and

and

. What you are doing is adding 3 fifths to 1 fifth. (A “fifth” is the very specific pie slice, as seen here.)

. What you are doing is adding 3 fifths to 1 fifth. (A “fifth” is the very specific pie slice, as seen here.)The next two sections discuss how to add, subtract, multiply, and divide fractions. You should already be familiar with these four basic manipulations of arithmetic, but when fractions enter the picture, things can become more complicated.

Each manipulation is discussed in turn in the following sections. Each discussion talks conceptually about what changes are being made with each manipulation, then goes through the actual mechanics of performing the manipulation.

Up first is how to add and subtract fractions.

The first thing to recall about addition and subtraction in general is that they affect how many things you have. If you have three things, and you add six more things, you have 3 + 6 or 9 things. If you have seven things and you subtract two of those things, you now have 7 − 2 or 5 things. That same basic principle holds true with fractions as well. What this means is that addition and subtraction affect the numerator of a fraction, because the numerator tells you how many things, or pieces, you have.

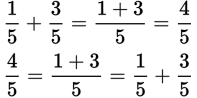

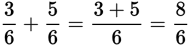

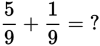

For example, say you want to add the two fractions  and

and

. What you are doing is adding 3 fifths to 1 fifth. (A “fifth” is the very specific pie slice, as seen here.)

. What you are doing is adding 3 fifths to 1 fifth. (A “fifth” is the very specific pie slice, as seen here.)

If you were dealing with integers, and added 3 to 1, you would get 4. The idea is the same with fractions. Now, instead of adding three complete units to one complete unit, you’re adding 3 fifths to 1 fifth: 1 fifth plus 3 fifths equals 4 fifths.

Notice that when you added the two fractions, the denominator stayed the same. Remember, the denominator tells you how many pieces each unit has been broken into. In other words, it determines the size of the slice. Adding three pieces to one piece did nothing to change the size of the pieces. Each unit is still broken into five pieces; hence there is no change to the denominator. The only effect of the addition was to end up with more pieces, which means that you ended up with a larger numerator.

Be able to conceptualize this process both ways: adding

and

and

to get

to get

, and regarding

, and regarding

as the sum of

as the sum of

and

and

.

.

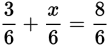

Also, you should be able to handle an x (or any variable) in place of one of the numerators:

|

becomes |

1 + x = 4 x = 3 |

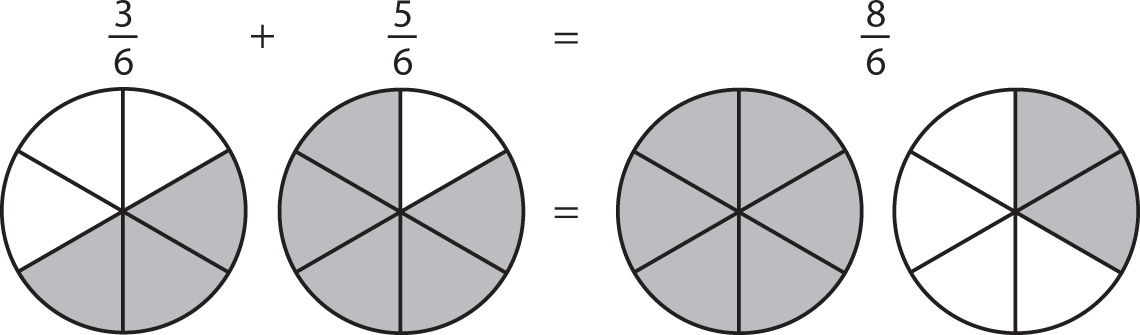

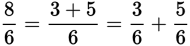

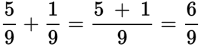

You can apply the same thinking no matter what the denominator is. Say you want to add

and

and

. This is how it looks:

. This is how it looks:

Notice that once again, the only thing that changes during the operation is the numerator. Adding 5 sixths to 3 sixths gives you 8 sixths. The principle is still the same even though it results in an improper fraction.

Again, see the operation both ways:

|

|

Be ready for a variable as well:

|

becomes |

3 + x = 8 x = 5 |

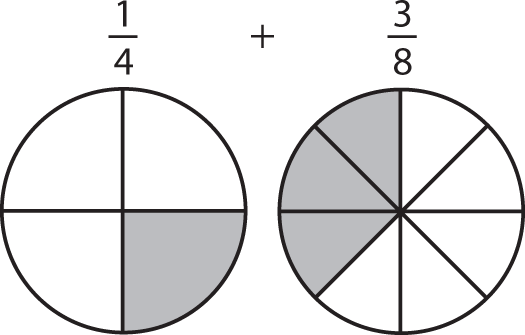

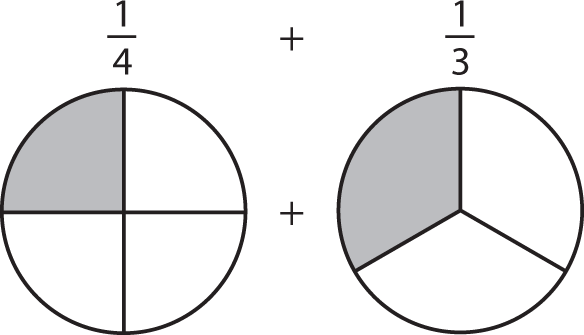

Now look at a slightly different problem. This time you want to add

and

and

:

:

Do you see the problem here? You have one slice on the left and three slices on the right, but the denominators are different, so the sizes of the slices are different. It doesn’t make sense in this case simply to add the numerators and get 4 of anything. Fraction addition only works if you can add slices that are all the same size. So now the question becomes, how can you make all the slices the same size?

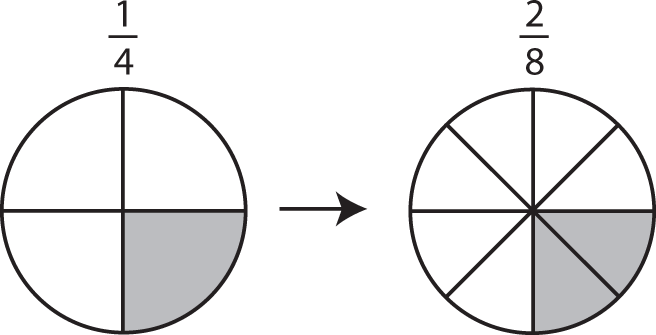

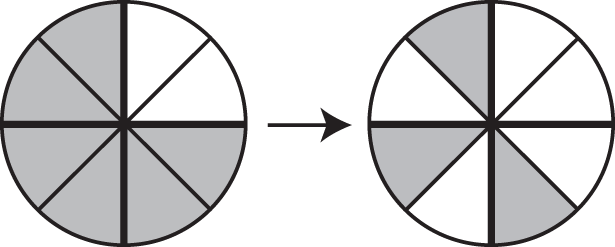

What you need to do is find a new way to express both of the fractions so that the slices are the same size. For this particular addition problem, take advantage of the fact that one-fourth is twice as big as one-eighth. Look what happens if you take all the fourths in the first circle and divide them in two:

What happened to the fraction? The first thing to note is that the value of the fraction hasn’t changed. Originally, you had 1 piece out of 4. Once you divided every part into 2, you ended up with 2 pieces out of 8. So you ended up with twice as many pieces, but each piece was half as big. So you actually ended up with the same amount of “stuff” overall.

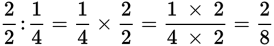

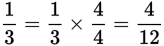

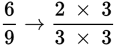

What did you change? You ended up with twice as many pieces, which means you multiplied the numerator by 2, and broke the circle into twice as many pieces, which means you also multiplied the denominator by 2. So you ended up with

. This concept will be reviewed later, but for now, simply make sure that you understand that

. This concept will be reviewed later, but for now, simply make sure that you understand that

.

.

So without changing the value of

, you have now found a way to rename

, you have now found a way to rename

as

as

, so you can add it to

, so you can add it to

. Now the problem looks like this:

. Now the problem looks like this:

The key to this addition problem was to find what’s called a common denominator. Finding a common denominator simply means renaming the fractions so they have the same denominator. Then, and only then, can you add the renamed fractions.

All the details of fraction multiplication shouldn’t concern you just yet (don’t worry—it’s coming), but you need to take a closer look at what you did to the fraction

to rename it. Essentially what you did was multiply this fraction by

to rename it. Essentially what you did was multiply this fraction by

. As was discussed earlier, any fraction in which the numerator equals the denominator is 1. So

. As was discussed earlier, any fraction in which the numerator equals the denominator is 1. So

= 1. That means that all the process did was multiply

= 1. That means that all the process did was multiply

by 1. And anything times 1 equals itself. So the appearance of

by 1. And anything times 1 equals itself. So the appearance of

was changed by multiplying the top and bottom by 2, but its value was not.

was changed by multiplying the top and bottom by 2, but its value was not.

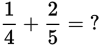

Finding common denominators is a critical skill when dealing with fractions. Here’s another example to consider (pay close attention to how the process works). This time, add

and

and

:

:

Once again, you are adding two fractions with different-sized pieces. There’s no way to complete the addition without finding a common denominator. But remember, the only way to find common denominators is by multiplying one or both of the fractions by some version of 1 (such as

,

,

,

,

, etc.). Because you can only multiply by 1 (the number that won’t change the value of the fraction), the only way you can change the denominators is through multiplication. In the last example, the two denominators were 4 and 8. You could make them equal because 4 × 2 = 8.

, etc.). Because you can only multiply by 1 (the number that won’t change the value of the fraction), the only way you can change the denominators is through multiplication. In the last example, the two denominators were 4 and 8. You could make them equal because 4 × 2 = 8.

Because all you can do is multiply, what you really need when you look for a common denominator is a common multiple of both denominators. In the last example, 8 was a multiple of both 4 and 8.

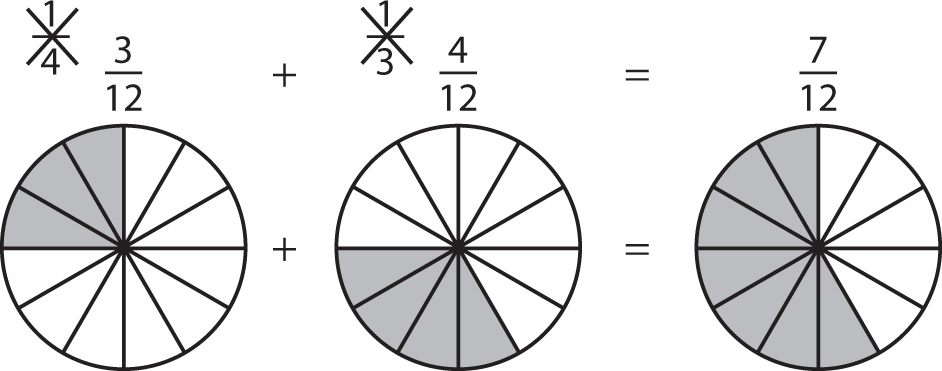

In this problem, find a number that is a multiple of both 4 and 3. List a few multiples of 4: 4, 8, 12, 16. Also list a few multiples of 3: 3, 6, 9, 12. Stop; the number 12 is on both lists, so 12 is a multiple of both 3 and 4. Now change both fractions so that they have a denominator of 12.

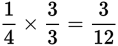

Begin by changing

. You have to ask the question, what times 4 equals 12? The answer is 3. That means that you want to multiply

. You have to ask the question, what times 4 equals 12? The answer is 3. That means that you want to multiply

by

by

:

:

. So

. So

is the same as

is the same as

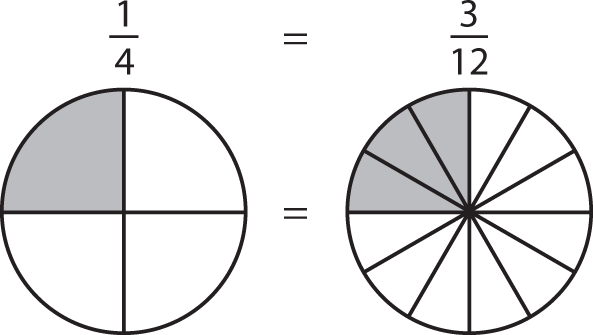

. Once again, look at the circles to verify these fractions are the same:

. Once again, look at the circles to verify these fractions are the same:

Now you need to change

. What times 3 equals 12? The answer is 4 × 3 = 12, so you need to multiply

. What times 3 equals 12? The answer is 4 × 3 = 12, so you need to multiply

by

by

:

:

. Now both of your fractions have a common denominator, so you’re ready to add:

. Now both of your fractions have a common denominator, so you’re ready to add:

And now you know everything you need to add any two fractions together.

Here’s a recap what you’ve done so far:

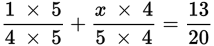

|

|

|

|

|

Common multiple of 4 and 5 = 20 |

|

|

|

|

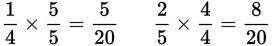

This section would not be complete without a discussion of subtraction. The good news is that subtraction works exactly the same way as addition! The only difference is that when you subtract, you end up with fewer pieces instead of more pieces, so you end up with a smaller numerator.

Consider the following problem. What is

−

−

?

?

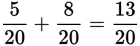

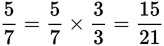

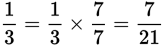

Just like addition, subtraction of fractions requires a common denominator. So you need to figure out a common multiple of the two denominators: 7 and 3. The number 21 is a common multiple, so use that.

Change

so that its denominator is 21. Because 3 times 7 equals 21, you multiply

so that its denominator is 21. Because 3 times 7 equals 21, you multiply

by

by

:

:

.

.

Now do the same for

. Because 7 times 3 equals 21, you multiply

. Because 7 times 3 equals 21, you multiply

by

by

:

:

.

.

The subtraction problem can be rewritten as

, which you can easily solve:

, which you can easily solve:

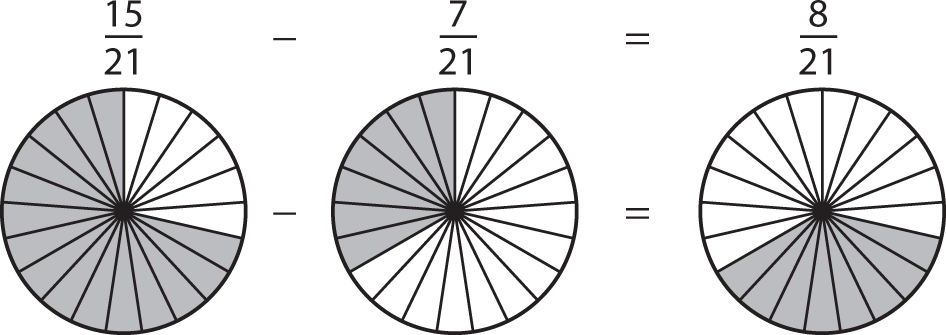

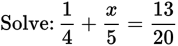

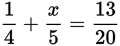

Finally, if you have a variable in the subtraction problem, nothing really changes. One way or another, you still have to find a common denominator.

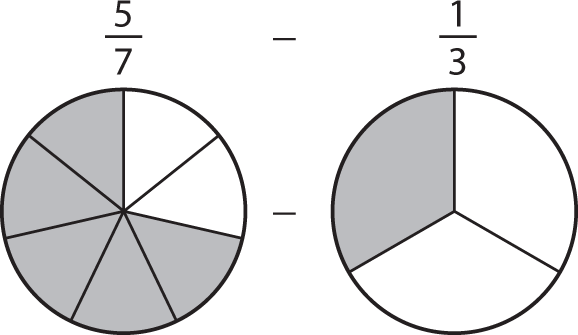

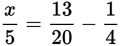

Here’s another problem:

First, subtract 1/4 from each side:

Perform the subtraction by finding the common denominator, which is 20:

So you have

.

.

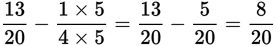

There are several options at this point. The one you should use right now is to convert to the common denominator again (which is still 20):

| Now set the numerators equal: | 4x = 8 |

| Divide by 4: | x = 2 |

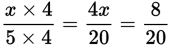

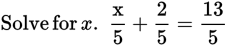

If you spot the common denominator of all three fractions at the start, you can save work:

|

|

| Convert to a common denominator of 20: |

|

| Clean up: |

|

| Set numerators equal: | 5 + 4x = 13 |

| Subtract 5: | 4x = 8 |

| Divide by 4: | x = 2 |

Evaluate the following expressions:

Suppose you were presented with this question on the GRE:

This question involves fraction addition, which you now know how to do. So begin by adding the two fractions:

.

But

.

But

isn’t one of the answer choices. Did something go wrong? No, it didn’t, but there is an important step missing.

isn’t one of the answer choices. Did something go wrong? No, it didn’t, but there is an important step missing.

The fraction

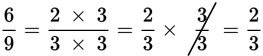

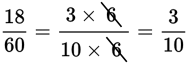

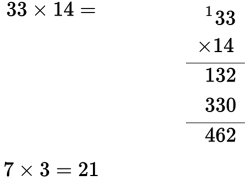

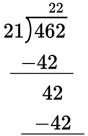

doesn’t appear as an answer choice because it isn’t simplified (in other words, reduced). To understand what that means, recall a topic that should be familiar: prime factors. Break down the numerator and denominator into prime factors:

doesn’t appear as an answer choice because it isn’t simplified (in other words, reduced). To understand what that means, recall a topic that should be familiar: prime factors. Break down the numerator and denominator into prime factors:

.

.

Notice that both the numerator and the denominator have a 3 as one of their prime factors. Because neither multiplying nor dividing by 1 changes the value of a number, you can effectively cancel the

, leaving behind only

, leaving behind only

. That is,

. That is,

.

.

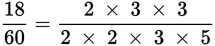

Look at another example of a fraction that can be reduced:

. Once again, begin by breaking down the numerator and denominator into their respective prime factors:

. Once again, begin by breaking down the numerator and denominator into their respective prime factors:

. This time, the numerator and the denominator have two factors in common: a 2 and a 3. Once again, split this fraction into two pieces:

. This time, the numerator and the denominator have two factors in common: a 2 and a 3. Once again, split this fraction into two pieces:

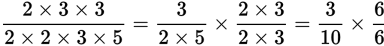

The fraction

is the same as 1, so really you have

is the same as 1, so really you have

, which leaves you with

, which leaves you with

.

.

As you practice, you should be able to simplify fractions by recognizing the largest common factor in the numerator and denominator and canceling it out. For example, you should recognize that in the fraction

both the numerator and the denominator are divisible by 6. That means you could think of the fraction as

both the numerator and the denominator are divisible by 6. That means you could think of the fraction as

.

You can then cancel out the common factors on top and bottom and simplify the fraction:

.

You can then cancel out the common factors on top and bottom and simplify the fraction:

.

.

Simplify the following fractions.

Now that you know how to add and subtract fractions, you’re ready to multiply and divide them. First up is multiplication. Consider what happens when you multiply a fraction by an integer.

Start by considering the question, what is

× 6? When you added and subtracted fractions, you were really adding and subtracting pieces of numbers. With multiplication, conceptually it is different: you start with an amount, and leave a fraction of it behind. For instance, in this example, what it’s really asking is, what is

× 6? When you added and subtracted fractions, you were really adding and subtracting pieces of numbers. With multiplication, conceptually it is different: you start with an amount, and leave a fraction of it behind. For instance, in this example, what it’s really asking is, what is

of 6? There are a few ways to conceptualize what that means.

of 6? There are a few ways to conceptualize what that means.

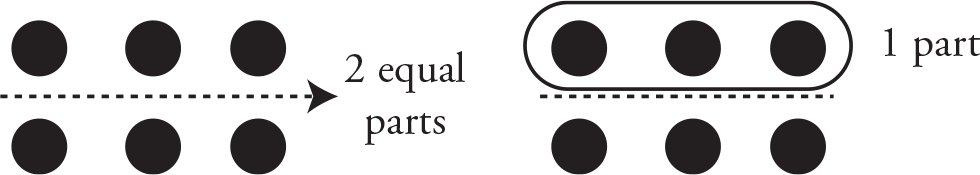

You want to find one-half of six. One way to do that is to split 6 into two equal parts and keep one of those parts.

Because the denominator of the fraction is 2, divide 6 into two equal parts of 3. Then, because the numerator is 1, keep one of those parts. So

× 6 = 3.

× 6 = 3.

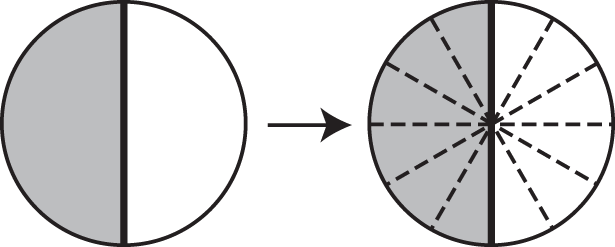

You can also think of this multiplication problem a slightly different way. Consider each unit circle of the 6. What happens if you break each of those circles into two parts, and keep one part?

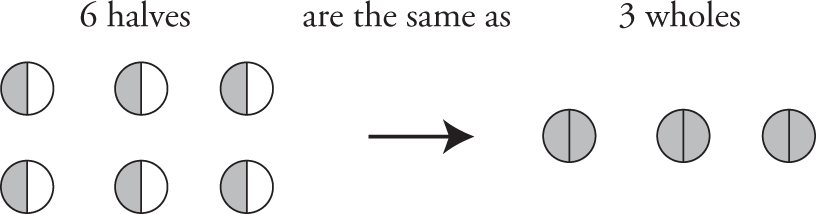

Divide every circle into two parts, and keep one out of every two parts. You end up with six halves, or

, written as a fraction. But

, written as a fraction. But

is the same as 3, so really,

is the same as 3, so really,

of 6 is 3:

of 6 is 3:

Either way you conceptualize this multiplication, you end up with the same answer. Try another example:

What is 2/3 × 12?

Once again, it’s really asking, what is

of 12? In the previous example, when you multiplied a number by

of 12? In the previous example, when you multiplied a number by

, you divided the number into two parts (as indicated by the denominator). Then you kept one of those parts (as indicated by the numerator).

, you divided the number into two parts (as indicated by the denominator). Then you kept one of those parts (as indicated by the numerator).

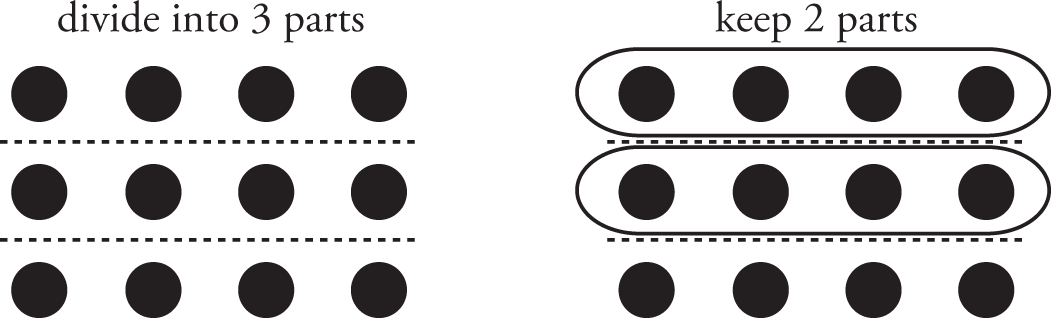

By the same logic, if you want to get

of 12, you need to divide 12 into three equal parts, because the denominator is 3. Then keep two of those parts, because the numerator is 2. As with the first example, there are several ways of conceptualizing this. One way is to divide 12 into three equal parts, and keep two of those parts:

of 12, you need to divide 12 into three equal parts, because the denominator is 3. Then keep two of those parts, because the numerator is 2. As with the first example, there are several ways of conceptualizing this. One way is to divide 12 into three equal parts, and keep two of those parts:

The number 12 is divided into three equal parts of 4, and two of those parts are kept. Because two groups of 4 is 8, then

× 12 = 8.

× 12 = 8.

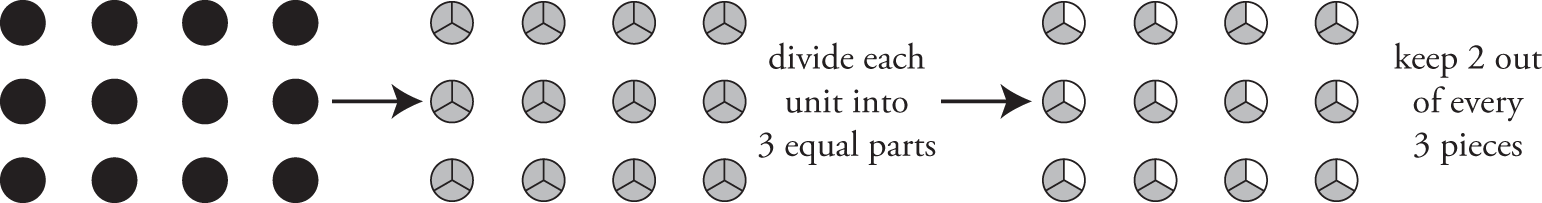

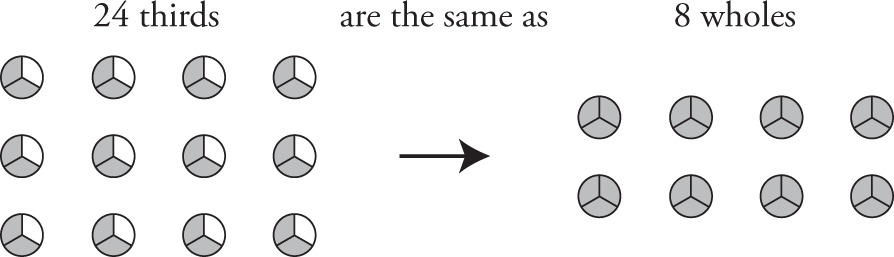

Another way to conceptualize

× 12 is to once again look at each unit of 12. If you break each unit into three pieces (because the denominator of the fraction is 3) and keep two out of every three pieces (because the numerator is 2) you end up with this:

× 12 is to once again look at each unit of 12. If you break each unit into three pieces (because the denominator of the fraction is 3) and keep two out of every three pieces (because the numerator is 2) you end up with this:

You ended up with 24 thirds, or

. But

. But

is the same as 8, so

is the same as 8, so

of 12 is 8:

of 12 is 8:

Once again, either way you think about this multiplication problem, you arrive at the same conclusion:

× 12 = 8.

× 12 = 8.

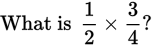

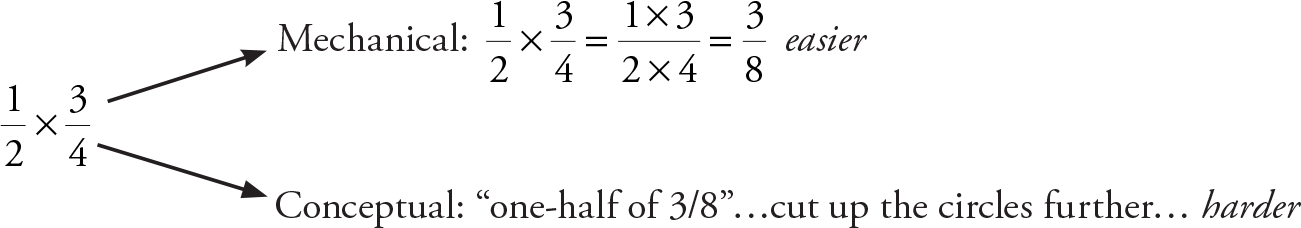

Now that you’ve seen what happens when you multiply an integer by a fraction, it’s time to multiply a fraction by a fraction. It’s important to remember that the basic logic is the same. When you multiply any number by a fraction, the denominator of the fraction tells you how many parts to divide the number into, and the numerator tells you how many of those parts to keep. Now consider how that logic applies to fractions:

This question is asking, what is

of

of

? So once again, divide

? So once again, divide

into two equal parts. This time, though, because you’re splitting a fraction, you’re going to do things a little differently. Because

into two equal parts. This time, though, because you’re splitting a fraction, you’re going to do things a little differently. Because

is a fraction, the unit circle has already broken a number into four equal pieces. So, break each of those pieces into two smaller pieces:

is a fraction, the unit circle has already broken a number into four equal pieces. So, break each of those pieces into two smaller pieces:

|

Cut each piece in half. |

Now that you’ve divided each piece into two smaller pieces, keep one from each pair of those smaller pieces:

|

Keep one out of each of the two resulting pieces. |

So what did you end up with? First of all, the result is going to remain a fraction. The original number was

. In other words, a number was broken into four parts, and you kept three of those parts. Now the number has been broken into eight pieces, not four, so the denominator is now 8. However, you still have 1 × 3 = 3 of those parts, so the numerator is still 3. So

. In other words, a number was broken into four parts, and you kept three of those parts. Now the number has been broken into eight pieces, not four, so the denominator is now 8. However, you still have 1 × 3 = 3 of those parts, so the numerator is still 3. So

of

of

is

is

.

.

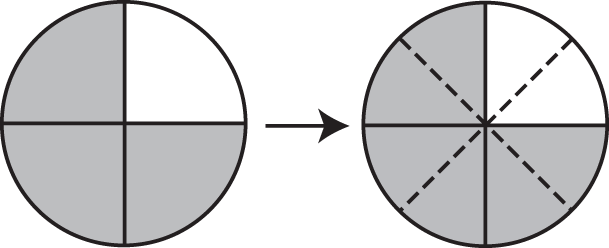

Try one more. What is

×

×

? Once again, start by dividing the fraction into six equal pieces:

? Once again, start by dividing the fraction into six equal pieces:

|

Cut each piece into six smaller pieces. |

Now keep five out of every six parts:

|

Keep five of the six. |

So what did you end up with? Now you have a number divided into 12 parts, so the denominator is 12, and you keep 1 × 5 = 5 parts, so the numerator is 5. Thus,

of

of

is

is

.

.

Multiplying fractions would get very cumbersome if you always resorted to slicing circles up into increasingly tiny pieces. So now consider, in a general way, the mechanics of multiplying a number by a fraction.

First, note the following crucial difference between two types of arithmetic operations on fractions:

Addition & Subtraction:

Only the numerator changes (once you’ve found a common denominator).

Multiplication & Division:

Both the numerator and the denominator typically change.

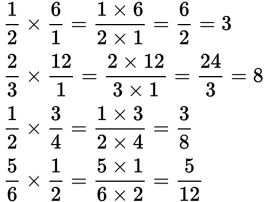

The way to generalize fraction multiplication is this: Multiply the numerators together to get the new numerator, and multiply the denominators together to get the new denominator. Then, simplify (or reduce):

In practice, when you multiply fractions, don’t worry about the conceptual foundation once you understand the mechanics:

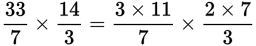

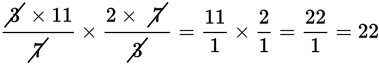

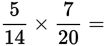

Finally, whenever you multiply fractions, always look to cancel common factors to reduce your answer without doing unnecessary work:

The long way to do this is:

You wind up with

:

:

This work can be simplified greatly by canceling parts of each fraction before multiplying. Always look for common factors in the numerator and denominator:

It’s now clear that the numerator of the first fraction has a 3 as a factor, which can be canceled out with the 3 in the denominator of the second fraction. (This is because multiplication and division operate at the same level of priority in the PEMDAS operations.) Similarly, the 7 in the denominator of the first fraction can be canceled out by the 7 in the numerator of the second fraction. By cross-canceling these factors, you can save yourself a lot of work:

Evaluate the following expressions. Simplify all fractions:

Next up is the last of the four basic arithmetic operations on fractions (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division). This section will be a little different than the other three—it will be different because you’re actually going to do fraction division by avoiding division altogether.

You can avoid division entirely because of the relationship between multiplication and division. Multiplication and division are opposite sides of the same coin. Any multiplication problem can be expressed as a division problem, and vice-versa. This is useful because, although the mechanics for multiplication are straightforward, the mechanics for division are more work and therefore more difficult. Thus, you should express every fraction division problem as a fraction multiplication problem.

Now the question becomes: how do you rephrase a division problem so that it becomes a multiplication problem? The key is reciprocals.

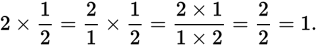

Reciprocals are numbers that, when multiplied together, equal 1. For instance,

and

and

are reciprocals, because

are reciprocals, because

Another pair of reciprocals is 2 and

, because

, because

(Once again, it is important to remember that every integer can be thought of as a fraction.)

(Once again, it is important to remember that every integer can be thought of as a fraction.)

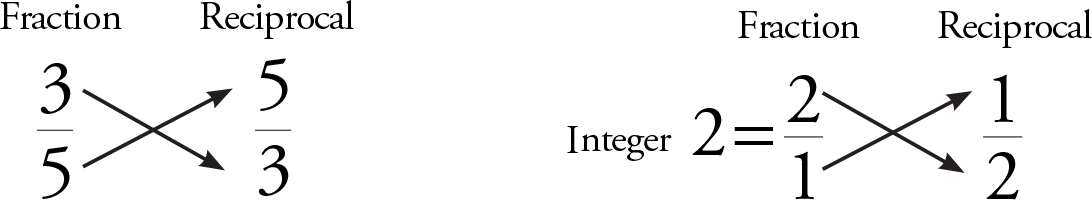

The way to find the reciprocal of a number turns out to generally be very easy—take the numerator and denominator of a number, and switch them around:

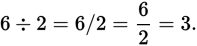

Reciprocals are important because dividing by a number is the exact same thing as multiplying by its reciprocal. Look at an example to clarify:

What is 6 ÷ 2?

This problem shouldn’t give you any trouble: 6 divided by 2 is 3. But it should also seem familiar because it’s the exact same problem you dealt with in the discussion on fraction multiplication: 6 ÷ 2 is the exact same thing as 6 ×

.

.

To change from division to multiplication, you need to do two things. First, take the divisor (the number to the right of the division sign—in other words, what you are dividing by) and replace it with its reciprocal. In this problem, 2 is the divisor, and

is the reciprocal of 2. Then, change the division sign to a multiplication sign. So 6 ÷ 2 becomes 6 ×

is the reciprocal of 2. Then, change the division sign to a multiplication sign. So 6 ÷ 2 becomes 6 ×

. Then, proceed to do the multiplication:

. Then, proceed to do the multiplication:

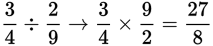

This is obviously overkill for 6 ÷ 2, but try another one. What is

÷

÷

?

?

Once again, start by taking the divisor ( ) and replacing it with its reciprocal (

) and replacing it with its reciprocal ( ). Then change the division sign to a multiplication sign. So

). Then change the division sign to a multiplication sign. So

÷

÷

is the same as

is the same as

×

×

. Now do fraction multiplication:

. Now do fraction multiplication:

Note that the fraction bar (sometimes indicated with a slash) is another way to express division. After all,

In fact, the division sign, ÷, looks like a little fraction. So if you see a “double-decker” fraction, don’t worry. It’s just one fraction divided by another fraction.

In fact, the division sign, ÷, looks like a little fraction. So if you see a “double-decker” fraction, don’t worry. It’s just one fraction divided by another fraction.

To recap:

When you are confronted with a division problem involving fractions, it is always easier to perform multiplication than division. For that reason, every fraction division problem should be rewritten as a multiplication problem.

To do so, replace the divisor with its reciprocal. To find the reciprocal of a number, you simply need to switch the numerator and denominator (e.g., 2/9 becomes 9/2).

Remember that a number multiplied by its reciprocal equals 1.

After that, switch the division symbol to a multiplication symbol, and perform fraction multiplication.

Evaluate the following expressions. Simplify all fractions.

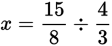

When an x appears in a fraction multiplication or division problem, you’ll use essentially the same concepts and techniques to solve:

Divide both sides by

|

|

|

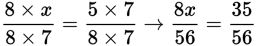

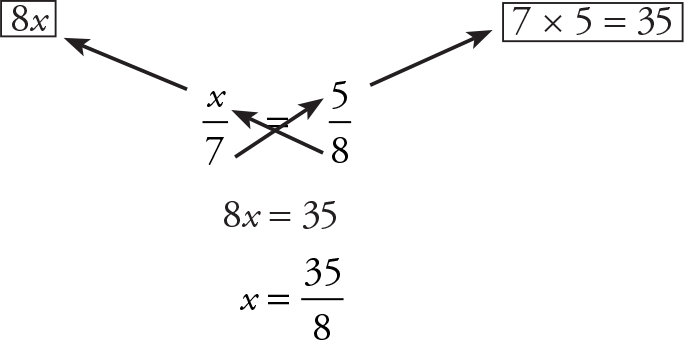

An important tool to add to your arsenal at this point is cross-multiplication. This tool comes from the principle of making common denominators.

The common denominator of 7 and 8 is 7 × 8 = 56. So you have to multiply the left fraction by

and the right fraction by

and the right fraction by

:

:

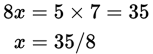

Now you can set the numerators equal:

However, in this situation you can avoid having to determine the common denominator explicitly by cross-multiplying each numerator by the other denominator and setting the products equal to each other:

When you cross-multiply, you are in fact multiplying each side by the common denominator. You’re just doing so really efficiently, without having to determine the actual value of that common denominator. Consider what happens when you multiply each side of the original equation by 56 = 7 × 8. When you multiply x/7 on the left by 56 = 7 × 8, the 7’s cancel and you’re left with 8x. Likewise, when you multiply 5/8 on the right by 56 = 7 × 8, the 8’s cancel and you’re left with = 7 × 5. By cross-multiplying, you’re already doing the right canceling, and you don’t have to figure out that 56 in the first place.

Solve for x in the following equations: