Chapter 3

Irritation

On January 15, 1959, a procession of a few dozen mourners appropriately clad in funereal clothing made its way along Lombard Street in London. Pallbearers, led by a woman holding a floral wreath, carried a coffin upon their shoulders. The coffin was empty, but not silent—it bore an inscription saying “RIP Here Lyeth British Architecture.” The wreath, too, offered a remembrance, though not of a past architecture but of an architecture not yet built, with a text and a photograph identifying the deceased as the new headquarters building for Barclays Bank, whose cornerstone was to be laid that very day. (Figure 15) Having arrived at the site of the new building where the stone-laying ceremony was shortly to take place, the mourners laid the coffin upon the pavement and, with suitable sobriety, placed flowers upon its top. Eulogies followed, though these in perhaps somewhat less ritual form, because the funeral itself was a statement of protest. One mourner proclaimed that the proposed Barclays building was “abysmally ugly, little better than a stone slab in a mortuary”; another carried a sign that declared “The City Is Ugly Enough Already.”1

A funeral is a manifestation of collective affect. The gathered mourners all have their individual emotions, their degrees of sorrow, regret, or relief; but together they represent grief, an inarticulable feeling that in being reflected between the mourners becomes the collective affect of a funeral. The ritualized elements of the funeral, such as black clothes, wreathes of flowers, the procession of the coffin, and words of remembrance, are the representational elements of this affect that give it a material presentation, that evidence its existence. Even a mock funeral such as the one that proceeded along Lombard Street achieves the semblance of collective affect by answering the expectation of representational elements. The affect of the mock funeral would have been a semblance insofar as the mourners did not actually experience the shared disorientation of grief or individual emotions of sorrow, but its potential for collective affect persisted nevertheless because some expression was being made and directed toward an object as a shared judgment.

Figure 15. Lombard Street in the City of London, with the Barclays Bank headquarters building on the right.

The mourners gathered in January 1959 were members of Anti-Ugly Action, a group founded a few months earlier by students at the Royal College of Art to protest what they saw as a prevailing mediocrity in new architecture in London and Britain more generally.2 The funeral procession was the group’s third “operation” directed at a recently completed or newly planned commercial building. Each operation was conducted as an affective performance. The first operation, for example, included banners, a bugler, and a drummer, and slogans chalked upon the sidewalk in front of a series of offending buildings, and the fourth operation would make use of eighteenth-century costumes to mock traditionalist architecture. In the procession down Lombard Street, the ceremonial interment of architecture conveyed the obvious expression of decline and decay, while also providing a theatrical counterpoint to the official ceremony of the laying of the cornerstone, which was wittily recast as a tombstone. The group’s mocking performance had a serious motive, however, which was to direct a critique broad enough to indict a generality of architecture, rather than just a few specific buildings. The self-designation as Anti-Ugly drew an equation between ugliness and a level of mediocrity, of poor quality, that according to the group was not contingent upon style. While it is evident that members of the group advocated for modernist architecture—placing emphasis upon the belief that architecture must reflect its contemporary moment—they insisted that theirs was not a critique premised upon presumptions about stylistic propriety.

The boom of postwar building through the 1950s produced a transformation of the fabric of British cities. In London, the scale, the facades, and the material of new office blocks, many of them speculative buildings, altered the experience of the citizens walking and working in the city. While many of these buildings were vouchsafed by their architects and their owners in terms of modernist principles of function, cost, and technological advancement, the members of Anti-Ugly Action set different terms for their critique. Theirs was an unabashedly aesthetic critique, rather than a moral or material one. It was the appearance of these buildings, their outward appearance from the street, that was at issue, and not, they said, predetermined objections over style. In other words, though the Barclays Bank headquarters might have been singled out for the disproportion of its neoclassical dress, with the enormous scale of the building crudely attenuating its smaller details along Lombard Street, a bad modern building would be subject equally to anti-ugly sentiment as a bad traditionalist building such as the one they had ironically interred. Whether or not the members of Anti-Ugly Action fully achieved this agnosticism, their protests did articulate their judgment explicitly in terms of quality rather than in always-prevalent terms of style.

The new constitution of quality as a measure for the judgment of ugliness had a particular implication: it oriented the group’s aesthetic advocacy toward an attention to average rather than exception. The buildings singled out for protest were only specific elements within a broader class that Anti-Ugly Action derided as “architectural stodge.”3 By marking out that class in such a fashion—as stodge—Anti-Ugly Action bridged from the particularities of style to the generality of quality and opened the possibility of speaking of a widespread standard of architecture in postwar Britain. The architectural critic Ian Nairn (who addressed the members of Anti-Ugly Action in a lecture just after the group was founded) described Bowater House, a commercial development alongside Hyde Park that Anti-Ugly Action had approved, in telling terms: “A curate’s Egg. Walls with a good deal of trouble taken over the materials and proportion, yet a roofline (not entirely the architect’s) which is laissez-faire at its worst. A hulking shape from the park, yet an exciting experience to walk under. . . . This perhaps should be the average. Alas, it is far above it.”4 In other words, a building with some merit, but nevertheless quite mediocre. This level of architectural accomplishment, according to Nairn, could be acceptable as an “average” standard.

The broader concept of an average, invoked colloquially by Nairn in 1964, had already gained a well-established pedigree in social representations from the nineteenth century onward.5 The rise of statistical information and its acceptance as an accurate rendition of the vast contingencies of social life made it possible to define a seemingly coherent norm out of a collection of differentiated points of data. Crime, physiology, prices, disease, income, weather—any such collation of facts might be sorted and graphed to bring into view frequencies and regularities, to define the average. A current of visualization and visual assessment ran through many of these processes, as Audrey Jaffe has suggested: “Nineteenth-century strategies of quantification and measurement often arranged diverse natural and social phenomena, including details of physical appearance and the information about character those details revealed, on theoretical scales, with individual elements positioned for the purpose of comparison around an imaginary mid-point: a composite or average devised to anchor the system.”6 The concept of the average was applied not only to events such as weather or to abstractions such as prices, but also to social interactions and ultimately to persons. The average man exemplified norms of skill, circumstance, and behavior, revealing, in relief as it were, the aberrant extent of social qualities such as intelligence, impoverishment, or criminality. The average man also embodied an aesthetic standard, both in his own nondescript physical appearance and in his normative evaluation of the world around him. The average man who made his entrance onto the pavements of the city in the early nineteenth century became known as the man in the street, who was by the twentieth century understood to represent a norm of opinion and evaluation.7 His outward appearance or innate character was of less concern than his opinion, his feelings, and his thoughts.

The man in the street is a collective subject who stands for a commonality of experience rather than individuated, incommensurable experience; he is, moreover, an urban subject, for his street is the crowded sidewalk and busy thoroughfare of the city.8 The man in the street, through the representation of his presumptive feelings and thoughts, provides an expression of collective affect, a sensibility that arises from and responds to the surrounding urban environment, not passively but in an oscillation of acceptance and assertion.9 This collective affect, which because the man in the street is after all a fictional norm may not be the affective experience of any one actual person, may be provoked by any of the myriad registers of the city, its architecture certainly among them. The collective affect of the funeral procession along Lombard Street belongs in this category. Because the event was a mock funeral, its affect was not the cumulative feeling of individual mourners, but the shared impatience expressed by the slogan “The City Is Ugly Enough Already”; and this shared impatience was itself a response not to exceptionally ugly buildings, but to the awareness that ugliness was the architectural average of London. Even as the procession made its way down Lombard Street a different architectural conception of the average had begun to emerge, one that attempted an altered arrangement of the concerns of the man in the street.

A Metropolitan Architecture

The 1951 Festival of Britain, conceived as a centenary celebration of the Great Exhibition of 1851, evolved into a postwar celebration of the British nation and a stylized British way of life. Its pavilions, exhibits, and performances were instruments for the fashioning of a collective national audience, with the centerpiece of the Royal Festival Hall constructed as a permanent cultural center amid the temporary structures of the festival. Even as the festival grounds were being prepared, attention was given to the future development of its newly cleared and now very public grounds along the south bank of the Thames in the center of London. To what uses should this site be dedicated, and what future public audience might it address? These were the questions posed to the London County Council (LCC) by concerned journalists and professionals. Unsolicited proposals offered in the pages of the Architectural Review included monumental plans for boulevards and civic buildings as well as schemes that sought to insert a density of quotidian public activity with an assemblage of leisure and work programs. A 1949 sketch offered by Gordon Cullen, famous as one of the journal’s proponents of the neo-picturesque Townscape movement, shows a dense cascade of volumes and colorful surfaces tumbling down toward the river’s edge.10 The audience was, one presumes, a public taking its leisure with casual attention to visual interest.

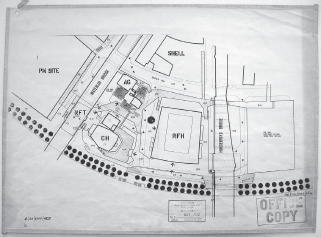

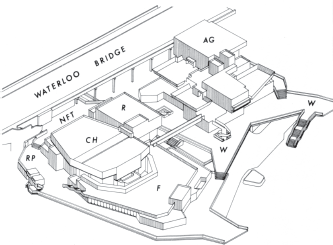

In 1953, the Town Planning Division of the LCC formalized an outline for the future development of the South Bank site all around the existing Royal Festival Hall, with a plan that included a conference center placed northeast of the hall in a tapered block. The taper was the formal indication of a radial arrangement, hinged at the rear of the site, that would retroactively fix the Festival Hall within a new geometric plan. Over the next several years, the overall scheme was revised, largely in response to programmatic changes that included the replacement of the conference center with a concert hall and an art gallery; and in 1961— two years after the Lombard Street funeral procession—the Architects’ Department of the LCC published its new, detailed proposal for the complex, which had now assumed a very different appearance.11 (Figure 16) While the Royal Festival Hall building had belatedly adopted the linear forms and referential conceits typical of prewar modernism, the new complex was a cluster of irregular forms that disregarded compositional geometries and ignored existing configurations implied by the site. Three volumes contained the programmatic spaces: two concert halls, the Queen Elizabeth Hall facing the river with the Purcell Room behind, and one art gallery, the Hayward Gallery, at the back of the site. Above street level, a deck loosely wrapped the concert halls and gallery; a pedestrian who descended onto the deck from Waterloo Bridge or climbed up to it from below could circumnavigate along a rambling route up and down stairs and along constantly widening or narrowing paths. (Figure 17) Much of the lower level was given over to car and service access and to a large undercroft opening toward the river. Originally intended to be faced with Portland stone (which despite John Wood’s efforts became the ubiquitous stone of London buildings), but eventually constructed with precast and cast-in-place concrete, the building would rise a few stories higher than the bridge, but would be smaller than and subordinate to the Festival Hall.

Figure 16. In the 1961 site plan for the new South Bank Arts Centre, the articulated forms of the concert hall (labeled CH) and the art gallery (AG) contrasted with the simplicity of the Royal Festival Hall (RFH). The site of the new Shell Centre, then under construction, is indicated at the top of the drawing. London County Council Architects’ Department.

Figure 17. An axonometric drawing of the South Bank Arts Centre shows the irregular forms and circuitous paths of the walkways surrounding the concert halls and the art gallery. The pedestrian stair to Waterloo Bridge can be seen at the far left. London County Council Architects’ Department.

Construction of this remarkable urban concoction proceeded ahead, but no sooner had the first phase of the South Bank Arts Centre opened in 1967 than a Daily Mail survey nominated it as “Britain’s Ugliest Building.”12 This epithet—ugly—has attached to the complex with remarkable consistency over the past four decades, supplemented by a supporting cast of adjectives like surly, bunker-like, barbaric, dank (according to the architect Richard [now Lord] Rogers), bleak (so said the imposing architectural historian Sir Nikolaus Pevsner). Even advocates have tended to offer quite temperate praise, with one, for example, expressing hope that over time the design would “assert itself and make people learn to like what at first was unfamiliar and hateful.”13 In a 1968 review of the building, the critic Charles Jencks acknowledged the preponderance of hostile reactions—“One man’s meat is another man’s poison,” he wrote—but countered them with a challenge: “All this criticism which has occurred, while understandable, is slightly beside the point. [The building] was probably intended to be conventionally ugly. So while the critics may have reacted in the right way, they have drawn the wrong conclusions. It is rather as if the critic reacted correctly to a gargoyle, a grotesque or a Francis Bacon only to reject them as unbeautiful.”14 Jencks provokes a different question beyond the superficial judgment of taste as to whether or not the building is ugly; the question instead is this: What might be the correct conclusions to be drawn from the ugliness of this architecture? And therefore what conclusions might be drawn from architectural ugliness more generally, as an aesthetic or experiential quality, and also as a social condition? The question brings forward into view the respondent to the architecture, the person who encounters the ugly architecture, and the transaction between that person and those persons of the architectural process—architects, builders, civil servants, critics—who brought the building into existence.

The final design of the South Bank Arts Centre was the work of the Department of Architecture and Civic Design of the Greater London Council (GLC), the geographically expanded successor to the LCC. The LCC and, from 1965, the GLC constituted a level of government between local representation as provided by the councils of individual boroughs and national governance as embodied by Parliament. It was a directly elected body; each London constituency elected one member of Parliament and two councilors to the LCC. Representation of the metropolitan citizen, whose interests but also whose manner of inhabiting the civic sphere were presumed to be distinct from those of citizens in the more bounded social environments of towns or villages, had a managerial cast indebted to the nineteenth-century concern for the average. The councilors of the LCC typically had professional or administrative backgrounds, and under their authority a series of professionally managed departments took charge of public services in the greater metropolis, services such as Education and Health. The LCC supervised a Town Planning Division and an Architects’ Department (subsequently the Department of Architecture and Civic Design) which during and after the war facilitated plans for the coordinated reconstruction of the city and sought to provide housing and new educational and health facilities, and to develop cultural centers in London.

These departments were large in both staff and portfolio, functioning essentially as corporate offices with a hierarchy of administrators, designers, and technical specialists. Sir Leslie Martin (architect of the Royal Festival Hall) was appointed chief architect of the department in 1953 and hired the two assistants, Norman Engleback and John Attenborough, who would continue to lead the South Bank project after Martin departed in 1956 to assume the chair of architecture at Cambridge University. Martin’s successor, Hubert Bennett, though unsupportive of the design that emerged under Engleback’s direction, was unable to press an alternative scheme. In the context of the postwar welfare state and its expansion of government roles, the Architects’ Department of the LCC was simultaneously an environment of civil service and of architectural experimentation, with three thousand employees but many of them grouped into studios working independently upon their projects. Within Engleback’s group were three young architects who could claim credit for the new design being in Jencks’s words “conventionally ugly”: Warren Chalk, Dennis Crompton, and Ron Herron, who by the time Queen Elizabeth inaugurated the building in 1968 would be very well known as members of Archigram.15

Within the networks of architectural discourse, Archigram was disseminating a radical critique of the conventions of modernism, advocating a more urgent embrace of technological change to accompany the social transformations of those years. While the polemics of Archigram did not circulate widely beyond architectural circles, they were paralleled by another architectural movement to which the South Bank Arts Centre was bound that had begun to attain considerable prominence. The New Brutalism, as it was known, was elucidated and for a time evangelized by the critic Reyner Banham, whose essays for architectural journals and criticism for wider circulating magazines gave attention to the emergence of a distinctive architectural attitude that proposed the value of a more direct, unmediated confrontation between a building and its occupant. The New Brutalism quickly became associated with the characteristic materiality of concrete, and with correspondingly heavy massing and more crudely articulated forms. Myriad strands of architectural experimentation extended outward from the New Brutalism, geographically as it was adapted in some form on every inhabited continent, and stylistically as it continued to serve as a signifier of urban, institutional architecture. For its early advocates, the New Brutalism was to be understood not, or not only, as an aesthetic, but as an ethic, and therefore an interjection of the person of the architect into the appearance of the architecture. For Banham, three traits in particular were to be emphasized, each with aesthetic and ethical implications: the use of materials “as found”—meaning unadulterated by finishes or treatments beyond their process of manufacture—the constitution of structure as a clearly understood relationship of parts, and the production of an affecting “image”; these three traits, he argued, were the constitutive properties of the architectural je-m’en-foutisme or “bloody-mindedness” of New Brutalism.16 It is hardly remarkable to suggest that the ugliness of the South Bank Arts Centre is precipitated by its brutalist approach— the adjective “ugly” is never far from any brutalist building—but the metropolitan intention of this building in particular points toward an understanding of ugliness as something other than a companion term for appearance.

Figure 18. The board-marked concrete surfaces, precast panels, and heavy, cantilevered forms are all visible in the view toward the Hayward Gallery as seen from the upper-level court of the Queen Elizabeth Hall. The concrete surface at the right of the photograph is the parapet of the bridge connecting the upper levels of the concert venues and the gallery. Greater London Council, Department of Architecture & Civic Design, South Bank Arts Centre (1968).

The Pile and the Puddle

Banham predicted that the Architects’ Department “will find its most obvious monument in the only major example of the quasi-fortified/neo-antheap/more crumbly-aesthetic manner in the country, the extension to the Royal Festival Hall, now raising its mini-Ziggurats over the parapet of Waterloo bridge.”17 (Figure 18) If the shape and appearance of the South Bank Arts Centre are to be considered as the constitutive aspects of its ugliness, subject to analysis or interpretation, then a more productive approach than the rubrics of style may be to take Banham’s hint and understand the architecture as a manner and an approach, and perhaps to regard the architecture less as the consolidation of conventional traits of ugliness than as an insufficiency of not-ugliness. An encounter with the rambling architecture of the South Bank Arts Centre readily incited the verdict of ugliness, Jencks proposed, because “there is no underlying coherence, no visual logic which helps to explain the functional logic. . . . [The programmatic spaces] hide behind a confusing, hostile pile of jagged in-situ sludge.”18 Warren Chalk, the architect responsible for the complex walkways, explained that “the original basic concept was to produce an anonymous pile, subservient to a series of pedestrian walkways, a sort of Mappin Terrace for people instead of goats.”19 An artificial mountain landscape built at the London Zoo in 1914, Mappin Terrace was an early experimental use of reinforced concrete; it was a purposeful and considered design of form, purposeful but not precise (as evidenced by the fact that it has since served as habitat for a variety of animals). There is an echo of the humorous and positive appropriation of ugliness by the Ugly Club of Liverpool in Chalk’s offhand likening of a shapeless mound of concrete to his newly designed civic architecture, but his aesthetic claim was serious. Like Mappin Terrace, the pile at South Bank was fashioned for use and for occupation without the aim of a precise compositional whole, or a precise form.

Individual parts of the complex did have highly specific criteria. For example, interior spaces had requirements for egress, and the concert halls had acoustical imperatives with ramifications for the selection of finishes and the regulation of air flow through the ductwork. But outside on the decks, people were to be free to circulate, to enter or bypass the venues, their movements accommodated with contours rather than geometric determination. The resulting asymmetries, the shifts and skips in levels, and the ubiquitous spatial expansions and contractions tolerate so much variation that any prospective continuities of configuration dissolve. The massing of the complex, decomposed into two heaps, similarly refuses to reveal causations, hierarchies, or relevancies. (Figure 19) Viewed looking across a street toward the Hayward Gallery, the parts fend for themselves or compete with one another, separately invoke concerns for technology, human occupants, or environment; not only the three programmatic centers, but also their smaller components, the staircases, curved and straight, serrated skylights, extruded balconies, and individual walls. No a priori logic generated the differentiated forms, nor does a totalizing or harmonizing framework of alignments harness them a posteriori. The overtly visible but indeterminate form results from the accumulation of incremental decisions, each of which alters the configuration to which it has been added without tending toward any precisely fixed end. The architecture is in fact a pile, just as Chalk—taking advantage of the double sense of the word as both a heap and a building of some distinct size and pedigree—claimed it was intended to be.

Figure 19. A pile of concrete forms, the mass of the South Bank Arts Centre as seen from Belvedere Road looking toward the Hayward Gallery, with the Queen Elizabeth Hall beyond. Greater London Council, Department of Architecture & Civic Design, South Bank Arts Centre (1968).

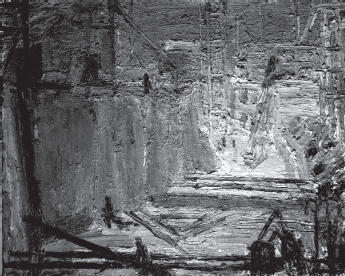

Suspended in a process of formation, of constant increase or decrease, a pile is always a lack or insufficiency of form. In the pile alongside the Thames, no fixed relation to site, no hierarchy of movement, no interdependency of structure, and no imposed geometric order has determined a fixed arrangement of parts. This indeterminacy, like the mountainous shape of Mappin Terrace, enables possibilities without prescribing (or proscribing) further contingencies. It is difficult to recognize that the pile is not a transient stage prior to some future completion, but the actualization of indeterminacy. Consider, however, that throughout the 1950s and well into the 1960s the physical state of London was inescapably defined by the projects of reconstruction. A pertinent illustration comes from a series of paintings of London building sites by Frank Auerbach. (Figure 20) One of the paintings, The Shell Building Site—painted like others with a technique of a thick, coarsely worked surface in a muddied palette—shows the construction of the Shell Centre, an office complex built immediately behind the South Bank site; revealed in it is the superimposition, over a raw, formless state of excavation works, of an emerging architectural order seen in pilings, girders, or cabling. To Auerbach, these appeared as simultaneous events, the one coexistent with the other, identifying incompleteness in a positive sense as a moment in which potentials had not been forestalled, in which change and differentiation were preserved.

Figure 20. Frank Auerbach, The Shell Building Site (1959). Oil on board, 122 x 154 cm.

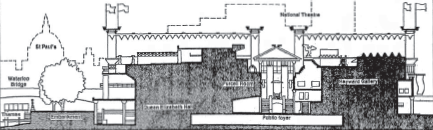

Since its opening in the late 1960s, other architects, commissioned or not, have not hesitated in imagining changes to the South Bank Arts Centre. In 1979, Architectural Review published a proposal to fill in the “dark, wasted areas” of voids and overhangs at the complex with glazed enclosures, in effect smoothing out the irregular contours of the original buildings, so that the complex might be “transformed from its rock-like isolation.”20 In a 1984 consultancy, architect Cedric Price suggested a less complicated but perhaps equally forceful strategy to unify the complex by painting it and the Festival Hall a uniform color, “London Cream.” The next year, architect Sir Terry Farrell proposed encasing the existing complex inside a new, larger building with a closer resemblance to the Festival Hall; later versions of the scheme proposed demolishing the halls and gallery rather than containing them. (Figure 21) By 1992, a petition for listing had been rejected by Secretary of State Michael Heseltine, and a 1994 competition solicited larger-scale interventions that would redress the deficiencies of the brutalist buildings without disturbing the presumptively complete form of the adjacent Royal Festival Hall. Two of the finalists, the architectural firms Michael Hopkins and Partners and Richard Rogers Partnership, proposed the same strategy: a roof over the South Bank Arts Centre. For Hopkins, the roof would be one of the firm’s characteristic tents, eight pylons stretching a bowed fabric roof across the Queen Elizabeth Hall and the Hayward Gallery.21 The new profile would give the Royal Festival Hall a fraternal twin, with the original shape of the arts complex disguised beneath a more uniform shell, and with the concrete of the original building shadowed under the lighter, more supple material above. Rogers also sought to reconcile the arts complex with the Festival Hall by revealing the one and concealing the other. He proposed to spread an enormous glazed roof across the site, a glass wave rising up from the base of the Festival Hall and sweeping over the Hayward Gallery and the Queen Elizabeth Hall, submerging them inside what was immediately dubbed a new Crystal Palace. (Figure 22) The corrective intention of the design was evidenced by the smooth, sweeping roof’s enshrouding of the disorderly pieces of the original complex.

Figure 21. Sir Terry Farrell’s 1985 proposal for the renovation of the South Bank Arts Centre. The sectional view shows the two concert halls and the art gallery contained inside a new superstructure and linked by a new formal entrance and foyer.

While these corrections, ameliorations, and compensations for the original design’s perceived lack of form went unrealized, the most recent attempt has proceeded closer to fruition. In 2013, what is now the Southbank Centre announced a major refurbishment of the concert halls and gallery and the addition of new spaces for rehearsal facilities and public functions. (Figure 23) The architecture firm Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios released models and renderings that showed two new glass volumes raised above the original concrete mass, one a rectangular bar running behind the concert hall parallel to Waterloo Bridge, and the other an elevated box perched above the gap between the halls and the gallery. Below the deck walkways, the undercroft was also to be enclosed and claimed as interior for the complex. Modified in response to its reception from professional and public audiences, the design is currently proceeding with a different scope, with the refurbishment of the halls the first priority.22 The scheme itself adopts something of the logic of the original structure, choosing to add to the pile a few more volumetric additions, rather than to conceal and smooth the pile itself. These additions, however, are themselves sharply defined and prismatic, less indulgent toward uncertainties of form; and they are clad in glass, whose varied colors in reflection would present a sharp contrast to the uniform grayness of the concrete upon which they sit.

Figure 22. The Richard Rogers Partnership 1994 proposal to place a curving glass and steel roof over the South Bank Arts Centre. The Hayward Gallery would protrude through the roof toward the rear of the site, and a seam in the curve of the roof would make the Queen Elizabeth Hall visible from the river.

Figure 23. The initial proposal by Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios for the redevelopment of the South Bank Arts Centre, in which two new volumes would be added to the existing concrete pile. The plans for redevelopment have since changed significantly and the design concept amended.

The materials employed in all of these proposed remedies—Rogers’s smooth glass wave or Hopkins’s taut plastic skin or FCB Studios’ glass prisms—counter the brutalist architecture just as much as each design’s respective consolidations of form. All of the proposals have sought to transform the exterior space into interior to make the terraces and connections between the buildings habitable, useful for cafes or shops, but these are not only programmatic changes; they would alter the balance of exterior and interior, changing the complex from an architecture whose external surfaces are the primary factor of encounter to an architecture of enclosure, protecting inhabitants from the rain, and of varied surfaces, themselves protected from the contingencies of weather. It was one of Banham’s exemplary traits of brutalism that materials be employed “as found,” unalloyed and unadulterated materials displayed in architectural form. In the South Bank Arts Centre, precast concrete panels and poured concrete surfaces surround any visitor. Roofs, walls, and columns cast as one piece assert the structural primacy of the material, while board markings or the grain of aggregate on individual surfaces give direct emphasis to its sensible qualities. (see Figure 18) Many critics of the architecture have singled out for particular comment the pervasive concrete: its drab grayness in the weak light, its coarse texture, its inhospitable coolness, and, inevitably, its appearance when it rains.

The atmosphere that shaped the experience and understanding of nineteenth-century London had a continued effect upon the city of the twentieth century. A sympathetic reviewer in 1967 offered a prophetic warning: “For the visual excitement of turning a roof into a wall without changing material or finish, and without tiresome drips or the petty intervention of a gutter, one has to accept a bedraggled look on a rainy day, possibly resulting in permanent staining.”23 Such stains upon its concrete surface—which the architecture does incur and even encourage with its lack of any transitional detail along its edges—produce an additional dimension of ugliness separate from that produced by the pile’s lack of form. These stains are as pervasive as the concrete they mark, occurring in the damp streaks along vertical edges and in the residual puddles scattered across horizontal planes. Weathering has not been the only cause of the stained surfaces; the undercroft, long since appropriated by skateboarders and other urban constituencies, has been covered in graffiti layered over the concrete surface. (Figure 24) The marks of rainwater and graffiti need not be distinguished from one another on account of provenance. Both are stains, and not in any presumptively negative sense, but insofar as both are what the architectural theorist Mark Cousins, in his focused reflection upon the concept of the ugly, calls the characteristic of an excess: “A stain must be cleansed. Is this because the stain is ugly? The stain is not an aesthetic issue as such. It is a question of something that should not be there and so must be removed. The constitutive experience is therefore of an object which should not be there; in this way it is a condition of ugliness.”24

Even if less intentional than the lack of form, this second dimension, this excess out of place, is very much a part of what Jencks called the intentional ugliness of the architecture. Cousins’s assertion that the stain “is not an aesthetic issue as such” does not imply a separation or segregation of ugliness and the aesthetic register, but instead underscores the relational character of ugliness, that ugliness is neither absolute nor essence, but is a relational circumstance. So to what end is the intentional ugliness of the South Bank Arts Centre directed, and what kind of response does it warrant? For some experience was clearly anticipated by the accommodation or solicitation of stains. The New Brutalism “requires that the building should be an immediately apprehensible visual entity, and that the form grasped by the eye should be confirmed by the experience of the building in use”; but Banham further elaborated that while classical aesthetics would presume the value of this apprehension to be pleasure in regard to something beautiful, for New Brutalism its value might accrue in “quod visum perturbat—that which seen, affects the emotions,” with pleasure, displeasure, or, pointedly, an admixture of the two.25

Figure 24. The graffiti-painted walls and columns of the skatepark in the undercroft below the walkways surrounding the Queen Elizabeth Hall. The overhang at the top of the building carries water stains across its concrete surface.

The Man on the Omnibus

The values of visual apprehension and visual entities were at this same time being adduced (in very different fashion than Banham) by the historian Nikolaus Pevsner, who was then a leading advocate for the “Visual Planning” of urban settings, or what was also known as Townscape. Drawing forthrightly upon the legacy of the picturesque movement, Townscape gave attention to the dynamic experience of the city and above all to vision, which would, in Pevsner’s conception, serve to coordinate the individual person with the highly varied urban environment.26 In place of the modernist plan, Pevsner was advocating that the modernist promenade or movement be construed as the decisive instrument of configuration. A visitor to the South Bank Arts Centre might be surprised by its indeterminate form in much the same way as a visitor to Prior Park would be surprised by the changeable nature of Alexander Pope’s wilderness. Except that the subjectivity invoked by Pevsner and other practitioners of the neo-picturesque was not that of the subject addressed by the ugliness of the South Bank Arts Centre; nor was his ideal of a calibrated concatenation of diverse forms the aim of the consolidated singularities of its ugly architecture. Writing the entry on the South Bank Arts Centre for his authoritative Buildings of England series, Pevsner conceded that its walkways produced “a thrilling experience, if the weather is fine and you are at leisure. But,” he challenged, “what if it rains, what if you are late, what if you find steps a strain?” Then the nearest comparison to the walkways’ “bleak effect [would be] Piranesi’s Carceri.”27 Pevsner’s critique reveals that the first two conditions of ugliness at the South Bank Arts Centre—its irresolution of form and the appearance of the stain—join with a third aspect of ugliness: the discomfiting sense of an architecture without empathy. The encounter between person and architecture is all roughness: the coarse concrete surfaces that are both tactile and injurious; the rambling terraces that solicit chance encounters but foil planned itineraries; the distortions of scale and orientation that defy commensuration; and the unsettling disarticulation of the architecture into parts and fragments. Where Townscape might have sought to employ these devices to produce a pleasurable confusion to be absorbed visually, the ugliness of the South Bank Arts Centre consists of an intrusive, situated dissonance.

This dissonance results not merely from infelicities of function, from the building not adequately serving its programmatic demands, or from insufficiencies of symbolic or associational legibility. It manifests from a third register of ugliness, not within the shape or material of architecture, but that consists of the relation between the architecture and the person who encounters it. When Mark Cousins suggested that the ugly object is an object out of place, he argued that it is not the disturbance of the original object that constitutes ugliness, but rather that the ugly object, by looming too large, by already exceeding its own bounds, threatens the sovereign subject. The ugly is that which is neither contained within itself nor capable of being contained by something outside itself, and as a disproportionality between architecture and a person, ugliness prevents the proper definition of boundaries, or of what should be separate and intact exteriorities.28 Ugliness compels disgust, as rendered in all of its actions and metaphors of repulsion, a self-preserving repulsion, whether in the form of vomiting, turning away, or crushing something underfoot, that sharply and immediately distances a person from the ugly object. Yet, however hostile some criticism of the South Bank Arts Centre has been, its ugly architecture does not prompt violent disgust manifested in physical nausea. The bleakness that Pevsner sensed, the oft-disparaged streaked concrete surfaces, the difficulty felt in navigating through the decks—these accumulate in the perception that the building is not sufficiently accommodating to its human users. All these elements prompt degrees of what is obviously displeasure, and though disgust would be found at the extreme of a spectrum of displeasure, ugliness has a more subtle key, one that prompts an affect more akin to irritation.

Where the urgency of disgust compels an unmistakably urgent withdrawal, the nagging affect of irritation emerges from a relentless proximity. The ugliness of this architecture irritates because of proximity, because it produces the sense of a mistaken, though not threatening, conflation of architecture and person. Unlike emotions, affects do not narrate the experience of a singular, coherent subject, but displace that experience into a separate, encompassing, collective mood. Affects are the relation between consciousness and circumstance, but detached from individual persons. Consequently, affects are more diffuse than emotions; they are vague, not unlike a pile or a stain. An ugly feeling (the expression is from the literary critic Sianne Ngai) such as envy or anxiety is induced by the lingering proximity of its source, condensing the interlaced factors of a given situation rather than apportioning them like the sharp emotions of disgust or anger. An ugly feeling emerges without precise causation from the perpetuation of the layered stimuli of a given situation, and the ugly feeling provoked by the South Bank Arts Centre thus summarizes the several and different instigations of a felt antipathy into a generalized but vivid mood: irritation. And while the active manner of disgust would provoke a violent overcoming of its objective cause through flight or fight, the passive manner of an ugly feeling like irritation could be extinguished only by a complete transformation of the situation from which that feeling emerges. Examples of such transformations might include almost any of the alterations proposed over the past three decades as fixes to the complex, but in the absence of transformation, irritation persists as a simultaneous pulling-together and pushing-apart of the person and the architecture.

The person who experienced this irritation in this way was not the solitary individual, not Nikolaus Pevsner as he skirted puddles to navigate his way through labyrinthine passages, nor simply individual “laymen” who, as one critic suggested, “do not take kindly to this kind of ‘architect’s architecture.’ ”29 For the architecture addressed a metropolitan body politic, the body politic that the London County Council itself represented—not only represented but in fact constituted, since that body politic had no prior historical, social, or geographic source of consolidation. The individual incarnation of this metropolitan body politic would have been the famous “man in the street,” who had appeared in the anti-ugly demonstrations of the late 1950s, or the “man at the back of the omnibus,” the surrogate for a standard of reasonableness in English common law. The average man and the reasonable man are historically intertwined; indeed, they were contemporaries in a sense—with the average man presented to the world by Adolph Quetelet in 1835 and the reasonable man making his first public appearance in 1837 in the case of Vaughan v. Menlove.30 Both figures enact a translation between collective matters of concern and individual, and otherwise irreducible, experience. They summarize a larger constellation of persons inhabiting the metropolitan realm into embodiments that express a norm against which the experience or intention of those persons can be understood, and they condense the individual discernments, opinions, and tastes of those persons into personifications of the qualities of consensus and reasonableness. (Figure 25)

Crucially, the man on the omnibus is a standard of reasonableness whose social function is not to provide summary judgment but to define a measurement of expectation—not a decision about a given situation but a calculation as to how that situation ought to be perceived. The man on the omnibus, in English common law, figures a sequence of probable choices and outcomes, or to put it more generally, a course of anticipation through a given situation; the man on the omnibus “would have anticipated that. . . .” The temporal orientation that he brings, therefore, is not in-the-present-ness but in-the-future or more precisely a future anteriority, a drawing of the future expectation into the decisive context of the present. It is the man on the omnibus who experiences irritation at South Bank, and that irritation (which, again, is an affect detached from individual persons) is therefore the collective affect experienced by the metropolitan body politic. The man on the omnibus experiences that irritation through the deferrals of this ugly architecture, because of its deliberate disconcerting of the certainties of the future anterior. This disconcertion occurs through a particular valence that has already been characterized as an aspect of the architectural ugliness of the South Bank Arts Centre: the valence of ordinariness. Even before the 1837 case of Vaughan v. Menlove gave clear description to the idea of reasonable anticipation, common law had employed notional figures that answered the need for collective embodiment; one such figure was coined in the early eighteenth century as the “person of ordinary capacity.” The 1837 case imagined “a man of ordinary prudence,” drawing the understanding of reasonableness together with an idea of ordinariness. With its display of unadulterated materiality, and its willingness to eschew the organizational priority of program or geometric form, the architecture of the South Bank Arts Centre placed its emphasis instead upon a notion of ordinariness. It was a commonplace that the New Brutalism was a relentless acceptance of ordinariness. But the consequence of the collective affect it produces is that one ordinariness (that of the architecture) disconcerts another ordinariness (that of the man on the omnibus).

Figure 25. The reasonable man, with a perfectly furled umbrella in hand, and other metropolitan citizens on the walkway in front of the Hayward Gallery. Greater London Council, Department of Architecture & Civic Design, South Bank Arts Centre (1968).

Deliberate Acts of Burlesque

Neither reasonableness nor irritation is historically fixed, and the ugliness of the South Bank Arts Centre is not merely a perpetuation of a metropolitan condition cast in place five decades ago. In his 1968 review, Charles Jencks predicted that the South Bank Arts Centre, unlike other contemporaneous architectural projects, would create an architectural setting “where one can imagine deliberate acts of burlesque,” an analytical perception that has proved prescient.31 Often these have been seemingly contained within the programmatic extents of the complex, in gallery exhibitions and concerts whose avant-garde intentions were accommodated by the architecture, but which also took advantage of its solicitation of further disconcertion of the metropolitan body politic.32 One of the first concerts performed in the newly inaugurated Queen Elizabeth Hall was Pink Floyd’s Games for May. On May 12, 1967, the band presented its gathered audience with the first experience of surround sound projected from a quadraphonic speaker system. (Figure 26) With sound effects—footsteps, bird sounds, and Roger Waters’s unsettling laughter—distributed back and forth across the hall by the control of a single joystick, and with additional effects such as an artificial sunrise, giant soap bubbles, and a gong sounded by thrown potatoes, the concert’s high-volume musical burlesque would have surprised even an ardent fan. The Financial Times praised the show as the “noisiest and prettiest display ever seen on the South Bank,” and a reviewer for the International Times (a leading underground newspaper) agreed, noting the effect in spatial terms: “The choice of the Queen Elizabeth Hall for the Games of May event was really good thinking, for it was a genuine twentieth-century chamber music concert. [The performance] moved right into the hall and into the realm of involvement.” From the radically novel perspective represented by Pink Floyd and their musical experimentation, the architecture itself was, in the critic’s view, rather ordinary: “On the whole, it was good to see the strength of a hip show holding its own in such a museum like and square environment.”33

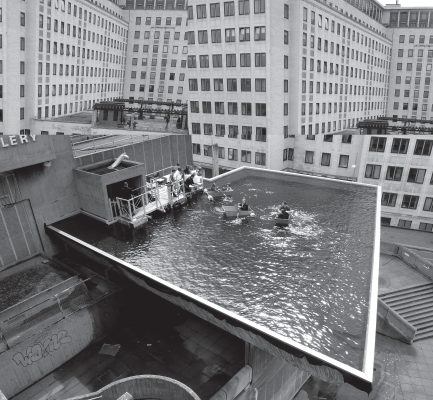

In its capacity to synthesize different dimensions of vagueness—the irregular form, the stained surface, the irritating affect—ugliness produces a consequence that is available to such appropriations, to deliberate acts of burlesque. Even though the review of Games for May chose to see the music and architecture—or perhaps more accurately to see Pink Floyd and the GLC—in sharp contrast to one another, it is more the case that the performance had adjudged and seized upon a potentiality in the ugliness of the architecture. In 2008, the Hayward Gallery celebrated its fortieth anniversary with Psycho Buildings, an exhibition about the peculiar relationship between people and architecture.34 The Hayward building has, on its uppermost level, three sculpture terraces whose steeply angled parapets add to the overall restlessness of the forms of the South Bank Arts Centre. Though actually extensions of the gallery’s interior space, they imply that the lower pedestrian deck that forms an irregular surround at the entry level continues into, through, and out of the buildings at the upper level. During the Psycho Buildings exhibition, the trapezoidal terrace on the southeastern corner was the site of an improbable installation by the artists’ collective Gelitin: a boating pond. Normally, Proceeding and Unrestricted with without Title (a convolution of a nautical definition used in accident logs) consisted of three plywood boats, a floating jetty, and a pond created by filling the entire pan of the terrace up to the top edge of the surrounding parapet. (Figure 27) The jetty, a willfully ugly contraption, was jerry-built from scrap and listed unexpectedly. The boats were similarly ugly, inverted pyramidal shapes in which two people sat facing each other, one pulling at a pair of shortened oars, with two empty five-gallon water jugs as stabilizers. Clumsy but seaworthy, they could be propelled around the pond with reasonable facility. The depth of the pond wasn’t much more than a meter, but the black lining of the terrace and the reflections on the surface made it impossible to judge, and with the water up to the parapet edge an exaggeration of dimension gave a sensation of more serious nautical endeavor, one conducted fifteen meters above the ground.

Figure 26. Pink Floyd rehearses for Games for May, performed in the Queen Elizabeth Hall on May 12, 1967.

Figure 27. Gelitin, Normally, Proceeding and Unrestricted with without Title, Hayward Gallery, London (2008). Photo collage by Gelitin, with background composed of partial views of the Shell Centre.

Resonances with the original expedience of the Hayward design were readily found: the rickety jetty hammered together from bits made use of the “as-found” approach, for example, and the resulting wooden pile was as formally incoherent but as functionally capable as the surrounding concrete pile. The boats, too, were case studies in expedience. Simple plywood forms without graceful lines but with workable oarlocks and requisite stability to go where directed. And to create the pond itself, the formula couldn’t be simpler. Take one existing terrace, plug the existing drainage holes, fill with water. But it is this easy only once one has taken note of the actual parapets of the Hayward terraces, typically brutalist in their monolithic cast but distinctive in the raked slant that gives them the shape of trays or basins. Gelitin thereby produced what the exhibition pamphlet described as the “incongruity of [a] pastoral idyll suspended high above the ground and nestling against The Hayward’s concrete Brutalism.”35 Superimposed upon the architecture, the boating pond became another puddle, larger and more purposeful but not separate from the other atmospheric manifestations of the architecture. The surface of the water both echoed and contradicted the board-formed concrete of the parapet. The smoothness it created differed from the smoothness of the roof enclosures that had once been proposed as correctives; not a wave now, but a puddle embedded within the ugliness of the architecture. At the outer edge of the terrace, the seeping stain of water would now result from the overflow of the pond, rather than rainfall, so that the stain, that which still does not belong, is nevertheless fully part of a legible performance of ugliness.

In his 1984 Report on South Bank, an analysis of the deficiencies and the potentials of the complex, Cedric Price concluded that “this unique area—half water, half land—must be available for massive human individual & collective endeavour, skill, delight and imagination. It must be more than a city lung—it must encourage its users to help generate its vast potential for human use. . . . If it can do even more than distort time and place for human dignity, understanding & delight (which is what the British Museum does) then it must do so by providing an opportunity for activities and aspirations—for both individuals and the crowd—hitherto thought impossible.”36 Both Games for May and Normally, Proceeding, by performing such impossibilities, revealed that positive category of experience that ugliness enables, a state of misalignment or disconcert between two respective domains—architecture and the body politic. A condition of friction that does not rise to the state of conflict, the passive affect of irritation never rises into disgust and a consequent resolution (through some necessary escape from or removal of the object of disgust). Instead, irritation produces a curious state of equilibrium, insofar as neither the embodiment that registers the friction nor the context in which that friction occurs may have a greater claim to propriety—to being in the right place—than the other. Perhaps the terrace always was a boating pond after all? Or perhaps the undercroft was a village green? This was the clever hypothesis of campaigners seeking to protect the undercroft as a skatepark once the most recent plan for improvements was announced; they petitioned to have the space recognized as a community space under the Commons Act 2006, designed to protect communal civic spaces such as village greens.37 Two ordinary (and, it should be noted, nonurban) spaces, a boating pond and a village green, occupy the same space and time as the other ordinariness of the deliberately ugly architecture of the South Bank Arts Centre.

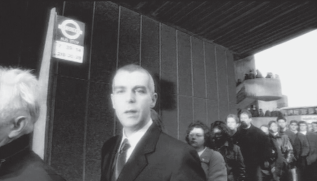

Figure 28. Pet Shop Boys, “Red Letter Day.” Howard Greenhalgh, director (1997).

In yet another burlesque, the man on the omnibus, that metropolitan subject of routine and expectation, encounters the architecture of the South Bank Arts Centre in the scenes of the music video for “Red Letter Day” by the Pet Shop Boys.38 (Figure 28) The staged encounters, organized as the queues that shape much of daily urban life, give visual expression to a fragmentary narrative. With each irritable judgment of the ugliness of the architecture, the collective metropolitan subject expresses a misalignment of expectation and circumstance, but through the scenes of the extended queue winding through the architecture, as through the shortlived boating pond on its balcony and the decades-old village green in its undercroft, a novel calibration of average and exception comes into view. The average man is not met with an average architecture, but neither is the exceptional architecture met with an exceptional person. John Wood had aimed, two centuries earlier, to align an improved behavior of the Company with improved sidewalks and facades, the orderliness of the one to reinforce the other. On the south bank of the Thames, the metropolitan subject and the metropolitan architecture are brought together toward a different civic end, not a resolved order achieved by beauty, but a novel indeterminacy enabled by ugliness. By soliciting and giving substance to the affective experience of irritation, the deliberately ugly architecture transforms the individual judgment of complaint and dislike into the collective judgment of dissatisfaction and changing expectation.