Chapter 1

Improvement

By the end of the seventeenth century, in the wake of the Civil War and the Restoration, a new balance of political interests occupied the towns of Great Britain—not only the metropolis of London, but provincial towns as well. Even as the monarchy retained its central symbolic role and considerable effective power, the increasing strength of civil authority had its expression in the development of towns. City corporations composed of aristocratic landowners, merchants, bankers, or freemen plotted the future course of their towns with a view of the new constellation of forces that would shape the development of urban settlements in Great Britain across the course of the eighteenth century: the mercantile system of imperial might that gave new priority to roadways and ports; the industries prompting the movement and consolidation of urban populations that spurred the construction of manufactures and warehouses; the technologies of illumination, water distribution, and print communication transforming the experience of the public spaces of the city. The role of architecture changed accordingly, in both its representational and its practical dimensions. The signification of monarchy—in the major cities at least—and the church—in even the most provincial of towns—remained central elements of architectural performance, but these were joined by novel manifestations of social endeavor, such as the club or the exchange, that were instances of an emerging public domain shaped by discourse and transactions conducted in public view. In the buildings that housed these new institutions, behind the facades that fronted private interiors, and in the streets that connected them together, social life in the metropolis began to assume the now-familiar contours of modernity.

Such transformations in the towns of Great Britain, though rapid, did not occur abruptly, or decisively. Even with considerable enthusiasm for “improvements,” as they were generally known, a number of factors might act as obstacles to their realization. Theories of property, which had captured the legal and social imagination in Britain, segregated private and public domains such that physical changes to those domains might not parallel exactly the changing formulations of the civic sphere. The techniques and practices of design and construction, some long established and enforced formally by guilds or informally by habit, could constrain rather than encourage novelty. In general, improvements overlapped with prior circumstances—with older buildings, streets, and customary uses—so that the one threw the other into sharp relief. Architecture itself, a material endeavor, was in some ways less malleable than the ideas of civic space that architecture was asked to instantiate, and it was in this distinction that the role and purpose of the aesthetic register of architecture came decisively into view. In this transition from prior to future civic arrangements, the aesthetics of civic spaces began to be described in terms of beauty and ugliness, terms that—while of much older lineage and long employed in architectural discourse and poetical descriptions—served now in a particular manner to define an emerging civil constitution of towns and their society, with the concept of ugliness in particular serving to denote the uncertainties, the speculations, the difficulties of that emergence.

The Disorder of Bath

When the antiquarian William Stukeley visited the provincial city of Bath on his tour of notable sites in Great Britain, his observations conveyed a measured appreciation for some of its features tempered by a disdain for the state of its streets and buildings:

The [ground] level of the city is risen to the top of the first walls, through the negligence of the magistracy, in this and all other great towns, who suffer idle servants to throw all manner of dirt and ashes into the streets. . . . The small compass of the city has made the inhabitants croud up the streets to an unseemly and inconvenient narrowness: it is handsomely built, mostly of new stone, which is very white and good; a disgrace to the architects they have there. The cathedral is a beautiful pile, though small; the roof of stone well wrought; much imagery in front, but of a sorry taste.1

Handsomeness and beauty seem in Stukeley’s view to have resided more in the material properties of the architecture of the city than in its expressive achievement. The quality of the stone embarrassed the accomplishment of the architects who used it, and the techniques used to work the stones of the cathedral roof surpassed the artistry of the sculptures and ornaments that adorned its facade. Stukeley was aware, as most visitors would have been, that Bath was shaped by diverse intentions and by contingency as well. Its geological surroundings produced the hot springs for which the town was named, and also provided the source of the local stone that he deemed “white and good”; its governance was in the hands of a city corporation, the magistracy to whom he assigned the blame for the misbehavior of the denizens of the town; its growth over time had been constrained by the older Roman walls, producing the crowded and irregular arrangement of streets and buildings. The outward appearance of all these aspects—simply, the aesthetic effect of the city—Stukeley judged deficient, and attributed that deficiency to the architects who were “disgraced” by an admirable stone whose qualities their own inadequate efforts at design failed to complement.

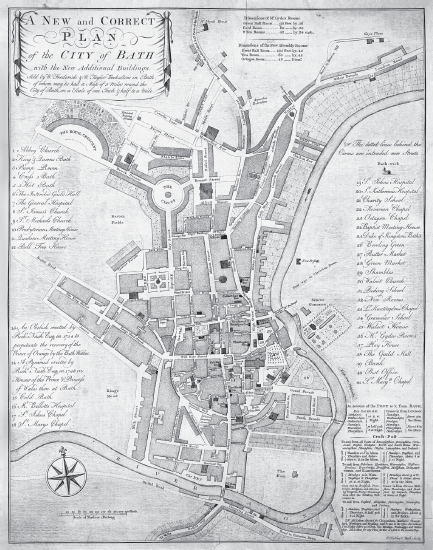

Though famous already for its medicinal baths, the city’s transformation into a storied center of leisure commenced with the start of the eighteenth century. (Figure 1) A royal visit by Queen Anne in 1702 and her return the following year brought the court and courtiers, and with them the attention and notice of other well-to-do persons who gave Bath its place on the itinerary of fashionable destinations. The town became part of the winter tour, an attraction first and most famously for its baths and their supposed curative powers, but soon also for its entertainments, its elaborate balls, gambling, and gossip. Over the span of less than two decades at the beginning of the century, Bath attained an almost unrivaled popularity, highly favored by the fashionable set for the excitement of its social scene, which in comparison to London or other settings was unguarded and permissive.2 The success of this new attraction—a leisured urbanity—was due in part to the calculated efforts of Beau Nash, who, appointed by the city corporation as the master of ceremonies in 1705, governed the social life of the town for more than fifty years.3 Wealthy visitors arriving for months-long stays came with the expectation of a enjoyable and satisfying residence. It was the job of the master of ceremonies to provide this guarantee. Nash recorded each visitor of suitable social standing as a member of “the Company,” a subscription list whose members could attend the entertainments held in the assembly rooms, be escorted to the baths, and be managed in every aspect of their social lives by the master of ceremonies.

While Nash administered the social life of the town’s visitors, the mayor and the Bath Corporation governed its citizens and its economic and material condition. The thirty members of the corporation included representatives from the many trades that composed the commercial life of the town, and their primary concern was to perpetuate its economic growth and vitality. To these fiscal ends, the corporation pursued a number of improvements, beginning with legislation such as a tax levy to pay for ten lights to be constructed in anticipation of Queen Anne’s visit, or the enactment a few years later of turnpike and paving acts to rebuild the roads leading into Bath and to pay for their upkeep. Improvements to the infrastructure of the town were accompanied by improvements to its maintenance, with further legislation ordering a regimen of street cleaning and a regular watch to protect its citizens. By 1766, the corporation had determined that new and more expansive legislation was needed in order to “have the streets etc. paved by a pound Rate, to be cleaned by a daily scavenger, and to have the power of directing all matters relative to the paving, cleansing, enlightening & watching the streets etc.”4 Such extensive concern for improvement reflected not only the foresight of corporation members who took a longer view toward the town’s future growth and vitality, but also the concern of corporation members that the town in its present state did not provide an adequate physical setting for the civic institutions and behaviors that it housed.

Figure 1. The walled medieval city of Bath occupied the roughly circular shape seen at the center of this 1776 plan. The new streets and blocks of fashionable houses expanded north and west in the eighteenth century, including elements such as Queen Square, the Circus, and the Royal Crescent, all seen in the upper left quadrant of the plan. A New and Correct Plan of the City of Bath, sold by W. Frederick and W. Taylor Booksellers (1776).

Infrastructural and managerial improvements did much to answer these two aims, but more important for the latter concern was the appearance of the town, an appearance decisively determined by its public and private buildings. The architect who seized upon this aspect of improvement and organized much of his career around it was John Wood the Elder, a precocious provincial architect who practiced extensively and influentially in Bath during the second quarter of the eighteenth century.5 In 1727, when Wood arrived in Bath and took up residence, he brought with him, by his account, designs to carry out grand transformations: “I proposed to make a grand Place of Assembly, to be called the Royal Forum of Bath; another Place, no less magnificent, for the Exhibition of Sports, to be called the Grand Circus; and a third Place, of equal State with either of the former, for the Practice of medicinal Exercises, to be called the Imperial Gymnasium of the City.”6 Any one of these would have intervened in the small compass of the town at a spectacular scale; together they would have imposed an artificial magnificence to rival cities of historical imagination. But Bath had immediate need of improvement at a much smaller and more humble scale. The quality of its houses did not match the quality of the newly arriving visitors, and its “little, dirty, dark, narrow Passages” made the perambulations of those visitors uncomfortable and at times unsafe.7

Wood was particularly appalled by the architecture of the town’s central attraction, the baths. The entry rooms of the King’s Bath “seemed more fit to fill the Bathers with the Horrors of Death, than to raise their Ideas of the Efficacy of the Hot Waters”; the Queen’s Bath was even worse, for “a Man no sooner descends into the Bath, than he finds himself sunk into a Pit of Deformity; if irregular Walls incrusted with Dirt and Nastiness, and these standing beneath irregular buildings, may be so called.”8 Wood believed that the appearance and the physical state of the baths endangered their occupants. The haphazard arrangement of forms and the decayed surfaces of the walls and floors, the darkness of the interiors and the dankness of their air, demanded, in his view, urgent remedy. The architecture of the baths was, after all, the architecture of the central civic amenity of the town, upon which its future vitality depended: “The Wretched and dangerous Condition of what made the Staple Commodity of the City I was about improving … made me lose no Opportunity, by Observation or Enquiry, to form a Design for making the Baths as Commodious as possible for the Benefit of the present Age.”9 Wood’s proposals to improve the baths were not pursued by the city corporation, but Wood had articulated the process of improvement in architectural terms and had in fact already started work on other commissions that would foreshadow the sweeping transformation of the city during the Georgian period.

A contract with the Duke of Chandos to rebuild St. John’s Hospital afforded Wood the chance to design and construct adjacent houses. Soon after, he began work on his own scheme for what would become Queen Square, four neoclassical facades facing each other across a square and unifying separate building plots behind. Constructed in what was then an open field just beyond the city wall, Wood’s design for Queen Square inaugurated a period of speculative building through which Bath expanded beyond its “small compass” and took on the more orderly and regular arrangements of neoclassical plans—straight streets, consistent proportions, and ornamentation. This architecture would properly house the Company over the course of the eighteenth century, with more commodious interiors, more elegant exteriors, and urban settings that reflected the standing of the citizens and visitors who traversed them. Wood’s notable legacy in Bath would eventually include, along with Queen Square, the King’s Circus, and the Royal Crescent, projects conceived and initiated by Wood and completed by his son, John Wood the Younger, after his father’s death in 1754. (see Figure 1) Though these works in Bath would be his most enduring, he also completed a few significant buildings outside the city, including the exchanges in Bristol and in Liverpool, which contributed to the civic improvement of those important mercantile centers.

Wood’s thirty-year career in Bath was not without conflicts—his disputes with clients arose from diverse reasons, from the architect’s tardiness to strong disagreements over the architect’s designs, and the Duke of Chandos memorably chastised Wood for his inability to properly engineer the drains: “the Water-Closets smelling so abominably whenever the Wind sets one way, ’tis a sure sign that it is the Effect of your Ignorance.”10 (Figure 2) The significance of the arc of Wood’s career lies not in the tally of successes and failures, however, but, insofar as it pertains to the issue of civic aesthetics, in the narrative of improvement along which it is structured. Wood published his lengthy and detailed account Essay towards a Description of Bath first in 1742 and in a much revised version in 1749.11 In the four parts of the book, Wood attempted to provide his reader an understanding of the city of Bath from multiple perspectives, the first part discussing the setting and environs of the town through the lens of natural science, the second giving an elaborate (and largely fanciful) story of its founding followed by a political history, the third—architectural in its focus—describing the physical qualities of the town, its buildings, and its streets, and the fourth presenting its legal and regulatory apparatus of bylaws and statutes. The composite of these four was a narrative of improvement, tempered by repeated assertions of a glorious ancient past subsequently lost, but nevertheless insistent in its demonstration of the effort by Wood and his contemporaries to realize a newly magnificent civic realm within their provincial city.

Throughout the text of his Essay, Wood provided his reader architectural indices of improvement—tiled roofs to replace thatched ones, small and ineffective glass replaced by sash windows, taller buildings, and “Ornaments to adorn the outside of them, even to Profuseness.”12 Such details had already been weighted with significance, for in the opening lines of his preface, Wood presented the transformation of Bath in explicitly architectural—and explicitly aesthetic—terms:

About the year 1727, the Boards of the Dining Rooms and most other Floors were made of a Brown Colour with soot and small Beer to hide the Dirt, as well as their own Imperfections; and if the Walls of any of the Rooms were covered with Wainscot, it was such as was mean and never Painted. . . . As the new Buildings advanced, Carpets were introduced to cover the Floors, though Laid with the finest clean Deals, or Dutch Oak Boards; the rooms were all Wainscoted and Painted in a costly and handsome manner. . . . To make a just Comparison between the publick Accommodations of Bath at this time, and one and twenty Years back, the best Chambers for Gentlemen were then just what the Garrets for Servants now are.13

Calculated in aesthetic terms, the transformation effected was an increase in beauty and a corresponding decrease in ugliness. Imperfections and dirt concealed by the brown coloration of soot and beer were unmistakable examples of a prior ugliness that was removed or rectified by more perfectly milled lumber and carpets of pleasing color. This aesthetic improvement of architectural circumstances was mirrored by a parallel improvement of social circumstances. Where in the seventeenth century “all kinds of Disorders were grown to their highest Pitch in Bath; insomuch that the Streets and publick Ways of the City were become like so many Dunghills, Slaughter-Houses, and Pig-Styes,” now Wood could point out “a handsome Pavement … with large flat Stones, for the Company to walk upon.”14 The unconstrained social habits of the earlier time slowly gave way to the social behaviors regulated by the statutes and by-laws of the town, which were in turn reflected in the well-ordered appearance of new architectural settings.

Figure 2. Detail of a letter from James Brydges, the first Duke of Chandos, to John Wood (September 24, 1728).

As they walked upon such a handsome pavement, the manner of the Company would be accordingly elegant and orderly, obedient to eleven articles of conduct agreed to by members of the Company upon subscribing to its privileges. These articles defined niceties of social etiquette, though in any given season, of course, disorderliness was as likely to be caused by fashionable members as by thieves or prostitutes. Similarly, instances of decay, meanness, or disproportion certainly persisted in the architecture of the city, old or newly built. Ugliness was not vanquished by beauty, but its valuation had taken on a particular significance that extended beyond a singular example. Wood’s intent was, unquestionably, to foster an increase in beauty, but this architectural priority reveals social specificities such as difference, lowliness, expedience, or apathy, being assigned to ugliness. Aesthetics was formulated as mode of inquiry at this same moment, and though Wood himself could not have invoked either the word or the philosophical concept, the surrounding context of British intellectual inquiry was very much concerned with questions of judgment, sensation, taste, and experience.15

The challenging question of collective judgment, of societal consensus around the evaluation of beauty or ugliness, was pursued at this time by David Hume. Examining the social manifestation of taste, Hume proposed that beauty and ugliness were not inherent properties of things, but rather were the idea or feeling produced in a person by those things. To designate a street as ugly or a building as beautiful was to describe a sentiment or a responsive emotion. Such sentiments or emotions were integral in themselves, not subject to proof or disposition outside of subjective experience. But they mirrored sensations produced by the reality of objects of experience.

When a building seems clumsy and tottering to the eye, it is ugly and disagreeable; tho’ we be fully assur’d of the solidity of the workmanship. ’Tis a kind of fear, which causes this sentiment of disapprobation; but the passion is not the same with that which we feel, when oblig’d to stand under a wall, that we really think tottering and insecure. The seeming tendencies of objects affect the mind: And the emotions they excite are of a like species with those, which proceed from the real consequences of objects, but their feeling is different. . . . The imagination adheres to the general views of things, and distinguishes the feelings they produce, from those which arise from our particular and momentary situation.16

According to Hume, sentiments had a social dimension, gathered together under a standard of taste, or a set of judgments accumulated over time by discriminating persons, not in isolation but as participants in changing social situations. Hume’s thought inflects the significance of Wood’s account of the city of Bath and of his architectural ambitions and accomplishments, for it allows an understanding of ugliness as a social judgment uncoupled from the properties of the architecture against which that judgment is registered, and reinstated instead as a social consensus of that architecture’s “seeming tendencies.” Purposeful, instrumental, bound up with intention and foresight, and as such, this consensus manifests not only architectural but also institutional and political concerns, opening the possibility of the reciprocal engagement of aesthetic properties and social consequences.

Architecture and the Neolithic Past

With the configuration of neoclassical buildings and artfully composed places like Queen Square, the North and South Parades, and the King’s Circus, John Wood the Elder supplemented the town’s rising prominence with a suitable civic appearance. Elegance achieved through the wellcrafted ornamentation of columns, window surrounds, architraves, and the like, along with consistency derived from the uniformity of the local freestone and the orthodoxy of Wood’s geometric figures, made the architecture of the town a proper setting for the affairs of the fashionable set who visited for the winter season, as well as for the ambitions of the city corporation and the wealthy merchants and tradesmen responsible for its governance. The physical appearance of the town, constituted by the material, style, and facades of its architecture, provided only part of its aesthetic value. Equally important for Wood was the representational or symbolic significance of the architecture, and this significance depended in no small measure upon its historical resonance. The historical and theoretical tradition of classical architecture was well established in Great Britain by the close of the seventeenth century. Sir Henry Wotton’s treatise on the Elements of Architecture, published in 1624, and the works of Inigo Jones and Sir Christopher Wren, along with other writings and buildings, had introduced the principles of classicism attributed to the ancient source, Vitruvius’s treatise De architectura.

Wood, however, proposed a very different lineage of architectural authority. In the spring of 1741, he published The Origin of Building; or, The Plagiarism of the Heathens Detected, a treatise of evident architectural concern, as indicated by its title, but just as much a history of cultural inheritance, in which Wood attempted to establish for architecture a divine source. The Temple of Solomon—in Wood’s day a presumptive historical reality—already served as an idealized architectural origin, but Wood aimed to make this origin more proximate to his own historical position and to displace Vitruvius from his authoritative position within architectural theorizations. The result was an account of restless imagination, tortured argumentation, and often inscrutable associational thinking. After a summary comparison of quotations from Vitruvius to sayings attributed to Moses, the author advised his reader, “we purpose, in the following Sheets … to weigh and consider, the Origin, Progress, and Perfection of Building, so as to make an Account thereof consistent with Sacred History, with the Confession of the Antients, with the Course of great Events in all Parts of the World.”17 The Origin of Building does not exclude Vitruvius, or his categorical descriptions of the architectural orders, but these appear almost as postscript, in the fifth and final book that follows the four that assertively present and justify the argument for a more ancient origin. The classical architecture of Rome and the Greek architecture that preceded it are in Wood’s view mere derivation rather than source and contained distortions and misappropriations of idealized forms and systems of design. His aim, in contrast, was to correctly align historical and aesthetic development, so that their coincidence was also the legitimation of one by the other.

In the final book, in a brief chapter, Wood took a further leap, bringing the argument of The Origin of Building closer to his time and place. Pointing to the evidence of architectural remains in Britain—“all the remarkable great Stones which lie flat on the Ground, as well as the Heaps made of several small Stones; or the single Pillars, Lines, Circles, Triangles, and Squares, composed of erect Stones”—that preceded the period of Roman occupation, Wood opened the possibility of a connection between the earliest stages of architecture and the standing stones located close by his own town of Bath.18 Three remarkable sites—Stanton Drew, Avebury, and Stonehenge—stood within a day’s ride of the town, and these remains of a lithic architecture of such “Art and infinite Labour” in Wood’s view must certainly “bespeak a Parent of more Antiquity than the Romans.”19

Wood constructed a speculative lineage for these remains in the second book of his Essay towards a Description of Bath, one based upon an elaborate and fanciful account of the founding of the city of Bath. The foundational legend of the city, which already in the eighteenth century was coming to be regarded as fable but to which Wood himself ardently subscribed, had it that the famous hot springs were first encountered by King Bladud, a Celtic prince whose disfigurement by leprosy caused him to retreat from his kingdom to live as a swineherd. After seeing his pigs wallow in the hot springs and subsequently be cured of their sores, he bathed in the water and discovered his own leprosy cured. Bladud founded a city upon this site, raising a temple with perpetual fires; centuries later the Romans raised their own temple at the site they called Aqua Sulis, and several centuries after that the medieval town developed, still centered upon the medicinal baths. With contortions of chronology and with opportunistic use of ancient and contemporary sources, Wood proposed to his readers that the inheritance of divine architecture had been brought to Britain by King Bladud himself. According to Wood’s account, Bladud had traveled to “the South Eastern Part of Europe,” where he “became a Disciple, a Collegue, and even a Master” of the philosopher Pythagoras, encountering through him the influences of Zoroaster’s Persia and the philosophical advances of Greece and conveying in return “his knowledge of the Magical Art.”20 Returning to Britain after the fall of Troy, Bladud founded a vast city with Bath as the “Metropolitan Seat of the British Druids” and a center of healing, and Stanton Drew, the “University of the British Druids,” as its center of learning.21 Wood construed the standing stones of Stanton Drew as an embodied cosmology, declaring it to be “a Model of the Pythagorean System of the Planetary World,” with its dimensions fitted to those of the Solomonic past and anchored by twin temples of the sun and the moon.22 Stonehenge was similarly a seat of learning, modeled after Stanton Drew, and therefore also descended from the divine inspiration of architecture, uncorrupted by and not indebted to Vitruvius or Roman architecture.

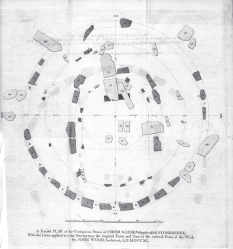

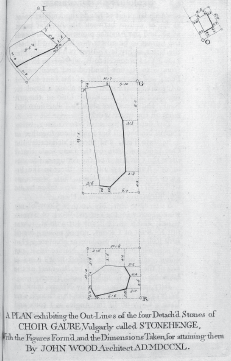

Figure 3. John Wood’s survey of the existing stones at Stonehenge with concentric circular lines showing his speculation on the original geometry of the monument. From John Wood, Choir Gaure, Vulgarly Called Stonehenge, on Salisbury Plain, Described, Restored, and Explained (Oxford: J. Leake, 1747).

The fantastical nature of Wood’s historical reasoning was sharply contrasted by the scrupulous empiricism of his study of the lithic monuments themselves. In the summer of 1740, Wood ventured his first study of the nearby antiquities, drawing sketches of the stones at Stanton Drew. These earned him the patronage of Edward Harley, second Earl of Oxford, which enabled Wood to undertake more deliberate surveys. These he carried out at the end of the same summer, first at Stanton Drew and then at Stonehenge. (Figure 3) His study of Stanton Drew was the basis for the chapters in the Essay towards a Description of Bath, while the work on Stonehenge Wood published in 1747 as Choir Gaure, Vulgarly Called Stonehenge, on Salisbury Plain, Described, Restored, and Explained. With the latter publication, Wood joined a debate over the origins and significance of the megaliths that extended from Inigo Jones’s posthumously published survey and reconstruction, which he carried out for King James I in 1620, to the contrary arguments put forward by William Stukeley in 1740.23 The axes of dispute were the authorship of the stone monuments—Roman according to Jones and Druidic according to Stukeley—and therefore their significance, pagan but imperial in Jones’s account and proto-Christian and trinitarian in Stukeley’s. Wood argued for their Druidic attribution, but with the origin of their architectural arrangement traceable, like that of Stanton Drew, to the divine architectural source of the Temple of Solomon.

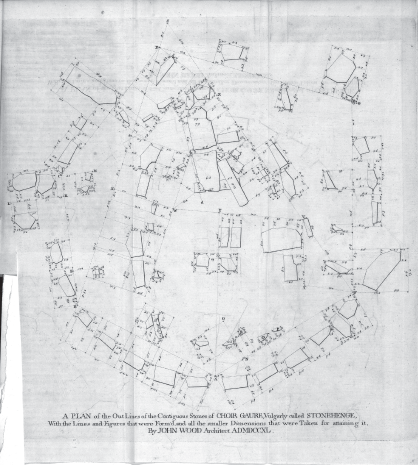

But while Wood may have found himself in agreement with some parts of the accounts offered by other interpreters, he was quite clear that none was acceptable in full: “though many have undertaken to Describe the Ruins of Stonehenge; to Restore those Ruins to their antient State; and, in general, to Explain the whole Work; Yet it is not Stonehenge that they have Described, Restored, or Explained to us, but a Work that never existed unless in their own Imaginations!”24 Wood also pointedly disagreed with Stukeley’s assertion that a minutely accurate survey of the stones was impossible, and sought to refute it with the accomplishment of his own. Though his historical interpretation remained fantastical, Wood in his measurement and survey achieved a remarked fidelity to the physical reality of Stonehenge. Over the course of a few days, Wood set survey stakes around the site in arrangements of lines and polygonal figures in order to calculate with unprecedented precision the position and orientation of the stones. (Figure 4) Over dozens of pages of his text, he rehearsed for his reader each of these survey lines and angles and noted, in additional scrupulousness, that he had left his survey stakes in place, driven down flush with the ground, should any person wish to check his measurements for error.25 The contribution of Wood’s survey lay in this precision, as it provides still a knowledge of the disposition of the site as it lay in the eighteenth century.

Figures 4 (opposite) and 5. John Wood’s illustration of his survey technique showing the rectilinear forms and measurements used to derive the outlines of the irregular stones at Stonehenge. From John Wood, Choir Gaure, Vulgarly Called Stonehenge, on Salisbury Plain, Described, Restored, and Explained (Oxford: J. Leake, 1747).

The survey’s precision has a further significance, unremarked but relevant in the context of the emergence of a civic aesthetics: Wood’s precision arose in relation to his encounter with the irregularity of the stones themselves. Not only the overall arrangement but the shapes of the individual stones were understood to be deformations from some prior, more regular state. Though Wood disputed both Jones’s and Stukeley’s overly geometric reconstructions, he too imagined a more orderly form to have been the original condition. Yet he urged his reader to understand that even the prior Stonehenge was imperfect in this regard, conceding that “Perhaps Your Lordship will be surprized at the great Irregularity which appears in almost all the Pillars of the Work,” but suggesting that an understanding of the difficulty of working such large stones set upon the ground, and of the effect of weather and vandalism over centuries changing those stones “from more regular Forms into the Shapes we now see them, it will very much abate our Ideas of Irregularity in the present Position of them.”26 In an illustration of his technique for accurately ascertaining the profile of the stones, Wood shows the stones placed within rectangular frames, which he marked at the site with survey stakes and used as a norm to measure the offset dimensions of the existing stone. (Figure 5) This illustration evokes the erosion of the surfaces over time while also establishing a theoretical proximity of the regular and the irregular. Not simply the original state of the stone in contrast to its present condition, but a simultaneous proximity, in Wood’s perspective, of an irregularity that is contained by and within a regularity; in more directly aesthetic terms, an ugliness encased within beauty.

“The Body of Stonehenge, thus Restored to its perfect State, cant be conceived otherwise than as a most Beautiful, as well as a most Magnificent Structure.”27 For Wood, as for Jones and Stukeley, the aesthetic presence of Stonehenge in its ruined state was a physical index for a prior presence that could be resummoned only through imagination and through techniques of representation. Wood disagreed with the others as to the arrangement and form of this prior presence, proposing a much less elaborate geometry to resolve the evidence of the stones as he found them into a coherent pattern of concentric rings. His restoration differs not only in its form but, most decisively, in Wood’s accompanying claim that his plan of Stonehenge in its perfect state represents the “State intended by the Architect of the Work” even though the monument was never actually realized in this form.28 The “Design was so far from being compleated, that I have many reasons to think the first Builders of Stonehenge did not Perfect so much as any one single part of the whole Fabrick,” argued Wood, attributing the incompleteness of the monument not to contingency or accident, but proposing instead that it had been “purposely left unfinished.”29 For Wood, then, Stonehenge existed in three states: the one he encountered during his survey; the ideal one planned by its architect; and a third, incomplete state between these two. It is Wood’s capacity to conceive of incompleteness as a positive condition that issues the most radical insight into the aesthetic presence of Stonehenge, for this conception collapses the otherwise sharp distinction between perfected form and ruined condition. Though Wood himself did not use the word “ugliness,” it is implicitly framed through his argument, not attached to the deformity of the ruin as a negation of beauty, but instead possessed of an instrumental, deliberate capacity, in the willful incompleteness of Stonehenge.

Wood arrived at his threefold view of Stonehenge only through the unique composite of an unconstrained historical imagination and a highly constrained technique of representation. It was through Wood’s encounter with Stonehenge as a reality that a framework for ugliness came into view. Wood’s conclusions were conditioned by the materiality and the actuality of the stones: their size, their weight, their surfaces. The irregularity of their abraded surfaces was made comprehensible, calculable, and representable by Wood’s survey points, lines, and measures. Wood’s undertaking to imagine the actual process used for the almost unimaginable labor of lifting the immense stones into place led him toward his reflections on incompleteness. His contemplation of the aesthetics of the stones was based not just upon a painterly view of Stonehenge in its setting, but also, and seemingly more, upon a close if speculative analysis of the color, crystallization, and geologic source of the stones.30 The sum of these different grapplings with the lithic actuality of Stonehenge was a representation that attempted to contain the excessive reality of the monument, an excessive reality that would itself be characteristic of an emerging conception of ugliness. With its careful study of the irregularity of the stones, and the decision to think historically about incompleteness, Wood’s investigation of Stonehenge introduced a substantively novel perspective on what would be two other constitutive dimensions of the aesthetic of ugliness: irregularity and incompleteness. Though the eccentricity of his theories often prompts their segregation, this novel perspective was not unrelated to the social and civic intentions of Wood’s own architectural work, for the aim of his historical efforts was to establish and legitimate a British origin to which that work might be bound. In fashioning a conceptual understanding of irregularity, incompleteness, and implacable materiality, Wood fashioned also a framework for the coexistence of ugliness and civic aesthetics.

The Stones of Bath

The opening chapters of the Essay towards a Description of Bath demonstrated both Wood’s interest in the local geology and that his knowledge of it was current with recent scientific thinking: “Experience hath sufficiently demonstrated that the Body of the City of Bath stands upon a hard Clay and Marl, of a bluish Colour, with Stratas of Rock,” while under the soil of the vales outside the city walls, “the Stratas of Rock intermixed with the Clay and Marl soon become a kind of Marble, called Lyas; … These Rocks increase in their Progress westward; and the Beds of Gravel, as well as the Veins of Coal, increase likewise; the latter to such a high Degree, that large Quantities are now raised and sold within three Miles of the hot Fountains in the Heart of the City.”31 These seams of coal, then beginning to assume their commanding economic importance, were not the only mineral resource of specific economic value; for an architect like Wood, the strata nearby the town contained a more vital resource—freestone. A type of limestone, freestone was a desirable building material because it could be cut in any direction and therefore used for architectural profiles or details, and it was admired also for the color and texture of its surfaces; the aesthetic quality of the stone, in other words, lay both in its visual appearance and in the shapes into which it could be contrived.

The local freestone, also known as Bath stone, would become familiar as the typical architectural surface of Georgian Bath, but the stone was little used in London, due in large part to the protectionism of local masons and architects in the metropolis who denigrated its appearance and durability. Wood and his compatriots actively fostered its recognition, with Wood trying to convince the Duke of Chandos to use the stone for a new house in London.32 On another occasion, his advocacy was more public and more cunning, as Wood recounted in boastful anecdote: “The Introduction of the Free Stone into London met with great Opposition; some of the Opponents maliciously comparing it to Cheshire Cheese, liable to breed Maggots that would soon Devour it; and the late Mr. Colen Campbell, as Architect, together with the late Messeurs Hawksmoor and James … were so prejudiced against it … they Represented it as a Material unable to bear any Weight, of a Coarse Texture, bad Colour, and almost as Dear as Portland Stone for a Publick Work in or near London.”33 Wood intervened, attending a public meeting for the selection of stone for Greenwich Hospital and having a mason provide samples of Bath stone and Portland stone; Campbell, strong critic of Bath stone, promptly mistook the one for the other, exposing his partiality and also demonstrating the high aesthetic and material quality of the stone from Bath.

Ralph Allen, a prominent civic leader and entrepreneur who had a near monopoly on local quarries in Bath, chose to make his new estate an architectural display of the quality of Bath stone. Wood produced several designs “wherein the Orders of Architecture were to shine forth in all their glory,” before Allen settled on what they deemed a more humble approach. The humility is relative, for the building executed over a number of years, including periods of estrangement between Wood and Allen, was a commanding neo-Palladian structure of considerable scale and elegance. While work proceeded on the house, the grounds of Prior Park, as the estate was named, were embellished by a garden laid out by Alexander Pope, an acquaintance of Allen who was then elaborating the aesthetic principles of naturalistic landscapes and poetical allusion that would develop into the picturesque movement. (Figure 6) The house faced a lawn perspectivally framed upon its central axis, but to one side Pope designed a wilderness of woods, paths, watercourses, and poetic elements such as a grotto of rustic stone. The very aspects that Wood had reckoned with at Stonehenge, irregularity, incompleteness, and material presence, Pope employed as attributes of aesthetic purpose.34 Prior Park was further embellished by a very different kind of feature—a railway that connected Allen’s stone quarries, located just beyond the estate, with warehouses and docks on the river Avon from which the stone could be delivered to Bath or other sites by barge. The system possessed an ingenious simplicity: carriages filled with stone could be guided down from the quarry holding large cut blocks or pieces of rubble stone; gravity powered the descent, controlled by a braking mechanism, and the empty carriages were drawn back to the quarry by horses.

Figure 6. An engraving of Prior Park shows Alexander Pope’s forest wilderness, containing the grotto, between the house and the railway featured prominently at lower right. Anthony Walker, Prior Park, the Seat of Ralph Allen Esq. near Bath / Prior Parc, la Residence de Raoul Allen Ecuyer pres le Bath (1752).

The means devised by Allen to deliver stone from his quarries to his warehouses had an economic expedience, but also had a decisive role in the constitution of the civic aesthetic that Wood sought to introduce into Bath. When Wood began his career there, he found that the local masons adhered to a peculiar sequence of work. After blocks of stone were raised out of the neighboring quarries, they were worked by masons designated free masons, who were entitled to carve the freestone into the dressed blocks that would be used as architectural facings. These dressed stones were transported from the quarry into the city and there set into place by rough masons, the masons who worked rubble and common stones and who were entitled to raise walls at the building site. Wood criticized this organization of work for its deleterious effects upon the resulting architecture. Because of the cumbersome and incautious transportation required to bring already finished blocks to the building site, the “sharp Edges and Corners of the Stones are generally broke” by the time they are delivered; and thus the architectural works of Bath “lose that Neatness in the Joints between the Stones, and that Sharpness in the Edges of the Mouldings, which they ought to have; and which People, accustomed to good Work in other Places, first look for here.”35 The civic character of Bath, dependent for its expression upon the precision and sharp delineations of form and ornamentation in its architecture, had been compromised by the customary processes of quarry work and masonry. Allen’s railway alleviated this problem: masons could be stationed in the warehouses by the river or at the quarry, allowing for a different distribution of work upon the stones, and dressed or unfinished blocks could be delivered with greater facility and less chance of damage due to the less rugged mode of transport. (Figure 7) In addition, Wood claimed credit for introducing the use of “the Lever, the Pulley, and the Windlass” by masons on building sites in Bath. Before he recruited laborers from other parts of Britain familiar with such contrivances, the locals had “made use of no other Method to hoist up their heavy Stones, than that of dragging them up, with small Ropes, against the sides of a Ladder,” with all the consequential damage that entailed.36

The necessity of technologies such as the railway or cranes at his building sites was the provision of more precise translation of stones from their place of origin underground to their destinations aboveground in the civic apparatus of architecture that Wood was projecting for Bath. Wood’s concern for the correlation of the material of architecture with its aesthetic consequences was not merely pragmatic, not only an attention to construction or physical appearance, but a speculation upon symbolic dimensions as well. One of the early chapters of the Essay towards a Description of Bath confirms this emphasis, with a passage in which Wood offers a seemingly digressive description of a local coal-works:

The Hovel for working one of the Pits is exceedingly remarkable, as it lately represented a covered Monopterick Temple, with a Porticoe before it. The former shelters the Windlass, the latter sheltered the Mouth of the Pit; and one was raised upon a Quadrangular Basis, while the other appears elevated upon a circular Foundation; a Figure naturally described by the Revolution of the Windlass.

The Diameter of this Figure is just four and thirty Feet, and the Periphery is composed of six and twenty insulate Posts, of about seven Feet six Inches high, sustaining a Conical Roof terminating in a Point and covered with Thatch: Mere Accident produced the whole Structure; and if the Convenience for which it was built was of a more eminent Kind, the Edifice would most undoubtedly excite the Curiosity of Multitudes to go to the Place where it stands to view and admire it … as a Structure of the same Kind with the Delphick Temple after it was covered with a spherical Roof by Theodorus, the Phocean Architect.37

Wood included no illustration, but the structure he described was not uncommon above the pitheads that were appearing in increasing numbers in Somerset. In its simple form, this structure would have had a windlass, a raised circular drum turned by horsepower to wind and unwind a rope, next to a wooden framework with mounted pulleys guiding the hoisting rope down and up the mineshaft to the caverns below. The structure that Wood described was more elaborate: the windlass was sheltered by a thatched roof conical in form and supported by twenty-six columns; the mouth of the pit was “sheltered,” implying a roof and substantial supports. Though Wood conceded that the appearance of the structure resulted from “mere accident,” he asked his reader to see this mechanical device as housed not in a “hovel,” but in a monopteric temple with a portico, as grand in its architectural presence as the temple at Delphi.

Figure 7. Masonry and architectural details rendered in Bath stone in the buildings of the King’s Circus.

Wood’s moment of architectural contemplation, insignificant in the larger narrative of Essay towards a Description of Bath and therefore overlooked in assessments of that text, brings into view two aspects of his architectural work that bear upon questions of civic aesthetics. The first of these, straightforwardly enough, is the attention that Wood paid to the geological surroundings of the town that he aimed to improve, surroundings upon which the materiality and therefore the aesthetics of his architecture directly depended. The second is Wood’s preoccupation with the devising and codification of a civic architecture, that is, an architecture of collective purpose that represented and encouraged the activities and discourse of communities of citizens. Such an architecture did not consist only of the traditional symbols of monarchy, state, or church. In the same years Wood surveyed neolithic monuments and assembled his history of the origins of architecture, he designed and built the Bristol Exchange, itself a monument to the mercantile importance of that city.38 In the description of the coal-works, Wood conjured an appropriately civic architecture for an economic engine that did not yet have an adequate architectural representation. The expedient assembly that sheltered the windlass and pulley was mere hovel, but the working of the coal seam below was an activity of economic importance that merited a far more deliberate and accomplished architecture; in short, a civic aesthetics.

Ugliness and the Citizen

The complexity of architectural ugliness in the emerging formulations of civic aesthetics consisted of the changeable valences of the social and aesthetic valuation of ugliness. Wood’s efforts to refute the degraded reputation of Bath stone and to secure a means for its use free of imperfections, along with his campaign to improve and rectify the disorderly and decayed state of the town, point to a desire to elide the instances of architectural ugliness. Certainly, Wood aimed to bring beauty into existence, but Wood’s other contributions to architectural thinking raise different perspectives, concerned less with the undecidability of ugliness than with the possibility that architectural ugliness had (and would continue to have) a social function. This function may be the effect of a single building, but Wood’s architectural productions—drawings, buildings, writings, managements—suggest that elements of architectural ugliness participate in more diffuse or more distributed ways as well. The presence, in Wood’s professional work, of stones as historical markers and stones as economic instruments indicates this social distribution. His survey and analysis of Stonehenge not only accounted for but assigned merit to two characteristics—irregularity and incompleteness—that were, in parallel contexts of his work, factors of ugliness. To the material aspect of social function, Wood’s life adds a further factor, that of personification, or the role of the person within the social distribution of architectural ugliness. The many idiosyncrasies of John Wood the Elder do much to suggest the importance of embodiment, but it was actually the son to whom he gave his architectural legacy, John Wood the Younger, who participated in a most curious and telling social context: the Ugly Face Club of Liverpool.

In 1751, while supervising the construction of the Liverpool Exchange on behalf of his father, Wood the Younger joined a social club that gathered together men purported to be of unfavorable visage. (Figure 8) This “Honorable and Facetious Society of Ugly Faces” was undoubtedly premised upon the conviviality of its fortnightly meetings, and did not advance any aim other than congenial fellowship. Nevertheless, it maintained clearly stated standards of admission for any prospective member, who would have to possess “something odd, remarkable, Drol or out of the way in his Phiz, as in the length, breadth, narrowness, or in his complexion, the cast of his eyes, or make of his mouth, lips, chin, &c.”39 Other bodily features, regardless of whether they would be regarded as deformities, were not to be taken into consideration. Only the face of the candidate was subject to judgment, and certain of its attributes could be viewed preferentially. For example, “a large Mouth, thin Jaws, Blubber Lips, little goggyling or squinting Eyes [were] esteemed considerable qualifications in a candidate,” as was a “large Carbuncle Potatoe Nose.”40 The membership at one point voted to purchase five pictures of ugly faces, presumably to give some emphasis to the decor of the rooms in which they met and some objective standing to the issue around which they organized themselves.

Figure 8. Advertisement for the Ugly Face Club of Liverpool on the occasion of an anniversary in 1806.

By the time Wood the Younger was elected to membership in 1751, the Ugly Face Club had been in existence for at least eight years, with departing members clearly being replaced by others eager to join. Surprising though it may now seem, the club was not all that unusual and was by no means the first of its kind. Forty years earlier, the Spectator claimed to have received a letter giving notice of the existence of an “ill-favoured Fraternity” at Oxford that had “assumed the name of the Ugly Club.”41 An ensuing exchange of letters over several issues extended an offer— which was accepted—for the Spectator to join as a member, as well as an assertion from another correspondent that priority of invention ought to be given to a “Club Of Ugly Faces [that] was instituted originally at Cambridge in the merry Reign of King Charles II.”42 Though these earlier clubs may or may not have existed, the idea of ugly clubs certainly existed by the beginning of the eighteenth century, among the innumerable social clubs, large and small, that had sprung into existence over the preceding decades. The phenomenon of the social club—a gathering of men with shared interest, profession, or conviction for the purpose of fellowship and discourse—arose following the Restoration with institutions such as the Civil Club.43 During the eighteenth century, these clubs became vital venues for a new type of participation in public life that could be pursued by men (and some women) in a variety of professions and social stations. They were spaces of conversation and debate, spaces of collective attention.

Though the Ugly Face Club of Liverpool was only one of many hundreds of clubs, it would have been one of the few to focus its membership upon an aesthetic particular: ugliness. The evidence for the club’s existence is a nineteenth-century reprint of its minute books for a ten-year period, but the only evidence of the purported ugliness of its members would lie in the lists of members’ names and qualifications contained in those minutes. All of these textual descriptions, following the facetious intention of the club itself, attempted short but lurid accounts of each member’s features, with the record for Wood the Younger, entered on July 22, 1751, giving special attention to his profession: “A stone colour’d Complexion. A Dimple in his Attick Story. The Pillasters of his face fluted, Tortoise ey’d, a prominent Nose, Wild Grin, and face altogether resembling a badger, and finer tho’ smaller, than Sir Chris’hr Wren or Inego Jones’s.”44 The equation between architecture and the appearance of the body was already deeply embedded in architectural discourse, and its repetition here would have been unremarkable but for the fact that its application was to testify to ugliness and that it was not proof of ugliness but rather the instrument by which ugliness could be measured. The lines are brief (though they would seem to have been given more thought than those describing other members) and can carry only the burden of suggestion. But they do indeed suggest the role that architecture might be conceived to perform: not to be ugly but to enable the definition of ugliness toward particular ends.

In the case of the Ugly Face Club, that end is a collectivity of social experience, which was the purpose of the club itself. It was one element within the larger constellation of institutions, habits, and enterprises that made up the emerging modern civic sphere. In important mercantile cities like Liverpool and Bristol, or in a provincial town such as Bath, the elements of civic life were being fitted together with architectural settings such as the two Exchanges, or the Square and Parades in Bath. The Ugly Face Club, and Wood the Younger’s place and characterization within it, supply a way to conceptualize the role of ugliness that will be pursued in the successive episodes of this book. It endows the aesthetic with a purposeful rather than reflective position; in other words, the aesthetic describes not the encounter with an object of contemplation but the performance of a social role. In this sense, ugliness contains a deliberateness, an intention, or a cause outside of itself. Though the visages of the club’s members are natural endowments, they are made ugly through the bylaws and minute records of the club, through institutional protocols that assign the authority and standards of judgment. This type of ugliness acts as a public attribute, in that it is judged and remarked in a collective setting, here a convivial social exchange but more generally as a mode of exchange between the participants, individual or institutional, of civic life. Understood in this light, ugliness possesses an instrumentality, a capacity to enter into and to affect the routines of society.

The episodes in the chapters that follow have metropolitan London rather than provincial Bath as their setting, and manifestations of collective endeavor and a civic realm are correspondingly less narrowly defined. They are decisively present nonetheless, as are the instrumental mediations of the aesthetic revealed in the four sections of this account of Wood: the social, the historical, the economic, and the civic. The very strangeness of John Wood the Elder’s efforts to forge a public architecture in Bath, and also the fascinating strangeness of Wood himself, thus bring into view a broader and more complex conception of the ugly than one delimited by questions of style and taste. Though both style and taste enter into the conception of ugliness, they are not the decisive mechanisms of judgment as ugliness becomes entangled with the speculations upon distant history, the management of building materials, or the reformation of social behaviors. In the work and writing of John Wood the Elder, one can find the example and evidence of the new significance of architectural ugliness in eighteenth-century Britain as, in architectural stones and in architectural personae, ugliness emerged as an instrument of political and social transformation.