|

|

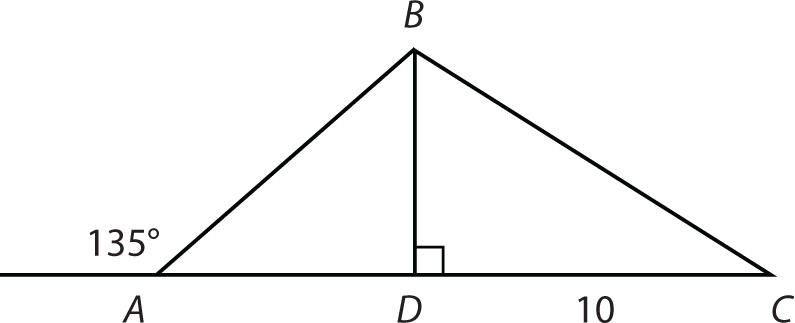

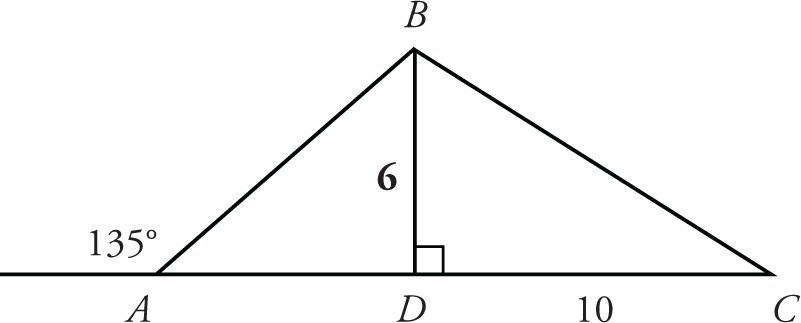

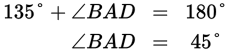

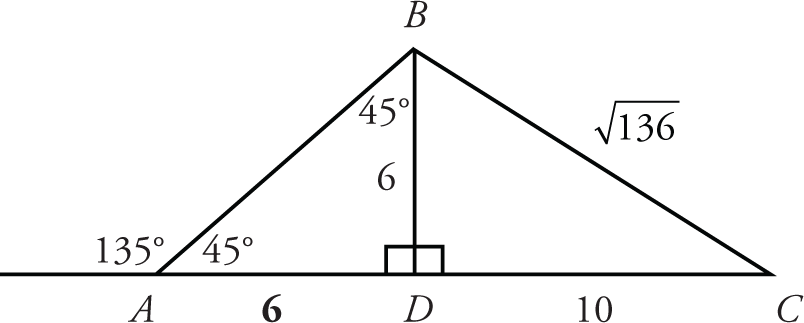

| Quantity A Area of ∆ABD |

Quantity B 18 |

The most straightforward Geometry Quantitative Comparison problems are ones in which you are given the diagram and Quantity B is a number. You can attack these with the basic three-step process outlined earlier. In most cases, you should quickly redraw the diagram you are given. Avoid the temptation simply to look and solve, because you could easily make mistakes.

On Geometry QCs, as on all QCs, there is always the possibility that you will not have enough information, resulting in a correct answer of (D). However, to arrive at the correct answer consistently, you must act as though there is enough information, while accepting that the answer may ultimately be (D). For example:

|

|

| Quantity A Area of ∆ABD |

Quantity B 18 |

For any Geometry QC problem, the first step is the same: establish what you need to know.

Quantity B is a number, so no calculations are necessary.

Quantity A is the area of triangle ABD. This is the value you need to know. For any value you need to know, there are three possible scenarios:

Approach every Geometry QC as if you will be able to find an exact value, but recognize that you won’t always be able to.

Now that you have established what you need to know, it is time to establish what you know.

To figure out what you know, use the given information to find values for previously unknown lengths and angles. You will do this by setting up equations and making inferences.

Keywords such as area, perimeter, and circumference are good indications that you can set up equations to solve for a previously unknown length. In this example, the area of triangle DBC is given. First, write the general formula for the area of a triangle, and then plug in all the known values:

The area is given as 30, and line segment DC is the base of the triangle:

Isolate h to solve for the height of the triangle:

Immediately add any new information to your diagram:

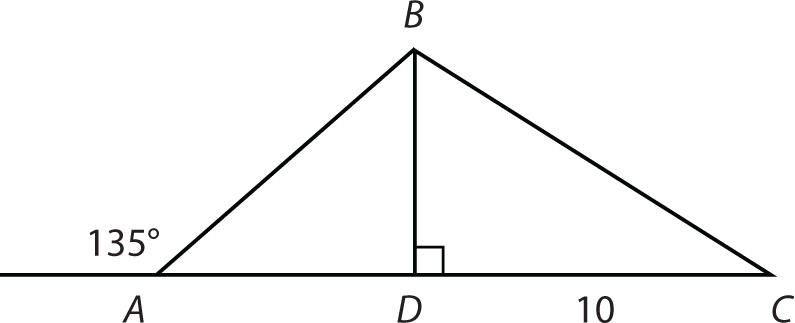

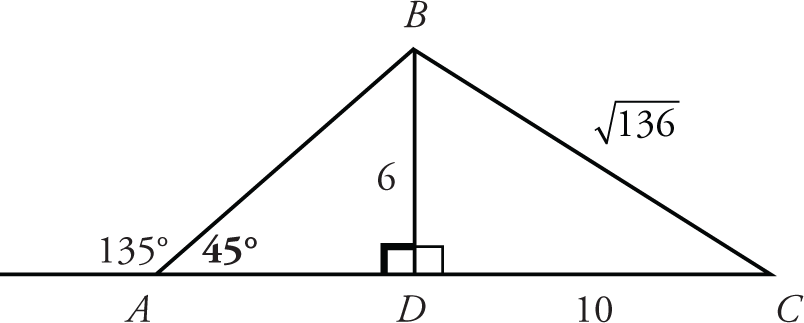

|

|

| Quantity A Area of ∆ABD |

Quantity B 18 |

Now that the length of BD is known, you could use the Pythagorean theorem to calculate the length of BC. However, keep the end in mind as you work. Knowing the length of BC won’t tell you anything about triangle ABD, so save time by focusing on other pieces of the diagram.

At this stage, no other lengths can be calculated (apart from BC). Now ask yourself, “Are there any equations I can set up to find new angles?”

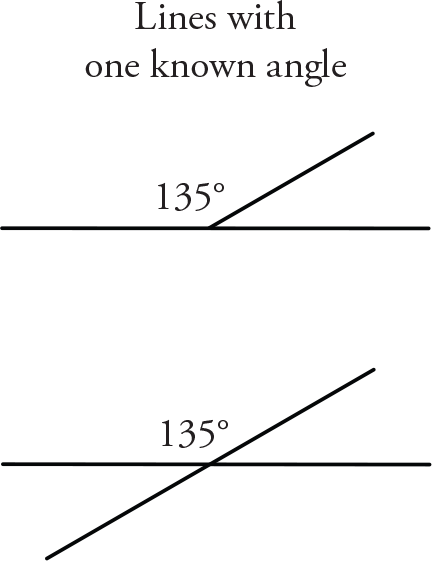

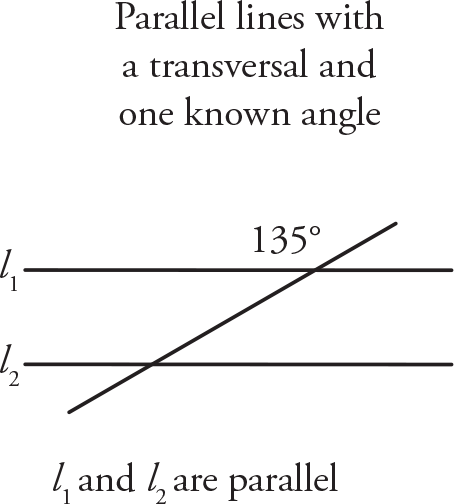

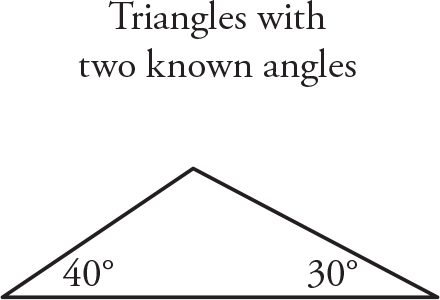

In general, you will find new angles with formulas that involve sums. Key features of diagrams include intersecting lines with one known angle, parallel lines with a transversal and one known angle, and triangles with two known angles:

|

|

|

In this diagram, you have lines with a known angle. Line segment AB divides the horizontal line into two parts. Straight lines have a degree measure of 180°, so set up an equation:

Put 45° on your copy of the diagram. Use the calculator for this sort of computation, if need be. Once you get fast, you can do the computation in your head, but you should always add it to the picture.

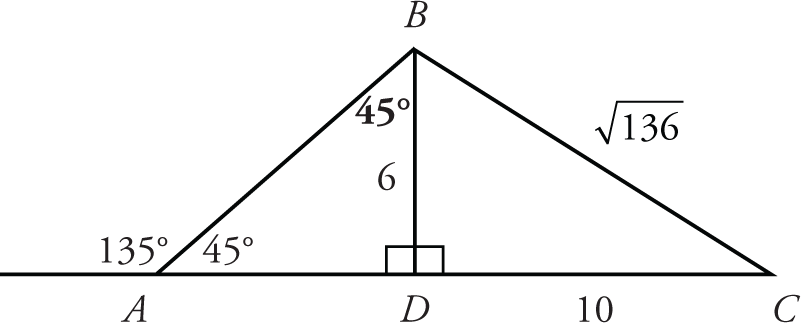

By the same logic, you also know that

|

|

| Quantity A | Quantity B |

| Area of ∆ABD | 18 |

Now two of the angles in triangle ABD are known. You can solve for the third angle:

|

|

| Quantity A | Quantity B |

| Area of ∆ABD | 18 |

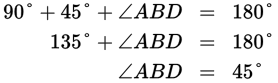

At this stage, no more equations can be set up. Another important component when solving Geometry QC problems is making inferences. Not everything you learn will come from equations. Rather, special properties of shapes and relationships between shapes will allow you to make inferences.

In this diagram, angle BAD and angle ABD both lie in triangle ABD and have a degree measure of 45°. That means that triangle ABD is isosceles, and that the sides opposite angle BAD and angle ABD are equal. Side BD has a length of 6, which means side AD also has a length of 6:

|

|

| Quantity A | Quantity B |

| Area of ∆ABD | 18 |

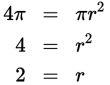

Remember that the value you need to know is the area of triangle ABD. There is now sufficient information in the diagram to find that value. AD is the base and BD is the height. Thus:

The values in the two quantities are equal and the answer is (C).

Even though you will not always be able to find the exact value of something you need to know, implicit constraints within a diagram will often provide you a range of possible values. You will need to identify this range:

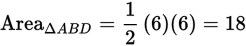

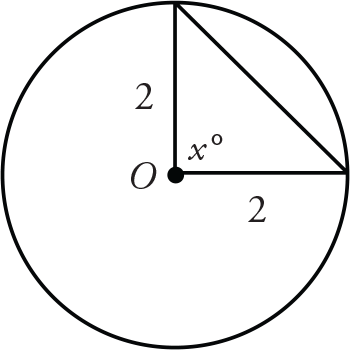

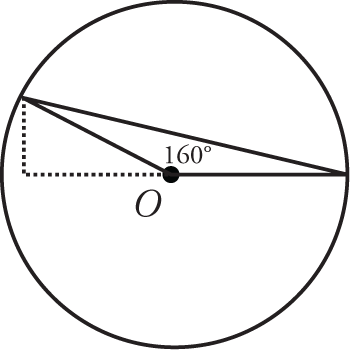

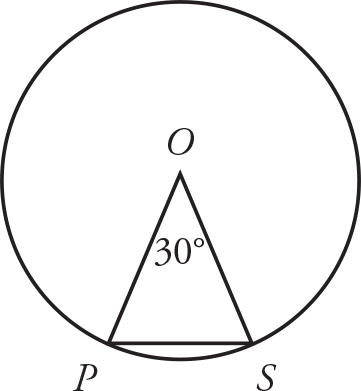

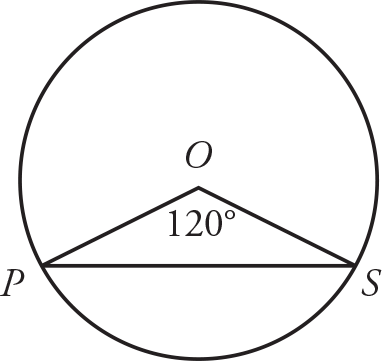

The circle with center O has an area of 4π. |

|

| Quantity A |

Quantity B |

| Area of the triangle | 1.5 |

First, establish what you need to know. To find the area of the triangle, you will need the base and the height.

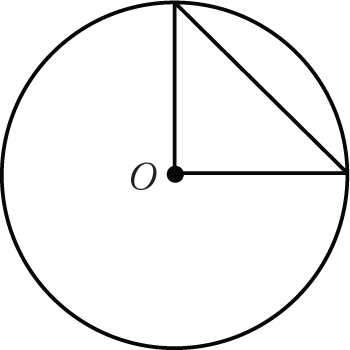

Now, establish what you know. The area of the circle is 4π, and Area = πr2, so:

The radius equals 2. Two lines in the diagram are radii. Label these radii:

The circle with center O has an area of 4π. |

|

| Quantity A | Quantity B |

| Area of the triangle | 1.5 |

Now the question becomes, “Is there enough information to find the area of the triangle?”

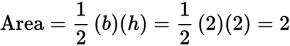

Be careful! Remember, don’t trust the picture. The triangle in the diagram appears to be a right triangle. If that were the case, then the radii could act as the base and the height of the triangle, and the area would be:

The answer would be (A). But there is one problem—the diagram does not provide any information about x.

Of course, you do know a few things about the angle. Because x is one angle in a triangle, it has an implicit range: it must be greater than 0° and less than 180°.

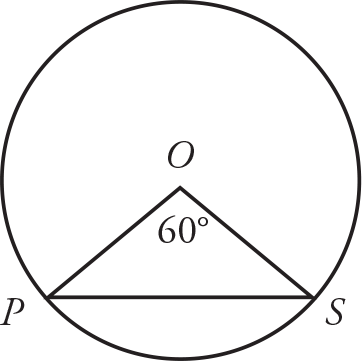

x is a value you don’t know. The question now becomes, “How do changes to x affect the area of the triangle?” To find out, take the unknown value (x) to extremes.

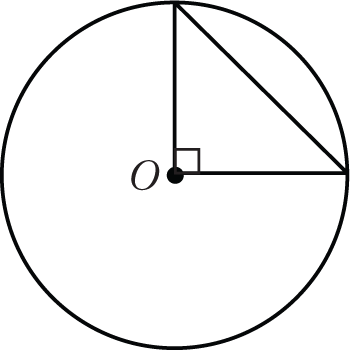

You know what the area of the triangle is when x = 90°. What happens as x increases?

|

|

|

As x increases, the height of the triangle decreases, and thus the area of the triangle decreases as well.

In fact, as x gets closer and closer to its maximum value, the height gets closer and closer to 0. As the height gets closer to 0, so does the area of the triangle.

In other words:

0 < area of triangle ≤ 2

Compare this range to Quantity B. The area of the triangle can be either greater than or less than 1.5. The correct answer is (D).

For values that you don’t know, take them to extremes and see how these changes affect the value you need to know.

This section is about some of the situations you will encounter when both quantities contain unknown values.

The basic process remains the same:

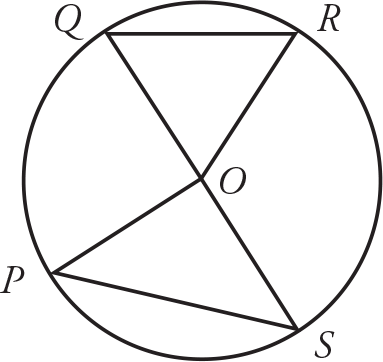

O is the center of the circle. |

|

| Quantity A | Quantity B |

| minor arc QR | minor arc PS |

The first step, establish what you need to know, is now more complicated, because there are two unknown values: Quantity A and Quantity B.

When both quantities contain an unknown, you need to know either the values in both quantities or, more likely, the relative size of the two values. For this problem, you will need to either solve for minor arcs QR and PS or determine their relative size.

Now, establish what you know. Remember: Don’t trust the picture! The way the diagram is drawn, minor arc PS appears larger than minor arc QR. That means nothing.

Actually, there is not a whole lot to know—no actual numbers have been given. OP, OQ, OR, and OS are radii, and thus have equal lengths. Other than that, the only thing you know is that

angle QOR > angle POS.

With no numbers provided in the question, finding exact values for either quantity is out of the question. But you may still be able to say something definite about their relative size.

Now, establish what you don’t know. What values in the diagram are unknown and can affect the lengths of minor arcs QR and PS ? angle QOR and angle POS fulfill both criteria. Take the values of angle QOR and angle POS to extremes.

How do changes to angle QOR and angle POS affect the lengths of minor arcs QR and PS ?

|

|

|

Note that you do not need specific angle measures in these examples—rough sketches will do.

As angle POS gets bigger, so does minor arc PS. You can assume the same relationship is true in triangle QOR.

Because OP = OQ = OR = OS, you can directly compare the two triangles. angle QOR > angle POS, which means that no matter what the values of angle QOR and angle POS actually are, minor arc QR is definitely greater than minor arc PS. The correct answer is (A).