Chapter 6

The Profession

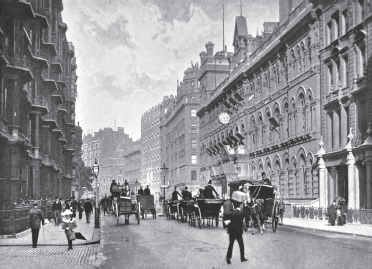

Writing in 1888 for Oscar Wilde’s magazine The Woman’s World, the novelist Ouida gave an unambiguous assessment of the streets of London: “To drive through London anywhere is to feel one’s eyes literally ache with the cruel ugliness and dulness of all things around.”1 From the insufficiency of street lighting to the vulgarity of advertising hoardings, the meanness of the streets, and, above all, the awfulness of building exteriors, the city offered the resident or visitor navigating its streets only an unrelenting ugliness. “London,” she wrote, “has been ill and unkindly served by the innumerable architects, engineers, and Boards of Works who have worked for it.”2 Responding to Ouida in the Pall Mall Gazette, the designer William Morris offered his agreement: “There is, indeed, as Ouida says, something soul-deadening and discouraging in the ugliness of London; other ugly cities may be rougher and more savage in their brutality, but none are so desperately shabby, so irredeemably vulgar as London.”3 Both wrote about the ugliness of the city not as occurring in a moment of emphasis, in a single building or monument, but as a generality, a quality diffused across the metropolis, much like an atmosphere. (Figure 50) The physical atmosphere was indeed one aspect of experience of the ugliness; Ouida listed atmosphere and climate as possible causes—“Is the cause atmosphere, architecture, national temperament, climatic influences, insular melancholy, or what is it?”—and Morris for his part made effective use of the analogy of smells to convey the sensation provoked by the ugliness of London: “There are certainly smells which are more depressing and deadly to pleasure than those which are frankly the nastiest: the refuse of gasworks, the brickfields in the calm summer evening, the faint, sweet smell of a suspicious drain, the London wood pavement at two o’clock on a hot, close summer morning—these kinds of smells are more lowering than the kind of stench that drives one to write furiously to the district surveyor. And the quality of London ugliness is just of this heart-sickening kind.”4 As with the difference between disgust and irritation, ugliness here was a smell that did not prompt one to action—with a letter to the district surveyor—but annoyed without surcease. Though many aspects of metropolitan life reinforced the ugliness, the monotonous effect of architecture was, for Ouida, centrally to blame for a city of “buildings constructed without an idea, without a meaning, without a single grace, without any charm of light and shade, of proportion or of form—repeating its own nullity, again and again and again, as an idiot repeats its mumbling nothings.”5 This monotony Morris was inclined to attribute not to insular melancholy but to a legislative cause: the Metropolitan Building Act of 1844.

Figure 50. Victoria Street, the first of several new streets opened through the city in the program of metropolitan improvement of the second half of the nineteenth century. Opened in 1851, it was fully built up by 1895 (when this photograph was taken) with frontages typically of considerable length, contributing to the scale and appearance of the buildings judged harshly by Ouida and Morris.

Morris accused this legislative device, which imposed building standards upon the city to be enforced by newly appointed district surveyors, of having stifled the inventiveness of architects in favor of the repetitions of a degraded architectural consensus. The very success of the Metropolitan Building Act in imposing a rule upon the city was in Morris’s view its failure, with ugliness its consequence. He called, in remedy, for its repeal. While this action might have permitted a range of experimental freedoms for the builders and architects of the city, the law was not the only manifestation of the underlying metropolitan purpose that Morris diagnosed as the sickness of London. That purpose was commerce, and it too had an aesthetic consequence. “The monstrosity we call London … is at once the centre and the token of the slavery of commercialism which has taken the place of the slaveries of the past. . . . The sickening hideousness of London, the metropolis of the nation, which has worked out the sum of commercialism most completely seems to me a mark of disgrace.”6 If commercialism was, as Morris claimed, connected to the consequence of metropolitan ugliness, then the Metropolitan Building Act was only one of the mechanisms of architectural normalization that mediated economic practices and aesthetic performance.

An Average Profession

Other such mechanisms of architectural normalization proliferated during the decades that preceded and followed Morris’s essay, from the beginning to the end of the Victorian period. Along with legislative devices such as the Metropolitan Building Act, the smoke abatement statutes, and laws mandating infrastructural improvements, new protocols emerged to regulate the practice of architecture. In January 1837, only a few months before Queen Victoria would ascend to the throne, the Privy Council granted a Royal Charter to the Institute of British Architects, founded three years earlier for the purpose of “the general advancement of Civil Architecture, and for promoting and facilitating the acquirement of the knowledge of the various arts and sciences connected therewith.”7 A Royal Charter enabled incorporation, or the conversion of a group of individuals into a single legal body with rights under law, and the significance of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) lay in its translation of the practice of architecture from the discrete activities of individuals into a professional body of architects.8 The membership of the RIBA remained quite limited for much of the nineteenth century, with many architects practicing outside of and with no relation to the institutional body. But it nevertheless influenced directly the development of standards of practice, from fees to contracts to codes of conduct—in short, the elements of the profession. Controversies developed, first over the question of architectural education as earlier customs of apprenticeship gave way to formal academic training, and then over the question of examination and registration, with advocates in favor of regulating the practice of architects for the benefit of the public and opponents defending the inscrutability of artistic skill. A Registration Bill presented in Parliament in 1891 brought these arguments onto the pages of the Times and other newspapers. By the end of the century (and of the Victorian period) the standing of architectural practice was largely established, the RIBA membership having grown to the extent that it could reasonably claim to represent the profession, and in 1931 the Architects Registration Act formally concluded the century-long establishment of the architectural profession.9

Architectural discourse during the Victorian period consisted of sustained polemics on style, including the debates between neoclassicists and gothic revivalists, the architectural evangelism of the Ecclesiologists, and arguments over the practical accommodation of the new building programs that emerged with industrialization. But alongside this overtly aesthetic discourse were equally contentious arguments about the nature of the architectural profession, and, as Ouida and Morris suggested, the state of the profession was not unrelated to the state of civic aesthetics. In a century consumed by business, matters of ethics, fairness, and propriety possessed an urgent relevance to economic life, and an ugliness in architectural appearance might be mirrored by an ugliness in professional behavior. A few years before Ouida and Morris lamented the ugliness of London, architects and men of business were expressing their concern over a case—undoubtedly one of many—of professional misconduct. A Mr. George Artingstall wished to enlarge his house, but having retained architect and builder and paid them to proceed with the work discovered the result to be shoddy and not in accordance with the agreed specifications. Artingstall’s legal action against the builder and architect and their countersuits against him and each other were referred by the courts to legal arbitration and there settled in his favor.

This case led the British Architect to publish a lengthy reflection on the worrying indication of lacking professional propriety and a corresponding lack of public regard for the architectural profession. The journal presented its readers extracts from testimony, details of the specifications, an analysis of the bill of legal costs, and correspondence sympathetic to Mr. Artingstall. Among the latter, one correspondent regretted that the “profession of architecture unfortunately does not possess any fence through which admittance must be obtained by the prospective practitioner, or through which the unworthy can be expelled.”10 The journal agreed with the opinion that the profession required protocols and habits as well for elevating its standing as a body, and proclaimed itself dedicated to “the purpose of propagating and defending the interests of the architectural profession in Great Britain.” To this end, it endeavored to “analyze and expose every discovered weakness, error, or wrong, whose existence endangers the reputation and progress of the Body; either from without or from within.”11 Efforts to establish the norms of professionalism—education and training, examinations, codes of conduct, and the like—were efforts to guarantee an ethical probity and assume a moral standing during a period in which those qualities became valuable currency in the economic processes of the metropolis. Although these qualities could still be located in, or deemed absent from, an individual person, they were through the rise of professionalism increasingly attributed to a corporate body, to the profession of architecture.

The stylistic developments of Victorian architecture and the professional consolidation of Victorian architects are two strands of a historical narrative, both attended to by the accounts of architectural history, but the instrumental relationship that existed between these two strands has only been hinted at. The recognition of Victorian architecture by architectural history began almost bemusedly in the 1930s and then with a grudging seriousness in the two decades that followed.12 Recognition, though, was tempered by a frank willingness to pronounce the architectural uncertainty and irresolution of a professional discourse that had been disoriented by its unremitting experiments with styles and the unmitigated pragmatism of some of its practitioners. The architect H. S. Goodhart-Rendel, who served as president of the RIBA and who spurred the historical interest in Victorian architecture, could nevertheless readily describe one of his Victorian predecessors as “not a man to get architecture right” and “incapable of producing a decent building of any kind.”13 Other nineteenth-century architects received complimentary assessment, but rarely without qualification. Delivering a lecture upon possible candidates for preservation in 1958, Goodhart-Rendel included the Liverpool Sailors’ Home and the London Coal Exchange: “I do not rate highly the aesthetic value of either, but their historical and associational value is intense: After all, neither is as ugly as Stonehenge.”14

This ambivalence was continued by John Summerson, who elevated it from connoisseurial opinion to historical analysis. Having proposed that there was in nineteenth-century Britain a “singular attraction on the part of some painters, architects, and writers towards ugliness,” he went on to survey the work of the architectural class that produced Victorian London, taking recourse to a variety of colorful terms, including “mediocrity,” “shoddy,” “hasty and vulgar,” “destructive and horrible.”15 Any period survey nominates highs and lows, but Summerson’s accounts of Victorian architecture emphasized its typically middling achievement, which reflected architecture’s participation in a prevailing social order to which “home life and making money were so very much the most important things.”16 Designed largely by “practitioners of a lower order of talent,” the architecture of the civic realm of London was consequently “pretty crude,” elevated by neither patrons’ money nor designers’ skill.17 The outward judgment cast by Morris and Ouida was from this perspective correct, but Summerson had his own interpretation of its significance, to add to Ouida’s (emotional temperament) and Morris’s (commercialism). Victorian architecture was, in a manner both simple and complex, “in its own time and in the eyes of its own best-informed critics, horribly unsuccessful.”18 “It was felt by many at the time to be a failure, declared by some to be a failure, and received by the next generation as a failure.”19 Summerson’s historical judgment, in other words, was not a novelty, but a continuation of the self-perception of the Victorian period itself. And crucially, what is judged in this assessment is not, or not only, the individual works of individual architects, but the collective production of the profession. The author of ugliness is not the architect, as a person, but the architect as a corporate body.

The Death of the Architect

The life of the individual architect is of course made up of different consistencies and events than that of the corporate body. The life of the individual architect need not parallel exactly that of the corporate body, rather the two intersect in moments and routinely diverge. It is common, for example, for a corporate practice to dissolve while its individual members continue their careers, or conversely for it to continue in the absence of one or more of those individuals. Very likely, that absence is due to the death of the individual body, the individual person, the cessation of a trajectory of architectural production. The familiar conceit of the death of the author, only a half century old, has accustomed readers, or users, of cultural productions such as architecture to the possibility of a segregation of a biographical life from the cultural objects that it previously summoned.20 This figural manifestation then opens into that concept of textuality in which intention, significance, and meaning are fully diffused among the biographical fragments of a life lived, disassembled and reassembled as interpretation, proposition, or possibility until the author as such has faded almost entirely from view. But the familiarity of this figurative death of the author (who may be writer, artist, architect) should not encourage one to overlook its accompanying literal manifestation, the actual death of an author, and to inquire into its consequences for, among other things, the determinations of aesthetic value.

One such death occurred on August 17, 1969; the person in question was architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Mies—widely known even during his lifetime by his abbreviated surname—was eighty-three years old, forty years on from his radical design of the Barcelona Pavilion, thirty years on from his arrival in the United States, ten years on from the completion of the Seagram Building, that signal resolution of the modern skyscraper. These architectural works, regarded as pivotal objects of the modern movement in architecture, were internationally known, as were his ascetic personality and aphoristic communications; together they amounted to a recognizable aesthetic. Before his death Mies, with a cohort of associates that included his grandson Dirk Lohan, was overseeing the work of his incorporated firm, the Office of Mies van der Rohe, work that included the final stages of construction for the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin and more preliminary stages of several other projects. It is one of these latter projects that competed with the authorial persona of its architect for the central role in architectural events in London, in the later twentieth century.

In 1958, the property developer Peter Palumbo (who would become churchwarden at St. Stephen Walbrook and who is now Baron Palumbo of Walbrook) set out to purchase plots of land in the City of London, at the heart of the financial center of the metropolis in the blocks near Mansion House and the Royal Exchange. Four years later, in 1962, he commissioned Mies to design for the prospective site an office tower facing onto an open plaza, set above an underground shopping arcade. Over the next several years, and with one visit to London to see the site in person, Mies and his Chicago office developed a scheme—known as the Mansion House Square scheme—for the tower and plaza that Palumbo presented to the City of London planning authorities in 1968. (Figures 51 and 52) This consultation with the authorities was required for several reasons, including the atypical height of the building—at two hundred eight feet, it would be one of a handful of towers in the City—as well as the significant alteration of existing street and traffic configurations by its footprint and by the large plaza. The required consultation was also due to the historical nature of the site itself; Mies’s prospective tower was surrounded by the work of other well-known architectural authors—George Dance the Elder’s Mansion House and Sir Edwin Lutyens’s Midland Bank would form two sides of the proposed plaza—and a number of less-regarded though still-authored Victorian buildings would have to be demolished to clear space for the tower. The City of London, an entity coextensive with yet autonomous from the larger metropolis, and governed by the historic Corporation of the City, possessed wide discretion in the management and regulation of development within its boundaries and would need to be persuaded. City authorities did view the proposal favorably, but because Palumbo owned only some of the hundreds of leaseholds that made up the scope of the properties to be demolished, permission was withheld with an instruction that he first attain sufficient control over the relevant properties to ensure that the project was unlikely to be forestalled. Over the next fourteen years, Palumbo followed this instruction, buying a dozen freeholds and hundreds of separate lease-holds. Meanwhile, Mies’s office refined the design, and a set of working drawings was prepared and ready for presentation in 1982, the year that Palumbo returned to the Common Council of the Corporation of the City of London with almost all of the required property under his control.

Figure 51. A photomontage of the Mansion House Square proposal shows the Mies van der Rohe tower flanked by George Dance the Elder’s Mansion House (at center-left) and Sir Edwin Lutyens’s Midland Bank (at center-right). Office of Mies van der Rohe (1981).

Figure 52. The proposed tower was first shown to the public in an exhibition held at the Royal Exchange in October 1968.

Figure 53. Photomontage of the Mansion House Square proposal in context, in a view along Queen Victoria Street, another of the streets opened by the metropolitan improvements of the nineteenth century. Office of Mies van der Rohe (1981).

By this time, now more than twenty years after Palumbo had conceived the project, a number of relevant circumstances had changed. Throughout the 1950s, the blocks of the City were filled with new construction to replace buildings damaged or destroyed by aerial bombardment during the war. Though many notable historic buildings had been spared—most famously, St. Paul’s Cathedral—vacant lots and half-fallen buildings were numerous. Damaged churches were most likely to be rebuilt, but the fabric of the City was replaced with newer and often speculative constructions. Through the 1970s, with the rapidity of postwar reconstruction evolving into the rapidity of the development of the finance economy, new towers appeared on the City skyline, and partially in consequence, a trend toward preservation had begun to emerge, so that the demolition of older buildings, even those of minor distinction, was now approached with greater hesitation. Conservation areas had been defined within the City, the first in 1971, several in the years that followed, and the year before Palumbo’s renewed application for planning permission a full review of the conservation areas had resulted in the extension or designation of almost two dozen such areas across the City.21 One of the conservation areas contained parts of the proposed Mansion House Square scheme, and a few of the affected existing buildings had been listed and therefore obtained various degrees of legal protection as either individual or grouped historic structures. (Figure 53)

These changes paralleled a more general revaluation of architectural style that had, over the preceding decades in Great Britain, catalyzed a concentrated hostility toward modernist architecture and fostered an increased veneration of English Victorian architecture (and historicist architecture more broadly). Summerson, among others, had contributed to this changed perspective, with his accounts of Victorian transformations of the metropolis. Although his was certainly an unsentimental view, it nevertheless offered an understanding of the seemingly unexceptional fabric of the city that illuminated the relation of architecture and historical context. In the view of Ouida and Morris, of course, the same buildings that Summerson carefully distinguished were an undifferentiated landscape of dullness that heightened the overall ugliness of London, and the commercialism that was the basis of the City’s existence was the commercialism that prevented the remedy of that ugliness. (see Figure 50) Ouida and Morris, in other words, might have given a sympathetic hearing to the Mansion House Square scheme, but the circumstances of historical perception had changed. By 1982, in contrast to 1968, Mies’s architecture was no longer presumptively contemporary, nor were the existing Victorian commercial buildings so readily designated as either insignificant or obsolescent.

Figure 54. The 1984 Mansion House Square inquiry in session in the Livery Hall of Guildhall. The room is arranged as a court proceeding, with the inspector at the head of the room, and the advocates and opponents at tables on either side.

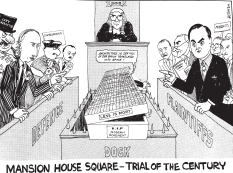

Palumbo’s renewed application faced strong criticism, and was summarily rejected by the Common Council. The autonomy of the City of London was not absolute. Its planning decisions could be subject to review by the government, and Palumbo therefore chose to appeal the decision, prompting a formal review of the case by an appointed inspector with authority to gather information and opinions and then to convey a recommendation to the secretary of state for the environment. To carry out the appeal process—and fully aware of the now considerable attention focused upon the Mansion House Square case by the media and professional groups—the inspector, Stephen Marks, convened a public inquiry held over ten weeks in 1984.22 This inquiry, while not an actual judicial proceeding, was nevertheless organized as one, with evidence presented by barristers and witnesses speaking in favor of or in opposition to the appeal through direct testimony and cross-examination. (Figure 54) (It was similar in format to, though much more public in nature and in interest, the hearing that would shortly follow for the faculty at St. Stephen Walbrook, which overlooked the Mansion House Square site.) In this forum, the persona of the architect came prominently into view, for of all the changed circumstances since 1968, perhaps the most consequential was the fact that Mies had died in 1969. Despite his death, the design was still attached to his persona, and in 1984 this attachment assumed a considerable importance in light of the markedly diminished appreciation for the proposed development on the part of planning authorities. (Figure 55)

In order to make their case, Palumbo and the project’s supporters— John Summerson for one, along with the architects Richard Rogers, Colin St. John Wilson, and James Stirling—placed Mies’s persona at the center of their argument, pointing to his stature as one of the most important architects of the twentieth century and to the widespread appreciation of his realized works as evidence of the value of this prospective tower. Summerson testified that the design was one of “irreproachable excellence,” and Rogers stated confidently that “Mies was remarkably consistent in his high standard: he hadn’t made a mistake yet and was unlikely to make a mistake here.”23 The advocates argued, in essence, that the City had an opportunity to construct a building by Mies, an architect of exceptional standing, and the price to be paid was a collection of Grade II listed buildings by “practitioners of a lower order of talent.”24 While proponents of the scheme affirmed its architectural value by reference to its architect, opponents—whose ranks, like those of the advocates, included architects and historians—sought to undermine precisely this argument, first by stating that the architect’s reputation was less a historical determination than a “myth [that] had nothing to do with the actual quality of his buildings.”25 “Mies had become a symbol,” they argued, which obscured the considerable inadequacies of his architecture. The theorist Geoffrey Broadbent asserted that “Mies really did not care at all about comfort, convenience, and the well-being of users … buildings by Mies suffered from over-heating, problems of vertical circulation, wind vortex and other problems.”26 Architect Terry Farrell described the proposed tower with adjectives that echoed those Summerson had used to describe the mediocre buildings of Victorian London: “repetitious, boring, and joyless.”27

Opponents sought to further undermine the attributed architectural value of the Mansion House Square scheme by suggesting that the design could not with certainty be attributed to Mies because the architect’s death forestalled his first-person testimony and because of the absence of indisputable alternate evidence of his hand in authoring the design. Where were the sketches or original drawings, asked John Harris, historian and founder of SAVE Britain’s Heritage, in a letter to the Financial Times: “Your correspondents make much of the tower having been designed and detailed both inside and out by the late master. To my simplistic mind this implies actual drawings by Mies, and not by assistants in his office. As not a single original drawing has ever been seen, neither at the Royal Exchange in 1968 nor at the RIBA this year, I am beginning to wonder if the claim is spurious.”28 Philip Johnson, critic and himself an architect, and Arthur Drexler, curator at the Museum of Modern Art, neither of them an enemy of Mies, submitted in written testimony that the proposed building was yet another weak derivation of Mies’s iconic Seagram Building, not an original contribution. The historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock, having been a leading authority in the rise of architectural modernism and therefore asked to give his opinion, also indicated that Mies’s involvement could have been only at a preliminary stage.29 In short, the opponents argued that the building was not definitively bound to the person of Mies in biographical terms, and therefore did not possess in aesthetic terms the superior value claimed by its advocates. Forced to rebut this line of argument, Palumbo’s barrister brought to the inquiry Peter Carter, who was the job architect on the Mansion House Square scheme, and who had continued the development of this and other projects in the firm after Mies’s death. Carter assured the inquiry that the building had been designed with the full involvement of the famous architect, whose typical working method left little in the way of sketches or original drawings. He testified that “Mies personally had initiated and authorised virtually every feature of the proposals, and had been involved till 2 weeks before his death; this scheme had been particularly dear to him.”30 Any subsequent changes were minor, he said, and had no effect upon the appearance of the design.

Figure 55. In Louis Hellman’s cartoon, Mies van der Rohe occupies the coffin at center. On the plaintiff’s side, Peter Palumbo is wearing the dark suit, and to his right is John Summerson. On the defense side, the man wearing pinstripes is Marcus Binney of SAVE Britain’s Heritage. Louis Hellman, “Mansion House Square—Trial of the Century” (1984).

Much of the contention of the Mansion House Square inquiry was pursued under categories, such as conservation or urban experience, that connected questions of aesthetics to various political or ethical stances toward cultural issues such as heritage or commercialism. Aesthetics alone would not be sufficient grounds for judgment. Style entered into the debate, in the form of a high modernism versus a high Victorianism or a rising historicism, but it pivoted upon the articulations of taste, for the various parties to the inquiry seemed to feel obligated to assign aesthetic evaluations accompanied by declared valuations. So, for example, the Mies tower might be beautiful in its form but also dull in its repetition. The Victorian streetscape might be vulgar in its appearance but elegant in its endurance. There’s no need for a suspenseful account of the outcome: following the inquiry and due consideration of the evidence, Inspector Marks recommended that Palumbo’s appeal be dismissed. Patrick Jenkin, the secretary of state for the environment, agreed, and on May 22, 1985, the Mansion House Square scheme joined the catalogue of unbuilt work.31 But what was curious in the inquiry’s engagement with the aesthetic register, and with the articulations of taste, was the pertinence of nuanced designations of authorship, both in their positive and negative manifestations, so that aesthetic argument might be shaped by classifications of architects variously as significant, or influential, or mediocre, shaped by the distinction of the authorial architect and the anonymous architect.

In 1982, before the appeal process commenced, the cartoonist Louis Hellman cleverly satirized the City Corporation’s refusal of the Mansion House Square scheme with a mocking account in which Christopher Wren and his 1666 plan for the rebuilding of London stood in for Mies and his Mansion House Square proposal. (Figure 56) In Hellman’s cartoon, Secretary of State Michael Heseltine was made into King Charles II, and Peter Palumbo was the equally alliterative Christopher Columbo. By associating Wren and Mies in this way, Hellman drew attention to the stature of the latter architect, and also to the conservatism of his opponents, but also indirectly and suggestively linked such political dimensions to an aesthetic register. For the parody depended upon a simple, comic transposition of appearance—Mies’s head (much photographed, with thinning hair combed flat) wearing Wren’s luxuriant wig. Though not consciously speculating on Mies’s authorship, Hellman’s cartoon, with its suggestive interchangeability, certainly foreshadowed the evidentiary debates that would follow as to whether the design was or was not by Mies. An architectural drawing—the evidence of Mies’s authorship demanded by John Harris and other opponents—has long been regarded as an extension of the architect’s mind, functioning as an expressive object whose attribution enables the recognition of the architect to occur at a remove from a physical building or an actual body. Such distancing mechanisms within design, which might also include the separation of the process of design from the process of construction, or the typically collaborative structure of specialization and techniques within architecture firms, are, despite the broad understanding that architecture firms are corporate bodies, more often than not veiled by personality. In 1984, the drawing had seemingly lost none of its standing to evidence agency, even as Peter Carter’s testimony brought to the inquiry an exacting description of the distancing figured not by the architectural drawing but by discussion, review, approval, and other habits and conventions of architectural practice.32

Sir Christopher Wren’s wig signaled much the same interpretation, with the additional clarity of presenting an explicitly aesthetic object—the wig, which manifests the vanities of fashion by suggesting a beauty to substitute for, if not an ugliness, then at least a bare reality—as the summary of all of these contested claims. The conclusiveness of the aesthetic was presented in the trial in more technical terms, perhaps, but the claim was more or less the same. Extensive explications of design details were agreed by both proponents and detractors to be salient elements. The claim that Mies’s buildings “spoke a single language” because they were unified by “7 shared characteristics” was submitted into argument, as was Ludwig Glaeser’s exhaustingly detailed explication of the variance in module, bay size, and ceiling height in Mies’s realized projects.33 Consisting of both repetition and difference, the aesthetic was established here as a conscious deliberation within the design indicative of the author it embodied. Inspector Marks appears to have understood that the importance of this proposition lay not in whether Mies’s authorship could be proven, but whether the case itself should rest upon authorial standing: “His authorship, whatever the degree of involvement, is a prima facie indication of the quality of the building, but it is ultimately not relevant to an estimate of the appropriateness of the building to the area; to give it great importance is to place undue emphasis on the building as a work of art.”34

Figure 56. Mies van der Rohe wears the wig of Sir Christopher Wren. Louis Hellman, “Ye Building News” (1982).

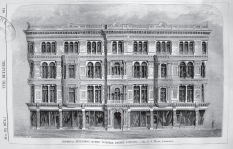

Against this emphasis was set another, the claim not for the aesthetic value of the individual existing buildings of the conservation area, though some were in fact listed, but for their aesthetic value as a group. The inspector concluded that “while it is obvious that considered individually they are not ‘the best of our heritage,’ I am satisfied that they possess special architectural interest and special historic interest.”35 This interest could not, though, be located in the function or historical use of the buildings. Nor could it be attested in terms of the professional accomplishment of their designers, only two of whom “could conceivably be considered principal architects of the period.”36 Instead, it was to be calculated in aesthetic quotients. But those were curious in themselves, with opponents of the demolition of the older buildings defending them with unconventional praise. The building at 23–38 Queen Victoria Street, for example, was “noteworthy for its sheer verve and vulgarity which give considerable interest, even if not a high quality of architecture.”37 Collected together, the buildings exemplified the scale, configuration, and experiential sensibility of the Victorian city; most notably, however, they exemplified its mediocrity and unmitigated ugliness. (Figure 57) These latter qualities were not disqualifications; to the contrary, they were the aesthetic value derived from a professional authorship distinct from the personified authorship of the Mansion House Square scheme.

Aesthetic Judgment and the Summons of History

The Mansion House Square inquiry was a venue for judgment of several kinds—social and economic, legal and administrative—but each of these was entangled with aesthetic judgment, which ran through the inquiry as justification, analysis, defense, and evidence. But to be employed in any of these terms in the inquiry, aesthetic judgment—whether of beauty or of ugliness in cognate terms such as vulgar, boring, and mediocre— required a means of substantiation. Rather than the historical recovery of prior paradigms of taste—Summerson’s “smiling surface of a lake whose depths are great, impenetrable and cold”—the process of the inquiry used the categories of professional authorship and personified authorship to attempt to ally the aesthetic and the historical. If the author was the initial category of personhood, then its counterpart was anonymity, both of them legible through a particular mode of aesthetic recognition: the signature. Though signature now inevitably invokes starchitects and their signature buildings, the architect as brand is only one narrow manifestation of signature, which is more usefully understood as the translation of personhood into a medium other than the actual person. In the case of Mansion House Square, one such translation would have been the legal attribution of liability, which, had the design been constructed, would be assigned not to Mies as an individual person, but to his incorporation as the Office of Mies van der Rohe or to the administrative licensure of the name stamped upon the working drawings; another, quite different, translation of signature that appeared during the inquiry was the assertion of the irreducible singularity of “genius,” or what the inspector termed the “prima facie indication of quality,” in which the designation Mies van der Rohe named a capacity beyond the grasp of biographical explanation. In such translations, the architectural person whose aesthetic production lay under scrutiny was not the living (or deceased) Mies van der Rohe, but another body acknowledged by the signature “Mies van der Rohe.”

Though the Mansion House Square inquiry convened in order to resolve a present concern and to make a determination of a future outcome, its debates and analyses were historical in nature; that is to say, the inquiry summoned the past to appear as witness and as evidence. The construction of signature played a crucial role in this summons. Understood as the translation of personhood into a medium other than the actual person, as a loosened attachment to personhood, signature can be seen to forge a contract with history that acknowledges a relation between a work and its creator at a specific moment, but that also extends that acknowledgment indefinitely forward into the future, even in the absence of an accompanying body. The architect, when encountered and addressed as a person through the technique of biography, has always appeared with an emphatic presentness, reenacting in the present any and all prior decisive moments as being unqualified and unchanged. This presentness is the repetition of an already determined intention that, although it occurred originally in the past, is placed again before its audience, unchanged, as fact. In this sense, personhood forges an isolation from context, with the completed fact reasserted without reciprocation to its newer historical moment, and in such a case one might lucidly and legibly reference taste and its standards as the means of aesthetic judgment. But when encountered as signature, the architect is addressed differently through a technique of inquiry that acknowledges distance; a signature moves forward in time, always newly aware of its changing context and offering a coherent and knowable persona (rather than a person) to any future appropriations, including a future tribunal.38

Figure 57. F. J. Ward, Imperial Buildings, Queen Victoria Street.

The Mansion House Square inquiry was in quite literal terms just such a tribunal, resummoning the signature to a venue of unexpected inclination, and even though the form of the inquiry was unknown and unanticipated at the moment the signature was produced, the signature could nevertheless be incorporated into the tribunal’s structure of thought.39 In other words, where the inquiry was forestalled in making its biographical address—because Mies was dead, no conclusion could be reached as to his actual involvement—it was freed by the inquisitional address of signature, able to examine and resolve anew the relation of architect, building, and present context. The inquiry was not thereby arriving at a conclusion as to whether or not Mies designed the Mansion House Square scheme; rather, it was producing an embodiment that enabled it to evaluate the scheme in both its prior and its present context. The testimony heard by the inquiry did not establish points of certainty; to the contrary, it produced an area of uncertainty, in which signature was an embodiment of a process of architectural practice; not a personification of Mies, that is, but an embodiment of the acts and operations of Mies’s office and its client. Put another way, the signature stood not only for individuality, already recognized by history, but also for anonymity, fully within yet unrecognized by history.

Through its corporate body, anonymity rewrites the contract with history, further loosening—though not severing—the conjunction of work and persona so that any future tribunal can no longer resummon the author to the same standard of presence.40 When the signature reads “Anonymous,” no specific body can be entered under judgment, no determined past is announced, and therefore no lineage can be established from the persona and to the work. A past exists nevertheless, manifest in the existence of the work, in its embodiment of decisions made and situational potentials realized. But this past cannot be described by the tribunal; it must instead be posited, put forward as a claim that burdens more than satisfies judgment. Regarding the fabric of Victorian London, Summerson conceded that “not much is known, except their names, about the builders of these things or of their architects,” and it for this reason that he endeavored to construct a broadly social motive, a collective orientation toward profit and domestic ease.41 The evidentiary appropriation of signature in such instances would be unable to claim the usual signifying parameters of personhood, and the anonymous signature would then predicate a different shape and agenda of inquisition of an architectural practice by a future tribunal—whether of historians or lawyers—with the relation of signatory to what has been signed premised upon a void, a distance, or a displacement. In a literal sense a depersonalization, the anonymous signature consists of a transfer between attributes of personality and personhood and those of institution, system, or technique. The corporate body assumes or indeed refuses responsibility for an aesthetic judgment of ugliness in a different manner than the authorial body, such that the anonymous signature actually solicits the projection of the tribunal’s own motives and the intentionality of its own aesthetic judgments.

In performing the actions of such of tribunal, using the instrument of signature to resummon the architect for the purposes of examination and inquisition, the Mansion House Square inquiry was the site of two significant consequences. First, by bridging the event of Mies van der Rohe’s death and installing the signature of Mies van der Rohe as the object of scrutiny, the inquiry embedded that signature with the predispositions of the inquiry itself; the signature became less a representation of Mies than a representation of the terms of interrogation to which the aesthetic was subject in the historical time and the legal space of the inquiry. The aesthetic register became a plane of deliberation for the adjudication of both property and propriety. Second, by bringing forward on equal terms the claims of the existing Victorian architecture on the site, the inquiry introduced a categorical opening for ugliness arising from the anonymous, mediocre, or professional objects of architecture, distinct from authored work. One of the curiosities of the inquiry testimony was the need for some of the witnesses who wished to protect the existing buildings and prevent the Mies tower to adopt an unfamiliar distribution of aesthetic judgment, valuing the ugliness of the former and devaluing the beauty of the latter. Not all witnesses did so—several emphasized the ugliness of the tower—but one outcome of the inquiry as a whole was to forge an identification between ugliness and the anonymous or the mediocre, and by so doing enabling ugliness to enter into debate as a diffuse or generalized condition, rather than only as a specific objective trait. The anonymous, professional fabric of Victorian London so disdained by Morris and Ouida was judged to have a signature of its own—and it is worth noting that a signature is, of course, the crucial instrument of that most basic of professional tools, the contract—that might be balanced against that of a better-known deceased architect.

The inspector’s recommendation and the secretary’s decision to deny the appeal brought an end to the Mansion House Square scheme, though not to the architectural event. Following the denial of his appeal, Palumbo conceded that “the Mies scheme is dead” yet did not abandon his plans to develop the Mansion House site.42 He commissioned a new proposal from the architect Sir James Stirling (who had testified in favor of the Mies design) and steered it through heated debate, refusal of planning permission from the City Corporation, and yet another public inquiry held in 1988; this inquiry, which resulted in approval for the scheme granted by the secretary of state, was appealed first to the High Court, then the Court of Appeals, and finally to the House of Lords, where the final judgment was rendered in Palumbo’s favor. This new building, to be known as No. 1 Poultry, was eventually completed in 1998. By then, Stirling had been dead for six years.43 (Figure 58)

The entanglements of authorship—individual and corporate, as signature and as anonymity—only increased with this seeming resolution of the Mansion House episode. The footprint of the new building was much smaller (and no longer accompanied by an adjacent plaza) and the scope of demolitions therefore considerably smaller, but the proposal still required the removal of one building, the 1870 Mappin & Webb building, which became the central focus of preservation efforts. The legal inquiry convened to evaluate the No. 1 Poultry proposal subjected Stirling’s design, like its predecessor, to detailed scrutiny and critique. The new design, characterized by Stirling’s highly articulated postmodern historicism, faced aesthetic disparagement that, if anything, exceeded that directed toward Mies’s tower proposal. In this case, however, the architect was present to answer the summons of the tribunal— Stirling presented evidence to two public inquiries, answering questions about his design and its revisions. But the seemingly incontrovertible affirmation of the person of the architect—the affirmation of a living and present author—did not endure for long. Construction of No.1 Poultry did not begin until two years after Stirling’s death in 1992, and the building’s posthumous attachment to a persona rather than a person thus followed a course similar to that of its predecessor project.

Figure 58. Photomontage showing the proposed building for No. 1 Poultry, viewed along Queen Victoria Street. James Stirling Michael Wilford & Associates (1986).

The Architect’s Two Bodies

The fact of the building’s realization has led more recently to an additional exhumation of the question of authorship. In 2015, the submission to planning authorities of a proposal to modify certain aspects of No. 1 Poultry met with a strong reaction. The firm Buckley Gray Yeoman had prepared plans for interior and exterior alterations to the building in order to redevelop its commercial spaces, prompting a number of previous participants in the Mansion House process, as well as some new protagonists, to speak out in protest. One preservation advocacy group called for the building to be listed Grade II (an appeal whose ironic relation to earlier events could not be overlooked) in order to prevent or mitigate any future changes to Stirling’s design. Palumbo and Rogers both endorsed this petition, with Rogers arguing that “James Stirling was the first British architect to develop a truly modern style” and that No. 1 Poultry, “one of his last buildings,” was a “beautifully designed, post-modern masterpiece.”44 Stirling’s widow, Mary Stirling, conceded the possible need for changes to the building to ensure its maintenance and viability, and what she called the building’s “integrity,” but opposed the specific proposals under consideration, which would, she argued, “emasculate the design concept.”45

Contrasting aesthetic judgments were accompanied by the disputation over interpretations of authorial presence. Some nineteen former employees of the firm Stirling, Wilford, and Associates (which had been a limited company, in other words, a corporate body) joined the defense of No. 1 Poultry, adding their support to the petition to have the building listed. Other parties, however, entered into the public debate to suggest that there was in fact a measurable distance between Stirling’s architectural ideas and the realized building. One of the titular partners of Buckley Gray Yeoman suggested that the new scheme intended only to rectify certain shortcomings that Stirling himself would have corrected had he been alive during the final stages of design and during the period of construction. The insinuation that the design was at some remove from Stirling’s intentions was translated into explicit terms by Tom Muirhead (who had worked with Stirling on the Venice Biennale bookshop pavilion), who stated flatly that if Stirling had been alive, the building that emerged from the construction site “would be profoundly different” from the one recommended for listing: “When I look at No. 1 Poultry I see the well-meaning approximation or simulacrum of a James Stirling building completed by acolytes, who must admit that they could not possibly have known what he might have done.”46 This claim provoked in turn a rebuke from Michael Wilford:

I worked alongside James Stirling for over 30 years (in partnership for 21 years) and participated in the meticulous design process which the office employed for each project. Ideas and decisions were sequentially layered over each other, obviating the need for subsequent changes and avoiding the occurrence of doubt and dissatisfaction with the design. Drawings and models were not released from the office unless James Stirling was satisfied with them. From a first-hand position I can confirm that the assertions are untrue, misrepresent the status of the project at the time and are self-serving.47

Echoing Peter Carter’s inquiry testimony from three decades earlier, Wilford’s argument returned to the difficult circumstances of architectural personhood and authorial presence, then as now balanced on a fragile calibration of persona, signature, and anonymity. The process employed by the office, and the sequential layering that Wilford claimed it produced, became embodiments for authorial presence, one subsequently verified by the support of anonymous (in terms of the process of design, though named at least as signatures on a petition) employees.

To affirm or refute the accuracy of either account of the design history of No. 1 Poultry, though, is not the point; rather it is to reveal the instrumentality of that uncertainty, which has origins in the aesthetic and in architectural ugliness. As with the usefulness of the pile at South Bank or the approbation of ambiguity and therefore ultimately incongruity in the case of St. Stephen Walbrook, instrumental terms were needed here to navigate that uncertainty, and the composite of corporate and individual personhood—the architect’s two bodies—answered that need. The building was awarded Grade II listed status in late 2016, but the events that preceded the result were once again a resummoning, a summons issued to the persona of the architect on behalf of a historical present. In the endeavor to assign responsibility as a prerequisite of passing judgment, this summons would again participate in the invention of the persona being recalled, translating the qualities and intentions revealed in an aesthetic register into those of a professional or corporate or bureaucratic register of categories, licenses, nomenclature, and other instruments of administration.

Figure 59. Memorial to Sir James Stirling, designed by Celia Scott and carved by Lois Anderson. Christ Church Spitalfields (2004).

Set against these impersonal and legalistic instruments is a small memorial plaque in the vestibule of Christ Church Spitalfields, in the east of London. Carved in slight relief, its details are spare, simply the form of an arch set above the outline of a pediment. (Figure 59) The plaque is dedicated to Sir James Stirling, whose ashes are interred behind the stone. Both the persona and the bodily remains are thus present here, in a building that is itself one of the masterful works of the architect Nicholas Hawksmoor, who designed the church at the beginning of the eighteenth century and to whose authorship is assigned the value of the architecture. Damaged in the nineteenth century and fallen into disrepair in the twentieth, the church was closed for a number of years before a program of restoration commenced. The fabric of the church was rebuilt and several hundred bodies exhumed from its vaults, with the object of bringing the building back to pastoral use while also preserving Hawksmoor’s architectural conception into the future. This dual intention, of an active church and a passive historical object, was set into tension by the persona of the architect.

Like the stone altar in St. Stephen Walbrook, the Stirling memorial required a faculty, for it contravened standards for memorials placed within churches such as Christ Church Spitalfields. First, it was not intended that the church become the repository of any more human remains; and second, a memorial, even without remains but certainly with them, was presumed to acknowledge a deep and specific connection to the church, both in terms of the practice of faith and also in terms of marked support for a particular parish. Stirling did not appear to have met these criteria, and thus more careful consideration by the Consistory Court was required. Opponents argued that the physical presence of human remains—the body of the architect, even as ashes—could pose a cultural boundary within the neighborhood of the church.48 But an even greater issue to the opponents was that Stirling had not been a parishioner, nor had he been a faithful member of the Anglican congregation, and to grant him the privilege of a memorial would open a precedent for any number of future requests for similar honors. The diocesan advisory council, in considering and approving in principle the Stirling memorial, had qualified that “it would not be appropriate for this great building to become a ‘pantheon’ for deceased architects.”49 The response to the objection that Stirling could not be considered a member of the church was that he had been one of the most dedicated advocates of the restoration of Hawksmoor’s building, and that upon his death donations to the church funds in lieu of flowers had provided enough money to restore the Georgian doors and entrance connecting the vestibule and church. As a benefactor in this sense and as a champion of Hawksmoor, he was seen as a legitimate candidate for the honor of a memorial.

The Consistory Court, although sympathetic to some of the opponents’ concerns, agreed with the petitioners that the memorial should be allowed, though as a singular instance and not a precedent for further concessions, and therefore granted the faculty. The presence of Sir James Stirling in Christ Church Spitalfields is therefore also attributable to developing and mutable ideas of architectural persona. In this instance, and in the Mansion House Square inquiry that preceded it, aesthetic judgment gave substance to instrumental discriminations through the institutional constructions of personhood, rather than through the descriptive devices of taste and style. Quite simply, the architectural profession was not just a fact, but a mode and a framework for aesthetic judgment. The conjunction of Stirling and Hawksmoor in this presumably permanent, not to say eternal, fashion puts forward the figure of authorship and persona as an instrument of social consequence, but at the same time the accompanying legal provisos that aim to make this memorial a singular instance give presence to anonymous bodies as well—to the exhumed bodies of the Christ Church crypt, but also to the dead and living bodies that structure the practice of architecture as a profession.