Chapter 7

The Monarch

In what was perhaps the most widely quoted accusation of architectural ugliness in the latter decades of the twentieth century, the Prince of Wales offered a scathing assessment of a proposed extension to the National Gallery in London: “Instead of designing an extension to the elegant facade of the National Gallery which complements it and continues the concept of columns and domes, it looks as if we may be presented with a kind of vast municipal fire station … what is proposed is like a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend.”1 The design of a long-anticipated addition to William Wilkins’s 1838 building had proceeded through a somewhat convoluted competition process.2 During the short list stage, in May 1982, the general public were invited to vote for their most and least favorite schemes among seven selected from the large pool of entries. Some eleven thousand out of nearly eighty thousand visitors did so, with the results defining a ranking of three proposals but also anomalous indicators of opinion, such as the fact that one design (by Richard Rogers Partnership) received enough most favorite votes to be in the top three while simultaneously getting the highest overall number of least favorite votes. The process proceeded clumsily, with Ahrends, Burton, and Koralek, the first choice in the public survey, selected as the winning firm but asked to propose a revised design, which was submitted for planning permission in December 1983.3 (Figure 60) Because of the prominence of the new extension, and the prominence of the listed building to which it was juxtaposed, the secretary of state moved the application directly into a public inquiry.

This inquiry, held in April 1984 in the Council Chamber of Westminster Council House, was not in itself a dramatic affair—the planning inspector noted that “a striking feature of the inquiry was the lack of involvement and attendance”—but it would be wrong to mistake this for unimportance or irrelevance.4 Rather it should be considered in terms of its sequestration of aesthetic discourse within procedural terms and categories. These terms and categories did not place such an emphatic focus upon persona as those in the Mansion House inquiry (which was to begin the following month), but they nevertheless placed the aesthetic dimensions of architecture into a procedural framework. And through this framework it was possible to subordinate the characterizations of taste in favor of those of propriety. The first design entered by Ahrends, Burton, and Koralek in the initial stage of competition had, like many other entries, attempted a deferential relationship to the original National Gallery building. Offset from the main building by an exterior rotunda, its primary facade of stone and glass conveyed the impression of four arched bays similar in scale to the neoclassical arrangement of the predecessor building, but more subdued in expression. In the firm’s final proposal, under examination in the inquiry, the masonry and glass of the facade were arranged into a dense grid of square panels and a thirty-meter-high glazed tower occupied the space between old and new buildings, with a stepped form and a scaffold of masts at its top. (Figure 61) Strong criticisms of the design included satirical insults by members of the Westminster City Council that the “intrinsically dull” design was an example of “lavatorial architecture”; in its place, one councilor wanted “something more beautiful, more lovely.”5 A defense of the scheme from the president of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) was less an endorsement of its appearance than a rebuke of the elevation of subjective opinions to the standard of technical analysis. At the conclusion of the inquiry, the inspector explicitly stated that he would not vouch for the aesthetic excellence of the design, but he recommended that planning permission should be granted. However, after receiving the inspector’s recommendation in June, the secretary of state (Patrick Jenkin, as in the Mansion House Square inquiry, responsible for the final decision) refused planning permission.

Figure 60. Notice of application for planning permission for an extension to the National Gallery, filed in December 1983 under requirements of the Town and Country Planning Act.

Between April and June, a pivotal and now infamous event occurred outside of the proceedings of the official inquiry. The Prince of Wales, addressing the RIBA—addressing directly therefore the architecture profession—delivered his scornful critique of the appearance of the proposed addition as “a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend.”6 The criteria for this judgment of ugliness were evident, consisting in the contrast of materials—although the proposed addition was masonry in part, glazing covered much of its facades as well as the tower—the contrast of ornamentation, and, most significantly, the contrast of a modernist building with the neoclassicism of the original. The prince’s statement immediately sparked controversy, recorded not only in newspaper articles and letters to the editor but also in confidential memoranda circulated in the Department of Environment, led by the secretary of state who would be responsible for a final determination following the inspector’s inquiry. The civil servants who wrote these notes expressed alarm at the “dangers of the Prince’s expressing his views on schemes which were sub judice.”7 The prince’s private secretary had contacted the department the day before the speech and explained that it would criticize the National Gallery proposal along with other projects (including No. 1 Poultry, also under inquiry). The reply from the department was that the proposal was under a planning inquiry and no official statement could be made, with the clear implication that the prince’s remarks were likely to be seen as improper.

Figure 61. Revised proposal for the National Gallery Extension, seen at center of the drawing, to the left of the “face of a much-loved and elegant friend,” Wilkins’s 1838 facade. Ahrends Burton & Koralek (1983).

After the speech, with the secretary of state facing criticism himself for not preventing the remarks, John Delafons, a veteran civil servant and deputy secretary of the department, concluded, “I would agree that HRH [His Royal Highness] was very unwise to launch such an attack on two schemes that are currently the subject of planning inquires. Both schemes are financed by private developers and Parliament has provided the means, under the Planning Acts, for dealing with such proposals.” Recommending an official course in response to the event, he advised, “As HRH did not put his point of view at the public inquiry on either scheme, neither the Inspectors nor the Secretary of State are obliged to take any account of it in reaching their conclusions. . . . We should, for the purposes of the formal procedures, treat it as we would had the remarks been made by any other person. . . . The fact that the remarks were made by HRH does not mean that they should be treated any differently as regards the inquiry procedures.”8 The prince’s statement did not enter into the inquiry as testimony, or indeed in any formal way as evidence, but the exchange of worried memos and the public commentary in the press made perfectly clear that the statement was not treated as that of any other person. When the secretary of state decided, as he had full discretion to do, to reject the planning inspector’s recommendation and to refuse planning permission it was immediately and not unreasonably supposed that the prince’s speech had encouraged his decision. The influence of this particular statement was simply not comparable to that of other published criticisms, such as those from the Westminster councilors, carrying as it did the authority of a future monarch and resembling therefore nothing so much as the wish of a patron. Yet the statement was treated not only as an assertion of royal prerogative, because it was also understood to be in alignment with a broadly popular feeling of disaffection for modern architecture and therefore to be, quite potently, an assertion of public preference as well.

A few years later, in 1987, at the annual dinner of the Planning Committee of the Corporation of the City of London, the Prince of Wales voiced his serious concern over Paternoster Square, a planned development adjacent to St. Paul’s Cathedral: “Surely here, if anywhere, was the time and place to sacrifice some profit, if need be, for generosity of vision, for elegance, for dignity; for buildings which would raise our spirits and our faith in commercial enterprise, and prove that capitalism can have a human face.”9 But the designs that had been proposed seemed to him to be entirely given over to financial calculation, excessive in their square footage, deficient in the generosity of their public amenity, and in style and scale antagonistic to the historic monument that they would overshadow rather than complement. Such designs, he argued, could not plausibly be praised as good unless they were being assessed only according to some astringent quantitative measure or some impassive technocratic checklist. Referring to free-market economics, to the influential writings of Hayek and Mises, to the deregulatory Big Bang of London’s financial markets, he made clear his understanding of the neoliberal frameworks that encompassed these schemes and deplored their reductiveness. He hoped that they would be reconsidered in favor of more contextually sensitive—and if necessary financially sacrificing—designs.

In making this argument, Prince Charles presented himself as a barometer of public opinion expressing feelings that were widespread and commonly held: “it is not just me who is complaining—countless people are appalled by what has happened to their capital city”; “if there is one message I would like to deliver this evening, in no uncertain terms, it is that large numbers of us in this country are fed up with being talked down to and dictated to by an existing planning, architectural, and development establishment”; “we, poor mortals, are forced to live in the shadows of their [the professionals’] achievements.”10 This “we” was not a royal “we.” The pronoun nominated a collective of the British public whose sentiment and desires could be identified and conveyed. An eyebrow must be raised, of course, at any future monarch’s claim to speak as a poor mortal, with, and therefore on behalf of, the common man. Yet the sentiment expressed could have had resonance at any moment from the middle of the nineteenth century onward. The anticipation of some more elevated social condition marked by the qualities of elegance or generosity had a Ruskinian echo, while the optimism that commerce and capitalism might be aimed toward benevolence repeats the hopeful cadences of postwar economic booms. There was also the regretful conviction that economic logic and aesthetic consequence are at odds, and that the increase of the one requires the sacrifice of the other, a common enough refrain, as was, above all, the complaint about a professional class hostile to the desires of a general public.

Following his rhetorical inquiry as to whether profit might be sacrificed for elegance, Prince Charles posed the crucial question: “what place, if any, do the opinions of the general public have within the legal labyrinth of the planning system?”11 The current system, he told his audience, had relegated public opinion secondary to professional opinion, such that a system of technocratic projection and assessment operated in largely self-reflexive terms, disengaged from pedestrian concerns, popular taste, and, at its most extreme, even from commonly held human values. This critique that “what architects think” must be utterly dissimilar from “what people think” is familiar enough, having proliferated throughout Europe and North America (and thence beyond) during the latter half of the twentieth century. Spoken in London in 1987, amid shifting perspectives on the social and cultural inheritances of the welfare state—with modern architecture very much one of these inheritances, as evidenced by the inventory of London County Council buildings constructed around midcentury—and amid the production of new configurations of aesthetic discourse, the sentiment expressed not a regretful retrospective view, but a call for architects and the developers who commissioned them to begin to take notice of the demands of popular opinion. More generally, though, it was a critique of the bureaucratic architecture of the postwar period, the managerial practices of the welfare state, and a critique of the relation between architecture and the welfare state. The presumption here was that a form of governance in which the articulation of decisions and procedures (such as what to build, or how, or what a building should look like) was the responsibility of bodies at a remove from representative government and at a remove from personal influence had resulted in an abstracted realm of technical vision.

Such critiques depended upon the idea of public opinion, a phrase and a conceptual term very much taken for granted as attention played, and continues to play, rapidly across architectural, economic, or political merits in an architectural debate. Taken for granted not in the sense that public opinion is ignored or falsely interpreted, but in the sense that public opinion has been presumed to exist, to be a concrete and measurable expression within the structures and protocols of cultural debates and civic proceedings. Put simply, public opinion is presumed to be a fact. From the 1930s through the 1950s, Mass Observation famously aimed to produce comprehensive records of the thoughts, feelings, and habits of Britons that could be deployed first as a form of academic or cultural knowledge and later commercially as market research; the extensive archive of letters and diaries compiled by Mass Observation give credence to the perception that public opinion is a factual matter, but they also demonstrate that its factuality must depend upon the circumstance or the institutional setting in which it can be instrumentally deployed.12 In other words, public opinion must have a medium; judgments of ugliness must have a medium. The means by which public opinion and professional opinion meet and contest one another do not remain stable, though curiously stable has been the agreed point of contention, or the pivot of difference, around which they orient themselves: the aesthetic.

Architecture and the Bodies of Public Opinion

In the succinct assessment of the architectural historian Peter Collins, “ ‘Aesthetics’ have long enjoyed undeserved prominence in definitions of architectural ideals.”13 Collins made this claim within an argument that identified the misaligned perceptions of public and profession as a specific and rather critical problem. What Collins described as the “credibility gap between professional comprehension and public comprehension” was increasing, he argued, because both sides mistakenly prioritized the aesthetic dimension of architecture. He did not wish to deny that aesthetics were a fundamental concern, but questioned their primacy in judgments of value. The aesthetic dimensions of architecture should instead be incorporated into a matrix of considerations embedded in the design process—structural efficiency, human safety, material longevity— fully known to professionals but invisible to the public. It becomes clear that Collins sought to achieve some stabilization of judgment, at a moment at the beginning of the senescence of the welfare state and with the first suggestions of a postmodern condition emerging, and that he sought this stabilization on terms favorable to the professional, arguing that the success or failure of an architectural design was “only determinable by those with the professional skill to understand [the full matrix of considerations].” An unhelpful conclusion if Collins had not taken one further step, which was to admit the fragility of this professional judgment: “I would contend that the real problem of professional ideals has nothing to do with rival aesthetic theories of the plastic arts, but is the result of a dilemma which confronts all those who practise [sic] a profession with full awareness of their human frailty. That dilemma is the extent to which any professional expert can really trust his own judgment.”14

Recognizing this fragility of professional certainty as a dilemma led Collins to argue against both the certification of absolutist ideals and the consensual diffusion of architectural ideals into a “climate of opinion,” to argue against both technocratic dogmas and popular taste cultures. In their place Collins advocated an assertion of architectural principles based upon judgment that was continually tested and refashioned in a process similar to that of legal reasoning. The inspector who led the Mansion House inquiry expressed a similar view, noting at the very outset of his “Findings of Fact” that “it is always difficult to know what weight to attach to expressions of public opinion, especially where, as in relation to the present appeal applications, there has been no controlled testing.”15 More relevant here than the aesthetic or interpretive principles Collins himself might actually have endorsed is the mediating process of judgment enacted by the inspector, for it describes a process capable of containing professional and public opinion, a process of testing and revising judgment in light of conditioning facts on the model of legal procedure.16 The incremental development of the administrative state that emerged in Great Britain in the mid-twentieth century included the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act, which established a comprehensive planning permissions process under which virtually all new development—all new architecture, in other words—was subject to review by local planning authorities. This same act also incorporated provisions regarding the treatment of listed historic buildings, provisions that came to operate quite directly with the planning permission process. Under the 1947 act, architecture became subject to formal public scrutiny. An application for planning permission would be reviewed by a planning board, whose members might be professional but who were delegates of the general public, according to a transparent protocol that also allowed for interested parties to submit their views or opinions. If permission was refused, the 1947 act provided the possibility of an appeal, and it is this particular contingency—the appeal—that evolved into a singularly instrumental space of architectural debates on civic aesthetics.17

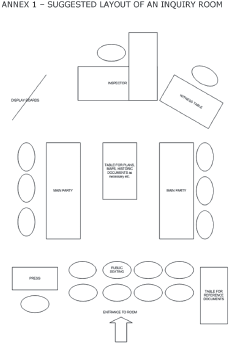

The appeal is made by the party applying for permission to build who has been denied, and it is made to the secretary of state.18 The secretary of state then designates a planning inspector to hear the appeal, and the inspector in turn convenes a public inquiry, a hearing of material arguments for and against the proposed development. It is also possible for the secretary of state to “call in” an application for an inquiry, even prior to the local planning review; this action is customarily taken in cases where the public interest regarding an application is manifestly a national concern or appears to turn upon a conflict in national policy. The inquiry adopts the model of a judicial proceeding, with the inspector in the role of judge (though he or she is not in actuality a judge in the legal system), and with advocates for and opponents against the application for planning permission. These advocates and opponents, very often represented by lawyers, present evidence; expert witnesses are called and examined and cross-examined; interested institutional parties may weigh in with their positions on the case. Even the room in which an inquiry is held is modeled on a courtroom. (Figure 62)

The inquiry permits the expression of embodied points of view, though these expressions are mediated through the protocol of the inquiry itself and the institutions that stand in for individuals in this civil arena. To whom do the points of view belong, and by whom are they embodied? The property owner is one, and, as evidenced by the history of nuisance law, holds a preeminent standing derived from the ancient respect accorded to property in common law as a basic unit of social organization. The property owner (who may well be a corporate body) is embodied by a legal representative, a solicitor or not infrequently a barrister. Alongside the property owner, embodied by the same legal representative, is almost certainly a member of the architectural profession, the architect (again likely a corporate body) responsible for the proposed design under scrutiny. On the other side of the adversarial courtroom is the public. This public has many actors, and can include neighboring property owners or local government and local institutions or members of the local community. In planning inquiries related to prominent projects such as the National Gallery extension or the Mansion House Square proposal, the embodiment of the public will often include the presence of one or more national amenity societies.

The national amenity societies are voluntary groups whose efforts are directed toward the preservation of significant works of architecture, and that have been recognized by acts of parliament to have legal standing within planning inquiries. The oldest of the societies, the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, was founded in 1877 by William Morris, and given legal standing in inquiries in 1968 under amendments to the Town and Country Planning Act. Three other societies represent specific historical periods: the Georgian Group, founded in 1937 to advocate the preservation of architecture from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries; the Victorian Society, founded in 1958 to pursue the protection of buildings built during the reign of Queen Victoria; and the Twentieth Century Society, founded in 1979 as the Thirties Society but since renamed to represent an expanded interest in British architecture from 1914 onward.19 These four national amenity societies thus comprehensively cover the span of British architectural history, not as governmental agencies, but as voluntary embodiments of public interest. In the circumstances of a given inquiry, the national amenity societies will gather expert witnesses, provide documentation, and assemble briefs and petitions, all as elements to constitute a concrete expression of public opinion.

Figure 62. “Suggested Layout of an Inquiry Room,” from The Venue and Facilities for Public Inquiries and Hearings (UK Planning Inspectorate, 2013).

The monarch has no special legal standing or royal prerogative within the space of the planning inquiry. The planning inquiry as constituted in 1947 was intended precisely to diminish such forms of prerogative, and did so in formal terms. As a representative of public opinion, the monarch could appear in the space of the inquiry through one of the elements that possess legal standing, such as one of the national amenity societies. It is also possible that the Crown may be represented in the inquiry as property owner; the Duchy of Cornwall, for example, in the possession of the Prince of Wales, amounts to 130,000 acres of land. But there is no formal standing or privilege as an embodiment of state authority, and the planning inquiry is thus marked by a particular absence, the absence of a prerogative capable of claiming a peculiar dual authority of singularity (a monarch) and multiplicity (a body politic).20 If the inquiry is made resistant to the blandishments of that voice, it is also resistant to the endorsement of that voice, so that patronage would properly have no role in the legal procedure. The “fact” of aesthetic approbation can be entered into the deliberations of the planning inquiry in various ways—for example, through expert testimony by architects, or by architectural critics, or borough councilors, as they were in the case of the National Gallery inquiry. But the case of the National Gallery extension, with the result of the inquiry weighed equally, as it seemed, with the statements made by the Prince of Wales, exposed the possible translation of aesthetic judgment into the register of patronage, with the dual voice of the monarch and the people assuming a peculiar standing as being removed from the legal inquiry, yet still enforceable upon it.

For the architects who formulated the principles of civic architecture in Britain in the early modern period, the relationship between the monarch, architecture, and public life was an explicit concern. (Figure 63) For Inigo Jones and his contemporaries, in the decades prior to the Civil War, and for Sir Christopher Wren and his contemporaries, in the decades following the Restoration, the distinction between the monarch and the people was politically fraught as diverse elements of civic life sought authority within the structures of common law, or the court, or political economy. But within this context, the role of architecture was one of representational clarity: to represent the monarch, and therefore the state, was to represent the people or the nation. Under the medieval conception of the king’s two bodies, the monarch was understood to have a physical, mortal body but also a metaphysical, immortal body, the one installing a real presence, the other conveying a symbolic duration. For Inigo Jones, as surveyor of the king’s works responsible for the design of royal buildings such as the Banqueting Hall, the two bodies of King James I had direct architectural corollary in the columns of his all’antica designs. These columns were present in the building as physical structure and as metaphysical appearance of idealized proportions.21 The relationship between lived reality and legal authority was contained in singular form by the idea of the king’s two bodies, and contained therefore, in the aesthetic register, in the architectural column as well.

Figure 63. Tapestry portraying Queen Elizabeth I received by Sir Thomas Gresham on the opening of the Royal Exchange, 1571. Richard Beavis, “Opening of the Royal Exchange” (1887).

For the architects who developed the civic landscape of Britain following the Second World War, the conceptual and political understanding of the relationship between the monarch, architecture, and public life was obviously very different. (Figures 64 and 65) For Sir Basil Spence or Sir Denys Lasdun or their contemporaries, the monarch who attended the opening of a civic building or who presided at a ceremonial laying of a cornerstone stood at a distance from public life not because of a divine right to assert law but because of the deliberate separation of the monarch from governance instituted over the intervening centuries. When Queen Elizabeth II, in 1956, set the foundation stone of Spence’s new Coventry Cathedral, its modern architecture was taken to be a symbol of a newly restored public life, but with no parallel restoration of the monarch to legal authority. Whether there will, retrospectively, be identified a Neo-Elizabethan period of architecture to reflect the long-reigned modern monarch in similar fashion to her predecessors remains a subject of speculation. But with or without a stylistic designation, what is perhaps distinct about the period is the measurable reflection in architectural terms of a peculiar relation between monarch and public that is at once more distant and more intimate. It is not the designation of style that will reveal this, but the translations of taste into procedural forms through aesthetic debate over the matter of ugliness. Like the column for Jones or Wren, these procedural forms mediate the embodiment and disembodiments of the monarch; they mediate a corporeal presence and what was in the early modern period a legislative presence, but which is now an instrumental legislative absence, instrumental because by being absent from the legislative forum, it is able to lay claim to the form of public expression.

Figure 64. Queen Elizabeth II in the foyer of the National Theatre at its official opening, October 25, 1976.

Figure 65. Queen Elizabeth II lays the foundation stone of Coventry Cathedral, March 23, 1956.

Of course, the royal figure who has with his public expressions entered strongly into architectural debates and who has repeatedly put forward the charge of ugliness is not the monarch but a monarch-in-waiting, the Prince of Wales, heir to the throne. Prince Charles’s standing within these public debates, and specifically within the legal proceedings that accompany and shape them, is far less definite and therefore far more complex. The public has standing, through the mechanisms outlined above, but the monarch does not, as a result of the historical arc of representative democracy from the Restoration to the present day. Prince Charles, however, though he is neither public nor monarch, would suggest the representation of both public and monarch. And it is precisely this status that, through the aesthetic debate on ugliness, has been brought vividly into view as an aspect of the civil sphere, for following the refusal of planning permission for the first proposed extension to the National Gallery, and continuing as Prince Charles’s critical pronouncements upon architectural projects accumulated, concern arose over the propriety of his interventions into public debate. If the planning process had been established precisely in order to ensure representation in the matter of the development of the nation’s built environment, did these interventions circumvent that process entirely, permitting the entrance of a royal fiat presumed extinct? Supporters of the prince and his architectural opinions argued that they did not, that they amounted to no more than expressions to which any private citizen was entitled. Critics of the prince and his architectural opinions argued that they usurped an extra-constitutional power to which the prince was not entitled, and amounted to a direct and unconstitutional intervention by the monarchy into the political life of the nation. While newspaper reports often characterized the events as squabbles over taste, fought between a professional class and a princely man of the people, the judgment of ugliness was here not solely a question of aesthetic preference, but an assertion of political authority between these rivals.

In the Shadow of Sir Christopher Wren

The postmodern historicism that in the 1980s and 1990s brought forward a neoclassical architectural movement (called the New Classicism by some of its protagonists) accompanied by broader antimodernist sensibilities centered architectural debate at the millennial turn around questions of style: traditional versus modern and therefore traditionalists versus modernists. But although style was undoubtedly a significant aspect of the conceptual transformations then taking place, it was in many ways more symptom than cause. From the 1980s onward, the architects, critics, politicians, and patrons pitted against one another in forum after forum established alignments between the overt characteristics of architectural appearance and the presumed social standing, economic standing, and even ethical standing of supporters and detractors of those appearances. And it was therefore often the case that existing motives—the political predispositions of individuals or their economic interest—were presumed to be the spur toward aesthetic preferences.22 In a manner recalling eighteenth-century aesthetic philosophy, taste and morality were once again identified, though now with the complex layerings of modernity rendering them institutional characteristics as much as personal ones. The politics woven through architectural disputes such as the National Gallery extension, the Mansion House proposal, or the hearing on St. Stephen Walbrook, though evident in many of the personalities involved, could be equated with aesthetic judgments only in complicated ways. While the individual motives of Lord Peter Palumbo, or the Prince of Wales, or those of architects such as the modernist Lord Richard Rogers or the classicist Quinlan Terry are obviously pertinent, to see them as conclusive is to remain constrained by an older paradigm of taste. In the present-day iterations of the long British debate on architectural ugliness, the alignment of political orientation and aesthetic preference in a simple accounting of political interests may distract from the critical perception of the instrumental structures and processes that have emerged to enable aesthetic judgment to participate in civic life.

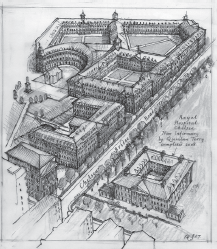

In late spring 2005, the design for a new infirmary at the Royal Hospital at Chelsea was reviewed by the local authority, the borough of Kensington and Chelsea planning committee, and put forward for a vote. But just hours before the committee was give its approval, the deputy prime minister, John Prescott, invoked Article 14, a three-week holding delay to consider, as his office announced, whether possible objections to the scheme required the proposal to be called in for a planning inquiry. Two government bodies, English Heritage and the Council for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE), had already given their clear approval to the scheme, which was to neighbor the original hospital buildings designed by Sir Christopher Wren. One local group, the Chelsea Society, founded in the early twentieth century in response to demolitions to protect the character and amenities of the neighborhood, had expressed opposition to the scale of the new building, but the architect of the scheme, Quinlan Terry, was well known for his contextualist approach to design and reverence for historical architecture such as the Wren buildings.23 It quickly emerged that the government had taken the unusual and unexpected decision to impose the holding delay in response to concerns that Richard Rogers had privately conveyed to the government along with a request that the proposal be called in for an official planning inquiry. The dispute then unfolded in the pages of professional journals and the daily newspapers, with Rogers and other critics disparaging Terry’s design as ill-conceived and inappropriate company for Wren, and Terry and his supporters protesting the unorthodox intervention into the planning process. To Rogers’s scornful description of the proposed infirmary as a pastiche, an “architectural plagiarism” unsuited to the site, Terry responded angrily that the intervention was an abuse of unofficial access to the government.24 At the end of the three-week period, the government chose not to convene a planning inquiry, allowing the scheme to proceed under the local permission. Terry’s new infirmary opened a few years later. (Figure 66)

Significant as it was, in retrospect this episode was in some ways only a prelude to another dispute centered upon Wren’s Royal Hospital at Chelsea. This subsequent dispute concerned the development of Chelsea Barracks, a parcel of land adjacent to the Royal Hospital Chelsea (and facing Terry’s infirmary building across the street) sold off by the government to a private consortium. The joint developers—CPC Group of the London property magnates the Candy brothers, and Qatari Diar, a real estate investment company of the Qatar Investment Authority controlled by the emirate of Qatar—had proposed a large complex of residences, with a density calculated for financial return, and commissioned Rogers’s firm, Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, for the architectural design. A first scheme, in a modernist idiom contrasting with Terry’s adjacent classicism, with rectangular blocks set perpendicular to the streets and clad in glazing and panels set between clearly expressed structural frames, was modified in response to comments from CABE and from the local council. In 2009, the revised scheme, still with its idiom of structural frame and panels, still with separate blocks, and still with modernist conviction, had progressed to the point of submission for planning permission. But shortly before the case was to be formally reviewed, the developer withdrew the planning application entirely, with the intention to hire a new architect to pursue the development. In this instance of a sudden suspension of the planning proceedings, it emerged that the Prince of Wales had conveyed privately an opinion on the design, explaining directly to the emirate his feeling that the proposed scheme and its architect were unsuitable.

Figure 66. Aerial view of Royal Hospital Chelsea, with the original Wren buildings at center and the new infirmary designed by Quinlan Terry at the top center of the photograph.

The antagonism between Prince Charles and Lord Rogers was by this point decades old and firmly entrenched, but the provocation in this particular case, from Prince Charles’s point of view, was not that the proposed design was by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, but that Wren’s hospital grounds should not have a context of modern architecture imposed upon them by this adjacent development; from Rogers’s perspective, the provocation was not simply the criticism of the design, but more egregiously the manner in which that criticism had been conveyed outside of the protocols of the planning process. Rogers immediately accused the Prince of Wales of an unconstitutional intervention in the democratic process established more than a half century earlier by the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act. By conveying his opinion in private—effectively speaking as one royal to another—Prince Charles had conveyed the impression, according to Rogers, of an official disapproval that the emirate would necessarily take into account. The prince’s disapprobation, however, had no official legal standing; it had not been entered into the by then well-advanced planning permission process, as had many statements of public support and opposition. The defense offered on behalf of the Prince of Wales was twofold: first, that his communication was that of a private citizen and was therefore not an intervention into the planning process, and additionally, his aesthetic judgment was correct and shared by others—Quinlan Terry, with a sketch drawn by Francis Terry (his son and partner), quickly published a substitute design for the development, giving an explicit model to accompany the prince’s judgment. (Figure 67)

Figure 67. Proposal for Chelsea Barracks, drawn by Francis Terry. Quinlan & Francis Terry Architects (2009).

The aesthetic prompt for the ensuing controversy—the architecture of the proposed development, its suitability in relation to its famously authored architectural neighbor, and its public appreciation as a contemporary form and idiom—these elements that were claimed to have ignited the dispute were soon translated into a political register. The prince had, Rogers and his supported argued, circumvented the constitutional separation of the monarchy from political process, creating not only an unfair distortion of the evaluation of the Chelsea Barracks scheme and a consequent financial loss, but also a constitutional crisis about the role of the monarchy itself. While representatives of the prince declined any comment as to whether he had issued private communications regarding Chelsea Barracks, the details of his actions were subsequently confirmed.25 He first had written to the prime minister of Qatar, cousin to the emir, saying, “I can only urge you to reconsider the plans for the Chelsea site before it is too late. Many would be eternally grateful to Your Excellency if Qatari Diar Real Estate Investment could bequeath a unique and enduring legacy to London.”26 Two months later, he took the opportunity of a private meeting with the emir in London to repeat his disapproval of the proposed design. The application for planning permission was withdrawn soon thereafter.

A number of leading architects, an international group with Pritzker Prize winners and other honorees among them, joined Rogers in denouncing the political implications of the prince’s actions and expressing alarm over the implied assumption of power:

It is essential in a modern democracy that private comments and behind-the-scenes lobbying by the prince should not be used to skew the course of an open and democratic planning process. . . . If the prince wants to comment on the design of this, or any other project, we urge him to do so through the established planning consultation process. Rather than use his privileged position to intervene in one of the most significant residential projects likely to be built in London in the next five years, he should engage in an open and transparent debate.27

Other participants in the architecture and planning professions pointed out that the ideal of a transparent planning process accessible equally by all British citizens remained just that, an ideal, and that the prince’s actions, while undesirable, were not unique. The president of the Royal Institute of British Architects offered the diplomatic explanation that “it’s difficult for citizens, even the Prince of Wales, a prominent Westminster resident, to take part in the planning process. Most people feel disenfranchised, and believe that decisions about big developments such as Chelsea are ‘done deals’ taken behind closed doors,” while the editor of Building Design, Amanda Baillieu, suggested, as the prince himself had previously done, that he was “speaking up because he feels local people, aside from anyone else, are not being listened to.”28 To Rogers and others, however, these actions amounted to nothing short of an “abuse of power” requiring an urgent response: “We should examine the ethics of this situation. Someone who is unelected, will not debate but will use the power bestowed by his birth-right must be questioned.”29

The challenge issued by Rogers and those who agreed with his complaint took on a broader significance beginning the following year, when a journalist for the Guardian newspaper filed an appeal to fulfill a freedom of information request to see copies of letters that Prince Charles had written to government ministers. These letters, which were known as black spider memos for their distinctive scrawl in black ink, raised the concern that the prince had communicated his opinion on a range of issues with political implications, and had therefore violated the constitutionally established political neutrality of the monarch. Though the Guardian request sought memoranda written a few years prior to 2009, the publicity around the Chelsea Barracks dispute only strengthened the demands that these communications should be made public; indeed, the dispute was specifically referenced by the applicants. A complicated legal process ensued, beginning first with the refusal by the information commissioner and government departments to fulfill the request, followed by a judicial hearing held in 2012 before the Upper Tribunal of the cases made by the two parties, the newspaper on one side and government departments and the Prince of Wales on the other. The argument hinged upon two concepts, the public interest and the constitutional status of the heir to the throne, that appeared to be set into conflict by the prince’s communications, with the presumption of the public benefit of transparency set against the constraints imposed upon the relation between the monarchy and the government. It is an acknowledged constitutional premise, known as the tripartite convention, that the monarch has “the right to be consulted, the right to encourage, and the right to warn” and that these rights legitimate communications with ministers in government.30 However, the Prince of Wales is not the monarch; he is the heir to the throne, and the heir to the throne does not have any constitutional role.

But another constitutional convention, known as the education convention or the apprenticeship convention, does pertain to his participation in political life, specifying the need for the heir to the throne to be educated over time in his future monarchical responsibilities by rehearsal of them.31 Such preparation for kingship may include the performance of ceremonial tasks as well as discussions with members of government in order to become cognizant of relevant issues, debates, or policies. Barristers presenting the case against the release of the black spider memos put forward the education convention as a central point of their brief, arguing that such rehearsals are customarily and necessarily private and do not constitute an advocacy or persuasion toward specific political outcomes. In putting forward this claim, they depended upon an assertion that the education convention had become more expansive—or even that a new convention had been established—as a result of Prince Charles’s long-standing efforts to engage in public discourse and his many contacts with public officials on his topics of concern.32 Justifying this “novel” and “innovative” privilege would require a difficult parsing of the public and private roles of the prince, because his established habit of speaking publicly, even, as in his remarks on Paternoster Square, as a poor mortal, as one of the public himself, could not be reconciled with the constitutional requirement that the monarch not offer public views on matters of public interest. It could not be argued that his communications fell under the convention of rehearsal for kingship if his actions were otherwise in stark contrast to the constitutional requirements of that future kingship. Additionally, if the claim were that his communications fell under the prerogative of the tripartite convention, an even more serious question arose as to his possible arrogation of a constitutional privilege that belonged to the monarch alone.

The Upper Tribunal was not persuaded by the novel constitutionalism suggested to protect the black spider memos. Although the tribunal did not find his petitions to government ministers to be unconstitutional (as the Guardian journalist asserted in the filing, and as Richard Rogers argued in the Chelsea Barracks dispute), they regarded them as being outside the boundaries of constitutional convention. On the additional point of monarchical privilege, the tribunal spoke unambiguously: “It is the constitutional role of the monarch, not the heir to the throne, to encourage or warn government. Accordingly it is fundamental that advocacy by Prince Charles cannot have constitutional status. . . . It would be inconsistent with the tripartite convention to afford constitutional status to the communication by Prince Charles, rather than the Queen.”33 Considering the appeal from the opposing side and the weight to be placed upon public interest, the tribunal found that the presumption by the Prince of Wales, and by government ministers, that the communications were private had no bearing—believing them to be confidential did not make them so. “Those who seek to influence government policy must understand that the public has a legitimate interest in knowing what they have been doing and what government has been doing in response, and thus being in a position to hold government to account. That public interest is, in our view, a very strong one.”34 Before the black spider memos could be released, however, the attorney general vetoed the tribunal’s decision, arguing in part that the letters contained “most deeply held personal views and beliefs” of the Prince of Wales, and that these should be protected in order to preserve the perception of his political neutrality.35 A sequence of challenges and appeals over the next two years to overturn the veto eventually culminated in a hearing at the Supreme Court, which ruled that the attorney general’s veto had been improperly applied and authorized the release of the black spider memos.

Published in May 2015, the black spider memos did not in themselves satisfy the public curiosity that had been provoked by the strenuous effort to keep them private.36 Prince Charles had written to the prime minister and other government figures about subjects ranging from agricultural regulations to homeopathy to the conservation of explorers’ huts in Antarctica, in each case with a quite specific point of attention, but collectively the memos contained no significant differences from his public stances. Yet as the drawn-out appeal demonstrated, the argument lay not in the topics but in the very fact of his advocacy and motivated communication to ministers, a process that muddled the formal as well as the informal categories of civic discourse. At the same time as he pursued his private conversations with members of the government, the Prince of Wales presented arguments to professional audiences in the voice of public opinion, suggesting a formulation that is not the familiar distinct segregation of public and private realms, nor a private sentiment expressed aloud in public, but rather the possible construction of a public opinion privately expressed. The Prince of Wales may or may not continue with this mode of communication—a 2010 amendment to the freedom of information laws has exempted the heir to the throne, and the second in succession to throne, along with the monarch—but the instances of architectural judgment of ugliness, in regard to the National Gallery and to Chelsea Barracks, revealed a newly provocative dimension of civic aesthetics: that rather than representing the king’s two bodies in a direct, but archaic manner, architecture may serve to dissemble the body politic of the public.

Juridico-Aesthetic Transactions

The personal realm of taste, in order to enter into public discourse and to assume any instrumental effect over civic aesthetics, requires a sequence of translations or structures of mediation—but even then it may not be correct to imagine that taste is the origin or source of judgment. The formulation and development of discursive instruments such as the legal perspective on libel and criticism or the organization of professions has led to the possibility that those instruments too have a role in the production of judgment, which may then be directed back into the standards of taste. The inquiry, as a central forum (and again, instrument) in the processes of planning, should thus be understood not as a neutral space, nor as a space co-opted in advance by protocols of power, but as an apparatus that sustains a field of transactions of judgment. The legal inquiry is a modern apparatus, installed as one of the constitutive elements of postwar planning and more generally of the welfare state structure itself, but could reasonably now be regarded not as a legacy of modernity—an artifact of the welfare state—but as a constitutive space of postmodernity, having evolved over time not only in itself, in its capacities, but also and perhaps more eventfully in its relations to the other dimensions and structures of the state and civil society. The ecclesiastical inquiry, the venue of the debate over the altar at St. Stephen Walbrook, having eluded the consolidations of postwar modernity, also possesses a constitutive function in postmodernity, only in a different form than its civil parallel. With legitimacy not externally guaranteed by the state, the postmodernity of the apparatus of legal inquiry now manifests in its heightened susceptibility to contingency, a susceptibility apparent most dramatically in its contrast to the presumptive stability of a legal structure. The law should be resistant to change—and so it is in its outward forms—but it is how those forms now produce translations among the contingencies surrounding them that reveals the manner of architecture’s participation in judgment and in civic aesthetics.

Through his involvement in the episode of the National Gallery extension, the proposal for No. 1 Poultry, the planning of Paternoster Square, and the abandoned version of the Chelsea Barracks, the Prince of Wales, as person and as legal entity, vividly exposed the contingency of what is designated as public opinion. Theorist Jean-François Lyotard coined the term différend to designate a dispute that cannot be resolved determinately and equitably because the means of judgment is itself under dispute.37 When the parties in the dispute do not share the same rule of judgment, then resolution is necessarily forestalled. This is not the same as saying nothing will happen—a decision will be issued, in the planning inquiry by the planning inspector—but this decision will emerge after the performance of incompatible rules of judgment. The différend is not extinguished; it continues to exist, but embodied as a set of provisional translations between aesthetic and other registers. In telling instances in London in the 1980s and 1990s, in disputes over ugliness, such translations accompanied the appearance of architecture in the legal space of postmodernity. As a generality, Lyotard’s différend is a space of the postmodern condition, of “incredulity toward metanarratives,” a space of fragments and ungrounded authority.38 But more specifically it is a space inhabited by what Lyotard called phrases and genres, with phrases being the multiple and incommensurable depictions in language of events, experiences, motives, or perceptions, and genres being the protocols through which those phrases are assembled and oriented toward a particular end. No stability or determinacy is guaranteed by this orientation, for genres also are multiple and coexistent within the différend.

Although the planning inquiry was conceived in the rationalist administrative framework of the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act as a space of clarity and the resolution of judgment, the inquiry cannot fulfill that task with consistency. And in the events recounted above, it has come to perform instead the function of the différend. The différend, though, is not a failure in the conventional sense, rather it performs a function of deferral, of decision without resolution, that enables the emergence and propagation of the aesthetic—or the juridico-aesthetic, or civic aesthetics—as a register of postmodernity. In the legal inquiries recounted in the episodes of this book, such inquiries now appear to be inducing the modulation of phrases and genres in debates about the built environment of postmodernity. As public opinion circulates through these venues, it is not merely validated or refuted; it is material in the assembly of legal aesthetics. Genres such as “public opinion”—for public opinion is indeed a genre—have to be contrived, fashioned to permit the transmission of certain phrases, phrases that have to be modified in their turn in anticipation of the genres they will encounter. To claim to speak in the voice of the public, to announce public opinion, is not enough to enter into the juridico-aesthetic transaction of the inquiry in a defined role and with recognized standing. As Inspector Marks made clear, public opinion must be subject to further tests to achieve its recognition in the space of inquiry and to be deemed evidentiary proof of aesthetic judgment. The assumed prerogative of the Prince of Wales was one such test, in which an older conception of the monarch’s two bodies found its echo in a constitutional chimera.

Figure 68. Cracked windows and weathered facade of the abandoned Broome and Butler Houses, two towers that stood at the Chelsea Barracks site. The buildings, designed by Tripe & Wakeham, opened in 1962 and were demolished in 2014 for the redevelopment of the site.

As for Chelsea Barracks, the development is proceeding ahead, with different architects and a different architecture, committed to neither a modernist nor a classicist dogma. In the shadow of a building John Wood must have visited, and in a prosaic repetition of Wood’s transformative program of civic improvements, the cracked windows and weathered facades of existing buildings on the site will be replaced by new materials and new architectural arrangements. (Figure 68) Aesthetic judgment will be cast, certainly, but with the instruments foreshadowed by Wood’s experiments toward a civic aesthetics—the social instruments of assessment and their means of expression in the legal and social embodiments of architect, profession, and monarch. As the architectural affairs at Chelsea Barracks have been set in order, the legal repercussions of the dispute have subsided also. The CPC Group filed suit against their partners, Qatari Diar, arguing that they had an obligation to make reasonable efforts to obtain planning permission for the proposed development, and by withdrawing before the hearing they had breached their contract.39 Mr. Justice Vos ruled in favor of CPC Group, freeing them to seek damages, but also sympathized that Qatari Diar had been put in a difficult political position by the prince’s comments. This suit was ultimately settled between the two parties, and CPC and their preferred architect Lord Rogers would soon have their attention consumed with another speculative project, the luxury residences of One Hyde Park, on the former site of Bowater House (the same building Ian Nairn had nominated as an aspirational average for contemporary architecture). In this project, too, difficulties of public opinion would arise, with aesthetic criticism of the design accompanied by moral disapprobation, but none that rose to legal challenges. Legal concerns played out at a further distance from public view, as advisors grew concerned over the need for CPC Group to maintain its legal standing as an offshore company. The details lead into the abstract territories and arcana of globalized finance, sovereign funds, and the vast circulations of capital characteristic of contemporary London. But the precipitating judgment of ugliness still resonates, as it did in the London of two centuries earlier when John Soane projected his precinct of private taste into the public realm, and was met with the denunciation of his palpable eyesore and the inconvenience of a legal inquiry.