubts of scientists, and worries away at the “art” of censorship. The poems, for all their weight, do not impose a political stance so much as they explore a range of perspectives. No one style or point of view could contain the complexity of Flenniken’s subject, and she employs an impressive array of personal lyrics, persona poems, songs, and fragments—along with “found” poems from documents and reports—to consider the origins and scope of this particular environmental disaster. The questioning mode leads the poet to imagine the lives of others—prominent scientists, workers, survivors—and consequently she grants herself sufficient latitude to investigate fully not only the government’s subsequent indifference (and even cover-up), but the limits of scientific knowledge as well. For the most part, the poet reproduces the innocence of childhood, only allowing her present knowledge to intrude as subtle irony or self-interrogation. Thus she effectively reproduces the flavor of the times: the isolation of the landscape, the naïveté of the workers, the foreboding sense of external threat, the unswerving patriotism, the imminent potential. Yet a mature sensibility hovers over the whole, providing a retrospective angle: “This is the future. // Dad holds me up to see it coming.”

A poem is true if it hangs together. Information points to something else.

A poem points to nothing but itself.

E. M. Forster

Luckily for us, these poems are not merely information. The “Notes” section at the back of the book reveals the shameful facts, but the poems are restrained, incorporating those facts in ways that convey a collective innocence and a budding apprehension. Flenniken amplifies her vision by using (or breaking away from) formal structures. Consider the careful tercets of “The Cold War” as it tumbles down the page, through bomb shelters and H-bombs and Khrushchev’s shoes, to its ending:

I remember the red phone, and missile codes,

how every movie hinged

on a clock ticking down.

We called it the arms race

and there were two sides.

It was simple.

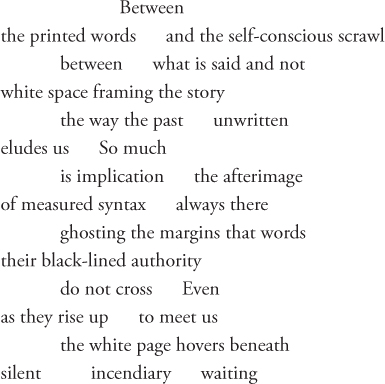

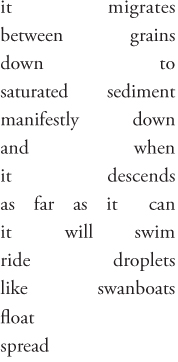

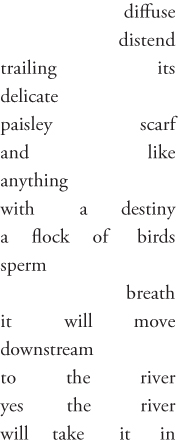

Or watch language itself break apart in the spare columns of the title poem:

“Plume” slows the flow of words until they, too, “unfurl” and “fan” and “feather” and seep through permeable soil until the conclusion seems inevitable. This is not L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poetry, but poetry that demonstrates the fluidity of language, taking meaning “as far as it can” as it moves downstream.

The lines in the two stanzas of “Afternoon’s Wide Horizon” reverse themselves so that, technically, the poem reads the same forward and backward, but punctuation intrudes to shift the meanings of the lines in subtle ways. The couplets of “Bedroom Community” end with mild half-rhymes that keep the ear alert even as they disrupt any sense of certainty. Three separate poems, each titled “Redaction,” force us to turn the book on its side to experience the effects of censorship. They begin with typescript from pamphlets, articles, and speeches of the times, then reproduce the typewritten quotes with huge sections blacked out, leaving only a few words and letters available. The second of these redactions quotes J. Robert Oppenheimer from 1947; it begins with “The whole point of science is . . . to invite the detection of error and to welcome it” and goes on to implore open examination of what was happening at the Hanford site. Through Flenniken’s careful choice of which letters and words to leave intact, the censored version reads “science vetted in ignorance may incite chaos.” The reader is compelled to read the documented assertion, the redacted version, and their juxtaposition as one complete experience; the resulting insight can be seen to apply to many contemporary issues.

Out of the quarrel with others we make rhetoric; out of the quarrel with ourselves we make poetry.

W. B. Yeats

Plume does make its quarrel with others, but it is also full of self-doubt. “Museum of Doubt,” addressed to an unknown “you,” demands that we look at photos of Nagasaki—the shadows that are like “interrupted sundials”—but the “you” at its ending seems, somehow, to have merged with the speaker:

Meaning is lost

between the vulnerable eye

and well-defended mind.

Who’s on your side (you keep asking)?

Not righteousness, not at this late hour?

Look at you, unsure

but sure underneath.

The quarrel is never more pronounced than in “Museum of a Lost America,” where the country the speaker was taught to love (its cardinal directions: “orchard in bloom; / crickets at dark; / wheat up to the ridge; / fence line in snow”) has betrayed her. And yet she loves it still—

Oh Beautiful,

I will not stop.

—and adds it to her “losses.”

“Going Down,” one of my favorite poems in the collection, begins its stanzas with a nursery-rhyme echo of “This is the house that Jack built” (“This is the guy in the white fastback Mustang . . . This is the woman with wooly blond hair . . . These are the thousands who rise before dawn . . . This is a pattern of acting out”) to evoke the sameness of the mornings—the Mondays or Tuesdays or Wednesdays—as the hundreds of workers head off for the site. There’s humor here, but a humor that utilizes metaphor as it turns serious by the final stanza:

This is the landscape bleak and brown

that can hold its secrets for only so long

till they spill and spill, but for now and instead

the woman goes down on the man driving fast,

we cop our looks while they rocket past

and the rest of us feel . . . not closer to death, but further

from life as we slow at the gate for security check

on another Wednesday morning.

The University of Washington Press has done a beautiful job with the production of this book: the space between lines makes for easy readability; the poems fit perfectly on the page, providing a visual sense of their methodology; and the elegant austerity of the design gives dignity to its subject. The overall effect is one of elegy—and urgency. Flenniken would like us to recognize what the future could hold. And still she loves the place itself. This might best be shown in the words she has put in the mouth of John A. Wheeler in “A Great Physicist Recalls the Manhattan Project”: “Think of it—a desert in Washington State. Along the icy blue Columbia. . . . As for whether // I solved the poisoning riddle, let no man be his own judge. . . . I think of that place as a song not properly sung.” In Plume, Kathleen Flenniken reminds us that a central definition for poetry is song, properly sung.

Discovering a previously unfamiliar voice can be exciting, and several presses now perform an important service by bringing back work that may have been missed the first time around. Published by Bluestem Press in 1993 and out of print since 1994, John Hodgen’s first book has recently been reissued in paperback by Lynx House Press. Like Trethewey’s collection, In My Father’s House opens with an elegy of sorts, and the loss of the parent quietly dominates the rest of the collection. “For Mr. Grimes Who Tried to Teach Me Physics after My Dad Died” makes the father loom large by relegating him to the title alone. The vocabulary and principles of physics become the language in which the adolescent begins to accept death:

He spoke of ellipses,

of things coming round again.

He spoke of resistance,

of the forces that act upon us.

He spoke of gravity,

of the earth that draws us to itself.

He said the mass of the earth,

the changes of state.

He said that a body at rest

would remain at rest.

He said that a boy

standing at the end of a moving train

could toss the red ball of his life

up into the heavy air

and catch it again.

If you know what you are going to write when you’re writing a poem, it’s going to be average.

Derek Walcott

Hodgen’s opening poem alerts the reader to the collection’s underlying themes. Time and time again, the poet addresses untimely deaths—whether it be his cousin dying of AIDS or a stranger whose death is reported in the newspaper. Titles such as “For the Woman Whose Husband Fell Seven Stories to His Death Trying to Get in the Window of Their Locked Apartment,” “For the Faceless Boy,” and “Boy Struck by Lightning Survives” function almost as headlines, and the reader expects the story to follow. But Hodgen avoids the “average” because he almost always ends up surprising himself as well as the reader. The poems veer off in interesting directions. For example, here’s what the boy struck by lightning sees:

Slender lines alive in the light,

the swirl of magician’s wands,

the dance macabre in the veins

of an old woman’s legs,

chiaroscuros of the blind,

eyesockets of snakes,

spun gyros, filaments,

the wrinkled skin of the air,

every jot and tittle,

the blue and red whirlygigs

pulsing on the walls of the placenta.

Some go intensely internal, as in “For One Whose Daughter Is Gone, and for Others”:

If this were Solomon’s world, all cut and halved,

I, two-daughtered, would offer him one,

or, if daughters were blossoms, I would harrow bouquets,

turn vendor for nothing at intersections, corner lots,

daughters curling like vines about my rusted van.

To imagine the lives of others is to reconnect with your own. Hodgen demonstrates how poetry so often is the fusion of two separate concerns, each one informing the other. He weaves fleeting references to his own losses throughout, and as he lightly touches down the reader experiences these events as almost tangential, part of the larger collective story—the “many mansions” that blaze in the daily headlines. As if to underscore the poet’s desire to invent new variations on old themes, one pair of poems even looks at the same event from slightly different perspectives. “Flying Out of Charlottesville Fog on All Hallows Day” has as its focus the fog, the tedious wait, the final takeoff, and, from above, the sudden sight of a burning house. “Flying Out of Charlottesville and Seeing from the Air a House Engulfed in Flames: Variation” begins with the spectacle of the fire and moves to the passengers’ helplessness, which leads to a contemplation of the nature of God:

Perhaps He sits there now like a handcuffed juggler,

like one Hardy boy,

waiting for the Buick Dynaflow to come streaming, slowly,

around the corner of the world, His father getting out,

after driving all the way around Robin Hood’s barn,

and now, with the help of the silent farmer next door,

rolling the stone away.

Since this is neither the first nor the last reference to the Buick, we realize how quickly Hodgen can personalize a situation, how readily his own father rises up to provide metaphor. By the final lines of the poem, Hodgen has extended his list of possible deities, and specific circumstances, to include his present situation, with all its shared vulnerability:

Or those rows of TVs in Sears, and He the tired salesman,

always wandering off, now in household, now in hardware.

Or all the windows in an airplane when it breaks into the light,

each one a little home, like the windows in a school bus,

a face in each one, shining.

Everything one invents is true, you may be perfectly sure of that. Poetry is as precise as geometry.

Gustave Flaubert

Hodgen’s geometry is meticulous. The poems of In My Father’s House are full of details that seem, like that TV salesman, to be pulled from the poet’s prolific imagination. Invention is necessity; the reader recognizes his method as a way to “read” the world—not measuring one thing against another so much as taking the measure of everything. Just below the surface of every poem is the suggestion that the poet understands the limits of human speech to make logic of the irrational:

The words stand around unemployed in my throat, like shirts, frozen

left out on a line, or dogs in a yard, the family gone away.

I am the quick brown fox’s lazy dog. I lift my head.

I look the other way.

And what can be said in the face of death? What is it that pilots say most before they crash?

Oh shit, we say, as if we’ve always been in it,

this ground, this stink, this awful place,

the earth coming up at us like the right hand of God,

us seeing it coming. Oh shit, we say, oh shit, oh shit, oh shit.

For a poet, another form of invention is craft—the constant reworking to fit the syllables to the cadence of one’s inner music, or the absorbed attention to sound or pattern, the echo of tradition even as the poem strives for eccentricity. So it is too bad that Lynx House did not do a better job of copyediting; often words or lines are run together, words are broken up, or lines don’t break as they were clearly meant to. These problems stem from careless digital formatting, and they are understandable but inexcusable. For example, “bedroll” becomes “be / droll.” There are enough of these instances to cast doubt on the lineation—and therefore on the perceptible rhythms. But there is no doubt that there is craft to be found; note how “For Grace and a Print by Bernand Khnoppf” fuses memory and art in a complex of unexpected rhyme (abacdecfe dabafegg) that pulls one stanza inextricably into the other. Via Hodgen’s reversal of sound, as well as of the flow of time, the issue of whether the artist dreamed the future is transformed into the poet’s resurrected past:

Here in the brown and gray of this print, this face,

as surely as I once believed there lived somewhere

my twin, my lonely double, is my aunt, weary Grace,

wide-jawed, glad-eyed, too ready, always, for death.

She lay in a rosy bier in Dorchester in 1955

while her ham-fisted husband who beat her by day

and who called me Palooka, always, in his beery breath,

coughed till he shook in the stains of his shirt

and cried, punch drunk, when they took her away.

Did he dream her, Bernand Khnoppf, in Germany, 1905,

the way we make the canyoned moon our father’s face,

form safe heaven out of flimsy clouds and air?

Did you walk before us in a pre-war place,

lending beauty for nothing against the future’s hurt,

holding a glass up, lovely, to the trembling day?

Or do you live again, if only for an hour,

here, now, brown eyes, blue flower?

I would be tempted to caution the poet that the inventive can sometimes become a crutch, but then I remember that this is a first book from two decades ago, and I suspect that by now the poet must have already learned this lesson. The poems of In My Father’s House have a young man’s compulsive sense of morality—that things must be made right. They question God, even as they acknowledge Him. This fierce impulse seemingly still prevails, because during an interview in 2010 Hodgen said the following:

Every poem has its own prism of morality, a single voice registering its sense of what is just and valuable. One of the reader’s tasks is to sound out that voice, to align with or against it. If the poem isn’t about something right or wrong, if it doesn’t try to help or heal in some way, even in its anguish, humor, irony, or even rage, it doesn’t really ever fully become a poem.

—interview with Brian Brodeur on “How a Poem Happens”2

I’m not sure I agree that poems should help or heal, or even that we would recognize when they do, but at least John Hodgen adds to the ongoing discussion—and I look forward to new humor, irony, even anguish and rage, from this poet with whose work I have just recently become acquainted.

Alice Derry uses musical terms as titles for the five sections of her fourth full collection, Tremolo. These terms, along with their definitions, help to orchestrate and shape the emotions that fuel this book. Derry moves easily in and out of history, pondering the presence of the Quilleute Indians of her native Northwest as her family camps or walks along the Pacific. She also looks at the forces at work on individuals as she delves into the bombing of Dresden as well as the cost of the Holocaust, the documented diary of Anne Frank and the imagined time when a young woman overheard her husband planning a new Nazi sweep and warned her doctor to leave—that night. Recognizing the personal in the political, Derry extends her equations to encompass contemporary events, characteristically interweaving family stories (her mother’s death, her father’s dementia, her daughter’s upcoming departure from home) with those of others around the world. These are narrative poems, simply told—but music is their scaffolding, and Derry’s stories are almost always accompanied by the grace notes of the past.

These poems have no “speaker” other than Derry herself; she owns them from the outset, using the words “I” and “my” in several titles, inserting such descriptive phrases as talking to my daughter and on our visit to Europe, 2007 between title and text—and thus ensuring, by specifics of time and place, that the experience recounted is solely hers. “Deposition,” one of my favorites, is preceded by an admonition that the natural process of building narrative will not be adequate: It’s not a storytelling process, my attorney reminds me. Under questioning, nothing is quite what it seems: “The knowledge rises in me / I have lost my side / of what happened forever.” “Deposition” comes early in the book, and all the poems that follow seem to struggle with the sense that words will not suffice.

“What My Student Discovers” recounts a conversation after the student has visited a cemetery in Austria that contains graves embellished with swastikas along with a memorial to the Holocaust. Two histories are contained in one small plot of ground to which the bodies of the soldiers had been sent home for burial. The final stanza reveals a growing comprehension by student and teacher, and offers the same to the reader as well:

The living soldiers struggled on

toward Stalingrad, leaving behind them—

in ditches they covered over

after they had done the shooting

and the bodies had tumbled in—

the Jews of Russia.

Derry’s poems do not rely on chronology to tell their story, but on juxtapositions that allow things to collide and activate emotion. So it is, for example, that her daughter can one moment be a young woman and the next a child in school. In “On the Radio, Mozart’s Piano Trio #7 in G Major,” the poet finds herself sitting in stalled traffic listening to notes that seem like beads on a necklace; she slips into a reverie that ticks off the Twin Towers, an earthquake, a bomb at Passover Seder, child abuse—until she shakes herself into the present: “And still Mozart’s notes pass over your tight-stretched / eardrum, sound wave after wave translated to vibration.” The poem could end there, but it doesn’t. The poet knows she cannot shake the “scalding necklace,” knows that that suffering has inserted itself into her sheltered life. Still, there’s that music . . . and later, “Through the open window, frogs’ bright insistent chorus / announces the complications of hope.” The poem could end there, but it doesn’t. The emotions are far too complex—for how does one weigh beauty against atrocity? Therefore it ends with Shakespeare’s Desdemona singing, and the gesture is not so much resolution as recognition:

The notes of the song flood the night

no less than dread.

Poetry is Emotion put into measure.

Thomas Hardy

In the case of Tremolo, the measures are syncopated. Derry does not give us meter so much as the vestiges of meter, yet the combinations of vowels and consonants, along with the mixture of rising and falling rhythms, make them eminently “singable.” But never singsong. The first stanza of “I Mean Beach, Fir, Yellow” describes a hike, but the description also illustrates her working method:

A ridge isn’t what you’d think,

level on top while all the struggle

falls to either side. It’s a steady rise

and fall and rise through fir and pine,

then meadows, then up into the scree,

the last steep scramble for the view.

Husband, wife, daughter—the family’s camping trip is fraught with understated emotion. This is no idyll. Tension seems to fill the air. If the speaker looks closely, flowers become yellow stars that “burn / their little wells of growing space / into the melting snow”; her too-tight boots become “boots marching across a continent.” Everything is seen in terms of something else. “All I have now is my own story.” She piles up words and scenes, but there is no song for refugees who unravel image after image of what has been lost: “words bring back the ache / without the things themselves.”

Poetry provides the one permissible way of saying one thing and meaning another.

Robert Frost

Derry’s poems do not say one thing and mean another so much as they mean both things at once. She is not as deliberate as Frost, possibly because she is not so sure of what she means. Always probing, she proceeds through seemingly spontaneous association to blend threads of narrative in such a way that they play with—and against—each other. Aware of the various alternative paths inherent in any one moment, Derry looks at the forces of history as they lead up to and away from events that impinge on ordinary lives. At times she gives just a tiny bit too much exposition; some of her final lines or sentences could be omitted, allowing the poems to end with less resolution, and thereby compelling us to follow them out into the world, or to look inward, interrogating the self.

Derry, who has been a teacher of German as well as writing, uses the German language (its “tight syntax”) as a portal through which she examines warring emotions. Weaving both the words and their translations throughout, she gives voice to many points of view. The word raps (rape)—with its English connotations—takes an innocent crop and turns it into a killing field, and the “beech forest” that is Buchenwald provokes its own disturbing commentary:

A word can be tied by torment

to so many things opposite of tree and leaf,

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

is to break a certain kind of faith

with those who heard it as death.

In the end, Derry gives the two connotations equal measure, but her final stanza seems to opt for restoration:

Say Buchenwald. Without its sound,

we might forget this forest.

Trees don’t need to speak. We do.

Emotion suffuses these poems through understatement, implication, and allusion. That’s not to say they are offhand or casual. They are intense, but often the intensity is deflected so that its focus is elsewhere, letting the emotion quietly claim its place. Alice Derry shows us how to gain perspective. Staring at the paintings of Morris Graves, the poet sees through another’s eye and alleges she has entered “another dimension.” Still, she needs sound to clarify: the “unlikely tones” of his paint lift from the canvas and his bird flies; the snow outside her window is background to the thrush, whose “high clear solos / break into the cold, each bird, one note, / drawn out until it fades, as it has to.” Expression reveals its counterpart in wordless music, and we become attuned to what she is not saying. Meaning becomes implicit. The fifth section’s epigraph alerts us to what Derry is striving for as she digs deep, then deeper: “At that specific point [of music], emotion has staggered into inarticulacy beyond the boundaries of language . . .” —Brian Friel.

Tremolo is an act of discovery—no, not discovery so much as detection. It is as though the poet understands that if she sifts through the fragments of her own life, she will solve—or at least resolve—some of its many mysteries.

Genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood.

T. S. Eliot

Eliot’s statement is more complex than it first appears. I would contend that his assertion is more true for lyric than for narrative poetry; after all, a story has shape, needs to unfold to be understood, but the lyric—with its quality of interiority—only needs to convey its urgency in order to communicate. The reader instantly “understands” its psychology. This is certainly true for the poems of Lola Haskins’ newest collection, The Grace to Leave. Haskins trusts that her emotions will speak in their own language, and that, in time, we will discern both source and consequence.

The Grace to Leave is orchestrated in four sections, each of which moves fluidly within time. The effect is that of taking stock, in no particular order, of what it has meant to be daughter, wife, mother, grandmother; what it has meant to be single, married, divorced, single; what it has meant to know—and love—a place, a person, a way of being; what it means, in the present, to look back to the past; and what it means, in the present, to look to a future in which you will no longer exist. The book opens with a singular poem, “Seven Turtles,” where, while paddling on the Withlacoochee, the speaker notes first the “routine” turtles on a log, then wood storks “hunched like priests in a tree,” on her way to remembering a woman in Cairo who grasped her hand and said “in the only language / we both understood: Pass this on.” And that is what Haskins is doing—in short, lyrical bursts, she is passing on her idiosyncratic experience of the world, encapsulating the emotional highlights, the moments that matter in a life spent noticing.

The first section looks hard at the body. With titles like “Brows,” “The Considerations of My Teeth,” “Nostrils,” “Pavan for the Little Finger of the Right Hand,” “Ode to My Small Hair,” “The Great Toe,” “Knuckles,” “Footsoles,” etc., Haskins makes us alter our way of seeing; over and over the lines, or sentences, find a natural simile or metaphor—as in “Capillaries”:

I love that my body has many tributaries like these, fine as hairs lit

by oxygen.

and in “Moles”:

But these poems do not settle for mere figurative language. They move inevitably to images that enlarge the poem, force it into significance. “Of the True Ankle Joint” advances from the literal to the associative in three short segments. The final one reveals how rapidly Haskins can shift into implication:

Consider love, consider fine china:

One hairline, almost invisible, fracture,

and the tea will steep unstoppably into your hand.

A poet is a man who manages, in a lifetime of standing out in thunderstorms, to be struck by lightning five or six times.

Randall Jarrell

Suddenly the poems of this section pivot to the moors of England, and we find ourselves bodily walking the Roman road between Skipton and Addington in North Yorkshire. Flanked by blueberries, harebells, dock, gorse, the poet has to look down in order to see up, noting the clouds that “still swim in the standing water.” The final sentence speaks volumes: “How casually they let the centuries fall.” Time recedes; we have entered the silent eternity of nature.

At this point, lightning strikes. “The Ballad of Foot and Mouth” is one of those five or six poems a poet waits a lifetime to produce. How does this happen? Luck, confluence, insight, being in the right place at the right time, patience, recognition. In this case, Haskins was able to use ancient counting rhymes to accentuate the loss as local farmers were forced to incinerate their sheep to prevent the spread of the disease. Through the repetition of words and lines, even the present becomes a kind of rhyme, keeping time with the past in an ageless lament:

One-ery, Two-ery, Ziccary, Zeven

Hollow-bone, Crack-a-bone, Ten-or-eleven

Spin, Spun, It-must-be-done

So they push them up—the ewes,

the wethers, the lambs, the tupps—

With their yellow dozers like flowers o

and so on until, stanzas later, what is happening is internalized:

And what is motherhood now o

as the ash smoulders in the backs of our throats

of the ewes, the wethers, the half-grown lambs

And the moors all empty but for the wind

that moans as it licks at the dry stone walls

And that’s your motherhood now o

Spin, Spun, It-must-be-done

Twiddledum, Twaddledum, Twenty-one.

The wind moans. It knows nothing of loss, but the language of grief is universal.

And, if it is possible to be struck by lightning twice in quick succession, the next poem further memorializes place. “Moor” opens with a question: “And what survives? Only the voracious / gorse, with its dark green prickles . . .” and the heather, the bracken, each trying to choke the rest. This is a place where “no map, no piece of paper at all, no page from / the psalms, no verse from the Quran, not even James Joyce / can hold back the mist.” It is outside of religion, or literature. It is of itself. So the third part of the poem becomes an italicized, ecstatic “day spent staring”—which is as close as Haskins comes to defining how a poem comes into being. The poet emerges, in first person, with a kind of faith:

would not matter

. . . . . . . . .

I was not dying

but ascending another scale,

like the curlew for whom flight is not

enough but she must sing too.

“The Return” imagines a mother and son coming back to a cottage where they had once lived. Everything is in ruins, but the poem rebuilds field, walls, home as the speaker remembers the feel of her baby’s head under her hands, and the boy remembers his mother as a bird. These longer “moor poems” are so strong they tend to overpower the other poems, especially so early in the book. They probably deserve a section all their own. For an ideal sense of balance, they might be situated in the middle, and then the lyrics could revolve, like planets, around them.

The Grace to Leave is, essentially, a coming to terms. Sometimes the poems are infused with the questioning voice of the child, and sometimes they carry the wisdom of the sage, but always they speak with refreshing candor and with surprising combinatorial power. Haskins launches herself into the world, wanting to remove all barriers, “to lift away without touching, any cloth that lies between you and my skin.” The images worm their way inside; the voices take on various tenors; things are presented in terms of other things; generations fuse; time becomes fluid; the alchemy of ideas can appear to be almost surreal. The range and variety—from formal structures to prose poems to tangential meditations—show not only versatility in style and technique, but also a brand of generous receptivity.

Poetry and Hums aren’t things which you get, they’re things which get you. And all you can do is go where they can find you.

A. A. Milne, Winnie-the-Pooh

Haskins places herself firmly where poetry can find her, and she hums its various tunes in remarkable synchronicity with the world. At times, the poems approach the impressionistic, each brushstroke infused with a concentrated energy that suggests an equal force within the writer: “If only we could always live on the verge // of shivering, on the cliff-edge of too much.” But the mind knows better, understands that “what we must love instead is zero.” More than most contemporary poets, she has mastered the art of white space. Refusing to be haiku, “Enlightenment” is simply suggestive:

the fish suddenly

understands.

Lola Haskins understands that we all must learn how to relinquish what holds us. However, the closing poem exposes some crucial ambiguity. “The Sandhill Cranes” captures the ephemeral. Coupled with the title of the book, its final stanza is wonderfully contradictory:

The long bones of sandhill cranes

know their next pond. Not us.

When something is too beautiful,

we do not have the grace to leave.

I like to imagine Johnson and Boswell sitting in a coffee house. It’s raining, and they have come in to get warm. Their woolen coats steam before the fire, and in my fantasy they resume their former conversation:

Boswell: “But Sir, one cannot prove the negative. I’d like to know what poetry positively is.”

Johnson: “Perhaps I should reiterate, Sir, that it can’t be defined so much as experienced.”

I like to imagine their contemporary counterparts. It’s a beautiful autumn afternoon, but they have sequestered themselves in a dark corner, each alone at a table with his laptop open before him. Two men are looking for answers. They are not talking to each other, but are asking a question of someone out there, somewhere. They have forgotten that outside the leaves are burnished and clouds skid across the sky. They do not notice the clock on the wall, or the intricate design on their lattés, or even the coffee’s somewhat bitter taste, as each of them clicks on Google and types in the phrase “definition of poetry.” Silently, each begins to quarrel with what he finds. The definitions on their screens are clever, but they always stop short. They do not really take into account the flicker of doubt that lies at the heart of most good poems. Or the fleeting music of the mind as it makes inspired connections.

It’s a rainy winter morning and I have failed in my quest for a comprehensive definition. My friends seem to have deserted me, lost in their abstract—if original—characterizations. Outside my window, there is no sky—only a pervasive cloud cover the color of the sea. The pyrrhic drumming on the skylight taunts me with Hart Crane’s words: “And the rain continues on the roof / With such a sound of gently pitying laughter.” I laugh at myself. Maybe it would be easier to tell the poet from the elusive poem . . .

To be a poet is a condition, not a profession.

Robert Frost

The poet is the priest of the invisible.

Wallace Stevens

A poet must leave traces of his passage, not proof.

René Char