Chapter 5

The Architect

On September 30, 1812, the Morning Post published a letter from a reader identified as “Ambulator,” who wrote to complain of a “nuisance” he had encountered: “I presume you have not lately passed through Lincoln’sinn-fields, otherwise I think you would have animadverted on a new-fangled projection now erecting on the Holborn side of that fine square. This ridiculous piece of architecture destroys the uniformity of the row, and is a palpable eye-sore.”1 The ridiculous eyesore was the facade of 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, the home of the architect Sir John Soane. Soane, who was in the midst of transforming the interiors of his adjacent townhouses, had begun to construct a projecting stone structure—portico, loggia, and balcony—that covered the three bays of the facade and rose to a height of three stories, creating a startling contrast with the flat and unadorned brick facades of the flanking terrace. The idiosyncratic gesture was noticed in the press, and by local authorities; a second letter to the Morning Post published a few days after Ambulator’s advised the editor that “a multitude of other persons” had complained of the extraordinary ornamented facade that disrupted the uniformity of house fronts, and that the district surveyor, judging it to contravene the Building Act, had “lodged an information against the unsightly projection” with the local magistrates.2 (Figure 40)

The district surveyor, William Kinnard, had indeed advised Soane that the projection violated Statute 14 George III, cap. 78, commonly known as the Building Act, which prohibited enclosed projections to extend beyond “the general line of the fronts of the houses” on a street.3 In their accounts of the case, heard before the magistrates at the Public Office in Bow Street, the Morning Post and the Sun reported that Kinnard represented the facade as a public nuisance, to which Soane’s counsel replied that the work could in no way be considered a public nuisance, as it did not extend past the line of Soane’s freehold, the line of his property, which lay several feet beyond the projection. “A common nuisance must be that which deprives the public of some advantage, or puts them to some inconvenience,” he argued, but this could not be the case at 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, where the public was not permitted to enter Soane’s freehold and thus was never in proximity to the facade.4 (Figure 41) To further his defense, Soane’s counsel introduced models of other buildings on Lincoln’s Inn Fields that had included similar projections without legal censure. Kinnard’s attempt to distinguish the permissibility of these examples failed, and the magistrates ruled in Soane’s favor. Kinnard appealed the magistrates’ decision to the King’s Bench, where the presiding judge Lord Ellenborough refused to grant an appeal because the district surveyor was not himself “aggrieved” by the magistrate’s decision—that is, he did not suffer any private harm from it—and was therefore not entitled to be heard.5

Figure 40. Correspondence to the editor of the Morning Post and other newspapers, with commentary discoursing on the propriety of the facade of Sir John Soane’s house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

Figure 41. The controversial facade of 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, with its projecting portico and loggia. The railing in the foreground shows the boundary of Soane’s freehold, which he had purchased in 1807.

This case was evidently of considerable interest, probably as much for its relevance to property owners throughout London as for Soane’s celebrity; the Sun noted that the “cause excited great anxiety and curiosity in the minds of many professional men of eminence who attended, and who seemed unanimously to applaud the decision.”6 Even though it received legal approbation from the court, and perhaps the endorsement of spectators at the trial, the facade of 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields could still be, and was, regarded by the public that passed by or that read descriptions of it in newspapers as a curiosity of private taste. The attention now drawn by this seeming transgression solicited a justification independent from that required by law, but one that maintained a comparable emphasis on the distinction of public and private realms. The public aspect of Soane’s house, its conspicuously assertive facade, could be sanctioned by law only because of its status as private property; it was not public, did not physically intrude upon the public, and could not therefore be a public nuisance. It did, however, intrude upon the aesthetic attention of the public by its visibility and its idiosyncrasy. The justification of this intrusion lay in the singular imagination of the architect, whose private precinct of artistic creation was, like the physical building, removed from yet fully present within the public sphere. The publicness of Soane’s house and the public notice it engendered projected this embodiment of architectural thought into the public sphere while simultaneously withholding it as a private entity.

The irrevocable projection of the architect’s palpable eyesore into the public realm would occur two decades later when the House of Commons approved the private act of Parliament bequeathing Sir John Soane’s house to the public as a museum. It was Joseph Hume, MP (a few years prior to his crucial intervention in the rebuilding of the Houses of Parliament) who presented the case for accepting this “noble and disinterested” gift to the nation.7 Prior to the final reading and vote, the members of the House of Commons debated for the better part of an hour the legality and morality of Soane’s donation, raising implicit and explicit questions about Soane’s private character and his public reputation. Despite Hume’s endorsement, some members of Parliament found fault with the donation, questioning the propriety of alienating his descendants from the property they might have inherited; other members then stood to rebut various aspersions upon Soane’s motives. The house and its idiosyncratic architecture, the debate suggested, were a proxy for Soane’s private character. Ultimately, with Soane’s reputation successfully defended, the Soane’s Museum Bill entered into law as private Act, 3 William IV, cap. iv. With the strict stipulation that the house and its contents be preserved in their arrangement and condition upon Soane’s death, the palpable eyesore of Lincoln’s Inn Fields became the real property of the public.

Libel

The London in which Soane resided offered countless venues for production and exchange of opinions; there were streams of correspondence to circulate news and gossip, which then made their way into personal diaries, pamphlets, or journals; there were debates and lectures, staged in drawing rooms and coffee houses, academies and Parliament. During the years of Soane’s architectural career, talk in all these forms was the medium of “publicity,” a word coined at the end of the eighteenth century to describe the condition of entering into the public sphere and being rendered an object of public attention.8 At that time, dozens of different daily, weekly, and monthly newspapers and journals constituted the London press, the most popular of which had circulations in the thousands. Although limited to an educated and reasonably affluent readership, they wielded a powerful influence with an amalgam of political commentary, literary reviews, artistic criticism, legal reports, financial data, and society affairs that, taken together, produced a constantly changing rendering of publicity and reputation. Soane himself not only read these publications—he subscribed to the Examiner, Gentleman’s Magazine, and European Magazine, among others—but appeared in them as well. His name can be found in the pages of the Morning Post, Morning Chronicle, Examiner, Literary Gazette, Times, Sun, True Briton, Champion, Guardian, and Observer. His attentive and persistent interest in these media is apparent in twenty-one scrapbooks in which he compiled newspaper clippings about himself and other favored topics.9

Not all of the attention offered by these publications was favorable. On October 16, 1796, the Observer published a short poem with a comment that its anonymous verses delivered a satire “so just as to obtain for them a place in the Observer.”10 Titled “The Modern Goth,” this poem had circulated as a printed pamphlet several months earlier after first being read aloud at a meeting of the Architects’ Club, a sociable professional club of which Soane was a founding member and in which frequent and vociferous disputes had perhaps set a precedent for what amounted to a quite public derision. The poem’s rhyming couplets sarcastically praised Soane and his new designs for the Bank of England. Belittling comments on his diverse architectural practice—“Glory to thee Great Artist Soul of Taste / For mending pigsties when a plank’s misplaced”—were set alongside hyperbolic epithets deriding the peculiarities of his architectural style and its interpretive development of classical precedent by noting its “pilasters scor’d like loins of pork” and seeing its “order in confusion move / scrolls fixed below and pedestals above.” The poem ended with the succinct advice: “In silence build from models of Your own / And never imitate the Works of Sxxne.”11 The poem, once published and circulated in this manner, presented a public criticism, quite scathing in its tone, of the outward appearance and aesthetic consequence of Soane’s architecture, and sneering at what it regarded as his pretensions to taste. (Figure 42) Satirical poems aimed at prominent figures were common currency in political and literary exchanges, and “The Modern Goth” employed their typical devices: ironic classical allusion, mocking praise, and the judicious use of innuendo by the elision of letters from Soane’s name in the final line of the poem. These elements were of crucial importance, for satire often met with the equally common response of a suit for libel, and the strategy of innuendo could allow an author to evade the charge.12

During the course of the eighteenth century, instances of libel had been given greater prominence by the increase in published materials and by the intensity of partisan debate, and legal standards for libel soon accommodated the entire range of public discourse from political dissent to critical reviews. Libel could be charged as a crime or as a tort, and while criminal prosecutions drew much attention, the law courts heard civil suits with considerable and increasing frequency. Common law permitted an evolving conception of libel, without fixed or statutory definition, based upon two constituent criteria: defamation and publicity. Defamation was an injury to an individual’s reputation, which was considered a legal right: “The common law [protects] the good fame, as well as the life, liberty, and property of every man—It considers reputation, not only as one of our pure and absolute rights, but as an outwork which defends, and renders them all valuable.”13 Because only a defamation conveyed to a third party could provide cause for libel, a claim also required evidence that the injurious statement had been published, that it had, even in the most circumscribed sense, been made public. Even with these criteria, though, the changing circumstances of media and the mutable nature of common law would have meant that a critical statement such as that directed at Soane could not definitely be known as libel prior to the presentation of legal arguments.

Figure 42. Soane’s design for the Bank Stock Office in the Bank of England, with its incised ornamentation, profusion of vaults of several different types, and original interpretation of classical models, was one example of the architectural novelty derided by the author of “The Modern Goth.” Joseph Michael Gandy, presentation drawing of the Bank Stock Office (June 7, 1798).

Soane’s designs for the Bank of England, an institution of enormous civic and political importance, could hardly have avoided exciting public comment, particularly in light of their disregard for prevailing architectural conventions. Though a private institution, the bank, due to its issuance of the national debt, occupied a central role in the governance and political economy of Great Britain. Soane’s design for its enormous building in the City of London bore the responsibility of national representation, a responsibility that likely accentuated the severity of the poetical critique.14 Soane chose not to ignore the satirical attack. Nor did he rebut it with a satirical response of his own, a common enough strategy but difficult in this instance because the actual author remained anonymous. Nearly three years passed before he could act, but in 1799 Soane began legal proceedings against surveyor Philip Norris, whom he named as the “Publisher” of “The Modern Goth” and a second, equally disparaging poem. (Figure 43) With the encouragement of his legal counsel, Soane submitted to the Court of the King’s Bench a brief that, emphasizing the “scandalous, malicious, inflammatory” nature of the works, asserted that the defendant intended “to prejudice, vilify and disgrace the said J.S. in his profession and to injure his fame, credit and reputation.”15

Under prevailing law, civil prosecution for libel could proceed against published statements about an individual that either impaired his position in society by holding him up to public “scorn and ridicule” or that had “a tendency to injure him in his office, profession, calling, or trade.”16 Soane’s brief aimed precisely at these two standards, claiming that the satirical poems were deliberately intended to embarrass Soane publicly and to damage his professional reputation, as the nature of their publication demonstratively proved:

We may fairly assume that [Soane’s designs] could have been attacked in a more serious way than by an anonymous publication of an abusive poem. All public disquisitions on the subject ought to be fair manly candid criticism, and not be holding a man up as an object of scorn and ridicule, to hunt down in his profession and degrade him in Society. In the first stated libel the language is ransacked for terms of scorn and derision, and Mr. Soane is held out to the Public as a man who has disgraced his Country. . . . As the censure is general the reader is left to presume that the work is execrable in toto.17

During the trial, Edmund Law, the counsel for the defense (who would later, ennobled as Lord Ellenborough, hear the case of 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields), argued that although Soane was indeed an “Architect of great merit,” the bank failed to exemplify his talents. Law proceeded to recite the poem line by line, substantiating each of its stinging slights with a comment on Soane’s design. He aimed to demonstrate that the satirical lines criticized specifically the architecture of the building, concluding that “as a public work, in which the national taste was to some degree involved, criticism ought to be entirely free upon it”; the bank was a “public performance” that, given its flaws, was a reasonable “subject of criticism, and even ridicule, provided that it was done in a fair, and manly, way.”18 Both parties emphasized the nature of the criticism—whether it was fair, manly, or candid—rather than its content, because the motivation of the defamatory statement would be evidence of libel, especially in a case where the truth or falsity of the libel could not be definitively asserted. In the case of “The Modern Goth,” whose very title was an accusation of barbarism, the distinction was measured upon an aesthetic plane, with verses that constructed parallels of architecture and personality: “Come, let me place thee in the foremost rank, / By Dulness, fated to deface the Bank; / By him, whose dulness darken’d every plan, / Thy style shall finish what his style began.” Was the intention of such lines to dismiss the architecture or to denigrate Soane? The judge admitted in his instructions to the jury “that architecture and all the other arts … were the subjects of fair criticism,” but he advised that the jury consider “whether that might be done … in a Poem, that was to hold up a man to ridicule all his life long.”19 Viewed in a broader perspective, it was up to the jury to consider the liabilities of two accusations of ugliness, one being the claim made by the verses that the architecture of the Bank of England was ugly, the other being the claim of Soane’s brief that the public scorn and ridicule was itself ugly. The jury’s subsequent half hour of deliberation and verdict of not guilty dismissed Soane’s libel suit and settled the proceeding in favor of the permissibility of the aesthetic critique of his architecture.

Figure 43. Indictment of the surveyor Philip Norris for a libel against John Soane.

But “The Modern Goth” episode would prove to be only the first of Soane’s encounters with defamatory publications. Critical letters, pamphlets, and reviews were attendants to his celebrity, and recourse to law became his instinctive response. During May and June 1821, three essays appeared in the Guardian, then a new weekly journal in which a correspondent referred to Soane and other architects by name in a promised indictment: “We have arraigned the state of contemporaneous Architecture, and unfortunately we have ample evidence to make out our case.”20 He attacked Soane directly, deploring the “vapid” and “uninteresting” designs submitted by the architect to the annual exhibition at the Royal Academy. Since Soane’s exhibits were “the Atlas of the Architectural fame of the Academy,” the author insisted, “No exertions should be spared to check the adoption of his manner. It is the most pernicious and vitiated. Nature, common sense, propriety, simplicity, are all immolated to his idol, Novelty.”21 Soane responded at once, attempting to discover the identity of the author and consulting acquaintances on the advisability of bringing suit against the Guardian. Two of Soane’s close friends recommended that he ignore these scurrilous attacks in order to avoid drawing further attention to the articles. One advised that he was “only paying the penalty, which all Public men are liable to, and which eminent, and successful men in particular, have always paid,” while the other, John Taylor, the editor of the Morning Post and the Sun, worried that the uncertainties of libel law would require Soane to prove the injury to his reputation by demonstrating that actual commissions had been lost, a burden of proof he could not meet. Obviously familiar with the legal criteria of libel, Taylor advised Soane “to treat it with contempt,” for if Soane were to lose, as in his first suit for libel, the publicity would compound the original insult.22

Very likely, the courts would have considered the Guardian commentary to fall under the category of criticism—critical commentary upon artistic works. Aesthetic criticism had long accompanied architecture and the arts, of course, but the dramatic increase in daily or weekly mass circulation newspapers and journals had fostered an equally dramatic increase in the quantity and timeliness of aesthetic criticism, which was eagerly consumed even or especially by readers who would not themselves encounter the buildings, artworks, plays, or books under critique. By the time the Guardian essays appeared in 1821, these critical commentaries on artistic work could not be cause for a libel action, even if they did occasion some loss of reputation. This principle had been set forward as legal precedent only several years earlier, in 1808, by a prominent libel case, Sir John Carr v. Hood and Sharpe, which heard an author’s claim against booksellers who had published a pamphlet satirizing his works. The judge for the case was none other than Lord Ellenborough, serving as chief justice. In Carr v. Hood, he stated in his charge to the jury that all artistic works placed before the public were susceptible to “fair and candid criticism, which every person has a right to publish, although the author may suffer a loss from it. It is a loss, indeed, to the author; but is what we call in law Damnum absque injuria; a loss which the law does not consider as an injury, because it is a loss which he ought to sustain. It is, in short, the loss of fame and profits, to which he was never entitled.”23 The only restraint against such criticism, albeit one that Lord Ellenborough firmly asserted, was that it not deride the personal character of the author, except insofar as he “embodied” himself in his work.24 The law, in other words, distinguished between character and reputation, the former being the private moral composition of an individual and the latter his public representation, which was, at least in the case of an architect, artist, or writer, subject to public judgment. Lord Ellenborough went on to assert the positive value of such criticism in identifying and suppressing undeserving artistic productions: “It prevents the dissemination of bad taste, by the perusal of trash; and prevents people from wasting both time and money.”25 Here Lord Ellenborough was recapitulating a point he had formulated in 1799 as defense counsel in Soane’s action against Norris, where he had argued that “ridicule, while it was applied to public works ill executed, was of admirable use to mankind; for it operated to keep in the shade unmeaning dulness, instead of her coming forward with her languid spirit and shapeless figure to obtrude herself among the Muses and the Graces.”26

The Guardian correspondent endorsed this view of the role of criticism; in his third essay he acknowledged without regret that his comments had “given mortal offence” and inserted implicit references to Soane as he denounced the threats of prosecution for libel that had followed his first installments. “To those who, in the pride of their reputation, or in the confidence of their wealth, boldly and unceremoniously talk of disarming Criticism by indictment, we hold a very different language. . . . That anyone who has gone ‘right onwards’ to wealth and honor, doubtless with a large assistance from the panegyric of the press, should talk, not of argument, but of prosecution when criticism dares to be what it ought, to think for itself, and to speak boldly, whether its object be an R.A. or one unknown to Fame … this, indeed, is monstrous.”27 No legal claim, he continued, may be made against honest criticism “which abstains from personal insults, and forgets the man while it condemns the Artist”—a careful distinction that revealed the author’s awareness of the relevant legal standards.28 The critic would not submit himself to a court of law, but only to the same tribunal of public opinion in which he had arraigned the architects: “If we are prejudiced, arrogant, unjust, and ignorant, the public will decide against us. . . . We laugh at the threats about prosecution; and the public shall laugh too, when we discover a serious attempt to set up attorneys and special juries into ‘arbitri elegantiarum’ in the last resort.”29 Soane apparently conceded this aspect of his critic’s argument and turned to the medium of the press to submit his own case to the public. Two letters that, given John Taylor’s proprietorship, must have been written with Soane’s assistance or consent soon appeared in the Sun. The first condemned the Guardian critic for his ignorance of architecture and the inconsistency of his arguments, which were inexplicable and unconvincing in light of Soane’s “acknowledged eminence” and “most intimate and extended knowledge of his art.”30 The second reproached another journal, the Magazine of Fine Arts, for approving the “impudent and malevolent” Guardian essays as informed and impartial.31 This epistolary defense placed less emphasis on the rebuttal of architectural discernment and more upon the unassailability of Soane’s professional stature; it emphasized, in other words, the persona over the embodiment.

The publicity surrounding the Guardian essays subsided, but the episode was not Soane’s last encounter with scurrilous publications or with the pursuit of libel claims. On June 12, 1827, the Court of the King’s Bench heard the case of Soane v. Knight. Soane, apparently against the advice of counsel, had brought a charge against the publisher of Knight’s Quarterly Magazine for printing three years earlier a lengthy satire of Soane titled “The Sixth, or Boetian Order of Architecture.”32 Like “The Modern Goth,” this new satire mocked the novelties and idiosyncratic aspects of Soane’s architectural work, sarcastically categorizing them as a Boetian Order (a reference to the classical characterization of the inhabitants of Boetia as a dull and foolish people inferior to their Athenian counterparts) on account of disproportion of columns and pilasters, discordance of parts and whole, and hanging arches “miraculously suspended by the back, like the stuffed crocodile on the ceiling of a museum.”33 Following arguments, the recitation of the offending essay, and the judge’s instructions, the jury “immediately” found for the defendant. Given the legal standards outlined in the previous incidents, the verdict could not have come as a surprise. Soane’s counsel attempted to portray the public ridicule of the satire as evidence of the critic’s “private pique and malice,” but the counsel representing the defendant responded by citing Lord Ellenborough on the permissibility and importance of aesthetic criticism and the idea that such criticism tended to the improvement of society by raising up works worthy of acclaim and exposing those deserving of ridicule.34 “It was,” argued the defense counsel, “the undoubted right of the press to endeavour to correct the public taste, and to explode by argument or ridicule all false notions and erroneous works,” and this regulatory function was all the more vital in the case of an architect, “whose works, like his materials, are lasting, and who covers a metropolis with them.”35

Adding to the obvious injuries inflicted on Soane by the trial—the evidentiary recitation of the libelous text and its reproduction in newspaper accounts, and of course the failure to win a legal defense of his reputation—was the fact that the proceedings were held in a building of his own design, the New Law Courts at Westminster Hall. (Figure 44) During the construction, Soane had already endured the examination of his design by a parliamentary Select Committee convened to question his decision to append a neoclassical front to the existing gothic fabric. He was ordered to demolish part of the work already under way and provide a more congruous addition. Soane defended himself with a report submitted to the House of Commons that outlined the many checks upon his work, but this only furthered the extensive accounts that appeared in newspapers about the affair. During the 1827 libel trial, Soane had to hear the opposing counsel’s superfluous addition of his own animadversions upon the design of the Law Courts: “With all respect to Mr. Soane, I confess that I do really think that he has made a mistake in these courts of justice … I assure you I was nearly killed in the passage in getting into the court, so ill-contrived, as I think, are the passages.”36

Figure 44. A plan drawing, partly by Soane himself, for the design of the new Law Courts at the Palace of Westminster. Soane Office, Sketch of a Design for part of the New Law Courts at Westminster (ca. 1822–30).

Through the decades-long course of Soane’s several encounters with aesthetic commentary, the judgment of ugliness enacted a precipitating role rather than a concluding one. His career included successes and failures, and no one of the critical judgments had a fatal repercussion, but they precipitated a sequence of differentiations and identifications bringing the aesthetic register into new relations with circumstances outside of architecture. By prompting what was ultimately a detour through the institutions of the court and through the changing mechanisms of libel law, the judgment of ugliness led to the distinction or separation of aesthetic criticism, to its depersonalization, in a direct sense, and therefore allowed for its layering onto other planes of social transaction, such as the professional or the political. A judgment of beauty, of course, would not have prompted any such recourse to law or seeking of remedy; it was the serial assessments of dullness, distaste, disproportion that pressed the aesthetic toward the legal and thence toward the social. Soane’s scrap-books of newspaper clippings give palpable evidence of his concern for, and his attempt to bring to bear some personal control over, the public sphere made concrete in the ever-accumulating pages of newspapers and journals. The scrapbooks document his broad curiosity in diverse subjects and events, from the Napoleonic Wars to experiments in electricity, and throughout his attention to the cultivation of reputation is clearly evident. Among the clippings can be found dozens of reports of sundry types of libel trials—from defenses of professional competence to defenses of women’s honor—that clearly suggest a more than abiding interest. (Figure 45)

Figure 45. Newspaper report of a case for the prosecution of a libel against the memory of the late Caroline Lady Wrottesley, one of many reports on libel cases preserved by Soane in his scrapbook of newspaper clippings.

Criticism

Resolved:

That no comments or criticisms on the opinions or productions of living artists in this Country should be introduced into any lectures given at the Royal Academy.37

On February 11, 1810, a correspondent for the Examiner reported with indignation upon a “preposterous assumption of privilege from critical animadversion.”38 The privilege to which he objected was a resolution forbidding criticism within the Royal Academy of any living artist in Great Britain, a regulation pointedly directed at the academy’s own professor of architecture, John Soane, who was obliged by his post to deliver six lectures each year to the students of the Royal Academy. The lectures were held less frequently in practice and were notable events, attended by academicians and invited members of the public as well as the students. The obligation of the professors to deliver lectures was stipulated in the Founding Instrument of the Royal Academy, signed by King George III in 1768 to grant royal patronage and hence public sanction to the body of artists. It specified the structure of governance for the Royal Academy (consisting of a Council and a General Assembly) and also included strictures upon the demeanor of the academicians. The very first clause stated that the Royal Academy should be composed of artists “of fair moral character, of high reputation in their several professions.”39 Speaking on January 8, 1810, Soane quoted directly from the Founding Instrument to describe the purpose of his lectures: “And amongst the laws of this Institution it is declared that, ‘There shall be a Professor of Architecture who shall annually read six lectures, to form the taste of the students, to interest them in the laws and principles of composition, to point out to them the beauties or faults of celebrated productions, to fit them for an unprejudiced study of books, and for a critical examination of structures.’ ” Required to develop the knowledge and discernment of the students by exposing them to the history and principles of architecture, Soane would necessarily have recourse to the detailed discussion of architectural examples in his lecture. He was therefore forced to caution his audience that “if in the endeavour to discharge the duties of my situation, as pointed out by the laws of the Institution, I shall be occasionally compelled to refer to the works of living artists, I beg to assure them that, whatever observations I may consider necessary to make, they will arise out of absolute necessity, and not from any disposition or intention on my part merely to point out what I may think defects in their compositions.”40 Soane, already keenly sensitive to the nature of criticism, was evidently alert to the need for propriety in the institutional context of the Royal Academy, whose members were, by the definition of its charter, to be considered accomplished artists who merited their high reputations.41

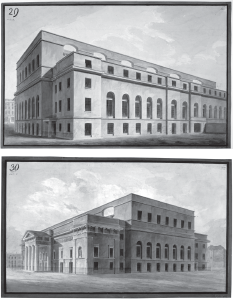

On the evening of January 29, 1810, Soane delivered his fourth lecture, on the topic of the relationship between parts and the whole, employing drawings to illustrate his points. Proceeding to a discussion of buildings that failed to resolve into unified form, and as an example of the undesirable practice seen “in many of the buildings of this metropolis” of embellishing one facade at the expense of the others, he placed before his audience two illustrations of the side and rear facades of the recently completed Covent Garden Theatre by the young architect Robert Smirke: “These two drawings of a more recent work point out the glaring impropriety of this defect in a manner if possible still more forcible and more subversive of true taste. The public attention, from the largeness of the building, being particularly called to the contemplation of this national edifice.”42 (Figures 46 and 47) Soane’s derogation of the architecture of a fellow academician—Smirke, then thirty years old, had been elected to the Royal Academy two years earlier—startled his audience, many of whom hissed in protest. Soane had obviously anticipated the effect of his remarks, for he immediately added: “It is extremely painful to me to be obliged to refer to modern works, but if improper models, which become more dangerous from being constantly before us, are suffered, from false delicacy, or other motives, to pass unnoticed, they become familiar, and the task I have undertaken would be not only neglected but the duty of the Professor, as pointed out by the Laws of the Institution, becomes a dead letter.”43 Having thus echoed Lord Ellenborough’s reasoning, he then proceeded to recite once again from the Founding Instrument the “laws of the Institution” that obliged him to offer such criticisms for the edification of the students. Soane intended his two illustrations to show the marked contrast between the front facade, already more simple or grave than many had expected the new theater to be, and the unadorned sides and rear, whose scale and plainness suggested a warehouse rather than a civic building. The omission of adjacent buildings exaggerated the effect of an overwhelming dullness. Motivated by spite toward Smirke as much as by pedagogical intention, Soane’s criticism was by some judged to be the uglier aspect of the affair. The Royal Academy responded quickly to his provocation; within the week, the council met and drafted the resolution that prohibited any “comments or criticisms on the opinions or productions of living artists in this Country” to be introduced into lectures.44 Soane answered that this unacceptable condition would force him to suspend his course of lectures, but the General Assembly ratified the council’s resolution nevertheless, with only one member voting in dissent.

Figures 46 and 47. Illustrations of Robert Smirke’s design for the new Covent Garden Theatre, used by Soane in his Royal Academy lecture. Soane displayed the illustrations, showing the front, rear, and side elevations of the building, to exemplify how subordinate facades may appear diminished and utilitarian due to their lack of ornamentation, an undesirable outcome in civic architecture.

The broad resolution prohibited even “comments” upon any aspect of an artist’s work, whether the actual productions of an artist or his “opinions” expressed in another medium. Obviously intended to maintain a presumed propriety in the affairs of the academy, it resulted in part from some members’ personal antipathy toward Soane. But the resolution was undoubtedly also a reaction against the severe partisan criticism that circulated in newspapers and reviews outside the academy; each year, the annual exhibition exposed individual academicians and the Royal Academy itself to the juridical determinations of the press. In a period before illustrated newspapers and journals, criticism often circulated more widely than the paintings or sculptures it addressed; even architecture, more visible to the course of daily life in London, was depicted textually to a large audience who remained unacquainted with the actual works.45 The members’ experience of the exhibition reviews undoubtedly swayed many of them in favor of the ban, which promised to maintain the academy as a sanctuary in which one’s “high reputation,” the first of the criteria of membership, would never be impugned.

But while a large group of academicians had reacted adversely to Soane’s comments, others agreed that the instruction of students required such criticisms and expressed their support privately, in correspondence and in social meetings. Soane solicited further sympathy by privately circulating a lengthy pamphlet titled “An Appeal to the Public: Occasioned by the Suspension of the Architectural Lectures in the Royal Academy,” which presented his defense in a didactic brief, with more comments on the Covent Garden Theatre and arguing that criticism was necessary to prevent the propagation of bad taste through poor examples. Public support for Soane’s position appeared in the pages of the Examiner, whose correspondent strongly opposed any constraint upon fair criticism, seeing it as vital for the development of architecture. A reader concurred in a letter to the editor, objecting to the “disgraceful” law, and declaring “criticism upon the Arts as necessary to their preservation and improvement, as the liberty of the Press is to preserve the freedom and promote a moral state of society.”46 This rhetorical figure—criticism as the improvement of society through the disciplining of taste and the opprobrium on ugliness—had been the basis for the legal defenses against libel, including of course the episode of “The Modern Goth,” in which Edmund Law had rebutted Soane’s charges by contending that criticism “kept dullness in the back ground, instead of stalking forth in the glare of public light.”47 Later, as chief justice, he would rule that “liberty of criticism must be allowed, or we shall neither have purity of taste or morals. Fair discussion is necessary to the truth of history and the advancement of science.”48 Soane now drew upon the same argument and defended his own criticisms by reasserting the claim he made when commencing his lectures, that he was motivated only by a sincere desire to improve architecture especially in such “works where in a great degree the national taste is implicated.”49

The conflict formally ended in 1813, seemingly through the mutual exhaustion of the antagonists; the Assembly passed a statement regretting that Soane had taken personal offense at a law that was intended to apply generally, and an appeased Soane recommenced his lectures. But the question of criticism, like the resolution itself, had not been withdrawn. In March 1815, Soane ended the final lecture of his series by quoting the closing lines of Alexander Pope’s 1711 Essay on Criticism, thereby claiming for himself, rather implausibly, Pope’s attitude of a selfless, disinterested critic pursuing only the truthful “knowledge and love of architecture.”50 But by Soane’s time, criticism, invariably accompanied by some disapproval, had already passed through the pages of Richard Steele’s Tatler and Joseph Addison’s Spectator and through the voluminous work of Samuel Johnson, to become a staple of the public discourse transacted in the competitive press of London. Soane’s invocation of Pope, however sincere, was well out of date. Yet Soane perceived the timely role for criticism to be prompted by the very fact of architecture’s public role in civic life, and the special urgency of his criticism of the Covent Garden Theatre, which he endeavored to show in as unflattering light as possible within the format of a Royal Academy lecture, to be due to “public attention, from the largeness of the building, being particularly called to the contemplation of this national edifice.”51 This same point would of course be directed against Soane in the 1827 libel trial, when the counsel for the defense had argued that only a book or building “that can stand the but [sic] of ridicule becomes immortal, for that which ridicule can put down ought to be put down. If this remark applies to books, still more does it apply to the artists whose works, like his materials, are lasting, and who covers a metropolis with them.”52

The visibility and presence of architectural ugliness—of the palpable eyesores of the metropolis—conflated and collapsed otherwise differentiated social trajectories, the lives of real persons, the changing standards and predilections of taste, and the evolving legal regulations of common law. In condensing these, architectural ugliness also participated in the novel reconstitution of architect and subjectivity, in effect depersonalizing the sentiments of taste and refashioning them as social instruments, calibrated by conventions of criticism and by mechanisms of libel law. While the most notable judgments may have predictably pertained to buildings of national significance such as Soane’s Bank of England or Smirke’s patent theater in Covent Garden, these were not exceptions, but rather part of a broader assessment of the physical monuments of civic life. When Soane, Smirke, and their contemporary John Nash were appointed architects to the Board of Works to advise on the building program of the Church Commissioners, they joined an effort to construct a multitude of churches for a minimum outlay of expense. With a budget of no more than twenty thousand pounds per building, the architecture of each was inevitably impoverished to some degree, even as it would just as inevitably be the focus of public scrutiny. One of Nash’s designs, All Souls, Langham Place, received perhaps the most scathing derision in the House of Commons, when Henry Gray Bennet rose to say that “it was deplorable, a horrible object, and never had he seen so shameful a disgrace to the metropolis. It was like a flat candlestick with an extinguisher on it. He saw a great number of churches building, of which it might be said, that one was worse than the other. . . . No man who knew what architecture was, would have put up the edifices he alluded to, and which disgusted every body, while it made every body wonder who could be the asses that had planned, and the fools that had built them.”53 Parliamentary privilege protected Bennet from any potential repercussion—statements made in the House of Commons were exempted from prosecution for slander—but in any case the notable aspect of his obloquy was the explicit absence of Nash’s name, with Bennet wondering who could have been the person responsible for such architecture.

Figure 48. George Cruikshank, “Nashional Taste!!!” (1824).

More curious, and perhaps more perceptive, was the caricature that the incident inspired George Cruikshank to draw. (Figure 48) His drawing shows Nash balanced uncomfortably upon the spire of All Souls, his posterior impaled upon its tip, carrion birds above and a vein of London smoke behind. The caption aligns Cruikshank’s image with Bennet’s disdain for the asses who had planned the new churches: “Providence sends meat / the Devil sends cooks—/ Parliament sends funds—/ But, who sends the architects?—!!!” Relevant too is the punning title of the drawing, “Nashional Taste,” whose obviousness should not obscure the fact that it presumes, even fosters, the collapsing of the imagination of an individual architect into a collective perception that in turn is equated with a civic standard of judgment and a civic aesthetics. It enacts the depersonalization of taste and the disembodying of the architect from his work (even as the image places his body in extremis). Cruikshank’s drawing, in other words, seen in relation to the architectural object of All Souls on the one hand and the verbal or textual object of Bennet’s obloquy on the other, is a succinct portrayal of the operation of criticism at this moment. It is a summative answer to the unasked question of how architectural ugliness might be discussed, instrumentally and consequentially, in the public sphere.

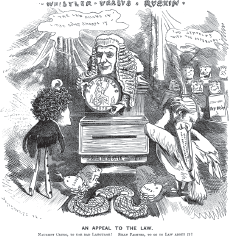

The novel constructions of aesthetic criticism formulated through these events and set forward in libel rulings at the beginning of the century gained substance as legal precedents over the decades. They did not, however, forestall further libel trials, including one of the most famous, Whistler v. Ruskin, held near the century’s end. Incensed by John Ruskin’s scathing critique of his Nocturnes, the artist James McNeill Whistler brought suit for libel. The trial in 1878 received extensive attention in the pages of journals and newspapers, enabling, just as in Soane’s cases, the incessant repetition of the alleged libel, Ruskin’s dismissive likening of Whistler’s artworks to “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.”54 Following by now well-established precedent, the judge instructed that fair criticism of Whistler’s art was permitted by the law, but that insults to the artist as a person were libelous. After deliberations, the jury returned a verdict in Whistler’s favor, deeming Ruskin’s statements a libel, but awarded damages of only one farthing, a token amount whose insignificance indicated a sense that both critic and artist were wronged by the legal proceedings that followed from the initial publication. (Figure 49) But if such criticisms of the aesthetic value of architectural works had acquired a considerable degree of immunity from claims for libel, published statements that questioned professional competence did not. Harm to an architect’s reputation might result from the disparagement of his completed works, but that reputation could suffer even more from insinuations that he was not good at his job. Daily newspapers did not give to the case of Botterill and Another v. Whytehead the attention they had given to Whistler v. Ruskin just a year before, but the case was reported in professional architectural journals. An architectural firm had lodged the claim against a vicar who had sent a communication to a neighboring parish urging them not to hire the firm for planned restorations of a church. The vicar had claimed the architects were not sufficiently knowledgeable in the work or in their religion, claims that the plaintiffs would argue insulted their professional character and damaged their business. The court finding “evidence of express malice” in the vicar’s statements, the architects won their claim and were awarded fifty pounds in damages by the jury.55

Figure 49. “An Appeal to the Law.” A cartoonist for Punch mocked both the “Naughty Critic” and the “Silly Painter” for their respective responsibility in bringing about the libel case.

By the middle of the twentieth century, a moment when modernism was becoming widespread but had not secured the broad approbation of public taste, architecture remained susceptible to ridicule in terms not far removed from those familiar to Soane or Nash. The aesthetic and linguistic vocabulary was different, but the judged failing of an architect to recognize a manifest ugliness remained a distillation of critical comment. Architectural critics, by now a recognized profession of their own, diagnosed the difficulty as a distance in understanding between architects and the lay public that corresponded to a distinction between the appearance of a building and the many contextual intricacies of its construction and use. Using the example of the lengthy official debates over the proposed plans for a large new building in Piccadilly Circus, Reyner Banham explained that the “general public was therefore baffled to find that what it thought was simply a straightforward argument about an ugly building seemed to be largely concerned with matters like illuminated advertising in Latin America, underground pedestrian circulation, shopping habits in Coventry … and other matters that seemed not to have even marginal bearing on the appearance of the building.” The solution, he suggested, was to solicit more “responsible and informed criticism from the lay side,” which had disappeared, Banham thought, in Ruskin’s day.56

Along with Banham, a number of architectural journalists and editors in Great Britain expressed their concern that the criticism of architecture was insufficiently rigorous, that it was in fact rarely critical. Beginning in 1948, J. M. Richards, one of the editors of the Architectural Review, began to express the conviction that although an exacting criticism of architecture was an urgent necessity, it was constrained by fears of libel: “There is, however, one practical difficulty to be overcome: the law of libel, which applies more stringently to architecture than to the other arts because of the large amount of someone else’s money involved. . . . In criticizing an architect’s work it is often difficult to draw the line between what is merely an opinion on his merits as a designer and what is an opinion on his competence to handle—or incompetence to mishandle—a client’s or a company’s funds.”57 The continuing confirmation of the standard of libel as requiring the distinction of architect from architecture had, according to Richards, come to forestall the possibility of matching the critical attention that prevailed in other arts. As a remedy, Richards speculated that more “frank architectural criticism” might arise “if there were some system of inviting criticism when a building was completed. . . . Following the precedent of the first night ticket sent to the dramatic critic and the book sent to the reviewer, which were an invitation to criticise.”58 Whether such a process could be installed, and whether it would lead to a new critical freedom, was a question he deferred to “the legal experts.” But without such a process, he predicted a continuation of a harmful mediation of architectural discourse: “Any attempt at seriously criticizing buildings, since it takes on the character of an unwarranted attack, creates a resentful critical climate in which reasonable discussion is most difficult. As elsewhere, the law of libel chiefly operates not when it is really applicable but through the atmosphere of caution it engenders.”59

Though less frequently pursued than in Soane’s day, the threat of libel action has not disappeared from architectural discourse, even today. In late summer 2014, reports that the London-based architect Zaha Hadid was suing the critic Martin Filler for defamation were met with considerable surprise. In an essay titled “The Insolence of Architecture,” ostensibly a book review and published in the New York Review of Books, Filler denigrated Hadid’s work—“poorly conceived and questionably executed” is one illustrative phrase, “experimental showpiece” is another—and denounced also what he described as her “imperious” manner, accusing the architect of unconcern for the conditions of laborers who were to construct her architectural designs in places like Qatar.60 News of the essay, and its most pointed passages, circulated through architectural media. But once Hadid herself responded to the essay with a lawsuit filed in a New York State court, Filler’s essay, its assertions, and Hadid’s reaction all became the subject of considerable interest for architectural and popular media.61 The retaliatory lawsuit seemed to startle media audiences more than Filler’s accusations. Why would an architect, secure in her international reputation, resort to a lawsuit to reply to the commentary of an architectural critic? Was not vituperative criticism simply the collateral cost of celebrity in the twenty-first century? Was not her architecture, especially in its most public manifestations, legitimately subject to the scrutiny of media? Such questions are evidence of a contemporary acclimation to the media environment of modern architecture, with the lawsuit received as a seemingly novel challenge to that structure.

The particular transgression in the recent case, according to the architect’s brief, was Filler’s assertion that Hadid had expressed unconcern over the deaths of workers in the construction of her work in Qatar and that she had disowned responsibility (which Filler implied she bore) for those deaths. In addition, the brief stated, Filler had presented an ad hominem attack, a defamatory criticism of Hadid herself rather than her work, or her embodiment within her work. Indeed, in this instance, it would be more properly characterized as an ad feminam attack, given the explicitly gendered nature of criticism to which Hadid was subjected. In addition to noting her “imperious manner,” Filler also referred to her as “hard-hearted Hadid”; such phrases followed the example of any number of other critics who had derided Hadid’s personality in similar manner and who all too frequently focused upon ridiculing her physical appearance as part of their critique. The result of the libelous article, the brief concluded, was that Hadid had been “impugned … in her profession as an architect” and was “exposed … to public ridicule, contempt, aversion, disgrace, and … evil opinions of her in the minds of right-thinking persons.”62 The audience of architectural discourse gathered quickly into camps for each side: either Filler had been justified in denouncing the political ramifications of Hadid’s work and her stated unwillingness to acknowledge them, or Filler had offered clearly misleading representations of Hadid’s public statements in a deliberate effort to damage her reputation. While public opinion continued these rounds of debate, the protagonists settled out of court, with Filler offering an apology appended to the subsequently revised article and undisclosed damages that Hadid promised to donate to an unspecified charity in support of laborers’ rights.

The surprise with which the case was met—surprise that Filler (or more, his publisher) would have presented such a scathing critique, and surprise that Hadid would respond with a suit for libel—should in fact have been no surprise at all, for both were predictable continuations of the trajectory along which public criticism and judgments of architectural ugliness were at first linked to and then separated from criticism of individual architects in the novel formulations of English libel law that emerged at the start of the nineteenth century. From those origins, moving along the course of professionalism in which an architect’s reputation assumed the different and more concrete forms of artistic ability and technical competency, such critiques led to the loosening of the aesthetic register of architecture from its other dimensions, as well as to the sharper definition of the embodiment of the architect as a persona rather than a person. It was the pointed and personal nature of judgments of ugliness that prompted legal redress initially and gave particular purpose to the new instruments of libel law, and it is the nature of judgments of ugliness that remains the test of those instruments even now.