To most people, Hong Kong’s history starts with the Opium Wars in the 1840s. However, archaeological studies have uncovered evidence of human habitation along this stretch of the southern Chinese coast dating back some 6,000 years.

Most of the excavated stone tools, pottery and other artefacts have been found preserved in coastal areas, suggesting a strong dependence on the sea. Bronze appeared in the middle of the second millennium bc, and weapons and tools such as axes and fish hooks have been excavated from local sites. There is evidence, too, in the form of stone moulds from the islands of Chek Lap Kok, Lantau and Lamma, that the metal was worked locally. Rock carvings, most of which are geometric in style, have also been discovered around Hong Kong Island and on some of the smaller islands.

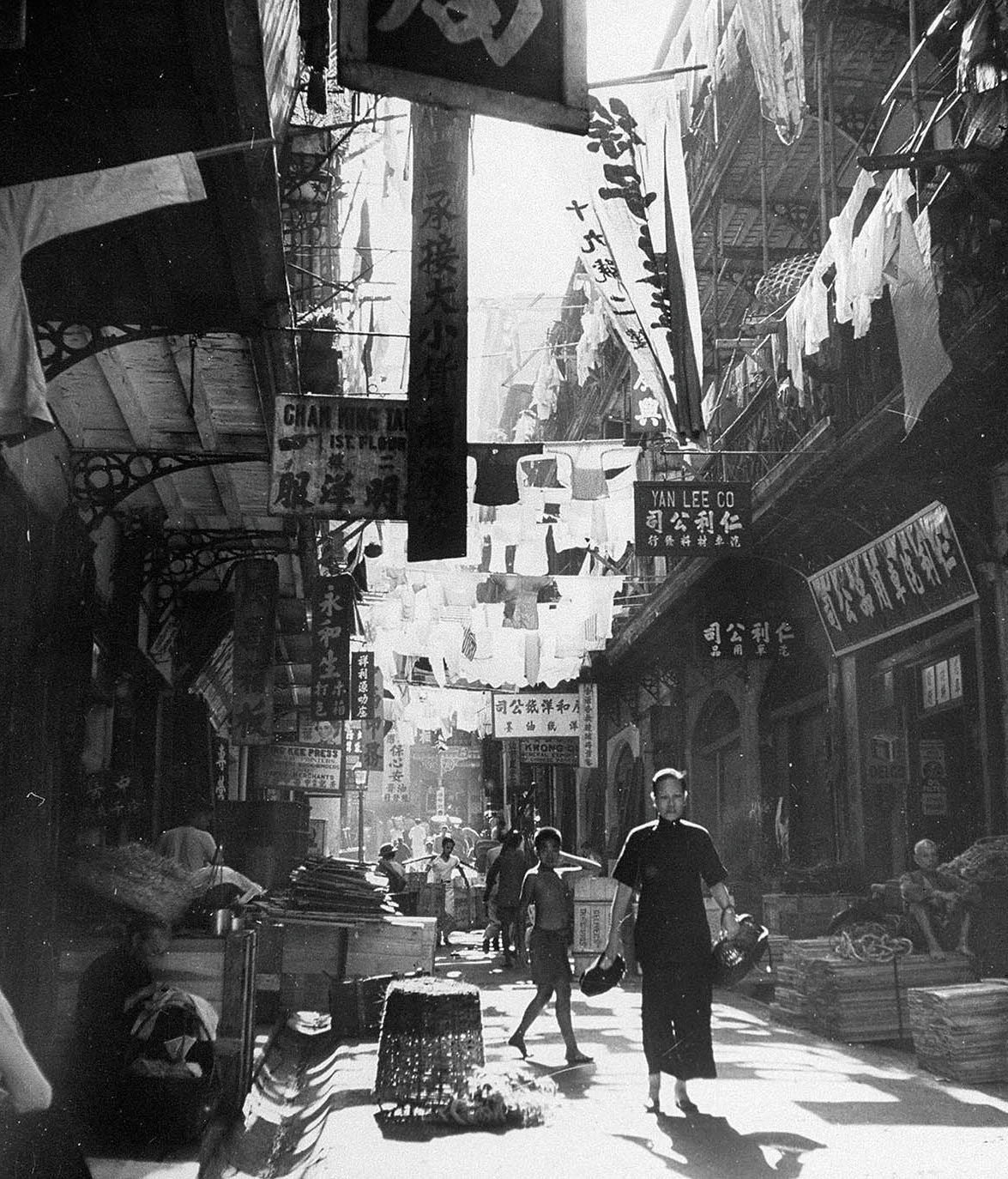

Laundry hanging across the streets, 1941.

Getty Images

An increasing number of people from the mainland came to settle in the region during the Qin (221–206 BC) and Han (206 BC–AD 220) dynasties. Coins of the Han period have been found in Hong Kong, and a brick tomb was uncovered at Kowloon’s Lei Cheng Uk (for more information, click here) with a collection of typical Han tomb furniture. Other findings included pottery and iron implements. Little has been discovered from the next 1,000 years, but engraved writings, coins and celadon pottery suggest strong links with the Chinese Song dynasty during the 13th century. The many Ming-style blue-and-white porcelain works discovered on Lantau suggest increasing contact with the mainland during the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties.

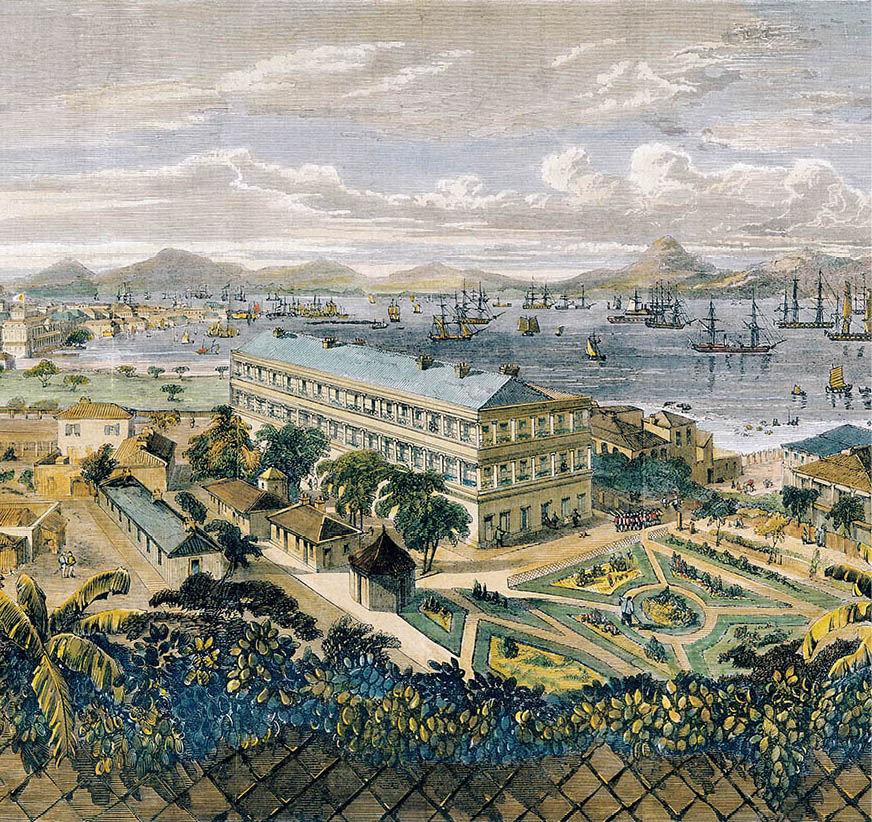

Early colonial buildings on the harbour, 1856.

Mary Evans Picture Library

The coming of the Europeans

The West began to show an interest in China and Asia during the 15th and 16th centuries due to the increased trade in products such as silk and tea. The Portuguese were the first to arrive, trading with China at various points along the coast and establishing a settlement at Macau in 1557. The British, on the other hand, did not appear in force until the latter part of the 17th century.

In 1685, Emperor Kangxi, who reigned when the Qing dynasty was at the peak of its power, opened Guangzhou for limited trade. Ships began arriving from the British East India Company stations on the Indian coast, and soon Hong Kong, with its deep-water harbour, began to establish itself as a trading hub. Fifteen years later the Company, the world’s largest commercial organisation, received permission to build a storage warehouse outside Guangzhou.

Early trade with Europeans

To begin with, in the early 18th century, trade with Western countries was in China’s favour. Traders paid huge amounts of silver for fine Chinese tea and silk products, for which there was great demand in Europe. Tough terms were imposed on foreign traders, considered to be barbarians. They could only live in restricted areas in Guangzhou. They could not bring in arms, warships or women. Learning the Chinese language was forbidden, and traders also had to put up with the Chinese system of royalties, bribes and fees. Furthermore, local merchants were appointed by the emperor to keep an eye on foreigners.

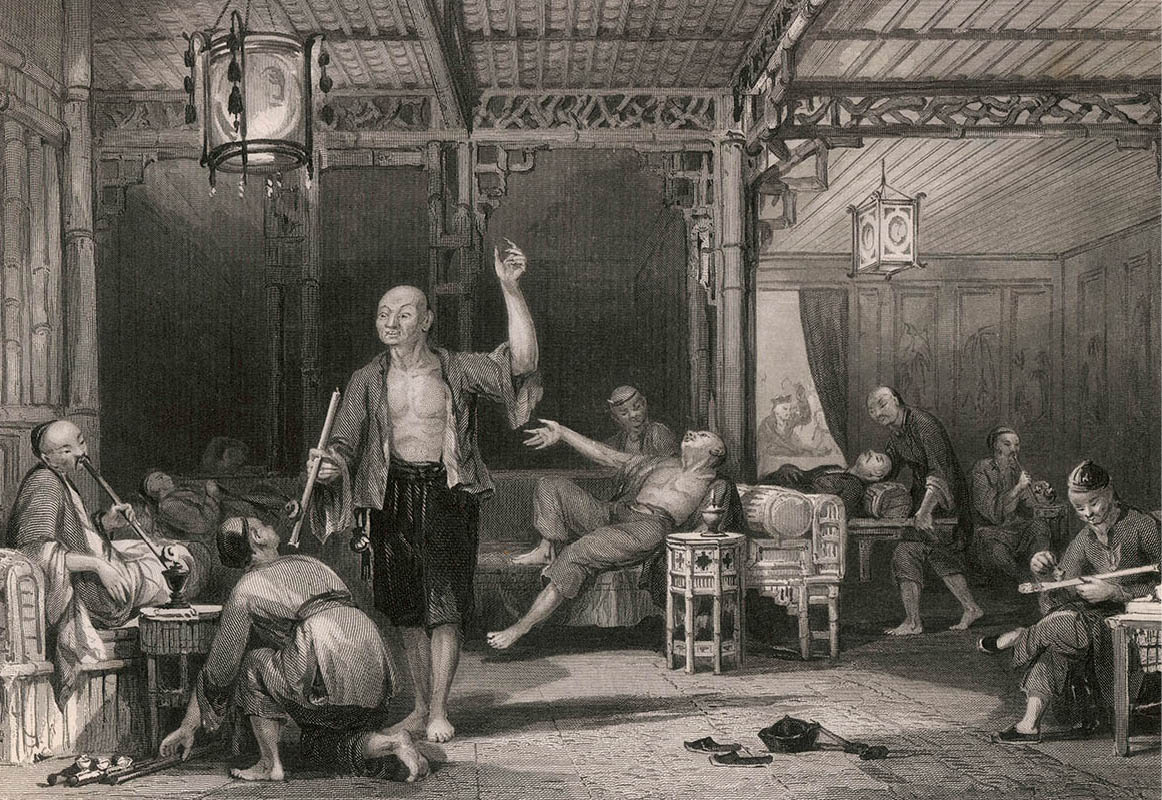

19th-century opium addicts.

Mary Evans Picture Library

After more than a century of trading with China, the East India Company tried to balance its increasingly expensive purchases by developing its profitable sale of opium to the Chinese, mostly shipped from their colonies in Bengal. By the beginning of the 19th century there were already millions of addicts in China, and the country was paying for its spiralling drug habit with silver specie, disastrously depleting the national treasury. Clearly, from a Qing perspective, something had to be done.

Alarmed at the increasing outflow of silver, the emperor Jiaqing banned the drug trade completely in 1799. In 1810 he went further, announcing: “Opium is a poison, undermining our good customs and morality. Its use is prohibited by law.” But neither foreigners nor Guangdong merchants were willing to give up the profitable business, and they resorted to smuggling. By 1820, the trade had grown to 30,000 chests annually.

Jiaqing’s son, Daoguang, continued to issue edicts after he came to the dragon throne in 1820, but to no avail – the British weren’t listening, and nor, apparently, were the opium addicts. Accordingly, in 1838 Daoguang dispatched Lin Zexu, the formidable Governor-General of Henan and Hubei, as his commissioner to impose Qing anti-opium legislation on the unruly foreign traders in Guangzhou. To the fury of the Westerners – at whose head stood the British – Lin confiscated and destroyed more than 20,000 chests of opium and blockaded the port to foreign shipping. Lin also wrote to Queen Victoria, asking why the British prohibited opium imports into their own country, but forced it on China. “Was this a morally correct position?”, the commissioner asked rhetorically.

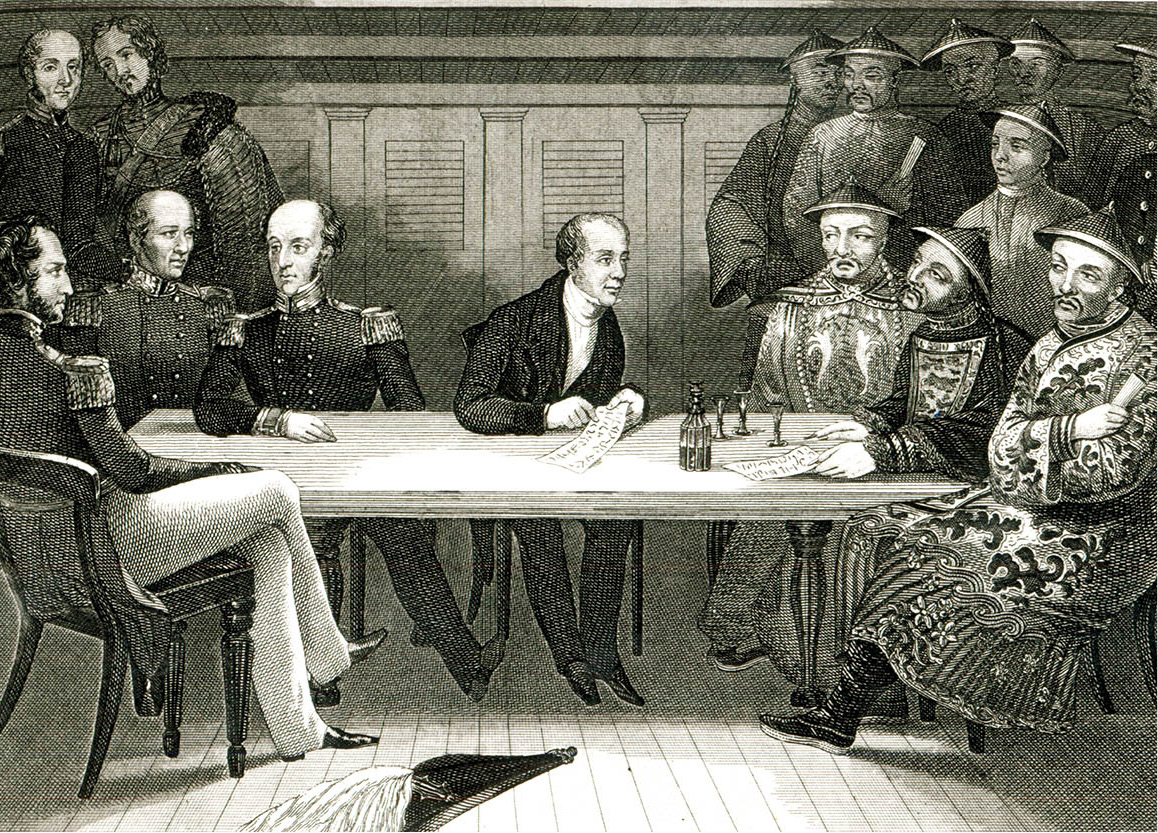

The British demand the opening of China’s ports.

Bridgeman Art Library

Lin’s letter was never delivered to the queen, although it was published in The Times. And while it may have given liberal anti-opium campaigners in Great Britain pause for thought, it raised no sympathy at all with the opium merchants of India and Canton, who loudly demanded compensation for their lost opium, and pressed for military retaliation. This came in 1840, with the arrival of warships and soldiers from India. European military superiority ensured the First Opium War (1840–42) was short, sharp and one-sided. The British seized control of Guangzhou. Intimidated, the Qing commissioner, Qi Shan, who had replaced Lin, agreed in January 1841 to the Convention of Chuen Pi, which ceded Hong Kong Island to Britain. On 26 January 1841, the British flag was raised at Possession Point on Hong Kong Island, and the island was officially occupied. Five months later, British officials began selling plots of land and the colonisation of Hong Kong began.

The name “Hong Kong” is derived from the Cantonese Heung Gong, which means “fragrant harbour”. In the past, sandalwood incense was produced around what is now Aberdeen, and the scent drifted out to sea.

Neither China nor Britain was happy with the terms of the Chuen Pi agreement, however. The Chinese government and its people saw the loss of a part of its territory as an unbearable humiliation, and Qi Shan was ordered to Beijing in chains. The British government, particularly Lord Palmerston, the irascible Foreign Secretary, was unhappy with Hong Kong, which he contemptuously – and famously – described as “a barren island with barely a house upon it”, and refused to accept it as an alternative to a commercial treaty.

Blaming Captain Charles Elliot of the Royal Navy for failing to make full use of the troops sent to China, Palmerston replaced him with Sir Henry Pottinger, Hong Kong’s first governor, in August 1841. Pottinger soon realised Hong Kong’s potential future, even though Britain had treated it as just another pawn in ongoing negotiations with the Chinese. He encouraged long-term building projects and awarded land grants.

Hong Kong became a British colony in three stages: Hong Kong Island (1841–2) was followed by the Kowloon peninsula (1860), then New Kowloon and the New Territories were leased for 99 years (1898).

After Shanghai fell in 1842, the Qing authorities sued for peace, and the Treaty of Nanking was signed in August, formally transferring Hong Kong Island to the British “in perpetuity” (the Chuen Pi Convention of the previous year had not been signed and so was never accepted as an official agreement by the British). As well as awarding the British 21 million ounces of silver in compensation for the opium seized three years earlier, the treaty also opened five “Treaty Ports” to foreign shipping and residence including Guangzhou, Xiamen and Fuzhou, Ningbo and Shanghai. Suddenly China was exposed to a new and troublesome “enemy at the gate”. Subsequently, with the silting of Macau’s harbour and the weakening of Portuguese power in Asia, Hong Kong began its growth into one of the greatest port cities the world had ever seen.

Storming the fortress at Xiamen (Amoy) in 1841.

The Art Archive

The early colonial period

In its early days, the new British colony grew slowly, but further Anglo-Chinese conflict was soon to change this. In 1856 a dispute over the interpretation of the earlier treaty led to the outbreak of the Second Opium War, and during the two-year conflict, many companies in Guangzhou transferred their offices to Hong Kong, considerably strengthening the fledgling colony. China, weak with a corrupt government, lost again. By the summer of 1858, allied British and French troops had advanced far to the north, forcing the Chinese government to sign the Treaties of Tianjin (Tientsin). The terms gave foreigners the right to send diplomatic representatives to China and travel freely throughout the land.

A panorama of Victoria Harbour from 1860.

Getty Images

Hostilities were renewed the following year when Chinese soldiers fired on the first British envoy to China as he made his way to the court in Beijing. Fighting continued until 1860. The British consul in Guangzhou secured the perpetual lease of the Kowloon peninsula all the way north to what is now Boundary Street, including Stonecutter’s Island.

By this time, other countries – Russia, France, Germany and Japan – were waking up to the importance of having easy access to China. Not to be outdone by the British, they began to make similar incursions to secure footholds all along the Chinese coastline. In 1862, a Sino-Portuguese treaty gave Macau a colonial status similar to that of Hong Kong. A second treaty in 1887 confirmed it as a Portuguese colony in perpetuity.

The British were concerned that their territory in Hong Kong was vulnerable to attack from the north, and wished to gain control of the mountainous area north of Kowloon as far as the Shenzhen River. In 1898 they got their way, securing the lease of what became known as the New Territories (as well as some 230 islands) for a period of 99 years. There was later regret at having signed this treaty, which only leased the land, while Hong Kong Island and the Kowloon peninsula were British in perpetuity. (It would later be impractical for Britain to keep Hong Kong Island and Kowloon when the New Territories lease ran out in 1997.)

At first, Chinese warships were allowed to use the wharf at Kowloon City, and Chinese officials were permitted to remain in office. However, a year later, the British took over the city completely. The New Territories was declared a part of Hong Kong, although it kept a separate administrative body from the urban area. Under a laissez-faire style of British rule, Hong Kong people were left alone to concentrate on their businesses.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the colony developed rapidly, becoming a magnet for immigrants and a centre of trade with Chinese communities abroad. Several public-service companies were established, including the Hong Kong and China Gas Company in 1861, the Peak Tram in 1888 and the 137-km (85-mile) Kowloon-Canton Railway (KCR) in 1910. The paucity of land for building due to the steep terrain meant that land-reclamation projects got under way as early as 1851. In 1904, the first land reclamation was completed in what is now the area of Chater, Connaught and Des Voeux roads. In 1929, another reclamation project was completed in Wan Chai. Today around 6 per cent of Hong Kong’s land has been reclaimed from the sea.

Turbulent times

From the beginning of the 20th century, China experienced a series of political upheavals. In 1900, a peasant uprising known as the Boxer Rebellion seriously challenged the authority of the creaky and corrupt Qing government, which collapsed for good a few years later. In 1911 Sun Yat-sen established the Republic of China. (Although Sun Yat-sen travelled to Hong Kong many times to enlist support for his cause, his revolution did not have much impact on the British colony.)

The Prince of Wales is carried in a Chinese litter through the streets en route to Government House, 1922.

PA Photos

Between 1920 and the late 1940s life in China was dominated by conflict. The long-running civil war between Mao Zedong’s Communist Party (founded in 1921) and the Nationalists (Guomintang), led by Chiang Kaishek, divided the country. The Japanese invasion in 1937, and World War II, brought terrible suffering. In December 1941 Japanese troops attacked Hong Kong from the north; Allied forces withdrew from the New Territories and Kowloon to Hong Kong Island. After 18 days of fighting, the British forces surrendered on Christmas Day. The Japanese Occupation lasted for three years and eight months, during which time all British and Allied nationals were interned in camps and two-thirds of Hong Kong’s Chinese population fled to China.

The divide between the British colonial administrative and business districts (Central) and the Chinese commercial “bazaar” areas (Western) were well established by the 1860s and can still be discerned today.

During the occupation, Hong Kong’s trade virtually stopped, the currency lost its value and food supplies were limited. Chinese guerrillas fought against the invaders in the New Territories, and villagers helped foreigners to escape. Under an agreement between Japan and Portugal, Macau became neutral territory, and some Europeans found refuge here during the war.

In August 1945, after the Japanese surrender, the Royal Navy arrived in Hong Kong to re-establish British rule over a battered colony with a population of just 600,000.

Post-war Hong Kong

After the war, Hong Kong Chinese who had escaped to those mainland areas beyond Japanese control returned in large numbers. China’s civil war, which resurfaced in 1946 soon after the Japanese surrender, drove more people – including affluent Shanghai entrepreneurs, shipping magnates and property tycoons – into the British territory. By 1949, the population had swelled to 2 million.

Refugees and migrants

For much of the 20th century, Hong Kong was a place of refuge from the chaos in China. The civil war of the 1930s brought large numbers of refugees from southern areas, but this paled in comparison with the influx that took place between 1945 and 1950, when more than 1.5 million Chinese flooded south. This expanded the supply of cheap labour, though a significant number of émigrés were savvy businessmen, notably from Shanghai. Seen as modern-day rivals, Hong Kong and Shanghai share a deep affinity, born of this post-war influx, and many aspects of modern Hong Kong culture can be seen as a continuation of a Shanghai culture that existed before 1949 and the Communist revolution.

After 1950, regulations were introduced to limit numbers, yet throughout the 1960s and ’70s people continued to arrive at the Lo Wu border post, desperate to escape poverty. Some succeeded, but after numbers shot up between 1978 and 1980, the door was firmly shut. The focus then switched to the Vietnamese boat people, arriving by sea and housed in refugee camps until forced repatriation in the 1990s. Post-1997, movement between the PRC and the SAR is controlled, but fluid. For more on immigration, for more information, click here.

In October 1949, Mao Zedong declared the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, and the defeated Nationalists fled to Taiwan. The United Nations imposed an embargo on trade with China, with serious consequences for Hong Kong’s economy. A shift to manufacturing proved its saviour, with the hundreds of thousands of refugees providing cheap labour for textile factories set up by Chinese entrepreneurs.

With hundreds of thousands of people living in squatter camps, a series of fires culminated in the1953 Shek Kip Mei fire, which left 53,000 homeless and led the colonial government to fast-track its public housing policy. Soon the first high-rise New Towns were being planned and developed.

By the 1960s the textile and garment industries accounted for more than half of the colony’s exports. The manufacture of plastic toys also became important. At the same time, the situation in China was becoming ever more desperate, with famine bringing another wave of immigrants to Hong Kong. This time the numbers were alarming, and the colonial government tried desperately to keep them out. For most of the Hong Kong population, the standard of living continued to rise during the 1960s, in stark contrast to their relatives on the mainland.

During the Vietnam War in the late 1960s and early 1970s, US Navy vessels, en route to or from Vietnam, were a familiar sight in Victoria Harbour, and American soldiers headed to bars and nightclubs of the Wan Chai and Tsim Sha Tsui for R&R.

At this time, China was ravaged by the Cultural Revolution, and the turmoil drifted into Hong Kong, where tensions erupted into a series of disturbances in the mid-1960s, and also to Macau where Red Guards waged a propaganda war with posters and slogans, calling on the Chinese residents to start a revolution (pictured above). The chaos almost paralysed the economy, but by the end of 1967, the unrest had been more or less quelled.

1970s and 1980s

Starting in the late 1970s and continuing through the 1980s, Hong Kong’s economy developed at an amazing pace, as it expanded its role as an entrepôt with its neighbours and as China’s trading partner. This was made possible by greater stability in China, and the rapid economic advance there due to Deng Xiaoping’s pragmatic policies. Hong Kong began to play a vital role as China’s window to the world and the world’s gateway to China. An increasing number of local businesses began investing in factories in the PRC, where labour and raw materials were cheaper.

To keep pace with economic development, infrastructure was improved, and the territory was transformed into a modern, efficient and cosmopolitan city. The government increased its investment in education, housing and other social welfare projects. An efficient civil service system introduced by the British government played a major role in the economic boom, aided by the Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC), set up in 1974.

By the 1980s, the Hong Kong government enjoyed near-complete autonomy from London, and even had the power to conclude certain negotiations with foreign powers. The colony regularly negotiated its own economic agreements with other countries, and was admitted into several international financial institutions, such as the Asian Development Bank.

Anxieties and the build-up to dialogue with China

Amid all the prosperity, however, was an inescapable anxiety over the future, with the 1997 expiry of the 99-year lease on the New Territories looming large. By the early 1980s, life in Hong Kong was dominated by the issue of its return to China. Most of the local population would have preferred to stay under British rule rather than embrace the communist regime. Although they were unhappy with the fact that British companies and expatriates had enjoyed privileges in business and in government positions, people appreciated being able to compete in a free market. Having escaped extreme poverty or, in some cases, political persecution, they feared going back to the communist system. But their destiny was not in their own hands.

China had always maintained its stance that it would take back Hong Kong when the time was “ripe”. By the early 1980s, the moment seemed to have arrived, and Beijing became intent on expunging 150 years of humiliation.

Although China refused Portugal’s offer to return Macau in the mid-1970s for fear of destabilising Hong Kong, circumstances had changed by the 1980s. Now China’s leaders began thinking about getting Hong Kong back.

Negotiating the return

Margaret Thatcher’s visit to Beijing in 1982 formally launched the discussion on what would happen to Hong Kong after the 99-year lease on the New Territories, nine-tenths of the colony, expired in 1997. The reaction to the news that the colony’s future was being negotiated was typical of Hong Kong – the local stock market nosedived.

In September 1984, after two years of often acrimonious negotiations, Britain and China came to an agreement, the Joint Declaration, which formally agreed the return of the colony to China in 1997. The Declaration stipulated that Hong Kong’s way of life would remain unchanged for 50 years, that the territory would become a Special Administrative Region (SAR) and continue to enjoy a “high degree of autonomy” – except in foreign affairs and defence – and that China’s socialist system and policies would not be imposed. As Deng Xiaoping put it, “Horses will keep racing, and nightclub dancing will continue.”

Margaret Thatcher meets Deng Xiaoping in 1982 to discuss the Sino-British Joint Declaration.

Getty Images

Plans were drawn up for Hong Kong’s administration in the years running up to 1997. Key points included elections to the Legislative Council (Legco), the District Boards and new Regional Councils. Beijing soon appointed a committee of 59 members, only 23 of whom were from Hong Kong, to draft the mini-constitution – known as the Basic Law – for the SAR. In military matters, Britain announced it would phase out its garrison, while China said the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) would be stationed in Hong Kong after the handover.

During Hong Kong’s first Legco elections in 1985, initiated by the British, 24 of the 56 members took their places through indirect elections. Out of a total population of 5.5 million at the time, only 70,000 people were eligible to vote under Hong Kong’s restricted system of indirect elections. Of that number, only 47,000 registered to vote and only 25,000 actually went to the polls. Nevertheless, this election started a debate about whether the Hong Kong government would allow open elections to take place in 1988, as had been promised.

The democracy question and the brain drain

By the late 1980s, China was beginning to worry about the territory’s fledgling attempts at democracy. Beijing’s top man in the territory, Lu Ping, insisted that Britain was deviating from the Joint Declaration and arousing fear and anxiety amongst Hong Kong’s people. Amid the political tension, however, Hong Kong’s economy continued to thrive.

The British government wanted direct elections to be held before 1997. Increasingly irritated, Beijing eventually declared that political changes not consistent with the Basic Law would be nullified in 1997. Deng Xiaoping added that universal suffrage might not be beneficial for Hong Kong.

In June 1989, the Chinese government crushed a pro-democracy demonstration centred in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. Horrified by the brutality, 1 million people took to the streets in Hong Kong to protest.

The massacre exacerbated the Hong Kong brain drain, with large numbers leaving the territory annually in the next few years. At the end of 1989, Britain said it would grant British citizenship to just 225,000 Hong Kong Chinese before Hong Kong reverted to China. In 1990, about 60,000 of Hong Kong’s most accomplished professionals moved overseas (often to secure passports), mainly to Canada and Australia. Britain called on its allies to accept Hong Kong immigrants; the United States amended its immigration laws to increase Hong Kong’s quota to 10,000 annually until 1994 and 20,000 thereafter. The Hongkong & Shanghai Bank (HSBC), the territory’s largest, moved its HQ to Britain, generally seen as reflecting the company’s lack of confidence in Hong Kong’s future.

Funding the new airport

At the start of the 1990s it seemed that barely a day went by without some wrangling between Britain, Hong Kong and China over who was to foot the bill for the hugely expensive new airport under construction at Chek Lap Kok, off the coast of Lantau Island.

To boost the economy and restore confidence battered by the Tiananmen Square massacre, the Hong Kong government announced it would build a new airport, scheduled for completion in early 1997 at an estimated cost of HK$78 billion. China attacked the scheme, insisting that it should be consulted because its future SAR government might be saddled with debt.

Government representatives paid many visits to Beijing to win approval for the project, all the time trying not to appear as if they were grovelling. China was unrelenting. Finally, in 1991, Beijing and London announced that an understanding had been reached, although – like the 1984 Sino-British Agreement – its conclusion was without Hong Kong’s participation. China gave its support for the airport in exchange for fiscal guarantees and a place on the airport authority’s board.

Almost two decades on, it all appears to have been worthwhile – Chek Lap Kok is universally acclaimed as one of the world’s most efficient airports, and plays a large part in Hong Kong’s continuing success.

Direct elections

London tried to keep earlier promises of democratic reform without provoking China’s displeasure at free elections for Legco. Pushed by budding political awareness among its citizens, the Hong Kong government agreed to speed up the process, saying it would put 18 seats up for direct elections in 1991.

After numerous consultations, the two governments agreed in early 1990 that members elected to Legco in 1995 would serve until their term ended in 1999, two years after the handover, and that they would be among the 400 people who would select Hong Kong’s first post-1997 handover Chief Executive. China later reneged on the agreement after Governor Chris Patten carried out electoral reforms against Beijing’s wishes; China replaced the elected Legco with a Beijing-appointed provisional legislature.

Martin Lee, pro-democracy politician.

Getty Images

In June 1991, Hong Kong’s new Bill of Rights backing the “rights and freedoms” guaranteed in the 1984 Sino-British Agreement became law, despite China’s insistence that the move was against the principles stated in the Basic Law, Hong Kong’s post-handover constitution.

The first direct elections in Legco’s 150-year history took place in September 1991. For the first time, the incumbent government faced opposition and the potential of legislative defeats from the opposition under barrister Martin Lee. China, in a not-too-subtle move, advised voters to take candidates’ “attitudes toward the mainland” into account when casting their votes. The comment was widely interpreted as a call to vote for the pro-Beijing candidates and not those of the pro-democracy camp represented by Lee’s United Democrats. Unimpressed, voters demonstrated their independence by giving 15 of the 18 seats up for direct election to pro-democracy candidates.

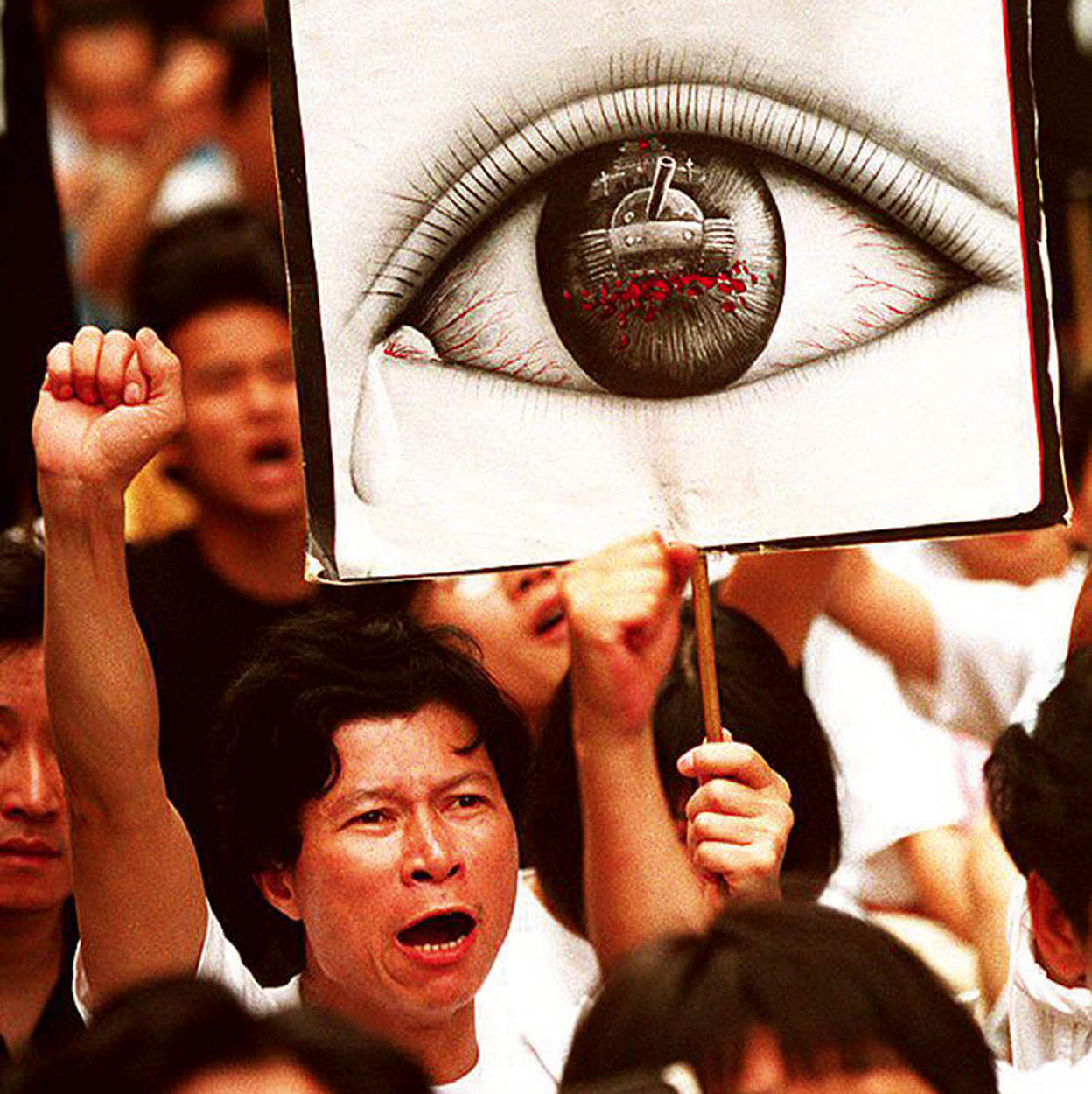

Street demonstrations following the deaths at Tiananmen Square in 1989.

Getty Images

Patten and the handover

In April 1992, Britain’s Conservative Party chairman Chris Patten was named Hong Kong’s last governor – the first time a politician instead of a diplomat had been given the post.

Patten’s arrival heralded the most tense period in relations between Britain and China. Championing the democratic rights of Hong Kong people put him unerringly onto a collision course with Beijing. A low point was reached when the Chinese government declared that all contracts, leases and agreements signed or ratified by the British Hong Kong administration without the approval of China would not be honoured after 30 June 1997, the last day of Britain’s rule. Beijing also pointed its accusing finger at the private sector, including the British company Jardines, which it accused of supporting Patten’s political agenda and damaging the international community’s confidence in Hong Kong’s future. For more on Patten and the handover, see feature.

A loophole in the Right of Abode section of the Basic Law led to many mainland relatives of Hong Kong citizens trying to be in Hong Kong by 1 July to claim residency. Migration became blurred as Hong Kong companies sought out talented professionals from the mainland, and Hong Kongers moved to China, or travelled there frequently, to take advantage of business opportunities in the new booming China.

The Hong Kong flag is lowered during the handover of Hong Kong to Chinese control after years of British colonial rule.

Getty Images

Several opinion polls taken shortly before the handover showed that most Hong Kong people would have preferred to remain under British rule if they could control their own destiny, although it was deemed politically correct to say they loved the motherland. And although many were sceptical that Beijing would keep its promise to let Hong Kong’s political system continue for another 50 years, most people had decided to accept the reality and adapt, aware that their future economic success was inextricably tied to China.

End of empire

The handover of Hong Kong to China saw more celebrations than at any other time in the territory’s history. Most Hong Kongers forgot the politics and revelled in the occasion. As midnight approached on June 30, 1997, most major figures who had, or were to have, a hand in Hong Kong’s future gathered in the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre.

Just before midnight, the Union Jack descended as the British military band played “God Save the Queen”. Chris Patten shook hands with the crowds before boarding the royal yacht. Inside the convention centre, civil servants swore allegiance to the People’s Republic of China in Mandarin.

The next morning, People’s Liberation Army troops crossed over the border, welcomed by villagers lining the roads.

Finally, the day arrived: journalists from all over the world flew in to cover the events, while there was fevered last-minute activity to complete the Convention Centre in time for the ceremony. A slightly surreal party atmosphere, building over the preceding weeks, took over.

The last governor

Chris Patten bought the savvy of a Westminster politician to London’s last major colonial outpost. His governorship was perhaps his greatest political achievement.

Chris Patten, Hong Kong’s last governor for the five turbulent years leading up to the handover, took over from David Wilson in 1992 with the avowed aim of protecting the interests of the Hong Kong people. Unlike his predecessors, who had arrived decked out in full ceremonial dress (plumed helmet and all), Patten wore a dark business suit – discreetly modernising the image of the office of governor in Hong Kong in the process. Despite, or perhaps because of some of his unorthodox ways, Patten soon proved to be a popular leader. Instead of sitting in his office, he went out into the streets to meet ordinary people, listened to their opinions, and held question-and-answer sessions in public during which he addressed politically sensitive issues with a candid, sometimes controversial attitude.

Patten announced various proposals for increased spending on welfare, health, housing and the environment. The most controversial move, however, was his proposal to reform the political system. China wanted no such shift towards greater democracy, and openly attacked Patten’s political reforms. As a result, the Hang Seng Index dropped about 5 percent in October 1992, and brokers warned that unless Patten made a U-turn on his push for greater democracy, the stock market could suffer further.

Electoral reforms

In 1994, Legco passed Patten’s proposed electoral reforms by a narrow margin, inviting strong condemnation from China. The reforms were a halfway point between full direct elections for all members of the legislature and a more muted electoral plan. Legco remained far from being a directly elected legislature, but the change was still enough to draw more criticism from China.

The electoral reform was Patten’s last major act in office. As China began to play an increasingly important role in Hong Kong society and the business sectors competed with each other to get on Beijing’s good side, Patten was sidelined. Beijing simply refused to talk to him, making it difficult for him to take any further action.

Despite the many humiliating insults the Chinese leaders threw his way during his five years in office, Patten’s political reforms and personal charisma won him the respect of Hong Kong’s residents. At the British farewell ceremony on the night of 30 June 1997, Patten’s forceful farewell speech received long applause from the crowd, and people shouted “We will miss you” as he and Prince Charles boarded the royal yacht Britannia for England.

With every passing year, the handover feels more and more like ancient history. The shift of sovereignty was followed, coincidentally, by an economic downtown, but prosperity has since returned and Hong Kong has rarely looked back as it moves forward. Patten would be proud that political awareness and civic pride have heightened over recent years. He’d also understand the basic law of Hong Kong life: the economy remains king.

Farewell speech at the British Handover Ceremony; Prince Charles looks on.

Getty Images

Post-handover

The SAR’s first chief executive was selected by a Beijing-appointed committee at the beginning of 1997 from a choice of three candidates. Tung Chee-hwa, a Shanghai-born shipping tycoon who had received financial help from China in his earlier business days, was the obvious candidate from early on. Tung – along with his Chief Secretary Anson Chan and Financial Secretary Donald Tsang – had previously been a member of the colonial government appointed by Patten.

Legco was dismantled on 1 July 1997, and replaced with a Beijing-appointed provisional legislature. After taking office, Tung announced a new voting system for Hong Kong’s first legislative election, set for May 1998, that gave the biggest say to business groups, a move believed to have been designed to sideline the most popular party, the Democrats.

Free speech (anti-Article 23) protests, July 2003.

iStock

Economic downturn and recovery

Before the handover, a popular view was that Hong Kong under communist China would undergo political changes, while remaining stable and prosperous economically. What happened in the months after the handover was just the opposite. There were few political confrontations, apart from some dissent concerning the make-up of the SAR’s first legislative body, and the PLA kept a low profile in its barracks. However, in late 1997 and through 1998 Hong Kong experienced a major economic crisis, as did many Asian countries. The Hang Seng Index dropped 6,000 points – about 40 percent.

A slow recovery began in 1999, but even by 2003 the economy was still in the doldrums, unemployment had soared and, in an ironic reversal of history, many locals began seeking work on the mainland. From March to May 2003 the SARS virus epidemic caused panic across the region – the Hong Kong public wore surgical masks and plastic gloves outdoors, and tourist numbers dried to a trickle.

As the city recovered, a growing frustration with the government’s handling of the SARS outbreak and in particular its proposal to introduce controversial anti-subversion laws brought more than 500,000 peaceful demonstrators onto the streets to protest against the plans on 1 July 2003. The plans were shelved and the minister responsible, Regina Ip, resigned within the month.

Hong Kong’s improving economic fortunes are largely thanks to the double-digit growth in China’s economy, and increased Chinese tourist arrivals. Yet this success did little to help the Chief Executive. Unable to regain the public’s confidence, Tung Chee-hwa stepped down in early 2005.

Demonstrators protesting against perceived pro-Chinese changes to the school curriculum in 2012.

Dreamstime

His replacement, appointed by Beijing, was Donald Tsang, a devout Catholic and career civil servant. Born in Hong Kong, Tsang was more comfortable dealing with press and public than his predecessor. While his popularity remained relatively high throughout his tenure, Tsang didn’t dodge controversy entirely. His political reform package attracted vociferous pro-democracy demonstrations, which demanded that a date was set for electing Legco by universal suffrage. Tsang himself was re-elected as Chief Executive in 2007 by a 800-strong committee largely loyal to Beijing.

In September 2012, Leung Chun-ying, or C.Y Leung, became the third chief executive of the SAR, elected from an expanded 1,200-strong voting committee. In contrast to previous elections, the contest was marked by tabloid-style scandal and mud-slinging. Leung was the second-choice candidate for long periods before a series of blunders and corruption allegations scuppered the chances of his rival, Tang Ying-yen. Leung faced some tough early decisions, opting to back down on plans to make all Hong Kong schoolchildren take China “patriotism” classes, and taking a hard-line on the increasing trend of pregnant mainland mothers crossing the border to give birth – both issues which had sparked protests in the preceding months.

The people of Hong Kong remain on a promise to be able to elect their own chief executive next time around, in 2017, though their choice of candidates is likely to be limited in some way by political leaders in Beijing.

Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying at press conference after his 2014 policy address.

Getty Images

One country, two systems?

In 2012 Hong Kong marked the fifteenth anniversary of the establishment of the SAR with both fireworks and a protest. Fifteen years into the 50 years of “one country two systems”, the Chinese national anthem plays at the start of the day’s television broadcast, the PRC flag flies alongside the Hong Kong Bauhinia, and the school curriculum has changed to include the Basic Law and Putonghua. Cantonese has replaced English as the language of instruction in most schools, and speaking good Mandarin is now at least as important as having good English for those looking to get on.

Beijing has, nonetheless, largely kept its promise not to interfere in Hong Kong’s internal affairs. After Tsang’s re-election in 2007, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC), China’s parliament, issued a ruling that the earliest possible date for direct elections for Hong Kong’s Chief Executive is 2017, and 2020 for Legco. While local democracy campaigners were deeply disappointed, many Hong Kongers take the pragmatic view that there is at least some kind of date on the table.

Mandarin is heard more on the streets of Hong Kong now, in part because over 14.5 million Chinese tourists visit each year.

Analysts say “three flows from China” are now driving Hong Kong’s economy – goods, visitors and capital. In 2010 the move back to Hong Kong from London of HSBC’s CEO was seen as highly symbolic of the shift in the world’s economic centre of gravity to China.

A generation that cannot remember Hong Kong as anything but part of China is coming of age, as a growing sense of civic identity is expressed through issues such as heritage conservation and the preservation of street markets. There is also increased concern about the environment, in particular what can be done to reduce pollution in a city whose haze obscures its iconic views all too often, and where roadside pollution reaches dangerously high levels.

The new generation are also sufficiently confident, and savvy in their use of the internet and social media, to co-ordinate large-scale political protests. The July 1 marches are seen as an established annual event. Only the targets change.