2

King Josiah: Purifying the Realm

The leaders of the Edwardian regimes set out to destroy one Church and build another. This is the most important continuity between the ascendancies of Seymour and Dudley. Yet the story contains a good deal of hesitation, and most of this hesitation is to be found during the time of the more demonstrative evangelical leader, Protector Somerset: the period 1547–9. Does this then indicate that the official Edwardian Reformation was a series of haphazard steps or that, particularly in its first phase, it reflected an ideology of moderation and compromise? To provide answers, we must consider how the old Church was pulled down. The whole process can be traced through a detailed consideration of Edward’s first regnal year (January to January 1547–8), which reveals a consistent strategy which went into creating King Josiah’s purified Church.

The Church of England inherited by the evangelical establishment around Lord Protector Somerset in 1547 reflected the old king’s eccentric mélange of religious opinions (here). In presenting religious policy over the next year, the new rulers sheltered behind Henry’s ghost: they claimed that his unstable theology had been about to change direction once more. When the imperial ambassador expressed his concern about what was happening to the English Church during the summer of 1547, Somerset and his devious adviser William Paget blandly told him that their policies were merely what Henry VIII had been planning just before his death.1 In the immortal phrase of Mandy Rice-Davies, they would say that, wouldn’t they – but there is enough evidence to give their claim some substance: detailed and circumstantial statements (made at much the same time) from Archbishop Cranmer and from the Strassburg reformer Martin Bucer that if Henry had lived, the mass and clerical celibacy would have gone.2

The most realistic assessment of Henry was nevertheless that of an evangelical outside government, John Hooper, writing to his admired friend the leader of the Zürich reformation, Heinrich Bullinger, just before the old king’s death. Hooper was speaking from the comparative safety of exile in Strassburg, where it was possible to be frank about England’s alarming monarch. Hooper pointed to the international situation and to the Schmalkaldic War in Germany, where the two religious parties of central Europe had finally squared up in a war inspired by ideology. He suggested that the outcome of the fighting between Charles V and the German Lutheran princes of the Schmalkaldic League would decide matters in England: ‘the king is adopting the gospel of Christ, if the emperor should be defeated in this most deadly war: should the gospel sustain disaster, then he will preserve his ungodly masses’.3

Hooper had rightly sensed the instability of Henry’s thinking. The king was facing increasingly polarized religious choices as he unravelled more and more of the old system. Deeply felt as his theology was, its radical incoherence – stranded between his loss of purgatory and his rejection of justification by faith – meant that he needed some external criterion for making theological choices: the criterion was likely to be the balance of diplomatic advantage for his kingdom in a divided Europe. By contrast, the clique around Somerset unhesitatingly adopted the more radical of Henry’s stark alternatives, and for all its hesitations, it would not thereafter be diverted for long by diplomatic embarrassments from moving towards its aim. Yet all the while the Edwardian evangelical establishment had the advantage of the ambiguity of Henry’s last years; it could keep opposition within bounds, as long as it could put out enough contrasting signals to reflect the old king’s diverse views.

The constraints both overseas and at home remained. The Emperor Charles V’s attitude to the new regime was very dangerous; he regarded the Lady Mary as the true heir of Henry VIII, and if Charles’s agents could have detected any groundswell of English support for putting her on the throne, the Empire might well have withheld recognition from Edward. Even when it quickly became clear that there was no internal challenge, England’s tense relations with France and eventual slide into war meant that Somerset could never ignore Charles’s feelings.4 Four years later in a review of policy, William Cecil was still suggesting a worst-case scenario in which a furious Emperor combined with English conservatives to bring down the regime.5 For at home, the evangelicals were considerably more nervous about public opinion than Henry had been after his flamboyant thirty-eight years on the throne. Archbishop Cranmer felt the need to justify to Ralph Morice, his trusted secretary, the slow pace of change in Edward’s first regnal year: ‘if the king’s father had set forth any thing for the reformation of abuses, who was he that durst gainsay it? Marry! we are now in doubt how men will take the change, or alteration of abuses, in the church.’6

Cranmer and his colleagues must cope with the uncomfortable reality that outside the court and the Council chamber, their chief support came from people who did not matter in politics: Cambridge dons, a minority of clergy and a swathe of people below the social level of the gentry, all concentrated in south-east England. The projected Edwardian Reformation could not expect enthusiastic support from the majority of lay people in positions of power, gentry and nobility. Likewise, few bishops would cooperate wholeheartedly with the dismantling of traditional religion; yet little could be done without them, and they had formidably aggressive spokesmen in Bishops Edmund Bonner of London and Stephen Gardiner of Winchester, third and fourth in the church’s hierarchy. One of the conservative bishops’ former colleagues, the doyen of evangelical preachers, Hugh Latimer, felt entitled to exploit his celebrity status by launching an open attack on them from the royal pulpit, with a plea for their forcible retirement: ‘make them quondams, all the pack of them’, he begged the king and Council in early 1549. However, the government could not afford such self-indulgence. Its major preoccupation in the Somerset years was to conciliate the bishops, particularly Gardiner, in order to get grudging consent to a step-by-step reformation.7 Intimidation or confrontation was only a last resort when consent was withheld.

Thus the regime felt the need to work around three hostile constituencies: the Emperor, the majority of the lay political nation and those bishops who were not part of the inner circle. Increasingly extrovert in general style, Somerset’s government habitually gave out two contradictory or alternative messages in religious matters. It was not so much moderate as schizophrenic in its religious pronouncements, seeking simultaneously to please its own circumscribed constituency of sympathizers while seeking to divert everyone else who mattered. It urged on evangelicals to destructiveness, and everyone else to peace and unity.

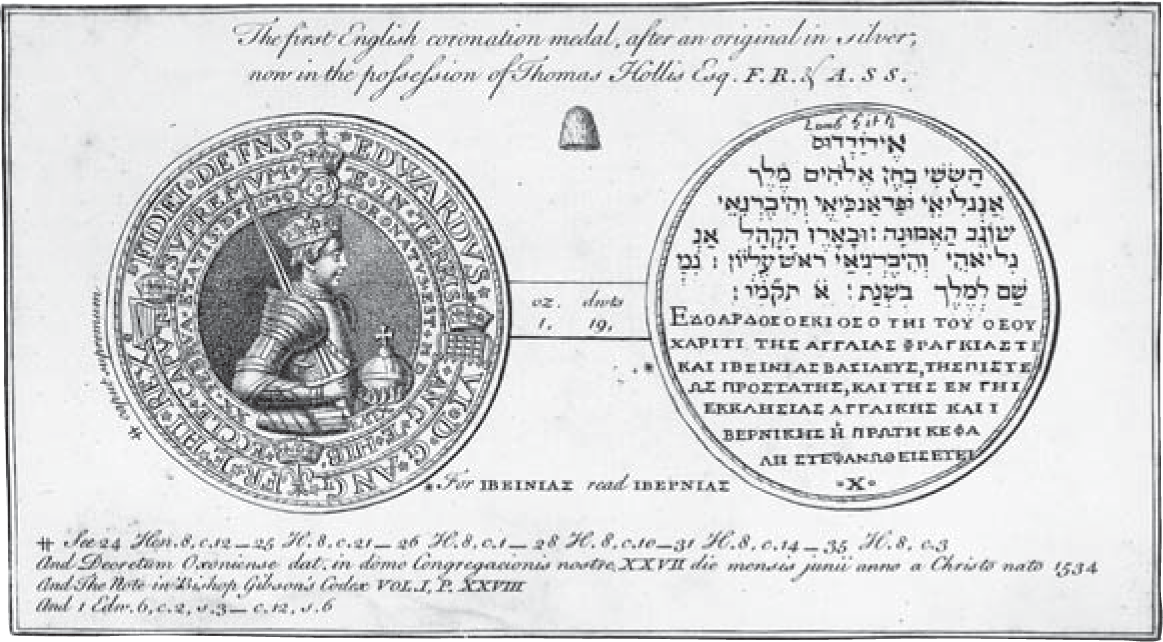

We can see this dual pattern at the very beginning of the reign, for Edward VI came to the throne in the guise of two different boy-kings. In the address which Archbishop Cranmer is said to have given at his coronation, Edward was already Josiah, exhorted to see ‘God truly worshipped, and idolatry destroyed’. The gold medal struck for the coronation made a point of stressing his supremacy, just like that of his father, or Josiah in his kingdom. Predictably, Edward as King Josiah enjoyed plays during the revels at his coronation which portrayed not merely the Pope with gilded pasteboard crown and cross but also priests in crimson and black caps: the old world of faith was mocked as superstitious and as sham as the Pope’s pasteboard.8 However, on the way from the Tower to Westminster the previous day, Edward VI had assumed the role of a very different young monarch: the fifteenth-century boy-king Henry VI. The London authorities chose to centre their pageants on those which had been used for the child king’s return from France in 1432, the work of the poet William Lydgate. The minimal modifications of Lydgate’s century-old verse and pageants were designed mainly to emphasize the royal supremacy which Henry VI had not realized he possessed.

Sydney Anglo, our leading authority on Tudor political ceremony, has considered this antiquarian revival to be a sign of panic-stricken haste: Anglo described Edward’s royal entry to the city as perhaps the most tawdry on record. But there was no particular reason why the city authorities should have needed to hurry with their plans: the choice is likely to have been considered and deliberate.9 It is worth noting the late Jennifer Loach’s observation that at King Henry’s funeral at the beginning of that month, the most significant innovation in the thoroughly traditional ceremony was the addition of a processional banner for Henry VI.10 This sounds like more than coincidence, and one can see why reference to Henry would be a useful piece of symbolism to please conservatives. Today we remember Henry VI as one of the most disastrous of English monarchs: however, in 1547 he was still a royal saint, whose cult had been increasingly popular in early Tudor England. As the Duke of Somerset himself pointed out in a self-justificatory letter to his great enemy-in-exile Cardinal Pole in 1549, Henry’s ‘childhood was more honourable and victorious than was his man’s estate’. It may be relevant, too, that the story of Henry’s childhood prominently featured Humphrey Duke of Gloucester, who provided a useful precedent for a good duke chosen as Protector.11

It took some time to provide a legal framework to move away from Henry VI and towards Josiah. Throughout 1547, conservatives could exploit the fact that Henry VIII’s exuberantly traditional Act of Six Articles of 1539 was still in force to regulate religion, and they used it to harass religious opponents for their eucharistic views. Some evangelicals imprisoned during the conservative clampdown of summer 1546 were still in gaol through King Edward’s first spring; in Worcester, a young sacramentary called John Davis was sitting in irons in his cell until April 1547, while in York there were still victims of the Six Articles legislation in prison in May, needing Privy Council intervention to get them released.12 There are several examples of new accusations being brought against evangelicals all through this year, while most remarkably of all, that April, the diocese of London received a new commission to inquire and make prosecutions under the Six Articles Act. It was headed not only by Bishop Bonner but by two of the more conservatively minded Privy Councillors, Lord St John and Lord Russell; perhaps Bonner had insisted on obtaining the commission in order to embarrass the regime, which could hardly have turned down such a request.13 Quite what the London commission actually achieved is not now clear, but the Act itself could not be abolished until Parliament was summoned at the end of the year.

Accordingly, through the spring, a welter of confusing messages came from the government. Only a month after the Six Articles commissions were issued for London, in May, a royal visitation was announced, inhibiting the bishops’ jurisdiction: the visitors were nearly all hand-picked for their evangelical enthusiasm. Yet there was almost immediate hesitation. Only a week later the Privy Council wrote in the most urgent terms to Archbishop Holgate of York telling him not to implement the inhibition as far as it affected preaching. They gave no reason, but it is likely that this particular problem resulted from delays to the proposed substitute for preaching, a book of twelve official homilies. The book was probably ready, but it had not been cleared with the conservative bishops, and it never would gain their wholehearted assent. During June Cranmer and Bishop Gardiner of Winchester started a lively and acrimonious correspondence about its contents, in which Gardiner frequently invoked the ghost of old King Henry: ‘although his body liveth no longer among us, yet his memory should in such sort continue in honour and reverence, as your Grace should not impute to him now that was not told him in his life’.14 When the Bishop of Winchester did eventually give a grudging public commendation to the homilies on 8 April 1548, he pointedly concentrated on the duty of obedience to the present king, rather than on the content of the book.15

By the end of May, the inhibitions laid on the bishops for the visitation were lifted completely, and no action on the visitation followed until the end of August. A proclamation of 24 May denounced rumour-mongering that the government was planning ‘innovations and changes in religion and ceremonies of the Church’, and it indignantly denied any such intention; Somerset took particular care to forward this to Bishop Gardiner with a courteous covering letter.16 However, those in the Province of York soon discovered how hollow this claim was, for only two days later the Privy Council was ordering the Archbishop of York to stop parishes using the Exoneratorium curatorum. This was a widely distributed book of instruction for the laity, which had originally been drawn up especially for the northern province in the fourteenth century, but which had been put into print at least eight times up to 1530.17 Perhaps the Council could justify this ban by reference to the order of 1545 enforcing universal use of Henry VIII’s official Primer, but the functions of the Exoneratorium and the Primer were not identical. This was an effort to gag the teaching of traditional religion, even before there was any new official statement to put in its place. Yet in contradiction again, throughout June there was official discouragement of aggressive evangelical preaching, a restoration of the old fast days at Court, and liturgical performances of full traditional splendour in dirige and requiem to commemorate the death of King Francis of France.18

The government seemed to be marking time through much of the summer, and not just in religious matters: during May it had looked as if England was ready to launch a new military expedition into Scotland, but no action followed for three months.19 There were good diplomatic reasons for hesitation. Negotiations for lasting peace with France were now wrecked by the French king’s death. If relations with France were to worsen once more, it would force England to take more notice of the Emperor, just at the moment when he had shattered Protestant power in Germany in a decisive turn of the Schmalkaldic War. Charles V’s victory over the Schmalkaldic League at Mühlberg at the end of April was greeted with widespread popular dismay in London, and the imperial ambassador saw it as directly affecting English religious policy. It was not a good moment for England, now dangerously isolated as an evangelical kingdom, either to champion the Reformation or indulge in military adventures.20

Yet this period of prudence was noticeably brief: the evangelical establishment was impatient to push on with the revolution. Already by the end of July the regime’s nerve was steadying, and it was picking up the threads of its programme. The homilies were finally published on the last day of the month, complete with their uncompromising assertions on the central importance of justification by faith alone. This was Martin Luther’s doctrine of salvation, which Henry VIII had deter-minedly kept at bay, particularly in his official doctrinal statement of 1543, the King’s Book: so here was a first step beyond what could be excused in terms of existing Henrician orders.21 Nevertheless, it was only one step. There was a deafening silence in this tranche of homilies about a second vital subject, the nature of the eucharist. All that the book had to offer was a promise that the eucharist would be discussed in a proposed second batch of homilies, which in fact was not to appear until the reign of Elizabeth.

The main factor was undoubtedly the Act of Six Articles. By the opening months of Edward’s reign, it is virtually certain that the key formers of official opinion, Cranmer, Latimer and Ridley, had abandoned belief in corporal presence in the eucharist, despite having maintained it in Lutheran fashion since the early 1530s. The reasons for the change are obscure, since those involved mostly had more sense than to express their opinions openly while the old king was alive: he was fiercely insistent on the corporal presence of Christ, and in his last year of life he had burnt some of those who openly disagreed with him on the subject. However, when Henry died, it became easier to rethink the question of eucharistic presence. We may consider such a shift unheroic or cowardly, but quite apart from our own safe distance from Henry VIII’s court, we ought to remember not only the motive of fear but that of personal loyalty. Henry was Supreme Head of the Church, deliverer of England from the papal antichrist, and he ought not to be opposed openly. The sheer mesmerizing power of the old man – no mean debater of theology himself – must have inhibited his good servants in positions of responsibility from thinking new thoughts.22

From whatever combination of motives, Cranmer, Latimer and Ridley now moved in parallel with a steady tide of scepticism about Luther’s eucharistic assertions, which characterized much of central European reformed opinion in the 1540s. Buoyed up in their shifting opinions through reassessing a number of pronouncements on the eucharist by theologians of the early Church, they came to regard the Lutheran view of eucharistic presence as verging on the trivial and blasphemous. It was a more fitting tribute to God’s glory to see his presence as a spiritual fact about the service of eucharist, a revelation of his presence to true believers – not a transformation of bread and wine.23 However, while the Six Articles Act was still in force, it would have been indecorous, embarrassing and indeed illegal for them to publish their new eucharistic convictions; any such statement would have been a gift to the watchful Stephen Gardiner. After all, Gardiner was already making hay out of the fact that the King’s Book disagreed with the homilies on justification; but the Six Articles were a much greater menace than the King’s Book. The Articles said nothing specific about justification; evangelicals knew to their cost how specific they were on the eucharist.

Consequently, at this stage, official evangelical strategy was to try to persuade the conservative leadership to live with the homilies’ views on justification, exploiting genuine fears which both mainstream evangelicals and conservatives felt about more extreme radicalism – what contemporaries rather inexactly labelled Anabaptism. The radicals could be seen as overthrowing all consensus on the biblical sacraments, baptism and eucharist. As long as the bishops left the topic of eucharistic presence to one side, it would be possible to stress that all bishops were in broad agreement on theological basics in comparison with the radicals, and so the eucharist could act as a focus of unity rather than of division. Nicholas Ridley was sent as emissary from the Privy Council to Bishop Gardiner with this message, and according to his own account he said to Gardiner, ‘You see many Anabaptists rise against the sacrament of the altar; I pray you, my lord, be diligent in confounding of them.’ Ridley and Gardiner were, after all, both in commission investigating Kentish radicals at the time.

However, a conservative memory of the conversation was slightly more pointed: Ridley was heard to say, ‘Tush, my lord, this matter of justification is but a trifle, let us not stick to condescend herein to them [that is, radicals]; but … stand stoutly in the verity of the sacrament: for I see they will assault that also.’ However biased this account, there was an awkward ambiguity in Ridley’s stance on eucharistic presence, which was also reflected in a Paul’s Cross sermon he delivered on the subject later in 1547; his apparent endorsement of the reality of Christ’s presence in the eucharistic bread and wine would long afford him embarrassment and fuel conservative attacks on him.24 Yet the appeal to a common solidarity against the radicals was an important factor during the Somerset years in preventing complete schism and gaining enough consent for change among the bishops. Cranmer, after all, did make genuine and serious efforts to curb various varieties of theological radicalism. When the government issued a commission against heresy in spring 1549, the leading churchmen among the commissioners were a bipartisan group, traditionalist and evangelical, although significantly this was not the case in altered political circumstances two years later.25

In late August 1547, not only did the government launch its long-postponed invasion of Scotland but also the invasion of traditional religion, via the royal visitation of the Church. Bishops Bonner and Gardiner found that there were limits to conciliation when they protested both about the scope of the visitation and the content of the homilies; their bluff was now called, and they ended up in gaol. The injunctions provided for the visitors were announced proudly to the evangelical movement across Europe, for they were issued in condensed form in Latin translation, probably by an overseas publisher, alongside the English version used in the visitation itself; the demand for the Latin translation abroad was enough to produce two different editions.26 The content of the injunctions amounted to a careful reworking of Henrician injunctions in the evangelical interest. As Eamon Duffy has recently demonstrated in detail, in certain respects they stepped out beyond Henry in ways which would inflict deep wounds on traditional devotion. For instance, processions were forbidden, striking a major blow against the dramatic use of movement in liturgy, and recitation of the rosary was comprehensively condemned. But even more importantly, there was a deliberate hidden agenda behind many injunctions. As Cranmer confided to his faithful secretary Ralph Morice, because of worries about public opinion, ‘the council hath forborne especially to speak [of abuses], and of other things which gladly they would have reformed in this visitation, referring all those and such like matters unto the discretions of the visitors.’27

In other words, given the pronounced evangelical views of nearly all visitors and the use which they would make of their ‘discretions’, the real visitation programme exceeded what appeared on paper. For instance, in a clever extension of Henrician orders against ‘feigned miracles, pilgrimage, idolatry and superstition’, the visitation injunctions said that even images in stained-glass windows should be removed if they had been the object of devotion. Such devotion was highly unlikely, and went well beyond what continental connoisseurs of iconoclasm would have considered necessary, but it provided an excuse right at the beginning of the visitation for the wholesale destruction of stained glass in Westminster, a high-profile venue no doubt deliberately chosen to set fashions elsewhere.28 Similarly, the injunctions forbade the burning of candles in front of the figure of the rood (the figure of the crucified Christ), flanked by figures of Mary and John standing above chancel screens: this had been one of the few exemptions for devotional lights which Henry VIII had allowed. Eamon Duffy points out that the ban on rood lights had the incidental advantage of attacking many devotional guilds which in Henry’s reign had relocated their lights from other church images to the rood; however, it was also fatal for the rood itself, one of the most spectacular pieces of furniture in any traditional church, as it reared above the chancel screen, dominating the laity’s view as they looked towards the altar or pulpit. Without official sanction for its lights, the rood became like any other church image, and equally vulnerable to the charge of being abused for devotion. The result in London was almost universal destruction of roods. Even the conservative stronghold of St Paul’s Cathedral suffered, although there, to grim conservative satisfaction, the rood group figures fought back by collapsing and causing the death of one of the workmen involved in pulling them down.29

Throughout the kingdom, what must have been most memorable about the visitation was its gleeful destructiveness, utilizing public ridicule against traditional devotion on a scale not seen since Thomas Cromwell had orchestrated a similar campaign in 1538. During the autumn, just as in 1538, a setpiece London sermon at the open-air pulpit of Paul’s Cross ridiculed image cults, using images with moving parts as comic visual aids; the preacher, Bishop William Barlow, was a prominent former client of Cromwell. Afterwards London boys smashed up the images, amid scenes of evangelical rejoicing. Early in the visitation there seem to have been some token official attempts to reprove iconoclastic enthusiasm, but Barlow’s aggressive Paul’s Cross performance came after that, and showed that any restraint was no more than temporary window-dressing to dampen conservative fears. Indeed Barlow went out of his way to humiliate the conservative canons of St Paul’s Cathedral, whom he exposed in his sermon as having concealed one of the images he displayed.30

All over the country, through the rest of the autumn, there are glimpses of the visitors eagerly exceeding their instructions to remove superstitiously abused images and end the last remains of the pilgrimage industry. There was a bonfire of a local saint’s bones at Much Wenlock in Shropshire: a bonfire of parish church cult images in the marketplace at Shrewsbury, which we know to have happened during 1547, also seems to have been part of the visitation holocaust. In Norwich, local enthusiasts took matters into their own hands in September, when ‘divers curates and other idle persons’ toured the city’s rabbit warren of parish churches, tearing down and removing images. Notably, the Norwich city authorities did nothing more about these outrages than feebly requesting that the ringleaders (who included one leading parish priest of the city) to ‘surcease of such unlawful doings’.31

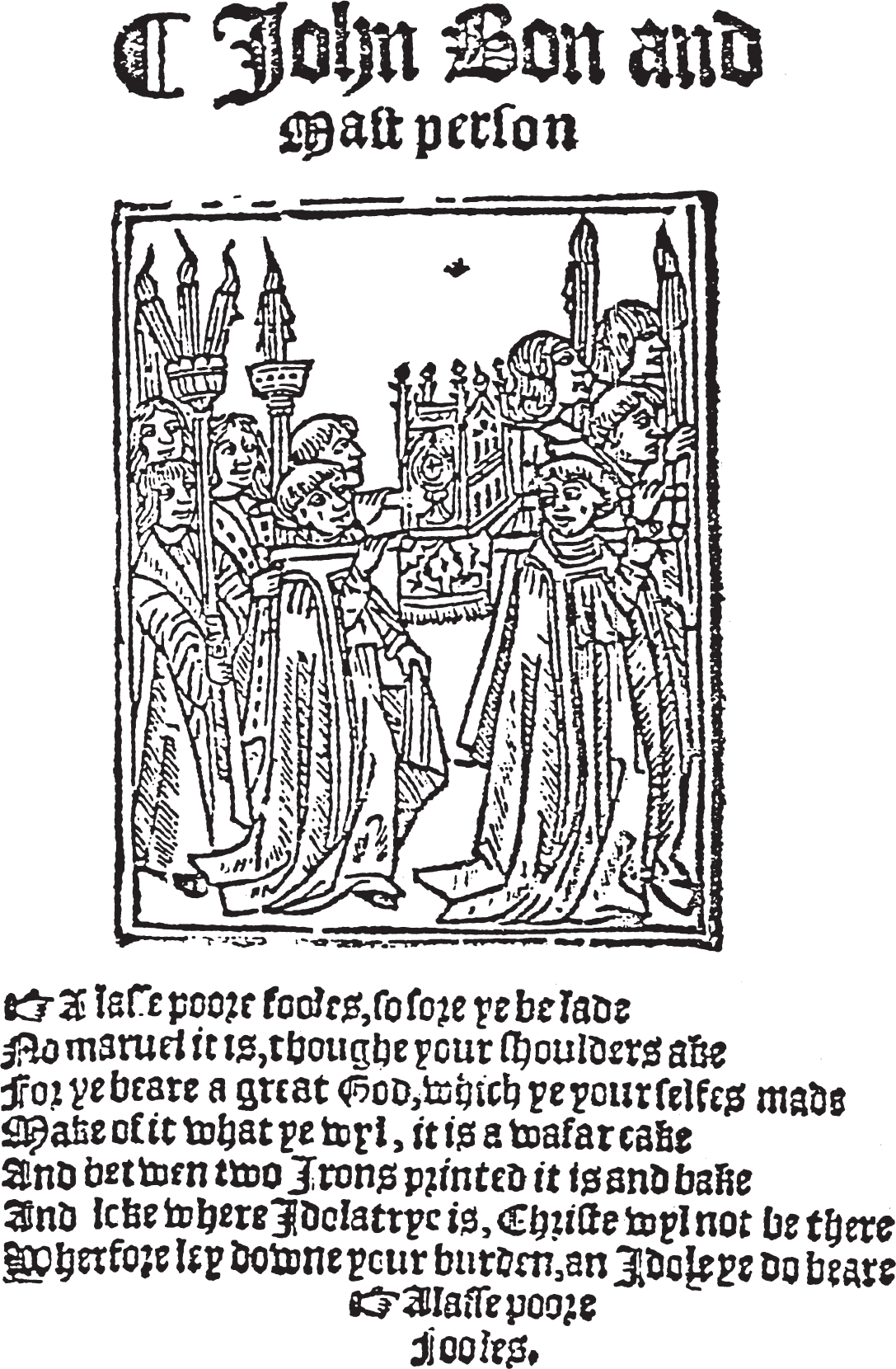

The problem for the Norwich officers was indeed to decide just how unlawful such actions could be, when the king’s representatives were indulging in equally dramatic behaviour. Far away to the north, the central parish church in Durham witnessed the remarkable spectacle of a royal commissioner jumping up and down on the city’s giant Corpus Christi processional monstrance in order to smash it up more effectively. Since the royal injunctions had just abolished all processions, one can see the rationale, but the leaping royal commissioner was not merely serving a redundancy notice: he was dancing in triumph over the corpse of the old church. His action was a symbol of how the visitors used the ‘discretion’ which the Council had given them.32 Precisely the same savagely symbolic overturning of the past was used in the following year in a literary context. A short pamphlet published a racily satirical dialogue on the eucharist, between the wily rustic John Bon and traditionalist Master Parson. It was prefaced by an illustration of a Corpus Christi procession bearing just such a monstrance as had been destroyed at Durham. However, the evangelical publisher was not using a new picture: he was economically (and perhaps with relish) cannibalizing old stock – the block came from a traditionalist devotional tract of 1516 where the context had been one of celebration and reverence.33 What is remarkable throughout all this sudden renewal of the violent Cromwellian campaign of destruction is the lack of resistance, given that most of the population must have found what was happening bewildering and distasteful. The record seems barren of activist protest: the most harm which came to the iconoclasts appears to have been from the dumb images which collapsed on to the unfortunate workmen from the rood-loft in St Paul’s Cathedral. The apparent paralysis of conservative reaction is a tribute to the policy of gradualism which Somerset’s regime had adopted at the outset of the reign; it was a gradualism in the service of calculated destruction.

Across the Channel, the evangelicals of Strassburg, the Edwardian regime’s closest friends in Europe, watched and applauded the atmosphere of festive mayhem. They had already been primed to anticipate a government programme of change to be pushed through Parliament and the Church’s equivalent representative assembly for its southern province, the Convocation of Canterbury, which duly met in November 1547.34 In these arenas, we can begin to gauge where evangelical political strengths and weaknesses lay. Opposition to the revolutionary programme was concentrated in Parliament among the lay nobility and the bishops, and in Convocation, among the Upper House of clergy. By contrast, elections for Convocation’s Lower House had by whatever means produced a crop of middle-rank clergy ardent for change, who even rather embarrassed the evangelical leadership by stepping out on their own and demanding representation in Parliament along with the lay commons.35 Equally the mood of cooperation in the Commons reflected the way in which Commons representation was biased towards the very area of the kingdom where evangelicals were most strongly represented: the urban communities of south-east England. It no doubt helped the general atmosphere of goodwill that the regime carefully avoided asking for any taxes in this session. The heresy laws were abolished, including the Act of Six Articles, so at last evangelicals could breathe easy in discussing the eucharist.

The French ambassador heard of fierce disputes on the eucharist in Parliament, but also of a clear majority wanting (as he saw it) to abolish the sacrament of the altar.36 The resulting legislation was naturally rather more nuanced than this observation of a scandalized French Catholic might suggest, and it was a classic instance of the double-message strategy in Somerset’s religious policy. Two bills on the sacrament of the altar started out, but they were eventually combined into one, which went forward to receive the royal assent. One bill embodied the gambit used by Bishop Ridley in dealing with Bishop Gardiner in summer 1547: it stressed the threat to all mainstream religion from radicals who reviled the eucharist, and it sought to curb such insolence. The other enacted a key evangelical requirement, communion in both kinds. When these were combined, the passage of the bill lost the evangelicals nothing and gained them a major step forward. Their opponents were divided, perhaps because they were deprived of Gardiner’s incisive leadership, for the government had made sure that he was still languishing in prison after his September protest against the royal visitation. Five conservative bishops voted against the sacrament bill, unimpressed by its fierce penalties for profanation of the eucharist, but five more conservatives, including the veteran champion of the old faith, Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall of Durham, were seduced into voting for it. Did they know that riding on the back of this legislation, though not announced in it, was a further incremental step of change? The restoration to the laity of communion in both kinds was made the excuse for the Council to publish a vernacular Order of Communion to be inserted into the Latin mass, and to be used throughout the realm from March. Josiah was purifying by stealth.37

There was a clear difference in atmosphere between Lords and Commons. The Commons were perfectly prepared to forward the progress of legislation abolishing compulsory clerical celibacy, which had also just been given an overwhelming endorsement in the Lower House of Convocation. The bill went on to die in the Lords, and clerical marriage was not properly legalized by Parliament until 1549, after bills had been delayed by continuing strenuous opposition in the Lords.38 Despite this, Cranmer clearly felt that the degree of endorsement which clerical marriage had received from clergy and legislators was enough for the Church to behave as if it was fully legal; he himself was already living openly as a married man in 1547, and within a year, routine official documents emanating from Lambeth Palace began mentioning clerical wives.39 In fact, in the Commons, government religious legislation only seriously faltered over the future of chantry lands once the chantries were dissolved. On this matter, many knights and burgesses were angry at the prospect of losing community assets for no obvious gain, and the obstruction had to be dealt with by some direct deals with certain particularly noisy borough representatives. This was the only time in Edward’s reign when any official measure of religious change ran into trouble in the Commons, and even though the chantry dissolution Act preamble contained an aggressive attack on purgatory, opposition to it does not seem to have been on religious grounds. In any case, as the imperial ambassador sourly observed, protest ran in parallel with eager anticipation of another shareout of church lands among those able to afford it.40

While this Parliament continued, the final ingredient was added to the Edwardian Reformation with the arrival of distinguished refugees from abroad. The first prominent men were two renegade former leaders of the Italian monastic revival, Bernardino Ochino and Pietro Martire Vermigli, known in England as Peter Martyr. They were given red-carpet treatment; their travel expenses from Strassburg were refunded to Archbishop Cranmer by the Privy Council, the huge sum of £126.41 Within a month Ochino had been authorized to set up an independent congregation in London catering mainly for Italians, but also for any other ‘strangers’ (that is, resident aliens) who might choose to attend. It was never large, but it has the distinction of being the first officially recognized foreign Protestant congregation in England, anticipating by three years the much better known Stranger Church led by the Polish evangelical Jan Laski. Clearly the regime was not sufficiently worried by the Emperor’s wrath to avoid openly harbouring refugee reformers. Perhaps Charles V might overlook the reception given to Ochino and Martyr, since they were not his subjects, but even before that, it had not escaped the notice of imperial officials that Cranmer was giving employment to Low-Countries-born Pierre Alexandre, a former chaplain to the Emperor’s sister, Mary of Hungary.42 Later arrivals, particularly prominent Strassburg reformers like Martin Bucer or the Spanish biblical translator Francis Dryander (Francisco Enzinas), were also very much the Emperor’s concern: yet they were still treated as heroes in England. This demonstrates the priorities of Edwardian government. If there is any one respect in which the Edwardian Reformation was different in flavour from the later Church of England, it was in the fervent Protestant internationalism which it displayed: there was little sense of any distinctive English ecclesiastical identity, and there was a longing for England to stand at the centre of a renewed universal Church at a time of particular military and political crisis for the reformed movement.

The inauguration of Ochino’s congregation in the City in January 1548 was an extraordinary affair, for Cranmer sadistically insisted on the close involvement of Bishop Bonner, as ordinary of the diocese of London. Bonner was badgered into finding a place for Ochino to preach; Cranmer thanked him warmly for his efforts, but then told him to make sure that there were enough forms for the Italians to sit on, ‘because their manner is not long to stand’. At the same time, he invited Bonner to come with him to hear Ochino’s inaugural sermon, and to show that this was a request expecting the answer yes, he arranged for the bishop to entertain the preacher to dinner. Unfortunately, said Cranmer, with infuriating courtesy, he himself would be prevented from joining them by a prior engagement with Protector Somerset. All this was part of a letter which must have given Cranmer particular pleasure to write, because it was a personalized version for Bonner’s benefit of a general circular ordering the bishops on Somerset’s authority to forbid candles at the imminent feast of Candlemas, together with prohibitions on ashes on Ash Wednesday or palms on Palm Sunday. Bonner would have to send this out to his fellow-bishops in the Province of Canterbury, since he was ex officio registrar of the province. The letter was written exactly twelve months after King Henry had drifted into his final coma.43 One could hardly find a more emphatic witness to the rapid success of evangelicalism and the policy of a step-by-step revolution.

So at the end of this first year Somerset and his colleagues had gained everything they needed for further progress towards purifying the Church. They had eliminated any serious opposition within the Privy Council. They had enshrined the doctrine of justification by faith in the Church’s official statements, elbowing aside the statements on justification in the King’s Book. They had robbed the Church’s traditional liturgy of the drama, movement and visual impact which gave it much of its power, dealing a fatal blow to the use of sacred objects in devotion – not just images, but the symbols used in the ceremonies of Candlemas, Ash Wednesday and Palm Sunday. They had persuaded Parliament to pull down the defences of traditional religion provided by the heresy legislation, and to deliver the coup de grâce to the moribund purgatory industry. They had secured a de facto acceptance of clerical marriage, opened up new possibilities in the celebration of the eucharist, and begun recruiting star overseas theologians to link the English Church to the international reform movement.

The pattern of this first twelve months could be demonstrated over the next two years: constant repetition of the themes of unity and peace, and careful, incremental wearing down of opposition, at each stage accompanied by ostentatious and empty gestures of reassurance to Charles V and to conservatives at home. Naturally the government exploited the English habit of deference to the monarchy, in a country where it was customary to doff one’s cap when mentioning the king or reading royal letters. One wonders which spin-doctor had the brain-wave of nicknaming the new English Prayer Book of 1549 ‘the King’s Book’, to blot out memories of Henry VIII’s embarrassingly conservative doctrinal book of 1543, which had gone under the same name.44 The Chapel Royal, the king’s personal religious establishment, which followed him from palace to palace, was an obvious model for other churches to follow. Even while the committee preparing the Prayer Book was still at work in September 1548, Protector Somerset wrote to Cambridge University, almost certainly circularizing Oxford and other major churches at the same time: in the cause of uniformity they should follow Chapel Royal liturgical practice, which by that stage clearly included draft versions of the new vernacular eucharist, mattins and evensong.45 The specialist royal chapel community of St George’s Chapel, Windsor, was one of the first major churches to silence its organs: its organists were being given other duties as early as autumn 1550, and the instruments themselves may already have been destroyed by then.46

The government paid a great deal of attention to other places which could act as showcases for liturgical change and propaganda. For instance, among certain key churches in the provinces where the leadership was sympathetic was Worcester Cathedral, placed in a centre of trade for the west Midlands and the Welsh border. Not only would an edition of the 1549 Prayer Book be printed at Worcester to supply the western market, but the drastic and precocious Edwardian changes in the cathedral are recorded for us in a detailed chronicle kept by a dismayed local conservative observer. Worcester Cathedral under Dean John Barlow, brother of William, one of the leading evangelical bishops, meticulously and immediately observed the government’s timetable of liturgical change, and the dean was even inclined to go faster and further than official orders prescribed. So he removed the reserved sacrament from his church in October 1548, well before many leading English churches and without any specific government instruction, and he introduced the new English Prayer Book on Easter Tuesday 1549, more than six weeks in advance of the Whitsun deadline ordered in Parliament’s enactment.47

Above all, the regime was conscious of the importance of the capital. Nicholas Ridley observed as its bishop in 1551 that from London ‘goeth example … into all the rest of the king’s majesty’s whole realm’.48 The city was a large and complex community to manage, and to begin with, both the cathedral staff and the bishop (Edmund Bonner) provided centres of resistance to change, rather than cooperation. It was therefore important for London to be given its own showcase, more closely under the government’s control: the adjoining community of Westminster, with its complex of royal palaces, its meeting place for Parliament and the former royal abbey church, which between 1540 and 1550 briefly became the cathedral of a new diocese. Great care was taken to turn Westminster into a miniature version of the reformed city-states of the Continent. The royal injunctions for Westminster diocese in September 1547 specified that Sunday service was to end in the churches of the community by nine o’clock, so that priests and laity could resort to the sermon in Westminster Cathedral, unless the churches themselves had a sermon. All Westminster clergy were to turn up to every divinity lecture in St Stephen’s College.49 The college’s suppression in 1548 along with all England’s remaining chantries put paid to this last idea, but help was at hand. Bishop Hugh Latimer was given lodgings in the cathedral precincts with the Dean of Westminster, William Benson, to act as a resident celebrity preacher for this model community; the palace of Whitehall could still boast its own up-market version of London’s pulpit at Paul’s Cross with Henry VIII’s recently built open-air preaching place in the Privy Garden. This became the setting for some of Latimer’s most celebrated sermons.50

Given the progress made in 1547, during 1548 the evangelical establishment could afford to indulge its friends and gag its opponents. It let loose propaganda by tolerating evangelical preaching and making little effort to control printing; around three quarters of all books published in Somerset’s time were on religious themes, virtually none defending traditional religion. This year represented a peak in the numbers of book and pamphlet titles published in English, which would not be exceeded until after 1570. The Protestant chronicler Bishop Thomas Cooper later looked back on 1548 as the time when ‘by reason of continual preaching and teaching of divers that were to that office [i.e. duty] appointed: the people in many places declared themself very forward and ready to forsake their old religion’.51 Simultaneously the regime hamstrung the opposition by heavily restricting preaching, a paradoxical step for an evangelical church to take, and one which rather puts into perspective Somerset’s supposed spirit of liberal tolerance.52

Henry VIII, or rather Thomas Cromwell, had obliged parish clergy to preach quarterly in their own churches, but now Cromwell’s heirs overturned the measure: from April 1548, only a very restricted list of clergy with a royal licence had the right to preach at all, and inevitably most of them were card-carrying evangelicals.53 In the West Country, by contrast, the alarmingly talented conservative preacher Roger Edgeworth found himself banned from preaching in his numerous benefices and multiple cathedral offices for virtually the entire reign.54 The rhetoric employed in these preaching prohibitions was the Henrician theme of suppressing seditious and contentious preachers, but it was clear that apart from the inevitable Anabaptists, sedition and contention were labels for traditionalists, particularly if they tried to expound eucharistic theology. The government line was that the eucharist should not be discussed, because an official decision was soon to be made about it in order to preserve national unity: again, a standard Henrician refrain now put to frankly partisan use. Thus it was on these grounds that Bishop Gardiner was told to avoid the subject of the eucharist when he was made to preach a test sermon in May 1548, and his ostentatious disobedience to this instruction was one of the chief pretexts for his immediate arrest and permanent removal from active Edwardian politics.55

The same reason – that a major decision on liturgy was imminent – was used again when preaching was forbidden altogether in September 1548, by which time a committee was indeed putting the finishing touches to a uniform prayer book for the realm. There were enough conservatives on this committee to give it a respectable appearance of consensus, yet as soon as the group had done its work, the government moved the goalposts again. The committee appears to have prepared an agreed statement on eucharistic doctrine, which was then doctored before Parliament was scheduled to debate it. The omissions in the revised document concerned adoration of the eucharistic elements, which had been a subject of evangelical attack through that autumn.56 Adoration was naturally a key issue for anyone who believed in the corporal presence of Christ in the eucharist, and it was linked to the custom of reserving eucharistic bread in the pyx. Far from avoiding contention, a number of strategically high-profile churches like Worcester Cathedral and York Minster abandoned reservation during the autumn.

Indeed, throughout autumn 1548, in blatant defiance of its own supposed total ban on preaching, the Privy Council condoned prominent pulpit attacks on traditional eucharistic theology; this was backed up by contentious pamphlet literature, some of which was directly inspired by the court or by Lambeth Palace. John King’s survey of Edwardian Protestant printing identified no fewer than thirty-one tracts published during the year supporting something like the new official line on the mass.57 Not all of this literature exactly conformed to the government’s agenda: on occasion it was critical of official hesitancy in attacking traditional views of what the eucharist meant. Thus the dialogue between John Bon and Mast’ Person subversively portrayed pompous and conservative Master Parson as commending Cranmer’s official catechism issued in summer 1548; that unfortunate and hastily produced translation from a German Lutheran text had inadvertently left too much room in its exposition of the eucharist for a real-presence interpretation of the bread and wine. However, the embarrassed authorities were swift first to amend the text of the catechism on eucharistic matters and then to forget the book altogether; so the author of John Bon had successfully made his point.58

For the moment the thrust of official policy was negative rather than positive. It is not always realized just how long Edwardian England lacked anything resembling an officially defined doctrinal statement on the eucharist: no statement of any sort appeared until 1550, well after the first Prayer Book was issued, and the process of definition was not complete until 1553. Clearly this would be one of the most fraught issues in any Reformation. Traditionalists would be most likely to rally to resist change in the mass, as became only too obvious in the 1549 western rebellion, and evangelicals might split along the fault lines which had already destroyed their unity in Europe. There was an extra international dimension to the problem, quite apart from the Edwardian establishment’s usual preoccupations with Charles V: the evangelicals of central Europe, principally Bullinger and John Calvin, were seeking an understanding on the eucharist, which eventually resulted in the Zürich Agreement or Consensus Tigurinus in May 1549. In 1548–9 it would have been fatal for England, the most important surviving evangelical power in Europe, to make any official pronouncement on the eucharist while delicate efforts were being made abroad to heal the twenty-year-old wounds of the eucharistic quarrel between Luther and Zwingli, and to counteract the disaster for evangelicals represented by Charles V’s Interim. The implications of the Consensus for the afterlife of the Edwardian Reformation will concern us in Chapter 4 (here); what is important to note now is that only after mid-1549 was it possible to create an official doctrinal or confessional statement for England which would not unduly divide evangelicals at home, or complicate international relationships.

Therefore, in 1548, definitive statements lay in the future. In December of that year, the government staged a four-day debate on the eucharist in the House of Lords, a gathering of Councillors, peers and bishops of which we have an abbreviated though still eloquent record. Somerset entered the debate newly briefed on the eucharist by an English translation of a short tract by Peter Martyr, the first recorded occasion on which the refugees had made an active contribution to England’s religious politics.59 The whole occasion may have been an example of the Protector’s readiness to try out new ideas; there was nothing else like it in the whole of England’s Reformation, and it was the nearest English equivalent to the set-piece disputations which launched the Swiss Reformation in the city of Zürich in the 1520s. Yet unlike the Zürich disputations, it led nowhere, in the sense that it produced no policy statement or legislation: all that the debate did was to expose the doctrinal divisions among the bishops, and the doctrinal solidarity between leading evangelical churchmen and laypeople, before Parliament went on to forward the legislation authorizing the Book of Common Prayer for the royal assent.60 The event thus showed that for all the tactical gains which the reformers had made, as yet the balance of political forces had hardly shifted between traditionalists and evangelicals. This meant that the regime must persevere in its religious policy with the double-message strategy which so far had proved such a success.

The eucharistic stance of the 1549 Prayer Book itself was an example of speaking with two voices. On the one hand, in constructing the service of eucharist and giving it a distinctive dynamic, Thomas Cranmer so manipulated the liturgical material at his disposal that his rite expressed the personal convictions which he had reached in the previous three years, and which he had spelled out in the December Lords debate – that is, that there is no corporal presence of Christ in bread and wine, and that the self-offering of Christ on the cross has nothing to do with the congregation’s offering of thanksgiving in each individual eucharist. In this respect, as I have argued at length elsewhere, the eucharistic theology of the first Prayer Book was no different from that of the second, and it had parted company with Luther, let alone with Henry VIII.61 However, this was not the whole story. Notoriously, there was enough scope for traditionalist ceremony in the book to scandalize foreign reformers not in Cranmer’s confidence, and to enable its eucharist to be dressed up as something very like the old mass by those who wanted to. The book ostentatiously avoided committing itself to any one view of eucharistic doctrine in its catch-all title at the beginning of its eucharistic service: ‘The supper of the Lord and the holy communion, commonly called the mass’.

That word ‘mass’, hated by evangelicals, including the king himself, had been generally absent from official statements during 1548, but its ungracious return now was probably the pilot which guided the liturgy past the shoals of conservative hostility in Parliament. The evangelicals could afford to put up with its presence, because the Prayer Book still did not constitute an official doctrinal statement on what the Church of England believed about the eucharist. Liturgical practice was not based on a single theological statement: lex credendi (a rule for belief) was not in this case implied by lex orandi (a rule for worship). Even the catechism which the book contained failed to discuss the sacraments at all, uniquely among official catechisms of the period.62 There can be no greater proof of the stopgap nature of the 1549 Prayer Book than this. Practising Anglicans who lived through the 1960s and 1970s may recall the proliferation of little floppy books which contained experimental services before the arrival of the Alternative Service Book: it is in this light that we might regard the Prayer Book of 1549. In Ireland it was allowed to endure throughout Edward’s reign, but the Irish agents of Edwardian government were very cautious in their introduction of change, showing a greater sensitivity to the Irish situation than would be the case in later reigns: the compromises of the 1549 book proved well suited to the complexities of the Edwardian Irish Church.63

The absence of any officially defined eucharistic theology within the 1549 Prayer Book was spelled out in public by Richard Cox, Dean of Christ Church, Oxford, when he summed up four days of formal debate on the eucharist in Oxford University’s Divinity School on 1 June 1549 – in other words, nearly three months after the Prayer Book was published. The Oxford debate was one of a pair held in the two universities in the presence of the royal visitors who had been sent to bring the universities into line on religion. Of the paired debates, that in Oxford was the more important, for conservatives were much stronger in Oxford than in Cambridge, and the evangelical case was led by the international star theologian Peter Martyr. The king himself annotated his copy of the officially published Latin account of the Oxford proceedings, picking out rival arguments with partisan enthusiasm; the book sold well, not only in England, but also in Germany and Switzerland, leading to a second Zürich edition in 1552.64 Cox, presiding at the debate, extravagantly praised Martyr’s presentation of the case, emphasizing that he had ‘singularly well answered the expectation of the great magistrates, yea, and of the king’s majesty’. However, Cox also announced that he was not going to deliver a formal judgement about victory between champions of the government line and the conservative opposition, on the grounds that the time was not ripe: ‘but it will then be decided when it seems good to the king’s majesty, and to the leaders of the Church of England’.65

For the moment we will postpone consideration of whom Cox might have meant by the ‘leaders of the Church’, and note the steps which created England’s official eucharistic theology. The first stage was the publication in summer 1550 of Archbishop Cranmer’s Defence of the true and Catholic doctrine of the sacrament of the body and blood of our saviour Christ. Now there was no question of double messages. Cranmer had been drafting this book already in the contentious autumn of 1548, so Cox was disingenuous in talking of a future decision: the decision was there, only waiting a suitable time for announcement.66 Cranmer’s work emphasized on its title-page that it was written by the ‘Primate of all England and Metropolitan’, and it did no harm to the cause of evangelical consensus on the eucharist when the following year Cranmer was forced to amplify the message of the Defence, writing an Answer to a published attack by his imprisoned arch-rival Stephen Gardiner. The essence of Cranmer’s exposition was to affirm a spiritual eucharistic presence granted by grace only to the elect believer, not to all who received bread and wine. Cranmer’s modes of expressing this doctrine were closer to Bullinger’s than to Calvin’s interpretation of their agreement in the 1549 Consensus Tigurinus.67 The next step was the creation of a liturgy which was a more obvious fit than the 1549 book for the theology of the Defence and the Answer. This was done by 1552, when Parliament passed the second Act of Uniformity, to which a new Prayer Book was annexed, and which declared the revision to be the only permissible liturgy in the realm. The third and final stage was the eucharistic discussion in the long-delayed doctrinal statement of the Edwardian Church, the Forty-Two Articles, published only a few weeks before the king’s death.

Thus the process of defining what the regime believed about the eucharist stretches seamlessly from 1548 to 1553. It is evidence that neither the popular commotions of 1549 nor the transfer of power from the Duke of Somerset to John Dudley Earl of Warwick made a material difference to aims and objectives, only to strategy. Conservative noblemen joined the coup of October 1549 against Somerset, led by Wriothesley, the Lord Chancellor who had been ousted in 1547. However, the reality of the coup was that the evangelical establishment under Warwick’s leadership had spearheaded Somerset’s overthrow. The conservatives found themselves quickly outmanoeuvred and their concerns were given the most cursory consideration, whereas, within a few days of Somerset’s surrender, the King’s Privy Chamber was being reinforced with evangelical gentlemen and the Privy Council were making overtures to the reformed strongholds of Zürich and Berne for a General Council – in effect, an evangelical international. By the end of October a proclamation emphasized not only that none of Somerset’s religious changes would be abrogated, but that the government would ‘further do in all things, as time and opportunity may serve, whatsoever may lend to the glory of God and the advancement of his holy word’.68

The Spanish refugee Francis Dryander, always an acute observer who seems to have charmed people into giving him confidential information, was able to look back on what he had observed in England over that autumn of 1549 and tell Bullinger in Zürich that he had ‘not only seen the outward and deplorable appearance of the change, but the purposes of the leading actors are well known to me … religion is now in a better condition than it was before the imprisonment of the Protector’.69 He was writing at the beginning of December, on the eve of a second and very differently led coup attempt which, in its failure, was one of the most decisive moments of the reign. The conservative grouping around Wriothesley now tried to isolate Warwick and associate him with Somerset in a treason charge; their defeat sidelined them from power and brought to an end any need to conciliate traditionalist opinion. On Christmas Day 1549 a royal circular to the bishops made this shift of power to the evangelicals brutally clear: it reinforced the message of the earlier proclamation by ordering the destruction of all Latin service books.70 Bonfires of books followed all over England, reviving the set-piece public feasts of destruction seen in the royal visitation of 1547; and this time it was the bishops who willy-nilly were forced to act as masters of ceremonies. At last the revolution was secure.

During 1550, moreover, the episcopal bench itself witnessed a decisive shift in the balance of forces which had hobbled the pace of religious change throughout the Somerset years. Through confrontations with the newly aggressive government, plus one death and two forced retirements, conservatives lost no fewer than seven sees out of a total of twenty-seven. Bonner and Gardiner were already in gaol; by the end of 1550, Rugg of Norwich, Tunstall of Durham, Wakeman of Gloucester, and Day of Chichester had gone from their sees. Veysey of Exeter was negotiating the terms of his retirement, completed in 1551. All but one of these dioceses eventually went to evangelicals, and the one exception among the new bishops, Thomas Thirlby, was sent to Norwich as a way of removing him from the showcase city of Westminster, which was reunited with the diocese of London under the safe leadership of Nicholas Ridley.71 Furthermore, Thirlby was an absentee diplomat not disposed to cause trouble, and he arrived at Norwich to find an evangelical fait accompli. Archbishop Cranmer had exploited his powers of visitation in a vacant see (sede vacante) to maintain the momentum set by the book-burning order: Norwich diocese became a guinea-pig for more general changes. In February 1550, Cranmer imposed as visitors on the unwilling and still very conservative clergy of the Norwich diocesan establishment his trusted household servants Rowland Taylor and William Wakefield.72 One notes the significant contrast with Cranmer’s action in a previous vacancy-in-see on 6 December 1549, that is, just before the failed conservative attempt at a second coup: when Gloucester diocese had fallen vacant on Bishop Wakeman’s death, the Archbishop had granted the custody of spirituals to John Williams, a clergyman of the diocese who showed no signs of sympathy with the evangelical cause.73

Unlike Williams in Gloucester, Taylor and Wakefield seized the opportunity offered to them, and went to work in Norwich with zeal. They worked to visitation articles and injunctions which were a development of Cranmer’s diocesan visitation articles of 1548; in turn their instructions formed the basis of subsequent visitation inquiries elsewhere. The Norwich articles and injunctions had certain novel features: they were notably alert for symptoms of Anabaptist belief in East Anglia, which presumably reflected official fears about the aftermath of the 1549 stirs. However, they also intensified the attack which Cranmer had made on traditionalism in the Canterbury diocese two years before. For instance they pitilessly specified a range of traditionalist ceremonial which could no longer be used to dress up the eucharistic rite of the 1549 Prayer Book as if it were ‘the old popish mass’: an abuse which was already infuriating reformers a few months after the book’s publication.74 Moreover, in typically Edwardian fashion, their actions outstripped their instructions on paper. Their articles still talked of altars, and even at one point mentioned ‘the high altar’, implying that there might be other altars within the church building. Yet in their relatively brief time in visitation, the visitors masterminded the destruction of stone altars throughout East Anglia, a pilot scheme which would be extended to the rest of the kingdom by the end of the year.

At the same time, now that the diocese of London was vacant through the deprivation of Edmund Bonner, Cranmer began formally exercising sede vacante jurisdiction there. This only gave legal sanction to existing reality; he had already been acting as de facto bishop of London in Bonner’s place since the previous summer. So now, with the dioceses of Canterbury, London and Norwich at Cranmer’s disposal, the capital and the entire English seaboard from the Wash to the Weald was under his direct control. He may have felt that London diocese demanded more high-powered action than Norwich, because a royal visitation of London was announced in February. Although no further proceedings can definitely be traced to this royal visitation, an unattributed set of articles very like those for Norwich may relate to it, and a month later the articles also seem to have been circulated throughout the kingdom in Edward’s name. In any case, Nicholas Ridley drew on both this set and the Norwich articles and injunctions when he held his own visitation as Bishop of London later in the year.75 By 1552 even Bishop Bulkeley’s remote Welsh diocese of Bangor was facing a developed version of the articles which Cranmer’s henchmen had devised for Norwich and London back in winter 1550.76

After the pace set by Cranmer that winter, Edwardian religious policy hardly needs description. Even while the young king was dying, its destructive consequences were still unfolding, as the nation’s churches were robbed of their traditional ornaments, bells and plate. However, two factors slowed down further positive change. One was the question of priorities between national and international reformation. Cranmer’s dearest wish was to create a general council of reformers which would outshine the false Council of Trent, and to draw up unifying doctrinal statements for the reformed universal Church. I have argued elsewhere that it was only when the major continental reformers showed themselves lukewarm to any immediate meeting that England was compelled to issue its own doctrinal statement, the Forty-Two Articles, long-postponed but finally issued in 1553.77 The lack of concerted international action was a disappointment for Cranmer, but there was a second and far more damaging problem: the gulf which opened up between Cranmer’s clerical circle and John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland. In autumn 1549 Cranmer had played an equivocal role in the events which had led to Somerset’s fall and Dudley’s arrival in power: the Archbishop had done what the Primate of All England should in the circumstances, reassuring his godson the king that all was well, and acting to lower the political temperature. Thereafter, through that tense time, he had been Dudley’s firm ally in his struggle to keep the conservatives at bay. Similarly, Cranmer probably saw the inevitability of the Duke of Somerset’s second removal from the Council in autumn 1551, after Somerset’s political behaviour became more erratic and dangerous for the evangelical cause.78

During winter 1552, however, Somerset was not merely disgraced but executed. This ruthless excess was only one of a whole range of issues which provoked a breach between the religious and secular leaders of the evangelical establishment. The split was never complete, mainly thanks to the vital role played by the royal servant William Cecil in maintaining communications between the two sides, but it was serious enough.79 Three basic elements in structuring the Edwardian religious revolution all suffered delay: doctrinal statement, revised liturgy and the new scheme of canon law. If the Forty-Two Articles were held up mainly because of the Archbishop’s hopes for some greater international action, no such idealism can be detected in the case of the other two projects. The Prayer Book, revised to remove the embarrassing traditionalist survivals in the 1549 book, was accepted by Parliament and stood complete in spring 1552, but, unlike its predecessor, it was not given an immediate release to the public, but was kept under wraps until the autumn.

One might argue that the postponement in issuing the Prayer Book was in order to avoid the sort of trouble which the 1549 book had caused in some parts of the country, but in 1552 there was no especial security scare to justify the long delay. That summer was the first in which the regime permitted itself some measure of relaxation, and the king set out on his first major cross-country progress through southern England. So, rather than any security worries, the delay is likely to indicate the troubled state of relations within the regime itself. This was certainly the case when the publication of the book was further obstructed at the last moment, by a row over kneeling at communion provoked by Northumberland’s imported Scots protégé John Knox. In this contest, Cranmer only defeated Knox by some passionately confrontational politicking with the Privy Council, and by the addition to the Prayer Book text of the so-called ‘black rubric’, making it clear that kneeling at communion did not imply any adoration of the eucharistic elements – a rubric only ‘black’ because it was a last-minute insertion, and therefore had to be printed at first in black, rather than in the red of the book’s other instructions and explanations.80 A more permanent disaster was the ignominious fate of the revision of canon law, Cranmer’s pet project for two decades. It marked time for most of 1552 and in the end Northumberland himself spitefully vetoed the completed draft in the spring Parliament of 1553, for reasons to be examined in Chapter 3.81 Only in the last few months did the dire prospect of losing all the gains of six years, backed up by the intervention of the dying king, reunite the evangelical leadership behind the gamble to alter the succession away from the Lady Mary and in favour of Lady Jane Grey. This gamble would have worked, if English politics had been confined to the council chamber. Alas for the revolution, the provinces had other ideas, and decisively humbled central government in an action which had no close parallel in the Tudor age.

If we review this sketch of Edwardian religious policy, we observe a driving, unrelenting energy behind it. Sir Richard Morison, an ex-Cromwellian who was one of the lesser members of the Edwardian evangelical establishment, looked back from his Marian exile with pride on the speed of it all: ‘The greater change was never wrought in so short space in any country sith the world was.’82 The continuity for this programme across the apparent political disruption of 1549 was provided by one man: Thomas Cranmer. By 1547 Cranmer was one of the longest serving figures in politics, with a nationwide clerical clientage mostly sharing his Cambridge background, and with a network of overseas contacts which still remains shadowy in its extent. Throughout the 1530s he had been able to leave secular politics to the ruthless skills of Henry’s minister Thomas Cromwell, but any evangelical politician who managed to survive the Henrician court after Cromwell’s destruction had received a formidable political training. Cranmer weathered the so-called ‘Prebendaries’ Plot’ of 1543, in which some of the most formidable conservatives in the land combined in an effort to bring him down; he also survived the dangerous summer of 1546, when many of those he knew were arrested or even burned. He and his staff had learned much about tactics and strategy.

If anyone could have kept a sense of coherence among the evangelicals in the Privy Council as they grew steadily more alarmed at Somerset’s populist antics, it was Cranmer. He was the one Edwardian bishop to live in the style of the other noblemen on the Council, maintaining his four palaces and his military resources as the equal of any other magnate.83 No doubt we ought to look elsewhere for the detailed orchestration of policy: principally to the ‘master of practices’, William Paget, ally to Cranmer and Seymour from Henry VIII’s last years into Edward’s reign.84 Yet Cranmer is always to be found at the centre of government action until the chill descended in his relations with Northumberland in 1552: he was equally involved in the two-voice policy of the Somerset years and then in the newly unleashed religious aggression perceptible from December 1549.

John Knox, reproaching Queen Mary’s persecutions in his First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women, called Cranmer ‘the mild man of God’: a judgement both inaccurate and generous, considering that in the 1552 row over kneeling at communion, the Scots reformer had experienced at first hand the streak of ruthlessness which lay beneath the surface in the Archbishop’s character.85 An examination of Cranmer’s career reveals how repeatedly ends justified means for him, so that he could cut legal corners to get the result he wanted, and even turn the prose of his enemies inside out in his liturgical work, to redeploy it in the service of the revolution.86 His instinct for self-preservation has often been mocked, but the story of supple adaptation in his public career had more to it than that: Cranmer displayed that inflexible determination to further the evangelical goal by fair means or foul which I have identified as the keynote of Edwardian policy. If anyone ensured that King Edward could play the role of King Josiah successfully and comprehensively, it was his godfather, the Primate of All England. Alcibiades Cranmer was not, but in the drama of the Edwardian Reformation, neither was he Polonius.