Chapter 3

TO BE BLACK AND FEMALE

By the 1850s, when they stepped out into public Black women were accustomed to being read. Observers—finding them at the market or in a carriage, tending a garden or soothing a child, traversing a park or entering church on Sunday—sized up women. Edmund Burke, whose words Frederick Douglass reprinted in his newspaper, expressed a gentler version of such encounters: “To describe her body describes her mind; one is the transcript of the other.” Burke found in his ideal woman (likely his Irish Catholic wife) a harmony that Black women, too, aimed to embody. Too often, they were taken for one quality or another, as a woman or as an African American. Their task was to develop self-awareness and then put to words what it meant to live at an incongruous crossroads. In solving this puzzle, Black women established a distinct and enduring touchstone for how their vision of rights might begin.

IN 1850, BLACK Americans looked out across the nation’s political landscape and saw that it had taken a troubled turn. Fissures opened everywhere, dividing the old movements and giving birth to the new. The geography of Black life expanded, with important settlements taking hold as far west as San Francisco and Sacramento in California. Black communities strained under the labor strife that arose in the many cities that welcomed immigrants from places like Ireland and Germany. Whiteness as a political identity had calcified, reinforcing how racism organized politics, the economy, and the social world.1

The abolitionist movement persisted, but only as an array of awkward allies. Those who worked by moral suasion persevered, but activists who viewed political advocacy as the most effective way forward operated in a rival antislavery society. Some abolitionists, particularly African Americans, embraced violence: direct and admittedly illegal resistance to slavery employed especially in the rescue of fugitives. William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass ended their long alliance, thus severing one of the movement’s most powerful partnerships. Their differences were, in part, ideological—with Garrison still committed to moral suasion and Douglass drawn to politics. When Douglass began publishing his own newspaper, the North Star, one that competed with Garrison’s Liberator, it signaled that Black abolitionists would be demanding increased control in a movement that spoke for their interests.2

By the early 1850s, the Black-led colored conventions had hit their stride. Black leaders regularly met in their home states and in national gatherings that provided an independent political platform for men excluded from state legislatures and national political parties. The delegates came out of local, grassroots organizations that conventions knit together. Print culture served as a powerful instrument for organizing. Those who missed meetings read newsweeklies like Frederick Douglass’s Paper (formerly known as the North Star) along with pamphlets that recorded proceedings and broadcast them to remote locales. Increasingly, the perspectives of enslaved people influenced Black politics. Fugitive slave narratives put firsthand testimony at the center of political deliberations. The genre reached its high point with the 1855 publication of Frederick Douglass’s second narrative and the stories of William Wells Brown, Solomon Northup, and Jermain Loguen. Sojourner Truth released her narrative in 1850, adding a distinct woman’s perspective to these tales about the journey from slavery to freedom.3

Activists recommitted to Black politics in response to the Compromise of 1850. Congress had passed a series of bills by which it hoped to settle tensions generated by slavery’s expansion west into new lands seized at the end of the Mexican-American War. The act permitted newly added territories to decide whether they would permit slavery. California was admitted as a Free State, and the domestic slave trade was banned in the District of Columbia. But it remained to be seen whether this—or, indeed, the Compromise itself—would calm the tension between pro- and antislavery factions. A final provision of the Compromise, a new and onerous Fugitive Slave Act, especially troubled Black Americans. It promised that slaveholders could demand the help of federal and state officials in capturing fugitive slaves. Those fleeing bondage were no longer entitled to due process protections, such as a jury trial or the right to testify, even if state law said otherwise. In the face of this national edict, thousands of Black Northerners fled farther north to Canada, seeking refuge on free soil. Those left behind exercised new vigilance and radicalism as they defended themselves and their communities.4

Those who left the United States after 1850 did not act merely on impulse. A new movement was gaining momentum, an unprecedented Black-led emigration movement. Its leaders encouraged African Americans to reconsider their place in the world. Perhaps they could make a better home in West Africa, Canada, or the Caribbean. It was time, emigrationists urged, to go after a chance for full citizenship in their own lifetimes. Opponents of emigration bitterly denounced such schemes and reiterated the fact that Black Americans had paid many times over for citizenship’s full privileges in the United States. Emigration opened yet another fissure within Black politics, one in which old allies faced off across a divide that went to the core of their political identities.5

Women also aimed to remake the decade’s politics. Beginning in 1850, they convened the first national women’s conventions and made plain that a new movement, a women’s movement, was part of the political landscape. It had originated in the antislavery meetings of the 1830s, and local gatherings such as those in Seneca Falls and Rochester, New York, in 1848. But the meetings of the 1850s were neither incidental to another cause, nor were they local or impromptu. Organizers intended to build and sustain the women’s conventions over many years. They wanted to attract broad attention. They wanted political rights. And they brought a broad array of concerns to the floor. The first meeting in 1850, at Worcester, Massachusetts, included demands for property rights, access to education and employment opportunities, and a general insistence upon women’s “political, legal, and social equality with man.” The convention even acknowledged enslaved women, whom the delegates deemed worthy of “natural and civil rights.”6

Everywhere across this fractured political landscape, Black women took advantage of the cracks. They were newly strategic and took every chance to make inroads. Rarely did African American conventions recognize their claims on politics—many still insisted that race and gender were separate concerns to be addressed by separate movements. But, in spite of the opposition, Black women found their voices standing at the podium or with pen in hand. They spoke with the same courage that had emboldened Maria Stewart two decades before. They surrounded themselves with like-minded women just as Jarena Lee found support in the Daughters of Conference. Stepping into the political spotlight, Black women preached, taught, and demanded to be heard on their own terms.

FOUNDING A NEWSPAPER might sound like little more than a gentle knock on the doors of power. Since the 1820s, Black editors, wielding bold pens, had exercised outsized influence on public opinion. Nineteenth-century journalism rested to an important degree upon the borrowing between papers, which emphasized an editor’s ability to curate his pages. Rather than producing a mash-up of thought, editors assembled a distinct point of view using their own writing, that of regular correspondents, and pieces borrowed from far-flung news outlets. This exhibited power of the first order. Black women aimed to seize it.

Mary Ann Shadd’s career as a journalist is a testament to her sense of herself as a person with rights. Born free, to parents Abraham and Harriet Shadd, she started out life in the slaveholding state of Delaware but was educated in Pennsylvania, where her family moved to avoid the Southern bans against educating children of color. She worked as a teacher and then, in 1853, migrated to the city of Windsor in Canada West, today’s Ontario. There, Shadd joined a growing community of Black Americans who had fled—or, in the language of the day, emigrated from—the United States in search of free soil. A deep despair underlay the decision to relocate; many migrants doubted that the United States would ever abolish slavery and then acknowledge them as full citizens. Shadd settled down in a new country and, with a little bit more freedom, soon emerged as one of the era’s most insightful commentators. She lived in exile, but Shadd’s heart and mind remained fixed on the past, present, and future of America’s former slaves, especially women.7

She had, from the beginning, been an upstart. In 1849, at twenty-six, Shadd wrote a long letter to Frederick Douglass, responding to his request for suggestions on how to improve the “wretched conditions” of free Black Americans in the North. Shadd did not couch her comments in a timid or deferential tone and, instead, she claimed authority based in her “ten years of teaching Black children in all Black schools.” But she was unwilling to let an editor impose his whims and put out her own twelve-page pamphlet, Hints to the Colored People of the North. It was an openly political tract published to “arouse her readers with a direct analysis of the condition of northern Blacks, regardless of whether it might offend.” Some men were admittedly uncomfortable. A supporter chided: “What think you of the language of this young sister… does she tell the truth or not! As one man I am sorry that I have to answer in the affirmative.” Perhaps her words contained “too much truth!” another observed. Martin Delany, a former slave, journalist, abolitionist, and emigration proponent, mixed praise for Shadd’s pamphlet with doubt about her character, branding her “a very intelligent young lady, and peculiarly eccentric.”8

Settling in Canada West meant starting over just beyond the shadows cast by eminent men like Douglass and Delany. How Shadd decided to publish a newspaper, it is difficult to say with certainty, but the idea must have been brewing for some time. Canada provided her just enough of an opening to realize her dream. Shadd built a team, one that included her future husband, barber Thomas Cary. Some men helped with the writing and editing, while others set type, rolled ink, and operated the printing press. She was a new publisher who, while the pages dried, traveled to promote the paper to subscribers across Canada and the United States. She was soon at the helm of a brand-new weekly, the Provincial Freeman. By publishing her own paper, Shadd joined the ranks of “first” women on the day the inaugural issue left the office. With the next issue due in just seven days, she did not have much time to boast.9

Instead, Shadd worried. The Provincial Freeman needed committed subscribers to stay afloat. She hoped to win readers with relevance, timeliness, and a voice that guided the lives and the political culture of Black people. This required, Shadd concluded, that she conceal the extent of her role at the Provincial Freeman—readers would be uncomfortable getting their news from a woman, she judged. She named two men, Samuel Ringgold Ward and Alexander McArthur, as editors and, masking her sex, instructed that letters to the paper be addressed to “M. A. Cary.” Later that first year, Shadd was “promoted” to the role of publishing agent, which acknowledged that she traveled the United States and Canada to win subscribers. Of course, it was Shadd who had promoted herself. Not until May 1856, two-plus years later, did she list herself as an editor and by her full name, along with coeditors Henry Ford Douglass and her brother Isaac Shadd. By November that year, she had married, and the Provincial Freeman’s masthead reflected the name change: Mary A. S. Cary was now listed as among the paper’s editors.10

Cary never spoke openly about the dilemmas she faced as an editor who was also a woman. Instead, she used her editor’s prerogative to tell readers about the difficulties that women like her confronted. The paper chronicled the history and labors of women’s rights leaders and explored married women’s legal rights, the content of women’s education, and avenues for women’s work. She celebrated women’s accomplishments, especially their firsts, and featured noted thinkers, such as Jane Swisshelm, who held forth on issues ranging from women’s mission to men’s sphere.11

Cary’s Provincial Freeman read like an open forum, but as editor, she always determined which opinions made it into print. The paper advocated that women had the right to speak and write in public, control property, hold elective office, obtain an education, and enter the professions. In contrast, other columns reminded women about the demands of respectability and domesticity, criticized women who refused chivalrous gestures, encouraged refined manners, and warned against petty jealousies. It was a primer on the uneven terrain that women like Cary navigated. The Freeman shined a special light on African American women’s achievements, from Cary’s own grueling lecture schedule to the orations of the “eloquent and talented” poet Frances Ellen Watkins and “the fine literary and artistic attainments” of educator and emigration activist Amelia Freeman.12

Women came forward and used the paper to explain their own journeys through racism and sexism. “Henrietta W.” responded to an article on education. Her letter begins with a cautious and apologetic tone: “I hope you will pardon the seeming boldness.… I have ventured to address you, with the view of ascertaining whether you will receive communications coming from one of my sex.… I have taken up my pen with a trembling hand and a fearful heart.” Henrietta confessed that she did not possess even a “common school education,” yet she offered her perspective, asserting that “the class of teachers under whom it has been our misfortune to be placed have been just a little better than none at all.”13

In return, Henrietta received a lesson or two. In her reply to Henrietta, Dolly Bangs first admitted her own fears: “I belong to ‘that class styled the weaker sex’ and… I can sympathize with her in her state of anxiety.” Bangs also offered reassurance: “A writer need never fear of bringing down anything like ridicule upon herself… the only danger would be in her extreme modesty.” A woman need not hesitate to join the debate on education, or any other issue, for such a move was “hers by right.” Bangs claimed for women rights equal to those of men: “Would it not be preposterous to ask of man that which he has not the power to give?—he like woman, is but a creature dependent upon his Creator for his own rights.” She argued that to discourage women from asserting public leadership “now, in the afternoon of the nineteenth century… seems ridiculous.” All her readers, she maintained, had an interest in encouraging women’s public endeavors. To do otherwise was to squander the “vast amount of latent talent which might be used.” Yet women themselves must be the guardians of their own fate: “It is her right, as her duty, to press boldly forward to her appointed task, otherwise who is guilty of burying her talent?”14

CARY SAW A bit of herself in Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, the poet and antislavery lecturer. Harper also had been born free in a slaveholding state, Maryland, and worked as a teacher before she entered politics. Both women had become teachers after receiving some of the best education that a young Black woman might expect. The two wrote poetry and prose, and shared interests: temperance and antislavery, though they differed on emigration. Cary published Harper’s early work in the Provincial Freeman: an essay titled “Christianity” and a poem, “Died of Starvation.” By 1856, while Harper was lecturing on the antislavery circuit, Cary published a lengthy missive out of Bath, Maine, that praised her in broad terms. Cary, the editor, drew upon the words of a correspondent, “Humanitarian,” who described Harper’s speeches as “fervent,” “eloquent,” and “with almost superhuman force and power over the spell bound audience.”15

By the winter of 1856, Cary was out to promote the work and the career of Harper. A reprint from the Anti-Slavery Standard noted the “talented young lady” had undertaken an ambitious schedule of lectures across Pennsylvania. It ended with an advertisement that encouraged those “desirous to have the services of Miss Watkins” to write to the abolitionist James Miller McKim in Philadelphia. It was part of Cary’s effort to promote Black women. Watkins was an instrument in her overall effort to crush racism. She frankly compared white women such as “Miss E. T. Greenfield [and] Mrs. Webb” to “Miss F. Watkins.” Watkins, “by competing successfully with the most celebrated white females, in their several professions, notwithstanding the superior advantage of white women, can be safely said to have removed from their class and sex the stigma of natural inferiority.” Cary signed the note with her initials, “M.A.S.C.,” claiming such thoughts as admittedly her own.16

AMONG THE WOMEN that Cary featured in the Provincial Freeman was Sojourner Truth. Cary reprinted a piece that quoted Truth as having gently mocked white Americans who mixed abolitionism with racism. Cary used Truth’s words to level a critique that was at the root of Black women’s political thought: in American politics, they set the bar high, such that commitment to a good cause did not excuse complicity with evil. The newspaper was likely the only place that Cary and Truth—two towering intellectuals and activists—ever met. And still, for Cary, the encounter was unforgettable.17

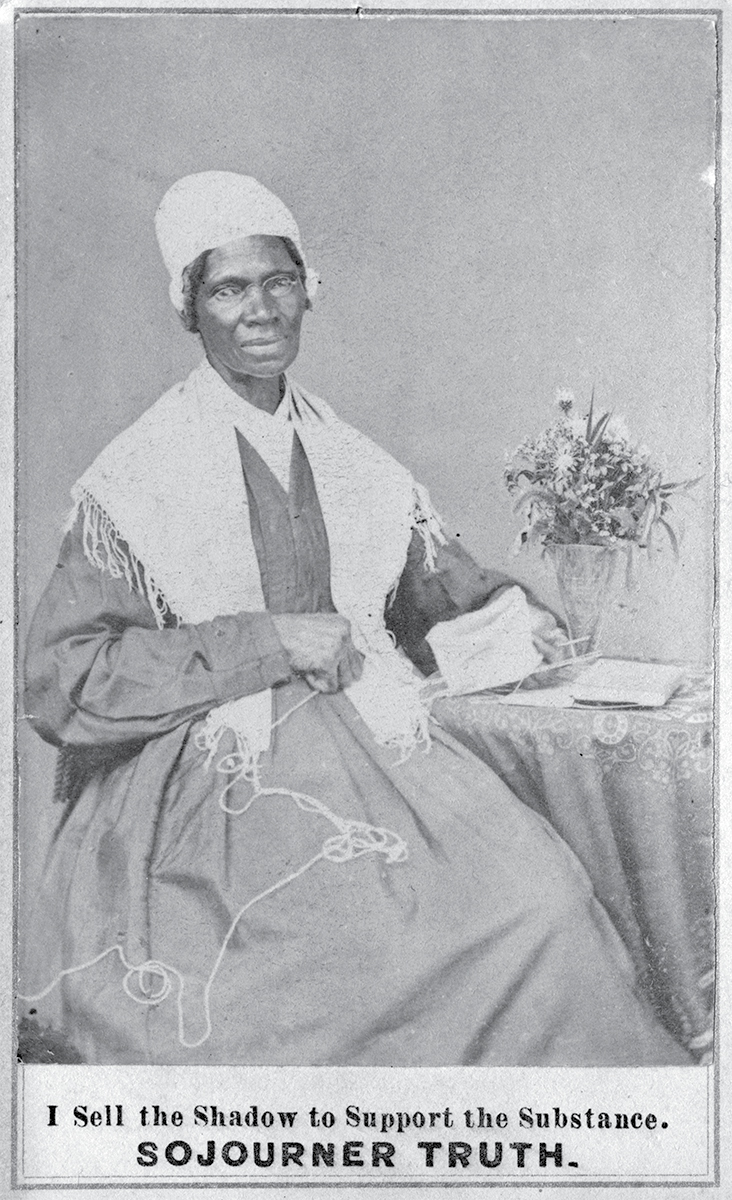

Sojourner Truth, “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance,” 1864

LIBRARY COMPANY OF PHILADELPHIA

Few who met Sojourner Truth forgot the experience. She was an imposing presence, standing six feet tall and speaking with a Dutch accent she had acquired during her early life in Upstate New York. Truth attracted audiences as a former slave and advocate for abolition and women’s equality, and she eventually commanded the podium with unrivaled frankness, humor, and personal testimony. She once told a story, for example, that included a struggle between her desire for freedom and the need to care for her children. She adorned herself in bonnets, shawls, and, later in life, dresses crafted from fine fabrics. Truth knew that audiences had questions about what kind of woman she was, and she became as deliberate as any woman of the 1850s about crafting her own image. Wasn’t she a woman?18

Truth’s early life had been unorthodox. Born enslaved, Truth had claimed her own freedom, endured separation from her children, spent years living in a utopian, free love community, and by the 1840s had finally settled in Northampton, Massachusetts, where she embraced antislavery activism. As she embarked on a political career, Truth hoped audiences would understand her point of view—and so she sat for a series of interviews with a white abolitionist, Olive Gilbert, to whom Truth dictated key episodes of her life story. The resulting Narrative of Sojourner Truth, published in 1850, became a peer to the era’s best-known slave narrative, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, a Slave. It also became Truth’s calling card, and she sold the pamphlet on the lecture circuit. But self-definition for a woman unable to read and write was not a straightforward task. Gilbert’s desire to show white Americans the wrongs of slavery did not mesh with Truth’s story about a Black woman’s hardships, losses, and the irreconcilable choices she faced when enslaved. The problem of being spoken for and about by others would haunt Truth’s entire public life.19

There was no precedent for the moments when Truth stepped to the podium at the women’s conventions of the 1850s. On the antislavery circuit, Truth had kept the hospitable company of white Americans who evidenced little prejudice. She counted among her friends British antislavery lecturer George Thompson and radical Quakers Isaac and Amy Post of Rochester, New York. Though she never held office, Truth appears to have avoided the ambivalences that had troubled Hester Lane in the American Anti-Slavery Society a decade earlier. These associations, along with her ties to figures like Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, buttressed Truth as she became the first Black woman to join the new national women’s movement.20

Truth was indeed a first when she arrived in Worcester, Massachusetts, in October 1850—Black women had not attended the women’s meetings of 1848 in Seneca Falls and Rochester, New York. She arrived, the sole delegate representing Northampton, Massachusetts, to face as large an audience as she had ever encountered. Over one thousand people filled Brinkley Hall to capacity, with others milling about outside after being turned away. In Worcester, women presided but shared leadership with men. And they dominated the podium. Others spoke about Truth long before it was her turn. Speakers expressed sympathy for the enslaved. They affirmed their commitments to the antislavery cause. One resolution strongly alluded to the distinct plight of enslaved women as targets of sexual assault: “The claim for woman of all her natural and civil rights, bids us remember the million and a half of slave women at the South, the most grossly wronged and foully outraged of all women.” In Worcester, Truth alone embodied that memory. She finally took her turn and delivered a speech full of biblical allegory that lightly touched upon women’s political rights.21

Ill-fitting for Truth was how speakers juxtaposed the condition of “women” against that of “the slave.” President Paulina Davis drew a parallel between “Woman” and “the contented slave” as two figures who had not yet claimed their rights. Abby Price lamented how, in “many countries,” women “were reduced to the condition of a slave” and decried how “the very being of a woman, like that of a slave, is absorbed in her master!” Price especially implored men: “Will you… dim the crown of [your sisters’ and wives’] womanhood, and make them slaves?” Elizabeth Cady Stanton did not attend the Worcester meeting, but her letter to the convention echoed the sentiments of Davis and Price, warning men “so long as your women are mere slaves, you may throw your colleges to the wind.” These deliberations left Truth alone to carve out her own space, as a woman who began life enslaved but who was now free, who stood alongside women in the North rather than enduring as a captive in the South. Truth was not a metaphor. She was alive, with presence, voice, and her own views about women’s equality.22

In the following year, as plans for a next women’s convention came together, organizers wondered whether including women like Truth posed a problem; Truth and others had introduced the issue of racism into meetings called to combat sexism. Pittsburgh-based journalist Jane Swisshelm objected to how, during the 1850 meeting, delegates had introduced “the color question,” what she deemed a sidebar and a distraction. “The convention was not called to discuss the rights of color; and we think it was altogether irrelevant and unwise to introduce the question.” To succeed, women should not take on the “additional weight” of problems that concerned Black men. And Swisshelm doubted that Black women would expect to make gains through a women’s movement: “As for colored women, all the interest they have in this reform is as women. All it can do for them is raise them to the level of men of their own class.”23

Swisshelm published her thoughts in her newspaper, the Saturday Visiter. But if Truth had gotten wind of the suggestion that she might undercut the women’s meeting, she did not take it to heart. In May 1851, she made her way to the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron and took a seat among the scores of delegates. As she listened to the proceedings, once again Truth heard speakers compare the slave to the woman, much like she had in Worcester. This time, however, Truth responded. Her words were nearly lost for all time—the members of the Publishing Committee left Truth’s words on an editing room floor when they published sixty pages of official proceedings.

But in the audience at Akron, journalists Marius and Emily Robinson made certain Truth’s speech survived. The two were long-time antislavery activists, teachers of African American children, lecturers on the antislavery circuit, and, by spring 1851, editor and publishing agent of the Salem, Ohio, Antislavery Bugle. Witnesses to the entirety of the women’s proceedings, the Robinsons published their own version of the deliberations, beginning with the keynote address delivered by Frances Dana Gage. When it came to Truth, the Robinsons aimed to do their best to convey her words and their force. They deemed her remarks “most unique and interesting” and admitted that it was difficult to capture the effect that Truth had had on the audience as a speaker who was Black, a woman, a former slave, and an exceptionally talented orator who mixed humor, colloquialism, and her own life experience to great effect.24

Truth had waited her turn in Akron, following women whose remarks showcased their high levels of education, status, and experience. She could not match such credentials. Still, during her years on the lecture circuit she had learned to riff off the remarks that preceded her own, and it paid off. Truth reframed the convention, resetting its goals as defined from the perspective of a Black woman. She began, “I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman’s rights.” There, as she was, unlettered and unrefined, Truth made the case that she was the truest embodiment of women’s rights. Slavery was no mere metaphor and the labor it demanded had made Truth the equal of any man: “I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man.” This experience was also the philosophical foundation for a women’s movement. She urged: “I have heard much about the sexes being equal; I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it.” Truth then spoke to the men in the room, turning to the Bible, the book that blamed women for humankind’s earthly woes, for a perspective on justice: “I have heard the Bible and have learned that Eve caused man to sin. Well if woman upset the world, do give her a chance to set it right side up again.”25

Truth never spoke the words most often attributed to her Akron speech—“Ain’t I a woman?” That refrain was later put in print by Frances Dana Gage, who in 1863 used it to tell a sensationalized story about Truth that she hoped would rival another told by Harriet Beecher Stowe, “The Libyan Sibyl,” published that same year. When she took the podium, Truth risked having her words misrepresented and mythologized. Unable to read, she did not write out her speeches nor could she correct the transcriptions produced by others. Still, she spoke plenty, always emphasizing that she was neither a symbol nor just like white women. In 1858, she bared her breasts before an Indiana audience, driving home the fact that she was capable of nursing children—her own and those of white women—the surest test of a woman. When Black women like Truth spoke of rights, they mixed their ideas with challenges to slavery and to racism. Truth told her own stories, ones that suggested that a women’s movement might take another direction, one that championed the broad interests of all humanity.26

IN THE 1850S, a new generation of women entered public culture, young women who had been raised in the bosom of women’s activism in antislavery societies, churches, and beyond. Sometimes the torch was passed from mother to daughter, but young women also found models in women preachers, lecturers, and writers. The first generation linked arms with the next to build a momentum that carried Black women forward. In the rough-and-tumble politics of the colored conventions movement, Black women provoked frank debates as they aimed to take seats alongside men. They met opponents who wanted to push them back into narrow roles and demanded women sacrifice their rights as women—the price of being made agents of antiracism. It was a bind.

The colored conventions exploded during the 1850s, and women seized upon the opportunity. As meetings sprung up locally, statewide, and nationally, women staked their claim. If they had once stood on the sidelines, now Black women arrived expecting to take part as delegates and members of the voting body. The door opened just wide enough for some to slip in during the 1855 National Convention of Colored Men. When it came time to call the roll, two women from Philadelphia took their seats as delegates. Then, Massachusetts abolitionist Charles Remond, whose own sister, Sarah, was a well-known abolitionist lecturer, proposed that Mary Ann Shadd Cary be admitted as a “corresponding member” of the convention, a member on paper rather than in person, who would represent those exiled in Canada. A full-blown debate ensued, with men speaking for and against Cary’s admission. The final vote of 38 to 23 went in Cary’s favor, but also admitted the matter was not settled. Cary showed no gratitude and instead criticized the convention, writing in the Provincial Freeman that it “was quite a disorderly body, and broke up without doing a great deal.” Her tone suggests one reason why her nomination may have been controversial.27

Barbara Ann Steward was nineteen years old when she headed to the 1855 Convention of the Colored People of the State of New York, but she did not get there all on her own. Even at that tender age, Steward had big ambitions and expected to be seated as a delegate. Her confidence grew out of her upbringing as the daughter of entrepreneur and antislavery activist Austin Steward. She was no stranger to the collision of issues and concerns that confronted African American leaders. She also benefited from the influence of spiritual mothers, including activist Mary Jeffrey who helped open the door to Black politics for Steward. Through Jeffrey’s example, Steward saw up close how a woman claimed her place in Black politics. Both battled for their chance to vote and hold office.28

In the 1840s, Mary Jeffrey was a young mother in the upstate town of Seneca, New York, who spent most of her days home with her son and husband, both named Jason. The elder Jason Jeffrey worked as a porter and later as a waiter. His political career preceded hers. In 1843, he attended the National Colored Convention in Buffalo, New York, and by winter of 1848, he was a member of the Western New-York Anti-Slavery Society. Jason was part of a political community in which women and men stood on equal footing, though no Black women had tried to join this Upstate New York antislavery circle.29

In 1852, Mary Jeffrey entered politics, much like Hester Lane had done in New York City a decade earlier. She donated monies to support Frederick Douglass’s newspaper and took credit for her financial contributions in her own name: “Jason Jeffrey and Mrs. Jeffrey, 50 cents each.” By the next year, something had shifted. Jason Jeffrey attended the 1853 National Colored Convention in nearby Rochester, but he did not go alone. Mary Jeffrey made the trek with him, and not simply to serve meals or otherwise attends to men’s needs. At the urging of Frederick Douglass, Mary Jeffrey was seated as a delegate—the only woman—and she did so while escaping ridicule.30

Later that same year, 1853, in December, young Barbara Ann Steward and Mary Jeffery met up at another convention, this one held in Geneva, New York. The convention not only seated both women as delegates, positioning them equals to the men. It also elected the women officers, with Jeffrey as a vice president and Steward as secretary. Steward took to the podium and delivered a formal address recorded as “able and eloquent.” Frederick Douglass recognized Steward’s potential as an antislavery speaker, and she was soon on tour through the small towns of Upstate New York: Hopwell Center, East Bloomfield, West Bloomfield, Victor, and Geneva.31

Jeffrey had paved the way for Steward’s political career, and it made a difference. In 1855, Stewart attended a mass meeting of Black residents in Douglass’s hometown of Rochester. The subject was voting rights, and much of the discussion concerned an odious property requirement that kept many Black men from the state’s ballot boxes. Stewart was the featured speaker, a young woman spokesperson on men’s voting rights. Her remarks on “the Rights and Wrongs of her suffering people” were “favorably received.” The road ahead was not entirely smooth, however. In 1855, when Steward arrived in Troy, New York, to be seated at the Colored Men’s State Convention of New York, she might have expected a cordial welcome. After all, among those hosting the meeting was her friend Frederick Douglass. Instead, delegates confronted Steward and did not mince words when they revoked her credentials and expelled her from the meeting for “no other reason than her sex.” The presence of a woman, even a proven antislavery advocate, threatened to undercut or distract the deliberations. The pronouncement—“this is not a Woman’s Rights Convention”—rang from podiums and rolled off printing presses so often that it was a familiar refrain in the 1850s. The sentiment was clear: women like Steward would not find an easy home in a political culture that associated women with the disruptive matter of their rights.32

ALONG WITH ENSLAVED men and children, women faced the demand that they labor without compensation as persons with a price. And so, enslaved women like their free counterparts also aspired to win liberty, equality, and dignity. Slavery exacted an especially high cost from women, who fought for the right to bodily integrity, in law and in life. Their bonds came in the form of shackles, ropes, pens, and the isolation of a small rural farm or a vast and remote plantation. Slavery weighed on the minds of people held in bondage through the threat of sale or the separation of family members. Their bodies endured torture meted out with a lash, a switch, the toes of a boot, or the back of a hand. Lawmakers drew boundaries that cut into enslaved people’s personhood, from restrictions on reading, writing, and worship to the strict regulation of coming and going of all sorts. Amid this, enslaved women still managed to tell their stories, in their own ways. They expressed what they thought in what they did and in rare cases created a record of their lives with pen and paper. They had a distinct story to tell about what it was to be enslaved and what women’s rights might mean. First and foremost, that meant being liberated from the threat of rape.

Though often far from convention halls, enslaved women put the problem of sexual violence before the public eye when they resisted. A woman named Celia, young and alone in central Missouri, earned notice when she killed her owner after years of being raped by him. Harriet Jacobs penned her fugitive slave narrative, one of the few written from a woman’s perspective, recounting her harrowing escape from an owner’s sexual advances. Their stories joined those of women like Sojourner Truth to make clear that control over their bodies and their intimate lives was, for enslaved women, a problem that a movement for women’s rights should remedy. Delegates to the 1851 Akron women’s convention recognized the issue, and they expressed sympathy for the “most grossly wronged” and “foully outraged of all women.” Free women understood the stories that enslaved women needed to tell.

Too often, enslaved women’s bodies were understood to be the property of slaveholders, men who claimed unlimited and unbridled authority over the women they held. In the notorious case of State v. Mann, North Carolina’s highest court reviewed the shooting of an enslaved woman named Lydia. She had been shot from behind and wounded while running away from a punishment of whipping. It’s difficult to say why Lydia believed she had a right to flee and avoid a harsh and perhaps unjust punishment. When she ran for her life, she gave judges an opportunity to impose limitations upon the man who had assaulted her. But they did not. In the words of Justice Thomas Ruffin: “The power of the master must be absolute, to render the submission of the slave perfect.”33

Mary Ann Shadd Cary’s Provincial Freeman took note of the fate of Celia, enslaved in central Missouri: “A colored woman, named Celia, was hanged on the 21st ult., at Fulton, [Missouri,] for the murder of Robert Newsom, whose slave she was in June last. The evening preceding her execution she made a full confession of her crime.” It was a cryptic report and perhaps this is all Cary knew about Celia; her Canada West office was a long way away from Missouri. Cary likely picked up the story from another paper. She could not tell her readers the more detailed tale that Celia’s trial record reveals: Celia had killed her owner in an act of self-defense after enduring years of his sexual abuse. Her owner, “the old man, had been having sexual intercourse with her.… Her second child was his.” He had first “forced her” years earlier, after purchasing Celia in a neighboring county. She had wanted to “hurt him, not to kill him” and had warned her owner “not to come,” that she was “sick.” The young woman had confessed that she struck him “twice on the head with a stick, and then put his body on the fire and burnt it nearly up.… She took up the ashes and bones [and] emptied them on the right hand side of the path leading from my cabin to the stable.”34

No one disputed Celia’s story. But they did doubt that she was a woman, at least under Missouri state law. Instead, she was property. When Celia killed her abuser, she claimed ownership of her body as a woman and drew a boundary that ran contrary to her owner’s desires, and perhaps his expectations: “He had told her he was coming down to her cabin that night. She told him not to come and that if he came she would hurt him.” Her perspective was no secret; it was not a quiet objection held private and close. Everyone in the household—a small, slaveholding family that spanned three generations—knew of Celia’s grievance: “She had told the (White) family. (She said she was threatened.)” The young woman did not harbor a silent complaint. Instead, Celia appealed to what she hoped was a shared sense of propriety: she warned “she would hurt him if he did not quit forcing her while she was sick.”35

Celia’s case began in the rooms of a rural farmstead, but the final judgment would take place in the county courthouse. What had once been family matters became public fare. Celia was repeatedly interrogated, once by a local attorney, and then again by a neighboring farmer. Both would testify at trial. Finally, she faced the Justice of the Peace, before whom she would swear to the truth of her story, affixing her mark, an “x,” to a sworn statement: “She killed her master on the night of the 23rd of June 1855 about two hours after dark.” The dispute presented to a Callaway County jury did not depend upon the proving of facts—no one disputed that her owner had habitually raped her and that, on the fateful night, Celia had refused his insistence with a warning and then a stick.36

Celia had her say, but in the courthouse her lawyers did the talking. They took her story and molded it into a defense that might save her from execution. Celia’s lawyers presented the judge with their theory broken down into four critical parts. First, if Celia had killed to avoid rape she was not guilty: “If the Jury believes from the evidence that Celia did kill Newsom, but that the killing was necessary to protect herself against a forced sexual intercourse… they will not find her guilty of murder in the first degree.” Second, rape was an offense against which a woman in Missouri may act in self-defense: “An attempt to compel a woman to be defiled by using force, menace, or duress, is a felony.” Third, Missouri law prohibited the rape of enslaved women: “The using of a master’s authority to compel a slave to be by him defiled, in using force, menace and duress.” And fourth, the law made no distinction between women: “The words any woman in the first clause of the [law] embraces slave women, as well as free White women.”37

Celia was entitled to lawfully defend herself against an owner’s sexual aggression, her legal team argued. But the judge refused to let her lawyers put this theory to the jury. Instead, he ruled that Celia did not share in the rights held by other “women” in the state of Missouri. As a “slave” woman, she was not equal to “free white women” before the law. She could be brutalized and raped, and in legal terms she could not be “defiled by using force, menace, or duress.” What her owner had done to her was not a crime, the trial judge concluded. In the months that followed, an appeals court agreed. Celia was executed in December 1855.38

Celia told her story under desperate circumstances: she was on trial for murder. The demands of the law squeezed this and other stories told by enslaved women into narrow forms such as testimony, causes of action, and statutes. Harriet Jacobs managed to defy such constraints and instead used her own pen and paper to tell her version. She too fought hard against the threat of sexual assault, and lived to tell a story that connected the rights of enslaved people to the rights of women. Jacobs had her own story to tell about years spent barely avoiding the sexual advances in her owner’s household. She was enslaved in Edenton, North Carolina, where she lived proximate to free family members who attempted to shelter her as a young girl. They could not, and Jacobs was left to devise her own escape when faced with an impossible choice: give in to the man’s demands, or be sold away far from her loved ones.39

Jacobs had no easy options. She launched a scheme of first entering into a sexual liaison with a white man, by whom she bore two children, believing that he might then aid the three to secure their freedom. Jacobs then turned to her family, a grandmother nearby, who agreed to hide Jacobs from her owner. And there she remained, in a crawlspace under the roof of her grandmother’s home, for seven years. When the opportunity to flee finally came, Jacobs headed to free soil—Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, where she spent precarious years as a fugitive. Her acquaintances included sympathetic white people and radical antislavery activists. When others, including Harriet Beecher Stowe, expressed interest in penning her story, Jacobs decided to write it herself.40

By 1855, the same year that Celia was hanged in Missouri, Jacobs’s freedom had been purchased, and she labored as a child’s maid in a New York City family. She was also at work finding her voice and crafting her story, penning a memoir of slavery and freedom in the evenings. It was, as she told a friend, a risky—even compromising—undertaking. Jacobs feared that should she confess her personal history of near sexual assault and a liaison outside of marriage—though circumstances all too ordinary for an enslaved woman—the free women of the North would judge her, shame her. Perhaps it was out of bounds for Jacobs to expect that she might live free from sexual assault, choose her intimate partners, and resist unwelcome overtures, even to the degree that she might risk running away. Her circumstances were only hinted at during women’s rights meetings in the North, and Jacobs ultimately told a hard truth about what it meant to grant that enslaved women too had rights.41

IN 1854, THE poet and antislavery lecturer Frances Ellen Watkins Harper arrived at Boston’s African Meeting House, where Maria Stewart had faced down her critics twenty years before. Harper’s visit was altogether different. She took command of the podium and delivered a lecture on Christianity followed by the reading of an original poem. Men followed her on the same stage, including local minister and Harper’s mentor, the journalist and antislavery activist William Cooper Nell, who provided “a few words of encouragement.” Not a word of criticism was uttered. A woman’s magazine later noted that Harper’s speech tore down barriers: “It would seem that the prejudice against female speaking, which prevails still in some sections, but which we think is every day becoming less, might be laid aside by everybody, so far as to hear a colored young lady plead eloquently and powerfully for the oppressed of her race.”42

Harper did not effect the change alone, of course. She built on the work of the women before her who had been knocking on the doors of power for decades. Her approach was, however, self-styled, deploying a gloved hand and a gentle rap. She was raised in Baltimore under the watchful eye of an uncle, William Watkins, a newspaper correspondent, minister, teacher, and abolitionist. Her girlhood home had been abuzz with the goings-on of African American politics. Harper spent time as a schoolteacher in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, but that was not enough to satisfy her ambition. Like many of her generation who had been raised free, she deeply identified with those still in bondage. Her talents, she determined, would go to serving the slaves’ cause and Harper joined the antislavery lecture circuit in 1853.43

Her success was one part style. Harper exhibited unassailably ladylike comportment even as her ideas were sharp and highly political. Audiences admired her “unassuming manners, graceful oratory, fervency, pathos, and truthfulness.” She delivered “outbursts of eloquent indignation” in a “style of speaking, which is highly poetical [and] quite touching and effective.” Listeners responded: “The address, coming from a gifted daughter of this despised and down-trodden race, possessed a freshness and reality which no other circumstance could so well impart. Her words fall on the hearts of those who hear her, in a manner that cannot fail to be appreciated.”44

Harper avoided the vexed confrontations that many women before her had faced when they assumed power in public. Her peers still battled, meeting by meeting, to be included in the colored conventions. Harper appeared there, too, and then waited until she was “requested to take part,” during the 1858 Ohio State Colored Convention. Harper remained close to her uncle William and their relationship taught her how to build alliances with the men who still dominated the antislavery circuit. Her mentor and traveling companion, William Cooper Nell, reported on her successes—even boasted about them: as “a colored American, and… a woman… [she] had attractions for and should be heard by the masses.” Before the decade was over, Harper had shared the podium with many of the era’s best-known antislavery speakers, men like H. Ford Douglass, Robert Purvis, Charles Remond, William Still, and William Howard Day. She also came to know white women lecturers such as Lucretia Mott and Josephine Griffing.45

Appearing on the antislavery stage was not easy. Harper generated controversy as audience members debated whether she, with all her talent and refinement, really was a woman equal to her white counterparts. In Randolph County, Indiana, the answer was no. Following Harper’s appearance there, a commentator remarked that she was very welcome to a local school, the Farmers’ Academy, as a speaker. However, “feelings of prejudice” meant that she and other Black women would be rejected as a matter of “principle” should they apply there to be students. The overriding “principle” was racism. Harper was parodied by Southern and antiabolitionist journalists. One dubbed her “a mulatto girl” that “argues that the surest and quickest way of placing the colored race in the position to live without labor, is, for the White folks to abandon the use of sugar and cotton, and other products of slave labor.” Mulatto was a slur.46

Harper spent many months on the road, where threatening confrontations with drivers, conductors, and engineers loomed constantly. In 1858, Harper marked her fourth year on the lecture circuit and had seen a lot: “I have been insulted in several railroad cars.” In these moments, her ladies’ gloves came off: “The other day… the conductor came to me, and wanted me to go out on the platform. Now, was not that brave and noble? As a matter of course, I did not. Some one interfered, and asked or requested that I might be permitted to sit in a corner. I did not move, but kept the same seat. When I was about to leave, he refused my money, and I threw it down on the car floor, and got out, after I had ridden as far as I wish. Such impudence!”47

Assaults on her dignity accompanied the physical dangers. Harper left readers to imagine her fears when she remarked, “On the Carlisle road, I was interrupted and insulted several times. Two men came after me in one day.” Recalling this confrontation for a friend, Harper was a bit more frank: “I hardly think that I shall be at your meeting after all. The distance is far, and the road most accessible that I know of, is proscriptive to colored persons. I was interrupted and insulted on it Monday this week—the Cincinnati and Carlisle road.” No number of lace cuffs or carefully tailored dresses could protect Harper from violence. At a meeting in Cool Spring, Ohio, “an attempt was made to break up by rowdy violence, one of Miss Watkins’ meeting.” Her hosts had the offenders arrested.48

The root cause of the mob’s objections came through during the court proceedings that followed. Yes, Harper sued. The attorney for the defendants asked one witness, a white man, “Are you a nigger worshiper?” Rather than sanctuaries, courtrooms permitted the insults to her dignity to continue. She stayed in town to testify against the men who had disrupted her remarks and threatened her harm. The court required Harper to repeat her lecture for the jury so that it might determine the “character of the meeting.” The trial ended in favor of Harper and her right to lecture. But that victory did not mean she was safe. Harper continued to speak about politics willingly, and she influenced hearts and minds. And still, she had to endure a distinct mix of threat and danger. She may have not been boxed in, but neither was she free.49

BY THE END of the 1850s, when Black women exercised their power, they might have faced opposition, but no longer was anyone surprised. They had made themselves visible at public gatherings—church conferences, political conventions, benevolent society meetings. They still served meals or attended to the comfort of a speaker or delegate. But they also insisted on claiming their own time at the podium and during deliberations. Black women challenged the politics of the 1850s by what they did and by what they said. They were loyal to organizations in which they could battle against both racism and sexism. They crafted their own definition of women’s rights, one drawn from their experiences with the indignity of forced labor, the scourge of sexual assault, and their rough handling on streetcars and trains. These critiques steered the course of a new women’s movement, one with Black women at the helm.